Abstract

The electrochemical conversion of CO2 to methane provides a means to store intermittent renewable electricity in the form of a carbon-neutral hydrocarbon fuel that benefits from an established global distribution network. The stability and selectivity of reported approaches reside below technoeconomic-related requirements. Membrane electrode assembly-based reactors offer a known path to stability; however, highly alkaline conditions on the cathode favour C-C coupling and multi-carbon products. In computational studies herein, we find that copper in a low coordination number favours methane even under highly alkaline conditions. Experimentally, we develop a carbon nanoparticle moderator strategy that confines a copper-complex catalyst when employed in a membrane electrode assembly. In-situ XAS measurements confirm that increased carbon nanoparticle loadings can reduce the metallic copper coordination number. At a copper coordination number of 4.2 we demonstrate a CO2-to-methane selectivity of 62%, a methane partial current density of 136 mA cm−2, and > 110 hours of stable operation.

Subject terms: Energy, Carbon capture and storage, Renewable energy

Electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to methane can store intermittent renewable electricity in a staple of global energy. Here, the authors develop a moderator strategy to maintain the catalyst in a low coordination state, thereby enabling stable and selective electrochemical methanation.

Introduction

The electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) enables the storage of intermittent renewable electricity while utilising CO2 emissions1–5. Methane (CH4) has the largest heating value of 55.5 MJ kg−1 (ref. 6) among CO2RR products, and is the main component of natural gas, well-known for clean and efficient combustion7,8. Natural gas provides 24% of global energy, and the infrastructure for CH4 storage, transportation and consumption is established worldwide9–11. Thus, the electrochemical conversion of CO2 into CH4 offers a means to close the carbon cycle at a scale relevant to the global carbon challenge (Fig. 1a).

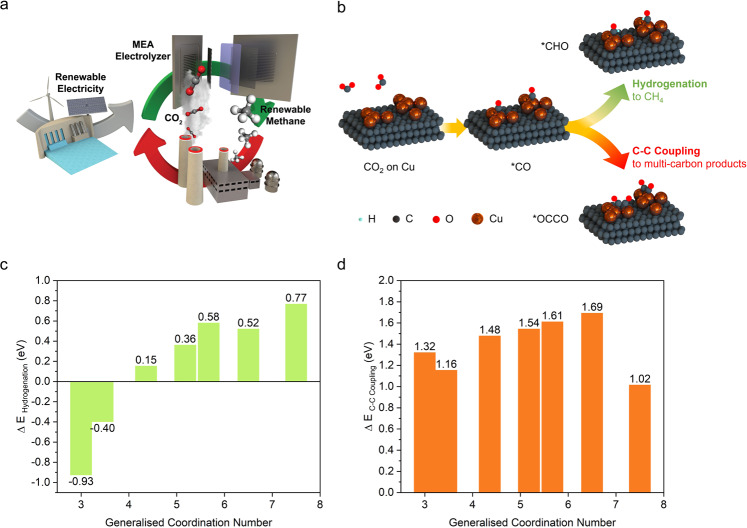

Fig. 1. CO2RR methanation strategy and DFT calculation.

a Schematic of electrochemical carbon recycling in a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) -based electrolyser for CO2-to-CH4. b Schematic of key reaction pathways for CO2RR: hydrogenation to *CHO for CH4 production and C–C coupling to *OCCO leading to C2 generation. c Reaction energies for *CO hydrogenation to *CHO on Cu catalysts of various generalised coordination numbers. d Reaction energies for *CO coupling to *OCCO on Cu catalysts of various generalised coordination numbers.

The application of CO2 electrolysis requires catalysts and systems that operate at current densities over 100 mA cm−2, exhibit high selectivity, and operate for long lifetimes12–17. Prior electrochemical CO2 methanation catalysts have incorporated sputtered copper (Cu) nanoparticles9, Cu-based alloys18, covalent triazine framework Cu (ref. 19) and Cu-complexes20. These approaches have increased CH4 selectivities, albeit at low current densities and short run times. CO2 electrolysers incorporating membrane electrode assemblies (MEA) have recently demonstrated significant advancements in reaction stability, current density and scale-up potential21,22. The anion exchange membrane also provides a highly alkaline environment at the cathode that has been used extensively to promote C–C coupling and multi-carbon product formation on Cu catalysts23–25.

Here we report a low coordination Cu catalyst approach for stable and selective electrochemical CO2 methanation in an MEA. We identify, using density functional theory (DFT) calculations, that the reaction energy for the hydrogenation of the *CO intermediate, essential for CH4 generation, is minimised when lowering the global coordination number of Cu from 7.5 to 3.0. To achieve and maintain low coordination number Cu in an MEA, we design a carbon nanoparticle (CNP) moderator strategy. The CNP isolate and prevent the agglomeration of low coordination number Cu clusters formed during the in situ reduction of a Cu-complex, copper(II) phthalocyanine (CuPc). With a Cu coordination number of 4.2, as verified by in situ extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), we achieve a high CO2RR to CH4 Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 62% with a CH4 partial current density of 136 mA cm−2 and 110 h of stable electrolysis at 190 mA cm−2.

Results and discussion

DFT calculations

We employed a mechanistic CO2RR study to explore the key methanation pathways on Cu catalysts. CO adsorbed on the electrode surface (*CO) is a crucial reaction intermediate toward most C1 and C2 products (Fig. 1b)26,27. The adsorbed *CO intermediate faces two diverging pathways leading to different products. In the first option, the *CO intermediate undergoes electrochemical hydrogenation to *CHO, embarking on the CH4 pathway28. Alternatively, the *CO can couple in a purely chemical manner (no electron transfer is involved) with another *CO to produce *OCCO, subsequently leading to C2 products, such as C2H429. This C–C coupling step is enhanced by the highly alkaline conditions of MEA-based electrolyzers23,24.

We applied DFT calculations to predict the effect of Cu coordination number on hydrogenation and C–C coupling. To accurately represent low values of atomic coordination, adparticles were used to simulate the Cu active sites. Based on these models, we investigated the reaction energies associated with the hydrogenation of the *CO to *CHO (Fig. 1c). The reaction energy for *CO to form *CHO via the hydrogenation step is significantly reduced at low coordination numbers, reaching −0.93 eV at a global coordination number of 3.0, a trend consistent with previous reports30. We then investigated the reaction energies associated with C–C coupling of the *CO intermediate toward *OCCO (Fig. 1d). The reaction energies for *CO to form an *OCCO intermediate via C–C coupling did not change significantly with coordination number. Similarly, the adsorption of H+ to *H (on the pathway to hydrogen evolution) is not significantly influenced by the low coordination states when compared to higher coordination states (Supplementary Fig. 1). These findings indicate that low coordination Cu sites promote *CO hydrogenation, presenting an opportunity to boost the selectivity toward CH4 in MEA-based CO2RR systems.

CO2RR strategy and performance

To obtain these low Cu–Cu coordination sites, we derived our CO2RR catalyst from CuPc. During the reaction, the Cu atoms in the CuPc molecules reduce from Cu(II) to metallic Cu(0) and then agglomerate into clusters20,31. Left uncontrolled, these clusters grew larger than the coordination number predicted by our DFT to be favourable for CH4 production (Fig. 2a). We hypothesised that low coordination number catalysts could be maintained during electrocatalysis with physical confinement within the MEA structure. We designed a CNP moderator strategy to encase and better distribute metallic Cu clusters, thereby resisting Cu agglomeration during the reaction (Fig. 2b).

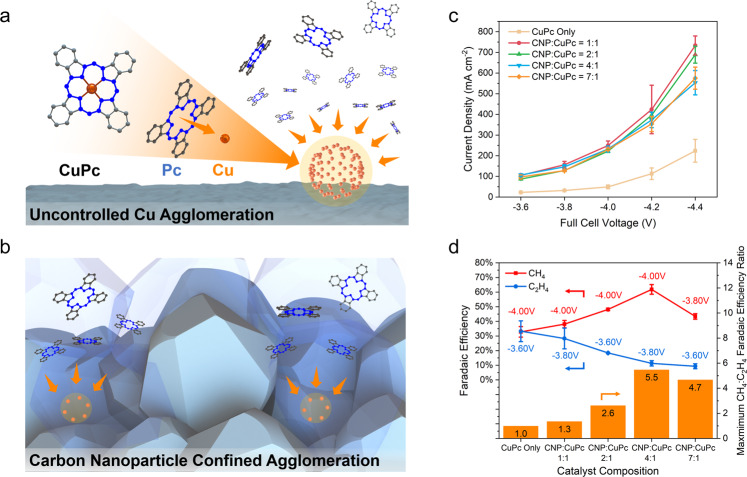

Fig. 2. Effect of the CNP to CuPc ratio on CO2RR methanation performance.

Schematic of the atomic agglomeration (marked with orange arrows) from CuPc reduction a without CNP and b with CNP. c Current-voltage characteristics for samples with different CNP to CuPc ratios. d The maximum FE toward CH4 and C2H4 for samples with different CNP to CuPc ratios when operating between full cell voltages of −3.6 and −4.4 V. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent measurements.

We formulated catalysts from different mass ratios of CNP:CuPc, including CuPc only, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1 and 7:1. These cathode pre-catalysts were then sprayed on a carbon-based gas diffusion electrode (GDE) typical of high activity CO2RR reactors32–34. This spray-based fabrication uses economic precursors and facile preparation, making it compatible with larger electrode fabrication and scaling35. Prepared GDEs were coupled with an anion exchange membrane and iridium oxide-based anode for oxygen evolution in the MEA (Methods, Electrode Preparation & Electrochemical reduction of CO2).

Operating the five different samples at full cell voltages between −3.6 and −4.4 V resulted in an exponential increase of current density with cell voltage (Fig. 2c). The sample made from only CuPc exhibited a lower current density at each voltage than the samples with additional CNP. Compared to layers of the low-conductivity CuPc organic framework36, we posit that the additive CNP improved catalyst utilisation through better electrical contact between neighbouring CuPc molecules. The samples with different CNP ratios exhibited similar current densities at all cell voltages between −3.6 and −4.4 V.

The product distributions obtained during steady-state operation are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2 for all samples. Among the products, CH4 is furthest along the C1 hydrogenation pathway26. With C2H4 being the dominant C2 gas product from CO2RR, its selectivity is an indicator of C–C coupling. The selectivities of CH4 and C2H4 provide an indication of the degree of hydrogenation vs. C–C coupling for comparison with our DFT predictions. To account for the effect of the applied voltage on CO2RR selectivity, we plotted the peak FE values for CH4 and C2H4 within the voltage window of −3.6 to −4.4 V (Fig. 2d). We found that increasing the proportion of CNP in the catalyst composition increased CH4 production. The ratio of 7:1 was the exception to this trend, as all CO2RR product FEs, including CH4 and C2H4, decreased while the hydrogen evolution increased (Supplementary Fig. 2b). As the CNP active sites increased relative to that of the Cu, more H2 production is expected because CNP active sites cannot perform CO2RR and instead produce H2 (Supplementary Fig. 2). A lower density of Cu sites thus lowers CO2RR activity. This suggested a trade-off between methanation and reduced CO2RR activity as the ratio of CNP to CuPc was increased. The highest FE toward CH4, 62%, was exhibited by the 4:1 sample at −4.00 V and 220 mA cm−2 (liquid product analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. 3). Of the five samples, this 4:1 sample also demonstrated the highest peak CH4 to C2H4 FE ratio of 5.5, highlighting the ability of low coordination Cu states to encourage hydrogenation.

In situ mechanistic investigations

To examine the effect of CNP on the Cu coordination number, we investigated the chemical structure at 200 mA cm−2, the current density that corresponds to the maxima of CH4 selectivity for the samples studied, with in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Three representative samples were analysed using this approach: CuPc only, 1:1, and 4:1 ratios of CNP to CuPc, respectively (see Supplementary Note 1).

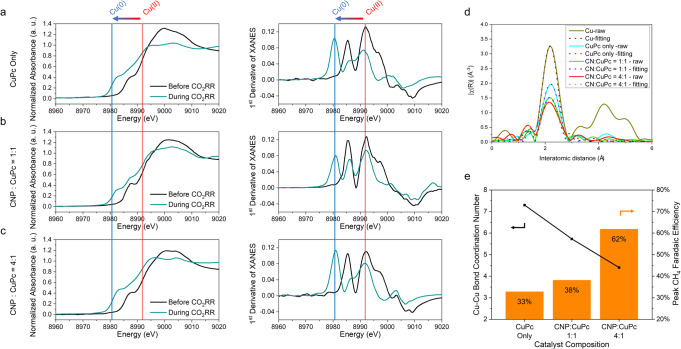

We carried out in situ Cu K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra to probe the oxidation state of Cu in our CuPc complex. To investigate the structural stability of the lower coordination Cu states, we ran the 1:1 and 4:1 samples for longer times. The first derivatives of the corresponding normalised XANES spectra were also computed to ascertain the spectral absorption peaks (Fig. 3a–c, Supplementary Fig. 5). Before CO2RR, the three groups of samples all presented a characteristic Cu(II) peak at ~8991 eV (ref. 37), as expected for the CuPc molecule. When a current density of 200 mA cm−2 was applied in CO2RR working conditions, the major characteristic peak shifted from the initial Cu(II) peak to the Cu(0) peak located at ~ 8980 eV (ref. 38). This shift confirmed that most of the Cu within the CuPc catalyst was indeed reduced to metallic Cu(0) during CO2RR, for all sample compositions (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 3. In situ sample characterisation under electrocatalytic reaction conditions.

Cu K-edge XANES spectra and first-order derivatives of the XANES spectra (collected at 200 mA cm−2 under CO2RR conditions) for the sample containing a only CuPc b a 1:1 ratio of CNP to CuPc c a 4:1 ratio of CNP to CuPc. d Fourier-transformed Cu K-edge EXAFS spectra (collected at 200 mA cm−2 under CO2RR conditions) and fitting lines for samples containing different ratios of CNP to CuPc. e Comparison of the metallic Cu–Cu coordination number determined from EXAFS analysis and methanation selectivity.

To investigate the local structure of Cu, we obtained in situ EXAFS spectra under CO2RR conditions (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 7). The EXAFS spectra of the 4:1 ratio sample stabilised within 50 min of operation with little change between the spectra at 50 and 80 min, demonstrating that the structure was stable once agglomerated (Supplementary Fig. 7d). The fitted metallic Cu–Cu bond scattering path spectra in Fig. 3d were plotted based on fitting parameters shown in Supplementary Table 2.

The metallic Cu–Cu bond coordination number was determined from the fitted scattering paths of the three groups of samples (Fig. 3e). A higher proportion of CNP led to a lower metallic Cu–Cu bond coordination number, confirming the ability of the CNP to limit Cu agglomeration. Combining EXAFS data with CO2RR experimental data indicates that the CO2RR selectivity toward CH4 increased with a decrease of coordination number (Fig. 3e). The highest CH4 FE sample, a 4:1 ratio of CNP vs. CuPc molecules, was found to have a metallic Cu–Cu bond coordination number of ~4.2–much lower than 12, the coordination number of Cu foil (Supplementary Fig. 8). Potentiostatic XAS measurements suggested that CuPc agglomeration was not influenced significantly by the applied potential when the CNP moderator strategy was employed (Supplementary Fig. 9). These results confirm experimentally the DFT prediction that Cu catalysts with low atomic coordination numbers can boost CO2RR methanation.

Ex situ mechanistic investigations

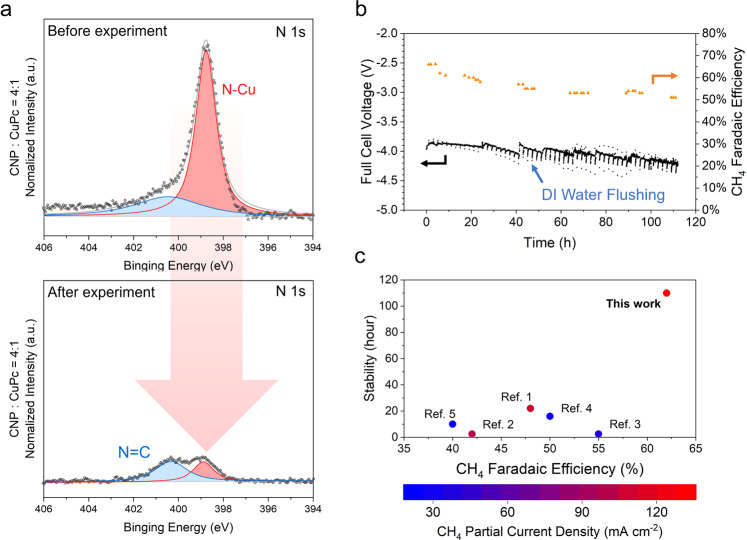

To further investigate the catalytic mechanism, we examined the chemical structure ex situ using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The highest CH4 selectivity performance sample (4:1 ratio of CNP to CuPc) was analysed and compared to its pre-electrolysis state. Since XPS is an ex situ measurement, we expected some oxidation of the Cu sample during the sample disassembly, preparation, and transport. The deconvolved N 1s peaks demonstrate the N–Cu bond in the CuPc molecular structure was decomposed irrevocably39 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 3). The deconvolved Cu 2p peaks show that the CuPc molecules were reduced to the metallic Cu (0) state39,40, and most do not revert back to CuPc after the electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 11). The post-electrolysis X-ray diffraction (XRD) results of the samples demonstrated a decrease in the CuPc characteristic diffraction patterns, compared to the pre-electrolysis states, further confirming CuPc decomposition (Supplementary Fig. 12). These XPS and XRD findings support the conclusion of the in situ XAS measurements, namely that metallic Cu is derived during CO2RR and does not revert to CuPc.

Fig. 4. Ex situ sample characterisation, stability, and performance comparison.

a Pre-electrolysis and post-electrolysis N 1 s XPS spectra for a sample containing a 4:1 ratio of CNP to CuPc. b Prolonged CO2 electroreduction to CH4 for a sample containing a 4:1 ratio of CNP to CuPc at a fixed current density of 190 mA cm−2. c Comparison with the previous CO2RR to CH4 product data reports at high current density. The references are from ref. 9; ref. 52; ref. 53; ref. 54 and ref. 55.

Scanning electron microscopy with secondary electrons (SEM) and backscattered electrons (BS), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were employed to investigate the morphological changes of the pre- and post-electrolysis catalyst samples. The visual absence of large particle formations in the SEM and BS images of the pre- and post-electrolysis samples suggest no large metallic Cu agglomerates were formed during electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 13). Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping and spectroscopy results proved the Cu element is evenly distributed on the GDE (Supplementary Figs. 14, 16 and Supplementary Table 4). STEM/EDX and TEM images taken pre- and post-electrolysis also support the claim that Cu nanoclusters (~2–5 nm) were formed during the reaction (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17).

Stability and performance comparison

To investigate the electrochemical stability of our low coordination Cu catalyst, we performed extended electrolysis galvanostatically at a current density of 190 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4b). To prevent salt accumulation in the gas diffusion layer (GDL) micropores and maintain CO2 mass transport through the GDL, every 2 h we briefly injected DI water into the cathode flow channel (see current fluctuations on Fig. 4b). Every ~24 h additional anode electrolyte, 0.05 M KHCO3, was provided to maintain the original electrolyte volume. The low concentration of electrolyte was chosen to minimise potassium cation crossover and subsequent salt formation41,42. Over the course of the experiment, an average CH4 selectivity of 56% was achieved, and the non-iR compensated full cell voltage exhibited only a minor change, from −3.9 to −4.2 V. In contrast, applying this strategy in a flow cell configuration with liquid catholyte provided only 2 h of continuous operation prior to flooding (Supplementary Fig. 18), a failure mode typical of these systems22,43.

We showcase the performance achieved in this work in the context of three metrics essential for industrial implementation of CO2RR: current density, product selectivity, and stability (Fig. 4c). Compared to the highest current density CH4-focused literature, this work outperformed other catalysts in CH4 selectivity and stability. None of the literature reports in Fig. 4c are from MEA-based electrolysers because this work marks the first MEA system capable of selective (e.g., >50%) CH4 production from CO2 (refs. 21,44,45). The highest FE towards CH4 reported to-date in an MEA is 32%, less than half of the peak methane FE reported in this work45.

In summary, we studied the critical mechanism pathways for CO2RR methanation and multi-carbon production on Cu catalysts. We found low coordination numbers to be beneficial for reducing the hydrogenation energy requirement toward CH4, counteracting the traditionally low energy requirements for C–C coupling found in MEA systems due to the high basic alkaline conditions found on the cathode. Guided by this finding, we designed a low coordination Cu catalyst, synthesised with CNP additives, which encase and better distribute Cu clusters to prevent excessive agglomeration, for use in an MEA system. This catalyst-system combination converted CO2 to CH4 at a FE of 62% and a partial current density of 136 mA cm−2. The same catalyst operated for 110 h at a current density of 190 mA cm−2 with an average FE of 56%. The stability of this strategy is a significant advance toward electrochemically derived renewable methane.

Methods

DFT calculations

We performed DFT calculations with the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) code46,47. The exchange correlation energy was modelled by using Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the generalised gradient approximation (GGA)48. The projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudo-potentials49 were used to describe ionic cores. The cutoff energy of 500 eV was adopted after a series of tests. A Methfessel-Paxton smearing of 0.05 eV to the orbital occupation is applied during the geometry optimisation and for the total energy computations. In all calculations, the atoms at all positions have Hellmann–Feynman forces lower than 0.02 eV Å−1 and the electronic iterations convergence was 10−5 eV using the Normal algorithm. A 4-layer (4 × 4) Cu (111) supercell was built to simulate the exposed surface of Cu while ensuring a vacuum gap of 15 Å. The Cu active sites with various coordination numbers were constructed via creating Cu vacancies on the surface or subsurface. We first ran the stability test for these defective surface models to choose the most stable Cu configurations (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Note 2). Structural optimisations were performed on all slab models with a grid of (3 × 3 × 1) k-point. During the adsorption calculations, the top three layers are fully relaxed while the other layers are fixed at the tested lattice positions. All reaction energy calculations were described in Supplementary Note 3.

Electrode preparation

The cathode GDE were prepared by airbrushing catalyst inks with a carrier gas of nitrogen. The catalyst ink was prepared with 30 mL ethanol (Greenfield Global Inc., >99.8%), 150 μL Nafion (Fuel Cell Store D521 Alcohol based 1100 EW, 5 wt%) and catalytic material. The catalytic material quantities varied by sample. For example, the sample containing only CuPc was made with 14 mg of CuPc (Sigma–Aldrich 546682, >99%). Similarly, The catalytic materials for CNP:CuPc ratios of 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, 7:1 and CNP only were made with 14 mg CNP (Alfa Aesar 39724, 75 m2 g−1) + 14 mg of CuPc, 14 mg CNP + 7 mg CuPc, 14 mg CNP + 3.5 mg CuPc, 14 mg CNP + 2 mg CuPc and 14 mg CNP + no CuPc, respectively. The catalyst ink mixtures were sonicated for 5 h, and then sprayed on a gas diffusion carbon paper (Fuel Cell Store Sigracet 39 BC, with microporous layer) with a spray density of 0.22 mL cm−2. After airbrushing, the GDE was dried for 24 h at room temperature (~20 °C). The anode electrode was prepared by dip-coating iridium chloride (Alfa Aesar, IrCl3·xH2O 99.8%) on titanium support (0.002” thickness, Fuel Cell Store). Then, IrOx was formed on the coated electrode by thermal decomposition in air50.

Characterisation

Catalyst surface morphology was imaged by a Hitachi S-5200 SEM at 10 kV and JEOL JEM-2010 HRTEM at 200 kV. Elemental analysis was investigated with field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-6700F) equipped energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Oxford Instrument XMax 150 mm2). The lattice fringes and elemental mapping were collected with field-emission transmission electron microscopy (FE-TEM, JEOL-2100F) equipped energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Oxford Instrument XMaxN TSR). In situ hard XAS measurements were conducted using a modified flow cell at beamline 9BM of the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Argonne National Laboratory, Lemont, Illinois, United States)51 and the silicon drift detector at the 44 A beamline of National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC, Hsinchu, Taiwan). XRD measurements were performed on a Rigaku MiniFlex600 G6. XPS measurements were conducted using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrophotometer with a monochromated Al Kα X-ray radiation source.

Electrochemical reduction of CO2

All CO2RR experiments were performed using an MEA electrolyser with an active area of 5 cm2 (Supplementary Fig. 19). During a CO2RR experiment, the aqueous 0.05 M KHCO3 anolyte was circulated through the anode flow channel at a flow rate of 25 mL min−1 using a peristaltic pump. An anion exchange membrane (Sustainion X37–50, Dioxide Materials) was used as the solid cathode electrolyte. The CO2 gas flow rate, supplied at a rate of 80 standard cubic centimetres per minute (sccm), was bubbled through water for humidification prior to entering the electrolyser. All voltages reported are full cell voltages without iR compensation.

The CO2RR gas products were analysed in 1 mL volumes using a gas chromatograph (PerkinElmer Clarus 590) possessing a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a flame ionisation detector (FID). The liquid products were quantified using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). 1H NMR spectra of freshly acquired samples were collected on an Agilent DD2 500 spectrometer with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as an internal standard. For the screening of samples with different CuPc:CNP ratios, gas and liquid samples were taken after two hours of CO2RR to ensure that the system was at steady state. Faradaic efficiency (FE) of CO2RR gas product was calculated by the following equation:

| 1 |

where is the volume fraction of gas product i, is the outlet gas flow rate in sccm, zi is the number of electrons required to produce one molecule of product i, is the Faraday Constant, is atmosphere pressure, is the ideal gas constant, is the temperature, and is the total current.

The FE of CO2RR liquid product was calculated by the following equation:

| 2 |

where is the number of moles of liquid product i, and is the cumulative charge as the liquid products were collected.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. Support from Canada Research Chairs Program is gratefully acknowledged, as is support from an NSERC E.W.R. Steacie Fellowship to D.S. Y.X. acknowledges NSERC for their support through graduate scholarships. J.P.E. thanks NSERC, Hatch, and the Government of Ontario for their support through graduate scholarships. We acknowledge Centre for Nanostructure Imaging at the University of Toronto and Dr. Ilya Gourevich for sample SEM and TEM characterisation. Thanks to Ms. C.-Y. Chien of the Ministry of Science and Technology (National Taiwan University) for the assistance in FE-TEM and EDS experiments. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory and was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357, and the Canadian Light Source and its funding partners. We thank Dr. Tianpin Wu and Dr. George Sterbinsky from 9BM beamline for assistance in collecting the XAS data at the advanced photon source (APS).

Author contributions

D.S. and E.H.S. supervised the project. Y.X. designed and carried out all the experiments. F.L. designed and analysed the sample characterisation. A.X. carried out the DFT simulation. Y.X., F.L. and J.P.E. analysed the experimental data and prepared the manuscript. C.M.G., C.P.O., S.L. and R.K.M. designed and performed the stability test. S.F.H., F.L., X.W. and J.A. performed and analysed the in situ and ex situ XAS measurements. J.W. performed the XPS measurements. Y.Liu. performed XRD measurements and data analysis. Y.Li., J.L., J.E.H. and Y.W. contributed to data analysis and manuscript polishing. All authors discussed the results and assisted during manuscript preparation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yi Xu, Fengwang Li.

Contributor Information

Edward H. Sargent, Email: ted.sargent@utoronto.ca

David Sinton, Email: sinton@mie.utoronto.ca.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-23065-4.

References

- 1.Kibria MG, et al. Electrochemical CO 2 reduction into chemical feedstocks: from mechanistic electrocatalysis models to system design. Adv. Mater. 2019;31:1807166. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birdja YY, et al. Advances and challenges in understanding the electrocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to fuels. Nat. Energy. 2019;4:732–745. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0450-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreier M, et al. Solar conversion of co2 to CO using earth-abundant electrocatalysts prepared by atomic layer modification of CuO. Nat. Energy. 2017;2:1–9. doi: 10.1038/nenergy.2017.87. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang Y, et al. Efficient electrocatalytic conversion of carbon monoxide to propanol using fragmented copper. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:251–258. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0225-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morales-Guio CG, et al. Improved CO2 reduction activity towards C2+ alcohols on a tandem gold on copper electrocatalyst. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:764–771. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0139-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babu, V. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics. Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics (CRC Press, 2019).

- 7.Haynes CA, Gonzalez R. Rethinking biological activation of methane and conversion to liquid fuels. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wigley TML. Coal to gas: the influence of methane leakage. Clim. Change. 2011;108:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0217-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, et al. Efficient methane electrosynthesis enabled by tuning local CO2 availability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:3525–3531. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b12445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, et al. Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy. Science. 2020;368:297–303. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz8881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BPSTATS. BP statistical review of World Energy Statistical Review of World, 68th edition. B. P. Stat. Rev. World Energy https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2019-full-report.pdf (2019).

- 12.Jouny M, Luc W, Jiao F. General techno-economic analysis of CO2 electrolysis systems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018;57:2165–2177. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b03514. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma, S., Kim, B., Jhong, H.-R., Molly, Ma, S. & Kenis, P. J. A. A Gross-margin model for defining technoeconomic benchmarks in the electroreduction of CO2. ChemSusChem9, 1972–1979 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Verma S, Lu S, Kenis PJA. Co-electrolysis of CO2 and glycerol as a pathway to carbon chemicals with improved technoeconomics due to low electricity consumption. Nat. Energy. 2019;4:466–474. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0374-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arán-Ais RM, Scholten F, Kunze S, Rizo R, Roldan Cuenya B. The role of in situ generated morphological motifs and Cu(i) species in C2+ product selectivity during CO2 pulsed electroreduction. Nat. Energy. 2020;5:317–325. doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-0594-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parastaev A, et al. Boosting CO2 hydrogenation via size-dependent metal–support interactions in cobalt/ceria-based catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2020;3:526–533. doi: 10.1038/s41929-020-0459-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Z, et al. Selectivity control of CO versus HCOO− production in the visible-light-driven catalytic reduction of CO2 with two cooperative metal sites. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:801–808. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0331-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhl KP, et al. Electrocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to methane and methanol on transition metal surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14107–14113. doi: 10.1021/ja505791r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma L, et al. Covalent triazine framework confined copper catalysts for selective electrochemical CO2 reduction: operando diagnosis of active sites. ACS Catal. 2020;10:4534–4542. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c00243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng Z, et al. Active sites of copper-complex catalytic materials for electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:415. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02819-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabardo CM, et al. Continuous carbon dioxide electroreduction to concentrated multi-carbon products using a membrane electrode assembly. Joule. 2019;3:2777–2791. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2019.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nwabara UO, Cofell ER, Verma S, Negro E, Kenis PJA. Durable cathodes and electrolyzers for the efficient aqueous electrochemical reduction of CO 2. ChemSusChem. 2020;13:855–875. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201902933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng L-C, Bell AT, Weber AZ. Towards membrane-electrode assembly systems for CO 2 reduction: a modeling study. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:1950–1968. doi: 10.1039/C9EE00909D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinh C-T, et al. CO 2 electroreduction to ethylene via hydroxide-mediated copper catalysis at an abrupt interface. Science. 2018;360:783–787. doi: 10.1126/science.aas9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma W, et al. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethylene and ethanol through hydrogen-assisted C–C coupling over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Catal. 2020;3:478–487. doi: 10.1038/s41929-020-0450-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitopi S, et al. Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:7610–7672. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todorova TK, Schreiber MW, Fontecave M. Mechanistic understanding of CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) toward multicarbon products by heterogeneous copper-based catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020;10:1754–1768. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b04746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson AA, Abild-Pedersen F, Studt F, Rossmeisl J, Nørskov JK. How copper catalyses the electroreduction of carbon dioxide into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010;3:1311–1315. doi: 10.1039/c0ee00071j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montoya JH, Shi C, Chan K, Nørskov JK. Theoretical insights into a CO dimerisation mechanism in CO2 electroreduction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2032–2037. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Z, Chen Z, Zhang X, Lu G. Generalized surface coordination number as an activity descriptor for CO2 reduction on Cu surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:28125–28130. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b10155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karapinar D, et al. Carbon‐nanotube‐supported copper polyphthalocyanine for efficient and selective electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to CO. ChemSusChem. 2020;13:173–179. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201902859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdyny T, Smith WA. CO2 reduction on gas-diffusion electrodes and why catalytic performance must be assessed at commercially-relevant conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:1442–1453. doi: 10.1039/C8EE03134G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, et al. Oxygen-tolerant electroproduction of C 2 products from simulated flue gas. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:554–561. doi: 10.1039/C9EE03077H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weng L-C, Bell AT, Weber AZ. Modeling gas-diffusion electrodes for CO 2 reduction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:16973–16984. doi: 10.1039/C8CP01319E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng T, et al. Large-Scale and Highly Selective CO2 Electrocatalytic Reduction on Nickel Single-Atom Catalyst. Joule. 2019;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Nahass MM, Bahabri FS, Al Ghamdi AA, Al-Harbi SR. Structural and transport properties of copper phthalocyanine (CuPc) Thin Films. Egypt. J. Sol. 2002;25:307–321. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank P, Benfatto M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO. The X-ray absorption spectroscopic model of the copper(II) Imidazole complex ion in liquid aqueous solution: a strongly solvated square pyramid. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:2086–2096. doi: 10.1021/ic2017819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaur A, Shrivastava BD, Joshi SK. Copper K-edge XANES of Cu(I) and Cu(II) oxide mixtures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009;190:012084. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/190/1/012084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Oteyza DG, et al. Copper-phthalocyanine based metal–organic interfaces: the effect of fluorination, the substrate, and its symmetry. J. Chem. Phys. 2010;133:214703. doi: 10.1063/1.3509394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumari P, Majewski P. Adsorption of albumin on silica surfaces modified by silver and copper nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2013;2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/839016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y, et al. Self-cleaning CO2 reduction systems: unsteady electrochemical forcing enables stability. ACS Energy Lett. 2021;6:809–815. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Endrödi B, et al. Multilayer electrolyzer stack converts carbon dioxide to gas products at high pressure with high efficiency. ACS Energy Lett. 2019;4:1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.9b01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leonard ME, Clarke LE, Forner‐Cuenca A, Brown SM, Brushett FR. Investigating electrode flooding in a flowing electrolyte, gas‐fed carbon dioxide electrolyzer. ChemSusChem. 2020;13:400–411. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201902547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren S, et al. Molecular electrocatalysts can mediate fast, selective CO 2 reduction in a flow cell. Science. 2019;365:367–369. doi: 10.1126/science.aax4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aeshala LM, Uppaluri RG, Verma A. Effect of cationic and anionic solid polymer electrolyte on direct electrochemical reduction of gaseous CO2 to fuel. J. CO2 Util. 2013;3–4:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2013.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kresse G, Hafner J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 1993;47:558–561. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 1996;6:15–50. doi: 10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Payne MC, Teter MP, Allan DC, Arias TA, Joannopoulos JD. Iterative minimisation techniques for ab initio total-energy calculations: molecular dynamics and conjugate gradients. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1992;64:1045–1097. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.64.1045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luc W, Rosen J, Jiao F. An Ir-based anode for a practical CO2 electrolyser. Catal. Today. 2017;288:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2016.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li J, et al. Copper adparticle enabled selective electrosynthesis of n-propanol. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4614. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang T, et al. Highly dispersed, single-site copper catalysts for the electroreduction of CO2 to methane. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020;875:113862. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.113862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, et al. Single-atomic Cu with multiple oxygen vacancies on ceria for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to CH4. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7113–7119. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weng Z, et al. Self-cleaning catalyst electrodes for stabilized CO2 reduction to hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:13135–13139. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guan A, et al. Boosting CO2 electroreduction to CH4 via tuning neighboring single-copper sites. ACS Energy Lett. 2020;5:1044–1053. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.0c00018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.