Abstract

Clinical trials indicate that sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) improve kidney function, yet, the molecular regulation of SGLT2 expression is incompletely understood. Here, we investigated the role of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) on SGLT2 expression. In adult non-diabetic participants in the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE, N=163), multivariable linear regression analysis showed SGLT2 mRNA was significantly associated with angiotensinogen (AGT), renin, and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) mRNA levels (p<0.001). In vitro, angiotensin II (Ang II) dose-dependently stimulated SGLT2 expression in HK-2, human immortalized renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs); losartan and antioxidants inhibited it. Sglt2 expression was increased in transgenic mice specifically overexpressing Agt in their RPTCs, as well as in WT mice with a single subcutaneous injection of Ang II (1.44 mg/kg). Moreover, Ang II (1000 ng/kg/min) infusion via osmotic mini-pump in WT mice for 4 weeks increased systolic blood pressure (SBP), glomerulosclerosis, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and albuminuria; canaglifozin (Cana, 15 mg/kg/day) reversed these changes, with the exception of SBP. Fractional glucose excretion was higher in Ang II+Cana than WT+Cana, whereas Sglt2 expression was similar. Our data demonstrate a link between intrarenal RAS and SGLT2 expression and that SGLT2i ameliorates Ang II-induced renal injury independent of SBP.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Hypertension, Intrarenal RAS, SGLT 2 Regulation, Tubulointerstitial fibrosis, Transgenic mice

Introduction

Recent large clinical trials have reported that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have renoprotective effects in a glucose-independent manner in patients with type 2 diabetes [1–3]. Despite the compelling evidence, the mechanisms underlying renoprotection are incompletely understood. One proposed mechanism is that SGLT2i exerts renal hemodynamic effects by reducing the intraglomerular pressure via the activation of tubulo-glomerular feedback [4, 5]. Other studies have suggested that SGLT2i may decrease the inflammatory and fibrotic responses to hyperglycemia in renal proximal tubular cells (RPTCs) [6, 7] and mesangial cells [8]. Based on such findings, SGLT2i has been proposed as a potential renoprotective agent for patients with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease (CKD) [9]. Indeed, results from recent clinical trials have indicated that SGLT2i exerts a positive effect in non-diabetic CKD [10, 11].

In order to assess the efficacy of SGLT2i in various CKD, it is important to consider the endogenous expression level of SGLT2. While some studies reported increased SGLT2 expression in type 1 and 2 diabetes in murine experimental models [12] and humans [13], others found decreased SGLT2 mRNA expression in kidney biopsies of patients with diabetes compared to healthy controls or patients with non-diabetic glomerular diseases in a cohort of patients with samples in the European Renal cDNA Bank [14]. There is only limited information available on SGLT2 expression in non-diabetic CKD. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the clinical efficiency of SGLT2i corresponds to endogenous SGLT2 expression levels.

We previously showed unchanged expression of renal angiotensinogen (Agt, the sole precursor of all angiotensins) in non-diabetic [15] or diabetic [16] mice treated with SGLT2i. Here, we investigated the impact of increased renal Agt and its down-stream angiotensin II (Ang II) on SGLT2 expression. Moreover, we also asked whether altered SGLT2 expression by Ang II could affect the efficacy of renoprotective action of SGLT2i in Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury, a well-established model of human hypertension-associated nephrosclerosis.

Methods

Chemical and reagents

Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Cat. No. 11966–025), Ham’s F12 medium (Cat. No. 11765–054) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Montreal, QC, Canada). Catalase (Cat), apocynin (APO), diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI), fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled inulin and Ang II were bought from Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd. (Oakville, ON, Canada). 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxy- D-glucose (2-NBDG) (Cat. No. N13195) was purchase from Invitrogen, Inc. (Burlington, ON, Canada). HK-2 cell line (Cat. No. CRL-2190) was obtained from American Tissue Cell Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA) (http://www.atcc.org). Canagliflozin (Invokana) was purchased from Janssen Inc. (Toronto, ON, Canada). Losartan was obtained from DuPont Merck (Wilmington, DE).

Cell culture

HK-2 cells, a human proximal tubular cell line, were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham’s F12 medium containing 10% of FBS. Cells were synchronized overnight in serum-free 5 mmol/L glucose DMEM at 80–90% confluence and were cultured in 5 mmol/L glucose DMEM containing 1% depleted FBS in the absence or presence of Ang II (10−13to 10−5 mol/L). A separate set of HK-2 cells were preincubated with losartan (10−6 mol/L) for 1 hour before adding Ang II (10−7 mol/L). After 24 hours of incubation, cells were harvested, and RNA was isolated for subsequent analysis of SGLT2 mRNA quantification by real-time qPCR. Another set of HK-2 cells were similarly incubated with Ang II (10−7 mol/L), with and without losartan (10−6 mol/L), for 24 hours, and immunostaining for SGLT2 was performed (SGLT2 antibody is listed in Supplementary Table 1). Semi-quantification of SGLT2 positive cells was calculated as a ratio of SGLT2-immunopositive cells /total counted cells. At least 20 cells were evaluated for each calculation. The plasmid pGL4.20 hSGLT2 promoter (N-1986/N+17?) [15] and control plasmid pGL4.20 were stably transfected to HK-2 cells. Promoter activity was measured by the luciferase activity assay. Cells were treated with Ang II in the absence or presence of one of the following antioxidants: Cat, APO or DPI [17]. Cellular glucose uptake was assessed as 2-NBDG entry into the cells as previously described [18]. In brief, HK2 cells were plated at 1 × 104/well of the 96-well plates, and control cells as well as cells treated with Ang II (10−7 mol/L) with and without losartan (10−6 mol/L) were pre-incubated for 24 hours as descript above. Cells were incubated in glucose free sodium buffer (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)) containing 100 μM 2-NBDG. After 60 min incubation, 2-NBDG buffer was removed and cells was washed with PBS three times. The 2-NBDG fluorescence intensity was detected by BioTek fluorescence microplate reader with the filter of excitation: 488-nm and emission:545-nm.

Agt-Tg mice and Agt/Cat-Tg mice

Transgenic (Tg) mice (C57BL/6 background), specifically overexpressing rat Agt in RPTCs were generated in our laboratory (Agt-Tg, J.S.D Chan) by employing the kidney-specific, androgen-regulated protein (KAP) gene promoter linked to rat Agt cDNA [19]. Cat-Tg mice (C57BL/6 background), specifically overexpressing rat catalase in RPTCs were similarly generated in our laboratory (J.S.D Chan) [20]. Agt/Cat-Tg mice were created by cross-breeding the Agt-Tgs and Cat-Tgs [21]. Male Agt-Tg mice were treated with or without renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blocker (losartan 30 mg/kg/day, in the drinking water) from week 13 until week 20 [22]. At 20 weeks of age, mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and the kidneys were removed and processed for histology. Non-transgenic littermates (WT) served as controls.

Single-dose bolus Ang II injection study

We used male WT mice at age 16 weeks (C57BL/6 background, N=18, Figure 4A). Control group (N=6) received a normal (0.9%) saline and Ang II group (N=6) received Ang II (1.44 mg/kg) subcutaneously. LOS+Ang II group (N=6) received losartan in drinking water (15 mg/kg/day) for 7 days before Ang II injection. Eighteen hours after the injection of either Ang II or saline, mice were euthanized with intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital. The kidneys were removed, decapsulated, and weighed. Kidneys were harvested for histology and RPT isolation by Percoll gradient [15, 19]. To ensure losartan did not cause hypotension in WT mice, systolic blood pressure (SBP) was monitored using BP-2000 tail-cuff (Visitech Systems, Apex, NC) [15, 16]. Mice were acclimated to SBP measurements daily for a week before the study, and the pre-Ang II-infusion SBP was measured on 3 consecutive days before Ang II injection.

Figure 4: Effect of single-dose bolus injection of Ang II.

(A) Schematic design of the study protocol. SBP, systolic blood pressure. Ang II, angiotensin II. (B) Sglt2 and Agt mRNA, (C) Double immunostaining of Sglt2 (red color, arrow) and a proximal tubular marker (lotus tetragonolobuslectin, LTL) (green color) in Ctrl (Saline), Ang II, and Los+Ang II mice (x200). Scale bars = 50 μm. G, glomerulus. (D) Semi-quantification of Sglt2/LTL ratio in Ctrl, Ang II and Los+Ang II mice. Values are means ± SEM, n = 6/group. ***p < 0.001. Los, losartan. NS, not significant.

Chronic Ang II infusion study

Male WT mice at the age of 16 weeks (C57BL/6 background, N=32, Figure 5A) were implanted Alzet osmotic minipumps (Durect Corporation, CA) subcutaneously in the dorsum of the neck under isoflurane anesthesia to maintain a delivery rate of 1000 ng/kg/min of Ang II for 4 weeks (N=16) [23]. Some mice (Ang II-Cana, N=8) received canagliflozin in the drinking water (15 mg/kg/day) [24] starting from the second week. Mice without Ang II infusion received a sham surgery, and were divided into 2 groups; Ctrl (N=8) with regular water and Ctrl-Cana (N=8) with canagliflozin (15 mg/kg/day) for the same duration.

Figure 5: Physiological parameters of mice following 4 weeks of high-dose Ang II infusion with and without canagliflozin.

(A) Schematic design of the study protocol. Wk, week. (B) Longitudinal measurements of average SBP measurements (performed 2–3 times per mouse per week in the morning), * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 for Ang II vs Ctrl and Ang II-Cana vs Ctrl-Cana. (C) BW (body weight) change profile and (D) urinary glucose concentration by glucose colorimetric kit. Values are means ± SEM, n = 8 for each group. *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01. (E) Blood glucose, (F) fractional glucose excretion (FeGlu), (G) Glomerular filtration rate (GFR)/BW ratio, and (H) 24-hour urinary albumin excretion at week 4 (n=6–8/group). *p<0.05. **p< 0.01. ***p<0.001. NS, not significant.

Physiological measurements in chronic Ang II infusion study

The mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room regulated on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and had free access to standard mouse chow and water. The concentration of canagliflozin was adjusted at least 3 times a week based on the amount of water intake. Two weeks before the pump implantation surgery, mice were acclimated to SBP measurements daily for a week. Starting from 1 week before to 4 weeks after surgery, SBP was measured at least 3 times per week. BW was measured weekly. Non-fasting BG was measured weekly by Accu-Chek Performa (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, QC, Canada).

Twenty-four hours before euthanasia, the mice were housed in individual metabolic cages, food intake and water consumption were measured, and urine was collected. The GFR was estimated from fluorescein isothiocyanate inulin plasma clearance in conscious mice as recommended by the Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium (http://www.diacomp.org/) with slight modifications [25, 26]. Immediately after the GFR measurements, mice were euthanized with intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital. The kidneys and hearts were weighed. Kidneys were harvested for histology and RPT isolation by Percoll gradient [15, 19].

Mouse serum and urine biochemical measurements

We measured urinary albumin and glucose concentration using ELISA kit Albuwell (Exocell, Inc., Philadelphia, PA) and colorimetric-enzymatic method Autokit Glucose (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA), respectively. Urine samples were extracted with C18 Sep-Pak columns (Waters, Mississauga, ON) and assayed for Ang II by specific ELISA (Bachem America, Torrence, CA) according to the number III protocol [15]. Serum sodium, potassium, creatinine and BUN, as well as urine sodium, potassium and creatinine were measured by the Comparative Medicine and Animal Resources Centre, McGill University (Montreal, QC, Canada) (N=6/group). Hematocrit was determined using glass microcapillaries at the first time point of inulin clearance.

Fractional sodium excretion (FeNa) and fractional glucose excretion (FeGlu) were calculated using the 24-hour urine volume, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and serum and urine sodium or glucose concentration [27, 28]. Electrolyte-free water clearance was also calculated using 24-hour urine volume, serum and urine sodium, and urine potassium, as previously described [28].

Renal pathology

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the tissue was processed to paraffin, sectioned at 3 μm, and stained with standard periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Kidney fibrosis was analyzed with Sirius red staining using standard protocols. The sources of antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Semi-quantitation of the relative staining was done for 4–6 mouse kidneys per group by NIH Image J software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). The degree of glomerular damage was assessed on PAS-stained sections in a blinded manner using a semi-quantitative scoring method as previously reported [29–31]: Glomerulosclerotic index =(1 × n1) + (2 × n2) + (3 × n3) + (4 × n4) / (n0 + n1 + n2 + n3 + n4), where nx is the number of glomeruli at each grade of glomerulosclerosis (n0, normal glomeruli; n1, sclerotic area 0 to 25%; n2, 25 to 50%; n3, 50 to 75%; n4, 75 to 100%). At least 60 glomerular sections were randomly examined in each mouse (n = 6/group).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

The mRNA levels of various genes in isolated RPTCs were quantified by real-time quantitative PCR with the forward and reverse primers listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE)

NEPTUNE, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), is a multicenter prospective cohort study enrolling patients with proteinuric glomerular disease and performing comprehensive clinical and molecular phenotyping [32, 33]. Patients with secondary renal disease, such as lupus nephritis and amyloidosis, were excluded. From the NEPTUNE database, we selected adult participants (≥ 18 years old) without known history of diabetes for our analysis. We studied the genome-wide mRNA expression from microdissected tubulointerstitium (TI) compartment of the renal biopsy cores [34]. Data files created by Affymetrix microarrays were normalized by the Robust Multiarray method and annotated with the Human Entrez Genes custom cdf version 10 (http://brainarray.mbni.med.umich.edu). Expression values were log2 transformed and batch corrected [14, 34]. Socio-demographic data, medical history, blood and urine laboratories, renal morphologic data (quantitated interstitial fibrosis level) were available for analysis. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are reported as mean ± standard error if normally distributed and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. For between group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze correlation between continuous variables. In the NEPTUNE database, univariable and then multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to identify the independent determinants of SGLT2 mRNA expression. We confirmed that the presence of multicollinearity was unlikely based on the variance inflation factors (VIFs). Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software packages SAS University Edition (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for NEPTUNE data and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) for animal and in vitro data. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

All animals procedures were approved by the CRCHUM Animal Care Committee (approval# M2R3 CM16016JCs) and performed at CRCHUM in accordance with the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85–23, revised 1985; http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/olaw/references/phspol.htm). NEPTUNE was approved by collaborating center Institutional Review Boards, and subjects or guardians provided written informed consent to participate. The research has been carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

SGLT2 mRNA expression is positively associated with mRNA expressions of RAS components in human kidney biopsies

We analyzed mRNA expression of SGLT2 and RAS components in kidney biopsies from participants of the NEPTUNE cohort. SGLT2 mRNA expression from micro-dissected TI was available from 183 adult participants; 163 non-diabetic patients with proteinuria and 20 control subjects (15 nephrectomies due to cancer and 5 living donors). Baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1 (n=163) with the exception of controls, for which data were not available. There was no difference in SGLT2 expression between the disease groups (Figure 1A). SGLT2 mRNA positively correlated with AGT (r = 0.55, p<0.001), renin (r = 0.46, p<0.001) and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (r = 0.47, p<0.001) mRNA (Figure 1B–D). There was a weak but statistically significant negative correlation between SGLT1 and SGLT2 mRNA levels (r = −0.28, p<0.001; Figure 1E). These variables were analyzed with multivariable linear regression to identify the independent associations with SGLT2 expression (Table 2). In univariable analysis, SGLT2 mRNA positively correlated with eGFR and negatively correlated with interstitial fibrosis (Table 2), which was consistent with a previous report [14]. Multivariable analysis revealed AGT, renin, ACE, and SGLT1 mRNA as independent determinants of the SGLT2 mRNA expression (Table 2). RAS blocker use was not associated with altered SGLT2 expression (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the time of the kidney biopsy (N=163)

| Gender; Male, n (%) | 106 (65) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 101 (62) | |

| African American | 35 (21) | |

| Asian American | 16 (10) | |

| Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1 (1) | |

| Multi-Racial | 5 (3) | |

| Unknown | 5 (3) | |

| Age, yr | 44 ± 1 | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| MCD | 26 (16) | |

| FSGS | 46 (28) | |

| MN | 41 (25) | |

| IgAN | 22 (14) | |

| Other | 28 (17) | |

| Hypertension at baseline, n (%) | 88 (54) | |

| RAS blocker use, n (%) | 102 (63) | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 124 ± 2 | |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 77 ± 1 | |

| Blood Glucose, mg/dL | 92 [83–101] | |

| HbA1c, % | 5.5 ± 0.1 | |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 74 [45–94] | |

| UPCR, g/gCr | 2.3 [0.9–3.8] | |

| Interstitial fibrosis, % | 10 [4–25] | |

Continuous, normally distributed variables are presented as means ± SEM; continuous, non-normally distributed variables are presented as median [IQR]; and categorical variables are presented as number (n) with percentages. RAS, renin-angiotensin system; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UPCR, urine protein/creatinine ratio.

Figure 1: Correlation of RAS genes and SGLT2 mRNA expression in the renal tubules of NEPTUNE participants and healthy controls (N=183).

(A) Comparison of tubular SGLT2 mRNA expression between controls (N=20), minimal change disease (MCD, N=26), focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS, N=46), membranous nephropathy (MN, N=41), IgA nephropathy (IgAN, N=22), and other CKD (N=28). Correlations of tubular SGLT2 mRNA expression and (B) angiotensinogen (AGT), (C) renin, (D) angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), and (E) SGLT1 mRNA levels. r, Pearson correlation coefficient.

Table 2.

Associations of SGLT2 mRNA expression with clinical and laboratory data

| (N=163) | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p value | β | p value | |

| Age, yr | −0.0076 | 0.14 | - | |

| Gender (Male) | −0.1943 | 0.27 | - | |

| RAAS blocker use | −0.0101 | 0.95 | - | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | −0.0049 | 0.24 | - | |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | −0.0041 | 0.53 | - | |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | −0.0018 | 0.70 | - | |

| HbA1c, % | 0.2196 | 0.52 | - | |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 0.0102 | <0.001 | 0.0015 | 0.60 |

| UPCR, g/gCr | −0.0504 | 0.05 | - | |

| Interstitial Fibrosis, % | −0.0141 | 0.005 | −0.0020 | 0.68 |

| log2SGLT1 mRNA | −0.3291 | <0.001 | −0.4044 | <0.0001 |

| log2AGT mRNA | 0.7140 | <0.001 | 0.5707 | <0.0001 |

| log2Renin mRNA | 0.3048 | <0.001 | 0.1482 | <0.001 |

| log2ACE mRNA | 0.5638 | <0.001 | 0.2450 | <0.01 |

RAS, renin-angiotensin system; BP, blood pressure; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; UPCR, urine protein/creatinine ratio.

Variables entered in the model: eGFR, interstitial fibrosis, log2SGLT1 mRNA, log2AGT mRNA, log2Renin mRNA, and log2ACE mRNA.

Ang II up-regulates SGLT2 expression in HK-2 cells

Next, we investigated the impact of Ang II on SGLT2 expression in vitro, using the human immortalized renal proximal tubular cell line (HK-2). Culture of HK-2 cells with Ang II led to induction of SGLT2 mRNA in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A). Incubation of HK-2 cells with losartan (AT1R antagonist) abolished the effects of Ang II (Figure 2A), indicating that Ang II stimulates SGLT2 expression via AT1R. Human SGLT2 promoter activity (Figure 2B) and SGLT2 immunostaining (Figure 2C, D) in response to Ang II with and without losartan confirmed this observation. Furthermore, the stimulatory effect of Ang II on SGLT2 promoter activity was attenuated by catalase (H2O2 decomposer enzyme), apocynin and DPI (inhibitors of NADPH oxidase (NOX)) (Figure 2E), indicating that activation of NADPH oxidase followed by reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation is required for Ang II to stimulate SGLT2.

Figure 2: Ang II increases SGLT2 mRNA expression in HK-2 cells.

(A) HK-2 cells were cultured with increasing concentrations of Ang II, with and without losartan, for 24 hours and real-time qPCR for SGLT2 mRNA was performed. (B) The plasmid pGL4.20 hSGLT2 promoter (N-1986/N+22) was stably transfected to HK-2 cells, and the SGLT2 gene promoter activity was measured after treatment with different concentrations of Ang II, with and without losartan, by the luciferase activity assay. (C) HK-2 cells were cultured with Ang II (10−7 mol/L), with and without losartan (10−6 mol/L), for 24 hours. Immunostaining for SGLT2 (red) and DAPI staining (blue color, cellular nucleus) were performed (x600) Scale bars = 50 μm. (D) Semi-quantification of SGLT2 positive cells. The result is shown as a ratio of SGLT2-immunopositive cells /total counted cells. Each dot represents the ratio calculated from at least 20 cells. (E) HK-2 cells stably transfected with the plasmid pGL4.20 hSGLT2 promoter was treated with Ang II (10−7 mol/L) in the absence or presence of one of the following antioxidants: catalase (Cat), apocynin (APO) or diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI), and promoter activity was measured. (F) 2-NBDG glucose uptake in control cells and Ang II-treated cells with and without losartan. Statistical comparisons were performed using ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. Ctrl, control. Los, losartan. * p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Furthermore, SGLT2’s glucose transport activity was evaluated by the entry of fluorescence-labeled glucose 2-NBDG into the HK2 cells. Ang II significantly increased glucose uptake to the HK2 cells, which was abolished by losartan treatment (Figure 2F).

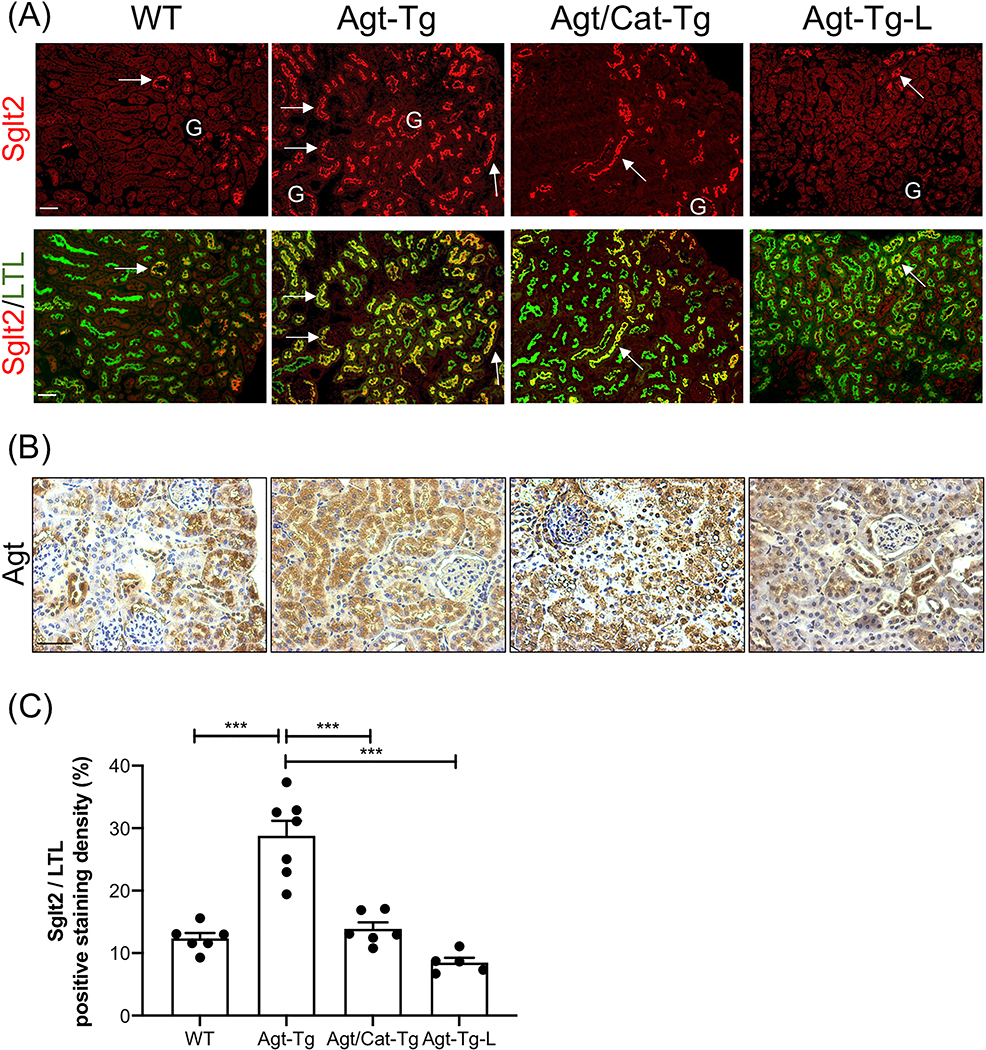

Increased Sglt2 expression in transgenic mice overexpressing Agt in the renal proximal tubule

We have generated Tg mice overexpressing Agt with and without Cat specifically in their RPTCs (Agt-Tg and Agt/Cat-Tg, respectively). Agt-Tg mice have a high risk of developing mild hypertension, albuminuria, and renal injury [19, 22, 35, 36], and these abnormalities are attenuated in Agt/Cat-Tg mice [21]. Figure 3A shows enhanced Sglt2-immunopositive staining in Agt-Tg compared with WT mice, and these increases were attenuated by Cat overexpression and abolished by losartan. Since increased urinary Ang II levels in Agt-Tg mice were attenuated by losartan treatment [22], we speculated that increased renal Ang II generated from up-regulated renal Agt (Figure 3B) likely stimulates SGLT2 expression via oxidative stress. Semi-quantitative analysis of Sglt2 immunostaining was consistent with this notion (Figure 3C).

Figure 3: Overexpression of Agt stimulates Sglt2 expression in proximal tubules.

(A) Double immunostaining of Sglt2 (red color, arrow) and a proximal tubular marker (lotus tetragonolobuslectin, LTL) (green color) in WT, angiotensinogen-transgenic (Agt-Tg), angiotensinogen/catalase-transgenic (Agt/Cat-Tg), and Agt-Tg mice treated with losartan (Agt-Tg-L) kidneys (x100). G, glomerulus. (B) Representative immunostaining for Agt in WT, Agt-Tg, Agt/Cat-Tg, and Agt-Tg treated with losartan (×200). (C)Semi-quantification of Sglt2/LTL immunostaining ratio. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Single-dose Ang II injection stimulates Sglt2 expression in mice

Next, we tested whether systemic Ang II injection could stimulate renal Sglt2 expression in vivo. WT mice received a single bolus injection of Ang II (1.44 mg/kg) or its vehicle (0.9% NaCl) subcutaneously (N=6/each group), and were euthanized 18 hours later (Figure 4A). A separate group of mice received losartan (15 mg/kg/day in the drinking water) for 7 days before the Ang II injection (N=6). Seven-day treatment with losartan did not affect SBP (115.9±1.6 mmHg without losartan, n=12 vs 116.2±4.7 mmHg with losartan, n=6). Injection of Ang II increased Sglt2 mRNA and protein expression (Figure 4B–D) and these changes were attenuated by losartan. Although up-regulated trend of Agt mRNA expression was observed, the change did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4B).

SGLT2 Inhibitor attenuates Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury in mice

Having shown that Ang II up-regulates SGLT2 expression, we investigated whether inhibition of SGLT2 could ameliorate Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury in mice. We administered high-dose Ang II (1,000 ng/kg/min, corresponding to 1.44 mg/kg/day) via subcutaneously-implanted osmotic minipumps in WT mice for 4 weeks. One week after initiating Ang II infusion, mice in Ang II-Cana group were started on an SGLT2i, canagliflozin (15 mg/kg/day) in the drinking water (Figure 5A). Control mice underwent sham surgery, and canagliflozin (15 mg/kg/day) was added to the drinking water one week after the sham surgery (Ctrl-Cana). Physiological and renal pathological changes in these 4 groups (N=8/group) were compared at week 4.

SBP was significantly higher in both the Ang II and Ang II-Cana groups (p<0.001) compared with controls; there was no detectable differences between SBP in the two groups (Figure 5B). Mice receiving Ang II infusion with or without canagliflozin had lower body weight (Figure 5C, p<0.001), consistent with the appetite suppressing action of high-dose Ang II [37, 38]. However, food intake was significantly higher in the Ang II-Cana group compared with the Ang II group, likely resulting from a compensation of the caloric loss from glycosuria (Table 3). Urine volume and water intake were significantly elevated in the Ang II-Cana group (Table 3). Urinary glucose concentration was similarly increased in mice treated with canagliflozin, regardless whether they received Ang II or not (Figure 5D), but the 24-hour urine glucose excretion was significantly increased in Ang II-Cana compared with Ctrl-Cana (Table 3). Blood glucose (BG) levels were not significantly changed among the 4 groups (Figure 5E). FeGlu was considerably higher in the Ang II-Cana group than in any other groups studied (Figure 5F). Ang II with and without Cana evoked increases in hematocrit (Table 3). As anticipated, urinary potassium excretion was increased in the Ang II-Cana group without causing detectable hypokalemia (Table 3). Ang II-Cana had significantly increased serum sodium level and electrolyte free water clearance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physiological parameters after 4 weeks of high-dose Ang II treatment in murine model

| Physiological parameters | Ctrl | Ctrl-Cana | Ang II | Ang II-Cana |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW (g) | 33.7 ± 1.2 | 31.1 ± 0.59 | 28.1 ± 1.3a | 26.9 ± 1.0b |

| SBP (mmHg) | 110 ± 4 | 111 ± 3 | 165 ± 7b,c | 158 ± 3b,c |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 708 ± 10 | 702 ± 10 | 615 ± 21b,c | 673 ± 9d |

| Food intake (mg/24h) | 214 ± 44 | 438 ± 68 | 191 ± 60 | 1023 ± 250a,e,f |

| Water intake (ml/24h) | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4a | 6.7 ± 0.7b,c,d |

| Urine volume (ul/24h) | 864 ± 114 | 1119 ± 72 | 1546 ± 402 | 3093 ± 677a,d,g |

| Urine glucose (mg/24h) | 0.32 ± 0.11 | 34.3 ± 9.7 | 1.09 ± 0.5 | 98.2 ± 29.5b,f,h |

| KW/TL (mg/mm) | 12.8 ± 0.4 | 13.4 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 0.6a,c | 12.0 ± 0.4 |

| KW/BW (mg/g) | 8.6 ± 0.4 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 0.5i |

| HW/TL (mg/mm) | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.2a,c | 6.5 ± 0.3a,c |

| HW/BW (mg/g) | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.3b,c | 5.8 ± 0.4b,c |

| GFR | 280.9 ± 19.5 | 226.0 ± 20.1 | 115.7 ± 22.3b,i | 145.9 ± 35.2a |

| Hematocrit (%) | 50.5 ± 0.8 | 50.1 ± 0.9 | 57.6 ± 1.4a | 60.7 ± 2.0b,c |

| BUN (mmol/L) † | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 13.2 ± 0.7 | 22.1 ± 2.3a | 24.0 ± 1.2b,c |

| Serum Creatinine (umol/L) † | 16.7 ± 2.1 | 15.3 ± 1.6 | 34.0 ± 8.2e,i | 26.0 ± 3.4 |

| Serum Na+ (mEq/L) † | 148.3 ± 1.1 | 154.7 ± 1.5h | 149.2 ± 2.1 | 156.0 ± 1.2a,d |

| Serum K+ (mEq/L) † | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| Urine Na+ (mEq/day) † | 61.6 ± 10.8 | 93.4 ± 14.9 | 65.6 ± 12.8 | 72.1 ± 17.5 |

| Urine K+ (mEq/day) † | 81.7 ± 12.0 | 130.8 ± 22.9 | 159.8 ± 25.1 | 185.2 ± 36.6i |

| FeNa (%)† | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 0.26 ± 0.07 |

| EFWC (ul/min) † | −0.09 ± 0.04 | −0.28 ± 0.13 | −0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.63 ± 0.33e |

BW, body weight; SBP, systolic blood pressure; KW, kidney weight; TL, tibia length; HW, heart weight; FeNa, Fractional sodium excretion; EFWC, electrolyte-free water clearance. N=8/group except for parameters with

which are N=6/group.

p<0.01 vs Ctrl

. p<0.001 vs Ctrl

p<0.001 vs Ctrl-Cana

p<0.05 vs Ang II

p<0.05 vs Ctrl-Cana

p<0.001 vs Ang II

p<0.01 vs Ctrl-Cana

p<0.05 vs Ctrl-Cana

p<0.05 vs Ctrl.

Ang II group had significantly lower GFR/BW ratio (Figure 5G), as well as significantly elevated serum creatinine and BUN levels (Table 3). Kidney weight (KW)/tibia length (TL) ratio was the lowest in the Ang II group. Canagliflozin did not reduce Ang II-induced increases in heart weight (HW) (Table 3). HW/BW strongly correlated with week 4 SBP regardless of the treatment (Supplementary Figure 1, r=0.69, p<0.001). At week 1, just before canagliflozin treatment was initiated, there was no difference in urinary albumin/creatinine ratio between control and Ang II group, 30.8 ± 7.7 μg/mg vs. 23.1 ± 7.8 μg/mg, respectively (N=6 in each group, NS). Urinary albumin excretion after 4 weeks was significantly increased in the Ang II group compared to Ctrl, and was attenuated in the Ang II-Cana group (Figure 5H). Ang II infusion evoked mesangial expansion, glomerulosclerosis, and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and these changes were partially reversed by canagliflozin treatment (Figure 6A–D).

Figure 6: Histological analyses of mice kidneys after 4 weeks of high-dose Ang II infusion with and without canagliflozin.

(A) Representative images of Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining in outer cortex and cortico-medullary junction (x200), (B) Sirius red staining (x200 and x600) of the mouse kidneys from 4 treatment groups. Sclerosed glomeruli (arrowhead), mesangial expansion (large arrow), tubular casts (small arrow), and glomerular and tubulointerstitial fibrosis (Sirius red staining) were observed in Ang II group, and these changes were partially reversed by canagliflozin treatment (Ang II-Cana). (C) Glomerulosclerotic index; each dot represents a score calculated from at least 60 glomerular sections in each mouse. (D) Semi-quantification of Sirius-red positive area. Values are means ± SEM, n = 4–6 for each group. *p<0.05. ***p<0.005. NS, not significant. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Unexpectedly, Sglt2 and Agt expressions were similar in the groups studied (Figure 7A–C). Renal Ang II expression and urinary Ang II excretion were similarly increased in Ang II-infused mice with or without canagliflozin treatment (Figure 7B, C). Fibronectin 1 (FN1) mRNA was significantly increased in Ang II, and was attenuated in Ang II-Cana (Figure 7A).

Figure 7: Sglt2 expression of mouse kidneys following 4 weeks of high-dose Ang II infusion with and without canagliflozin.

(A) RT-qPCR of Sglt2, Agt, and FN1 in isolated renal proximal tubule cells. (B) Representative microphotographs of immunostainings of Sglt2 (red color, arrow, x100), Sglt2 merged with LTL (green color), and immunohistochemistry of Ang II (x200). G, glomerulus. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C) Semi-quantification of Sglt2/LTL ratio in 4 treatment groups. Values are means ± SEM, n = 6/ each group. NS, not significant. (D) Urinary Ang II excretion per day. Values are means ± SEM, n = 6–7/ each group. *p<0.05.

Discussion

Our findings show that changes in the activity of the intrarenal RAS are positively correlated with changes in endogenous SGLT2 expression levels. Consequently, our results also show that SGLT2i can ameliorate Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury in mice, the most widely used preclinical model of human hypertensive nephrosclerosis [39]. Compelling evidence suggests a pivotal role for inappropriately activated intrarenal RAS in the pathogenesis of human hypertensive kidney injury [19, 36, 40]. Our findings may potentially lead to a new treatment option for hypertensive nephrosclerosis, which is the second most common cause of CKD and end-stage kidney disease in the world [41].

Here, we demonstrated that Ang II dose-dependently increases SGLT2 expression in vitro, and that Agt-Tg mice as well as WT mice treated with a bolus injection of Ang II have up-regulated Sglt2 expression. These findings are consistent with previous findings of Bautista et al. [42], who reported increased Sglt2 expression in rats with aortic coarctation, a model of renovascular hypertension, and rats with low-dose Ang II infusion. Moreover, we demonstrated the inhibitory role of antioxidants on the stimulation Sglt2 expression by Ang II in HK-2 cells and in Agt/Cat-Tg mice, indicating increased oxidative stress or ROS generation may mediate the stimulatory effect of Ang II on Sglt2 expression.

In contrast to the effects of bolus injection of Ang II, chronic Ang II infusion (1000 ng/kg/min subcutaneously for 4 weeks) resulted in no detectable increases in Sglt2 expression. The reasons for these apparently contradictory observations are not clear at present. One possibility is that sustained stimulation of AT1R by Ang II led to desensitization of AT1R, as has been reported in many models for cardiovascular disease [43, 44]. SGLT2’s biphasic response to different concentrations of Ang II was also observed in our in vitro study as Ang II at 10−5 M inhibited SGLT2 mRNA expression. Another possibility might be that Sglt2 expression is affected by pressure natriuresis response, similar to Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3), another sodium transporter in the proximal tubules. It has been reported that a short-term low-dose Ang II (200 ng/kg/min for 3 days) in rats, which did not affect SBP, increased the expression of NHE3 [45], whereas an intermediate-dose of Ang II (400 ng/kg/min for 14 days), which evoked hypertension, decreased the abundance of NHE3 [46]. This notion is further supported by our result from the NEPTUNE study, where we detected positive correlations between RAS genes and SGLT2 in a patient population with well-controlled BP (mean SBP: 124 ± 2 mmHg). Another possibility is that higher doses of Ang II might have caused tubular damage, thereby leading to Sglt2 down-regulation. Studies on streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes mice have reported down-regulated Sglt2 expression, whereas other studies with genetically modified diabetic models have found increased Sglt2 expression [12]. It has been hypothesized that reduced Sglt2 expression might have occurred secondary to the tubular toxicity of STZ [47]. Lower Sglt2 expression has also been reported following ischemia-reperfusion-induced tubular cell injury in mice [48].

The chronic high-dose Ang II infusion did not alter intrarenal Agt expression in this study, which supports a previous finding by Gonzalez-Villalobos, et al. demonstrating that 1,000 ng/kg/min of Ang II infusion for 12 days did not increase intrarenal Agt expression levels while 400 ng/kg/min of Ang II infusion enhanced the Agt expression. Though we were aware of their findings, we needed to use higher-dose of Ang II to detect renal pathological changes by Ang II in C57BL/6 mice which are known to be relatively resistant to kidney injury [49].

The present study showed that canagliflozin prevented Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury in mice. It has been proposed that the potential mechanisms of renoprotection with SGLT2i include improved renal hemodynamics via tubule-glomerular feedback [50], lowered systemic hypertension [51], and direct anti-fibrotic effects [52, 53]. In our study, canagliflozin did not lower GFR or systemic blood pressure in mice with Ang II infusion. However, it decreased glomerular and tubulointerstitial fibrosis shown in pathology as well as profibrotic gene expressions in isolated RPTCs. Therefore, it can be speculated that canagliflozin prevented renal damage by Ang II via anti-fibrotic effects.

It is important to note that the Ang II-Cana group had significantly higher FeGlu than Ctrl-Cana, indicating that the glycosuric effect of canagliflozin was enhanced by co-administration of Ang II compared with the effects of canagliflozin in euglycemice mice. These findings would suggest that the effects of SGLT2i may not necessarily correlate with SGLT2 mRNA or protein expression. Indeed, Ang II may directly enhance the effect of SGLT2i. It has been proposed that increased SGLT2 expression would render SGLT2 an attractive target for inhibition, thus increasing the efficacy of the inhibitors [14, 48, 54]. To date, several retrospective studies, which were conducted to determine the clinical parameters for monitoring the therapeutic efficacy of SGLT2i in type 2 diabetes patients, consistently indicated that higher initial HbA1c and eGFR are associated with a better glycemic response [55–57]. Identifying intrarenal RAS as one of the determinants of the efficacy of SGLT2i is of clinical relevance for glucose control in type 2 diabetes patients.

Another novel aspect of the present study is that the diuretic action of canagliflozin was enhanced by Ang II. Indeed, Ang II-Cana mice had the highest urine volume, water intake, serum sodium level, electrolyte free water clearance, and hematocrit among the groups studied. Previous literatures have shown that Ang II stimulates thirst [58] and increases urine output [59], and SGLT2i induces osmotic diuresis and natriuresis [60]. It appears the combination of both has an additive effects, which has important clinical implications. It has been suggested that the hematocrit increasing effect of SGLT2i is one of the most important mediators of the reduction in cardiovascular death with SGLT2i versus placebo [61, 62]. Recently, the landmark placebo-controlled clinical trial DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure) [63] reported reduced heart failure (HF) and mortality in patients with chronic HF treated with dapaglifozin. Intriguingly, the benefits were observed irrespective of diabetes status. It is widely acknowledged that RAS plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of HF [64]. HF is associated with activation of both systemic and intrarenal RAS, which, in turn, affects the mortality and morbidity [65–67]. These would argue for therapeutic use of SGLT2i under conditions of increased RAS.

Another important finding is the analysis of the large human kidney gene database of the NEPTUNE cohort. We detected significant positive correlations of AGT, renin, and ACE gene expressions with SGLT2 mRNA expression. In multivariable analysis, those factors previously reported to correlate with SGLT2 expression in human kidneys, such as interstitial fibrosis and eGFR [14], were no longer associated with SGLT2 after adjustment for RAS gene expression. Since AGT is the sole precursor of all angiotensin peptides and renin is the rate-limiting enzyme to generate Ang II, we surmise that the downstream molecule Ang II is likely an important regulator of SGLT2 expression in human kidneys.

Our study has several limitations. First, the molecular mechanism of SGLT2 regulation by ROS remains to be investigated. Second, we could not directly analyze the relation between renal Ang II level and SGLT2 expression in the human biopsy material. Though RAS blocker use was not associated with SGLT2 expression in NEPTUNE participants, we don’t know how much of the generated RAS was successfully blocked by RAS blockers they were taking. Third, our chronic Ang II infusion study did not include a group that was treated simultaneously with a RAS blocker and SGLT2i.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates a link between intrarenal RAS and SGLT2 expression both in humans and mice. Consistently, treatment with SGLT2i effectively attenuated Ang II-induced hypertensive renal injury in mice independent of changes in SBP. Our data provide a rational basis for future clinical studies of SGLT2i in non-diabetic kidney disease. Further understanding of the mechanism of SGLT2 regulation has clinical relevance and provides important insights into the reno- and cardio-protective actions of SGLT2i.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Hypertensive nephrosclerosis, the second most common cause of chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease in the world, is associated with an inappropriately activated intrarenal RAS.

Our present study demonstrates an association between intrarenal RAS and SGLT2 expression both in humans and mice.

SGLT2 inhibitors might have a role for the prevention and/or treatment of hypertension-associated deterioration of kidney function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-84363 and MOP-142378 to JSDC, MOP-86450 to SLZ, and MOP-97742 to JGF), Kidney Foundation of Canada (KFOC 170006 to JSDC). KNM is a recipient of a fellowship from the Consortium de Néphrologie de l’Université de Montréal (2018–2019) and Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship Program of the American Society of Nephrology (2019–2020).

The Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network Consortium (NEPTUNE), U54-DK-083912, is a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), supported through a collaboration between the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases. Additional funding and/or programmatic support for this project has also been provided by the University of Michigan, the NephCure Kidney International and the Halpin Foundation.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Footnotes

Disclosure

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Perkovic V, Jardine M, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink H, Charytan D, et al. : Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med, 380: 2295–2306, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wanner C, Inzucchi S, Lachin J, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, et al. : Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med, 375: 323–334, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, Rozenberg A, Yanuv I, Goodrich EL, et al. : Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 7: 606–617, 2019. 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30180-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidokoro K, Cherney D, Bozovic A, Nagasu H, Satoh M, Kanda E, et al. : Evaluation of Glomerular Hemodynamic Function by Empagliflozin in Diabetic Mice Using In Vivo Imaging. Circulation, 140: 303–315, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Bommel EJM, Lytvyn Y, Perkins BA, Soleymanlou N, Fagan NM, Koitka-Weber A, et al. : Renal hemodynamic effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in hyperfiltering people with type 1 diabetes and people with type 2 diabetes and normal kidney function. Kidney Int, 97: 631–635, 2020. 10.1016/j.kint.2019.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirklbauer M, Schupart R, Fuchs L, Staudinger P, Corazza U, Sallaberger S, et al. : Unraveling reno-protective effects of SGLT2 inhibition in human proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 316: F449–462, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimoto T, Furuki T, Kobori H, Miyakawa M, Imachi H, Murao K, et al. : Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on urinary excretion of intact and total angiotensinogen in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Investig Med, 65: 1057–1061, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maki T, Maeno S, Maeda Y, Yamato M, Sonoda N, Ogawa Y, et al. : Amelioration of diabetic nephropathy by SGLT2 inhibitors independent of its glucose-lowering effect: A possible role of SGLT2 in mesangial cells. Sci Rep, 9: 4703, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dekkers CCJ, Gansevoort RT: Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: extending the indication to non-diabetic kidney disease? Nephrol Dial Transplant, 35: i33–i42, 2020. 10.1093/ndt/gfz264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heerspink HJL, Stefansson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, et al. : Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med, 383 : 1436–1446, 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherney DZI, Dekkers CCJ, Barbour SJ, Cattran D, Abdul Gafor AH, Greasley PJ, et al. : Effects of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on proteinuria in non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease (DIAMOND): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 8: 582–593, 2020. 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30162-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallon V, Rose M, Gerasimova M, Satriano J, Platt KA, Koepsell H, et al. : Knockout of Na-glucose transporter SGLT2 attenuates hyperglycemia and glomerular hyperfiltration but not kidney growth or injury in diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 304: F156–167, 2013. 10.1152/ajprenal.00409.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Levi J, Luo Y, Myakala K, Herman-Edelstein M, Qiu L, et al. : SGLT2 Protein Expression Is Increased in Human Diabetic Nephropathy. J Biol Chem, 292: 5335–5348, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan Sridhar V, Ambinathan JPN, Kretzler M, Pyle LL, Bjornstad P, Eddy S, et al. : Renal SGLT mRNA expression in human health and disease: a study in two cohorts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 317: F1224–F1230, 2019. 10.1152/ajprenal.00370.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo C, Miyata K, Zhao S, Ghosh A, Chang S, Chenier I, et al. : Tubular Deficiency of Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein F Elevates Systolic Blood Pressure and Induces Glycosuria in Mice. Sci Rep, 9: 15765, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyata KN, Zhao S, Wu CH, Lo CS, Ghosh A, Chenier I, et al. : Comparison of the Effects of Insulin and SGLT2 Inhibitor on the Renal Renin-Angiotensin System in Type 1 Diabetes Mice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract: 108107, 2020 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lau GJ, Godin N, Maachi H, Lo CS, Wu SJ, Zhu JX, et al. : Bcl-2-modifying factor induces renal proximal tubular cell apoptosis in diabetic mice. Diabetes, 61: 474–484, 2012. 10.2337/db11-0141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu YT, Ma XL, Xu YH, Hu J, Wang F, Qin WY, et al. : A Fluorescent Glucose Transport Assay for Screening SGLT2 Inhibitors in Endogenous SGLT2-Expressing HK-2 Cells. Nat Prod Bioprospect, 9: 13–21, 2019. 10.1007/s13659-018-0188-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, et al. : RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int, 69: 1016–1023, 2006. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brezniceanu ML, Liu F, Wei CC, Tran S, Sachetelli S, Zhang SL, et al. : Catalase overexpression attenuates angiotensinogen expression and apoptosis in diabetic mice. Kidney Int, 71: 912–923, 2007. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godin N, Liu F, Lau GJ, Brezniceanu ML, Chenier I, Filep JG, et al. : Catalase overexpression prevents hypertension and tubular apoptosis in angiotensinogen transgenic mice. Kidney Int, 77: 1086–1097, 2010. 10.1038/ki.2010.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SY, Lo CS, Zhao XP, Liao MC, Chenier I, Bouley R, et al. : Overexpression of angiotensinogen downregulates aquaporin 1 expression via modulation of Nrf2-HO-1 pathway in renal proximal tubular cells of transgenic mice. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst, 17, 2016 10.1177/1470320316668737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Seth DM, Satou R, Horton H, Ohashi N, Miyata K, et al. : Intrarenal angiotensin II and angiotensinogen augmentation in chronic angiotensin II-infused mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 295: F772–779, 2008. 10.1152/ajprenal.00019.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali BH, Al Salam S, Al Suleimani Y, Al Za’abi M, Abdelrahman AM, Ashique M, et al. : Effects of the SGLT-2 Inhibitor Canagliflozin on Adenine-Induced Chronic Kidney Disease in Rats. Cell Physiol Biochem, 52: 27–39, 2019. 10.33594/000000003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdo S, Lo C, Chenier I, Shamsuyarova A, Filep J, Ingelfinger J, et al. : Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins F and K mediate insulin inhibition of renal angiotensinogen gene expression and prevention of hypertension and kidney injury in diabetic mice. Diabetologia, 56: 1649–1660, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi Z, Whitt I, Mehta A, Jin J, Zhao M, Harris R, et al. : Serial determination of glomerular filtration rate in conscious mice using FITC-inulin clearance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 286: F590–596, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallon V, Platt K, Cunard R, Schroth J, Whaley J, Thomson S, et al. : SGLT2 mediates glucose reabsorption in the early proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol, 22: 104–112, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung S, Kim S, Son M, Kim M, Koh ES, Shin SJ, et al. : Empagliflozin Contributes to Polyuria via Regulation of Sodium Transporters and Water Channels in Diabetic Rat Kidneys. Front Physiol, 10: 271, 2019. 10.3389/fphys.2019.00271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maric C, Sandberg K, Hinojosa-Laborde C: Glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis are attenuated with 17beta-estradiol in the aging Dahl salt sensitive rat. J Am Soc Nephrol, 15: 1546–1556, 2004. 10.1097/01.asn.0000128219.65330.ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasser JM, Moningka NC, Cunningham MW Jr., Croker B, Baylis C: Asymmetric dimethylarginine in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 298: R740–746, 2010. 10.1152/ajpregu.90875.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou LX, Imig JD, von Thun AM, Hymel A, Ono H, Navar LG: Receptor-mediated intrarenal angiotensin II augmentation in angiotensin II-infused rats. Hypertension, 28: 669–677, 1996. 10.1161/01.hyp.28.4.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gipson DS, Troost JP, Lafayette RA, Hladunewich MA, Trachtman H, Gadegbeku CA, et al. : Complete Remission in the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 11: 81–89, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.02560315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gadegbeku CA, Gipson DS, Holzman LB, Ojo AO, Song PX, Barisoni L, et al. : Design of the Nephrotic Syndrome Study Network (NEPTUNE) to evaluate primary glomerular nephropathy by a multidisciplinary approach. Kidney Int, 83: 749–756, 2013. 10.1038/ki.2012.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariani LH, Martini S, Barisoni L, Canetta PA, Troost JP, Hodgin JB, et al. : Interstitial fibrosis scored on whole-slide digital imaging of kidney biopsies is a predictor of outcome in proteinuric glomerulopathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 33: 310–318, 2018. 10.1093/ndt/gfw443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo C, Liu F, Shi Y, Maachi H, Chenier I, Godin N, et al. : Dual RAS blockade normalizes angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 expression and prevents hypertension and tubular apoptosis in Akita angiotensinogen-transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 302: F840–852, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu F, Wei CC, Wu SJ, Chenier I, Zhang SL, Filep JG, et al. : Apocynin attenuates tubular apoptosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in transgenic mice independent of hypertension. Kidney Int, 75: 156–166, 2009. 10.1038/ki.2008.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida T, Semprun-Prieto L, Wainford RD, Sukhanov S, Kapusta DR, Delafontaine P: Angiotensin II reduces food intake by altering orexigenic neuropeptide expression in the mouse hypothalamus. Endocrinology, 153: 1411–1420, 2012. 10.1210/en.2011-1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez AA, Liu L, Lara LS, Seth DM, Navar LG, Prieto MC: Angiotensin II stimulates renin in inner medullary collecting duct cells via protein kinase C and independent of epithelial sodium channel and mineralocorticoid receptor activity. Hypertension, 57: 594–599, 2011. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.165902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lerman LO, Kurtz TW, Touyz RM, Ellison DH, Chade AR, Crowley SD, et al. : Animal Models of Hypertension: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension, 73: e87–e120, 2019. 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffin KA: Hypertensive Kidney Injury and the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Hypertension, 70: 687–694, 2017. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.08314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, et al. : Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet, 382: 260–272, 2013. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bautista R, Manning R, Martinez F, Avila-Casado Mdel C, Soto V, Medina A, et al. : Angiotensin II-dependent increased expression of Na+-glucose cotransporter in hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 286: F127–133, 2004. 10.1152/ajprenal.00113.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hein L, Meinel L, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Kobilka BK: Intracellular trafficking of angiotensin II and its AT1 and AT2 receptors: evidence for selective sorting of receptor and ligand. Mol Endocrinol, 11: 1266–1277, 1997. 10.1210/mend.11.9.9975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Godoy MA, de Oliveira AM, Rattan S: Angiotensin II-induced relaxation of anococcygeus smooth muscle via desensitization of AT1 receptor, and activation of AT2 receptor associated with nitric-oxide synthase pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 311: 394–401, 2004. 10.1124/jpet.104.069856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen MT, Han J, Ralph DL, Veiras LC, McDonough AA: Short-term nonpressor angiotensin II infusion stimulates sodium transporters in proximal tubule and distal nephron. Physiol Rep, 3, 2015 10.14814/phy2.12496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen MT, Lee DH, Delpire E, McDonough AA: Differential regulation of Na+ transporters along nephron during ANG II-dependent hypertension: distal stimulation counteracted by proximal inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 305: F510–519, 2013. 10.1152/ajprenal.00183.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brouwers B, Pruniau VP, Cauwelier EJ, Schuit F, Lerut E, Ectors N, et al. : Phlorizin pretreatment reduces acute renal toxicity in a mouse model for diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem, 288: 27200–27207, 2013. 10.1074/jbc.M113.469486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nespoux J, Patel R, Zhang H, Huang W, Freeman B, Sanders PW, et al. : Gene knockout of the Na(+)-glucose cotransporter SGLT2 in a murine model of acute kidney injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 318: F1100–F1112, 2020. 10.1152/ajprenal.00607.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leelahavanichkul A, Yan Q, Hu X, Eisner C, Huang Y, Chen R, et al. : Angiotensin II overcomes strain-dependent resistance of rapid CKD progression in a new remnant kidney mouse model. Kidney Int, 78: 1136–1153, 2010. 10.1038/ki.2010.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cherney D, Perkins B, Soleymanlou N, Maione M, Lai V, Lee A, et al. : Renal hemodynamic effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation, 129: 587–597, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazidi M, Rezaie P, Gao HK, Kengne AP: Effect of Sodium-Glucose Cotransport-2 Inhibitors on Blood Pressure in People With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 43 Randomized Control Trials With 22 528 Patients. J Am Heart Assoc, 6, 2017 10.1161/JAHA.116.004007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panchapakesan U, Pegg K, Gross S, Komala MG, Mudaliar H, Forbes J, et al. : Effects of SGLT2 inhibition in human kidney proximal tubular cells--renoprotection in diabetic nephropathy? PLoS One, 8: e54442, 2013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang F, Zhao Y, Wang Q, Hillebrands J, van den Born J, Ji L, et al. : Dapagliflozin Attenuates Renal Tubulointerstitial Fibrosis Associated With Type 1 Diabetes by Regulating STAT1/TGFβ1 Signaling. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 10: 441, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rajasekeran H, Reich HN, Hladunewich MA, Cattran D, Lovshin JA, Lytvyn Y, et al. : Dapagliflozin in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a combined human-rodent pilot study. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 314: F412–F422, 2018. 10.1152/ajprenal.00445.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cho YK, Lee J, Kang YM, Yoo JH, Park JY, Jung CH, et al. : Clinical parameters affecting the therapeutic efficacy of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One, 14: e0220667, 2019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JY, Cho Y, Lee M, Kim YJ, Lee YH, Lee BW, et al. : Predictors of the Therapeutic Efficacy and Consideration of the Best Combination Therapy of Sodium-Glucose Co-transporter 2 Inhibitors. Diabetes Metab J, 43: 158–173, 2019. 10.4093/dmj.2018.0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yagi S, Aihara KI, Kondo T, Kurahashi K, Yoshida S, Endo I, et al. : Predictors for the Treatment Effect of Sodium Glucose Co-transporter 2 Inhibitors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Adv Ther, 35: 124–134, 2018. 10.1007/s12325-017-0639-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzsimons JT: Angiotensin, thirst, and sodium appetite. Physiol Rev, 78: 583–686, 1998. 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li XC, Zhu D, Chen X, Zheng X, Zhao C, Zhang J, et al. : Proximal Tubule-Specific Deletion of the NHE3 (Na(+)/H(+) Exchanger 3) in the Kidney Attenuates Ang II (Angiotensin II)-Induced Hypertension in Mice. Hypertension, 74: 526–535, 2019. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Masuda T, Muto S, Fukuda K, Watanabe M, Ohara K, Koepsell H, et al. : Osmotic diuresis by SGLT2 inhibition stimulates vasopressin-induced water reabsorption to maintain body fluid volume. Physiol Rep, 8: e14360, 2020. 10.14814/phy2.14360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inzucchi SE, Zinman B, Fitchett D, Wanner C, Ferrannini E, Schumacher M, et al. : How Does Empagliflozin Reduce Cardiovascular Mortality? Insights From a Mediation Analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Diabetes Care, 41: 356–363, 2018. 10.2337/dc17-1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marathias KP, Lambadiari VA, Markakis KP, Vlahakos VD, Bacharaki D, Raptis AE, et al. : Competing Effects of Renin Angiotensin System Blockade and Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on Erythropoietin Secretion in Diabetes. Am J Nephrol, 51: 349–356, 2020. 10.1159/000507272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Kober L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al. : Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N Engl J Med, 381: 1995–2008, 2019. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borghi C, Force ST, Rossi F, Force SIFT: Role of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System and Its Pharmacological Inhibitors in Cardiovascular Diseases: Complex and Critical Issues. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev, 22: 429–444, 2015. 10.1007/s40292-015-0120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eiskjaer H, Bagger JP, Danielsen H, Jensen JD, Jespersen B, Thomsen K, et al. : Mechanisms of sodium retention in heart failure: relation to the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Am J Physiol, 260: F883–889, 1991. 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.6.F883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orscelik O, Ozkan B, Arslan A, Sahin EE, Sakarya O, Surmeli OA, et al. : Relationship between intrarenal renin-angiotensin activity and re-hospitalization in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Anatol J Cardiol, 19: 205–212, 2018. 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2018.68726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Group CTS: Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med, 316: 1429–1435, 1987. 10.1056/NEJM198706043162301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.