Abstract

Manganese (Mn) serves as an essential cofactor for many enzymes in various compartments of a plant cell. Allocation of Mn among various organelles thus plays a central role in Mn homeostasis to support metabolic processes. We report the identification of a Golgi-localized Mn transporter (named PML3) that is essential for rapid cell elongation in young tissues such as emerging leaves and the pollen tube. In particular, the pollen tube defect in the pml3 loss-of-function mutant caused severe reduction in seed yield, a critical agronomic trait. Further analysis suggested that a loss of pectin deposition in the pollen tube might cause the pollen tube to burst and slow its elongation, leading to decreased male fertility. As the Golgi apparatus serves as the major hub for biosynthesis and modification of cell-wall components, PML3 may function in Mn homeostasis of this organelle, thereby controlling metabolic and/or trafficking processes required for pectin deposition in rapidly elongating cells.

Key words: manganese transport, Golgi, pollen tube, cell wall

A Golgi-localized Mn transporter is essential for pectin deposition in the cell wall of the pollen tube, affecting tip growth and male fertility.

Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is an essential micronutrient in all life forms. As a cofactor of numerous enzymes, Mn plays a key role in diverse metabolic pathways, including antioxidant defense, protein modification, and carbohydrate and nucleic acid metabolism (Broadley et al., 2012). In plants, Mn is particularly important because it serves as the central atom of the oxygen-evolving complex that catalyzes the water-splitting reaction in photosynthesis (Shen, 2015). Despite these necessary roles, Mn excess is detrimental to plants, especially in acidic soils. Therefore, plants must control intracellular Mn levels with various Mn transporters to achieve optimal Mn homeostasis.

To date, multiple Mn transporters have been characterized as responsible for Mn uptake and distribution in plants. The natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (NRAMP) family and the zinc-regulated transporter/iron-regulated transporter-related protein (ZIP) family are involved in Mn influx into the cytosol. The metal transport protein (MTP) family, P-type ATPases family, vacuolar iron transporter family, Ca2+/cation antiporter superfamily, and uncharacterized protein family 0016 (UPF0016) mediate the export of Mn from the cytosol (Socha and Guerinot, 2014; Alejandro et al., 2020). In Arabidopsis, NRAMP1 is localized in the plasma membrane of root cells and functions as a high-affinity Mn transporter for Mn acquisition from the soil under low-Mn conditions (Cailliatte et al., 2010). Another plasma membrane transporter, IRT1, collaborates with NRAMP1 in the uptake of Mn and Fe (Castaings et al., 2016). In addition, two members of the ZIP family, ZIP1 and ZIP2, which are localized in the vacuolar and plasma membranes, respectively, are involved in Mn translocation from the root to the shoot (Milner et al., 2013). For intracellular Mn allocation to various organelles, NRAMP2 is a trans-Golgi network (TGN)-localized transporter that functions in root growth and photosynthesis, especially under Mn deficiency (Alejandro et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018). The tonoplast-localized NRAMP3 and NRAMP4 play crucial roles in both the release of Fe from vacuoles during seed germination under Fe deficiency and the export of vacuolar Mn in the photosynthetic tissues of adult plants under Mn deficiency (Thomine et al., 2003; Lanquar et al., 2005, 2010; Mary et al., 2015). In the chloroplast, chloroplast manganese transporter 1 (CMT1) and photosynthesis-affected mutant 71 (PAM71) were reported to be Mn transporters that mediate Mn uptake into the chloroplast and thylakoid sequentially (Schneider et al., 2016; Eisenhuta et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018).

In addition, excess Mn in plant cells is sequestered in the vacuole, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi. Two MTP family proteins, tonoplast-localized AtMTP8 and TGN/prevacuolar compartment (PVC)-localized AtMTP11, confer Mn tolerance (Delhaize et al., 2007; Peiter et al., 2007; Eroglu et al., 2016). The P2A-type ATPases ECA1 and ECA3 mediate the deposition of excess Mn from the cytosol into the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, respectively (Wu et al., 2002; Li et al., 2008; Mills et al., 2008).

The chloroplast Mn transporters CMT1 and PAM71 belong to the evolutionarily conserved UPF0016 family, which has five members in Arabidopsis (Supplemental Figure 1A). In this study, we demonstrate that another member of the UPF0016 family in Arabidopsis, PML3 (photosynthesis-affected mutant 71-like 3, AT5G36290) (Hoecker et al., 2020), is a cis-Golgi-localized Mn transporter that plays a key role in Mn homeostasis and is crucial for leaf and pollen tube growth.

Results

PML3 is a putative Mn transporter localized in the Golgi apparatus

Members of the UPF0016 family are evolutionarily conserved and are characterized by one or two copies of the E-Ф-G-D-(KR)-(TS) consensus motif. There is only one member in yeast (GDT1) and human (TMEM165), and it functions as a Mn2+/Ca2+ transporter in the Golgi apparatus (Demaegd et al., 2013; Potelle et al., 2016, 2017). The UPF0016 proteins have expanded into a five-member family in Arabidopsis (Supplemental Figure 1A), and PML3 is the closest homolog to yeast GDT1 and human TMEM165 (Zhang et al., 2018).

To explore the cellular mechanism of PML3-mediated transport, we examined its subcellular localization. The PML3 gene is predicted to encode a transmembrane protein with a signal peptide for the secretory pathway (Supplemental Figure 1B and 1C). A proteomics analysis identified PML3 as a protein enriched in the Golgi membrane fraction (Parsons et al., 2012). To examine the subcellular localization of PML3, we constructed an expression vector containing a PML3–GFP fusion under the control of the 35S promoter and transiently expressed the fusion protein in Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. Confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis showed a punctate distribution of green fluorescent signal in the protoplasts, suggesting that PML3 may be associated with endomembrane compartments (Figure 1A). To further identify the intracellular punctate structures in which PML3–GFP is localized, we coexpressed PML3–GFP with endosomal markers, including the cis-Golgi marker, Man1–mCherry; the TGN marker, SYP61–mCherry; and the PVC marker, VSR2–RFP. We found that the punctate green fluorescence of PML3–GFP colocalized with Man1–mCherry, a cis-Golgi marker, but did not overlap with SYP61–mCherry or VSR2–RFP (Figure 1B). These results indicated that PML3 is localized in the cis-Golgi apparatus.

Figure 1.

PML3 is localized in the Golgi apparatus.

(A)Arabidopsis protoplasts were transiently transformed with GFP (top) and PML3–GFP (bottom). Scale bars, 20 μm. Columns from left to right show GFP signals, chlorophyll autofluorescence, merged images of GFP and chlorophyll (Merged), and bright-field differential interference contrast.

(B) PML3–GFP was coexpressed with Man1–mCherry (top), SYP61–mCherry (middle), and VSR2–RFP (bottom) fusion proteins in Arabidopsis protoplasts. Columns from left to right show GFP signals, RFP signals, merged images of GFP and RFP (Merged), 5× enlargement of a randomly selected area of merged images (5×Enlarged), and differential interference contrast (DIC). Colocalization from column 3 is depicted as relative intensity (x and y axes) scatterplots. Values of rp and rs coefficients were calculated and are shown next to the scatterplots. Scale bars, 20 μm.

To examine the expression pattern of the PML3 gene in Arabidopsis plants, we performed a quantitative real-time PCR assay and found that PML3 mRNA was expressed ubiquitously (Figure 2A). In addition, we found that the mRNA level of PML3 was higher in young leaves than in old leaves (Figure 2B). To assess the expression pattern of PML3 in detail, we constructed a PML3 promoter-driven GUS reporter and introduced it into wild-type (WT) plants. GUS staining revealed that the PML3 gene promoter was active in leaves, roots, flowers, siliques, and pollen tubes (Figure 2C). Consistent with the quantitative real-time PCR assay, young leaves expressed higher levels of GUS than old leaves. These results suggested that PML3 expression is widespread and particularly strong in rapidly growing tissues such as root tips, young leaves, and pollen tubes.

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of the PML3 gene.

(A) Relative expression levels of PML3 in different tissues (roots, stems, rosette leaves, cauline leaves, flowers, and siliques) of 6-week-old WT plants grown in hydroponic culture medium.

(B) Relative expression levels of PML3 in roots, old leaves, and young leaves. The expression level was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. ACTIN2 was used as an internal standard. Data are means ± SD. n = 3.

(C) Expression pattern of PML3pro::GUS in transformed Arabidopsis plants at different growth stages and tissues: (a) 2 days, (b) 3 days, (c) 5 days, (d) 7 days, (e) 10 days, (f) 14 days, (g) 21 days, (h) inflorescence, (i) pollen grain, (j–l) pollen tube, and (m–p) silique. Scale bars: 50 μm in (i); 100 μm in (j), (k), and (l); 500 μm in (a) and (b); 1 mm in (c), (h), (m), and (n); 2 mm in (d), (e), (f), (o), and (p); 1 cm in (g).

PML3 complements the growth defect of the yeast mutant Δsmf1 under Mn-limited conditions

Our previous study indicated that CMT1, a member of the UPF0016 family, complemented growth defects of the yeast mutant Δsmf1, which is deficient in Mn2+ uptake (Zhang et al., 2018), suggesting that CMT1 transports Mn. We speculated that PML3 might be a novel Mn transporter in the Golgi. We used a similar yeast complementation assay to confirm its function as a Mn transporter. We cloned PML3 into the pYES2 vector and introduced it into Δsmf1 yeast cells. When the medium contained 20 mM EGTA, Δsmf1 cells containing the pYES2 empty vector (Δsmf1 + pYES2) or the pYES2 vector harboring PML3 (Δsmf1 + PML3) failed to grow. Because PML3 is a Golgi protein, the full-length PML3 was indeed located in punctate structures in the yeast cells (Supplemental Figure 2). We then deleted the signal peptide of PML3 so that it would be integrated into the plasma membrane, where it could transport Mn into the cell, thereby complementing the Mn-uptake defect in the mutant cells. As expected, the truncated version of PML3 lacking a signal peptide at the N terminus (Δsmf1 + ΔN25PML3) complemented the growth defect of Δsmf1 on medium containing 20 mM EGTA (Figure 3A). Growth-curve analysis using liquid culture also consistently showed that the truncated version of PML3 supported the growth of yeast cells under Mn-limited conditions (Figure 3B). In addition, Δsmf1 cells expressing the truncated version of PML3 accumulated more Mn than the control cells under both Mn-sufficient and Mn-deficient conditions (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results confirmed that PML3 mediates Mn transport.

Figure 3.

PML3-mediated complementation of growth deficiency in Δsmf1.

(A) Empty vector (Δsmf1 + pYES2), PML3 (Δsmf1 + PML3), truncated ΔN25PML3 (Δsmf1 + ΔN25PML3), and IRT1 (Δsmf1 + IRT1) were introduced into the yeast mutant strain Δsmf1. Δsmf1 + pYES2 was the negative control, and Δsmf1 + IRT1 was the positive control. Yeast cells were grown on synthetic medium without uracil (SC-U), containing galactose, in the absence or presence of the Mn2+ chelator EGTA with the addition of extra Mn2+ or Ca2+. The concentrations of EGTA, Mn2+, and Ca2+ are indicated at the top. Five microliters (OD600 0.2) of 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3–4 days.

(B) Growth curves of yeast cells expressing pYES2 and ΔN25PML3 were plotted from OD600 values. Growth of yeast cells in liquid cultures containing 0, 1, or 2 mM EGTA was monitored every 3 h from 18 to 51 h. Data are means ± SD. n = 3.

(C) ICP-MS analysis of Mn content in Δsmf1 cells expressing pYES2 (Δsmf1 + pYES2) and ΔN25PML3 (Δsmf1 + ΔN25PML3) cultured in Mn2+-deficient or Mn2+-sufficient liquid SC-U medium (OD600 1.0). Data are means ± SD. n = 3. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the negative control (Δsmf1 + pYES2) (Student's t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

Arabidopsis pml3 seedlings are defective under Mn-limited conditions

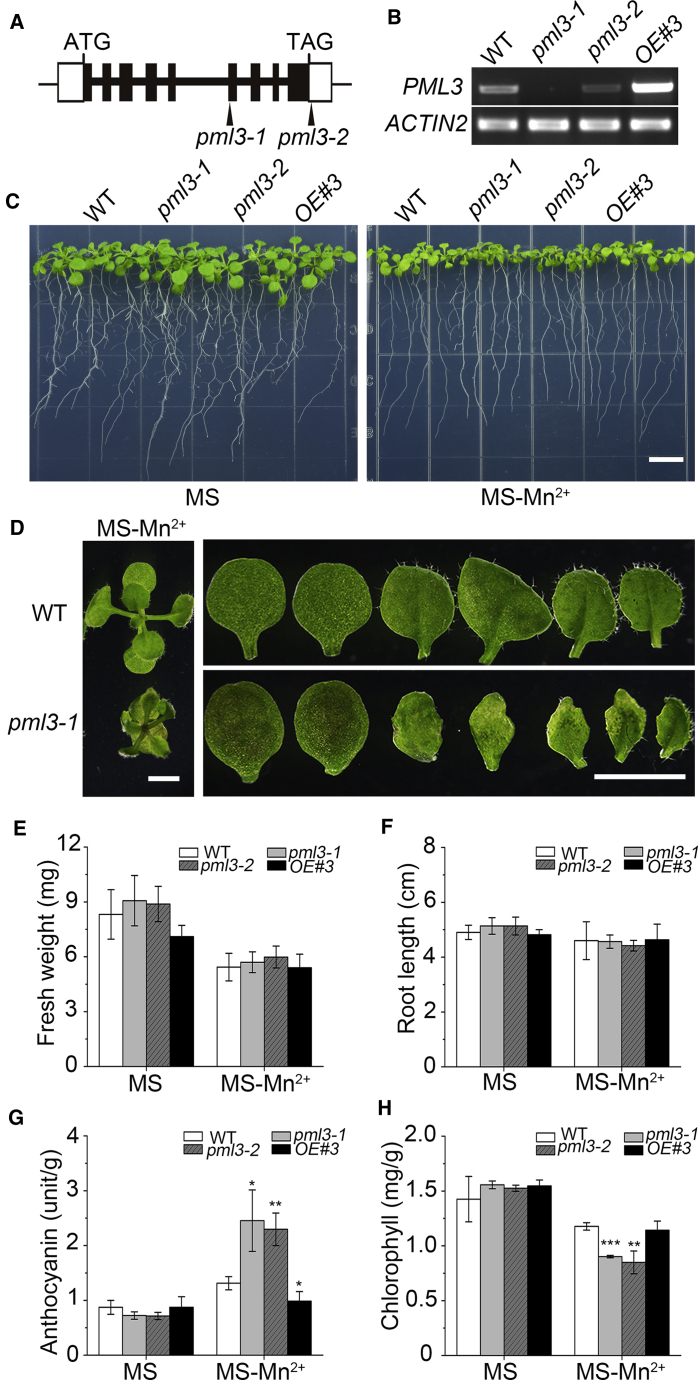

To analyze the function of PML3 protein in planta, we analyzed two transfer-DNA (T-DNA) insertional alleles of PML3 (AT5G36290) named pml3-1 (GABI_027F07) and pml3-2 (SALK_097998). Transcript analysis using RT-PCR showed that pml3-1 was a knockout allele and pml3-2 was a knockdown allele (Figure 4A and 4B). Both pml3 mutants showed no visible differences compared with the WT on the MS medium. When they were grown on MS medium without Mn for 11 days, both pml3 mutant seedlings exhibited curled and brownish leaves (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 3). However, the WT and the pml3-1 mutant did not differ in Mn content under either Mn-sufficient or Mn-deficient conditions (Supplemental Table 1), suggesting that low-Mn conditions may have altered the subcellular distribution of Mn. Under deficiency of other divalent cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Fe2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, or Co2+), the mutant plants were similar to the WT (Supplemental Figure 4). On Mn-deficient medium, pml3 mutant plants displayed greater anthocyanin accumulation and lower chlorophyll content, but the fresh weight and root length of the mutants were minimally affected at this stage (Figure 4E–4H). The phenotype of the pml3 mutants induced by Mn deficiency is Mn dose–dependent (Supplemental Figure 5). Intriguingly, the growth defects in pml3 mutants were irreversible, as transfer of the seedlings to Mn-replete medium did not restore the leaf phenotype to normal. To confirm that the phenotype of pml3 was due to mutation of the PML3 gene, we ligated 35S::PML3-GFP and the PML3 genomic fragment into the pCAMBIA1300 vector and introduced them into the pml3-1 mutant plants by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Transgenic plants harboring either the overexpression construct (OE#3) or the genomic fragment (COM) displayed normal growth like that of WT plants under Mn-deficient conditions (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Mutation of PML3 influences leaf growth under Mn deficiency.

(A)Arabidopsis PML3 gene structure and locations of the T-DNA insertion sites in pml3-1 and pml3-2 lines. The PML3 gene contains nine exons (black boxes) and eight introns (bold black lines). The 5′ and 3′ UTRs are indicated by open boxes. ATG, translation start codon; TAG, stop codon.

(B) RT–PCR analysis of WT, pml3-1, pml3-2, and pml3-1 transformed with PML3 CDS fragment driven by the 35S promoter (OE#3). ACTIN2 was used as a loading control.

(C) Phenotypes of WT, pml3-1, pml3-2, and OE#3 plants grown on MS medium with or without Mn2+ for 2 weeks under 90 μmol/m2/s light with a long-day cycle (16 h light/8 h dark). Scale bar, 1 cm.

(D) The enlargement and detached leaves of WT and pml3-1 plants in MS medium without Mn2+ described in (C). Scale bar, 2 mm.

(E–H) (E) Fresh weight, (F) root length, (G) anthocyanin content, and (H) chlorophyll content of 2-week-old plants shown in (C). Data are means ± SD. n = 6 for (E) and (F), and n = 3 for (G) and (H). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with WT (Student's t-test, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

To analyze the phenotype of adult plants, 2-week-old WT and pml3-1 mutant seedlings grown in Mn-sufficient hydroponic culture were transferred to hydroponic culture lacking Mn. When the plants were cultured under Mn-deficient hydroponic conditions for 10 days, the young leaves of mutant plants that emerged after the transfer shrank and curled, whereas older leaves were not affected (Supplemental Figure 7A). We measured chlorophyll and anthocyanin contents in young and old leaves separately and found increased anthocyanin content and decreased chlorophyll content in young leaves of the mutant (Supplemental Figure 7B and 7C). Trypan blue staining revealed that the young leaves of pml3-1 showed pronounced cell death under Mn-limited conditions (Supplemental Figure 7D). This raised the possibility that Mn remobilization into young leaves may be disrupted in the mutant, but inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) results showed that Mn content did not differ significantly between the WT and the pml3-1 mutant (Supplemental Table 2). Taken together, the data from plate culture and hydroponic culture suggested that PML3 plays a role in the early growth and development of leaves.

The PML3 gene is essential for pollen tube growth

Although low Mn in plate and hydroponic culture resulted in leaf growth abnormality in the pml3 mutant plants, the WT and the two pml3 mutants did not show significant differences during vegetative growth in the soil (Supplemental Figure 8A). However, in the reproductive stage, the siliques of both pml3 mutants were drastically shorter than those of the WT, leading to a severe reduction in seed yield (Figure 5A–5D, Supplemental Figure 8B–8D).

Figure 5.

Mutation of PML3 reduced the seed set.

(A) Representative siliques from WT, pml3-1, pml3-2, and OE#3 plants. Scale bar, 5 mm.

(B) Seed development in the siliques of WT and pml3-1 plants. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(C and D) (C) Silique length and (D) seed number of WT, pml3-1, pml3-2, and OE#3 plants. n = 12 for (C), and n = 6 for (D).

(E) Siliques generated by crossing WT and the pml3-1 mutant. Scale bar, 5 mm.

(F) Seed development in siliques of reciprocally crossed plants. Scale bar, 2 mm.

(G and H) (G) Silique length and (H) seed number of reciprocally crossed plants. n = 8 for (G), and n = 7 for (H). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with WT (Student's t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

To understand the role of PML3 in reproductive processes, we first analyzed T2 progeny segregation of the self-pollinated heterozygous pml3 mutant by PCR-based genotyping. The result revealed a WT:heterozygous:homozygous ratio of 149:200:19 in the T2 progeny (n = 368), consistent with a gametophytic defect associated with the mutant allele (Supplemental Table 3). To investigate whether the mutation affected the male or female gametophyte, we conducted reciprocal crosses between the WT and the pml3-1 mutant. When the pml3-1 mutant was used as the female parent and the WT was used as a pollen donor, no seed set defect was observed in the progeny. However, when pml3-1 was used as the pollen donor to pollinate WT plants, the siliques were significantly shorter, and seed set was reduced (Figure 5E–5H). The transmission efficiency through the male gametophyte was only 3% in pml3+/− mutants, indicating that mutation of the PML3 gene affected male gametophyte development (Supplemental Table 4). Hence, the seed set defects in the pml3-1 mutant were specifically associated with the male gametophyte.

To address the cause of the pollen-specific transmission defect in the pml3 mutant, we analyzed the morphology and vitality of the pollen grains. Pollen grains from the pml3-1 mutant were viable and indistinguishable from those of the WT (Supplemental Figure 9). We examined pollen germination efficiency and pollen tube growth in vitro and found that the germination rate of the pml3 mutant was significantly lower than that of the WT, and a large proportion of pollen tubes in the mutant ruptured immediately after germination. In addition, germinated pml3 pollen tubes exhibited abnormal morphological changes such as branching and swelling (Figure 6A, 6B, and 6E). The pollen tubes of pml3 mutants were also dramatically shorter and wider than the WT pollen tubes (Figure 6C and 6D). Time-lapse observations showed that the pollen tube growth rate of pml3 was much slower than that of the WT (Figure 6F and 6G). The results of the in vitro pollen tube growth assay were confirmed by a pollination assay in which we pollinated WT pistils with either WT or mutant pollen grains. Following pollination, we monitored pollen tube elongation in the stigma over a 24-h time course using aniline blue staining. We found that the pml3 pollen tubes elongated significantly more slowly than the WT (Figure 6H and 6I). Together, these results suggested that the seed set defect in pml3 resulted from defects in pollen tube growth.

Figure 6.

Mutation of PML3 impaired pollen tube growth in vitro and in vivo.

(A)In vitro pollen germination of WT, pml3-1, pml3-2, and OE#3 plants. Black arrows and inset photos indicate burst pollen tubes. Scale bars: 200 μm (A) and 20 μm (inset).

(B–D) (B) A typical WT pollen tube germinated for 6 and 24 h. The pml3-1 pollen tubes show relatively normal morphology (top), swelling (middle), and branching (bottom). Scale bar: 50 μm. The pollen tube length (C) and width (D) described in (A). Data are means ± SD. n = 30 for (C), and n = 24–33 for (D). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with WT (Student's t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

(E and F) (E) Percentages of burst pollen tubes of pml3 mutants. n = 213–326. (F) Time series of pollen tube growth. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(G)In vitro pollen tube growth rate of WT and pml3-1. Data are means ± SD. n = 20 for WT, and n = 30 for pml3-1. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with WT (Student's t-test, ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

(H and I) (H) Semi-in vitro and (I)in vivo germinated pollen tubes of pml3-1 mutants are shorter than those of WT. Scale bars: 1 mm (H) and 200 μm (I).

Pectin deposition in the pollen tube cell wall is altered in the pml3 mutant

The Golgi localization of PML3 suggested a potential function of this Mn transporter in Golgi-mediated processes such as cell wall biosynthesis and the secretory pathway. Rapid pollen tube growth requires efficient biosynthesis and deposition of cell-wall components, including pectin and hemicellulose. We therefore hypothesized that pollen tube defects in the pml3 mutant may be related to defects in the cell wall. Using ruthenium red, we stained pectin in the pollen tube. As expected, pectin was strongly labeled in the tip region of the WT pollen tubes for rapid tip growth. By contrast, ruthenium red staining in the pml3 pollen tubes was diminished in the tip region, suggesting reduced pectin content in the elongating pollen tubes (Figure 7A). Homogalacturonans (HGs) are the most abundant pectin polymers in the pollen tube, and the degree of HG esterification in a gradient distribution is important for rapid tip growth. To gain insight into HG alterations in pml3 pollen tubes, we performed an immunostaining assay to monitor the distribution of esterified and de-esterified HGs using JIM7 and JIM5 monoclonal antibodies, respectively. In the WT, as previously reported (Dardelle et al., 2010; Chebli et al., 2012), esterified HGs labeled by JIM7 were confined mostly to the apical region of the pollen tubes, whereas de-esterified HGs stained with JIM5 were enriched in the shaft away from the tip (Figure 7D and 7E). The JIM7-labeled esterified HG signal in the pml3 pollen tubes was indistinguishable from that in the WT. However, the JIM5-labeled de-esterified pectin signal was much stronger at the tip region in pml3 pollen tubes than in the WT (Figure 7D, 7E, 7G, and 7H). Arabinogalactan proteins, which are vital to plant sexual reproduction, exhibited similar patterns in WT and pml3 pollen tubes, as shown by LM2 antibody labeling (Figure 7F). In addition, callose (stained by aniline blue) and cellulose (stained by calcofluor white) were also indistinguishable between the WT and the pml3 mutant (Figure 7B and 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that pollen tube defects in the pml3 mutant may result from altered composition of the cell wall, especially the excessive deposition of de-esterified pectin at the tip region, which may hinder normal tip growth of the pollen tube.

Figure 7.

The cell wall components in the pollen tube of the pml3 mutant are altered.

Chemical staining using (A) ruthenium red (pectin), (B) aniline blue (callose), and (C) calcofluor white (cellulose and callose) and immunolabeling using (D) JIM5 (de-esterified homogalacturonan), (E) JIM7 (esterified homogalacturonan), and (F) LM2 (arabinogalactan protein) antibodies to analyze the cell wall components in WT and pml3-1 pollen tubes. pml3-1 pollen tubes show relatively normal morphology (middle) and a swelling tip (right). Scale bars: 20 μm. Quantification of fluorescent signal intensity from the tip to the shaft of the pollen tube using (G) JIM5 and (H) JIM7 antibody, respectively, is shown. Data are means ± SD. n = 20 for each genotype.

Discussion

The plant Golgi apparatus plays a central role in intracellular trafficking and functions as the biochemical factory for protein modification and cell wall polysaccharide synthesis. Numerous enzymes in the Golgi along the cis–trans axis guarantee that diverse metabolic reactions take place in an orderly fashion. Many Golgi enzymes require Mn2+ as a cofactor. Therefore, Mn partitioning in the Golgi must be fine-tuned by the coordinated action of multiple Mn transporters across the Golgi membranes. In this study, we identified PML3 as a cis-Golgi-localized Mn transporter that contributes to normal cell wall biosynthesis, especially in rapidly growing cells, including those of young leaves and pollen tubes.

Several lines of evidence support the identification of PML3 as a Golgi-localized Mn transporter. First, PML3 belongs to the evolutionarily conserved UPF0016 family, members of which are characterized as Mn transporters in diverse species (Fisher et al., 2016; Potelle et al., 2016; Schneider et al., 2016; Brandenburg et al., 2017; Gandini et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Thines et al., 2020) (Supplemental Figure 1). We performed a yeast complementation assay that confirmed PML3 as a Mn transporter (Figure 3). Second, the PML3 protein was predicted to contain a signal peptide for the secretory pathway in the N terminus and was shown to be enriched in the Golgi membrane fraction in a proteomics analysis (Parsons et al., 2012). Using organelle markers, we further confirmed that a PML3–GFP fusion was localized in the cis-Golgi (Figure 1). Third, the genetic analysis of PML3 function using Arabidopsis pml3 mutant plants showed that the lack of PML3 function was associated with leaf growth defects only under Mn-limited conditions in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 4, Supplemental Figures 3 and 5).

Several Mn transporters have been characterized in the Golgi apparatus. A P2A-type ATPase, ECA3, functions as a Mn2+ pump for Mn flux into the Golgi. Under Mn-limited conditions, eca3 mutants showed a reduction in shoot and root growth (Mills et al., 2008). NRAMP2 is a Mn transporter located in the TGN. The nramp2 mutant showed chlorotic leaves and decreased activity of photosystem II under Mn-deficient conditions. These phenotypes were associated with decreased Mn content in vacuoles and chloroplasts, suggesting that NRAMP2 may play a role in recycling Mn from the TGN to the vacuole and ultimately in supplying Mn to the chloroplasts (Alejandro et al., 2017). Arabidopsis MTP11, which appeared to be localized in the Golgi/PVC, supports Mn tolerance when plants face high concentrations of Mn. Arabidopsis mtp11 mutants are hypersensitive, but plants that overexpress MTP11 are more tolerant to elevated levels of Mn2+. The mtp11 mutants have higher Mn concentrations in shoots and roots, suggesting that Golgi-located MTP11 may play a role in excluding excess Mn through vesicular trafficking and exocytosis (Delhaize et al., 2007; Peiter et al., 2007). Unlike most of the Mn-related mutants mentioned above, pml3 seedlings showed curled, brownish leaves and increased anthocyanin accumulation under Mn-deficient conditions. These phenotypes were preferentially exhibited in young leaves (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 7). In addition, pml3 pollen tubes showed aberrant bursting and slower elongation. The fact that a lack of PML3 caused strong growth defects in fast-growing tissues such as young leaves and pollen tubes revealed novel functions for PML3, distinguishing it from previously reported Mn transporters. Such specific functions may be attributed to the distinct tissue-specific expression pattern and subcellular localization of these Mn transporters.

Pollen tube elongation is a typical tip growth process that requires rapid synthesis and deposition of cell wall components to different parts of the tube structure in a highly regulated manner. In particular, pectin polymers are enriched in the growing pollen tube to confer a variety of mechanical properties that promote rapid remodeling of the cell wall. HGs, the most abundant pectin polysaccharides in the pollen tube cell wall, are synthesized in the Golgi and secreted in a highly esterified form to the tip region of the pollen tube. The highly esterified HGs are then de-esterified by pectin methyl-esterase in the subapical region. The highly esterified HG in the tip region provides this zone with elastic properties that permit directional expansion, whereas the de-esterified HG associated with the shank region confers rigidity to support rapid tip growth. Our immunofluorescence assay indicated that de-esterified HGs were abnormally increased in the tip region of the pml3 mutant pollen tube. This may have increased cell wall rigidity in the tip region, hindering tip growth in the pml3 mutant pollen tube (Figure 7). By contrast, the contents of other components (such as arabinogalactan proteins, callose, and cellulose) in the pollen tube cell wall of pml3 appeared to be comparable to those in the WT (Figure 7). Hence, we speculated that the abnormal accumulation of de-esterified HGs in the tip region of the pollen tube cell wall blocks the polarized tip growth process (Figures 6 and 7).

The Golgi apparatus is the hub for the biosynthesis of many cell wall polysaccharides, including hemicelluloses, pectin, and hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins. The synthesis of HGs in the Golgi is catalyzed by the galacturonosyltransferases (GAUTs), whose activity is promoted by Mn2+ in vitro (Sterling et al., 2001, 2006). Two GAUTs highly expressed in pollen, GAUT13 and GAUT14, have been shown to play essential roles in pollen tube growth because a gaut13/gaut14 double mutant exhibited pollen tube growth defects, probably due to the alteration of pectin distribution (Wang et al., 2013). A recent study showed that three more GAUTs, GAUT5, GAUT6, and GAUT7, were required for pollen tube germination and elongation, and pectin deposition was also altered in the pollen tubes of double or triple mutants (Lund et al., 2020). In addition, the Golgi apparatus is an important compartment for glycosylation. Interestingly, the homologs of PML3, TMEM165 in human and GDT1 in yeast, are localized in the Golgi and affect the glycosylation process (Foulquier et al., 2012; Potelle et al., 2016). Indeed, many enzymes involved in glycosylation, such as hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferases (HPAT), require Mn2+ as a cofactor (Ogawa-Ohnishi et al., 2013). It was reported that de-esterified HGs were aberrantly enriched in the tip region of pollen tubes in hpat1/hpat3 double mutants (Beuder et al., 2020), as shown here in the pml3 mutant. We therefore hypothesize that PML3, as a cis-Golgi-localized Mn transporter, plays a critical role in Mn homeostasis in the Golgi lumen, thereby affecting the activity of Mn-dependent enzymes involved in cell wall biosynthesis and/or glycosylation processes. Such processes are particularly important for the remodeling of cell wall structure and dynamics during the rapid growth of tissues/cells, including young leaves and pollen tubes. Future studies should be directed at identifying those enzymes supported by Golgi-localized Mn transporters such as PML3.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana WT (ecotype Columbia-0) and the T-DNA insertion lines pml3-1 (GABI_027F07) and pml3-2 (SALK_097998) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. Homozygous individuals were screened by PCR using the primers listed in Supplemental Table 5. Surface-sterilized Arabidopsis seeds were planted on MS medium containing 1% (w/v) sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agar (Caisson Labs) with or without Mn2+ (pH 5.8). After stratification at 4°C for 2 days, the plants were grown in a growth chamber. For soil culture, 10-day-old seedlings germinated on MS were transferred to nutrient-rich soil (Pindstrup Mosebrug, Denmark) and then grown in the greenhouse. The conditions in the growth chamber and greenhouse were normal light conditions (90 μmol/m2/s) with a long-day cycle (16 h light/8 h dark) at 22°C.

RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). The RT-PCR analysis of gene expression was followed by 25 or 30 cycles of PCR. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) on a CFX Connect real-time system (Bio-Rad). Target quantifications were performed with specific primer pairs designed using the NCBI Primer designing tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). ACTIN2 was used as an internal reference gene for both RT-PCR and quantitative real-time PCR analysis. All primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 5.

Vector construction and plant transformation

For genetic complementation, the PML3 CDS fragment (882 bp) and the full-length genomic DNA of PML3 (a 4319-bp fragment containing a 2000-bp promoter, 1996-bp exon and intron sequence, and 323-bp downstream sequence) were amplified and cloned into the binary vectors pCAMBIA-1302 and pCAMBIA-1300, respectively. To generate the PML3 promoter GUS construct (PML3pro::GUS), the 2000-bp promoter region upstream of the initial ATG codon was amplified and cloned into the modified pCAMBIA-1300 binary vector with the GUS reporter gene. These constructs were introduced into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 strain for transformation into pml3-1 and WT plants by the floral dip method. Transgenic plants were screened on half-strength MS medium containing 25 μg/ml hygromycin. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 5.

Histochemical GUS analysis

GUS staining was performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2018). The samples from the T2 independent transgenic plants were fixed in 90% ice-cold acetone for 30 min and washed with staining buffer (0.5 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 0.5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, and 100 mM sodium phosphate). The samples were incubated in staining buffer containing 1 mM X-Gluc for 12 h at 37°C, then washed with 70% ethanol for destaining. The expression patterns were recorded with a microscope (SZX16, Olympus).

Subcellular localization of PML3

For subcellular localization analysis, the CDS of PML3 was cloned into the pEZS-NL-GFP vector. Arabidopsis protoplasts were digested and transformed with the fusion constructs via polyethylene glycol-mediated transfection as previously described (Zhang et al., 2018). Images were obtained by laser confocal fluorescence microscopy (Leica TCS SP8-MaiTai MP). The fluorescent signals of GFP and RFP were imaged by excitation at 488 nm and 561 nm, respectively. The PSC Colocalization plugin of ImageJ was used for colocalization analysis.

Measurement of metal contents by ICP-MS

WT and pml3-1 plants were grown on MS solid medium and hydroponic culture (one-sixth strength MS) with or without Mn2+, and the tissues were collected and dried at 70°C for 72 h. The samples were then digested with concentrated HNO3 (ultrapure) in a digester (DigiBlock ED16, LabTech). Ion concentrations were measured by ICP-MS (NexION 300, PerkinElmer).

Heterologous expression of PML3 in yeast

For complementation of the yeast mutants, the full-length CDS and a truncated version of PML3 (without the first 25 amino acids corresponding to the SP region) were separately cloned into the pYES2 vector to express GFP fusion proteins. The pYES2 empty vector and recombinant plasmids were introduced into the yeast mutant strain as described in the Yeast Protocols Handbook (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). The yeast strain used in this study was the Mn2+-uptake-deficient mutant Δsmf1 (MATa his2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 YOL122c::KanMX4). The cells transformed with indicated constructs were grown on synthetic medium containing amino acids without uracil. Complementation of the Δsmf1 phenotype was tested on a synthetic medium containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% galactose, 0.2% appropriate amino acids (uracil omitted), and 2% agar; pH was buffered at 6.0 with 50 mM MES supplemented with 0, 10, or 20 mM EGTA. Yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation at 700 g for 5 min and washed twice with sterile water. The cells were resuspended and adjusted to OD600 0.2, and 5 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto the plates as indicated above. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3–5 days before being photographed.

The yeast cells with different vectors were precultured overnight to OD600 1.0, harvested by centrifugation at 700 g for 5 min, and washed twice with sterile water. The samples were dried at 70°C for 72 h and then digested with concentrated HNO3 (ultrapure) in a digester (DigiBlock ED16, LabTech). Ion concentration was measured by ICP-MS (NexION 300, PerkinElmer).

Anthocyanin and chlorophyll content assays

The anthocyanin content was detected using the method described previously (Liu et al., 2015). In brief, a 20-mg sample was ground in liquid nitrogen and incubated in 1 ml 1% HCl in methanol (vol/vol) in the dark at 4°C with gentle shaking overnight. The tubes were centrifuged at 12 000 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The absorbance of each supernatant was measured spectrophotometrically at 530 nm and 657 nm, and anthocyanin content was calculated as A530 − (0.25 × A657)/FW. For chlorophyll content, 20 mg of leaves were harvested and ground in 1 ml 80% acetone and then placed in the dark at 4°C for 30 min. The tubes were centrifuged at 12 000 g for 5 min, and the supernatants were used for spectrophotometric measurements (Biomate 3S, Thermo Scientific) at 645 nm and 663 nm. The chlorophyll content was calculated as (20.2 × A645 + 8.02 × A663)/FW.

Pollen tube growth analysis

For pollen tube growth in vitro, pollen grains were harvested from freshly opened flowers and germinated in pollen germination medium (PGM) as described previously (Wang and Jiang, 2011). The length and width of pollen tube were measured using ImageJ software. To measure pollen tube growth rates, pollen grains were pollinated on slides, which were placed in a Petri dish containing a damp towel to maintain high humidity. After 3 h of germination, the Petri dish was directly imaged for 30 min at 5-min intervals using a BX53 microscope (Olympus). The growth rate was calculated by measuring the difference in pollen tube length between frames using ImageJ.

For the semi-in vitro assay, the pollinated pistil was cut at the junction of the carpel valve and the style, placed horizontally on solid PGM, and cultured for 6–24 h.

To assess pollen tube growth in vivo (Ge et al., 2017), the pollinated pistils were fixed with ethanol/acetic acid (3/1) for 6 or 24 h, and an ethanol gradient of 70% (v/v), 50% (v/v), and 30% (v/v) and distilled water was used to rehydrate the pistils. The pistils were incubated in 8 M NaOH overnight at 22°C to soften and then washed at least three times with distilled water. The samples were stained with aniline blue (0.1% [w/v] aniline blue in 100 mM phosphate buffer [pH 8.0]) for more than 2 h in the dark. Images were obtained using a laser confocal fluorescence microscope (Leica TCS SP8-MaiTai MP) with 405 nm excitation and 420–480 nm emission.

Immunolabeling and cytochemical staining

Immunolabeling of pollen tube cell wall epitopes was performed as described previously with some modifications (Tan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Pollen tubes were adhered to poly-L-lysine-covered glass slides after germination in liquid PGM for 4 h. Pollen tubes were fixed in 4% (w/v) polyformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature and washed with 0.1 M PBS buffer three times for 5 min each. The samples were blocked with 3% BSA (diluted in 0.1 M PBS buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with 0.1 M PBS buffer for 5 min each, the pollen tubes were incubated with the JIM5, JIM7, and LM2 antibodies (Kerafast, 1:10 diluted in PBS buffer containing 0.1% BSA) at 4°C overnight. The pollen tubes were washed three times with 0.1 M PBS buffer for 5 min each, then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Sangon, 1:100 diluted in PBS buffer containing 0.1% BSA) for 1 h in the dark. The samples were washed with 0.1 M PBS three times and then observed by laser confocal fluorescence microscopy (Leica TCS SP8-MaiTai MP). Photographs were taken using 488 nm excitation and 495–600 nm emission, and the laser intensity and gain were consistent for different experiments.

For cytochemical staining, pollen tubes that had germinated in liquid PGM for 4 h were fixed in 4% (w/v) polyformaldehyde for 1 h and washed with 0.1 M PBS buffer three times. Aniline blue and calcofluor white were used at final concentrations of 0.1% (w/v) and 0.01% (w/v), respectively. A laser confocal fluorescence microscope was used to take photographs with 405 nm excitation and 420–480 nm emission. For ruthenium red (0.01%, w/v) staining, pollen tubes germinated in liquid PGM were stained without fixation and observed with a light microscope (BX53, Olympus).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31900220 to C.Z.) and the National Science Foundation (1714795 to S.L.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Fangjie Zhao for advice on ICP-MS analysis. No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

B.Z. and S.L. designed the research. B.Z., C.Z., and C.L. carried out the experiments. B.Z., C.Z., and S.L. analyzed the data. A.F. provided technical assistance. B.Z., C.Z., and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

Published: March 18, 2021

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Aigen Fu, Email: aigenfu@nwu.edu.cn.

Sheng Luan, Email: sluan@berkeley.edu.

Accession number

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database under the following accession number: PML3 (AT5G36290).

Supplemental information

References

- Alejandro S., Cailliatte R., Alcon C., Dirick L., Domergue F., Correia D., Castaings L., Briat J.F., Mari S., Curie C. Intracellular distribution of manganese by the trans-Golgi network transporter NRAMP2 is critical for photosynthesis and cellular redox homeostasis. Plant Cell. 2017;29:3068–3084. doi: 10.1105/tpc.17.00578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alejandro S., Holler S., Meier B., Peiter E. Manganese in plants: from acquisition to subcellular allocation. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:300. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuder S., Dorchak A., Bhide A., Rune Moeller S., Petersen B.L., MacAlister C.A. Exocyst mutants suppress pollen tube growth and cell wall structural defects of hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferase mutants. Plant J. 2020;103:1399–1419. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg F., Schoffman H., Kurz S., Kramer U., Keren N., Weber A.P., Eisenhut M. The Synechocystis manganese exporter Mnx is essential for manganese homeostasis in Cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:1798–1810. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley M., Brown P., Cakmak I., Rengel Z., Zhao F. Third Edition. Academic Press; San Diego: 2012. Chapter 7 - Function of Nutrients: Micronutrients. Marschner's Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; pp. 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cailliatte R., Schikora A., Briat J.F., Mari S., Curie C. High-affinity manganese uptake by the metal transporter NRAMP1 is essential for Arabidopsis growth in low manganese conditions. Plant Cell. 2010;22:904–917. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaings L., Caquot A., Loubet S., Curie C. The high-affinity metal transporters NRAMP1 and IRT1 Team up to take up iron under sufficient metal provision. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37222. doi: 10.1038/srep37222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebli Y., Kaneda M., Zerzour R., Geitmann A. The cell wall of the Arabidopsis pollen tube--spatial distribution, recycling, and network formation of polysaccharides. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:1940–1955. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.199729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardelle F., Lehner A., Ramdani Y., Bardor M., Lerouge P., Driouich A., Mollet J.C. Biochemical and immunocytological characterizations of Arabidopsis pollen tube cell wall. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1563–1576. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhaize E., Gruber B.D., Pittman J.K., White R.G., Leung H., Miao Y., Jiang L., Ryan P.R., Richardson A.E. A role for the AtMTP11 gene of Arabidopsis in manganese transport and tolerance. Plant J. 2007;51:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaegd D., Foulquier F., Colinet A.S., Gremillon L., Legrand D., Mariot P., Peiter E., Van Schaftingen E., Matthijs G., Morsomme P. Newly characterized Golgi-localized family of proteins is involved in calcium and pH homeostasis in yeast and human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:6859–6864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219871110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhuta M., Hoecker N., Schmidt S.B., Basgaran R.M., Flachbart S., Jahns P., Eser T., Geimer S., Husted S., Weber A.P.M. The plastid envelope CHLOROPLAST MANGANESE TRANSPORTER1 is essential for manganese homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:955–969. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu S., Meier B., von Wiren N., Peiter E. The vacuolar manganese transporter MTP8 determines tolerance to iron deficiency-induced Chlorosis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:1030–1045. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C.R., Wyckoff E.E., Peng E.D., Payne S.M. Identification and characterization of a putative manganese export protein in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2016;198:2810–2817. doi: 10.1128/JB.00215-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulquier F., Amyere M., Jaeken J., Zeevaert R., Schollen E., Race V., Bammens R., Morelle W., Rosnoblet C., Legrand D. TMEM165 deficiency causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandini C., Schmidt S.B., Husted S., Schneider A., Leister D. The transporter SynPAM71 is located in the plasma membrane and thylakoids, and mediates manganese tolerance in Synechocystis PCC6803. New Phytol. 2017;215:256–268. doi: 10.1111/nph.14526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Xie W., Yang C., Xu J., Li J., Wang H., Chen X., Huang C.F. NRAMP2, a trans-Golgi network-localized manganese transporter, is required for Arabidopsis root growth under manganese deficiency. New Phytol. 2018;217:179–193. doi: 10.1111/nph.14783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Z., Bergonci T., Zhao Y., Zou Y., Du S., Liu M.-C., Luo X., Ruan H., García-Valencia L.E., Zhong S. Arabidopsis pollen tube integrity and sperm release are regulated by RALF-mediated signaling. Science. 2017;358:1596–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker N., Honke A., Frey K., Leister D., Schneider A. Homologous proteins of the manganese transporter PAM71 are localized in the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum. Plants (Basel) 2020;9:239. doi: 10.3390/plants9020239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V., Lelievre F., Bolte S., Hames C., Alcon C., Neumann D., Vansuyt G., Curie C., Schroder A., Kramer U. Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J. 2005;24:4041–4051. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar V., Ramos M.S., Lelievre F., Barbier-Brygoo H., Krieger-Liszkay A., Kramer U., Thomine S. Export of vacuolar manganese by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is required for optimal photosynthesis and growth under manganese deficiency. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1986–1999. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.150946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Chanroj S., Wu Z., Romanowsky S.M., Harper J.F., Sze H. A distinct endosomal Ca2+/Mn2+ pump affects root growth through the secretory process. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:1675–1689. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yang L., Luan M., Wang Y., Zhang C., Zhang B., Shi J., Zhao F.G., Lan W., Luan S. A vacuolar phosphate transporter essential for phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:E6571–E6578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514598112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C.H., Stenbaek A., Atmodjo M.A., Rasmussen R.E., Moller I.E., Erstad S.M., Biswal A.K., Mohnen D., Mravec J., Sakuragi Y. Pectin synthesis and pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis involves three GAUT1 Golgi-anchoring proteins: GAUT5, GAUT6, and GAUT7. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:585774. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.585774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary V., Schnell Ramos M., Gillet C., Socha A.L., Giraudat J., Agorio A., Merlot S., Clairet C., Kim S.A., Punshon T. Bypassing iron storage in endodermal vacuoles rescues the iron mobilization defect in the natural resistance associated-macrophage protein3 natural resistance associated-macrophage protein4 double mutant. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:748–759. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R.F., Doherty M.L., Lopez-Marques R.L., Weimar T., Dupree P., Palmgren M.G., Pittman J.K., Williams L.E. ECA3, a Golgi-localized P2A-type ATPase, plays a crucial role in manganese nutrition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:116–128. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.110817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner M.J., Seamon J., Craft E., Kochian L.V. Transport properties of members of the ZIP family in plants and their role in Zn and Mn homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:369–381. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa-Ohnishi M., Matsushita W., Matsubayashi Y. Identification of three hydroxyproline O-arabinosyltransferases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:726–730. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons H.T., Christiansen K., Knierim B., Carroll A., Ito J., Batth T.S., Smith-Moritz A.M., Morrison S., McInerney P., Hadi M.Z. Isolation and proteomic characterization of the Arabidopsis Golgi defines functional and novel components involved in plant cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:12–26. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.193151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiter E., Montanini B., Gobert A., Pedas P., Husted S., Maathuis F.J., Blaudez D., Chalot M., Sanders D. A secretory pathway-localized cation diffusion facilitator confers plant manganese tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:8532–8537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609507104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potelle S., Dulary E., Climer L., Duvet S., Morelle W., Vicogne D., Lebredonchel E., Houdou M., Spriet C., Krzewinski-Recchi M.A. Manganese-induced turnover of TMEM165. Biochem. J. 2017;474:1481–1493. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potelle S., Morelle W., Dulary E., Duvet S., Vicogne D., Spriet C., Krzewinski-Recchi M.A., Morsomme P., Jaeken J., Matthijs G. Glycosylation abnormalities in Gdt1p/TMEM165 deficient cells result from a defect in Golgi manganese homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:1489–1500. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A., Steinberger I., Herdean A., Gandini C., Eisenhut M., Kurz S., Morper A., Hoecker N., Ruhle T., Labs M. The evolutionarily conserved protein PHOTOSYNTHESIS AFFECTED MUTANT71 is required for efficient manganese uptake at the thylakoid membrane in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2016;28:892–910. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.R. The structure of photosystem II and the mechanism of water oxidation in photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:23–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socha A.L., Guerinot M.L. Mn-euvering manganese: the role of transporter gene family members in manganese uptake and mobilization in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:106. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling J.D., Atmodjo M.A., Inwood S.E., Kumar Kolli V.S., Quigley H.F., Hahn M.G., Mohnen D. Functional identification of an Arabidopsis pectin biosynthetic homogalacturonan galacturonosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:5236–5241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600120103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling J.D., Quigley H.F., Orellana A., Mohnen D. The catalytic site of the pectin biosynthetic enzyme alpha-1,4-galacturonosyltransferase is located in the lumen of the Golgi. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:360–371. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X., Cao K., Liu F., Li Y., Li P., Gao C., Ding Y., Lan Z., Shi Z., Rui Q. Arabidopsis COG complex subunits COG3 and COG8 modulate Golgi morphology, vesicle trafficking homeostasis and are essential for pollen tube growth. Plos Genet. 2016;12:e1006140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thines L., Stribny J., Morsomme P. From the Uncharacterized Protein Family 0016 to the GDT1 family: molecular insights into a newly-characterized family of cation secondary transporters. Microb. Cell. 2020;7:202–214. doi: 10.15698/mic2020.08.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomine S., Lelievre F., Debarbieux E., Schroeder J.I., Barbier-Brygoo H. AtNRAMP3, a multispecific vacuolar metal transporter involved in plant responses to iron deficiency. Plant J. 2003;34:685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Jiang L. Transient expression and analysis of fluorescent reporter proteins in plant pollen tubes. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang W., Wang Y.Q., Liu Y.Y., Wang J.X., Zhang X.Q., Ye D., Chen L.Q. Arabidopsis galacturonosyltransferase (GAUT) 13 and GAUT14 have redundant functions in pollen tube growth. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:1131–1148. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang K., Yin G., Liu X., Liu M., Cao N., Duan Y., Gao H., Wang W., Ge W. Pollen-expressed leucine-rich repeat extensins are essential for pollen germination and growth. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1993–2006. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Liang F., Hong B., Young J.C., Sussman M.R., Harper J.F., Sze H. An endoplasmic reticulum-bound Ca(2+)/Mn(2+) pump, ECA1, supports plant growth and confers tolerance to Mn(2+) stress. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:128–137. doi: 10.1104/pp.004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Zhang C., Liu C., Jing Y., Wang Y., Jin L., Yang L., Fu A., Shi J., Zhao F. Inner envelope CHLOROPLAST MANGANESE TRANSPORTER 1 supports manganese homeostasis and phototrophic growth in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2018;11:943–954. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.