Abstract

When plants are exposed to hypoxic conditions, the level of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in plant tissues increases by several orders of magnitude. The physiological rationale behind this elevation remains largely unanswered. By combining genetic and electrophysiological approach, in this work we show that hypoxia-induced increase in GABA content is essential for restoration of membrane potential and preventing ROS-induced disturbance to cytosolic K+ homeostasis and Ca2+ signaling. We show that reduced O2 availability affects H+-ATPase pumping activity, leading to membrane depolarization and K+ loss via outward-rectifying GORK channels. Hypoxia stress also results in H2O2 accumulation in the cell that activates ROS-inducible Ca2+ uptake channels and triggers self-amplifying “ROS-Ca hub,” further exacerbating K+ loss via non-selective cation channels that results in the loss of the cell's viability. Hypoxia-induced elevation in the GABA level may restore membrane potential by pH-dependent regulation of H+-ATPase and/or by generating more energy through the activation of the GABA shunt pathway and TCA cycle. Elevated GABA can also provide better control of the ROS-Ca2+ hub by transcriptional control of RBOH genes thus preventing over-excessive H2O2 accumulation. Finally, GABA can operate as a ligand directly controlling the open probability and conductance of K+ efflux GORK channels, thus enabling plants adaptation to hypoxic conditions.

Key words: potassium homeostasis, calcium signaling, NADPH oxidase, GORK, H+-ATPase, reactive oxygen species

Hypoxia-induced elevation in the GABA level restores membrane potential thus enhancing K+ retention by controlling conductance of K+ efflux GORK channels. GABA also provides better control of “ROS-Ca2+ hub” by transcriptional control of RBOH genes thus preventing excessive H2O2 accumulation and ROS-induced K+ loss, enabling plants adaptation to hypoxic conditions.

Introduction

Soil waterlogging severely limits gas diffusion and results in hypoxic condition in the root zone, thus severely affecting plant performance and the productivity of agricultural production systems, causing up to 80% of yield reduction in sensitive species (Setter and Waters, 2003; Shabala, 2011). To a large extent, the above reduction in yield is associated with the energy crisis (Greenway and Armstrong, 2018; Armstrong et al., 2019) that compromises plant’s ability to uptake and transport essential nutrients to developing shoots (Colmer and Greenway, 2011; Shabala et al., 2014). Hypoxia stress also interferes with mitochondrial respiration, leading to a saturation of redox chains, resulting a burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Voesenek and Bailey-Serres, 2015; Yamauchi et al., 2017). The latter process comes with a significant impact on intracellular ionic homeostasis and disturbance to cell metabolism. One of the critically affected ions is potassium.

Potassium is an essential nutrient that is critical for cell’s operation (Raddatz et al., 2020); K+ has also recently emerged as an important second messenger mediating plant developmental and adaptive responses (Anschutz et al., 2014; Rubio et al., 2020). K+ retention plays a pivotal role in conferring tolerance to many abiotic stresses, including salinity (Shabala et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2018), hypoxia (Zeng et al., 2013; Gill et al., 2018, 2019), and drought (Hu and Schmidhalter, 2005; Shabala and Pottosin, 2014). Under waterlogging condition, root K+ uptake is notably suppressed upon oxygen depletion (Pang et al., 2006; Elzenga and van Veen, 2010). In barley roots, a significant K+ efflux was observed under hypoxia condition (Ma et al., 2016), leading to up to 40% reduction in K+ content (Zeng et al., 2013). The ability of roots to maintain cytosolic K+ homeostasis is regarded as an essential component for plants to acclimate to hypoxia (Mugnai et al., 2011; Barrett-Lennard and Shabala, 2013), and attributes to a plant’s ability to regulate activity of depolarization-activated outward-rectifying K+-permeable (GORK) channels in the root epidermis in various plant species (e.g., barley, Gill et al., 2018; Arabidopsis, Wang et al., 2017). In addition to being activated by membrane depolarization, GORK channels could be also directly gated by ROS (Demidchik et al., 2010). In this context, plasma membrane-based NADPH oxidase plays a critical role in ROS generation under adverse environmental conditions (Pucciariello and Perata, 2017; Liu et al., 2020), and AtrbohD mutants lacking functional NADPH oxidase have compromised ability for hypoxia-induced Ca2+ signaling and possessed a hypoxia-sensitive phenotype (Wang et al., 2017). The physiological rationale between plant’s ability to maintain cytosolic K+ homeostasis and abiotic stress tolerance lies in the fact that high cytosolic K+ levels are essential to suppress the activity of caspase-like proteases and endonucleases in plants, and the decrease in the cytosolic K+ pool may result in activation of these catabolic enzymes, which initiate programmed cell death (PCD) (Shabala et al., 2007; Demidchik et al., 2010; Peters and Chin, 2007).

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a non-proteinogenic amino acid that was first discovered in plant tissues about 70 years ago (Steward et al., 1949), but interest in GABA shifted to animals due to its high levels in the brain, which acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter (Roberts et al., 1960). GABA is mainly metabolized via a short pathway known as the GABA shunt, in which it is synthesized from L-glutamate in a reaction catalyzed by cytosolic enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) (EC 4.1.1.15) (Fait et al., 2008). GAD is a Ca2+-dependent calmodulin (CaM)-binding protein and its activity in plant extracts can be modulated by Ca2+-CaM (Baum et al., 1996; Bouché and Fromm, 2004). Otherwise, GABA synthesis may also occur via polyamine (putrescine and spermidine) degradation (Shelp et al., 2012); decarboxylation of proline under oxidative stress conditions is also considered as a possible source of GABA production (Signorelli et al., 2015). GABA catabolism occurs in the mitochondrial matrix and be catabolized by the pollen-pistil interaction 2 (pop2)-encoded GABA transaminase (GABA-T) (EC 2.6.1.19) to produce succinic semi-aldehyde and alanine (Palanivelu et al., 2003; Shelp et al., 2012).

The function of GABA in plants has attracted renewed attention following observations that GABA is largely and rapidly produced in response to a range of abiotic stresses including drought, extreme temperatures, salinity, waterlogging, and hypoxia (Michaeli and Fromm, 2015; Ramesh et al., 2017). Of these, hypoxia-induced elevation in GABA content is by all means the largest and has been reported for a long time in a broad range of plant species (Effer and Ranson, 1967; Bertani and Brambilla, 1982; Aurisano et al., 1995; Bai et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013; Salvatierra et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2019). GABA synthesis is stimulated by oxygen deprivation, due to increase in the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration under low-oxygen condition and stimulation of GAD activity via the CaM-dependent pathway (Bouché and Fromm, 2004). However, the physiological rationale behind hypoxia-induced elevation in GABA content remains to be elucidated. As such, it remains to be answered whether these changes in GABA levels are essential for plants to deal with hypoxia, or whether they are merely a by-product of hypoxia-adaptive responses. In this context, production of GABA and alanine (via the GABA shunt) has been suggested as an important adaptive mechanism to store the carbon and nitrogen that would otherwise be lost under oxygen-deficient conditions (Shelp et al., 1995; Ricoult et al., 2006; Mustroph et al., 2014). Other suggested roles include maintenance of the osmotic potential in the stressed tissues (Miyashita and Good, 2008) and preventing accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates and inhibition of cell death (Fait et al., 2005). GABA accumulation could also be involved in the regulation of the cytosolic pH balance (Bouché and Fromm, 2004) or lead to generating more energy through the activation of the GABA shunt pathway and TCA cycle (Carillo, 2018).

In our earlier work, we have reported that exogenous application of GABA to plant roots reduced the magnitude of H2O2-induced K+ loss in barley (Shabala et al., 2014) as well as stimulating the rate of the net ROS-induced Ca2+ extrusion. These results were interpreted in the context of the beneficial role of GABA in desensitizing ROS-inducible non-selective cation channels (NSCCs). Using a bioinformatic approach, we have also recently shown that GORK channels possess the F…W…E…L conserved consensus sequence (Adem et al., 2020), which operates as a GABA binding motif in mammalian systems (Manville et al., 2018) and also in aluminum (Al3+)-activated malate transporter (ALMT) plant channels (Ramesh et al., 2015). These findings pointed at the direct possibility of GABA operating upstream of ion channels and regulating their activity, thus mediating plant adaptive responses to hypoxia.

To gain additional insights about possible mechanisms behind the above processes, we took advantage of utilizing Arabidopsis mutants with altered ability for GABA accumulation. One of them is a pop2 mutant that inhibits GABA degradation resulting in higher GABA accumulation in plant tissues (Van Cauwenberghe et al., 2002). The gad1,2 double mutant with disrupted activity of GAD1 and GAD2 genes was used to prevent the stress-induced accumulation of GABA in plants (Scholz et al., 2015). By applying a range of electrophysiological and imaging techniques to these mutants, we show that hypoxia-induced increase in GABA content is essential for restoration of membrane potential (MP) and preventing ROS-induced disturbance to ion homeostasis, thus providing the mechanistic link between stress-induced elevation in the GABA level and plant adaptive responses to hypoxia.

Results

Differential ability in GABA production alters Arabidopsis tolerance to hypoxia stress

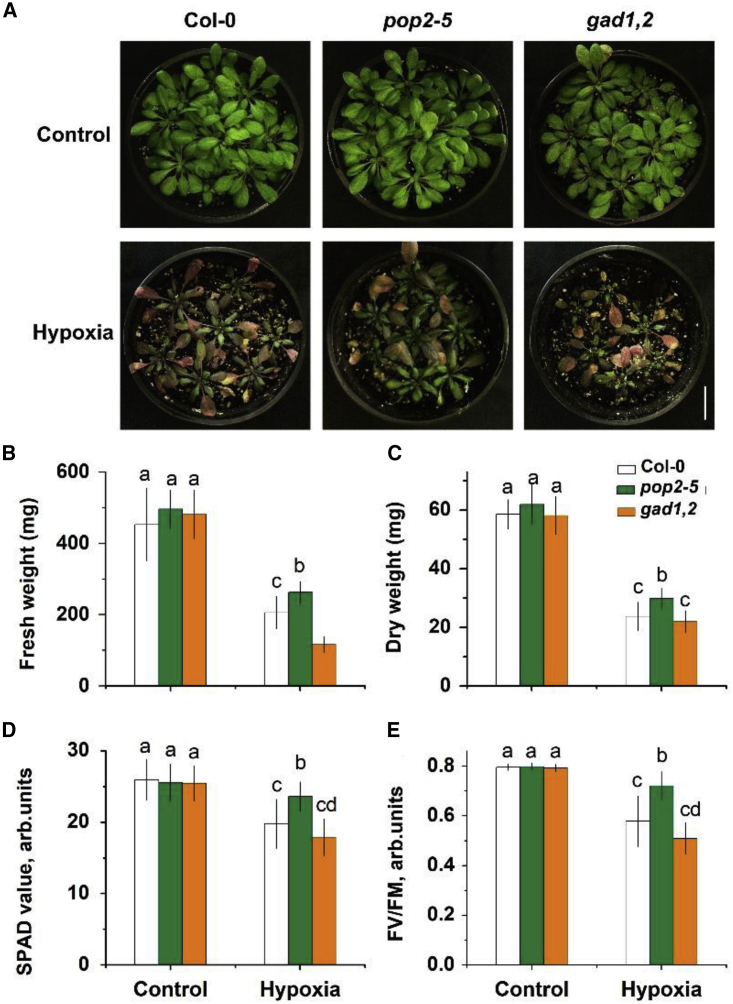

To verify the effects of GABA on a plant’s tolerance against hypoxia, two Arabidopsis thaliana mutants were used here: the pop2-5 mutant, which is unable to produce a functional GABA-T enzyme that could degrade GABA, so it accumulates more GABA in plants; and the gad1,2 mutant with compromised ability to produce GAD to catalyze the conversion of glutamate to GABA, thus accumulating less GABA. Under normal conditions, there is no phenotypic difference among Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 (Figure 1). After hypoxia treatment, gad1,2 showed significantly (P < 0.05) lower fresh weight (Figure 1B) and chlorophyll content (Figure 1D) compared with wild-type (WT) Columbia-0 (Col-0), while significantly higher chlorophyll content and chlorophyll fluorescence were observed in pop2-5 plants (Figure 1D and 1E).

Figure 1.

Phenotype detection of Arabidopsis Col, pop2-5, and gad1,2 plants grown at control and waterlogging conditions.

(A) Morphology. (B) Shoot fresh weight. (C) Shoot dry weight. (D) chlorophyll content (SPAD value). (E) Chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm). Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in pots under control conditions were subjected to waterlogging treatment for a further 2 weeks. Data is the mean ± SE (n=6 biological replicates). Data labelled with different lowercase letters is significantly different at P<0.05 level.

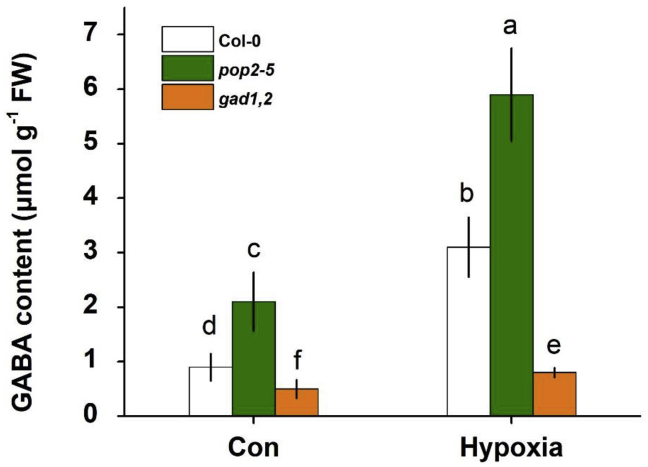

The GABA contents were measured in Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 leaves under control and hypoxia conditions. Regardless of treatment, the highest levels were in pop2-5 and the lowest were in gad1,2, with WT lying between (Figure 2). Hypoxia treatment induced a significant increase in GABA content in all genotypes (a three-fold higher GABA content in Col-0 and pop2-5 under hypoxia compared with control conditions).

Figure 2.

GABA content in the leaves of Arabidopsis Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings

Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants grown in pots under control conditions were subjected to waterlogging treatment for 1 week. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 10 biological replicates). Data labeled with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the P < 0.05 level.

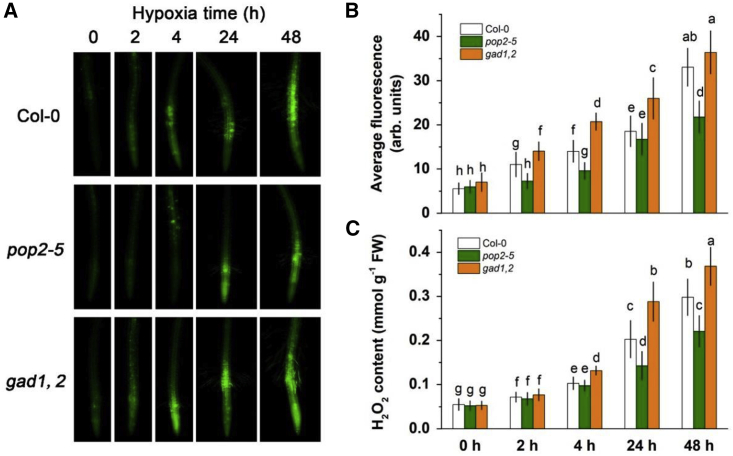

Hypoxia treatment could induce the production of H2O2, and its accumulation might damage the cells and/or disturb its ionic homeostasis. As shown in Figure 3, hypoxia stress resulted in time-dependent increase in H2O2 accumulation in roots, with 48 h hypoxia treatment, resulting in a seven-fold higher H2O2 concentration compared with control. An obvious difference among the three genotypes was spotted after 1 h hypoxia treatment, when pop2-5 showed the lowest H2O2 and gad1,2 the highest. These results indicated that disturbance to a plant’s ability to synthesize/catabolize GABA affects the pattern of hypoxia-induced H2O2 accumulation in their roots.

Figure 3.

Detection of H2O2 production in the roots of Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings at different times of hypoxia treatment

Seven-day-old seedlings grown in Petri dishes were treated with 0.1% agar solution for different time (0–48 h). Root samples were stained with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate and visualized with a fluorescence microscope

(A) Representative images.

(B) Mean fluorescence intensity from root zone.

(C)In vitro quantification of root H2O2 content at five time points by the TiCl4 method. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 10 biological replicates). Data labeled with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the P < 0.05 level.

Effects of hypoxia on K+ transport in Col, pop2-5, and gad1,2 roots

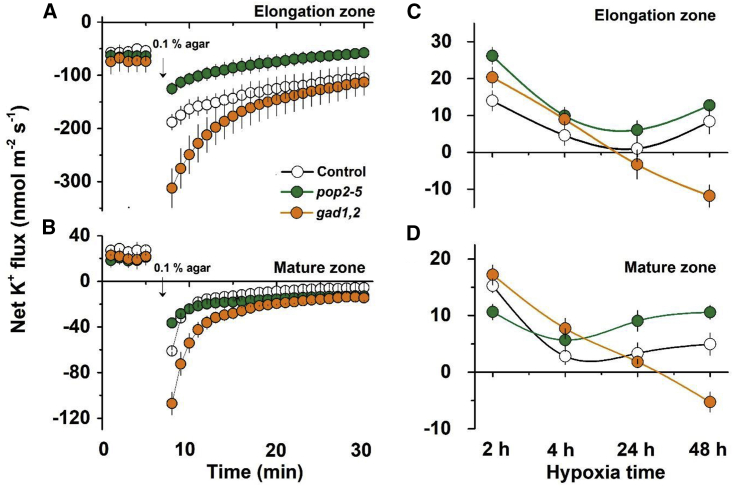

The ability of roots to maintain cytosolic K+ homeostasis is a hallmark of plant acclimation to hypoxia (Mugnai et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). To further identify the causal link between GABA accumulation and K+ homeostasis under hypoxic conditions, transient net K+ fluxes were measured from the roots of Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 Arabidopsis seedlings treated with 0.1% N2-bubbled agar (mimicking acute hypoxia) (Figure 4A and 4B). This treatment resulted in a massive net K+ leak from the roots; this leak was the strongest in gad1,2, the mutant lacking ability for GABA synthesis (in both the elongation and mature zones). Hypoxia-induced K+ efflux was much lower in pop2-5 compared with Col-0 in the elongation zone, while in the mature zone no significant difference was observed between these genotypes.

Figure 4.

Effects of hypoxia stress on net K+ fluxes in the roots of Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings

K+ fluxes measured from the elongation zone and mature root zone of 7-day-old Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings in response to transient (A and B) and long-term (C and D) hypoxia (0.1% agar) treatment. For long-term hypoxia treatment, mean fluxes (averaged of 5 min) were measured 2, 4, 24, and 48 h after 0.1% agar. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 10 biological replicates).

Qualitatively similar patterns were also observed for prolonged hypoxia exposures (Figure 4C and 4D). At 48 h after stress onset, net K+ flux patterns were pop2-5 > Col-0 > gad1,2 in both the elongation and mature zones. Importantly, gad1,2 plants were still losing K+ (net efflux), while two other genotypes were able to retain it (small but consistent K+ uptake).

Differential ability for GABA production is reflected in an altered sensitivity of K+ and Ca2+ transporters to H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals

Given the difference in H2O2 production between the three genotypes (Figure 3), we then asked the question whether the differential ability for GABA accumulation may result in differences in ROS-induced ion fluxes in plant roots.

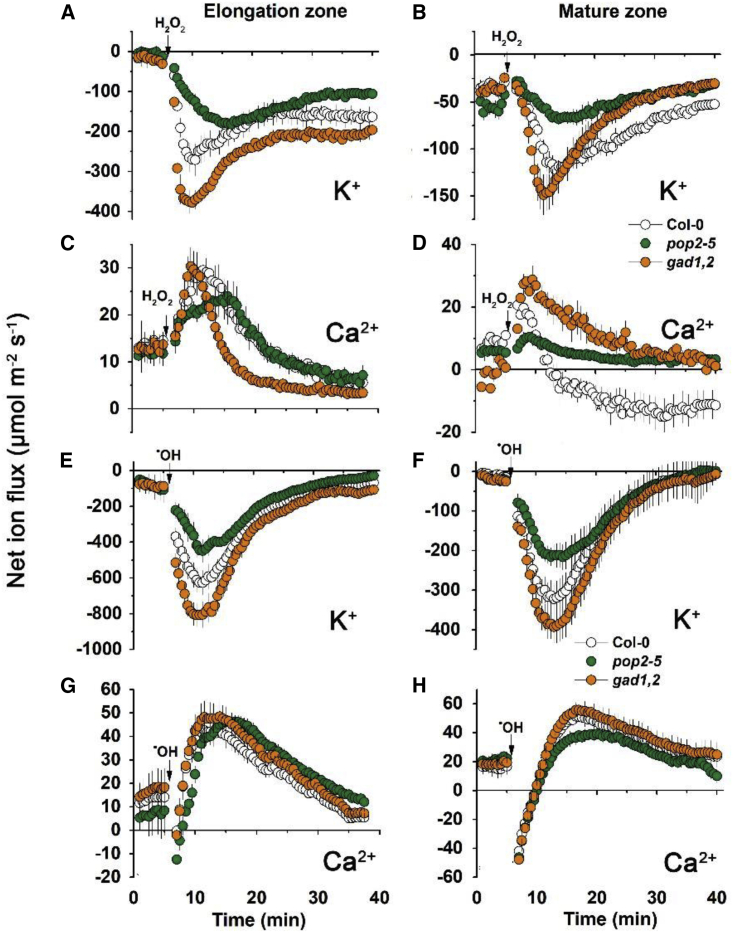

Similar to previous reports (Wang et al., 2018), application of 5 mM H2O2 caused a massive K+ loss from both the elongation and mature zone of the roots in all three Arabidopsis genotypes (Figure 5A and 5B). This H2O2-induced K+ efflux increased gradually over time, reaching peak values after 6–10 min of H2O2 treatment. The K+ efflux then gradually decreased but remained negative in the next 20 min. Compared with the response in the elongation zone, cells in the mature zone were less sensitive to H2O2 and exhibited a lower K+ efflux level. In both zones, the magnitude of K+ efflux was lowest in pop2-5 and highest in gad1,2, following the sequence gad1,2 > Col > pop2-5.

Figure 5.

Kinetics of ROS-induced net K+ and Ca2+ fluxes in the roots of Col, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings

Transient K+ and Ca2+ fluxes measured from the elongation and mature root zones of the 7-day-old Col, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings in response to acute 5 mM H2O2 or 1 mM Cu2+-ascorbate mixture (⋅OH) treatment. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 10 biological replicates).

In both the elongation and mature zones of all three Arabidopsis genotypes, application of H2O2 to the bath led to a dramatic Ca2+ influx response, with pop2-5 showing most attenuated response (Figure 5C and 5D). In the mature zone, the H2O2-induced Ca2+ uptake patterns fully matched these for K+ efflux (e.g., gad1,2 > Col > pop2-5) (Figure 5D); pop2-5 plants also had lowest H2O2-induced Ca2+ uptake in elongation zone (Figure 5C).

Transient K+ and Ca2+ fluxes were also measured from the elongation and mature root zones of Col, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings in response to another form or ROS, namely hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH), which are known to be able to directly activate GORK channels (Demidchik et al., 2010). As shown in Figure 5E and 5F, ⋅OH treatment induced massive K+ efflux from epidermal root cells in both elongation and mature zones in all genotypes. The highest response was measured in gad1,2 (~800 μmol m−2 s−1 in the elongation zone; ~400 μmol m−2 s−1 in the mature zone), followed by Col-0 (~600 and ~300 μmol m−2 s−1, respectively), and the lowest in pop2-5 (~400 and ~200 μmol m−2 s−1, respectively). ⋅OH application also resulted in a complex Ca2+ kinetics (Figure 5G and 5H, net efflux over the first few minutes, followed by net uptake and return to basal levels). However, no clear in difference was observed in responses from Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 genotypes.

GABA-overproducing pop2-5 plants maintain more negative MP values when exposed to hypoxia

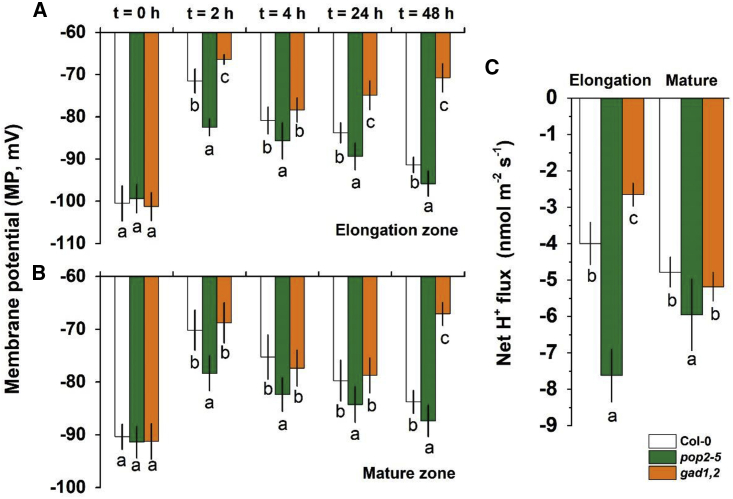

Under hypoxia (t = 0 h), MP values were more negative in the elongation zone than in the mature zone, but there was no difference among Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 (Figure 6A and 6B). In both zones, short-term (2 h) hypoxia caused significant depolarization of the MP in roots of these three genotypes. However, this depolarization was gradually recovered after reaching this peak. After 48 h of hypoxia exposure, Col-0 and pop2-5 managed to recover MP to values of about 92% and 97% of the control, respectively. The gad1,2 mutant, however, failed to restore its MP and, after a partial restoration at 24 h, collapsed and showed significant root depolarization (ca. −65 versus −92 mV in control) at the 48 h time point (mature zone data; Figure 6B). Among these three genotype plants, the depolarization level was the lowest in pop2-5 and the highest in gad1,2, leading to more negative MP values in pop2-5 and less negative MP values in gad1,2. The difference in MP patterns were consistent with differences in the magnitude of the vanadate-sensitive component of net H+ efflux measured from the root epidermis (Figure 6C), which is often taken as a proxy for H+-ATPase activity (Chen et al., 2007).

Figure 6.

Hypoxia triggered membrane potential (MP) and net H+ fluxes changes in the roots of Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings

(A and B) The time dependence of membrane potential (MP) responses to hypoxia. Steady-state MP values were measured after plant exposure to hypoxia (0.1% agar) for a specified period of time. MP values were measured for epidermal root cells in both elongation (A) and mature (B) zones of Col-0, pop2-5, and gad1,2 seedlings. Data are the mean ± SE (n = 10 biological replicates).

(C) Net H+ fluxes measured from plant roots 1 h after hypoxia onset. For each time point, data labeled with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the P < 0.05 level.

Discussion

Significant hypoxia-induced elevation in GABA content has been reported in many species (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000; Kreuzwieser et al., 2009), with exogenous GABA application being able to help plants to adapt to hypoxic conditions under soil waterlogging (Salvatierra et al., 2016; Salah et al., 2019). The physiological rationale of hypoxia-induced elevation in GABA content and the mechanistic basis underlying these beneficial effects remain, however, to be elucidated.

Previous studies have attributed stress-induced elevation in GABA content to the maintenance of the osmotic potential in stressed tissues (Miyashita and Good, 2008). However, hypoxia stress does not cause major disturbances to root osmotic potential; also, reliance on organic osmolytes for osmotic adjustment is an energetically expensive option (Munns et al., 2020) and should be used only if plants cannot achieve the latter by means of inorganic ion uptake. In this context, GABA accumulation may be potentially relevant to osmotic adjustment under conditions of combined hypoxia and salinity stress (e.g., flooding with saline water). Even so, the reported levels of GABA are in the low millimolar range (Kinnersley and Turano, 2000; Su et al., 2019) and thus unlikely to make a direct contribution to plant osmotic adjustment.

GABA accumulation has also been suggested to reduce the oxidative damage caused by ROS (Seifikalhor et al., 2019), leading to improved tolerance to oxidative stresses (AL-Quraan et al., 2015). Here, we showed reduced accumulation of H2O2 in GABA over-accumulating the pop2-5 mutant (Figure 3), and the magnitude of H2O2-induced K+ and Ca2+ flux responses was pop2-5 < Col-0 < gad1,2 (Figure 5A–5D). A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be an intrinsically higher antioxidant activity in GABA-accumulating mutant. This suggestion is consistent with the report that exogenous GABA application increased the activity of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) enzymes and reduced the production of H2O2 in plants (Kalhor et al., 2018). However, there are three reasons that make the above scenario unlikely. First, our experiments revealed no consistent patterns and significant differences in activity of major antioxidant enzymes (SOD, APX, and CAT) between genotypes (Supplemental Figure 1). Second, constitutively higher levels of AO enzymes could compromise a role of ROS as second messengers in a broad range of developmental and adaptive responses (Miller et al., 2010). Finally, higher levels of AO enzymatic activity could not explain a three- to four-fold difference in the magnitude of net K+ flux responses to acute hypoxia. Indeed, hypoxia-induced H2O2 accumulation takes some time (hours) until the ROS levels are high enough to affect cell viability, while the difference in the magnitude of hypoxia-induced K+ loss was evident within seconds after stress onset (Figure 4).

There are two possible mechanisms that could potentially explain reduced sensitivity of GABA-accumulating mutants to H2O2 (Figure 5A–5D). The first one is a desensitization of ROS-inducible ion channels. The GORK channel is one of two Shaker-like outward-rectifying K+ efflux channels in the Arabidopsis genome (alongside the SKOR channel). Garcia-Mata et al. (2010) showed that a Cys168 motif located within the S3 α helix of the voltage sensor complex was required to activate the SKOR K+ efflux channel of Arabidopsis by H2O2. Thus, it could be envisaged that the altered ability for GABA biosynthesis could lead to alterations in the amino acid composition of transporting proteins. The second possibility is a more efficient control of mechanisms that are involved in the amplification of the ROS signals, namely “Ca-ROS hub” (Demidchik and Shabala, 2018; Demidchik et al., 2018). Apoplastic ROS production via NADPH oxidase is one of the major sources of stress-induced increase in ROS levels in plant roots (Fichman and Mittler, 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Encoded by Rboh/Nox genes (Marino et al., 2012), NADPH oxidase has two Ca2+-binding helix–loop– helix structural domains and can operate in concert with ROS-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channels, forming a self-amplification mechanism. According to this Ca-ROS hub concept (Demidchik and Shabala, 2018), an increase in the apoplastic H2O2 would stimulate net Ca2+ influx into the cell (as seen in Figure 5C and 5D). This activation will result in production of additional H2O2 in the apoplast, triggering more Ca2+ influx into the cell. This positive feedback loop can increase the duration and amplitude of weak signals and shape stress-induced Ca2+ and ROS “signatures” (Demidchik et al., 2018) but, at the same time, need to be tightly controlled, to prevent uncontrollable increase in ROS content and a possible damage to key cellular structures. Earlier we showed that the expression of RBOHF (one of the key genes encoding NADPH oxidase in Arabidopsis; Marino et al., 2012) was significantly higher in gad1,2 compared with Col and pop2-5 under salt stress (Su et al., 2019). We believe that a similar scenario may be applicable to plants exposed to hypoxia (Figure 9). ROS-activated NSCCs are known to play an essential role in maintenance of intracellular K+ homeostasis under adverse environmental conditions (Shabala and Pottosin, 2014). NSCC channels are also a major route for Ca2+ uptake in plant cells (Demidchik et al., 2018). Thus, GABA-induced transcriptional changes in RBOH expression (Supplemental Figure 2) could explain the genotypic difference in H2O2-induced K+ efflux and Ca2+ uptake reported here (Figure 5A–5D).

However, the above modulation of ROS sensitivity in GABA loss- and gain-of-function mutants cannot explain the difference in plant ion flux responses to acute hypoxia (Figure 4), with the massive differences reported within the time resolution of the method (e.g., <1 min), as well as the reported difference in MP in epidermal root cells (Figure 6). This implies operation of another (additional) mechanism.

Plasma membrane-based P-type H+-ATPase is considered as a major electrogenic source responsible for MP maintenance at the plasmalemma (Palmgren and Morsomme, 2019). Being fueled by ATP, operation of the H+-ATPase pump is compromised under low-oxygen conditions (Colmer and Greenway, 2011; Shabala et al., 2014; Gill et al., 2018). It was suggested earlier that GABA could enhance plant resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses by generating more energy through the activation of the GABA shunt pathway and TCA cycle (Hijaz and Killiny, 2019). If this was the case here, then higher ATP availability in GABA-overproducing mutants could explain more negative MP values (Figure 6) and, hence, reduced K+ efflux (Figure 4) resulting from the better control of depolarization-activating outward-rectifying K+ efflux channels (Shabala et al., 2014; Gill et al., 2018). GABA also negatively regulates ALMTs (Ramesh et al., 2015; Gilliham and Tyerman, 2016) that belong to a family of plant anion channels. When open, anion channels allow the release of anions from cells to induce membrane depolarization. However, to the best of our knowledge, no reports of hypoxia-induced activation of anion channels have been reported in the literature. Hence, the applicability of the above scenario should be tested in direct patch-clamp experiments.

Another possibility is a direct control of H+-ATPase activity by GABA. Mekonnen et al. (2016) have suggested that GABA may modulate the activity of H+-ATPase via 14-3-3 proteins. The latter activate the auto-inhibited plasma membrane P-type H+ ATPases by binding the ATPases’ C terminus at a conserved threonine (Falhof et al., 2016). However, PCR analysis of 14-3-3 transcripts revealed a significant increase of some orthologs in gad1,2 mutants (Mekonnen et al., 2016) implying that H+-ATPase activity should be higher in this mutant compared with its WT. This is opposite to our observations for both H+ flux data (Figure 6C) and our MP data (Figure 6A and 6B). Also, pre-treatment with GABA resulted in an increase in H+-ATPase transcript levels in clover (Cheng et al., 2018). However, no difference in AHA expression was reported between pop2-5, Col-0, and gad1,2 genotypes under controlled conditions (Su et al., 2019) making the above scenario unlikely. Most likely, GABA control over H+-ATPase activity is related to the role of GABA in a cytosolic pH state (Crawford et al., 1994; Shelp et al., 2006). Hypoxia stress results in significant (0.4–0.8 pH units) cytosolic acidification, and synthesis of GABA consumes protons and raises pH (Felle, 2005). As operation of the H+-ATPase is a pH-dependent process (Falhof et al., 2016), GABA-related modulation in cytosolic pH may alter activity of H+-ATPases, thus affecting cellular MP.

Potassium is an essential nutrient that controls activity of over 70 enzymes (Dreyer and Uozumi, 2011; Zorb et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2018) and hence is critical to plant metabolism. High cytosolic K+ levels are also essential to control activity of catabolic enzymes (proteases and endonucleases), thus preventing PCD under stress conditions and conferring cell viability (Shabala, 2009; Demidchik et al., 2010). Depolarization-activated outward-rectifying GORK channels play a critical role in cytosolic K+ homeostasis in stress-affected plants (Anschutz et al., 2014; Rubio et al., 2020). As implied by the name, the main gating factor that controls the permeability of this channel is membrane voltage. The GORK channel opens at around Ek (Nernst potential for K+) values, and a plant’s ability to maintain more negative MP is essential to prevent stress-induced K+ efflux (Shabala et al., 2016). This may explain the better K+ retention reported here for pop2-5 mutant (Figure 4). However, our recent bioinformatic analyses have suggested that GORK channels may also be gated by several ligands including GABA and G proteins (Adem et al., 2020). In this context, it was shown that GORK channels possess the F…W…E…L conserved consensus sequence (Adem et al., 2020) that has been known to operate as a GABA binding motif in mammalian systems (Manville et al., 2018) and also in ALMT plant channels (Ramesh et al., 2015). This points to the direct possibility of GABA operating upstream of GORK channels and regulating its activity (opening), thus conferring intracellular K+ homeostasis under hypoxic conditions. The supporting evidence for this model comes from comparison of the magnitude of GABA-induced net K+ fluxes between the WT and gork1-1 Arabidopsis mutant (Adem et al., 2020). The ultimate proof for a direct control of GORK channels by GABA should come from patch-clamp experiments.

Also, in animals, GABA operates through G protein-coupled metabotropic GABAB receptors (Billinton et al., 2001). In plants, adaptive responses to oxygen deficiency requires feedback regulation of G proteins (Fukao and Baily-Serres, 2004), and we have recently shown that the GORK channel possesses a conserved consensus protein sequence for G protein binding motif E(D)RY (Deupi et al., 2012), suggesting a possibility of direct regulation of GORK channels by G protein binding (Adem et al., 2020). This signaling via G proteins may also link K+ homeostasis with H2O2 content in plant cells, as H2O2 accumulation appears to be responsible for the increased abundance of mRNA encoding a Rop GTPase-activating protein (RopGAP) that promotes the hydrolysis of Rop–GTP to Rop–GDP (Fukao and Baily-Serres, 2004).

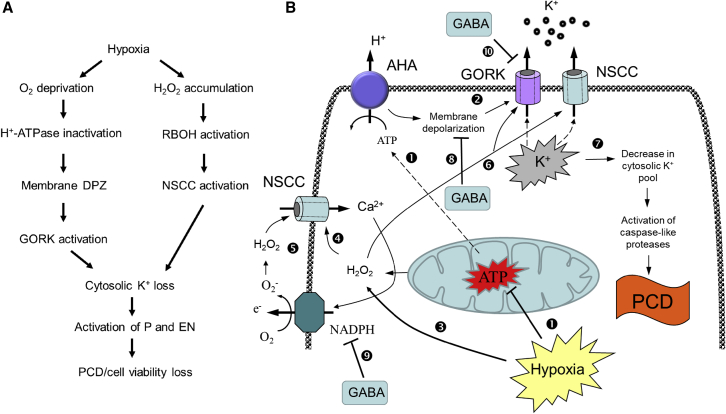

In conclusion, the following model is suggested (Figure 7). Hypoxia stress reduces O2 availability and compromise mitochondria’s capability for ATP production (➊). This reduces H+-ATPase pumping activity and leads to membrane depolarization (➋) thus activating GORK channels and resulting in K+ loss through the cytosol. Hypoxia stress also results in H2O2 accumulation in the cell (➌) that activates ROS-inducible Ca2+ uptake channels (➍) and triggers self-amplifying ROS-Ca hub (➎). This leads to a rapid accumulation of H2O2 in the cell and activation of K+-permeable NSCCs leading to a further decline in the cytosolic K+ pool (➏). The latter triggers activation of catabolic caspase-like proteases and endonucleases and results in the loss of cell viability and PCD (➐). Hypoxia-induced elevation of the GABA levels restore MP by pH-dependent regulation of H+-ATPase and/or by generating more energy through the activation of the GABA shunt pathway and TCA cycle (➑). Elevated GABA levels can also provide better control of the ROS-Ca2+ hub by transcriptional control of RBOH genes, thus preventing over-excessive H2O2 accumulation (➒). Finally, GABA can operate as a ligand directly controlling the open probability and conductance of K+ efflux GORK channels (➓).

Figure 7.

Tentative model explaining the role of GABA in hypoxia response

(A) Hypoxia-induced disturbance to K+ homeostasis. (B) The function of elevated GABA level in alleviating hypoxia stress. DPZ – depolarization; P – proteases; EN – endonucleases; GORK – depolarization-activated outward rectifying K+ channel; NSCC – non-selective cation channel. AHA – H+-ATPase. See text for details.

Methods

Plant materials and treatments

Arabidopsis WT Col-0 was used as the wild type. Seeds of loss-of-function mutants (all in the Col-0 background) gad1,2 and pop2-5 mutants were kindly provided by Frank Ludewig (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany). Seeds were surface sterilized with 1 ml of commercial bleach (1% [v/v] NaClO) for 10 min, and then washed thoroughly with sterilized distilled water. Seeds were sown in Petri dishes containing 1% (w/v) Phytogel, half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium, and 0.5% (w/v) sucrose (pH 5.8), sealed with 3M micro-pore tape, and then transferred into a growth chamber with 16 h/8 h light/dark cycles, 100 μmol m−2 s−1 photon flux density, and 22°C. The Petri dishes were oriented upright, allowing the roots to grow down along the surface without penetrating into the medium.

Hypoxic treatment was imposed on the 10-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings by submersion in 0.1% (w/v) agar solution pre-bubbled with high purity N2 (Coregas, Sydney, NSW Australia). The treatment solution contained 10 mM KCl, 5 mM Ca2+–MES (pH 6.1), and 0.1% (w/v) agar, which was dissolved by boiling while being stirred, and the solution was cooled down to room temperature, and then bubbled with high purity N2. For acute hypoxia application, the N2-bubbled 0.1% (w/v) agar solution was used to quickly replace the bath solution (see Zeng et al., 2014 for details). For H2O2 and MP analysis, 10-day-old Col-0, gad1,2, and pop2-5 seedlings were submerged in agar solution in a transparent container for 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h, this approach was taken following our earlier work on Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2016).

Whole-plant physiological assessment

For pot phenotyping experiments, seeds of Col-0, gad1,2, and pop2-5 were sown in 0.2 l pots filled with peat moss, perlite, vermiculite, and coarse sand, at a ratio of 2:1:1:1 (v/v), and grown in a growth chamber at a 14/10 h light (photosynthetically active radiation 100 μmol m−2 s−1)/dark regime and at 22°C for 4 weeks. Waterlogging treatment was then implemented by immersing pots of 4-week-old plants at a water level 1.0 cm above the soil surface and maintaining them for another 3 weeks. The fresh and dry weight of the above-ground portion of each plant was then determined. Leaf chlorophyll content was measured using an SPAD meter (SPAD-502, Minolta, Japan). Measurements were taken for at least six biological replicates for each treatment in a single experiment.

For chlorophyll fluorescence analysis, plants were adapted in a dark chamber for 30 min before measurement. The maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (chlorophyll fluorescence Fv/Fm ratio) was recorded at a saturating actinic light (660 nm) intensity of 1100 μmol m−2 s−1 using an OS-30p chlorophyll fluorometer (Opti-Sciences, USA). All non-distractive measurements were taken on rosette leaves from at least five biological replicates for each treatment.

Extraction and quantification of GABA

GABA content determination was carried out as described by Su et al. (2019) and Scholz et al. (2017), and was analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (AB Sciex-API 4000, Germany). For samples preparation, 250 mg fresh tissues from leaves was harvested, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and weighed for the determination of GABA per gram fresh weight. After maceration, the amino acids (including GABA) were extracted twice with a total of 2 ml of methanol on ice, and supernatants were combined, dried, and re-suspended in 500 μl methanol. This extract was diluted 1:20 (v/v) with water containing the internal standard. The algal amino acid mix (13C,15N; Isotec, Miamisburg, OH, USA) was used as an internal standard at a mix concentration of 10 μg ml−1 in all samples.

Histochemical detection of H2O2

The production of H2O2 in root was detected using a H2O2-sensitive fluorescent probe, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (catalog no. D6883, Sigma-Aldrich) (Bose et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). The Arabidopsis roots were collected after 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h of hypoxia treatment, and then washed with 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer and immersed in 25 μM H2DCFDA buffer containing 10 mM KCl, 5 mM Ca2+ (pH 6.1) for 30 min in the dark. The stained roots were washed thoroughly in distilled water to remove residual dye before measuring fluorescence intensity. Fluorescent signals were visualized using a fluorescent microscope (Leica MZ12; Leica Microsystems) and collected using excitation and emission wavelengths at 488 and 525 nm, respectively, for H2DCFDA. Then, fluorescence images were analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH, USA) based on their integrated density. For each treatment, at least 10 biological replicates (individual roots) were measured.

The second (quantitative) method followed the procedure of Hossain et al. (2010); 0.5 g fresh roots was ground in 5 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), then centrifuged at ~11 900 g for 15 min at 4°C. The yellow color developed after reaction of 3 ml supernatant with 1 ml 0.1% TiCl4 containing 20% H2SO4 for 10 min at room temperature. The absorbance was then recorded at 410 nm.

Ion-selective microelectrode preparation

Net fluxes of K+, Ca2+, and H+ were measured using the MIFE (non-invasive microelectrode ion flux estimation) (University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia) technique. The theory of MIFE measurements and all details of electrode fabrication and calibration are given in our previous publication (Shabala et al., 1997, 2006). In brief, microelectrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries, oven dried, and silanized with chlorotributylsilane (tributylchlorosilane, catalog no. 282707, Sigma-Aldrich). After cooling, microelectrode tips were flattened to 2–3 μm in diameter and then back-filled with respective backfilling solutions (200 mM KCl for K+; 500 mM CaCl2 for Ca2+; 15 mM NaCl + 40 mM KH2PO4, with pH adjusted to 6.0 using NaOH for H+) and front-filled with respective ion-selective ionophore cocktails (catalog nos. 99311 for K+, 99310 for Ca2+, and 95291 for H+, all from Sigma-Aldrich). Prepared microelectrodes were calibrated in respective sets of the standard solutions before and after measurements.

Non-invasive ion flux measurements

Net K+, Ca2+, and H+ fluxes were measured from the elongation (~300 μm from the root tip) and mature (~1500 μm from the root tip) root zones of Arabidopsis seedlings. Before measurement, roots of intact seedlings were immobilized in a 5 ml Perspex measuring chamber (10.5 × 0.8 × 2.0 cm), and 5 ml of basic salt medium (0.5 mM KCl and 0.1 mM CaCl2 [pH 5.6]) was added into the chamber for adaptation. During measurements, microelectrodes were moved in a 12 s square-wave cycle using a computer-controlled hydraulic micromanipulator with a travel range of 90 μm. Steady-state fluxes were measured for 5 min, and then the appropriate treatment was administered, followed by another 20–30 min. Voltage outputs of electrodes were recorded using CHART software and then converted into net flux data using the MIFEFLUX program (Shabala et al., 2006). At least 10 replicates were used for each treatment.

MP measurements

The roots of an intact Arabidopsis seedling were gently secured in a measuring chamber in a horizontal position using a Parafilm strip and small plastic blocks. The seedlings were then placed in a 10 ml Perspex measuring chamber filled with previously N2-bubbled agar solution. Conventional KCl-filled Ag-AgCl microelectrodes were used for MP measurements in the elongation and mature root zones (Bose et al., 2013). During the MP measurement, the microelectrodes were impaled into the external cortex cells using a manually operated hydraulic micromanipulator (MHW-4, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Values of MP were measured at 0, 2, 4, 24, and 48 h of hypoxia treatment. For each Arabidopsis genotype, MP values of elongation and mature zones were determined from roots of at least six individual seedlings.

Antioxidant enzymatic activity assays

Fresh root tissues (0.3 g) were homogenized in 5 ml of 50 mM cool phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), containing 1 mM EDTA 1% (w/v) PVP for assays of SOD, CAT, or combinations, with the addition of 1 mM ascorbic acid (AsA) in the case of APX determination. The homogenates were centrifuged at 12 000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were used for assays of enzyme activity. SOD activities was analyzed using the methods described previously (Wu et al., 2015). CAT activity was spectrophotometrically measured by monitoring the consumption of H2O2 at 240 nm for 3 min (Huang et al., 2006). APX activity was measured by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm as AsA was oxidized for at least 1 min in 3 ml reaction mixture, as described by Jin et al. (2013).

Quantitative and real-time PCR analysis

The extraction of total RNA, purity of RNA, first-strand cDNA synthesis, and operation of quantitative real-time PCR reactions were conducted as described previously (Wu et al., 2015).

The cDNA was amplified using the following specific primers: for actin, forward 5′-TCGTTTCGCTTTCCTTAG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTCACCATTCCAGTTCC-3'; for rbohD, forward 5′-ATTACAAGCACCAAACCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TTCTCCGACCATCTCACTA-3'; for rbohF, forward 5′-TCCAATGTCCTGCGGTTTC-3′ and reverse 5′-TGTTGTTTCGTCGGCTCTG-3'.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). All data presented in the figures are means ± SE. The significant differences were compared using Tukey's multiple range test (P < 0.05).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572169), the project of International Cooperation and Exchanges of NSFC (31961143001), the project of Basic and Applied Basic Research of Guangdong Province (2019A1515110856), China National Distinguished Expert Project (WQ20174400441), grant 31961143001for Joint Research Projects between Pakistan Science Foundation and National Natural Science Foundation of China, and funding from Australian Research Council.

Author contributions

Q.W., M.Y., and S. S. designed the research. Q.W., N.S., X.H., J.C., and L. S. conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. Q.W., M.Z., M.Y., and S. S. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final article.

Acknowledgments

No conflict of interest declared.

Published: May 1, 2021

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Min Yu, Email: yumin0820@hotmail.com.

Sergey Shabala, Email: sergey.shabala@utas.edu.au.

Supplemental information

References

- Adem G.D., Chen G., Shabala L., Chen Z., Shabala S. GORK channel: a master switch of plant metabolism? Trends. Plant Sci. 2020;25:434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AL-Quraan N.A., Al-Smadi M., Swaleh A.F. GABA metabolism and ROS induction in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik) plants by synthetic 1,2,3-thiadiazole compounds. J. Plant Interact. 2015;10:185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Anschutz U., Becker D., Shabala S. Going beyond nutrition: regulation of potassium homeostasis as a common denominator of plant adaptive responses to environment. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:670–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong W., Beckett P.M., Colmer T.D., Setter T.L., Greenway H. Tolerance of roots to low oxygen: 'anoxic' cores, the phytoglobin-nitric oxide cycle, and energy or oxygen sensing. J. Plant Physiol. 2019;239:92–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurisano N., Bertani A., Reggiani R. Anaerobic accumulation of 4-aminobutyrate in rice seedlings; causes and significance. Phytochemistry. 1995;38:1147–1150. [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q., Chai M., Gu Z., Cao X., Li Y., Liu K. Effects of components in culture medium on glutamate decarboxylase activity and gamma-aminobutyric acid accumulation in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) during germination. Food Chem. 2009;116:152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Lennard E.G., Shabala S. The waterlogging/salinity interaction in higher plants revisited-focusing on the hypoxia-induced disturbance to K+ homeostasis. Funct. Plant Biol. 2013;40:872–882. doi: 10.1071/FP12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum G., Lev-Yadun S., Fridmann Y. Calmodulin binding to glutamate decarboxylase is required for regulation of glutamate and GABA metabolism and normal development in plants. EMBO J. 1996;15:2988–2996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertani A., Brambilla I. Effect of decreasing oxygen concentrations on some aspects of protein and amino-acid metabolism in rice roots. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 1982;107:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Billinton A., Baird V.H., Thom M., Duncan J., Bowery N. GABAB(1) mRNA expression in hippocampal sclerosis associated with human temporal lobe epilepsy. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;86:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J., Shabala L., Pottosin I., Zeng F., Velarde-Buendía A.M., Massart A., Poschenrieder C., Hariadi Y., Shabala S. Kinetics of xylem loading, membrane potential maintenance, and sensitivity of K+-permeable channels to reactive oxygen species: physiological traits that differentiate salinity tolerance between pea and barley. Plant Cell. Environ. 2014;37:589–600. doi: 10.1111/pce.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J., Xie Y., Shen W., Shabala S. Haem oxygenase modifies salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by controlling K⁺ retention via regulation of the plasma membrane H⁺-ATPase and by altering SOS1 transcript levels in roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:471–481. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N., Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends. Plant Sci. 2004;9:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carillo P. GABA shunt in durum wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018;9:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.00100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Pottosin I.I., Cuin T.A., Fuglsang A.T., Tester M., Jha D., Zepeda-Jazo I., Zhou M., Palmgren M.G., Newman I.A. Root plasma membrane transporters controlling K⁺/Na⁺ homeostasis in salt-stressed barley. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1714–1725. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.110262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng B., Li Z., Liang L., Cao Y., Zeng W., Zhang X., Ma X., Huang L., Nie G., Liu W. The γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) alleviates salt stress damage during seeds germination of white clover associated with Na+/K+ transportation, dehydrins accumulation, and stress-related genes expression in white clover. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2520. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmer T.D., Greenway H. Ion transport in seminal and adventitious roots of cereals during O2 deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:39–57. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford L.A., Bown A.W., Breitkreuz K.E., Guinel F.C. The synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric-acid in response to treatments reducing cytosolic pH. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:865–871. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Shabala S. Mechanisms of cytosolic calcium elevation in plants: the role of ion channels, calcium extrusion systems and NADPH oxidase-mediated “ROS-Ca2+ Hub”. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018;45:9–27. doi: 10.1071/FP16420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Cuin T.A., Svistunenko D., Smith S.J., Miller A.J., Shabala S., Sokolik A., Yurin V. Arabidopsis root K+-efflux conductance activated by hydroxyl radicals: single-channel properties, genetic basis and involvement in stress-induced cell death. J. Cell. Sci. 2010;123:1468–1479. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Shabala S., Isayenkov S., Cuin T.A., Pottosin I. Calcium transport across plant membranes: mechanisms and functions. New Phytol. 2018;220:49–69. doi: 10.1111/nph.15266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deupi X., Edwards P., Ankita S., Benjamin N., Daniel O., Schertlera G., Standfussa J. Stabilized G protein binding site in the structure of constitutively active metarhodopsin-II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;116:14547–14556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114089108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer I., Uozumi N. Potassium channels in plant cells. FEBS J. 2011;278:4293–4303. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effer W.R., Ranson S.L. Respiratory metabolism in buckwheat seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1967;42:1042–1052. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.8.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzenga I., van Veen H. Waterlogging and plant nutrient uptake. In: Mancuso S., Shabala S., editors. Waterlogging Signalling and Tolerance in Plants. Springer; Berlin-Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fait A., Fromm H., Walter D., Galili G., Fernie A.R. Highway or byway: the metabolic role of the GABA shunt in plants. Trends. Plant Sci. 2008;13:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fait A., Yellin A., Fromm H. GABA shunt deficiencies and accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates: insight from Arabidopsis mutants. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falhof J., Pedersen J.T., Fuglsang A.T., Palmgren M. Plasma membrane H+-ATPase regulation in the center of plant physiology. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle H.H. pH regulation in anoxic plants. Ann. Bot. 2005;96:519–532. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichman Y., Mittler R. Rapid systemic signaling during abiotic and biotic stresses: is the ROS wave master of all trades? Plant J. 2020;102:887–896. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukao T., Baily-Serres J. Plant responses to hypoxia—is survival a balancing act? Trends. Plant Sci. 2004;9:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C., Wang J., Gajdanowicz P., Gonzalez W., Hills A., Donald N., Riedelsberger J., Amtmann A., Dreyer I., Blatt M.R. Minimal cysteine motif required to activate the SKOR K⁺ channel of Arabidopsis by the reactive oxygen species H₂O₂. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:29286–29294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M.B., Zeng F.R., Shabala L., Böhm J., Zhang G., Zhou M., Shabala S. The ability to regulate voltage-gated K+-permeable channels in the mature root epidermis is essential for waterlogging tolerance in barley. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:667–680. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M.B., Zeng F.R., Shabala L., Zhang G., Yu M., Demidchik V., Shabala S., Zhou M. Identification of QTL related to ROS formation under hypoxia and their association with waterlogging and salt tolerance in barley. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliham M., Tyerman S.D. Linking metabolism to membrane signaling: the GABA-malate connection. Trends. Plant Sci. 2016;21:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway H., Armstrong W. Energy-crises in well-aerated and anoxic tissue: does tolerance require the same specific proteins and energy-efficient transport? Funct. Plant Biol. 2018;45:877–894. doi: 10.1071/FP17250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijaz F., Killiny N. Exogenous GABA is quickly metabolized to succinic acid and fed into the plant TCA cycle. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019;14:e1573096. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1573096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M.A., Hasanuzzaman M., Fujita M. Up-regulation of antioxidant and glyoxalase systems by exogenous glycinebetaine and proline in mung bean confer tolerance to cadmium stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plant. 2010;16:259–272. doi: 10.1007/s12298-010-0028-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Schmidhalter U. Drought and salinity: a comparison of their effects on mineral nutrition of plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nut. 2005;168:541–549. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Xu S., Xuan W., Li M., Cao Z., Liu K., Ling T., Shen W. Carbon monoxide alleviates salt-induced oxidative damage in wheat seedling leaves. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2006;48:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q., Zhu K., Cui W., Xie Y., Han B., Shen W. Hydrogen gas acts as a novel bioactive molecule in enhancing plant tolerance to paraquat-induced oxidative stress via the modulation of heme oxygenase-1 signalling system. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36:956–969. doi: 10.1111/pce.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhor M.S., Aliniaeifard S., Seif M., Asayesh E.J., Bernard F., Hassani B., Li T. Enhanced salt tolerance and photosynthesis performance: implication of ɤ-amino butyric acid application in salt-exposed lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018;130:157–172. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley A.M., Turano F.J. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and plant responses to stress. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2000;19:479–509. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzwieser J., Hauberg J., Howell K.A., Carroll A., Rennenberg H., Millar A.H., Whelan J. Differential response of grey poplar leaves and roots underpins stress adaptation during hypoxia. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:461–473. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M.M., Yu H.Y., Ouyang B., Shi C.M., Demidchik V., Hao Z.F., Yu M., Shabala S. NADPH oxidases and the evolution of plant salinity tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43:2957–2968. doi: 10.1111/pce.13907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G., Liang Y., Wu X., Li J., Ma W., Zhang Y., Gao H. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase (mMDH) is involved in exogenous GABA increasing root hypoxia tolerance in muskmelon plants. Sci. Hort. 2019;258:108741. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Zhu M., Shabala L., Zhou M., Shabala S. Conditioning of roots with hypoxia increases aluminum and acid stress tolerance by mitigating activation of K+ efflux channels by ROS in barley: insights into cross-tolerance mechanisms. Plant Cell. Physiol. 2016;57:160–173. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manville R.W., Papanikolaou M., Abbott G.W. Direct neurotransmitter activation of voltage-gated potassium channels. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1847. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04266-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino D., Dunand C., Puppo A., Pauly N. A burst of plant NADPH oxidases. Trends. Plant Sci. 2012;17:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen D.W., Flügge U.I., Ludewig F. Gamma-aminobutyric acid depletion affects stomata closure and drought tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2016;245:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S., Fromm H. Closing the loop on the GABA shunt in plants: are GABA metabolism and signaling entwined? Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:419. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E.W., Dickinson B.C., Chang C.J. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide uptake to regulate downstream intracellular signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:15681–15686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005776107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y., Good A.G. Contribution of the GABA shunt to hypoxia induced alanine accumulation in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. Physiol. 2008;49:92–102. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnai S., Marras A.M., Mancuso S. Effect of hypoxic acclimation on anoxia tolerance in vitis roots: response of metabolic activity and K+ fluxes. Plant Cell. Physiol. 2011;52:1107–1116. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R., Passioura J.B., Colmer T.D., Byrt C.S. Osmotic adjustment and energy limitations to plant growth in saline soil. New Phytol. 2020;225:1091–1096. doi: 10.1111/nph.15862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph A., Barding G.A., Kaiser K.A., Larive C.K., Bailey-Serres J. Characterization of distinct root and shoot responses to low-oxygen stress in Arabidopsis with a focus on primary C- and N-metabolism. Plant Cell. Environ. 2014;37:2366–2380. doi: 10.1111/pce.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanivelu R., Brass L., Edlund A.F., Preuss D. Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell. 2003;114:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren M., Morsomme P. The plasma membrane H+-ATPase, a simple polypeptide with a long history. Yeast. 2019;36:201–210. doi: 10.1002/yea.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang J., Newman I., Mendham N., Zhou M., Shabala S. Microelectrode ion and O2 fluxes measurements reveal differential sensitivity of barley root tissues to hypoxia. Plant Cell. Environ. 2006;29:1107–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J., Chin C. Potassium loss is involved in tobacco cell death induced by palmitoleic acid ceramide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;465:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucciariello C., Perata P. New insights into reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide signalling under low oxygen in plants. Plant Cell. Environ. 2017;40:473–482. doi: 10.1111/pce.12715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raddatz N., Morales de Los Ríos L., Lindahl M., Quintero F.J., Pardo J.M. Coordinated transport of nitrate, potassium, and sodium. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:247. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh S.A., Tyerman S.D., Gilliham M., Xu B. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:1577–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2415-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh S.A., Tyerman S.D., Xu B., Bose J., Kaur S., Conn V., Domingos P., Ullah S., Wege S., Shabala S. GABA signalling modulates plant growth by directly regulating the activity of plant-specific anion transporters. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7879. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricoult C., Echeverria L.O., Cliquet J.B., Limami A.M. Characterization of alanine aminotransferase (AlaAT) multigene family and hypoxic response in young seedlings of the model legume Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:3079–3089. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts E., Eidelberg E., Carl C.P., John R.S. Metabolic and neurophysiological roles of γ-aminobutyric acid. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 1960;2:279–332. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio F., Nieves-Cordones M., Horie T., Shabala S. Doing 'business as usual' comes with a cost: evaluating energy cost of maintaining plant intracellular K+ homeostasis under saline conditions. New Phytol. 2020;225:1097–1104. doi: 10.1111/nph.15852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah A., Li J., Ge J., Cao C., Li H., Wang Y., Liu Z., Zhan M., Zhao M. Morphological and physiological responses of maize seedlings under drought and waterlogging. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2019;21:1199–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatierra A., Pimentel P., Almada R., Hinrichsen P. Exogenous GABA application transiently improves the tolerance to root hypoxia on a sensitive genotype of Prunus rootstock. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016;125:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz S.S., Malabarba J., Reichelt M., Heyer M., Ludewig F., Mithöfer A. Evidence for GABA-induced systemic GABA accumulation in Arabidopsis upon wounding. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:388. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz S.S., Reichelt M., Mekonnen D.W., Ludewig F., Mithöfer A. Insect herbivory-elicited GABA accumulation in plants is a wound-induced, direct, systemic, and jasmonate-independent defense response. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifikalhor M., Aliniaeifard S., Hassani B., Niknam V., Lastochkina O. Diverse role of γ-aminobutyric acid in dynamic plant cell responses. Plant Cell. Rep. 2019;38:847–867. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02396-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setter T., Waters I. Review of prospects for germplasm improvement for waterlogging tolerance in wheat, barley and oats. Plant Soil. 2003;253:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shabala L., Ross T., McMeekin T., Shabala S. Non-invasive microelectrode ion flux measurements to study adaptive responses of microorganisms to the environment. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:472–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S. Salinity and programmed cell death: unravelling mechanisms for ion specific signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:709–712. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S. Physiological and cellular aspects of phytotoxicity tolerance in plants: the role of membrane transporters and implications for crop breeding for waterlogging tolerance. New Phytol. 2011;190:289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Pottosin I. Regulation of potassium transport in plants under hostile conditions: implications for abiotic and biotic stress tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 2014;151:257–279. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Bose J., Fuglsang A.T., Pottosin I. On a quest for stress tolerance genes: membrane transporters in sensing and adapting to hostile soils. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:1015–1031. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Cuin T.A., Prismall L., Nemchinov L.G. Expression of animal CED-9 anti-apoptotic gene in tobacco modifies plasma membrane ion fluxes in response to salinity and oxidative stress. Planta. 2007;227:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0606-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Newman I.A., Morris J. Oscillations in H+ and Ca2+ ion fluxes around the elongation region of corn roots and effects of external pH. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:111–118. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Shabala L., Barcelo J., Poschenrieder C. Membrane transporters mediating root signalling and adaptive responses to oxygen deprivation and soil flooding. Plant Cell. Environ. 2014;37:2216–2233. doi: 10.1111/pce.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B.J., Brown A.W., Faure D. Extracellular gamma-aminobutyrate mediates communication between plants and other organisms. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:414–420. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.088955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B.J., Mullen R.T., Waller J.C. Compartmentation of GABA metabolism raises intriguing questions. Trends. Plant Sci. 2012;17:57–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B.J., Walton C.S., Snedden W.A., Tuin L.G., Oresnik I.J., Layzell D.D. GABA shunt in developing soybean seeds is associated with hypoxia. Physiol. Plant. 1995;94:219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Signorelli S., Dans P.D., Coitiño E.L., Borsani O., Monza J. Connecting proline and γ-aminobutyric acid in stressed plants through non-enzymatic reactions. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward F.C., Thompson J.F., Dent C.E. γ-Aminobutyric acid: a constituent of the potato tuber? Science. 1949;110:439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Su N., Wu Q., Chen J., Shabala L., Mithöfer A., Wang H., Qu M., Yu M., Cui J., Shabala S. GABA operates upstream of H+-ATPase and improves salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by enabling cytosolic K+ retention and Na+ exclusion. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:6349–6361. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cauwenberghe O.R., Makhmoudov A., McLean M.D., Clark S.M., Shelp B.J. Plant pyruvate-dependent gamma aminobutyrate transaminase: identification of an Arabidopsis cDNA and its expression in Escherichia coli. Can. J. Bot. 2002;80:933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Voesenek L.A.C.J., Bailey-Serres J. Flood adaptive traits and processes: an overview. New Phytol. 2015;206:57–73. doi: 10.1111/nph.13209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Chen Z., Liu X., Colmer T.D., Shabala L., Salih A., Zhou M., Shabala S. Revealing the roles of GORK channels and NADPH oxidase in acclimation to hypoxia in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:3191–3204. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Chen Z., Liu X., Colmer T.D., Zhou M., Shabala S. Tissue-specific root ion profiling reveals essential roles for the CAX and ACA calcium transport systems for hypoxia response in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:3747–3762. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Shabala L., Zhou M., Shabala S. Hydrogen peroxide induced root Ca2+ and K+ fluxes correlate with salt tolerance in cereals: towards the cell-based phenotyping. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:e702. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Zhang X., Giraldo P.J., Shabala S. It is not all about sodium: revealing tissue specificity and signalling roles of potassium in plant responses to salt stress. Plant Soil. 2018;431:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Su N., Cai J., Shen Z., Cui J. Hydrogen-rich water enhances cadmium tolerance in Chinese cabbage by reducing cadmium uptake and increasing antioxidant capacities. J. Plant Physiol. 2015;175:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T., Yoshioka M., Fukazawa A., Mori H., Nishizawa N.K., Tsutsumi N., Yoshioka H., Nakazono M. An NADPH oxidase RBOH functions in rice roots during lysigenous aerenchyma formation under oxygen-deficient conditions. Plant Cell. 2017;29:775–790. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R., Guo Q., Gu Z. GABA shunt and polyamine degradation pathway on γ-aminobutyric acid accumulation in germinating fava bean (Vicia faba L.) under hypoxia. Food Chem. 2013;136:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F., Shabala L., Zhou M., Zhang G., Shabala S. Barley responses to combined waterlogging and salinity stress: separating effects of oxygen deprivation and elemental toxicity. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:313. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng F.R., Konnerup D., Shabala L., Zhou M.X., Colmer T.D., Zhang G.P., Shabala S. Linking oxygen availability with membrane potential maintenance and K+ retention of barley roots: implications for waterlogging stress tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:2325–2338. doi: 10.1111/pce.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorb C., Senbayram M., Peiter E. Potassium in agriculture—status and perspectives. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:656–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.