Abstract

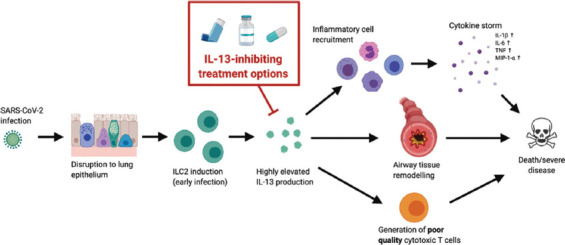

The ongoing coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic urgently requires the availability of interventions that improve outcomes for those with severe disease. Since severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection is characterized by dysregulated lung mucosae, and that mucosal homeostasis is heavily influenced by interleukin (IL)-13 activity, we explore recent findings indicating that IL-13 production is proportional to disease severity. We propose that excessive IL-13 contributes to the progression of severe/fatal COVID-19 by (1) promoting the recruitment of immune cells that express inflammatory cytokines, causing a cytokine storm that results in widespread destruction of lung tissue, (2) directly facilitating tissue-remodeling that causes airway hyperinflammation and obstruction, and (3) diverting the immune system away from developing high-quality cytotoxic T cells that confer effective anti-viral immunity. These factors may cumulatively result in significant lung distress, multi-organ failure, and death. Here, we suggest repurposing existing IL-13-inhibiting interventions, including antibody therapies routinely used for allergic lung hyperinflammation, as well as viral vector-based approaches, to alleviate disease. Since many of these strategies have previously been shown to be both safe and effective, this could prove to be a highly cost-effective solution.

Relevance for Patients:

There remains a desperate need to establish medical interventions that reliably improves outcomes for patients suffering from COVID-19. We explore the role of IL-13 in maintaining homeostasis at the lung mucosae and propose that its dysregulation during viral infection may propagate the hallmarks of severe disease – further exploration may provide a platform for invaluable therapeutics.

Keywords: coronavirus disease-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, interleukin-13, lung mucosae, ILC2, inflammation, cytokine storm, interleukin-4/interleukin-13 antagonists, IL-13Ra2

Interleukin (IL)-13 is critical in maintaining mucosal homeostasis, being implicated in allergy, parasitic and viral infection, as well as vaccine-specific immunity [1-8]. At the lung mucosae, IL-13 is expressed by a range of innate immune cell types, particularly type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), whose rapid response to external stimuli (pathogens, toxins, and allergens) acts to facilitate barrier tissue responses and condition downstream immune outcomes [9-12]. IL-13 activity at the lung triggers smooth muscle contraction, mucus secretion, and the recruitment/activation of inflammatory immune cells. However, overexpression of IL-13 is associated with allergic lung hyperinflammation, airway tissue remodeling, and hyperresponsiveness [1,13-15]. Interestingly, IL-13 dysregulation is known to be a hallmark of several disease conditions, including allergic pulmonary diseases, atopic dermatitis, and also some cancers [16-19]. Since coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is fundamentally characterized by dysregulation of the lung mucosae, we postulate that IL-13 is associated with destructive lung hyperinflammation/immune activity that underpins severe COVID-19 disease progression. Here we discuss how IL-13-inhibiting interventions could be repurposed to benefit severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2)-infected patients.

By studying a series of viruses, we have recently shown that ILC2s produce significant IL-13 following viral infection/vaccination 24 h post-encounter [10], where the level of ILC2-derived IL-13 is dependent on the virus (e.g., fowlpox <influenza <rhinovirus <Vaccinia virus) [11,20]. Moreover, at the later stages of viral infection, Th2 cells can also contribute to the IL-13 environment, impacting the resulting viral load and adaptive immune outcomes [3,21,22]. Interestingly, dramatically elevated IL-13 levels have been reported at the lung mucosae in SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals [23]. Therefore, we suspect that COVID-19 patients may display significant lung ILC2-derived IL-13 (although the role of ILC2s during SARS-CoV-2 infection is yet to be fully realized) [24,25]. Even though some IL-13 can be helpful during respiratory viral infection by aiding effective antibody differentiation [26,27], recruitment of different immune cells [28-30], and coordination of amphiregulin-dependent epithelium restoration [31], excessive production is damaging to airway homeostasis. Excessive IL-13 at the lung mucosae could be a key determinant of COVID-19-related hyper-inflammation [23]. Donlan et al. have recently shown that IL-13 levels are a powerful predictor of COVID-19 severity and the need for ventilation, independently of age, gender, and comorbidity [32]. This is unsurprising, given that many characteristics of fatal disease can be attributed to symptoms of dysregulated IL-13 [33]. Moreover, it is also noteworthy that the production of elevated Th2 cytokines, IL-4, and IL-13 is thought to be an inherent mechanism by which viruses evade the host immune system, promoting the induction of poor-quality cytotoxic T cell immunity [3,34-36].

It is well-established that IL-13 can effectively recruit inflammatory neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, and lymphocytes to the lung mucosae, resulting in elevated expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines [14,15,37-40]. Interestingly, patients with severe COVID-19 have shown to overexpress cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1-a, which can inadvertently promote overwhelming tissue damage [33,41,42]. The hyper-inflammatory phenotype and underlying cytokine storm is thought to be the primary cause of COVID-19-associated death, resulting in acute respiratory distress syndrome and subsequent multi-organ failure [43]. Collectively, these observations indicate that IL-13 may underpin inflammatory immune cell representations at the lung to drive cytokine storming in patients with COVID-19.

Further, IL-13 is well-known to have direct implications on lung tissue remodeling, airway obstruction, and acute/chronic lung damage in both allergy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [44]. Specifically, IL-13 facilitates airway smooth muscle proliferation, fibroblast proliferation, goblet cell hyperplasia, parenchymal inflammation, and collagen deposition [13,14,45-47], many of which have been observed in patients with fatal COVID-19 [33]. Thus, we suspect that IL-13 may be the upstream mediator of severe SARS-CoV-2 disease.

Moreover, IL-33 is a key upstream mediator of IL-13 at the lung mucosae and is thought to play a role in COVID-19 pathogenesis [48]. IL-33 is an alarmin produced by epithelial cells/alveolar macrophages to recruit and activate immune cells, particularly IL-33R+ lung ILC2s [49]. Interestingly, our recent studies have shown that transient sequestration of IL-33 at the lung mucosae using a viral vector expressing IL-33RBP (binding protein) does not impact ILC2-drived IL-13 expression. In contrast, IL-25RBP has a marked impact on ILC2-derived IL-13 [50]. This indicates a complex hierarchy between these cytokines. Notably, other studies have also shown that IL-33, IL-25, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin differentially modulate ILC2 activity, specifically in the context of tissue remodeling, allergy, and inflammation [51,52]. However, we propose that in the context of alleviating severe COVID-19, direct inhibition of IL-13 may yield better disease outcomes rather than targeting a particular upstream determinant of IL-13 expression.

In comparative respiratory conditions with similar molecular and immunological signatures, restricting IL-13 signaling has improved patient outcomes. For example, treatment with a monoclonal human anti-IL-4Rα antibody dupilumab (which inhibits both IL-13 and IL-4 signaling) has shown significant benefits in patients with otherwise uncontrollable asthma or severe dermatitis [53,54]. Interestingly, it has been proposed that such interventions could be unfavorable in treating COVID-19, in part due to the Th1/Th17 cytokines involved in hyperinflammation, where IL-13/IL-4 inhibition may further bias in immune activity [55]. However, our laboratory and others have demonstrated that IL-13 does not necessarily adhere to the classical Th1/Th2 immune paradigm, as exemplified by the broad profile of immune cells it modulates and/or recruits [3,14,20,48,56,57]. Importantly, Dupilumab, along with its favorable safety profile, is widely known to reduce airway inflammation (including Th1/Th17 cytokines) and improve global lung function (such as improve forced expiration volume) [53,58-60]. Similar findings have also been reported in asthmatics using Tralokinumab, which directly binds to and neutralizes IL-13. However, while Tralokinumab clearly improves spirometric outputs, limited benefit to quality of life has been reported [61,62]. Thus, at early stages of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection, IL-13 inhibition at the lung mucosae may help reduce COVID-19 disease severity/progression.

Alternatively, viral vectors have long been utilized as vehicles to express vaccine antigens, immunomodulators, cytokines/chemokines, and cytokine receptors [63,64]. We have studied the use of viral vectors that co-express vaccine antigens with either (1) mutant IL-4 lacking the signaling domain that can bind to and antagonize IL-4Rα to restrict the signaling of STAT6 or (2) IL-13Rα2 that sequesters excess IL-13 at the vaccination site to improve the quality of cytotoxic T cell immunity [20,22,27]. In the context of COVID-19, a viral vector-based approach to transiently inhibit excess IL-13 at the lung mucosae may help alleviate severe disease similarly to therapies using monoclonal antibodies. However, an attenuated viral vector could be a more attractive approach, with a single dose offering long lasting (~3 days) benefit, while still being safe and providing a highly localized/targeted response. However, in this context, selecting a viral vector that induces low IL-13 would be of great importance, as vectors themselves can promote the induction of ILC2-derived IL-13 and DC activity at the lung mucosae [11,50,57]

In conclusion, knowing that IL-13 is a powerful indicator of COVID-19 severity [14,32], interventions that directly inhibit IL-13 activity at the lung mucosae may prove useful in preventing or reducing disease progression. Since safe and effective IL-13 inhibiting drugs/therapies are already available (such as allergy/asthma treatments and recombinant viral vectors) [53,58], their repurposing could be a highly cost-effective solution in alleviating SARS-CoV-2-associated pathology. This warrants investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Development grant # APP1136351 awarded to CR.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, et al. Interleukin-13:Central Mediator of Allergic Asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–61. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Passalacqua G, Mincarini M, Colombo D, Troisi G, Ferrari M, Bagnasco D, et al. IL-13 and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis:Possible Links and New Therapeutic Strategies. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ranasinghe C, Turner SJ, McArthur C, Sutherland DB, Kim JH, Doherty PC, et al. Mucosal HIV-1 Pox Virus Prime-Boost Immunization Induces High-Avidity CD8+T Cells with Regime-Dependent Cytokine/Granzyme B Profiles. J Immunol. 2007;178:2370–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Howell MD, Gallo RL, Boguniewicz M, Jones JF, Wong C, Streib JE, et al. Cytokine Milieu of Atopic Dermatitis Skin Subverts the Innate Immune Response to Vaccinia virus. Immunity. 2006;24:341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ranasinghe C, Trivedi S, Wijesundara DK, Jackson RJ. IL-4 and IL-13 Receptors:Roles in Immunity and Powerful Vaccine Adjuvants. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014;25:437–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Foster PS, Maltby S, Rosenberg HF, Tay HL, Hogan SP, Collison AM, et al. Modeling T(H) 2 Responses and Airway Inflammation to Understand Fundamental Mechanisms Regulating the Pathogenesis of Asthma. Immunol Rev. 2017;278:20–40. doi: 10.1111/imr.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wongpiyabovorn J, Suto H, Ushio H, Izuhara K, Mitsuishi K, Ikeda S, et al. Up-Regulation of Interleukin-13 Receptor Alpha1 on Human Keratinocytes in the Skin of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2003;33:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(03)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chang YJ, Kim HY, Albacker LA, Baumgarth N, McKenzie AN, Smith DE, et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells Mediate Influenza-Induced Airway Hyper-Reactivity Independently of Adaptive Immunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:631–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mindt BC, Fritz JH, Duerr CU. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Pulmonary Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:840. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li Z, Jackson RJ, Ranasinghe C. Vaccination Route Can Significantly Alter the Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets:A Feedback Between IL-13 and IFN-γ. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:10. doi: 10.1038/s41541-018-0048-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Roy S, Liu HY, Jaeson MI, Deimel LP, Ranasinghe C. Unique IL-13Ra2/STAT3 Mediated IL-13 Regulation Detected in Lung Conventional Dendritic Cells, 24 h Post Viral Vector Vaccination. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57815-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, et al. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells are Critical for the Initiation of Adaptive T Helper 2 Cell-Mediated Allergic Lung Inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, Chen Q, Geba GP, Wang J, et al. Pulmonary Expression of Interleukin-13 Causes Inflammation, Mucus Hypersecretion, Subepithelial Fibrosis, Physiologic Abnormalities, and Eotaxin Production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:779–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fulkerson PC, Fischetti CA, Hassman LM, Nikolaidis NM, Rothenberg ME. Persistent Effects Induced by IL-13 in the Lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:337–46. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0474OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhu Z, Ma B, Zheng T, Homer RJ, Lee CG, Charo IF, et al. IL-13-Induced Chemokine Responses in the Lung:Role of CCR2 in the Pathogenesis of IL-13-Induced Inflammation and Remodeling. J Immunol. 2002;168:2953–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gudmundsson KO, Sigurjonsson OE, Gudmundsson S, Goldblatt D, Weemaes CM, Haraldsson A. Increased Expression of Interleukin-13 but not Interleukin-4 in CD4+Cells from Patients with the Hyper-IgE Syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:532–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ingram JL, Kraft M. IL-13 in Asthma and Allergic Disease:Asthma Phenotypes and Targeted Therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:824–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Newman JP, Wang GY, Arima K, Guan SP, Waters MR, Cavenee WK, et al. Interleukin-13 Receptor Alpha 2 Cooperates with EGFRvIII Signaling to Promote Glioblastoma Multiforme. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1913. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01392-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kioi M, Kawakami M, Shimamura T, Husain SR, Puri RK. Interleukin-13 Receptor Alpha 2 Chain:A Potential Biomarker and Molecular Target for Ovarian Cancer Therapy. Cancer. 2006;107:1407–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ranasinghe C, Trivedi S, Stambas J, Jackson RJ. Unique IL-13Ra2-Based HIV-1 Vaccine Strategy to Enhance Mucosal Immunity, CD8(+) T-Cell Avidity and Protective Immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:1068–80. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bao K, Reinhardt RL. The Differential Expression of IL-4 and IL-13 and Its Impact on Type-2 Immunity. Cytokine. 2015;75:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Khanna M, Jackson RJ, Alcantara S, Amarasena TH, Li Z, Kelleher AD, et al. Mucosal and Systemic SIV-Specific Cytotoxic CD4+T Cell Hierarchy in Protection Following Intranasal/Intramuscular Recombinant Pox-Viral Vaccination of Pigtail Macaques. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5661. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41506-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yuki K, Fujiogi M, Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 Pathophysiology:A Review. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108427. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Radzikowska U, Ding M, Tan G, Zhakparov D, Peng Y, Wawrzyniak P, et al. Distribution of ACE2, CD147, CD26 and other SARS-CoV-2 Associated Molecules in Tissues and Immune Cells in Health and in Asthma, COPD, Obesity, Hypertension, and COVID-19 Risk Factors. Allergy. 2020;75:2829–45. doi: 10.1111/all.14429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rahaman SO, Sharma P, Harbor PC, Vogelbaum MA, Haque SJ, Sharma P, et al. IL-13Ra2, a Decoy Receptor for IL-13 Acts as an Inhibitor of IL-4-Dependent Signal Transduction in Glioblastoma Cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1103–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jackson RJ, Worley M, Trivedi S, Ranasinghe C. Novel HIV IL-4R Antagonist Vaccine Strategy Can Induce Both High Avidity CD8 T and B Cell Immunity with Greater Protective Efficacy. Vaccine. 2014;32:5703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Abt MC, Alenghat T, Ziegler CG, Doering TA, et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Lung-Tissue Homeostasis after Infection With Influenza Virus. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1045–54. doi: 10.1031/ni.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Karta MR, Broide DH, Doherty TA. Insights into Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in Human Airway Disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:8. doi: 10.1007/s11882-015-0581-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ngoc PL, Gold DR, Tzianabos AO, Weiss ST, Celedon JC. Cytokines, Allergy, and Asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:161–6. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000162309.97480.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jeffery HC, McDowell P, Lutz P, Wawman RE, Roberts S, Bagnall C, et al. Human Intrahepatic ILC2 are IL-13 Positive Amphiregulinpositive and their Frequency Correlates with Model of End Stage Liver Disease Score. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Donlan AN, Young M, Petri WA, Abhyankar M. IL-13 Predicts the Need for Mechanical Ventilation in COVID-19 Patients, medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bradley BT, Maioli H, Johnston R, Chaudhry I, Fink SL, Xu H, et al. Histopathology and Ultrastructural Findings of Fatal COVID-19 Infections in Washington State:A Case Series. Lancet. 2020;396:320–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maggi E, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Annunziato F, Manetti R, Piccinni MP, et al. Th2-Like CD8+T Cells Showing B Cell Helper Function and Reduced Cytolytic Activity in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection. J Exp Med. 1994;180:489–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kienzle N, Olver S, Buttigieg K, Groves P, Janas ML, Baz A, et al. Progressive Differentiation and Commitment of CD8+T Cells to a Poorly Cytolytic CD8low Phenotype in the Presence of IL-4. J Immunol. 2005;174:2021–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ranasinghe C, Ramshaw IA. Immunisation Route-Dependent Expression of IL-4/IL-13 Can Modulate HIV-Specific CD8(+) CTL Avidity. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1819–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Borthwick LA, Barron L, Hart KM, Vannella KM, Thompson RW, Oland S, et al. Macrophages are Critical to the Maintenance of IL-13-Dependent Lung Inflammation and Fibrosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:38–55. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bochner BS, Klunk DA, Sterbinsky SA, Coffman RL, Schleimer RP. IL-13 Selectively Induces Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Expression in Human Endothelial Cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:799–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kong DH, Kim YK, Kim MR, Jang JH, Lee S. Emerging Roles of Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in Immunological Disorders and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1057. doi: 10.3390/ijms19041057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Neveu WA, Allard JL, Raymond DM, Bourassa LM, Burns SM, Bunn JY, et al. Elevation of IL-6 in the Allergic Asthmatic Airway is Independent of Inflammation but Associates with Loss of Central Airway Function. Respir Res. 2010;11:28. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19:Consider Cytokine Storm Syndromes and Immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mason RJ. Pathogenesis of COVID-19 from a Cell Biology Perspective. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000607. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00607-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ragab D, Eldin HS, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 Cytokine Storm;What We Know So Far. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Grubek-Jaworska H, Paplińska M, Hermanowicz-Salamon J, Białek-Gosk K, Dąbrowska M, Grabczak E, et al. IL-6 and IL-13 in Induced Sputum of COPD and Asthma Patients:Correlation with Respiratory Tests. Respiration. 2012;84:101–7. doi: 10.1159/000334900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fukushi J, Ono M, Morikawa W, Iwamoto Y, Kuwano M. The Activity of Soluble VCAM-1 in Angiogenesis Stimulated by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 2000;165:2818–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Corren J. Role of Interleukin-13 in Asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:415–20. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kondo Y, Yoshimoto T, Yasuda K, Futatsugi-Yumikura S, Morimoto M, Hayashi N, et al. Administration of IL-33 Induces Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Goblet Cell Hyperplasia in the Lungs in the Absence of Adaptive Immune System. Int Immunol. 2008;20:791–800. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zizzo G, Cohen PL. Imperfect Storm:Is Interleukin-33 the Achilles Heel of COVID-19? Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e779–90. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30340-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes Represent a New Innate Effector Leukocyte that Mediates Type-2 Immunity. Nature. 2010;464:1367–70. doi: 10.1038/nature08900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li Z, Jackson RJ, Ranasinghe C. A Hierarchical Role of IL-25 in ILC Development and Function at the Lung Mucosae Following Viral-Vector Vaccination. Vaccine X. 2019;2:100035. doi: 10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Camelo A, Rosignoli G, Ohne Y, Stewart RA, Overed-Sayer C, Sleeman MA, et al. IL-33, IL-25, and TSLP Induce a Distinct Phenotypic and Activation Profile in Human Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells. Blood Adv. 2017;1:577–89. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016002352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Han M, Rajput C, Hong JY, Lei J, Hinde JL, Wu Q, et al. The Innate Cytokines IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP Cooperate in the Induction of Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Expansion and Mucous Metaplasia in Rhinovirus-Infected Immature Mice. J Immunol. 2017;199:1308–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2486–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, Papp KA. Dupilumab:A Review of Its Use in the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:S28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Patruno C, Stingeni L, Fabbrocini G, Hansel K, Napolitano M. Dupilumab and COVID-19:What Should We Expect? Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13502. doi: 10.1111/dth.13502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hamid MA, Jackson RJ, Roy S, Khanna M, Ranasinghe C. Unexpected Involvement of IL-13 Signalling via a STAT6 Independent Mechanism During Murine IgG2a Development Following Viral Vaccination. Eur J Immunol. 2018;48:1153–63. doi: 10.1002/eji.201747463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Roy S, Jaeson MI, Li Z, Mahboob S, Jackson RJ, Grubor-Bauk B, et al. Viral Vector and Route of Administration Determine the ILC and DC Profiles Responsible for Downstream Vaccine-Specific Immune Outcomes. Vaccine. 2019;37:1266–76. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, Maspero JF, Castro M, Sher L, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Glucocorticoid-Dependent Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2475–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wenzel S, Ford L, Pearlman D, Spector S, Sher L, Skobieranda F, et al. Dupilumab in Persistent Asthma with Elevated Eosinophil Levels. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2455–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, Maspero J, Wang L, Zhang B, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Adults with Uncontrolled Persistent Asthma Despite use of Medium-to-High-Dose Inhaled Corticosteroids Plus a Long-Acting b2 Agonist:A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Pivotal Phase 2b Dose-Ranging Trial. Lancet. 2016;388:31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Parker JM, Glaspole IN, Lancaster LH, Haddad TJ, She D, Roseti SL, et al. A Phase 2 Randomized Controlled Study of Tralokinumab in Subjects with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:94–103. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201704-0784OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Zhang Y, Cheng J, Li Y, He R, Pan P, Su X, et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Anti-IL-13 Treatment with Tralokinumab (CAT-354) in Moderate to Severe Asthma:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2661–71. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ, Karupiah G, Rolph MS, Mahalingam S, Ruby JC. Cytokines and Immunity to Viral Infections. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:119–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Leong KH, Ramsay AJ, Boyle DB, Ramshaw IA. Selective Induction of Immune Responses by Cytokines Coexpressed in Recombinant Fowlpox Virus. J Virol. 1994;68:8125–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8125-8130.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]