Graphical abstract

Keywords: Mixed convection, Thermophoresis and Brownian motion, Hybrid nanofluid, Two-phase approach, Wavy heater, Localized solid block

Highlights

-

•

Flow, heat, and mass transfer of hybrid nanofluids in a wavy chamber were addressed.

-

•

A two-phase approach, including the Brownian motion and thermophoresis forces, was introduced.

-

•

The drift flux of composite hybrid nanoparticles was computed.

-

•

The concentration distribution of composite nanoparticles was investigated.

-

•

The location of the solid block and undulation of surfaces are investigated.

Abstract

Introduction:

Mixed convection flow and heat transfer within various cavities including lid-driven walls has many engineering applications. Investigation of such a problem is important in enhancing the performance of the cooling of electric, electronic and nuclear devices and controlling the fluid flow and heat exchange of the solar thermal operations and thermal storage.

Objectives:

The main aim of this fundamental investigation is to examine the influence of a two-phase hybrid nanofluid approach on mixed convection characteristics including the consequences of varying Richardson number, number of oscillations, nanoparticle volume fraction, and dimensionless length and dimensionless position of the solid obstacle.

Methods:

The migration of composite hybrid nanoparticles due to the nano-scale forces of the Brownian motion and thermophoresis was taken into account. There is an inner block near the middle of the enclosure, which contributes toward the flow, heat, and mass transfer. The top lid cover wall of the enclosure is allowed to move which induces a mixed convection flow. The impact of the migration of hybrid nanoparticles with regard to heat transfer is also conveyed in the conservation of energy. The governing equations are molded into the non-dimensional pattern and then explained using the finite element technique. The effect of various non-dimensional parameters such as the volume fraction of nanoparticles, the wave number of walls, and the Richardson number on the heat transfer and the concentration distribution of nanoparticles are examined. Various case studies for Al2O3-Cu/water hybrid nanofluids are performed.

Results:

The results reveal that the temperature gradient could induce a notable concentration variation in the enclosure.

Conclusion:

The location of the solid block and undulation of surfaces are valuable in the control of the heat transfer and the concentration distribution of the composite nanoparticles.

Nomenclature

amplitude

dimensionless solid block position,

specific heat capacity

dimensionless solid block length,

diameter of the base fluid molecule

diameter of the nanoparticle

Brownian diffusion coefficient

reference Brownian diffusion coefficient

thermophoretic diffusivity coefficient

reference thermophoretic diffusion coefficient

dimensionless width of the heat source,

thermal conductivity

circular cylinder to nanofluid thermal conductivity ratio,

width and height of the square cavity

Lewis number

number of undulations

ratio of Brownian to thermophoretic diffusivity

average Nusselt number

Prandtl number

Richardson number

Reynolds number

Brownian motion Reynolds number

Schmidt number

temperature

reference temperature (310 K)

freezing point of the base fluid (273.15 K)

velocity vector

normalized velocity vector

Brownian velocity of the nanoparticle

- , & ,

space coordinates & dimensionless space coordinates

Greek symbols

thermal diffusivity

inclination angle of magnetic field

thermal expansion coefficient

normalized temperature parameter

dimensionless temperature

dynamic viscosity

kinematic viscosity

density

solid volume fraction

normalized solid volume fraction

average solid volume fraction

Subscript

bottom

cold

base fluid

hot

hybrid nanofluid

solid nanoparticles

Introduction

The study of mixed convection flow and heat transfer within various cavities including lid-driven walls has attracted concern due to its application in a comprehensive variety of engineering fields like nuclear reactors, electronic devices and solar power [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Mixed convection includes the forced convection which results in the passage of the surface(s) and the natural convection which occurs as a result of the difference in temperature. This coupling within the buoyancy force and the shear force makes it more complicated. Oztop et al. [9] examined laminar mixed convection flow considering the magnetic force into a lid-driven enclosure heated at the corner. Their conclusions indicated that the magnetic domain owns a significant influence toward controlling the heat and fluid flow. In contrast, dimensions of the heater have a vital force on the natural convection dominant regime. Sheikholeslami and Chamkha [10] investigated the importance of a variable magnetic domain toward the characteristics of mixed convection flow within the lid-driven enclosure having a sinusoidal hot surface. It did conclude that the rate of heat transfer enhances by growing Reynolds number, nanoparticle volume fraction, and magnetic number, whereas the converse does obtain for the Hartmann number. Azizul et al. [11] numerically examined mixed convection by heatline visualization technique inside a wavy bottom enclosure equipped by a solid central block. The results showed that natural convection was dominated for essential rates of Grahsof number achieving the maximum heat transfer rate in the system. Karbasifar et al. [12] examined numerically mixed convection regarding Al2O3-water nanofluids within an enclosure including hot elliptical cylinder located at the centre. They described that the increment in the average heat transfer relies upon the fluid velocity, volume fraction and cavity angle. More interesting analyses on convection heat transfer in an enclosure including the detached obstacle of different configurations (square, circular, and triangular), can be found in the referenced papers [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

Computational fluid dynamic (CFD) predictions of the convective heat transfer, fluid flow and temperature distributions can be achieved using two main paths. These are homogenous single-phase and two-phase approaches [23]. The former depends on the continuous phase assumption and considers that nanoparticles and the working liquid remain in thermal equilibrium among negligible slip velocity within them. The assumption of the two-phase path considers that the value of the corresponding velocity among the nanoparticles and the fluid phase may not equal to zero where different advanced methods manage the governing equations. The two-phase approach ought widely adopted for simulating both natural convection such as in references [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31] and mixed convection such as in references [32], [33], [34], [35] in nanofluids. Wen and Ding [36] experimentally concluded that the two-phase nanofluid path does found to be further accurate due to the possible variations in the slip velocity within the nanoparticles and the working liquid. Buongiorno [37] formed a non-homogeneous equilibrium rule, including the effect of thermophoresis and Brownian motion as the two significant slip mechanisms in particular nanofluid flow. The author introduced seven slip mechanisms between the working liquid and nanoparticles by developing a non-homogeneous two-component equation which shows the significance of Brownian motion and thermophoresis. Darzi et al. [38] presented 2D and 3D numerical simulations to show the impact of Cu nanofluid on mixed convection heat transfer within the lid-driven hollow utilizing the two-phase mixture form. It was concluded that the use of fines does not raise the heat transfer toward moderate and low Richardson numbers because of occurring the flow blockage within the corners of the used fins. Motlagh and Soltanipour [39] and Esfandiary et al. [40] examined free convection heat transfer inside a square hollow including nanofluids adopting the two-phase model. Their findings noted that the rule of heat transfer increased by increasing the concentration of rated nanoparticles.

Recently, several researchers have concentrated toward the application of combined or hybrid nanofluid as an innovative category of nanofluids engineered through dispersing two types or more of nanoparticles, including metallic and non-metallic nanoparticles, in ordinary liquids. Metallic nanoparticles, like Cu, Ag, Au, and Al, have high values of thermal conductivities, but they have limitations in terms of their poor stabilities and significant reactivity. The use of non-metallic nanoparticles like MgO, CuO, Al2O3, and Fe3O4 shows low thermal conductivities with many beneficial properties compared to the metallic, like excellent stability and chemical inertness [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]. Therefore, it is expected that the combined of metallic with non-metallic nanosized particles leads to improve the thermophysical features of the hybrid nanofluid with achieving the accepted stability. However, this also depends on the suitable selection of these combined nanoparticle materials. Suresh et al. [52] achieved the highest improvement level of 13.56% toward the heat transfer rate by employing Al2O3-Cu hybrid nanofluid. Tayebi and Chamkha [53] analysed the natural convection and entropy generation under the magnetic field inside a square cavity containing a hollow cylinder loaded by Al2O3-Cu/water hybrid nanofluid. The effective viscosity and thermal conductivity occurred defined using Corcione correlations regarding the Brownian motion of nanoparticles. The outcomes determined that inserting a hollow conducting cylinder can significantly change the flow characteristic and thermal patterns as well as irreversibilities within the enclosure. The impact of using Al2O3 nanoparticles and Al2O3-Cu hybrid nanoparticles suspended in water on mixed convection in a cavity equipped via heated oscillating cylinder did numerically questioned by Mehryan et al. [54]. It was determined that the use of the considered nanoparticles confirms improvement in the heat transfer rate for the cases of low Rayleigh number. Ismael et al. [55] examined the entropy generation and mixed convection of hybrid nanofluids within a lid-driven cavity numerically. The outcomes confirmed that the use of hybrid nanofluid improves the economical features by decreasing the amount of significant thermal conductivity nanoparticles. The literature shows significant gaps in the knowledge of using the two-phase hybrid nanofluid approach. In addition, there is a need for further understanding of the effect of the wavy walls on heat transfer and fluid flow. The current research makes progress towards discussing these significant gaps together with the important effect of using an internal localized solid block through the mixed convection. Additional published studies on free convection heat transfer using phase change of hybrid nanofluids can be found into references [56], [57], [58], [59].

In a very recent study, Goudarzi et al. [60] modeled the two-phase flow and heat transfer of hybrid nanofluids in an enclosure. They examined the free convection heat transfer of Ag–MgO nanoparticles in the water by taking into account the influence of the thermophoresis and Brownian motion effects. These authors assumed that the Ag and MgO nanoparticles are added into the water in distinct phases, and the particles are not in physical contact. So, they considered independent concentration equations for each of Ag and MgO nanoparticles. This approach can be applied for hybrid nanofluids with separate nanoparticles. However, most of the hybrid nanofluids indeed are made of composite nanoparticles [61], [62]. Hence, the two types of nanoparticles bond to each other in the host fluid in the form of a composite nanoparticle and migrate simultaneously. As a result, there will be only one concentration equation for the composite particles (hybrid nanoparticles), but the thermophoresis and Brownian motion forces should be computed for the composite nanoparticle. The present study aims to model the two-phase convection heat transfer of composite hybrid nanofluids.

Based upon the literature survey above and the authors’ awareness, no such work has been reported to deal with mixed convection inside wavy lid-driven enclosures having a localized solid square block and using a two-phase hybrid nanofluid approach. Thus, the main aim of this fundamental investigation exists to examine the influence of a two-phase hybrid nanofluid approach on mixed convection characteristics including the consequences of varying Richardson number, number of oscillations, nanoparticle volume fraction, and dimensionless length and dimensionless position of the solid obstacle. This investigation can contribute to enhancing the performance of the cooling of electric, electronic and nuclear devices and to controlling the fluid flow and heat exchange of the solar thermal operations and thermal storage.

Mathematical formulation

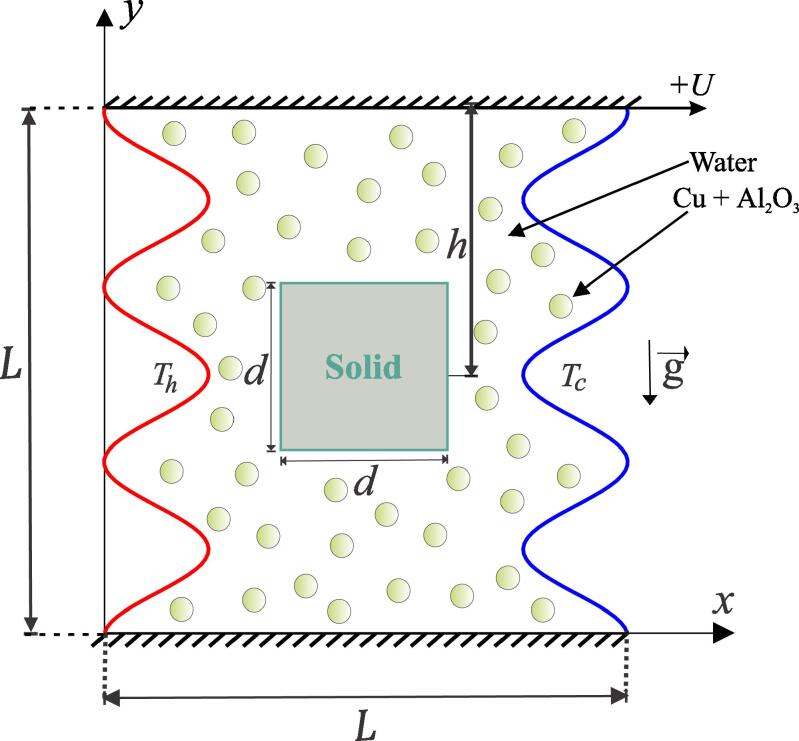

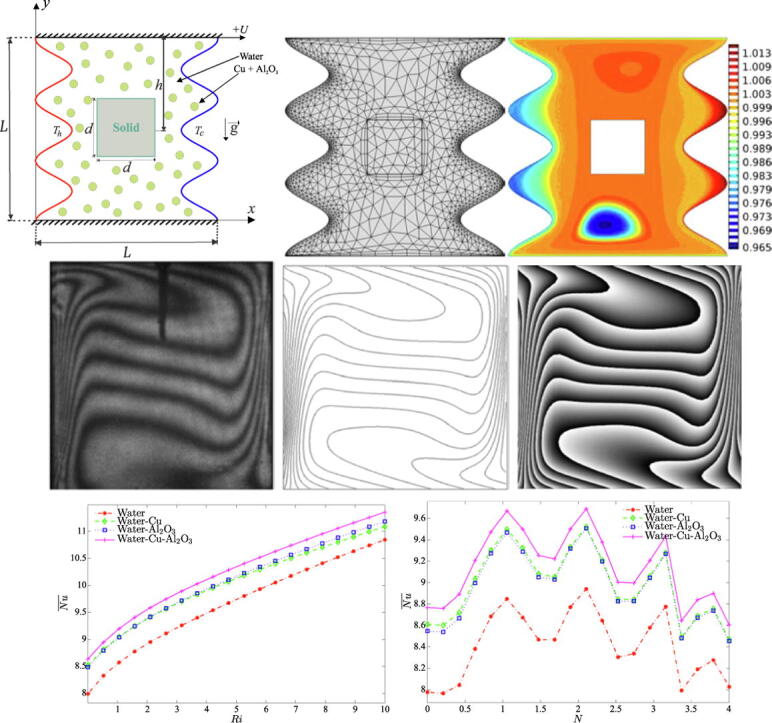

The mixed convective heat transfer problem of hybrid nanoliquid flowing into wavy-walled cavities having length L and containing square solid block with length d and horizontal position h is considered, as outlined in Fig. 1. The left wavy isothermal heater does maintained by the xed temperature (). The wavy sidewall of the enclosure having an isothermal cold temperature (). The top moving surface, as well as the bottom surface, remain well insulated. All of the wavy cavity surfaces are impermeable including no-slip condition, and the uid inside the hollow remains water-based hybrid nanofluid containing Cu-Al2O3 nanoparticles, and the Boussinesq approximation continues appropriate. Examining the assumptions mentioned above, the continuity, momentum and energy equations regarding the laminar and steady convection are as the following [32], [63]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The heat equation concerning the solid block is:

| (5) |

Based on the two-phase approach, the nanoparticles mass flux () will be formulated as:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

The hybrid nanofluids sufficient physical properties are implemented in the following scheme:

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation regarding the physical design, geometrical features and the coordinate system.

Hybrid nanofluid heat capacitance given is

| (9) |

Hybrid nanofluid density is given as

| (10) |

Hybrid nanofluid buoyancy coefficient with be defined as:

| (11) |

The dynamic viscosity ratio of nanofluids occurred obtained by Corcione [64] as:

| (12) |

and the thermal conductivity ratio of nanofluids obtained also by Corcione [64] as:

| (13) |

Using on these two models, we will define the dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity ratios concerning water-Cu-Al2O3 hybrid nanofluids toward 33 and 29 nm particles with the following form [65]:

| (14) |

| (15) |

where of the hybrid nanofluid is defined as:

| (16) |

Here nm is the mean path of the liquid particles, determines the Boltzmann number and defines the molecular diameter of the used liquid (water) as the following form [64]:

| (17) |

Presently we shall propose the following non-dimensional variables:

| (18) |

Resulting toward the following dimensionless governing equations:

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

where

| (24) |

The dimensionless boundary conditions of Eqs. (19), (20), (21), (22) are:

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

The local Nusselt number (Nu) does determine toward the hot wavy surface as:

| (29) |

where W the total length of the hot wavy source. The average Nusselt number evaluated on the heated wavy surface which is defined as follows:

| (30) |

Numerical Method and Validation

The dimensionless form of the governing equations Eqs. (19), (20), (21), (22) controlled by the dimensionless boundary conditions Eqs. (25), (26), (27), (28) are solved by the Galerkin weighted residual finite element method. First, we transfer the momentum equations in Eq. (20) to the Cartesian X and Y-coordinates as the following:

The momentum equation in the X-direction:

| (31) |

The momentum equation in the Y-direction:

| (32) |

The Finite Element Method (FEM) is used for determining the governing equations. Employing the FEM toward the momentum Eqs. (31), (32) directs into the following rule:

At first, the penalty FEM is implemented to eliminate the pressure (P), including the penalty parameter () as:

which consequently generates the momentum equations in X and Y:

Regarding the FEM, the governing equations are formulated toward the weak (or weighted-integral) formulation. Therefore, the resulting weak formulations concerning equations across the wavy region remain accomplished:

Next, the following basis extensions are used toward the variables ranges:

| (33) |

Then again, the residual pattern of equations is computed by integrating the weak appearance of equations across the discrete region:

whereas the relative index denotes by the superscript k, subscripts regarding describe the residual and node number, respectively. Here, m determines the iteration number.

Furthermore, integrals are completed through the second order Gaussian quadrature. The Newton–Raphson iteration algorithm is employed for iteratively determining the residual equations by the following closing form of all field variables:

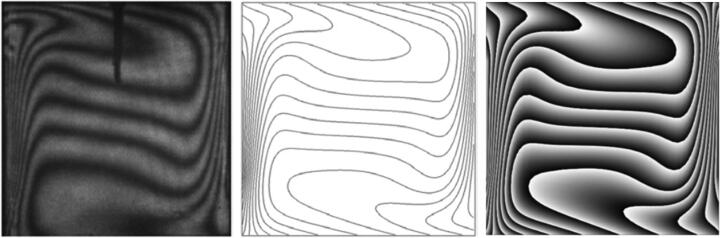

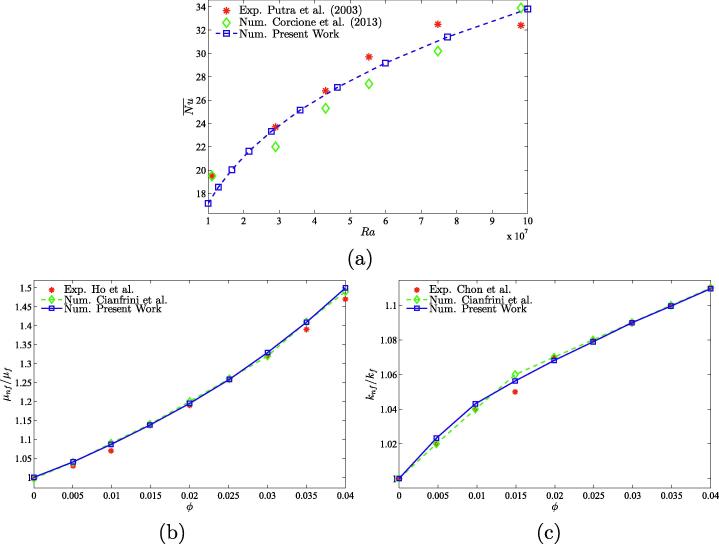

Toward the aim of approving the existing numerical data, comparisons are made among the simulated data and the experimental and numerical achievements of Paroncini et al. [66] concerning the free convection case inside a square enclosure activated from sides, as exhibited in Fig. 2. Fig. 3(a) displays a comparison among the current outcomes and the experimental arrangements of Putra et al. [67] and the numerical result of Corcione et al. [68] using Buongiorno’s model and for various Rayleigh numbers at and . While the models of the thermal conductivity and the dynamic viscosity remain confirmed by a comparison among the experimental data in Fig. 3, Fig. 3(c). Considering such findings which perform significant trust toward the accuracy of the existing numerical approach.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of isotherms between (left) experimental outcomes of Paroncini et al. [66], (middle) numerical work of Paroncini et al. [66], and (right) the current work; and .

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of (a) the average Nusselt number with the current outcomes, the experimental outcomes of Putra et al. [67] and the numerical outcomes of Corcione et al. [68] toward several amounts of Rayleigh number at and and , (b) the thermal conductivity ratio with Chon et al. [69] and Cianfrini et al. [70]; and (c) the dynamic viscosity ratio with the experimental and numerical outcomes of Ho et al. [71] and Cianfrini et al. [70].

Results and Discussion

The current section displays numerical outcomes concerning the streamlines, isotherms and nanoparticle distribution among various values of the Richardson number (), nanoparticle volume fraction (), number of undulations (), dimensionless length of the solid block () and the dimensionless position of the solid block () where additional parameters remain fixed as and , respectively. The thermophysical characteristics of the base fluid (water), Cu nanoparticles and Al2O3 nanoparticles phases are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermo-physical properties of water, Cu nanoparticles and Al2O3 nanoparticles at K [72].

| Physical properties | Fluid phase (water) | Cu | Al2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.628 | 400 | 40 | |

| 695 | – | – | |

| 993 | 8933 | 3970 | |

| 4178 | 385 | 765 | |

| 36.2 | 1.67 | 0.85 | |

| 0.385 | 29 | 33 |

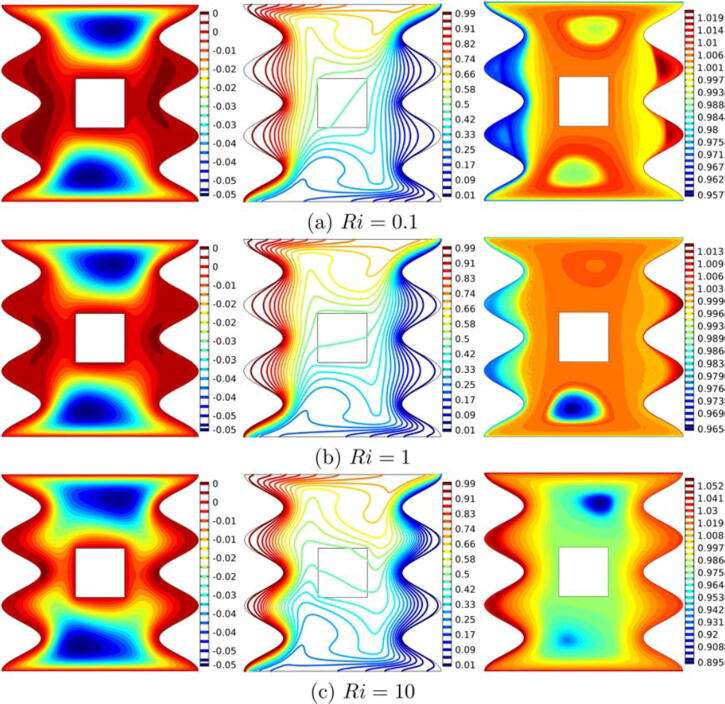

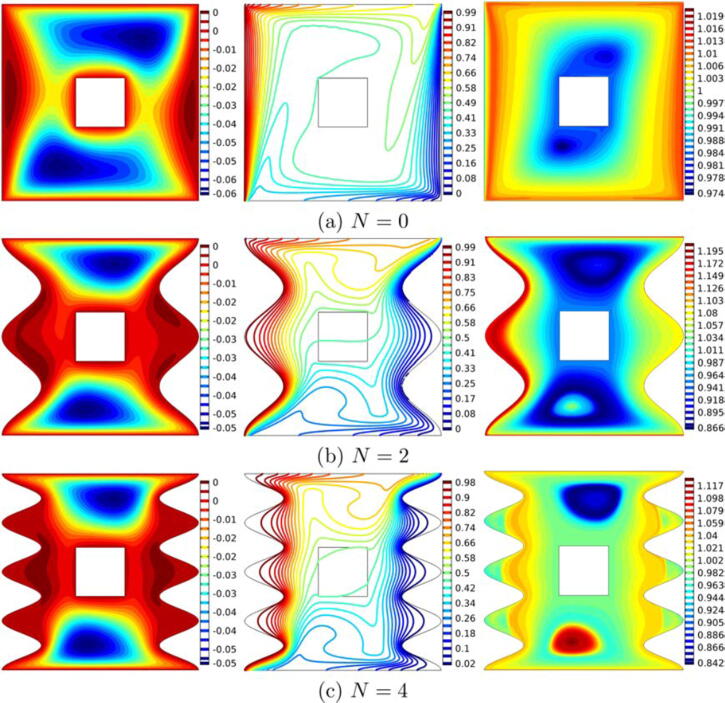

Fig. 4 presents the hybrid nanofluid flow fields, which are visualized by the streamlines (left), the thermal fields, which are visualized by the dimensionless temperature isolines (middle), and the nanoparticle distribution (right) for various amounts of the Richardson number when and . The nanofluid flow structure portrays a formation of two main clockwise vortices near the adiabatic horizontal walls. The co-direction of the moving wall (shear-driven forces) and buoyancy forces helps such behavior to occur. The side wavy walls alter the form of the vortices. Flow close the block show high-velocity flow near to the top and bottom borders of the block. A low Richardson number depicts an appearance of secondary vortices in the left and right of the enclosure between the active walls and the solid body due to weak buoyancy forces. The isotherms lines show the growth of thermal boundary zones adjacent to the active vertical surfaces. The layer continues to rise inside the wavy troughs, while it groups at the crests. We also notice the development of a down-going plume-liken at the upper right moving wall and up-going one at the lower wall reflecting the behavior of heat transport inside the cavity. Increasing the Richardson number, by prevailing the buoyancy forces over the inertia forces, results in the increase of the main rotating vortices and the suppression of the secondary vortices with an important augmentation of the velocity gradients near the block and the wavy walls. Also, the isotherms become more irregular and horizontal. This denotes that free convection is predominant. The nanoparticles distribution displayed in Fig. 4 reports an appearance of nanoparticle concentration zones in the top, and the bottom portion of the enclosure which describes the particles transport directions in these areas due to the Brownian effects. Besides, the less intensive flow within the cavity, at low Ri, improves the thermophoresis effects, and therefore, a high concentration of nanoparticles is observed near the wavy cold wall. An increase in the Richardson results in a higher convective motion, and the circulating flow manages more nanoparticles, and thus, less concentration of nanoparticles occurs toward the cavity core.

Fig. 4.

Streamlines (left), isotherms (middle), and nanoparticle distribution (right) with Richardson number (Ri) for hybrid nanofluid, and .

We examine in Fig. 5 the effect of the undulations number of the active surfaces of the cavity on the flow, temperature, and hybrid nanoparticles isoconcentration patterns when and . The isothermal contours reflect a large temperature gradient on the flat walls (Fig. 5)) and on the crests of the wavy surfaces (Fig. 5(b and c)), with a wider zone for the first case, which result in a large local transmission rate in these areas. We note a diminution in the deterioration of the isotherms within the cavity by increasing the number of undulations which determines the weakness of the convective heat transport between the active walls. It was also found that imposing undulations toward the vertical active surfaces of the cavity tends to reduce the flow strength inside the cavity. The flow cells move away from the solid block toward the horizontal walls. The nanoparticles tend to be accumulated at the bottom of the cavity by raising the value of N.

Fig. 5.

Streamlines (left), isotherms (middle), and nanoparticle distribution (right) with number of oscillations (N) for hybrid nanofluid, and .

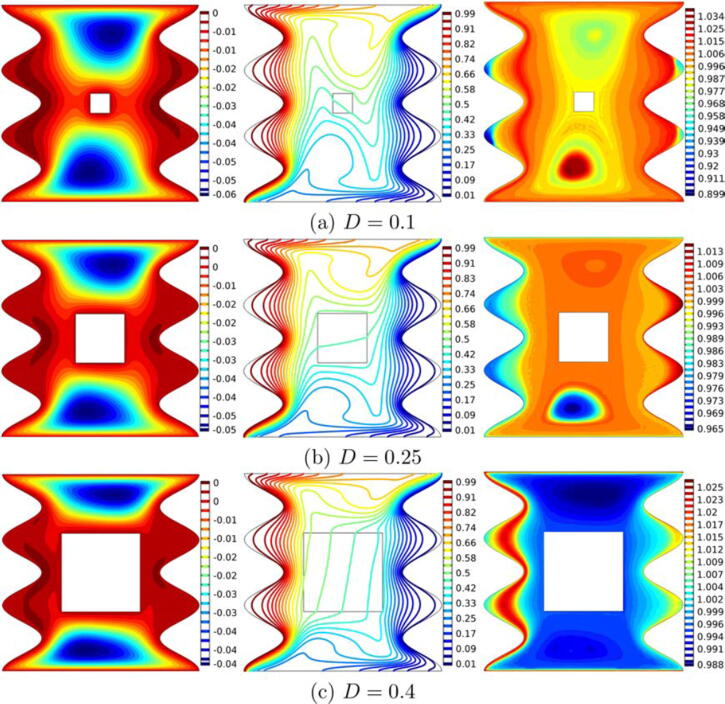

Fig. 6 portrays that inserting a large centered conducting block suppresses the convection flow within the cavity by reducing the flow area of the hybrid nanofluid and also limiting the influence concerning the shear force induced through the moving adiabatic wall. As a result, the isotherms reveal less deterioration. Concurrently, it is seen from the nanoparticle distribution contours that the nanoparticles prefer to be distributed close to the wavy walls at a higher value of D. This is because the thermal conduction mechanism enhances the thermophoresis effects.

Fig. 6.

Streamlines (left), isotherms (middle), and nanoparticle distribution (right) with dimensionless length of the solid block (D) for hybrid nanofluid, and .

Fig. 7 explores the effect of the relative position, up and down, of the solid body on streamlines and isotherms as well as the hybrid nanoparticle distribution contours when and . As seen from the figure, moving the conductive body downward (decreasing H) leads to a more free space in the upper part of the cavity for nanofluid flow and thermal plume development. As a result, one can nd a significant concentration of nanoparticles area there, due mainly to the thermophoretic effects inside the thermal plume and the shear effect movements. Moving the conductive body upward limits the impact from the shear force required with the upper moving wall, which is reflected at the concentration of nanoparticles inside the cavity as they dispersed throughout the cavity except for the bottom side (due to the effect of circulating zone which pushes the nanoparticles away) and near the cold wavy wall (due to thermophoretic impacts).

Fig. 7.

Streamlines (left), isotherms (middle), and nanoparticle distribution (right) with dimensionless position of the solid block (H) for hybrid nanofluid, and .

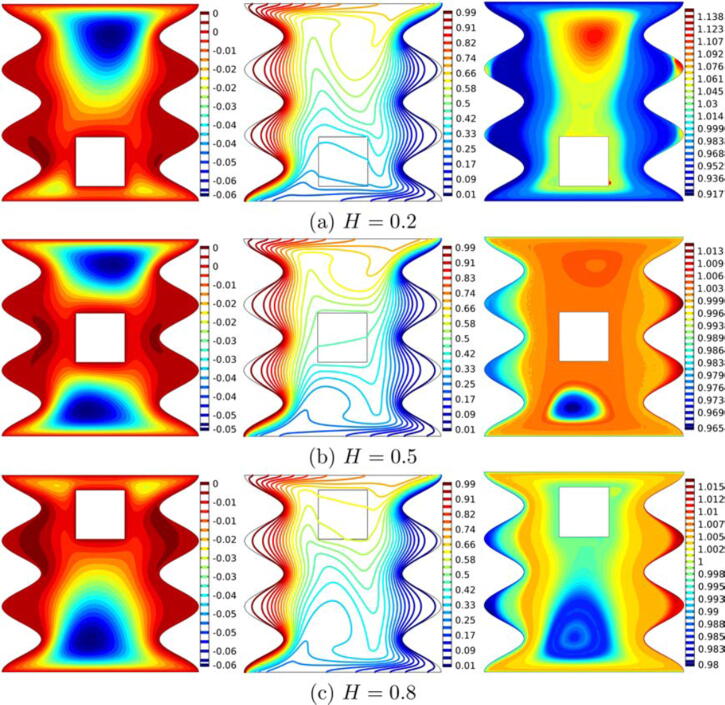

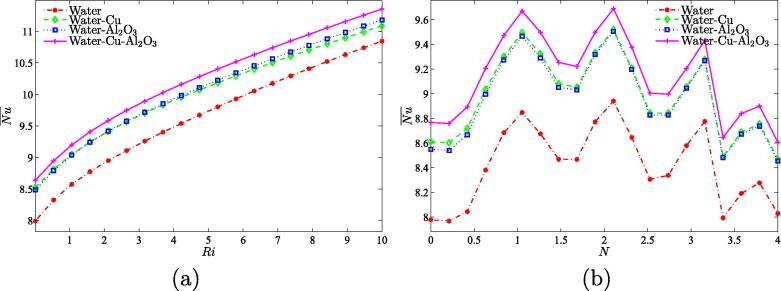

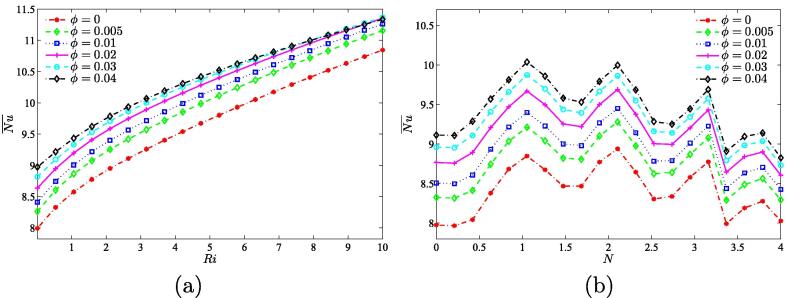

Fig. 8 portrays differences of with respect to the Ri and N for various types of nanofluids with 2% volume fraction at and . At a given value of Ri and N, it is seen that employing hybrid nanofluids offers a very good heat transfer behaviour in the cavity compared to the Cu-based nanofluid, Al2O3-based nanofluid, and certainly with the pure fluid. This is because the hybrid nanofluid holds the most important active thermal conductivity associated with other fluids. One notes that the rate of heat is a monotonously increasing function of Ri due to the predominance of the buoyancy effects, which increases the convective flow. Fig. 8(b) shows that, first, the presence of a specific number of undulations on the existing wall improves the rate of heat transfer. The reason is related to the enlargement in the heat exchange surface. Generally, beyond the undulations number , the mean Nusselt number declines by the rise in N parameter. Besides, we note optimum values of N toward the highest rate of heat transfer. The increase of Copper and Alumina hybrid nanoparticles in the receiving fluid improves heat transmission influenced by the enhancement of the overall heat conductivity from the hybrid nanofluids (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Average Nusselt number with (a) Ri and (b) N for various types of nanoparticles at and .

Fig. 9.

Average Nusselt number with (a) Ri and (b) N for different values of at hybrid nanofluid, and .

Conclusions

In this current numerical study, the Galerkin weighted residual finite element method is implemented toward determining the dimensionless conservation equations of mixed convective heat transfer problem numerically into the wavy-walled lid-driven hollow containing a square conductive solid. The cavity is loaded with a water-based hybrid nanofluid containing Cu-Al2O3 nanoparticles taking into account the two-phase nanofluid approach. Influences of various dimensionless parameters and their mutual effects have been investigated e.g., the Richardson number, composite nanoparticles volume fraction, undulations number, and dimensionless length and the position regarding the solid block. The amounts of the remaining parameters are kept unchanged. The conducted analysis indicates that employing hybrid nanofluids leads to higher heat transmission rates in comparison with other similar usual nanofluids based on Cu or Al2O3. The heat transmission rate is found to increase with the Richardson number and the volume fraction of hybrid nanoparticles. Besides, a high Richardson number reects a uniform distribution of the nanoparticles within the enclosure. The insertion of a solid block into the cavity conduces to alter the flow, heat transport, and the nanoparticles’ distribution behavior. In fact, the intensities of the mixed convective flow and the average heat transfer become decreasing functions of the solid block size, which enhances the thermophoresis effects, and as a result, a non-uniform distribution of nanoparticles is obtained. Also, it has been found that inserting the conducting block near the core of the cavity provides the best overall heat transfer rate. The migration of nanocomposites particles due to the Brownian and thermophoresis forces is modeled in the hybrid nanofluid. It is observed that the concentration of the hybrid nanofluid reduces about a typical value of 3.5% next to the hot wall. The observation is due to the thermophoresis force, which sweeps the particles against the temperature gradient from hot to cold. In contrast, the concentration of nanoparticles is increased by about 1.5% next to the cold wall. Further, results reveal that imposing certain specific undulations on the vertical active walls can be a beneficial controlling element for the enhancement of heat transfer and nanoparticle distributions inside the enclosure.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the financial support received from the Malaysian Ministry of Education research grant FRGS/1/2019/STG06/UKM/01/2.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Ghalambaz, Email: mohammad.ghalambaz@tdtu.edu.vn.

Ishak Hashim, Email: ishak_h@ukm.edu.my.

Ali J. Chamkha, Email: alichamkha@duytan.edu.vn.

References

- 1.Khanafer K., Aithal S.M. Mixed convection heat transfer in a lid-driven cavity with a rotating circular cylinder. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2017;86:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Amiri A., Khanafer K. Fluid–structure interaction analysis of mixed convection heat transfer in a lid-driven cavity with a flexible bottom wall. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2011;54(17–18):3826–3836. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanafer K.M., Al-Amiri A.M., Pop I. Numerical simulation of unsteady mixed convection in a driven cavity using an externally excited sliding lid. Eur J Mech-B/Fluids. 2007;26(5):669–687. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanafer K.M., Chamkha A.J. Mixed convection flow in a lid-driven enclosure filled with a fluid-saturated porous medium. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1999;42(13):2465–2481. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muhammad R., Khan M.I., Jameel M., Khan N.B. Fully developed darcy-forchheimer mixed convective flow over a curved surface with activation energy and entropy generation. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;188:105298. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivasankaran S., Mansour M.A., Rashad A.M., Bhuvaneswari M. MHD mixed convection of Cu–water nanofluid in a two-sided lid-driven porous cavity with a partial slip. Numer Heat Transf, Part A: Appl. 2016;70(12):1356–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rashad A.M., Sivasankaran S., Mansour M.A., Bhuvaneswari M. Magneto-convection of nanofluids in a lid-driven trapezoidal cavity with internal heat generation and discrete heating. Numer Heat Transf, Part A: Appl. 2017;71(12):1223–1234. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan M.I., Alzahrani F., Hobiny A. Heat transport and nonlinear mixed convective nanomaterial slip flow of Walter-B fluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms. Alexandria Eng J. 2020;59(3):1761–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oztop H.F., Al-Salem K., Pop I. MHD mixed convection in a lid-driven cavity with corner heater. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2011;54(15–16):3494–3504. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheikholeslami M., Chamkha A.J. Flow and convective heat transfer of a ferro-nanofluid in a double-sided lid-driven cavity with a wavy wall in the presence of a variable magnetic field. Numer Heat Transf, Part A: Appl. 2016;69(10):1186–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizul F.M., Alsabery A.I., Hashim I. Heatlines visualisation of mixed convection flow in a wavy heated cavity filled with nanofluids and having an inner solid block. Int J Mech Sci. 2020;175:105529. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karbasifar B., Akbari M., Toghraie D. Mixed convection of water-aluminum oxide nanofluid in an inclined lid-driven cavity containing a hot elliptical centric cylinder. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;116:1237–1249. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangawane K.M. Computational analysis of mixed convection heat transfer characteristics in lid-driven cavity containing triangular block with constant heat flux: Effect of prandtl and grashof numbers. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;105:34–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohebbi R., Rashidi M.M. Numerical simulation of natural convection heat transfer of a nanofluid in an L-shaped enclosure with a heating obstacle. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2017;72:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angeli D., Levoni P., Barozzi G.S. Numerical predictions for stable buoyant regimes within a square cavity containing a heated horizontal cylinder. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2008;51(3–4):553–565. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma Y., Mohebbi R., Rashidi M.M., Yang Z. Simulation of nanofluid natural convection in a U-shaped cavity equipped by a heating obstacle: Effect of cavity’s aspect ratio. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2018;93:263–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam A.W., Sharif M.A.R., Carlson E.S. Mixed convection in a lid driven square cavity with an isothermally heated square blockage inside. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2012;55(19–20):5244–5255. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oztop H.F., Dagtekin I. Mixed convection in two-sided lid-driven differentially heated square cavity. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2004;47(8–9):1761–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Z.T., Fan L.W., Hu Y.C., Cen K.F. Prandtl number dependence of laminar natural convection heat transfer in a horizontal cylindrical enclosure with an inner coaxial triangular cylinder. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2010;53(7–8):1333–1340. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J.R., Park I.S. Numerical analysis for prandtl number dependency on natural convection in an enclosure having a vertical thermal gradient with a square insulator inside. Nucl Eng Technol. 2012;44(3):283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kousar N, Rehman KU, Al-Kouz W, Al-Mdallal QM, Malik MY. Hybrid mesh finite element analysis (HMFEA) of uniformly heated cylinder in a partially heated moon shaped enclosure. Case Stud Therm Eng 2020;100713.

- 22.Rehman K.U., Al-Mdallal Q.M., Tlili I., Malik M.Y. Impact of heated triangular ribs on hydrodynamic forces in a rectangular domain with heated elliptic cylinder: Finite element analysis. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2020;112:104501. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheikholeslami M., Ashorynejad H., Rana P. Lattice boltzmann simulation of nanofluid heat transfer enhancement and entropy generation. J Mol Liq. 2016;214:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahdavi M., Sharifpur M., Meyer J.P. Implementation of diffusion and electrostatic forces to produce a new slip velocity in the multiphase approach to nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2017;307:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan M.I., Waqas M., Hayat T., Alsaedi A. A comparative study of casson fluid with homogeneous-heterogeneous reactions. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;498:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hashim I., Alsabery A.I., Sheremet M.A., Chamkha A.J. Numerical investigation of natural convection of Al2O3-water nanofluid in a wavy cavity with conductive inner block using buongiorno’s two-phase model. Adv Powder Technol. 2019;30(2):399–414. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsabery A.I., Sheremet M.A., Chamkha A.J., Hashim I. MHD convective heat transfer in a discretely heated square cavity with conductive inner block using two-phase nanofluid model. Scient Rep. 2018;8(1):1–23. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25749-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izadi M., Sinaei S., Mehryan S., Oztop H.F., Abu-Hamdeh N. Natural convection of a nanofluid between two eccentric cylinders saturated by porous material: Buongiorno’s two phase model. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2018;127:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toosi M.H., Siavashi M. Two-phase mixture numerical simulation of natural convection of nanofluid flow in a cavity partially filled with porous media to enhance heat transfer. J Mol Liq. 2017;238:553–569. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Izadi M., Hoghoughi G., Mohebbi R., Sheremet M. Nanoparticle migration and natural convection heat transfer of Cu-water nanofluid inside a porous undulant-wall enclosure using LTNE and two-phase model. J Mol Liq. 2018;261:357–372. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J., Khan M.I., Khan W.A., Abbas S.Z., Khan M.I. Transportation of heat generation/absorption and radiative heat flux in homogeneous–heterogeneous catalytic reactions of non-newtonian fluid (oldroyd-b model) Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;189:105310. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alsabery A.I., Ismael M.A., Chamkha A.J., Hashim I. Mixed convection of Al2O3-water nanofluid in a double lid-driven square cavity with a solid inner insert using buongiorno’s two-phase model. Int J.Heat Mass Transf. 2018;119:939–961. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bozorg M.V., Siavashi M. Two-phase mixed convection heat transfer and entropy generation analysis of a non-newtonian nanofluid inside a cavity with internal rotating heater and cooler. Int J Mech Sci. 2019;151:842–857. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barnoon P., Toghraie D., Dehkordi R.B., Abed H. MHD mixed convection and entropy generation in a lid-driven cavity with rotating cylinders filled by a nanofluid using two phase mixture model. J Magn Magn Mater. 2019;483:224–248. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siavashi M., Karimi K., Xiong Q., Doranehgard M.H. Numerical analysis of mixed convection of two-phase non-newtonian nanofluid flow inside a partially porous square enclosure with a rotating cylinder. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;137(1):267–287. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen D., Ding Y. Experimental investigation into convective heat transfer of nanofluids at the entrance region under laminar flow conditions. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2004;47(24):5181–5188. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buongiorno J. Convective transport in nanofluids. J Heat Transf. 2006;128(3):240–250. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darzi A.A.R., Farhadi M., Lavasani A.M. Two phase mixture model of nano-enhanced mixed convection heat transfer in finned enclosure. Chem Eng Res Des. 2016;111:294–304. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motlagh S.Y., Soltanipour H. Natural convection of al2o3-water nanofluid in an inclined cavity using buongiorno’s two-phase model. Int J Therm Sci. 2017;111:310–320. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esfandiary M., Mehmandoust B., Karimipour A., Pakravan H.A. Natural convection of al 2 o 3–water nanofluid in an inclined enclosure with the effects of slip velocity mechanisms: Brownian motion and thermophoresis phenomenon. Int J Therm Sci. 2016;105:137–158. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tayebi T., Chamkha A.J. Free convection enhancement in an annulus between horizontal confocal elliptical cylinders using hybrid nanofluids. Numer Heat Transf, Part A: Appl. 2016;70(10):1141–1156. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tayebi T., Chamkha A.J. Buoyancy-driven heat transfer enhancement in a sinusoidally heated enclosure utilizing hybrid nanofluid. Computational Thermal Sciences: An. Int J. 2017;9(5) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahdavi M., Sharifpur M., Ghodsinezhad H., Meyer J.P. A new combination of nanoparticles mass diffusion flux and slip mechanism approaches with electrostatic forces in a natural convective cavity flow. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;106:980–988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ghalambaz M., Sheremet M.A., Mehryan S.A.M., Kashkooli F.M., Pop I. Local thermal non-equilibrium analysis of conjugate free convection within a porous enclosure occupied with Ag–MgO hybrid nanofluid. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;135(2):1381–1398. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghalambaz M., Mehryan S.A.M., Izadpanahi E., Chamkha A.J., Wen D. MHD natural convection of Cu–Al2O3 water hybrid nanofluids in a cavity equally divided into two parts by a vertical flexible partition membrane. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;138(2):1723–1743. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahdavi M., Sharifpur M., Ghodsinezhad H., Meyer J.P. Experimental and numerical study of the thermal and hydrodynamic characteristics of laminar natural convective flow inside a rectangular cavity with water, ethylene glycol–water and air. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2016;78:50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chamkha A.J., Miroshnichenko I.V., Sheremet M.A. Numerical analysis of unsteady conjugate natural convection of hybrid water-based nanofluid in a semicircular cavity. J Therm Sci Eng Appl. 2017;9(4) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mansour M.A., Siddiqa S., Gorla R.S.R., Rashad A.M. Effects of heat source and sink on entropy generation and MHD natural convection of Al2O_3-Cu/water hybrid nanofluid filled with square porous cavity. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2018;6:57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mohebbi R., Izadi M., Delouei A.A., Sajjadi H. Effect of MWCNT–Fe3O4/water hybrid nanofluid on the thermal performance of ribbed channel with apart sections of heating and cooling. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;135(6):3029–3042. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nadeem S., Abbas N., Malik M.Y. Inspection of hybrid based nanofluid flow over a curved surface. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;189:105193. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abbas N, Malik MY, Alqarni MS, Nadeem S. Study of three dimensional stagnation point flow of hybrid nanofluid over an isotropic slip surface. Phys A: Stat Mech Its Appl 2020;124020.

- 52.Suresh S., Venkitaraj K.P., Selvakumar P., Chandrasekar M. Effect of Al2O3–Cu/water hybrid nanofluid in heat transfer. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2012;38:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tayebi T., Chamkha A.J. Entropy generation analysis due to MHD natural convection flow in a cavity occupied with hybrid nanofluid and equipped with a conducting hollow cylinder. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2020;139(3):2165–2179. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehryan S.A.M., Izadpanahi E., Ghalambaz M., Chamkha A. Mixed convection flow caused by an oscillating cylinder in a square cavity filled with Cu–Al2O3/water hybrid nanofluid. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019;137(3):965–982. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ismael M.A., Armaghani T., Chamkha A.J. Mixed convection and entropy generation in a lid-driven cavity filled with a hybrid nanofluid and heated by a triangular solid. Heat Transf Res. 2018;49(17) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chamkha A.J., Doostanidezfuli A., Izadpanahi E., Ghalambaz M. Phase-change heat transfer of single/hybrid nanoparticles-enhanced phase-change materials over a heated horizontal cylinder confined in a square cavity. Adv Powder Technol. 2017;28(2):385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghalambaz M., Doostani A., Chamkha A.J., Ismael M.A. Melting of nanoparticles-enhanced phase-change materials in an enclosure: Effect of hybrid nanoparticles. Int J Mech Sci. 2017;134:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghalambaz M., Doostani A., Izadpanahi E., Chamkha A.J. Phase-change heat transfer in a cavity heated from below: The effect of utilizing single or hybrid nanoparticles as additives. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2017;72:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Izadi M., Mohebbi R., Delouei A.A., Sajjadi H. Natural convection of a magnetizable hybrid nanofluid inside a porous enclosure subjected to two variable magnetic fields. Int J Mech Sci. 2019;151:154–169. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goudarzi S., Shekaramiz M., Omidvar A., Golab E., Karimipour A., Karimipour A. Nanoparticles migration due to thermophoresis and brownian motion and its impact on Ag-MgO/Water hybrid nanofluid natural convection. Powder Technol. 2020;375:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sundar L.S., Sharma K.V., Singh M.K., Sousa A.C.M. Hybrid nanofluids preparation, thermal properties, heat transfer and friction factor–a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;68:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gupta M., Singh V., Kumar S., Kumar S., Dilbaghi N., Said Z. Up to date review on the synthesis and thermophysical properties of hybrid nanofluids. J Clean Prod. 2018;190:169–192. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alsabery A.I., Ghalambaz M., Armaghani T., Chamkha A., Hashim I., Saffari Pour M. Role of rotating cylinder toward mixed convection inside a wavy heated cavity via two-phase nanofluid concept. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(6):1138. doi: 10.3390/nano10061138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corcione M. Empirical correlating equations for predicting the effective thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity of nanofluids. Energy Convers Manage. 2011;52(1):789–793. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alsabery A.I., Hashim I., Hajjar A., Ghalambaz M., Nadeem S., Saffari Pour M. Entropy generation and natural convection flow of hybrid nanofluids in a partially divided wavy cavity including solid blocks. Energies. 2020;13(11):2942. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Paroncini M., Corvaro F., Montucchiari A., Nardini G. A numerical and experimental analysis on natural convective heat transfer in a square enclosure with partially active side walls. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2012;36:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Putra N., Roetzel W., Das S.K. Natural convection of nano-fluids. Heat Mass Transf. 2003;39(8–9):775–784. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corcione M., Cianfrini M., Quintino A. Two-phase mixture modeling of natural convection of nanofluids with temperature-dependent properties. Int J Therm Sci. 2013;71:182–195. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chon C.H., Kihm K.D., Lee S.P., Choi S.U. Empirical correlation finding the role of temperature and particle size for nanofluid (al2o3) thermal conductivity enhancement. Appl Phys Lett. 2005;87(15):3107. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cianfrini C., Corcione M., Habib E., Quintino A. Buoyancy-induced convection in Al2O3/water nanofluids from an enclosed heater. Eur J Mech-B/Fluids. 2014;48:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ho C., Liu W., Chang Y., Lin C. Natural convection heat transfer of alumina-water nanofluid in vertical square enclosures: An experimental study. Int J Therm Sci. 2010;49(8):1345–1353. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bergman T.L., Incropera F.P. 6th ed. Wiley; New York: 2011. Introduction to heat transfer. [Google Scholar]