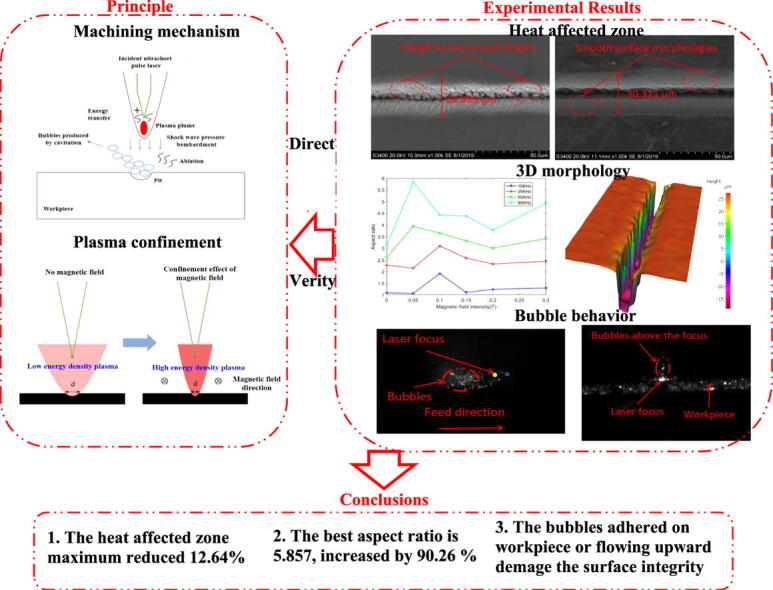

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Laser induced plasma micro-machining (LIPMM), Surface integrity, Geometrical shape, Bubble behavior, Magnetic field assisted technique, Single-crystal silicon

Abstract

Introduction

Laser induced plasma micro-machining (LIPMM) has proved its superiority in micro-machining of hard and brittle materials due to less thermal defects, smaller heat affected zone and larger aspect ratio compared to conventional laser ablation.

Objectives

In order to improve characteristics and stability of induced plasma, this paper proposed magnetically controlled LIPMM (MC-LIPMM) to achieve a good performance of processing single-crystal silicon which is widely used in solid state electronics and infrared optical applications.

Methods

A comprehensive study on surface integrity and geometrical shape was conducted based on the experimental method. Firstly, the mechanism of MC-LIPMM including laser-plasma, laser-materials interactions and transport effects was theoretically analyzed. Then a series of experiments was conducted to completely investigate the effect of magnetic field intensity, pulse repetition frequency, and bubble behavior on surface integrity and geometrical shape of micro channels.

Results

It revealed that magnetic field contributed to maximum reduction of 12.64% for heat affected zone and 62.57% for width while maximum increase of 26.23% for depth and 90.26% for aspect ratio.

Conclusion

This research confirms that MC-LIPMM can improve the machining characteristics of silicon materials and cavitation bubbles shows an apparently negative impact on the surface morphology.

Introduction

Single-crystal silicon is the key essential material of semiconductor, photoelectrical sensor, and infrared optics with excellent electrical and mechanical properties, and has been widely used in solid state electronics, MEMS, photovoltaic power, and infrared optical technologies for aerospace, automobile, telecommunication, biomedical applications [1]. However, single-crystal silicon shows strongly hard and brittle characteristics with a high degree of hardness (12 –14 GPa) but a low level of fracture toughness (~1 MPa·m1/2), which lead to low machining efficiency, high cost, poor machining performance, and high breakage rates during the micro scale material removal process [2]. Particularly, Goel et al. [3] and Chen et al. [4] pointed out that conventional mechanical machining technologies like turning, milling or grinding are restricted to hardness and brittleness of single-crystal silicon. These conventional macro/micro-machining processes exist considerable cutting force leading to severe tool wear and surface damage (micro-cracks), as well as low machining accuracy and efficiency, which requires new machining technologies to solve these drawbacks and achieve high machining quality of single-crystal silicon.

On the contrary, non-conventional physical machining technologies, like electrical discharge machining (EDM) [5] and laser machining [6], could provide great potential and superiority to no-contact machining of the difficult to melt materials with complex curved surfaces and 3D shapes via melting and vaporization. Pallav et al. [7] conducted a comparative study on laser micromachining and micro-EDM. It can be found that laser micromachining was probably a better choice for high-precision process of single-crystal silicon due to its no limitation of material conductivity and high machining efficiency. However, as Cheng et al. [8] found, thermal damage and stress variations induced by laser ablation process results in bad surface integrity with crystalline-amorphous transformations, intensive thermal-crack propagation, thick recast layer, and large heat affected zone. Thus, it is very important to improve laser ablation process and avoid excessive thermal concentration on the machined surface to reduce thermal stress and damages. Tangwarodomnukun, et al. [9] put laser micromachining of silicon in ice layer to control the excessive heat conducting toward the silicon substrate and also to impede the removed debris depositing on the machined surface. But compared with ultrashort-pulse lasers, they adopted nanosecond pulsed lasers to conduct micro machining process, which still produced large amount of heat to result in thick recast layer. Since thermal damage induced by long-pulse lasers restricts the maximum machining accuracy and affects surface quality, ultrashort-pulse lasers, like picosecond/femtosecond-pulse lasers, could relieve this thermal damage to some extent and fabricate high-precision structures in micro/nano scales. Soltani et al. [10] and Fang et al. [11] presented the machining surface integrity of picosecond pulsed laser micromachining of silicon nitride and silicon wafer including surface topography, microstructure, width of thermal damages, heat-affected zone (HAZ) and residual stress of machined surface. But ultrashort-pulse laser can’t completely eliminate thermal defects, micro-cracks, recast layer and heat affect area, which severely influenced surface integrity and its performance of fabricating micro/nano-structures.

In order to increase the material removal rate (MRR) and further reduce thermal damage in the ultrashort-pulse laser micro machining, Pallav and Ehmann [12] first proposed laser induced plasma micro machining(LIPMM) technique using induced plasma instead of laser pulse to physically interact with materials, which shows enormous potential for multi-materials processing, complex features and high precision micro-structure processing. The plasma induced by ultrashort-pulse laser located at the focal spot of laser beam inside a transparent dielectric medium. The material removal mechanism of LIPMM is the combined results of thermal vaporization by plasma-material interaction due to thermal energy in the plasma, and mechanical erosion by shock waves and cavitation due to mechanical energy in the plasma. Thus geometrical shape and intensity of plasma plume could significantly affect machining efficiency, the geometric characteristics of micro-structures, and their surface integrity, and these characteristics of plasma plume should be enhanced in some way.

Some researches revealed that magnetic field assisted technology could confine the induced plasma and regulate its geometric features via controlling the motion of charge particles in the plasma [13], [14]. Pisarczyk et al [15] implemented external magnetic field to generate an elongated plasma column with higher electron density, and VanZeeland et al. [16] experimentally studied the expansion of an ambient magnetized plasma induced by a dense laser. Begimkulov et al. [17] conducted numerical and experimental analysis on the evolution of laser induced plasma in the transverse magnetic field and revealed that the radial dimension of the plasma can be enhanced. Farrokhi et al. [18], [19] also pointed out that a constant axial magnetic field could enhance quality and speed of nanosecond-pulse laser ablation of silicon due to the confinement of laser-induced plasma by the magnetic field and specific propagation effects in the magnetized plasma. Therefore, from above researchers’ work, external magnetic field assisted method can effectively regulate the geometric shape, size and fluence of induced plasma by pulsed laser, which could contribute to improve machining performance including surface integrity and machining efficiency of LIPMM process through regulating induced plasma.

Recently, some researchers have begun to explore the effect of magnetic fields on machining characteristics in LIPMM. Saxena et al. [20] applied an external unidirectional magnetic field to LIPMM, which increased plasma energy by 70% and depth of micro-structure by 50% in a magnetic field of 5400 Gauss. Tang et al. [21] implemented repulsive magnetic field–assisted laser-induced plasma micromachining of single crystal silicon to achieve a high-quality smooth and narrow microgroove without thermal defects. Although surface quality and geometrical shape of machined single crystal silicon are critical to characteristics of micro-structure, few researches focused on comprehensively studying the surface integrity of magnetically controlled laser-induced plasma micro-machining (MC-LIPMM). Particularly, the synesthetic effects of bubble behavior generated by mechanical energy of plasma and erosion generated by thermal energy of plasma on the surface integrity should be taken into considerations.

Based on above research problems, this article comprehensively investigates machining characteristics of magnetic field assisted laser induced plasma micro-machining single-crystal silicon. Section 2 presents the principle of plasma behavior in the presence of magnetic fields and improvement mechanism of MC-LIPMM of single-crystal silicon. The experimental procedures including setup, design and measurement method are described in Section 3. Experimental results and discussions about the effects of magnetic field and pulse repetition frequency on surface integrity and microgroove shape are conducted in Section 4. Conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

Background

Laser induced plasma generation

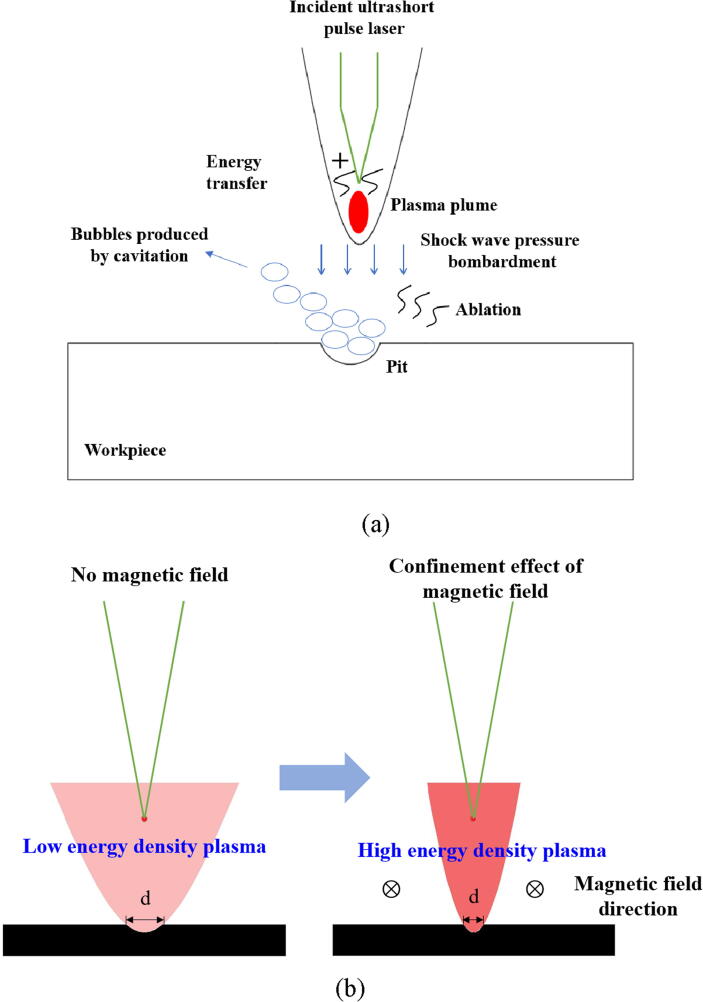

The generation of plasma is due to the optical breakdown mechanisms when the laser peak power density exceeds a threshold value in a dielectric as shown in Fig. 1(a), thus the plasma is the basement and key to explore the machining mechanism of MF-LIPMM.

Fig. 1.

The principle of LIPMM and effect of magnetic field on plasma: (a) the principle diagram of LIPMM; (b) the effect of magnetic field on plasma confinement [21].

The evolution equation of free electrons in a dielectric can be calculated by [22]:

| (1) |

where (dρ/dt)mp denotes multiphoton ionization, ηcascρ denotes cascade ionization, and ηrecρ2 denotes recombination. It can be found from Eq. (1) that the intensity and shape of plasma is determined by the free electrons.

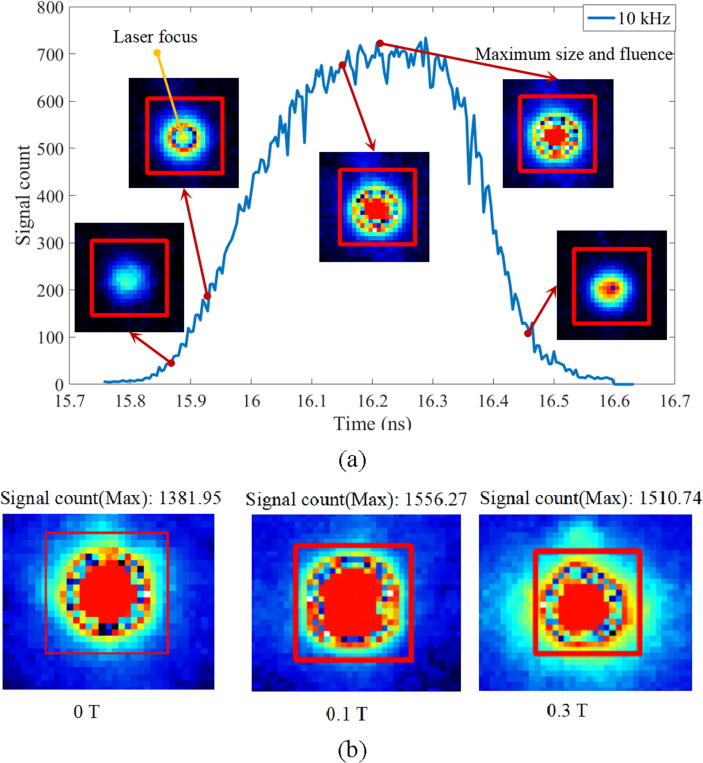

To show the generation process of laser induced plasma intuitively, a Nd-YVO4 laser (Lumera Lasers Inc.) and an ultra-fast gated camera (Model: LaVision PicoStar HR 12) were applied to produce and record the diffusion of plasma by experimental method as displayed in Fig. 2(a). The repetition frequency of pulse laser is 10 kHz, and the resolution of camera is 1 K. From Fig. 2(a), it can be obtained that the plasma induced by laser was centered on the laser focus and the plasma continued to expand when the pulse laser existed, and dissipated as the laser disappeared. The plasma began to appear when the scanning phase delay time was 15.756 ns, and with the increase of time, the size and fluence (signal count) of plasma increased firstly until reaching a maximum at 16.208 ns. After that, the plasma starts to dissipate until 16.596 ns, and the whole plasma duration is 0.84 ns.

Fig. 2.

The plasma images under different times and magnetic field strengths: (a) the plasma images and its fluence under different time; (b) the plasma images and its largest fluence under different magnetic field strengths.

The mechanism of laser induced plasma micro-machining silicon

The mechanism of magnetic field assisted LIP micro machining single crystal silicon mainly depends on laser-plasma interactions, laser-material surface coupling, and transport & thermomagnetic effects as shown in Fig. 1(a).

Laser-plasma interaction effects under magnetic field

Plasma magnetization can significantly improve the performance of laser-material surface coupling in some respects, including the fastest rate of LIP confinement, modification of the LIP optical response, and characteristics of LIP expansion under the effect of external magnetic field [18], [19], [21], as shown in Fig. 1(b).

On the side of the fastest rate of LIP confinement, the speed rate of LIP confinement by magnetic field is confirmed via calculating cyclotron frequency and cyclotron period as the following equations [18].

| (2) |

where m is mass of a charged plasma particle; q is the particle charge; and B is magnetic field intensity. As for the heavy mass part in LIP, the shortest cyclotron period of 12.06 μs is attributed to a single-charged ion of Si (m = 28.085 atomic units of mass [23]; ωC = 0.521 × 106 rad/s at B = 0.1 T). Considering a pulse duration of 10 ps, the charged plasma particle obtains a completely negligible angular travel motion of 0.521 × 10-6 rad. This means that the confinement effects of heavy-mass magnetic field assisted LIP part can be completely neglected during direct picosecond pulsed laser action and early stages of machining, but major confinement effects would gradually happen at the stages of LIP machining, cooling and deposition.

In terms of the Appleton formula for the dielectric response of a magnetized plasma, Farrokhi [18] found that modification of the LIP optical response could be nearly neglected because the cyclotron frequencies of heavy-mass LIP components and electrons are all far less than the pulsed laser frequency (its order about 104). This means that line pulse laser propagates through the induced plasma with little influence under the external magnetic field.

LIP expansion by magnetic field is characterized based on the Larmor radius of the LIP particles as following equation [18].

| (3) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant; v is average particle speed. When TBOIL = 3558 K, the average speed of plasma particles is 1.77 × 103 m/s, and the Larmor radius is 2.69 mm for a single charged silicon ion [23]. Since compared with the average speed of plasma particles the speed of the induced plasma front can amount to 105 m/s, which is faster by two orders of magnitude, plasma particles could expand further from the crater during the plasma cooling and debris recasting. Additionally, the thermal radiation of LIP can make the machining crater depth increased by 10%-20%.

Laser-materials interaction and transport effects under magnetic field

The plasma intensity can be further enhanced by the change of material optical properties of silicon under magnetic field, which includes the promotion and the absorption of light energy by free electrons [24]. This laser-materials interaction can also change the transport effects in terms of reflectivity. Magneto-absorption for inter-band transitions is another phenomenon when machining silicon in MF-LIPMM, which can contribute to the resonant inter-band transitions and then increases the absorption of light in the presence of magnetic field.

To verify above theoretical analysis, the comparison of plasma in the presence of magnetic field or not was performed. As shown in Fig. 2 (b), the plasma pictures were captured when their fluence were the largest and stable. It can be seen that compared to the plasma in the absence of magnetic field, the size and fluence of plasma in the presence of magnetic field were larger, and the greatest enhancement effect of magnetic field on plasma is under a magnetic field of 0.1 T. The largest growth of plasma fluence was 12.61% when the magnetic field strength was 0.1 T, compared to that of 0 T.

In a word, the assisted magnetic field could contribute to significantly increase the depth and aspect ratio of machining area and improve the machining performance of LIPMM during LIP micro machining single crystal silicon.

Experimental procedure

Experimental setup

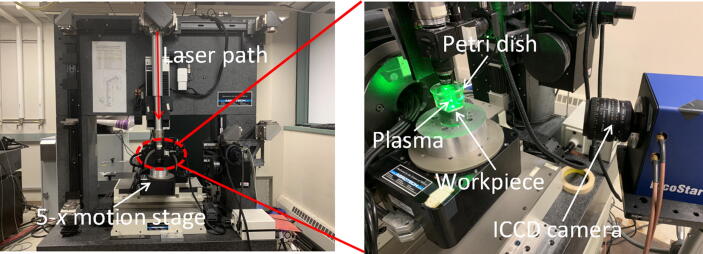

An Nd-YVO4 laser (Lumera Lasers Inc.) was used in this study, with a 532 nm wavelength and 8 ps pulse duration operating at its second harmonic. The experimental setup for LIPMM was shown in Fig. 3. The workpiece was placed in a petri dish, and immersed into a 10 mm of distilled water. The petri dish was taped on a 5-x freedom motion stage with a resolution of 10 nm. Neodymium permanent magnets (Grade N52) with a surface field of 5,400 Gauss were applied to produce magnetic field. Single-crystal silicon was selected as workpiece material due to its wide application in aerospace field.

Fig. 3.

The experimental setup.

Experimental design and measurement

The different process parameters including pulse repetition frequency (10 kHz, 25 kHz, 50 kHz and 80 kHz) and magnetic field intensities (0.05 T, 0.1 T, 0.15 T, 0.2 T and 0.3 T) were selected to conduct experiments.

The plasma fluence in the magnetic field was also observed by an ultra-fast gated camera (Model: LaVision PicoStar HR 12). The machined channels were cleaned for 5 min to eliminate the deposition by using Ultrasonic cleaning machine. The morphology of the machined channels were examined by SEM (Model: EPIC SEM Hitachi S-3400). The size of microgrooves including its width and depth were detected by an Alicona infinite focus measurement 3D metrology system. Besides, the bubble motion was observed and recorded by using high speed camera with 2000 fps in MF-LIPMM.

Results and discussion

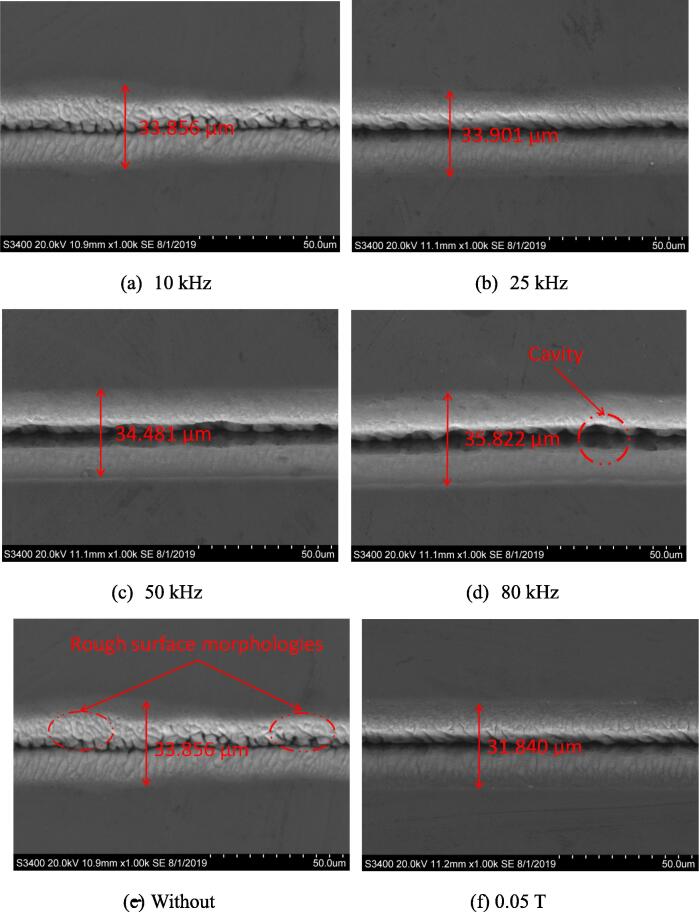

Effect of repetition frequency on the surface integrity

The effect of repetition frequency on the surface integrity of machined channels is investigated in LIPMM under different repetition frequency as shown in Fig. 4(a)-(d). The surface morphologies, and width of grooves including the heat affected zone and channel are both analyzed. From Fig. 4(a)-(d), it can be obtained that larger repetition frequency will obtain larger width of grooves and better surface morphologies including finer texture, more straight and homogeneous heat affected zone. This can be attributed to that larger repetition frequency means more numerous laser pulses and total laser power will be used to induce the plasma under same machining time, which can promote stronger multiphoton ionization and cascade ionization, resulting in more numerous excited free electrons and ions. This will contribute to larger size of and intensity of plasma, and then more sufficient thermal material removal and solidification process, finally lead to refined grain of surface texture and larger head affected zone [25]. However, too large repetition frequency maybe results in the cavity generated in the channels on account of bubbles problem, which is harmful for surface quality and will be further investigated in following section.

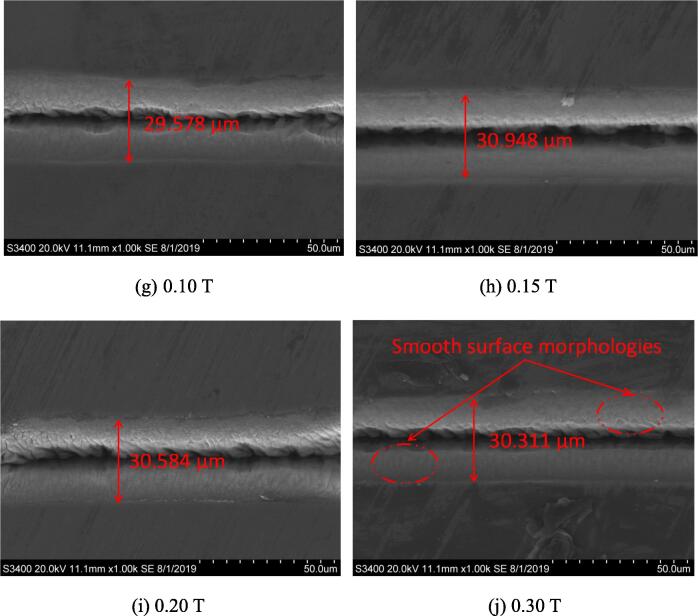

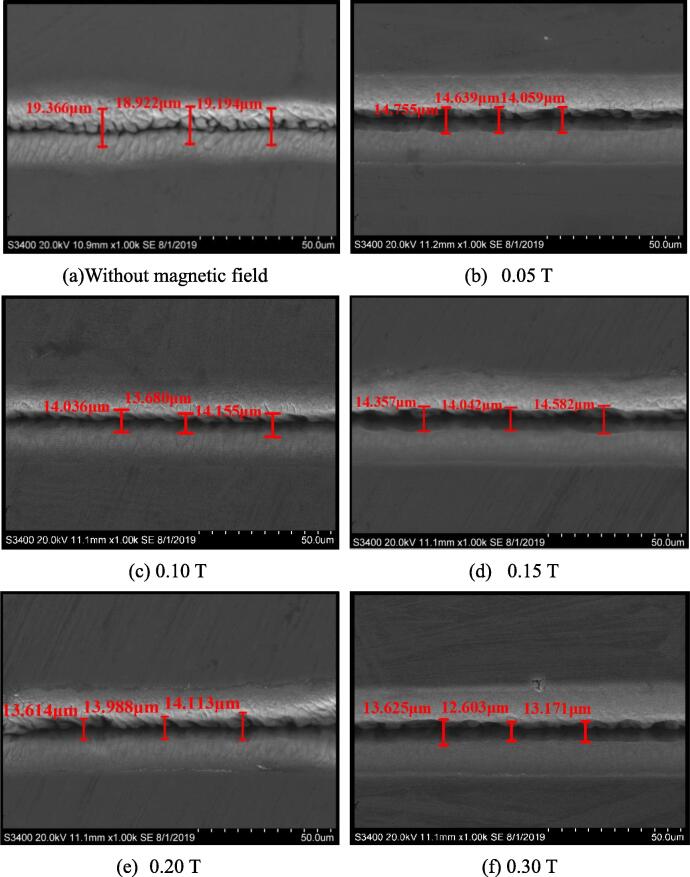

Fig. 4.

Surface morphologies of channel generated by MF-LIPMM under different repetition frequency (a-d) and different magnetic field strength by 10 kHz (e-j).

Effect of magnetic field on surface integrity

To explore the effects of magnetic field on surface integrity when machining silicon, the surface integrity of the machined channels including surface morphologies, heat affected zone, and element content analysis are all measured in MF-LIPMM. The surface morphologies and heat affected zone are shown in Fig. 4(e)-(j) under magnetic field strengths from 0 T to 0.3 T. From Fig. 4(e)-(j), it can be seen that the rough surface morphologies obtained without magnetic field are gradually transformed into smoother in the presence of magnetic field, especially when the magnetic field strength is larger than 0.1 T. The surface morphologies become more uniform along the channels as shown in Fig. 4(e), (f) and (h). The results of width of machined groove including heat affected zone and channel also indicate that magnetic field can decrease the heat affected zone with maximum reduction of 12.64% under 0.1 T magnetic field as shown in Fig. 4. These can be explained that on the one hand, magnetic field can confine the electrons of plasma within the central part of LIP due to large cyclotron frequency for plasma particles and small Larmor radius of electrons, which decreases the geometric dimension of plasma in this direction. On the other hand, magnetic field will also increase the plasma intensity when machining silicon materials by plasma-propagation effects including plasma magnetization and magneto-absorption effects. Moreover, thermal radiation of plasma will be beneficial to material removal [26]. The Above results will contribute to more extensive material removal in depth direction and less solidification in width direction.

Table 1 presents the comparison of machining performance by different laser machining methods from related literatures. Compared with other researches about laser machining silicon, the best recast layer and heat-affected zone were about 5 μm and 14.789 μm, which both have been reduced significantly in this study. As Tang et al. [21] stated, magnetic field and laser processing in liquid could contribute to achieve high-quality smooth surface without obvious thermal defects.

Table 1.

Comparison of machining performance by different laser machining methods.

| Machining technique | Types of laser | The depth of micro groove (μm) | The width of micro groove (μm) | The aspect ratio | Thickness of recast layer(μm) | Heat affected zone (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang et al. (2019) | Magnetic field–assisted LIPMM in ethanol | Femtosecond pulse laser with with a wavelength of 520 nm | – | 11 | – | Reduced | Reduced |

| Tangwarodomnukun et al. (2018) | Laser micromachining in air | Nanosecond pulse fberlaser with a wavelength of 1064 nm | – | 140 | – | 80 | Reduce |

| Tangwarodomnukun et al. (2018) | Laser micromachining in ice layer | Nanosecond pulse fberlaser with a wavelength of 1064 nm | 110 | 20 | 5.5 | 30 | Reduced |

| Farrokhi et al. (2016) | Magnetic field assisted laser ablation | UV nanosecond pulse laser with a wavelength of 355 nm | 9.76 | – | – | – | – |

| Saxena et al. (2014) | LIPMM in water | Picosecond pulse laser with a wavelength of 532 nm | 11 | 10 | 1.1 | – | no significant |

| Our study | MC-LIPMM in water | Picosecond pulse laser with a wavelength of 532 nm | 49.42 | 8.438 | 5.857 | About 5 | 14.789 |

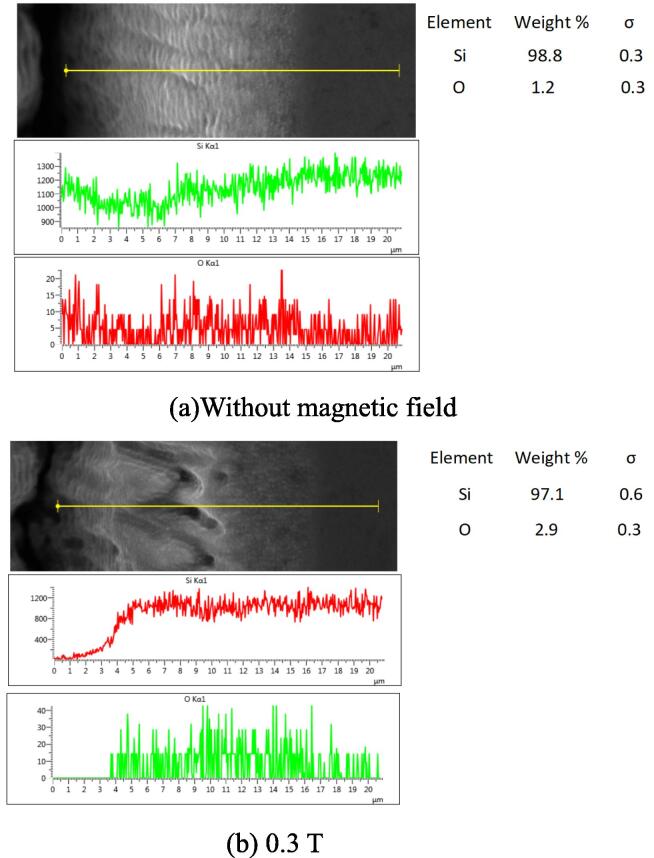

The element content analysis is also conducted to further explore the impact mechanism of magnetic field on surface integrity with or without magnetic field in LIPMM as shown in Fig. 5. It can be found that the percentage of oxygen element is larger (2.9%) when there exists a magnetic field, compared to without magnetic field (1.2%). Larger percentage of oxygen element means more heat energy is transferred into workpiece, and more material is eroded, oxidized, and re-solidified, which further confirmed that magnetic field can promote more violent machining process and larger material removal. This is due to the fact larger plasma intensity can be achieved by magnetic field due to enhancement of the laser energy absorption.

Fig.5.

The element content analysis of the machined channel surface (repetition frequency 10 kHz).

Effect of magnetic field on the geometrical shape of micro channel

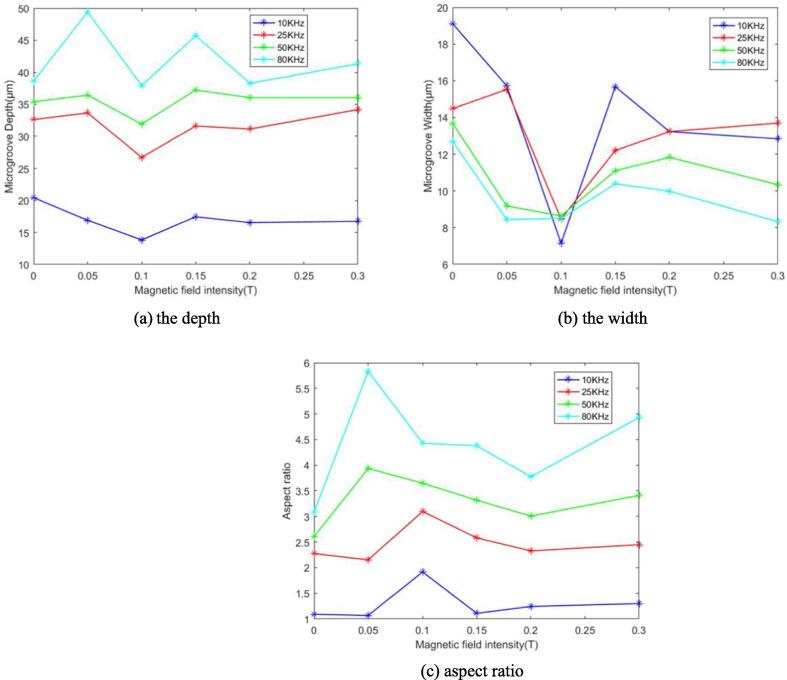

Extreme high aspect ratio is one of most important micro-machining performance indicators for the fabrication of micro or nano-structures. Thus the shape characteristics including depth, width, and aspect ratio (depth/width) of micro channels by MC-LIPMM, which are closely related to assisted magnetic field and laser parameters, are completely analyzed in this section. As the theoretical analysis in section 2, micro channels with large depth and high aspect ratio as well as fine surface integrity can be achieved via MC-LIPMM.

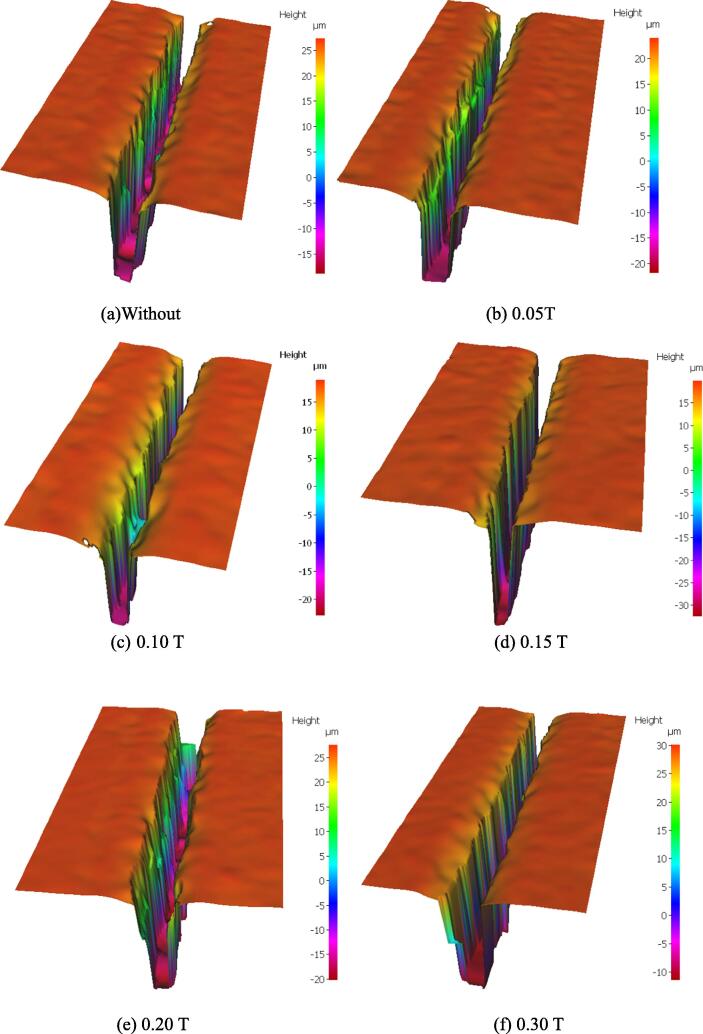

Fig. 6(a) and (b) present the variations of depth and width in micro channels by MC-LIPMM under the different magnetic field intensity (from 0 T to 0.3 T) and laser frequencies (from 10 to 80 kHz). It can be found that the assisted parallel magnetic field contributes to enlarge the depth of micro channels while narrow the width of micro channels, so aspect ratio can be significantly improved as shown in Fig. 6(c). As shown in SEM and 3D images about the shape of micro channels on single crystal silicon in MC-LIPMM, with the increase of magnetic field intensity, the widths of micro channels are sharply reduced while their depths are gradually enhanced under the laser frequency 10 kHz. By comprehensive analysis of Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, the average width and depth of micro channels are all much better than those of no magnetic field assisted LIPMM under different laser frequencies. Under the effect of magnetic field, the width can be maximum decreased by 62.57% with magnetic field intensity of 0.1 T and repetition frequency of 10 kHz, while the depth can be maximum increased by 26.23% with magnetic field intensity of 0.05 T and repetition frequency of 80 kHz.

Fig. 6.

The shape and aspect ratio of micro channels on single crystal silicon in MC-LIPMM.

Fig. 7.

SEM images of the width in micro channels under different magnetic field intensity (Repetition frequency 10 kHz).

Fig. 8.

3D images of the depth in micro channels under different magnetic field intensity (Repetition frequency 50 kHz).

Aspect ratio of micro channels apparently fluctuates with the increase of magnetic field intensity, but there is a critical point, the optimal value, during this variation process. The critical points of magnetic field strength affecting the depth, width and aspect ratio of micro channels all come out at about 0.1 T under low laser frequencies (like 10, 25 kHz), while their critical points appear earlier at about 0.05 T under high laser frequencies (like 50, 80 kHz). After the critical point, the shape characteristics of micro channels probably turn to be not outstanding even though they are still better than those of no magnetic field assisted LIPMM. The best aspect ratio of 5.857, increased by 90.26%, can be obtained with magnetic field intensity of 0.05 T and repetition frequency of 80 kHz.

Above phenomena can be attributed to that on the one hand, the optical properties of silicon are modified by a magnetic field, which contribute the absorption modification of free conduction electrons due to the generation of two minima on the reflectivity spectrum in silicon [27]. On the other hand, magnetic field can increase the electron density in the plasma by the suppression of the loss rate of free diffusion and confinement effects, which leads to larger collision frequencies between electrons-ions and more numerous excited electrons, resulting in larger laser absorption ratios and a further increase in intensity and temperature of plasma [28]. It’s worth to mention that with the increase of the temperature of the plasma, the collision frequency of electrons-ions will inversely decrease, which indicates that there is a limit in the enhancement effect of magnetic field on plasma. Furthermore, the confinement effects of the external magnetic field on free electrons in the plasma plume could reshape the profile of the induced plasma into slim plume, which is attributed to narrow width and enlarge depth of micro channels by MC-LIMPP.

As shown in Table 1, the best aspect ratio of the processed micro-grooves by MC-LIPMM was 5.857 μm with corresponding groove depth and width of 8.438 μm and 49.42 μm in our study. Compared with the aspect ratio of laser machining silicon without magnetic field assisted from Tangwarodomnukun et al. [9], the aspect ratio has been increased by 6.5%, and the line width can be narrowed by 57.81%. Thus magnetic field can effectively regulate the laser-induced plasma processing to achieve high aspect ratio.

Bubble behavior

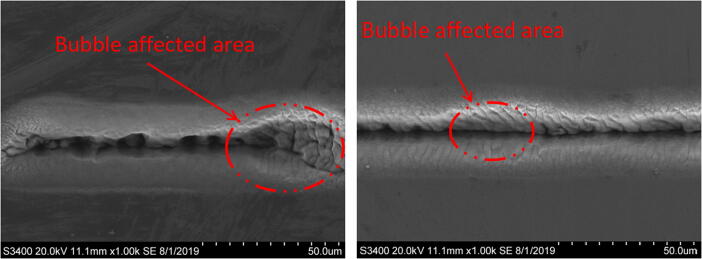

The expanding cavitation bubbles induced by the plasma plume on the laser-irradiated area has an important effect on machining surface integrity in LIPMM. Not only the generation and expansion of bubbles can produce a shock pressure and liquid jets in the surrounding water and workpiece [29], but also exerts negative effect on the stabilization of the plasma through the scattering and refraction of the laser beam [30]. The bubble behavior is more violent when machining single crystal silicon due to its high reflectivity and special optical properties. As shown in Fig. 9, the huge cavity induced by the bubbles explosion will absolutely damage the machined surface integrity and machining accuracy.

Fig. 9.

SEM images of bubble affected area.

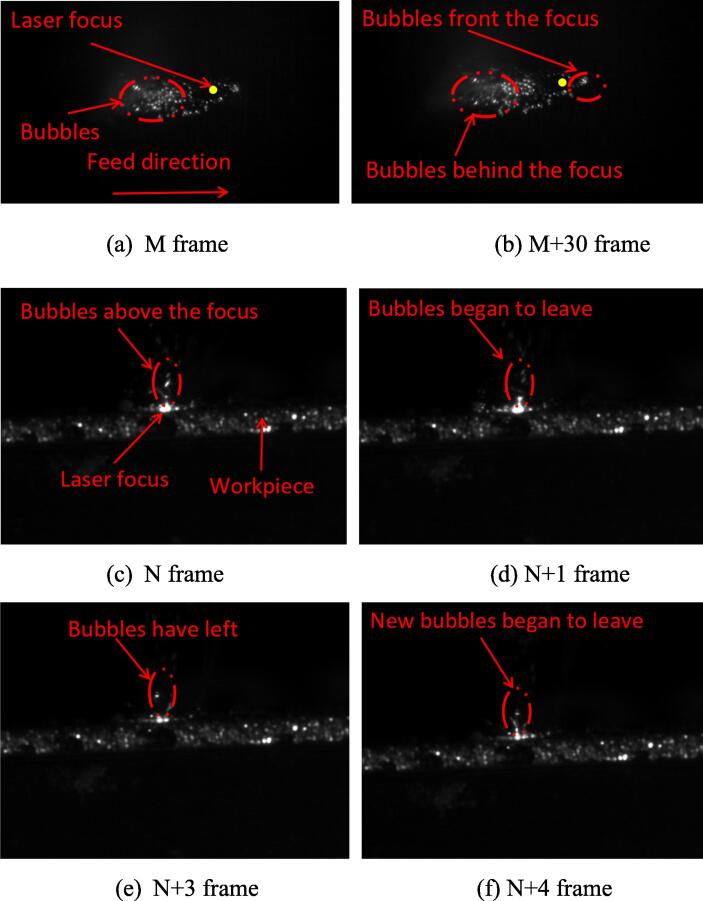

To avoid above problems, the bubble behavior needs to be further studied by observing the bubble behavior when machining silicon in LIPMM. An observation system is established equipped with a high speed camera, an optical filter (532 nm) and other accessories. Observations from two perspectives (front view and top view) are performed to comprehensively observe bubble behavior. The bubble behaviors from top view are shown in Fig. 10(a) and (b). It can be seen that most bubbles group behind the laser focus and continue to flow towards to the opposite direction of feed direction, which maybe result from the temperature and pressure difference between the laser focus and machined area. The generation of such numerous bubbles is maybe attributed to that the pulse laser overheats the materials and dielectric, resulting in the dynamic removal behavior of workpiece materials and the evaporation of dielectric fluid. Some micro cracks and indentations on the workpiece surface will provide adhesion points for bubbles nuclei, and then few bubbles can adhere in the front and on the side of the focus as shown in Fig. 10 (b). The bubbles adhered in the front or on the side of the focus hardly move, and a few small bubbles gradually congregated into a larger bubble, which an explosion occurs when this bubble exceeds the size threshold. This explosive behavior of bubbles will produce huge shock wave and explosive force in the local area, and this indicates that the bubbles adhered surrounding the laser focus will more likely damage the surface integrity. The explosion size of bubble (represented by its diameter db) depends on its internal pressure and the tension of the boundary surface between the bubble and dielectric fluid as expressed by [31]:

| (4) |

where σ is the tension, and pb is the internal pressure.

Fig. 10.

Bubbles images obtained by high speed camera on top view (a-b) and front view (c-f) by 10 kHz.

The bubble behavior on front view is also observed when the feed rate is set as 0.1 mm/s as shown in Fig. 10(c)-(f). It can be found that bubbles continue to rise and the floating speed is much faster than the feed speed of the laser focus, which is due to the buoyancy effect and temperature difference between laser path and surrounding medium. These floated upward bubbles will block the path of laser beam and scatter the laser beam, which affects the stability of the plasma and then damages the surface integrity.

Based on above analysis, it is evident that the bubbles adhered on the surrounding of the laser focus and floated upward will be harmful to the machined surface integrity. This gives us a direct understanding about the bubble behaviors, and using flow water maybe a good method to deal with the bubble problem, which will be further studied in our further work.

Conclusions

1. MC-LIPMM was proposed to process single-crystal silicon with small heat affected zone and good surface morphologies. Experimental studies revealed that magnetic field intensity and repetition frequency both had considerable impact on surface integrity including heat affected zone and surface morphologies. The heat affected zone and smooth surface morphologies can be decreased with maximum reduction of 12.64% under magnetic field of 0.1 T and repetition frequency of 10 kHz.

2. Magnetic field contributed to enhance the geometrical shape of the micro-channels by MC-LIPMM, resulting in maximum reduction of 62.57% for width as well as maximum increase of 26.23% for depth. The best aspect ratio of 5.857, increased by 90.26%, can be obtained under magnetic field intensity of 0.05 T and repetition frequency of 80 kHz.

3. An extraordinary scenario that the excessive bubbles severely adhere on the surrounding of the laser focus and rapidly float upward with an end to explosions was observed and analyzed. Since the bubble behavior perhaps blocks the path of laser beam and scatters the laser beam in the MC-LIPMM process, it negatively affects the stability of the plasma and then damages the surface integrity of single-crystal silicon.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant Nos. 51705171 and 51975228, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong No. 2020A151501638 and the program of China Scholarship Council (No.201806160076). This research is also supported by the Beijing Institute of Aeronautical Materials (BIAM). The authors would also like to thank Prof. Kornel F. Ehmann of Northwestern University for his contribution in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Wang M., Wang B., Zheng Y. Weakening of the anisotropy of surface roughness in ultra-precision turning of single-crystal silicon. Chin J Aeronaut. 2015;28(4):1273–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauener C.M., Petho L., Chen M., Xiao Y., Michler J., Wheeler J.M. Fracture of silicon: influence of rate, positioning accuracy, fib machining, and elevated temperatures on toughness measured by pillar indentation splitting. Mater Des. 2018;142(MAR.):340–349. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel S., Luo X., Agrawal A., Reuben R.L. Diamond machining of silicon: a review of advances in molecular dynamics simulation. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2015;88:131–164. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X., Liu C., Ke J., Zhang J., Shu X., Xu J. Subsurface damage and phase transformation in laser-assisted nanometric cutting of single crystal silicon. Mater Des. 2020;190 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ming W., Jia H., Zhang H., Zhang Z., Liu K., Jinguang D.u. A comprehensive review of electric discharge machining of advanced ceramics. Ceram Int. 2020;46(14):21813–21838. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rihakova L., Chmelickova H. Laser micromachining of glass, silicon, and ceramics. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2015;584952 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallav K., Han P., Ramkumar J., Ehmann K.F. Comparative assessment of the laser induced plasma micromachining and the micro-EDM processes. J Manuf Sci Eng. 2014;136(1) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng X., Yang L., Wang M., Cai Y., Wang Y., Ren Z. Laser beam induced thermal-crack propagation for asymmetric linear cutting of silicon wafer. Opt Laser Technol. 2019;120 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tangwarodomnukun V., Mekloy S., Dumkum C. Laser micromachining of silicon in air and ice layer. J Manuf Processes. 2018;36:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soltani B., Azarhoushang B., Zahedi A. Laser ablation mechanism of silicon nitride with nanosecond and picosecond lasers. Opt Laser Technol. 2019;119 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhihao F., Longfei C., Yingchun G., Hongyu Z. Picosecond laser micromachining of silicon wafer: characterizations and electrical properties. Surf Rev Lett. 2020;27(05):1950142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pallav K., Ehmann K.F.F. International Precision Assembly Seminar. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. Feasibility of Laser Induced Plasma Micro-Machining (LIP-MM) pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harilal S.S., Tillack M.S., O’shay B., Bindhu C.V., Najmabadi F. Confinement and dynamics of laser-produced plasma expanding across a transverse magnetic field. Phys Rev E. 2004;69(2) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.026413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhang G., Li W. Reduction of Energy Consumption and Thermal Deformation in WEDM by Magnetic Field Assisted Technology. Int J Precis Eng Manuf-Green Technol. 2020;7(2):391–404. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisarczyk T., Faryński A., Fiedorowicz H., Gogolewski P., Kuśnierz M., Makowski J. Formation of an elongated plasma column by a magnetic confinement of a laser-produced plasma. Laser Part Beams. 1992;10(4):767–776. [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanZeeland M., Gekelman W. Laser-plasma diamagnetism in the presence of an ambient magnetized plasma. Phys Plasmas. 2004;11(1):320–323. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begimkulov U.S., Bryunetkin B.A., Dyakin V.M., Koldashov G.A., Priyatkin S.N., Repin A.Y. Laser-produced plasma expansion in a uniform magnetic field. Laser Part Beams. 1992;10(4):723–735. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrokhi H., Gruzdev V., Zheng H.Y., Rawat R.S., Zhou W. Magneto-absorption effects in magnetic-field assisted laser ablation of silicon by UV nanosecond pulses. Appl Phys Lett. 2016;108(25) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrokhi H., Gruzdev V., Zheng H., Zhou W. Fundamental mechanisms of nanosecond-laser-ablation enhancement by an axial magnetic field. JOSA B. 2019;36(4):1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena I., Wolff S., Cao J. Unidirectional magnetic field assisted laser induced plasma micro-machining. Manuf Lett. 2015;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang H., Qiu P., Cao R., Zhuang J., Xu S. Repulsive magnetic field–assisted laser-induced plasma micromachining for high-quality microfabrication. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2019;102(5–8):2223–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy P.K. A first-order model for computation of laser-induced breakdown thresholds in ocular and aqueous media. I. Theory. IEEE J Quantum Electron. 1995;31(12):2241–2249. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi S. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester: 2005. Properties of Group-IV, III-V, and II-VI Semiconductors. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzidil’kovskii I.M. Nauka Publishers; Moscow: 1972. Electrons and Holes in Semiconductors. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J., Zhao L., Rosenkranz A., Song C., Yan Y., Sun T. Nanosecond pulsed laser ablation of silicon—finite element simulation and experimental validation. J Micromech Microeng. 2019;29(7) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulgakova N.M., Evtushenko A.B., Shukhov Y.G., Kudryashov S.I., Bulgakov A.V. Role of laser-induced plasma in ultradeep drilling of materials by nanosecond laser pulses. Appl Surf Sci. 2011;257(24):10876–10882. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlsson, E B. Solid State Physics - Solid State Physics (Second Edition). Solid State Physics, 2014.

- 28.Rockstroh T.J., Mazumder J. Spectroscopic studies of plasma during cw laser materials interaction. J Appl Phys. 1987;61(3):917–923. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charee W., Tangwarodomnukun V. Dynamic features of bubble induced by a nanosecond pulse laser in still and flowing water. Opt Laser Technol. 2018;100:230–243. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X., Huang Y., Xu B., Xing Y., Kang M. Comparative assessment of picosecond laser induced plasma micromachining using still and flowing water. Opt Laser Technol. 2019;119 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehrafsun S., Messaoudi H., Vollertsen F. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Nanomanufacturing. 2016. Influence of material and surface roughness on gas bubble formation and adhesion in laser-chemical machining; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]