In 2018, one-third of incident adult HIV infections in Kenya occurred among AGYW. [1,2] PrEP is approved as part of the national HIV prevention interventions.[3,4] AGYW have the lowest uptake of PrEP coupled with high discontinuation rates.[5–7] Sexually transmited infections are known to increase the risk of HIV acquisition.[8] Prevalence of STIs in sexually-active AGYW is high.[9] This drives health seeking behavior in this population and is a good opportunity to provide PrEP at point of care. We hypothesized that availing STI results would augment PrEP uptake among AGYW.

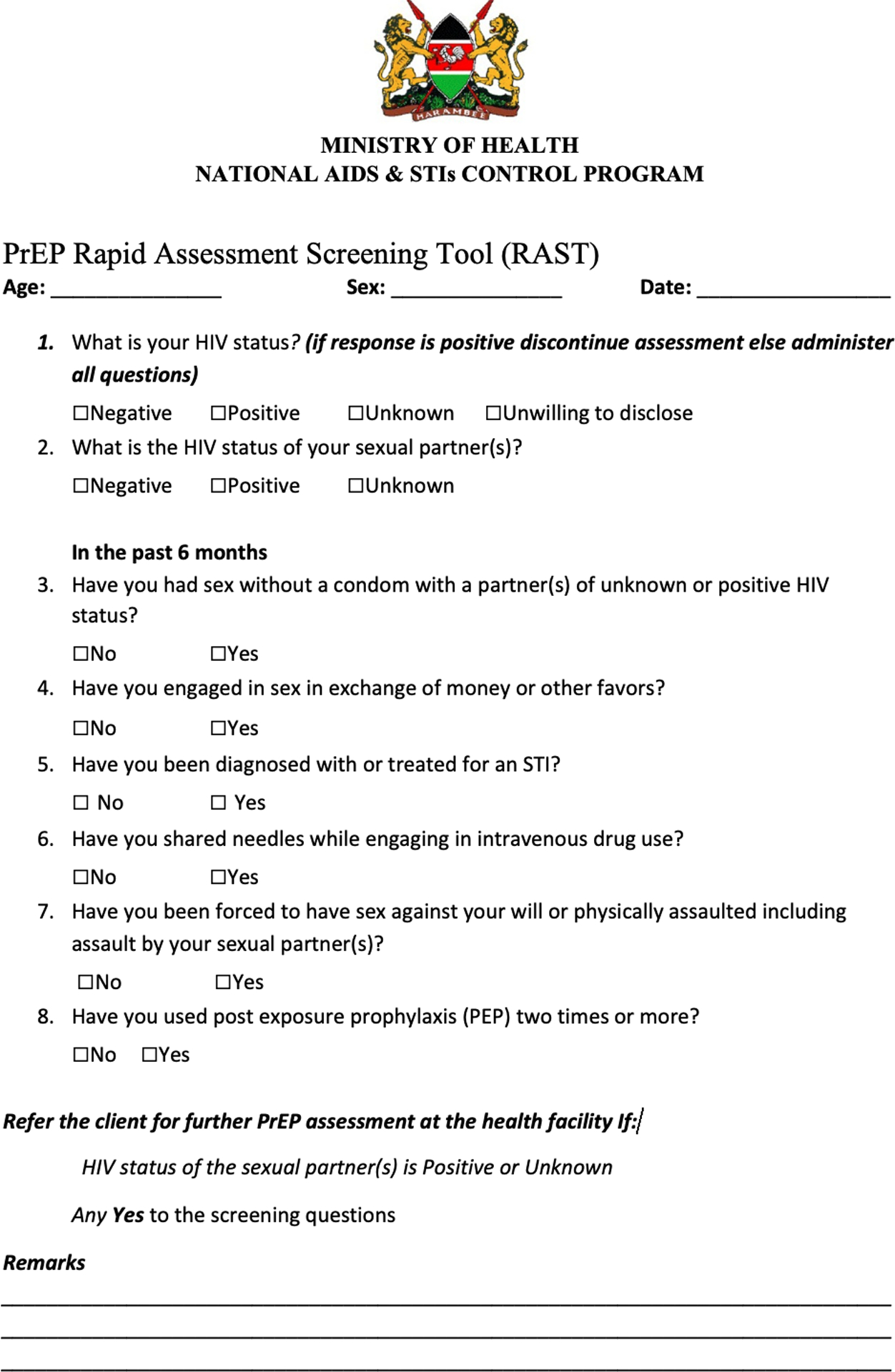

Participants were followed quarterly with STI testing for Neisseria gonorroheae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Trichomonas vaginalis.From January 2018 to December 2018, we screened for PrEP eligibility with a validated HIV risk assessment tool[Figure 1] which asks 7 questions to assess risk, and recommends PrEP for any “Yes” answers. PrEP uptake was defined as the number of girls initiating PrEP among those offered PrEP.[10] Chi-square testing was used to compare PrEP uptake with other variables.

Figure 1:

HIV risk assessment tool

Overall, 220 participants were assessed. PrEP knowledge was high, 179 AGYW (81.4%) reported having heard of PrEP but only 15/220 (6.8%) reported ever considering using PrEP. One hundred and sixty seven girls (76%) reported sexual debut and were assessed for HIV risk. Of 167 sexually-active participants, 119 (71.3%) reported inconsistent condom use and 20 (12%) had a confirmed STI. All at risk participants were offered PrEP on site; 9 (5.4%) accepted. Regardless of high HIV risk, 158 (94.6%) participants did not perceive themselves at risk and declined PrEP; 90 (57%) of the PrEP decliners reported inconsistent condom use in the 3 months prior to HIV risk assessment.

A higher proportion of AGYW with an STI diagnosis accepted PrEP 4/20(20%)compared to AGYW who were eligible for PrEP but without an STI diagnosis 5/147(3.4%).

There is a studied effort to evaluate PrEP delivery to AGYW in sub-Saharan Africa with ongoing demonstration projects: daily adherence reminders(m-health option), conditional cash transfers, bundling with reproductive health care and use of real-time electronic monitoring. Stigma remains a challenge, as many are not willing to admit that they may be at risk of HIV. Our work had some limitations. PrEP rollout was quite new at the time of this study, and AGYW may not have felt comfortable as early initiators. Participants took HIV tests quarterly and at this point most had received multiple negative HIV tests, which may have reinforced their self-perception of being low risk for HIV. Finally, the routine STI testing offered is unavailable in most settings, which may have limited understanding of the implication of an STI. In conclusion, we observed improved PrEP uptake in a group of AGYW when an STI diagnosis was made. Concrete evidence of risk, in the form of an STI diagnosis, might be an important factor in improving PrEP uptake.

Acknowledgements:

Source of Funding:

This research was funded by R01 HD091996-01 (ACR) from NICHD, by P01 AI 030731-25 (Project 2) (AW) and by the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), AI027757. We thank the participants. We thank CROI for scholarship funding that enabled us to present this data at the CROI Seattle 2019 conference. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Study data was collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Washington funded by UL1 TR002319, KL2 TR002317, and TL1 TR002318 from NCATS/NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflict of interest to disclose

References

- 1.National Aids Control Council (NACC). HIV estimates report 2018https://nacc.or.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/HIV-estimates-report-Kenya-20182.pdf

- 2.Kenya Population –Based HIV Impact Assessment (KENPHIA) REPORT. 2018 https://www.nascop.or.ke/kenphia-report/

- 3.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019Kenya Population and Housing Census. Volume III Distribution of Population by Age and Sex Socio-Economic Characteristics. https://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro=2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-iii-distribution-of-population-by-age-sex-and-administrative-units

- 4.Avert. Report on Young people HIV and AIDS 2016https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-social-issues/key-affected-populations/young-people

- 5.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AVAC. Kenya-PrEP Watch 2019https://www.prepwatch.org/country/kenya/

- 7.Mugwanya KK, Pintye J, Kinuthia J et al. Integrating preexposure prophylaxis delivery in routine family planning clinics: A feasibility programmatic evaluation in Kenya. PLOS Medicine 16(9): e1002885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corneli A, Wang M, Agot K et al. Perception of HIV Risk and Adherence to a Daily, Investigational Pill for HIV Prevention in FEM-PrEP JAIDS 2014. vol 67 issue 5 page 555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PrEP Watch. Options market intelligence report: Kenya. Key insights and communications implications for oral PrEP demand creation among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya. April2018https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/OPTIONS_AGYW_April2018.pdf

- 10.Cohen MS, Council OD, Chen JS. Sexually transmitted infections and HIV in the era of antiretroviral treatment and prevention: the biologic basis for epidemiologic synergy. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2019, 22(s6)e25355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]