Abstract

Experiencing and anticipating discrimination because one possesses a visible (e.g., race) or concealable (e.g., mental illness) stigmatized identity has been related to increased psychological distress. Little research, however, has examined whether experiencing and anticipating discrimination related to possessing both a visible and concealable stigmatized identity (e.g., a racial/ethnic minority with a history of mental illness) impacts mental health. In the current study, we test two hypotheses. In the first, we examine whether experienced discrimination due to a visible stigma (race/ethnicity) and anticipating stigma due to a concealable stigma (e.g., substance abuse) each predict unique variance in depressive symptomatology. In the second, we examine whether experienced discrimination due to a visible stigma is related to greater anticipated stigma for a concealable stigma, which in turn is related to more depression. A total of 265 African American and Latinx adults who reported concealing a stigmatized identity at least some of the time completed measures of racial/ethnic discrimination, anticipated stigma of a concealable stigmatized identity, and depressive symptomatology. Results of a simultaneous linear regression revealed that increased racial/ethnic discrimination and anticipated stigma independently predicted greater depressive symptomatology (controlling for each other). A mediation analysis showed that the positive association between increased racial/ethnic discrimination and higher depressive symptomatology was partially mediated by greater anticipated stigma. These results demonstrate that a person can experience increased psychological distress from multiple types of stigma separately, but also may anticipate greater stigma based on previous experiences of racial discrimination, which in turn relates to increased distress.

Keywords: Visible Stigma, Concealable Stigma, Anticipated Stigma, Discrimination, Depression

Experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination are related to increased psychological and physical distress (Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Schmitt, Branscombe, Postmes, & Garcia, 2014). Likewise, research on people with concealable stigmatized identities (CSIs) – identities that are not immediately apparent such as mental illness or substance abuse – has shown that greater anticipation of stigma if the identity were to be revealed is related to reports of greater psychological and physical distress (Ikizer, Ramírez-Esparza & Quinn, 2017; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). However, people possess multiple identities, and some may be visible while others are concealable. There are increasing calls within psychology to address how multiple identities impact each other (Bowleg, 2008; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016; Rosenthal, 2016) to shape people’s health outcomes (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). Yet, research rarely brings together experiences of both visible (e.g., race) and concealable (e.g., mental illness) stigmatized identities.

In the current work, we examined experiences of stigma in a sample of American adults who are racial/ethnic minorities (African American or Latinx) and who reported concealing a stigmatized identity at least some of the time. Thus, everyone in the sample possessed both a visible and concealable stigmatized identity. We measured people’s experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination, their level of anticipated stigma about their CSI, and their depressive symptomatology as a measure of mental health.

The current work was guided by two hypotheses. First, supporting work on the additive effects of possessing multiple disadvantaged statuses (e.g., Grollman, 2014), we predicted that both experienced racial/ethnic discrimination and anticipated CSI stigma would predict unique variance in depression. That is, more experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and more anticipated stigma would each predict higher levels of depressive symptomatology, controlling for the other. Second, we hypothesized that greater experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination would be related to more anticipated CSI stigma, which in turn would predict more depression. Our rationale is that experiencing discrimination of any kind will lead people to be more alert and concerned for future discrimination. This theorizing is in line with research examining how experiences of racial discrimination lead people to expect more racial discrimination in the future (e.g., Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). This prediction is tested in a mediation model with experienced racial/ethnic discrimination predicting greater anticipated stigma which, in turn, predicts depression. In sum, we hypothesize that experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination may be directly related to increased depression, but they may also be related to increased depression indirectly through the greater anticipation of CSI stigma. Note that these hypotheses are complementary and strive to illuminate a more complex picture of the lived experience of people with multiple stigmatized identities: A person can experience greater psychological distress from multiple types of stigma separately, but also can anticipate greater stigma based on previous experiences of discrimination with a different identity.

Sample and Method.

Participants were 265 self-identified African American (40.4%) and Latinx (59.6%) adults recruited to complete an in-person survey from three locations in and around Hartford, Connecticut, between 2009-2011 in exchange for $ - $20 (see Quinn et al., 2014) for full information on the recruitment procedure). All participants reported having at least one of five possible CSIs. Participants answered the anticipated stigma measure based on their reported CSI of substance abuse (26.4%), mental illness (25.3%), domestic violence (21.1%), childhood abuse (14.3%), or sexual assault (12.8%). If participants had multiple CSIs, they were asked to answer questions based on the identity that was most important to them.

On average, participants were in their thirties (M = 34.90, SD = 11.50), male (60.4%), low income (between $5,000 to $10,000 per year), and possessed a high school diploma or less (68%). The in-person survey was completed in English or Spanish (21%). All study procedures and measures were approved by an Institutional Review Board and the institutional review board of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) of the State of Connecticut.

Measures.

As part of the survey, participants completed measures of racial/ethnic discrimination, anticipated stigma of the CSI, and depressive symptomatology.

Racial/ethnic discrimination was measured using the 9-item “day-to-day” discrimination scale (Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams, 1999). The “day-to-day” discrimination scale assesses the frequency of experiencing different forms of racial/ethnic discrimination (e.g., “People act as if you are inferior”) from 0 (Never) to 4 (Often), α = .92, (M = 2.41, SD = .81).

Anticipated stigma of the CSI was measured using a 15-item anticipated stigma scale (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009) assessing the perceived likelihood of being mistreated if others were aware of their CSI (e.g., “Friends avoiding you”) from 1 (Very Unlikely) to 7 (Very Likely), α = .95, (M = 3.70, SD = 1.82).

Depressive symptomatology was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D assess the frequency of symptoms over the last week (e.g., “I felt fearful”) from 0 (Rarely or None of the Time [Less than 1 Day]) to 3 (Most or all of the Time [5–7 Days]), α = .87, (M = 1.21, SD = .58).

Sociodemographic characteristics were also measured and included as covariates in each analysis. Specifically, age in years, gender (0 =Male, 1 = Female), household income (1 = less than 5,000 to 12 = over 100,000), education (1 = Elementary School to 12 = Doctoral Degree), and language in which the survey was completed (1 = English, 2 = Spanish) were included as covariates.

Results.

As predicted, at the bivariate level more racial/ethnic discrimination was associated with more anticipated stigma of the CSI, r = .40, p <. 001 and higher depressive symptomatology, r = .27 p < 001. Consistent with previous research, more anticipated stigma of the CSI was associated with more depressive symptomatology, r = 31, p <. 001.

Additive model.

In order to examine whether racial/ethnic discrimination and anticipated stigma of the CSI uniquely and directly predict depressive symptomatology, we conducted a hierarchical multiple linear regression. Age, education, income, language, and gender were entered into the first step of the model and accounted for approximately 11% of the variance in depressive symptomatology, F (5, 248) = 7.15, p < .001. Including racial/ethnic discrimination into the model resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of variance accounted for in depressive symptomatology, ΔR2 .05, F (1, 247) = 14.35, p < .001, with a total of about 15% of the variance in depressive symptomatology accounted for when including racial/ethnic discrimination, F (6, 247) = 8.67, p < .001. Including anticipated stigma of the CSI into the final model also significantly increased the proportion of variance accounted for, ΔR2 = .03, F (1, 246) = 10.23, p= .002, with a total of 18% of the variance in depressive symptomatology accounted for when including anticipated stigma, F (7, 246) = 9,17, p < ,001, Importantly, in the final step of the regression, with all variables entered simultaneously, both experienced racial/ethnic discrimination, ß =.15, p = .019, and anticipated stigma, ß = .21, p = .002, were significant and unique predictors of depressive symptomatology. Thus, as predicted, these results give support for an additive model of stigma, with each type of stigma accounting for unique variance in depression.

Mediation model.

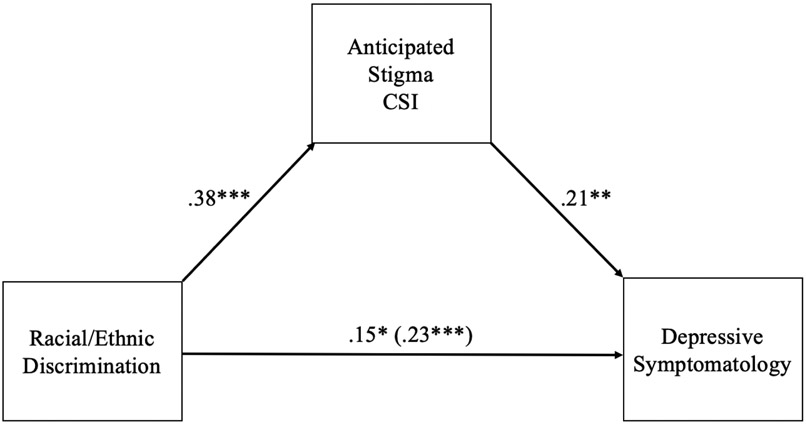

In order to examine whether the relationship between experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination and depression is partially mediated through a greater anticipation of stigma around one’s CSI, we conducted a simple mediation analysis using 5,000 bootstrapped confidence intervals to test the statistical significance of the indirect effect (Hayes, 2017). As seen in Figure 1, results revealed that racial/ethnic discrimination indirectly predicted depressive symptomatology through its relationship with anticipated stigma of the CSI even when accounting for the covariates, ß = .08, 95% CI [.03, .14]. Specifically, the more racial/ethnic discrimination African American and Latinx adults experienced, the more likely they believed that they would be mistreated if others were to become aware of their CSI, ß = .38, p <.001, 95% CI [.26, .50], which in turn was associated with higher depressive symptomatology, ß = .21, p = .002, 95% CI [.08, .33]. The direct effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on depressive symptomatology remained significant even when accounting for anticipated stigma of the CSI and all of the covariates, ß = .15, p =.02, 95% CI [.03, .28], demonstrating that the indirect path through greater anticipated stigma was one way that experiences of discrimination relate to depression but not the only way.

Figure 1:

Standardized regression coefficients for the effect of racial/ethnic discrimination on depressive symptomatology through anticipated stigma of a concealable stigmatized identity, controlling for age, gender, household income, education, and language in which the survey was completed. The total effect shown in parentheses. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

In the current work we considered how the experiences and beliefs related to visible and concealable identities may work separately and together to impact mental health. Consistent with past research on multiple disadvantaged statuses (e.g., Grollman, 2014), more experienced racial/ethnic discrimination and more anticipated stigma regarding a CSI, independently predicted greater depressive symptomatology. We also tested a novel hypothesis that experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination may predict anticipated stigma with a concealable stigmatized identity, which builds on past research about expectations of future discrimination (Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002). Our findings suggest that the relationship between experienced racial/ethnic discrimination and depressive symptomatology was partially mediated by anticipated stigma of a CSI—specifically, more experienced racial/ethnic discrimination predicted more anticipated stigma of a CSI, which, in turn, predicted more depressive symptoms (i.e., worse mental health). That the mediation was partial instead of full highlights that the relationships between multiple identities and depression are working along both separate and enmeshed pathways.

Findings from the current research suggest that experiences of discrimination with a visible stigmatized identity can sensitize a person to anticipate more stigma based on a concealable identity. It could be that once someone has experienced discrimination because of their race/ethnicity, they then come to expect poor treatment from others based on other social identities. Although this theorizing is in line with research examining how experiences of racial discrimination lead people to expect more racial discrimination in the future (e.g., Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002), the current work is cross-sectional. We believe it is likely that experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination occur before the acquisition of the concealable stigmatized identities (Cheng, Cohen, & Goodman, 2015), but a longitudinal study that includes both experiences of discrimination and anticipation of discrimination based on multiple identities is needed to provide stronger evidence of a temporal pathway.

Another way to examine the relationship between multiple identities is to examine whether they statistically interact. For example, people who have high levels of experienced racial discrimination might report different levels of depressive symptomology depending on whether they have high or low levels of anticipated stigma. That is, scores on one variable may moderate the relationship between scores on the other variable and the outcome. We tested for such a statistical interaction using Hayes (2017) PROCESS model and found it was not supported, b = .06, p = .30, 95% CI [−.05, .16].

People live with multiple identities. In order to understand how social identities affect health, it is crucial for researchers to begin collecting information not only on whether a person possesses multiple identities, but also their experiences of disadvantage related to those identities. This study, focusing on measures of experienced and anticipated discrimination of visible and concealable stigmatized identities is a small step in that direction. Combined with a greater understanding of institutional and structural sources of discrimination, researchers can get closer to a full picture of how stigma contributes to health disparities (Hatzenbueler et al., 2013), and, ultimately, to know where the best places to intervene to improve health are.

References

- Bowleg L (2008). When Black + Lesbian + Woman ≠ Black Lesbian Woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59, 312–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ER, Cohen A, & Goodman E (2015). The role of perceived discrimination during childhood and adolescence in understanding racial and socioeconomic influences on depression in young adulthood. Journal of Pediatrics, 166, 370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest N, & Hyde JS (2016). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II methods and techniques. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 70(3), 319–336. doi: 10.1177/0361684316647953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA (2014). Multiple disadvantaged statuses and health: The role of multiple forms of discrimination. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(1), 3–19. doi: 10.1177/0022146514521215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, PhD, Phelan JC, PhD, & Link BG, PhD. (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5) 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ikizer EG, Ramírez-Esparza N, & Quinn DM (2018). Culture and concealable stigmatized identities: Examining anticipated stigma in the united states and turkey. Stigma and Health, 3(2), 152–158. doi: 10.1037/sah0000082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the united states. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40(3) 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, & Pietrzak J (2002). Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students' college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4) 896–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman L (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059; (Supplemental) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Williams MK, Quintana F, Gaskins JL, Overstreet NM, Pishori A, Earnshaw VA, Perez G, & Chaudoir SR (2014). Examining effects of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, internalization, and outness on psychological distress for people with concealable stigmatized identities. PLoS One. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, & Chaudoir SR (2009). Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal L (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71(6), 474–485. doi: 10.1037/a0040323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt MT, Branscombe NR, Postmes T, & Garcia A (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]