Abstract

Objective:

Many clinicians find it challenging to obtain training in evidence-based interventions, including behavioral parent training, which is considered the front-line treatment for children with disruptive behaviors (Chacko et al., 2017). Workshops, ongoing consultation, and feedback provided in person are effective, yet are rarely feasible for clinicians in the field (Fixsen, Blase, Duda, Naoom, & Van Dyke, 2010). The purpose of the present study was to conduct a preliminary assessment of an online tutorial combined with live remote coaching for training mental health professionals in behavioral parent training.

Method:

Participants in this pretest-posttest open trial were 22 clinicians and graduate students (73% female) from around the United States.

Results:

The web platform operated successfully, and clinicians found the training to be highly satisfactory. Compared to pre-training, participants demonstrated large improvements in knowledge about disruptive behavior and behavioral parent training and performed significantly better on demonstrations of skill in administering behavioral parent-training components.

Conclusions:

An online course combined with live remote coaching is a promising methodology for significantly increasing the number of clinicians trained in evidence-based interventions for disruptive behavior in children. Next steps for evaluation and expansion of this training model are discussed.

Keywords: Behavioral Parent Training, Disruptive Behavior, Online, Training, Evidence Based, Dissemination

Child-onset disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) are characterized by oppositional and defiant behaviors, impulsivity, and aggression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Young children with behavioral challenges incur considerable costs to society (Moffit et al., 2002; Rivenbark et al., 2018). These children are at high risk for continued conduct problems and antisocial problems well into adolescence and adulthood (Babinski, Hartsough, & Lambert, 1999; Lee & Hinshaw, 2004; Mordre et al., 2011; Sibley et al., 2011). Recently, Galan et al. (2019) conducted a follow-up study of young children through adolescence and adulthood and found that early onset behavioral challenges were predictive of violent behavior in adolescence and adulthood, adolescent correlates of antisocial behavior, and internalizing problems in adulthood. This study further found that those children with chronic, early problems were at highest risk for multiple types of difficulties during adolescence and adulthood including violent behavior, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Similarly, Rivenbark et al (2018) found that while young children with early-onset and chronic behavioral problems account for only nine percent of the population, they account for approximately 53% of criminal convictions, 16% of emergency department visits, and 20% of medical prescriptions in adulthood. These data point to the early childhood period as an important window of opportunity to intervene in the lives of young children with behavioral problems.

Behavioral parent training (BPT) is the most well-studied and efficacious psychosocial intervention for school-aged children with DBDs (Chacko et al., 2017). This intervention is based on social interaction theory, which suggests that parents and children engage in a coercive cycle where both escalate their aversive behavior until one party gives in, which reinforces child noncompliance as well as ineffective parenting techniques (Granic & Patterson, 2006; Patterson, 1982). In BPT, parents and caregivers are taught to lessen the intensity of this coercive cycle by using reinforcement and limit setting skills to simultaneously reduce misbehavior while increasing incompatible “positive-opposite” behavior. Core skills taught include praise, play, direct commands, and time out (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009). Implementation of BPT as a first-line intervention is critical in order to improve the lives of youth with DBDs and reduce familial and societal burden (Kaminski & Claussen, 2017).

Graduate programs increased emphasis on evidence-based interventions (EBIs) and state requirements for and availability of continuing education courses, have led to increased opportunities for training in EBIs. However, data suggest that graduate school training in EBIs for childhood psychiatric disorders is relatively rare when compared to adult-focused EBIs (Pidano & Whitcomb, 2012). Moreover, while individual training elements (i.e. didactics, ongoing consultation, and feedback) are often utilized in graduate training, their combination, which is considered best practices, (Edmunds Beidas, & Kendall, 2013; Herschell et al., 2010) is less common. Continuing education courses typically focus on didactics and immediate hands-on practice (role plays) but are rarely individualized and ongoing consultation is not often provided. However, having consultants physically available for training and ongoing consultation is not typically feasible, due in large part to funding and time constraints (Fixsen, Blase, Duda, Naoom, & Van Dyke, 2010).

New technologies provide opportunities to increase the accessibility of high-quality training (Barnett, 2011; Kazdin & Blasé, 2011). In particular, online clinician training offers several advantages to traditional methods, including 24-hour access, customization (e.g., selfpaced, allowing for repetition and review), opportunity for interactive exercises and multimedia training components (audio, video, animation, etc.), all of which have been shown to enhance knowledge retention (Khanna & Kendall, 2015; Zhang, 2005). Research has found that using interactive, web-based tutorials combined with live remote coaching can significantly improve therapeutic skills (Kobak, Opler, & Engelhardt, 2007) and knowledge (Brennan, Sellmaier, Jivanjee, & Grover, 2018).

The purpose of the present pilot study was to develop and test a technological platform for training mental health professionals in BPT. This training is innovative in that it paired an online tutorial on BPT’s theoretical principles and four core skills (i.e., praise, play, commands, and timeout) with live remote coaching and role-plays with a trainer in order to maximize participant knowledge and skill acquisition. This project is significant because there is a general dearth of research on the efficacy of online training of psychological interventions and in particular, despite their increasing usage, little data exist on the efficacy of hybrid training models. Finally, and perhaps most important, no web-based therapist training course that combines these two components and focuses specifically on BPT for disruptive behavior disorders has been tested. The aspects of individualization of the training, immediate tailored feedback, and ongoing consultation are essential to the training intervention that we have developed and offers a distinct opportunity for both students and clinicians. Pilot studies, such as this one, are crucial first steps toward evaluating whether these training models can lead to markedly higher penetration rates of evidence-based practice.

The aims of the study were to evaluate whether the web platform operated successfully, participants found the content satisfactory, and participants’ knowledge of BPT principles and skill improved. Finding preliminary evidence that our training is feasible and acceptable would serve as a first step toward increasing dissemination of BPT training to mental health professionals, thereby increasing treatment availability for parents of children with disruptive behaviors. Initial findings suggesting we can improve clinicians’ ability to conduct BPT would also lend support for conducting a larger trial to determine if clinicians who received the training could demonstrate improved outcomes in their clients’ parenting skills, as well as improvements in their clients’ children’s disruptive behaviors.

Method

Participants

As shown in Table 1, the 26 participants who enrolled and provided consent were primarily female (n = 19, 73.1%), white (n = 21, 80.8%) and 29.7 years of age on average (SD = 7.3 years). Half had a bachelor’s degree (n = 13), seven (26.9%) had a doctoral-level degree (Ph.D. or Psy.D.) and six (23.1%) had a master’s degree. The sample had, on average, 4.15 years (SD = 5.82) of clinical experience, and 16 participants (61.5%) were enrolled in graduate school at the time of the study. The majority of the sample (n = 20, 76.9%) had no prior, formal training in BPT.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Age | M (SD) | n, % |

|---|---|---|

| 29.7 (7.3) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 19, 73.1% | |

| Male | 7, 27.0% | |

| Self-Identified Race | ||

| White | 21, 80.8% | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1, 3.8% | |

| Black or African American | 1, 3.8% | |

| Other | 3, 11.5% | |

| Hispanic Identity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 25, 96.2% | |

| Hispanic | 1, 3.84% | |

| Currently in Graduate School | ||

| Yes | 16, 61.5% | |

| No | 10, 38.5% | |

| Highest Educational Degree | ||

| Bachelors | 13, 50% | |

| Masters | 6, 23.1% | |

| Doctoral (Ph.D., Psy.D.) | 7, 26.9% | |

| Total Years of Experience Conducting Psychotherapy | 4.15 (5.82) | |

| Prior Formal Training in Behavior Parent Training | ||

| No | 20, 78.9% | |

| Yes | 6, 23.1% |

Procedure

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study and recruitment occurred between 1/30/2018 and 6/28/2018. Potential participants were recruited through professional listservs and by email announcements to clinical psychology doctoral students at Long Island University Post and New York University. Interested individuals contacted a designated member of the investigative team who determined eligibility and secured informed consent via electronic signature. Eligibility criteria included adults who were practicing clinicians or graduate students in psychology or social work.

Thirty-one people expressed interest in participating in this pretest-posttest open trial and signed consent forms allowing us to send them links to pre-training assessments. Of that number, 26 people completed pretest assessment materials and began the online tutorial. Twenty-two participants completed the online tutorial and 21 subsequently met with a BPT trainer for three video conference coaching sessions (one participant who completed the online tutorial did not complete the coaching sessions or the posttest).

Pre and Post-Training Assessment of Didactic Knowledge and Clinical Skills.

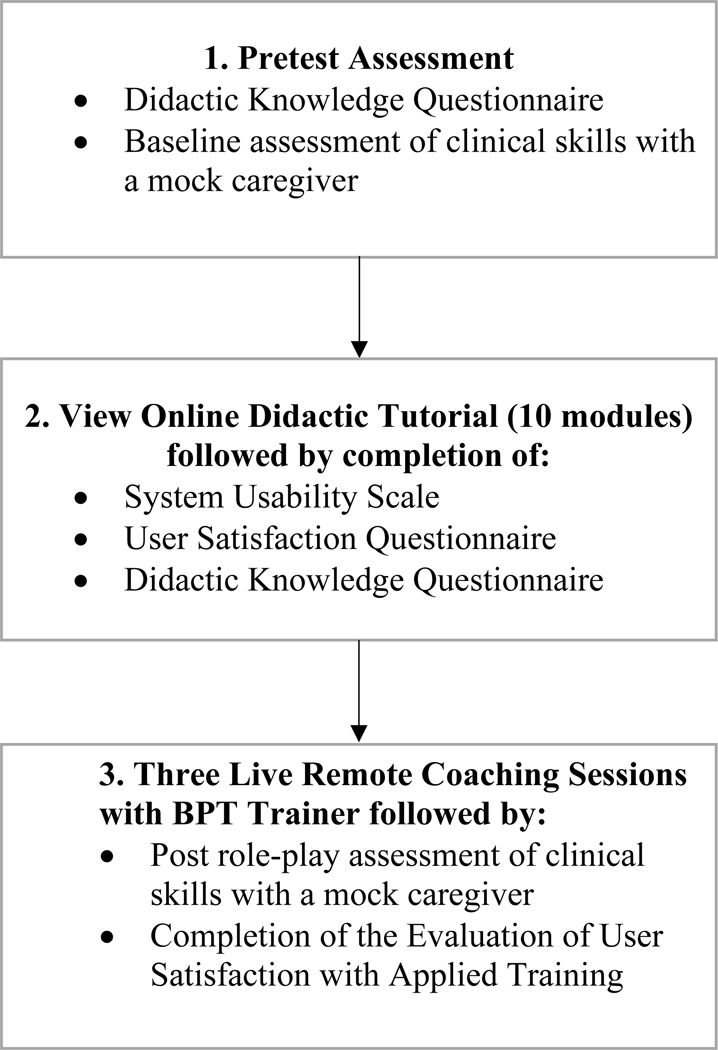

As shown in Figure 1, once enrolled, but before accessing the online materials, participants completed the Didactic Knowledge Questionnaire on their knowledge of BPT concepts and principles. We also assessed their clinical skills in conducting BPT with a mock caregiver, who was a member of the research team. Since trainees were in diverse areas of the country, a web-based interface (Zoom) was used to conduct and record the pre- and post-test of trainee clinical skills. During these video recorded role-plays, participants were asked to describe the theory underlying four BPT skills (nondirective play, praise, time out, and commands), teach the components of each skill to the mock caregiver, and role play administering the skills as if the participant was the caregiver of a child with a DBD (the trainer played a mock child). Each pretest (and subsequent posttest) assessment video of clinical skill was edited by a single member of the research team to remove all evidence of whether it occurred before or after the training. For example, if a research participant remarked that it was nice to see the research team member again, that segment of the video was deleted. Videos were then randomly assigned to the other research team members, who were blind to pretest or posttest recording status. Each video was scored by a single research team member with the BPT skills checklist and the adapted FIMP (Fidelity of Implementation Rating System) continuous rating (descriptions below). Before videos were scored, team members had practiced on mock video segments. Given the structure of the FIMP and the BPT skills checklist, research team members quickly converged on a high level of interrater reliability (all research team members obtained Cohen’s Kappas and intraclass correlation coefficients of >.8 for BPT skills checklists and FIMP ratings respectively) before scoring videos used for data analysis.

Figure 1:

Participant Procedure

After completion of the pretest assessment of knowledge and the role-play, participants were sent a link to access the online tutorial. After completion of the online tutorial, participants completed the System Usability Scale (SUS) and User Satisfaction Questionnaire (USQ) (descriptions below) and once again completed the Didactic Knowledge Questionnaire. They then engaged in three live video conference practice coaching sessions (described in the next section) with a BPT trainer who was the same individual who served as the mock caregiver in the pretest. Once the live coaching sessions were completed, the participant completed a posttest role-play assessment identical to the pretest assessment with the same BPT trainer who again served as a mock caregiver. Participants also completed the Evaluation of Applied Training Scale (EATS) (description below) measure of satisfaction with the live training.

Online Didactic Tutorial.

The online tutorial contained 10 modules covering the theoretical principles underlying BPT, key features on each of the four skills covered (labeled praise, positive play, commands, and timeout) and how to effectively teach these skills to caregivers (see on-line Appendix A for a complete description of course content and learning objectives). We determined which BPT skills to include in the online tutorial by reviewing efficacious BPT manuals for parents of young children and selecting skills practiced commonly across these interventions. Second, we compared our list to a study that used a distilling and matching model to determine common practice elements across randomized child treatment trials, including those focused on child behavior problems (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009). In line with BPT manuals, praise was defined as rewarding a child with verbal and nonverbal approval as a method of reinforcing target behaviors. Participants learned the rationale for emphasizing praise over punishment as well as strategies for effectively praising children (e.g., praising immediately after a target behavior). Play focused on a set of strategies (e.g., reflecting a child’s words, avoiding commands and questions) for shifting caregiver attention from unwanted behaviors to those they wished to increase, as well as improving the quality of caregiver-child interactions. Participants were also taught how to help parents effectively structure playtimes and ignore undesired behaviors. Commands were defined as prompts designed to elicit child compliance, followed by contingent reinforcement. Finally, a time out from reinforcement was taught as a more effective punishment procedure than corporal punishment strategies. Participants learned how to identify target behaviors for time out, the sequence of steps to follow to carry out the procedure effectively, and how to handle child noncompliance during time out.

Studies have found that high levels of interactivity, multi-model learning and ongoing self-tests enhance knowledge retention in on-line training (Brennen et al, 2018). Thus the tutorial contains interactive exercises, animated graphics, ongoing interactive self-tests, and video examples of techniques in a multimodal, multimedia, interactive learning approach (please visit http://telepsychology.net/BPT_Default.aspx to access the on-line tutorial).

Live Remote Coaching.

Since didactic training alone is insufficient for acquiring new clinical skills, providing an opportunity for trainees to practice applying these skills was a critical component of the training (Washburn et al 2019). The primary goal of the 60-minute coaching sessions was to reinforce knowledge learned in the tutorial and provide opportunities to model and role-play the use of the skills. To do this, the trainer pretended to be a parent seeking help with a disruptive child and the research subject acted as the therapist. Session 1 focused on praise and play, session 2 on commands and time out, and session 3 was flexible, allowing each trainer and participant pair to determine what content was most important to discuss and practice. In sessions 1 and 2, trainers asked if the participants had questions about the skill and then asked how the participant thought the skill fit within an operant conditioning/social learning model and helped to clarify their understanding. Participants were encouraged to discuss how the skill fit with other previously discussed skills (e.g., how does time out fit with praise within an operant conditioning/social learning model). Next, trainers focused on three components: the rationale for each skill, how to teach caregivers each skill, and how to roleplay each skill with caregivers. Participants were taught the rationale for each skill in order to learn how to explain the purpose of the skill to caregivers, which would likely increase buy in. They then learned how to teach caregivers didactics on specific components of each skill, to ensure they could thoroughly describe each step of the skill to clients. Finally, they learned how to roleplay to provide caregivers with the opportunity to see each skill modeled before rehearsing it themselves. For example, in this final part, trainers pretended to be a disruptive child and research participants were taught to put the child (trainer) into time out. In session 3, trainers answered any remaining questions, and asked participants to describe the rationale of all of the skills in an integrated way. The bulk of the session was then spent modeling and roleplaying the nuances of skills. Skills were typically practiced with some increased challenges (e.g., time out with a child refusing to go to time out).

Measures

User Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Satisfaction with the web-based tutorial’s clinical content was evaluated using the User Satisfaction Questionnaire (USQ; Kobak, Reynolds, & Griest, 1994). The USQ is a self-report measure that contains eight statements pertaining to whether participants found the training to be interesting, easy to understand, enjoyable, useful/relevant, and satisfactory. Users rated their satisfaction on a 4-point scale (strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree). The scale ranges from 8 to 32, and has good internal consistency (Kobak, Lipsitz, Markowitz, & Bleiberg, 2017).

System Usability Scale.

Satisfaction with the technical aspects of the web-based tutorial was assessed with the 10-item System Usability Scale (SUS; Bangor, Kortum, & Miller, 2008; Brooke, 1996). The SUS is a reliable, well-validated measure designed to evaluate usability and user satisfaction with web-based applications and other technologies. On a 0–100 scale, a SUS score greater than 50.9 (mean rating for systems considered “Okay”) is considered evidence of system user-friendliness (Bangor et al., 2009) (see Appendix B for a copy of the SUS).

Evaluation of User Satisfaction with Applied Training.

The Evaluation of Applied Training Scale (EATS) was used to evaluate satisfaction with the live coaching. It assessed trainees’ perspectives on how much they learned from the live training, their self-assessed competence on the various skills covered, and their level of satisfaction with live training components. The EATS has been used previously in studies of live online training (e.g. Kobak, Wolitzky-Taylor, Craske, & Rose, 2016) (see Appendix C for a copy of the EATS).

Didactic Knowledge Questionnaire.

To assess changes in participants’ knowledge of BPT concepts and principles (causes of noncompliance, operant conditioning, praise, play, commands, time out), participants completed a 54-item, multiple-choice questionnaire created by the investigators before and after completing the online tutorial. Each item tests participants understanding of key critical concepts covered in the tutorial.

BPT Skill Checklist.

To assess change in skill at delivering BPT content, 13 videos were taken of each participant role-playing with trainers both before they accessed the online tutorial and again, after they had completed both the online tutorial and live coaching. Three videos were recorded for each of the four parenting skills, (explaining the rationale for the skill to a parent, teaching a parent the steps involved in implementing the skill, demonstrating how to role-play the skill with a parent). The timeout skill included a fourth video on how to role-play handling noncompliance with timeout. Trainees’ pre and post-training videos were blindly evaluated using the BPT Skills Checklist (please see Appendix D for a copy of the checklist), which assessed the key points they were expected to address in each of the role-plays for each skill. Play included the largest number of key points (n = 29), followed by timeout (n = 27), praise (n = 24), and commands (n = 14).

Adapted Fidelity of Implementation Rating System.

Participants’ pre and post-training videos were also blindly rated using an abbreviated form of the Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP; Knutson, Forgatch, Rains, & Sigmarsdóttir, 2009). The FIMP is a coding system that was created to measure therapists’ adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training (PMTO; Forgatch, 1994) along five dimensions: Knowledge, Structure, Teaching, Process Skills, and Overall Development. Scores on the FIMP have been found to predict parent-training outcomes, such as improvement in children’s disruptive behavior (Thijssen, Albrecht, Muris, & de Ruiter, 2017). The FIMP is typically used to evaluate sections of BPT sessions that span 10 minutes or more. Given that the segments that were rated in the present study were much shorter (often two minutes or less) and were role-plays of specific skills, some of the items on the FIMP did not apply. For example, the original FIMP assesses how well practitioners explain homework assignments to clients, which did not apply in our case. We primarily used the knowledge and teaching subscales of the FIMP. Investigators rated each of the thirteen pre-training and post-training role-plays on a 9-point Likert scale. As on the original FIMP, scores between 1–3 were categorized as “needs work,” scores between 4–6 were categorized as “acceptable,” and scores between 7–9 were categorized as “good work.” The mean scores for each parenting skill were computed by adding the three FIMP ratings (rationale, teaching, and roleplay) and dividing by three.

Results

Satisfaction.

Satisfaction with the clinical components of the online tutorial was assessed with the USQ. As shown in Table 2, on a scale from one to four, with one signifying strongly disagree and four signifying strongly agree, participants were satisfied with the online tutorial overall (M = 3.46, SD = .67) and would recommend it to others (M = 3.5, SD = .67). Participants found the online content interesting (M = 3.36, SD = .73), easy to understand (M = 3.73, SD = .46), enjoyable (M = 3.5, SD = .67), and useful/relevant in teaching them to help parents with noncompliant children (M = 3.68, SD = .48). While still high, participants were less enthusiastic about their ability to apply these skills to clients (M = 3.23, SD = .43). This was expected as the rating was made prior to live coaching and one of the reasons for adding live coaching to the online content. Relating to the technical components of the online tutorial, participants rated the “System Usability” score for the online tutorial as 86.7, which is between ‘excellent’ and ‘best imaginable.”

Table 2.

USQ Mean Satisfaction Ratings of Online Tutorial

| Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| 1. The material was presented in an interesting manner | 3.4 (0.72) |

| 2. The concepts were clearly presented and easy to understand | 3.7 (0.46) |

| 3. I would recommend this course to others | 3.5 (0.67) |

| 4. I enjoyed taking this tutorial | 3.4 (0.67) |

| 5. The content was useful and relevant in teaching me how to help parents with non-compliant children | 3.7 (0.48) |

| 6. I feel able to apply these skills with clients | 3.2 (0.43) |

| 7. How satisfied were you with this tutorial? | 3.5 (0.67) |

Note: Items 1–6, Scale 1= strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree Item 7: 1 = very dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = satisfied, 4 = very satisfied.

With respect to the live coaching, scores on the EATS indicated that overall satisfaction was high (M = 3.81, SD = .40). Trainees reported that the live coaching enhanced their professional expertise (M = 3.81, SD = .40) and facilitated answering their questions (M = 3.95, SD = 2.2). This rating was also on a scale from one to four, with one signifying strongly disagree and four signifying strongly agree. Similarly, as shown in Table 3, trainee’s self-ratings of competence in using the four core BPT skills was low before training, ranging from 2.2–2.8 (on a scale where 1 equaled “very little” and 5 equaled “a great deal”) and high after training, ranging from 4.3–4.6. All four mean ratings were significantly higher at posttest than at pretest with very large effect sizes.

Table 3.

Mean Ratings of Self-Assessed Competency on Behavioral Parent Training Skills Pre- and Post-Training (N = 21)

| Skill | Mean (SD) Pre-training |

Mean (SD) Post-training |

t | p | Effect Size (d) |

95% CI for Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praise | 2.8 (1.4) | 4.6 (0.5) | 6.86 | < .001 | 1.71 | [2.36, 1.26] |

| Play | 2.3 (1.3) | 4.5 (0.5) | 8.3 | < .001 | 2.09 | [2.61, 1.56] |

| Commands | 2.5 (1.4) | 4.5 (0.5) | 7.8 | < .001 | 1.90 | [2.47, 1.42] |

| Time Out | 2.2 (1.0) | 4.3 (0.5) | 10.8 | < .001 | 2.65 | [3.23, 2.19] |

Note: Question worded “How competent do you feel applying the following skills with parents?” Scale 1 = very little, 5 = a great deal

Knowledge.

Mean scores on the Didactic Knowledge Questionnaire evaluating trainee knowledge of the theory and practice of BPT at posttest (M = 40.36, SD = 4.93) were significantly higher than at pretest (M = 21.82, SD = 4.03, t = 18.24, p <.001). The effect size of the difference was very large (Cohen’s d = 3.889). As shown in Table 4, after completing both training components, applicants rated their knowledge of the rationale for each of the four parenting skills and the practical steps for teaching each skill as very high, with mean scores for each rating reaching almost the top score of 5, which corresponded to “a great deal.”

Table 4.

Mean Self Ratings on the Evaluation of Applied Training Scale (EATS)

| Item | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| 1. How much did you learn as a result of the applied training sessions? | 4.3 (0.73) |

| 2. How well do you understand the theoretical rationale for: | |

| Praise | 4.9 (0.36) |

| Positive play | 4.9 (0.37) |

| Commands | 4.8 (0.41) |

| Time out | 4.9 (0.37) |

| 3. How well do you understand the steps required to implement the following skills: | |

| Praise | 4.9 (0.22) |

| Positive play | 4.8 (0.44) |

| Commands | 4.8 (0.41) |

| Time out | 4.7 (0.47) |

Note: Scale 1 = very little, 5 = a great deal

Skill.

Using the BPT checklist, we rated participants’ skills on a series of structured role-plays at pretest and after participants had finished both online tutorial and remote coaching. Before training, out of 96 possible points, the average participant demonstrated 27.4 skills (SD = 14.2) and after training, the average score was 59.6 skills (SD = 12.6). The difference in means was statistically significant (t = 9.4, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 2.4). As shown in Table 5, ratings of each of the four skills also showed statistically significant improvements from pretest to posttest with very large effect sizes. Similarly, as shown in Table 6, blind continuous ratings of skill, using the adapted FIMP scale revealed statistically significant improvements on observed skill in using all four BPT domains (ps all <.001), with very large effect sizes.

Table 5.

Mean Number of Therapist Skills Demonstrated on Checklist of Trainee Behaviors Pre- and Post-Training (N = 21)

| Skill | Mean (SD) Pre-training |

Mean (SD) Post-training |

t | p | Effect Size (d) |

95% CI for Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praise | 6.0 (3.1) | 13.6 (3.6) | 8.6 | < .001 | 2.23 | [2.77, 1.69] |

| Play | 7.3 (5.7) | 18.2 (6.0) | 8.1 | < .001 | 1.92 | [2.42, 1.43] |

| Commands | 5.0 (2.2) | 11.3 (0.5) | 9.9 | < .001 | 2.69 | [3.46, 2.26] |

| Time Out | 9.0 (5.3) | 16.2 (4.5) | 4.7 | < .001 | 1.46 | [2.11, .80] |

| Total Score | 27.4 (14.2) | 59.6 (12.6) | 9.4 | < .001 | 2.40 | [2.94, 1.87] |

Note: Number of total checklist skills assessed = 94 (Praise = 24, Positive Play = 29, Commands = 14, Time Out = 27)

Table 6.

Mean Adapted Fidelity of Implementation Rating System Scale (FIMP) Scores, Pre- and Post-Training (N = 21)

| Skill | Mean (SD) Pre-training |

Mean (SD) Post-training |

t | p | Effect Size (d) |

95% CI for Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Praise | 3.3 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.5) | 4.9 | < .001 | 1.38 | [0.81, 1.96] |

| Play | 3.1 (2.1) | 5.7 (1,7) | 5.1 | < .001 | 1.39 | [0.81, 1.97] |

| Commands | 3.5 (1.6) | 6.6 (1.5) | 5.8 | < .001 | 1.99 | [1.31, 2.76] |

| Time Out | 2.9 (1.8) | 5.3 (2.1) | 3.5 | < .001 | 1.22 | [0.52, 2.00] |

Note: FIMP skill scale range 1–9; FIMP total scale score range = 12–108

Duration of Training.

The mean number of days taken to complete the on-line tutorial was 27.04 (SD = 19.25, range 2–66). The mean total duration of training (on-line tutorial plus remote coaching) was 69.57 days (SD = 23.70, range 34–117).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop a multicomponent, technology-based platform with the potential to train large numbers of mental health professionals in BPT. Findings suggest that the training platform increased trainee’s knowledge of BPT concepts and principles as well as improved BPT skills. Moreover, trainees reported high levels satisfaction with the online tutorial content as well as with the live remote coaching. Overall, the findings of this preliminary study are encouraging and indicate high potential for the BPT technology training platform to meet a significant limitation in the field, namely limited access to engaging, efficient, and effective approaches to training mental health providers in BPT. The training platform initially provided an online tutorial which allowed for self-paced acquisition of material, interactive self-tests with feedback, and video case vignettes of skill implementation. Following the online tutorial, trainees were provided live, remote coaching via videoconference. The coaching provided the essential opportunity to learn how to use the BPT skills through modeling and role-playing with feedback—essential to skill acquisition (Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010). Evaluation of skill competencies is a critically overlooked aspect of continuing education programs. Use of web-based technologies can help facilitate this important aspect of training. Some have even suggested a competency-based system for awarding CE credits (Washburn et al, 2019).

Results of the study demonstrated that following the training, participants self-reported high levels of understanding and competence in the concepts, principles, and techniques of BPT. It is important to note that trainees had low levels of self-reported competence at pre-training with a relatively large standard deviation. It is likely that the large effects are driven by those trainees with initial low levels of initial competence. Importantly, self-reported increases in competence were paralleled by data demonstrating increases in observed skills. Specifically, on average, the number of steps of a BPT skill that was implemented correctly nearly doubled in all areas following training (Table 5). Similarly, observed ratings of the quality of each skill implemented increased considerably from pretraining to post-training (Table 6). These observations of improved quantity and quality of BPT skills implemented suggested that this brief technology-based platform changes behavior in substantial ways—effects size data for the observed rating were large across all outcomes.

Acceptability of a training approach is an important outcome, particularly when the training approach is to be disseminated to an audience with varying backgrounds (e.g., student-trainees versus licensed mental health providers; those with varying comfort with technology). As such, developing a user-friendly and highly acceptable training platform was a key goal of this study. Results of the study demonstrated that participants strongly agreed that the online tutorial was presented in a useful, relevant, and easy to understand manner. Moreover, participants rated that they were able to apply the skills, and overall were satisfied with the tutorial. The data strongly suggest that this platform serves as a strong foundation for learning BPT specifically and CBT approaches more generally.

The study had limitations that provide important context to better understand the findings and also point to future directions in this line of research and clinical training. First, this pilot study was an open trial with no control group or randomization to condition. This structure limits conclusions about causality as it does not control for external threats to validity, such as regression to the mean, maturation, or history (Sapp, 2017). Another limitation is that study participants did not adequately represent the full range of mental health practitioners in the field. As an example, social work professionals are centrally involved in the delivery of interventions for children and families; however, only one participant in this study had a social work background. Moreover, the modal primary theoretical orientation of study participants was behavioral/cognitive-behavioral—individuals who are likely motivated to acquire further training on interventions, as this one did, that align with their particular orientation. The sample was also homogenous with respect to gender, ethnicity, and years of experience, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to men, people of color, and more experienced clinicians. The online training was designed to cover fundamentals of social learning theory and BPT, which may be less useful for more advanced clinicians. However, the live supervision was conducted at the level of the trainee’s skill, and often focused on advanced topics, such as implementation and flexibility for particular presentations.

Beyond the representativeness of the sample, there were additional limitations. Most of the measures we used to assess outcomes were either adapted from other measures (e.g. the FIMP) or created by us. While they have high face validity, measures with documented strong psychometric properties would inspire more confidence in the results. In addition, we did not assess BPT skills in the context of naturalistic therapy sessions with a parent. As such, our data are proxies for skills implementation and fidelity. Lastly, we did not assess longer-term maintenance of BPT skills. Given that there is often a decrement in skills over time (Schoenwald, et al., 2011), the extent to which changes following training are maintained remains an unexplored issue.

Implications and Applications.

Despite the limitations of the study, the findings point to important clinical implications and future directions. First, findings suggest that the technology platform offers a user-friendly and effective approach to training both students and professionals in key, but limited, aspects of BPT. Importantly, relative to traditional, oft-used face-to-face training, the technology-focused training platform is efficient while remaining effective in teaching concepts and skills. To our knowledge, there are no other technology-based training approaches to BPT—a surprising state of affairs given the common presentation of disruptive behavioral problems in clinic settings and the prominence of BPT as a first-line treatment approach. Given our findings, a fully developed, technology-based training platform offers an opportunity to bridge the research-to-practice gap through significantly increasing the availability of BPT by increasing the number of professionals trained in this intervention. In particular, incorporating this technology-based platform may be especially useful as part of formal training opportunities (e.g., continuing education courses; coursework in graduate school).

While useful, this technology-based platform requires further development to maximize its potential. In this regard, future development and research efforts must focus on incorporating other common BPT skills (e.g., active ignoring), understanding whether the live remote coaching results in incremental effects over the web-based tutorial, considering how best to further support individuals who respond differently to initial training efforts (e.g., adaptive, ongoing training), considering what additional approaches may be needed to ensure maintenance of training effects over time, and ensuring translation of clinical skills from analogue to actual naturalistic practice contexts. As a case in point, the four BPT skills were chosen because they are the foundation for which subsequent skills are administered (e.g., praise is an essential skill that underlies other skills including shaping and planned attention). Future research examining whether there are particular skills that lend themselves to a hybrid or traditional face-to-face platform is a critical next step in order to move the field forward. Collectively, this study suggest that this technology-based platform offers a strong foundation for training, which has the potential for significantly advancing the dissemination of a highly effective intervention for a ubiquitous childhood mental health challenge.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement:

Findings from this pilot study suggest that an online course combined with live remote coaching is a promising way to increase the number of clinicians trained in evidence-based interventions for behavioral disorders in children.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grant number R43MH110279

CAMILO ORTIZ received his MS and PhD in clinical psychology from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is currently an associate professor of psychology and co-director of clinical training at Long Island University-Post. His areas of professional interest include behavioral parent training and disruptive behavior in children, pediatric elimination disorders, and cognitive–behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders.

HILARY B. VIDAIR received her PhD in combined clinical and school psychology from Hofstra University. She is currently the director of and associate professor in the clinical psychology doctoral program at Long Island University-Post. Her areas of research interest include behavioral parent training, managing parental depression and anxiety in the context of child treatment, engaging parents in therapy, and using innovative techniques to train clinicians in evidence-based treatments.

MARY ACRI received both her MSW in social work and her PhD in clinical social work from New York University. She is currently a senior research scientist at the McSilver Institute for Poverty, Policy and Research, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at New York University Langone. Her areas of professional interest include child disruptive behavior disorders; peer-delivered interventions, animal-assisted treatment for children with anxiety and autism and developing and testing unique models of detection and outreach for families impacted by poverty.

KENNETH KOBAK received his PhD in counseling psychology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He founded the Center for Telepsychology, conducting research on computer applications in psychology, including computerized assessments of adult and adolescent psychopathology, computer-administered psychotherapy, web-based clinical training and education, and use of mobile devices to enhance treatment compliance and treatment outcomes.

Footnotes

Dr. Kobak has a proprietary interest in the training tutorial described in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Camilo Ortiz, Long Island University-Post.

Hilary Vidair, Long Island University-Post.

Mary Acri, New York University.

Anil Chacko, New York University.

Kenneth Kobak, Center for Telepsychology.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Babinski LM, Hartsough CS, & Lambert NM (1999). Childhood conduct problems, hyperactivity-impulsivity, and inattention as predictors of adult criminal activity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 347–355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangor A, Kortum P, Miller J. (2009). Determining what individual SUS scores mean: Adding an adjective rating scale. Journal of Usability Studies, 4, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor A, Kortum P, & Miller JA (2008). The system usability scale (SUS): An empirical evaluation. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24, 574–594. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JE (2011). Utilizing technological innovations to enhance psychotherapy supervision, training, and outcomes. Psychotherapy, 48, 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan EM, Sellmaier C, Jivanjee P, & Grover L. (2018). Is online training an effective workforce development strategy for transition service providers? Results of a comparative study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 10.1177/1063426618819438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke J. (1996). SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale. In Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, & McClelland AL (Eds.), Usability evaluation in industry (pp. 189–194). London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Cartreine JA, Ahern DK, & Locke SE (2010). A roadmap to computer-based psychotherapy in the United States. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 18, 80–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Allan CC, Moody SS, Crawford TP, Nadler C, & Chimiklis A. (2017). Behavioral interventions. In Handbook of DSM-5 disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 617–636). Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- Galán Chardée A., Wang Frances L, Shaw Daniel S & Forbes Erika E (2019) Early childhood trajectories of conduct problems and hyperactivity/attention problems: Predicting adolescent and adult antisocial behavior and internalizing problems, Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1534206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, & Daleiden EL (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 566–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds JM, Beidas RS, & Kendall PC (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence–based practices: Training and consultation as implementation strategies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20, 152–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Duda MA, Naoom SF, & Van Dyke M. (2010). Implementation of evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Research findings and their implications for the future. In Weisz JR & Kazdin AE (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 435–450). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS (1994). Parenting through change: A training manual. Eugene: Oregon Social Learning Center. [Google Scholar]

- Granic I. & Patterson GR (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 13, 101–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood TM, Pratt D, Beutler LE, Bongar BM, Lenore S, & Forrester BT (2011). Technology, telehealth, treatment enhancement, and selection. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42, 448–454. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, & Davis AC (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 448–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, & Claussen AH (2017). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for disruptive behaviors in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46, 477–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, & Blase SL (2011). Rebooting psychotherapy research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 21–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna MS, & Kendall PC (2015). Bringing technology to training: Web-based therapist training to promote the development of competent cognitive-behavioral therapists. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 22, 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson NM, Forgatch MS, Rains LA, & Sigmarsdóttir M. (2009). Fidelity of implementation rating system (FIMP): The manual for PMTO™ (Revised ed.). Eugene, OR: Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Lipsitz JD, Markowitz JC, & Bleiberg KL (2017). Web-based therapist training in interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: Pilot study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 19, 306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Opler MG, & Engelhardt N. (2007). PANSS rater training using Internet and videoconference: Results from a pilot study. Schizophrenia Research, 92, 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Reynolds WM, & Greist JH (1994). Computerized and clinician assessment of depression and anxiety: Respondent evaluation and satisfaction. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Wolitzky-Taylor K, Craske MG, & Rose RD (2016). Therapist training on cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders using internet-based technologies. Cognitive Therapy and Research 41, 252–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, & Hinshaw SP (2004). Severity of adolescent delinquency among boys with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Predictions from early antisocial behavior and peer status. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, & Milne BJ (2002). Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: Follow-up at age 26 years. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 179–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordre M, Groholt B, Kjelsberg E, Sandstad B, & Myhre AM (2011). The impact of ADHD and conduct disorder in childhood on adult delinquency: A 30 years follow-up study using official crime records. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (1982). A social learning approach: Vol 3 Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Pidano AE, & Whitcomb JM (2012). Training to work with children and families: Results from a survey of psychologists and doctoral students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rivenbark JG, Odgers CL, Caspi A, Harrington H, Hogan S, Houts RM, ... & Moffitt TE. (2018). The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59, 703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp M. (2017). Primer on effect sizes, simple research designs, and confidence intervals. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Southam-Gerow MA, Chorpita BF, & Chapman JE (2011). Adherence measurement in treatments for disruptive behavior disorders: Pursuing clear vision through varied lenses. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18, 331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Biswas A, … Karch KM (2011). The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(1), 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen J, Albrecht G, Muris P, & de Ruiter C. (2017). Treatment fidelity during therapist initial training is related to subsequent effectiveness of Parent Management Training—Oregon Model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 1991–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn JJ, Lilienfeld SO, Rosen GM, et al. (2019). Reaffirming the scientific foundations of psychological practice: Recommendations of the Emory meeting on continuing education. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 50, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. (2005). Interactive multimedia-based e-learning: A study of effectiveness. The American Journal of Distance Education, 19, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.