Abstract

Through a rapid review drawing on pandemics and epidemics with associated school closures, this article aims to understand first, the state of the evidence on impacts of school closures on select child protection outcomes and second, how governments have responded to school closures to protect the most vulnerable children. Only 21 studies out of 6433 reviewed met the inclusion criteria, with most studies exploring the effects of Ebola. While few studies were identified on harmful practices, a more robust evidence base was identified in regards to adolescent pregnancy, with studies pointing to its increase due to the epidemic or infection control measures, including school closures. The evidence base for studies exploring the impact on violence outcomes was limited, with sexual violence and exploitation located in a few studies on Ebola. Important lessons from this exercise can be applied to the COVID-19 response, particularly the inclusion of the most vulnerable children in programming, policy and further research.

Keywords: Rapid review, School closures, Pandemics, Child protection

1. Introduction

As of December 2nd, at the time the authors were concluding this article, COVID-19 had claimed the lives of 1.4 million people around the globe and positive cases had surpassed 62 million (WHO, 2020). In tandem with the considerable loss of life, COVID-19 has led to an unprecedented closure of schools. While no concrete evidence is yet available on how the effects of the pandemic will play out - as we are still in the midst of it - the wide ranging impacts of school closures on children during this global crisis have begun to be assessed (Baron et al., 2020). Azevedo et al. (2020) estimated that the closure of schools could result in an average loss of 0.6 years of learning adjusted for quality. Szabo and Edwards (2020) have recently estimated that the impacts of COVID-19 could result in an increase of 1 million adolescent pregnancies in 2020 and 2.5 million girls at risk of child marriage over the next five years, reversing decades of progress on these fronts.1

In the face of COVID-19, there is a growing need to understand the key threats to children and adolescents’ protection and well-being, which are essential in developing effective interventions to mitigate such threats. Yet, much of the research being produced is not child- or adolescent-specific or fails to disaggregate the effects on children and adolescents. In addition, while we do not yet know to what extent school closures play a role in some of these negative outcomes, we do know that schools are not only places where children learn. In many contexts, schools are also a major source for children’s nutrition, for health services and a safe space for children who may face violence.2

Through a rapid review drawing on pandemics and epidemics with associated school closures, this article aims to understand the state of the evidence on their possible impacts on select child protection outcomes. The following research questions will guide this article:

-

•

What is the state of the evidence on the impacts of pandemics and epidemics with associated school closures on select child protection outcomes – including i) child labor; ii) early and adolescent pregnancy, iii) harmful practices such as child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), and iv) violence affecting children?

-

•

How have governments responded to school closures? What has been done during emergencies with school closures to protect children, including the most vulnerable, and to ensure their well-being? What are the lessons learned for the COVID-19 pandemic?

This article will be structured as follows: the second section will include a short description of concepts used throughout the article accompanied by a theoretical framework tracing the impacts of pandemics/epidemics-associated school closures on child protection outcomes. The third section will summarize the methodology used to address the research questions posed, particularly centering on the methods for the rapid review of evidence. Section four will center on the findings of the review, providing first a summary account of the results of the rapid review, followed by a specific focus on select child protection outcomes. The fifth section makes research and policy recommendations based on the findings of the review and is illustrated with information drawn from the UNICEF tracker of national education responses to COVID-19 that document how governments and UNICEF Country Offices have acted to protect children impacted by the current pandemic. The last section offers concluding thoughts.

2. Conceptual considerations and theoretical framework

2.1. Scope of this article

In order to answer the research questions, this article draws on a rapid review of the evidence on pandemics and epidemics and their impacts on child protection outcomes. The original review, published as a working paper by Bakrania et al. (2020) synthesizes evidence on the effects of pandemics and epidemics on child protection outcomes. Since child protection is complex and includes many areas that cut across multiple aspects of children’s lives, the original review had a very broad scope.3

In this article, we zero in on a portion of the evidence and report findings on the impacts of five pandemics and epidemics with associated school closures, on select child protection outcomes. In particular, this article centers on evidence from COVID-19, Ebola, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and H1N1/swine flu.4 The child protection outcomes selected are those that are largely covered in UNICEF’s protection work (UNICEF, 2020c), and those areas that we considered could be potentially affected by school closures, such as child labor, harmful practices – including FGM and child marriage - and violent discipline.

2.2. Conceptual considerations

Child protection refers “to prevention and response to violence, exploitation and abuse of children in all contexts. Reaching children who are vulnerable to these threats is another important component of child protection, such as those living without family care, on the streets, in detention or in situations of conflict or natural disasters” (UNICEF, 2020a). This article focuses on a selection of child protection issues, namely: child labor, harmful practices like child marriage and FGM, as well as violent discipline at home and sexual violence, including sexual exploitation. Because child marriage is often associated with adolescent pregnancy, both as a consequence as well and a determinant, the review also included studies that looked at the impacts of pandemics/epidemics with associated school closures on adolescent pregnancies.

For the purposes of this article, we have defined the child protection outcomes explored according to standard UNICEF definitions. Child labor is defined as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development (ILO, 2020). Early pregnancy is defined by UNICEF as pregnancy before the age of 15, while adolescent pregnancy occurs among those aged 15–19 (UNICEF, 2019). Child marriage refers to any formal marriage or informal union between a child under the age of 18 and an adult or another child (UNICEF, 2020b). FGM is any kind of procedure that involves partial or total removal of the female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons (UNICEF, 2020e).

Violent discipline includes forms of corporal punishment and psychological aggression, as well as use of guilt, humiliation, the withdrawal of love, or emotional manipulation to control children (UNICEF, 2011). Sexual violence “encompasses situations in which a child is forced to perform a sexual act or have unwanted sexual intercourse, is exposed to sexual comments or advances, impelled to engage in sex in exchange for cash, gifts or favors, coerced to expose her or his sexual body parts, subjected to viewing sexual activities or sexual body parts without his or her consent, or raped by a group of persons as part of a ritual, a form of punishment or the cruelty of war” (UNICEF, 2014).

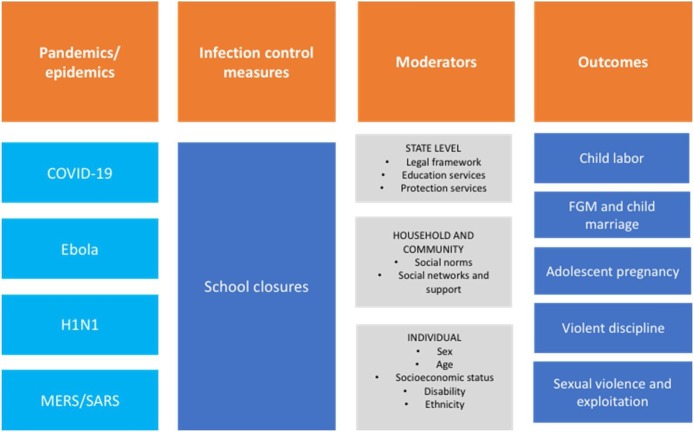

2.3. Pathway of pandemics/epidemics to short and long-term impacts on child protection outcomes

Fig. 1 shows a conceptual framework that illustrates the pathways of pandemics and epidemics and their impacts on child protection outcomes, resulting from the application of infection control measures, one of them being school closures. Child protection risks can stem directly from the pandemic or epidemic itself, or through related infection control measures. The moderators of child protection outcomes are separated into state, community and household, and individual child-level variables are interconnected, as illustrated in the socio-ecological model conceptualized originally by Bronfenbrenner (1979). This model posits that factors at different levels interact to explain a given outcome. In this particular case, moderators at the individual level, such as vulnerability status, sex or age can determine the level of access to services at the community and household level, which in turn affect the degree to which a child is protected (or left unprotected). The nature of the socio-ecological ordering of outcomes means that outcomes at the state, community and household, and individual child levels are nested; therefore, outcomes can have impacts through and across the different levels. Furthermore, the outcomes identified in the conceptual framework can materialize at different stages of the pandemic/epidemic, from the short-term, intermediate to long-term.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework on the relationship between pandemics/epidemics and child protection outcomes.

Source: Authors

3. Methodology and search results

This section of the article describes the methodology used to synthesize evidence in the initial rapid review and report back on the results (Bakrania et al., 2020). The review followed UNICEF’s methodological guidance on evidence synthesis, which describes a transparent, explicit and systematic approach to finding, collating and synthesizing evidence (Bakrania, 2020). Compared to a traditional systematic review, the approach was streamlined to make it ‘rapid’.

3.1. The process for synthesizing evidence ‘rapidly’

Systematic and targeted searches were conducted in a limited number of databases. This includes Web of Science and Google Scholar. We undertook further targeted and hand searches in specialist databases, including Social Systems Evidence, EPPI-Centre’s Living Map of the evidence on COVID-19, Save the Children’s Resource Centre, UNICEF’s Evidence Information System Initiative (EISI), the Better Care Network, Harvard University’s Centre on the Developing Child, the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action, Open Grey, and a COVID-19 public database of Chinese studies translated into English. Studies recommended by experts were also included and the references of key studies were screened as part of a backward snowballing process. No language restrictions were applied in the searches of academic databases but searches in grey literature sources were limited to English.

The screening and data extraction process were conducted simultaneously; and a quality appraisal of the included studies was not conducted (Bakrania et al., 2020). Screening was conducted by title and abstract, and then by full text according to a pre-defined inclusion criteria (see below).

3.2. Eligibility criteria

As mentioned, the rapid review had a broad scope. This article instead centers on a selection of outcomes described below, along with an indication of how the scope of the article differs from the broader scope of the rapid review. Infectious disease epidemics that became regional crises as well as global pandemics that had associated school closures as an infection control measure were included in our results for this article. A selection of child protection outcomes were considered. A detailed description of inclusion criteria used in the review is outlined below:

-

•

Population: Studies had to include children and adolescents (aged 10–19) as the main object of the study.

-

•

Pandemics / epidemics: For the purposes of this article, studies have been included if school closures were known to be an infection control measure in the contexts studied, even if not explicitly mentioned. Studies therefore had to refer to epidemics/pandemics with associated school closures −COVID-19, Ebola, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and/or H1N1.5

-

•

Child protection outcomes: Studies had to focus on the following child protection outcomes– child labor, harmful practices like child marriage and FGM, and adolescent pregnancy.6 Studies could also report on the following violence outcomes: violent discipline at home, sexual violence, and sexual exploitation.7

-

•

Context: Studies from both high- and low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) were considered.

-

•

Study types: Qualitative and quantitative primary empirical studies with any type of research design on the effects of the listed pandemics/epidemics were considered. Systematic or non-systematic reviews on the effects of pandemics/epidemics on child protection outcomes were also considered. Studies that were considered conceptual and/or theoretical were not included in the rapid review. Likewise, studies that did not report on their methodology were excluded from the review. Academic theses and dissertations, documentaries and other video material as well as entire books were also excluded from the review.

-

•

Time frame: Studies produced from 1980 onwards were considered in the review.

3.3. Results of the rapid review

A total of 6433 records resulting from searches, expert recommendations and snowballing were screened for the rapid review. Fifty-three studies met the inclusion criteria for the original review. Only five of these studies explicitly referred to the impacts of school closures as an infection control method. However, for the purposes of this article, a further 21 studies have been included. From this total of 26 studies, one is a systematic review focused on Ebola, while six non-systematic reviews were also centered on Ebola. Nineteen single studies focused on the Ebola outbreak and only one focused on COVID-19 and another on SARS. No relevant studies were identified on H1N1 or MERS. The most frequently studied region in single studies was West and Central Africa, and Sierra Leone and Liberia in particular, countries that were affected by Ebola. In regards to the impacts on child protection, 11 single studies on Ebola looked at the effects on adolescent pregnancy, five explored effects on child labor, and five explored the outcome of being orphaned. There were also a few single studies assessing the impacts of Ebola on inter-personal violence (IPV), sexual violence and violent discipline.

3.4. Limitations

The rapid review has a number of limitations, which also extend to this article. Firstly, there were very few studies that explicitly reported on the child protection impacts of school closures as an infection control measure. As a result, and in order to be able to draw upon a larger body of evidence, we included studies where school closures were known to be an infection control measure in the contexts reported on, even if not explicitly mentioned in the study. Secondly, the ‘rapid’ nature of the initial synthesis meant that a quality appraisal of studies was not possible. Another limitation of the review is that the studies included were all in English, meaning that there is evidence in other languages that we may have missed. A final limitation is that some of the recommendations highlighted in our final section are promising but not all have had rigorous evaluations.

4. Findings

The section below reports on the findings of the literature addressing the protection outcomes outlined in the inclusion criteria. Results of the rapid review are described for each of the outcomes and are disaggregated by age, gender and vulnerability (if evidence is available). Where specific evidence is identified on the direct impacts of school closures on the included outcomes, these are explicitly mentioned.

4.1. Impacts of health-related school closures on child labor

The rapid review found several studies reporting that, in health-related emergency settings, the reduction of household income and illness or death of breadwinners meant that children were increasingly engaged in wage labor in order to provide for their families (Bandiera et al., 2019; Elston et al., 2016). For instance, a study reported an assessment of children’s Ebola recovery in Sierra Leone which found that 43 % of 216 children reported having to work to support their families (Guo et al., 2012). In Liberia and Sierra Leone, a qualitative study documenting the consequences of Ebola on children and young people also found that children’s involvement in work had increased (Rothe, 2015). The evidence shows that, in pandemic and epidemic settings, children became increasingly engaged in different types of wage labor to generate income. In West Africa (Liberia and Sierra Leone), children affected by Ebola largely helped with business work or worked on farms (Rothe, 2015).

The studies reviewed did not make any explicit links between control measures, and specifically, school closures, and child labor. Yet, recent analysis using the UNICEF-supported MICS6 shows that children not in school are more likely to be working than those who are attending school with the poorest children most at risk (Park et al., 2020). In the current pandemic, UNICEF and ILO published a report warning that the number of children engaged in child labor globally may increase for the first time in 20 years (ILO and UNICEF, 2020). The report estimated that a 1 percentage point rise in poverty leads to at least a 0.7 percentage point increase in child labor (2020).

In relation to age, the evidence from the review showed that in Sierra Leone younger children were usually confined to helping with domestic chores, whilst older children would be involved in wage labor. With regard to gender, girls perceived that work had increased more for them than for boys. One study suggested that this may have been the case since girls were mainly engaged in activities such as petty trading of food which tended to continue also during the Ebola pandemic in West Africa (Rothe, 2015). The rapid review did not identify many studies specific to vulnerable children. A few studies mentioned that orphans often had to work to provide for their families as the main income earners to support their households. One study reported that in Sierra Leone children who had lost family members during the Ebola outbreak were taking on the role of the household’s wage earner (UNICEF, 2016).

4.2. Impacts of health-related school closures on early and adolescent pregnancy

The rapid review found an increase in adolescent pregnancies during, or in the aftermath of, a pandemic or epidemic (Denney et al., 2015; Elston et al., 2017; Kostelny et al., 2018; Menzel, 2019). Several studies spotlighted the linkage between school closures and teenage pregnancy during a health emergency. One study reported that in Sierra Leone there was a 25 % increase in adolescent pregnancy during the 2014 Ebola crisis in just one district (Elston et al., 2017). Another study using a quasi-experimental design exploring the impacts of a vocational programme on participant’s time use in Sierra Leone during the Ebola pandemic concluded that in high Ebola-related disruption villages where schools were closed and there was no access to the programme, younger girls faced large increases in exposure to time with men for sexual relations (Bandiera et al., 2019). The authors also found that moving from a low to a high Ebola disruption village was associated with 10.7 percentage point increase in the likelihood of becoming pregnant, a doubling from baseline (2019). Several studies also pointed out that without school attendance, many girls became pregnant, both with or without volition, experienced idleness, lack of hope in the future, and spent more time with men in their communities (Denney et al., 2015; Elston et al., 2017; Fraser, 2020; Kostelny et al., 2018; Peterman et al., 2020; Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015).

Additional control measures, such as social isolation, were associated with an increase in teenage pregnancies: social isolation exacerbated financial hardship, which in turn increased risks of sexual exploitation for girls and young women. In Sierra Leone, as poverty and food insecurity put increasing pressures on families and breadwinners, girls were found to engage in transactional sex to earn money, thus exposing themselves to a higher risk of becoming pregnant. Lockdown and quarantine were also identified as having a negative impact on the socio-economic conditions of families. Poverty also led to a reduction in the use of contraceptive methods by girls who had to prioritize food when spending their money (Kostelny et al., 2018; Menzel, 2019).

Regarding vulnerable children, the review found that teenage girls who lost their parents or caregivers were more likely to become pregnant, though evidence is limited (Denney et al., 2015). Indeed, orphaned girls in Sierra Leone were found to be more exposed to transactional sex, sexual abuse and exploitation, and thus unwanted pregnancies (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015; UN Women et al., 2014). Moreover, the review reported that often teenage girls who became pregnant dropped out of school even when the facilities eventually re-opened. A study of Sierra Leone highlighted the impact of teenage pregnancies on young fathers: boys who decided to assist a pregnant girl occasionally would have to drop out of school indefinitely to sustain their new families (Kostelny et al., 2018).

4.3. Impacts of health-related school closures on harmful practices - child marriage and FGM

The evidence shows that pandemics and epidemics have different effects on harmful practices: while the evidence points to an increase in child marriage, practices that involve FGM appear to decrease.

The majority of evidence showed that, due to infection control and containment measures, a number of West African countries witnessed an interruption of initiation practices, such as ‘bondo’, a traditional ceremony where FGM is practiced (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015; Rothe, 2015; UN Women et al., 2014). The government of Sierra Leone, for example, introduced a suspension of FGM practices during the Ebola crisis, as reported in two studies (Bandiera et al., 2019; UN Women et al., 2014). Though the moratorium of FGM practices constitutes a positive finding, one ethnography found that the lack of cultural and social activities led to other negative impacts as many girls declared feeling alone and detached from the rest of the community. Furthermore, the same studyfound that a large number of teenage girls in Sierra Leone were expected to undergo FGM once quarantine and lockdown were suspended (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015). Importantly, one study reported that girls and adolescents who had undergone practices involving FGM prior the Ebola outbreak and that were pregnant during the epidemic, were very likely to encounter fatal pregnancy outcomes and other health difficulties (O’Brien and Tolosa, 2016).

On the other hand, child marriage was found to be consistently on the rise in a large share of the reviewed literature. A few studies highlighted that in West Africa, the Ebola outbreakincreased instances of early marriage, a practice already present in the community (Fraser, 2020; Peterman et al., 2020; Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015). School dropout, teenage pregnancy and poverty were identified as pathways to child marriage (Fraser, 2020; Kostelny et al., 2018; Peterman et al., 2020; Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015).

Infection control measures, such as closure of schools and businesses, were found to have a negative impact on the socio-economic conditions of families, and early marriage was associated with increasing financial hardships during the Ebola outbreak (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015). When many young and teenage girls did not attend school during pandemics or epidemics, many of them would end up pregnant. These often unwanted pregnancies became major drivers of child marriage (Kostelny et al., 2018). The evidence also showed that child marriage is linked to other, subsequent practices affecting young girls including sexual exploitation and violence, marital rape, early pregnancy and IPV (Korkoyah and Wreh, 2015; Peterman et al., 2020).

4.4. Impacts of health-related school closures on violence against children

Records of increased IPV and sexual violence, including sexual exploitation, were found in Ebola-affected countries through surveys counting on self-reported data and addressing respondents’ perceptions (IRC, 2019; UN Women et al., 2014), and through studies combining qualitative methods with review of police and service provider records (Irish Aid and UNDP, 2015). This increase was implicitly or explicitly associated to infection control measures, including disruption of school and health services, which could be an effect of women’s increased exposure to violence-perpetrators at home, diminished access to health and protective services (Peterman et al., 2020), or to school which can serve as a protective space.

The evidence relating to violent discipline in the context of epidemics is very thin, and most studies identified were single qualitative and cross-sectional, and focused on the Ebola crisis. In Sierra Leone, most children respondents stated that the frequency of beatings at home had increased as compared to pre-Ebola levels, and for those children who didn’t declare an increase they acknowledged that pre-Ebola levels of abuse and violence were very high (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015). Furthermore, these children viewed school closures as a driving factor for this (Risso-Gill and Finnegan, 2015), which is consistent with the increased tensions in the home derived from quarantine and loss of income (Fraser, 2020).

In regards to evidence on vulnerable children, orphans, and teenage girls in particular, were found at an increased risk of IPV and sexual exploitation in Sierra Leone during the Ebola crisis (UN Women et al., 2014). It should be noted, however, that some studies reported a decrease in the incidence of IPV and sexual violence and exploitation (Bandiera et al., 2019; Korkoyah and Wreh, 2015) though the mechanisms by which this might occur were not dilucidated and findings rely on perceptions rather than objective measures. According to their perceptions survey, only 2.6 % of respondents believed violence levels had increased, and 65 % stated that they had decreased. Reporting may have also been challenged by inaccessibility to justice and medical services and by fear of infection (Irish Aid and UNDP, 2015).

5. Reflections for policy and further research in the COVID-19 era and beyond

This article attempted to tease out findings from a sub-set of evidence that focuses on pandemics and epidemics with associated school closures and their impacts on select child protection outcomes. The review of evidence has highlighted that there are many gaps in knowledge. Despite the limitations and caveats of the evidence – many of the studies included in the evidence review were not based on evaluative evidence of interventions - potential recommendations can be drawn, which are detailed in the section below. Related existing programmes and good practices from different countries are provided for illustrative purposes. The authors caution that the transferability of practices and programmes from one context to another requires adaptation to local contexts and circumstances. Furthermore, the scaling up of promising practices requires careful consideration of optimal scaling, as described in the work of McLean and Gargani (2019). This is followed by a list of general research guidelines to strengthen the evidence base and to better understand the impacts of health emergencies with school closures on protection outcomes.

5.1. Policy and programme recommendations

5.1.1. Place particular emphasis in policy responses on children in vulnerable circumstances, but particularly on girls and young women

Key approaches may include psychosocial interventions focused on improving mental health, social protection, cognitive interventions, and community-based interventions that provide families with resources and access to services.

| Ensuring pregnant adolescents have access to education |

|---|

| The importance of developing a targeted communication strategy was visible in the case of pregnant girls in Sierra Leone, who were banned by the Ministry of Education from attending schools when they were reopened after Ebola. Having learned from its experience during the outbreak (as well as an ECOWAS court decision ruling it discriminatory), Sierra Leone lifted its ban on pregnant girls in March 2020 and has promoted it as a measure that will help ensure girls’ education after the COVID-19 crisis. To ensure that pregnant girls would continue learning, UNICEF developed a ‘bridging programme’ allowing them to come to school after regular hours where they were able to follow the same curriculum offered to the other students. Following international support and advocacy, in São Tomé and Príncipe, a disciplinary act prohibiting pregnant girls in the third month of pregnancy from attending classes or school activities was also overturned this year (Ramos, 2020). |

5.1.2. Invest in social protection

The economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic could push up to 86 million more children into household poverty by the end of 2020, an increase of 15 per cent compared to 2019 (UNICEF, 2020d). There was some evidence that the negative impacts of previous pandemics/epidemics and now COVID-19 have been and are significantly higher for the poorest families. Financial support and social protection are key to enabling livelihoods during outbreaks and to counteracting adverse socio-economic and health-related shocks as families struggle to meet basic needs. Social safety nets could reduce the participation of children in paid and exploitative labor and decrease the chances of school dropout. This may further decrease the chances of early marriage and teenage pregnancy. Expanding social safety nets and providing support systems such as counseling or parenting programmes may also contribute positively to survivors of sexual violence and exploitation.

| Facilitating access to school for children from the poorest household |

|---|

| After Ebola, the Sierra Leone government waived school and examination fees for two years to motivate parents and communities to send all children back to school (Taulo, 2020). This was especially important because during the crisis many children were obliged to sell goods in informal markets, which resulted in an increase in child labor (2020). What is more, with the support of development partners, the government scaled-up school feeding programmes, as the poorest families had been unable to work during the Ebola quarantine and food security became a serious issue. In Cameroon, where all schools have been closed since mid-March 2020 because of COVID-19 (and briefly opened on June 1 st for those sitting in exams), non-formal education programmes have been allowed to continue to operate in the most vulnerable zones of the country, including urban pockets that have a higher rate of COVID-19 transmission as well as border areas with an inflow of refugees and conflict areas. |

5.1.3. Include considerations for children with disabilities in programmatic responses

Generally, the evidence on the effects of pandemics and epidemics on children with pre-existing conditions of vulnerability, such as children with disabilities is very limited. However, they are part of the population that is most at risk of being left out of programming, as children with disabilities currently constitute one third of children who are out of school globally (UNESCO, 2018).

| Back to school campaigns for children with disabilities |

|---|

| In Madagascar, the Inclusive Education Platform Committee organized a workshop on the specific needs of students with disabilities during COVID-19 school closures to strengthen the messaging to foster their reintegration in the next catch-up class campaign and to advocate for the continued sign-language translation of televised educational programming. Similarly, Kenya and Laos are organizing back-to-school campaigns to address the needs and concerns of children with disabilities. In Malaysia, UNICEF in collaboration with the National Early Childhood Intervention Council, provided online and teleservices to children and adolescents with disabilities, significantly increasing access to this support despite COVID-19 containment measures that have limited movement and in-person contact (UNICEF, 2020f). |

5.1.4. Promote access to health and protective services

The evidence from the Ebola outbreak in West Africa demonstrates that access restrictions to health services during the outbreak can lead to increases in sexual violence, IPV and adolescent pregnancy. This shows the importance of prioritizing services to respond to issues of violence against women and girls. This includes ensuring access to female healthcare workers and to safe, alternative and confidential spaces, as well as increasing communication and awareness of services through advocacy. Especially essential is the need to provide sexual and reproductive services for adolescents, as access to health services for this population group may not always be available or appropriate.

| Drawing on lessons from natural disasters and conflicts |

|---|

| Natural disasters constitute an opportunity to build upon systems to guarantee the protection and well-being of children, providing the impetus to develop or reactivate policies and approaches. In Indonesia and Sri Lanka, for example, the recovery phase after the 2004 tsunami paved the way for a strengthened child protection system: child protection issues were elevated on the national policy agenda and relevant human capacity and budgetary resources were improved (UNICEF, 2009). Basic steps taken to prevent exploitation were especially fruitful in the province of Aceh, which had the largest death toll in the country (2009). During the emergency phase, the police helped to protect children by patrolling exit points and crowded areas, such as airports and ports (2009). Subsequent interactions between child protection actors and the police created new entry points to strengthen the juvenile justice system, including the establishment of women’s and children’s police units in all districts (2009). Further examples can be taken from community led initiatives to continue children’s learning safely during conflict. In Colombia, where armed conflict has affected access to school, programmes such as La escuela busca al niño (the school finds the child) have been implemented to target those boys and girls most likely to be out of school due to armed conflict and displacement, providing them with catch up classes and supporting them to eventually enroll in formal schools (CODESOCIAL, 2009). In many cases, communities have devised alternative spaces and programmes to deliver learning safely for children. In 2006, when entire communities in conflict-affected areas in northern Central African Republic fled to avoid fighting and attacks targeting villages, communities established temporary “bush schools” (Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, 2020a). Parents, who were offered short teacher training courses, served as teachers and delivered lessons that attempted to parallel the national curriculum taught in government schools, teaching over 100,000 students under trees (Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, 2020b). Similarly, in northern Syria, temporary schools staffed by volunteer teachers were set up in more secure villages when parents in some areas had been afraid to send their children to their regular local schools (Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, 2020a). |

5.1.5. Support children’s psychosocial well-being and development when schools are closed and when cross sectoral services are closed with them

The evidence review identified stigmatization, discrimination and xenophobia as pervasive and widespread social phenomena accompanying pandemics and epidemics. These factors are often associated with long-term emotional and psychosocial outcomes. Based on the evidence from previous pandemics and epidemics, child protection responses to those affected by COVID-19 should include psychosocial interventions focused on improving children’s mental health. According to UNICEF’s Survey on the Socioeconomic Impact of the COVID-19 Response, 1.8 billion children live in the 104 countries where violence prevention and response services (such as household visits to children at risk of abuse, case management services or referral pathways and violence-related programs) have been disrupted due to the pandemic (UNICEF, 2020f). A main pillar of responses in countries affected by emergencies around the world has been the provision of psychosocial support, aimed at helping children overcome difficult experiences.

| Supporting victims of violence through online and phone-based psychosocial support |

|---|

| In 2015, South Africa developed reporting protocols as part of its National School Safety Framework, which is a guide for schools, districts and provinces ‘on a common approach to achieving a safe and healthy school environment’. This comprehensive framework comprises reporting protocols and clear guidelines on how to provide psychosocial support services for various cases, including violent crime such as physical assault, sexual assault/ rape; bullying/teasing and also in the case of property crime, robbery and carrying or possession of alcohol and other drugs (Makota and Leoschut, 2016). A child safeguarding policy has also been established by Vanuatu Ministry of Education and Training. The policy includes guidance on who can report, what and when to report, who to report to and possible outcomes, including the child’s medical, psychosocial and safety needs assessment (Vanuatu Ministry of Education and Training (MOET), 2017). To mitigate the cessation of some of the protection and support services offered through schools during COVID-19, such as protection against violence, mental health and psychosocial support programmes, online and phone initiatives have been used to support students. In Egypt and Bhutan, more than 300 children received remote psychosocial support during school closure through phone services and online platforms set up in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Given the increase in domestic violence in Mexico, the Ministry of Interior, the Secretariat for the Comprehensive Child Protection System, the Welfare Agency and UNICEF have partnered to train 911 operators on how to deal with calls regarding children, how to listen to them and where to refer them (UNICEF, 2020f). In addition, with support from Child Helpline International, four videos and four infographics were designed on psychological first aid, active listening and prompt detection of signs of violence at home (UNICEF, 2020c). Similarly, the existing Helpline 150 in Kazakhstan introduced a WhatsApp number to report violence against children along with a dissemination of cell phone contacts of child rights focal points in the regional authorities (2020c). |

5.2. Research recommendations

A few areas for potential research areas are listed below. These are not meant to be exhaustive, rather they provide options for practitioners seeking to prioritize research actions.

-

•

Focus on the impact of COVID-19 on drop-out, paying particular attention to the most vulnerable children and adolescents. For example, studies on the impact of the pandemic on the return to school for refugee girls and other marginalized groups will be critical, as a recent study has estimated that half of all girls in 10 countries for which there is enrollment data, will not return to school when classrooms re-open (Nyamweya, 2020).

-

•

Estimate the impacts of the pandemic on learning outcomes. At the outset of the pandemic, Azevedo et al. (2020) estimated that closures of schools for 5 months could result in a loss of learning of 0.6 years of schooling. Evidence has begun to build on the actual impacts on learning in high-income settings (see for example, Maldonado and De Witte, 2020); while evidence from LMIC settings is still largely pending.

-

•

Strengthen the evidence base on how non-formal programmes, particularly remedial and catch-up programmes can help learners in the aftermath of school closures.

-

•

Review the evidence on digital learning and its effectiveness in contributing to learning outcomes. The increased hype directed towards digital learning needs to be critically examined through an informed perspective that relies on existing evidence of its effectiveness.

Within these suggested areas, researchers may want to:

5.2.1. Focus on the most vulnerable children and adolescents

Very few of the studies included in the review made explicit reference to the most vulnerable children and adolescents, with most that did focusing largely on orphaned children. A particularly excluded group from the literature are children with disabilities and refugees. Given that the gaps between children with and children without disabilities have been growing (Male and Wodon, 2017) and gaps between refugee and host children exist in both access to education and learning outcomes (Piper et al., 2019; UNHCR, 2019; Uwezo, 2018), it is likely that school closures in previous pandemics/epidemics and currently during COVID-19 have exacerbated existing inequalities.

It is necessary to conduct further research of population heterogeneity, in order to determine associations between child protection and characteristics such as age, gender, disability, protection status and other forms of vulnerability. Developing strategies to target the most vulnerable children and adolescents is key. This is also relevant for high-risk groups, including the most vulnerable girls and young women, children in the poorest households as well as migrant and refugee children.

5.2.2. Build upon or reinforce the monitoring, evidence and learning functions of pre-existing programmes

Only one of the studies identified in the review had an experimental design. Pre-existing programmes present opportunities for conducting research with experimental, quasi-experimental designs or longitudinal studies to determine pre- and post-outbreak trends and impacts of a particular outbreak over time. If there is ongoing longitudinal data collection in areas when an outbreak hits, there is both baseline data and the infrastructure to quickly collect data. The use of administrative data and national statistics may also help to provide robust statistical evidence through econometric analysis of the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19.

5.2.3. Broaden geographic focus

As the rapid review showed, most of the evidence on pandemics/epidemics with associated school closures was on Ebola, which meant that studies were geographically limited. There is a need to expand the evidence base beyond Africa, and beyond Ebola-affected countries in particular. This may entail studies on previous or ongoing crises that are associated with school closures, such as natural disasters or armed conflict. This might yield useful findings due to the implementation of similar initiatives than those being used to reduce the negative effects of COVID-19.

5.2.4. Expand the evidence base on the impacts of control measures (especially school closures) beyond education, considering for example, the impacts on child protection outcomes

As reported in our review, very few studies directly mentioned the impacts of school closures on protection outcomes. In order to build a solid evidence base, it is necessary to conduct further research which centers on how infection control mechanisms – and school closures particularly - impact these outcomes. Researchers have already started to use the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to conduct quasi-experimental research: for example, Baron et al. (2020) have recently found that school teachers constitute an important source for child maltreatment allegations. The authors note that after school closures, child maltreatment reports dropped dramatically, indicating not that maltreatment has gone down but rather that there is a significant underreporting of cases in the state of the Florida and in the United States as a whole due to school closures, meaning that children very likely are “suffering in silence” (2020).

5.2.5. Make the risks and benefits of research on children immediately clear, and respect ethical principles

Not all of the evidence included in the rapid review made explicit reference to ethical protocols. UNICEF’s guidance on evidence generation involving children on the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that even if there are evidence gaps, conducting primary research should be carefully evaluated, especially if there is a risk of harm to the researcher and to participants. Face-to-face data collection should be clearly justified in terms of direct benefits and programming outcomes (Berman, 2020). Ethical protocols must be in place to ensure the ‘do no harm’ principle and methodologies must be appropriate for the issues and groups being addressed. For instance, remote data collection is likely to be inappropriate to conduct research on sensitive topics such as abuse and exploitation which are deeply traumatic. In the absence of appropriate data collection on sensitive topics, such as violence against children, Bhatia et al. (2020) pointed out to other existing data that could be helpful to guide programming and policy responses. For example, child helpline data, administrative data from emergency departments admission for injuries among minors or case data from case management system can help inform efforts to prevent and respond to violence, and do not require directly interviewing children.8

6. Conclusion

A review of the evidence found that most studies of pandemics/epidemics where school closures took place overwhelmingly explored the effects of Ebola and are therefore confined to West African countries affected by the outbreak. The three countries affected – Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea – all had school closures due to the pandemic but not all of the studies included in the review directly examined the effects of school closures. The child protection outcomes of interest explored were adolescent pregnancy, child labor, harmful practices such as FGM and child marriage, and violence against children. While few studies were located on harmful practices, a more robust evidence base was identified in regards to adolescent pregnancy, with studies pointing out an increase in the latter due to the epidemic or infection control measures, including school closures. The evidence base for studies exploring the impact on violence outcomes was limited, with sexual violence and exploitation located in a few studies on Ebola, while the evidence relating to violent discipline being very scarce. There are important lessons to be learned from this exercise and which can be applied to the COVID-19 response, particularly the inclusion of the most vulnerable children in programming, policy and particularly research, where the evidence base is still limited.

Author statement

Cirenia Chavez, Silvia Peirolo, Matilde Rocca, Alessandra Ipince: formal analysis, investigations, writing – original draft

Cirenia Chavez: Writing - review and editing

Shivit Bakrania: Conceptualization, methodology

Funding

This work was supported by UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions and feedback provided by Despina Karamperidou, Ramya Subrahmanian, Claudia Cappa and Matt Brossard.

Simulations have the limitation that they rely on a set of assumptions that may cause an underestimation of the impact of the pandemic on the outcomes explored; in this case learning loss and child marriage. For example, learning losses will depend on the extent to which mitigation is made available for students. Simulations assume that all governments are providing some form of remote learning using different varieties of platforms; however, these modalities might not be available to traditionally marginalized children such as children from ethnic minorities or those with disabilities (Szabo and Edwards, 2020).

This statement does not deny that schools and the spaces that surround them can also constitute environments where children are exposed to different forms of violence, such as bullying by peers or corporal punishment by teachers.

Bakrania, S., Chavez, C., Ipince, A., Rocca, M., Oliver, S., Stansfield, C., & Subrahmanian, R. (2020). Impacts of Pandemics and Epidemics on Child Protection: Lessons learned from a rapid review in the context of COVID-19, Innocenti Working Paper 2020−05. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

The initial review cited included a large number of studies on the impacts of HIV/AIDs, but these findings have been omitted from this article, as this global epidemic is not generally associated with school closures as an infection control measure

However, it is important to pay careful consideration to data privacy, data protection, and to anonymizing case records when using case data.

The original review also included evidence for HIV/AIDS and Zika, but we excluded these from the article as they did not have associated school closures.

The original review also reported on additional outcomes, including stigmatization, family separation and abandonment; and unsafe and irregular migration.

The original review also reported on additional violence outcomes, including intimate partner violence between married, cohabiting or dating partners; sexual violence and exploitation by caregivers and strangers; violent child discipline; child abuse and maltreatment; peer bullying; self-directed violence including suicide or self-harm; violence from security actors; gang involvement and crime; homicide; and online abuse and exploitation.

References

- Azevedo J., Hassan A., Goldemberger D., Iqbal S., Geven K. World Bank; 2020. Simulating the Potential Impacts of Covid-19 School Closures and Learning Outcomes.http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/798061592482682799/covid-and-education-June17-r6.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bakrania S. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti; 2020. Methodological Briefs on Evidence Synthesis Brief 1: Overview.https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/IRB%202020-01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bakrania S., Chavez C., Ipince A., Rocca M., Oliver S., Stansfield C., Subrahmanian R. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti; 2020. Pandemics, Epidemics and Child Protection Outcomes: a Rapid Review. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera O., Buehren N., Goldstein M.P., Rasul I., Smurra A. The World Bank; 2019. The Economic Lives of Young Women in the Time of Ebola: Lessons from an Empowerment Program. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baron E.J., Goldstein E.G., Wallace C.T. Suffering in silence: how COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3601399) Social Sci. Res. Network. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3601399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman G. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti; 2020. Ethical Consideration for Evidence Generation Involving Children on the COVID-19 Pandemic (Discussion Paper 2020-01)https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/DP%202020-01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia A., Peterman A., Guedes A. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti; 2020. Remote Data Collection on Violence against Children during COVID-19: a Conversation with Experts on Research Priorities, Measurement and Ethics.https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/2004-collecting-remote-data-on-violence-against-children-during-covid-19-a-conversation.html [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Harvard University Press; 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- CODESOCIAL . 2009. La Escuela Busca Al niño-a.https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Colombia_2009-003_-_Informe_final_UNICEF_ajustes(Septiembre).pdf [Google Scholar]

- Denney L., Gordon R., Ibrahim A. Overseas Development Institute; London: 2015. Teenage Pregnancy After Ebola in Sierra Leone.’. [Google Scholar]

- Elston J.W.T., Moosa A.J., Moses F., Walker G., Dotta N., Waldman R.J., Wright J. Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. J. Public Health. 2016;38(4):673–678. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston J.W.T., Cartwright C., Ndumbi P., Wright J. The health impact of the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak. Public Health. 2017;143:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E. VAWG Helpdesk; 2020. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Violence against Women and Girls; p. 16.https://bettercarenetwork.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/vawg-helpdesk-284-covid-19-and-vawg.pdf Helpdesk Research Report No. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack . 2020. Implementation – Safe Schools Declaration.https://ssd.protectingeducation.org/implementation/ [Google Scholar]

- Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack . 2020. Seek to Ensure the Continuation of Education During Armed Conflict – Safe Schools Declaration.https://ssd.protectingeducation.org/implementation/seek-to-ensure-the-continuation-of-education-during-armed-conflict/ [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Li X., Sherr L. The impact of HIV/AIDS on children’s educational outcome: a critical review of global literature. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):993–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILO . 2020. ILO Research Guides: Child Labour.https://libguides.ilo.org/child-labour-en/home [Google Scholar]

- ILO, UNICEF . 2020. COVID-19 and Child Labour: a Time of Crisis, a Time to Act.https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid-19-and-child-labour-a-time-of-crisis-a-time-to-act/ [Google Scholar]

- IRC . International Rescue Committee; 2019. Everything on Her Shoulders.https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/3593/genderandgbvfindingsduringevdresponseindrc-final8march2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Irish Aid, UNDP . UNDP; 2015. Assessing Sexual and Gender Based Violence during the Ebola Crisis in Sierra Leone.https://www.sl.undp.org/content/sierraleone/en/home/library/crisis_prevention_and_recovery/assessing-sexual-and-gender-based-violence-during-the-ebola-cris.html [Google Scholar]

- Korkoyah D., Wreh F. UN Women, Oxfam; 2015. Ebola Impact Revealed: an Assessment of the Differing Impact of the Outbreak on Women and Men in Liberia.https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/rr-ebola-impact-women-men-liberia-010715-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kostelny K., Lamin D., Manyeh M., Ondoro K., Stark L., Lilley S., Wessells M. 2018. Worse Than the War. Save the Children.https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/worse-war-ethnographic-study-impact-ebola-crisis-life-sex-teenage-pregnancy-and-community [Google Scholar]

- Makota G., Leoschut L. The National School Safety Framework: a framework for preventing violence in South African schools. Afr. Saf. Promot. A J. Inj. Violence Prev. 2016;14(2):18–23. doi: 10.4314/asp.v14i2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado J.E., De Witte K. Ku Leuven Department of Economics; 2020. The Effect of School Closures on Standardised Student Test Outcomes.https://feb.kuleuven.be/research/economics/ces/documents/DPS/2020/dps2017.pdf Discussion Paper Series DPS 20.17. [Google Scholar]

- Male C., Wodon Q.T. World Bank; 2017. Disability Gaps in Educational Attainment and Literacy [Text/HTML]https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail [Google Scholar]

- McLean R., Gargani J. Routledge; 2019. Scaling Impact: Innovation for the Public Good. [Google Scholar]

- Menzel A. ‘Without education you can never become president’: teenage pregnancy and pseudo-empowerment in Post-Ebola Sierra Leone. J. Interv. Statebuilding. 2019;13(4):440–458. doi: 10.1080/17502977.2019.1612992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamweya N. 2020. Displacement, Girls’ Education and COVID-19. Education for All.https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/displacement-girls-education-and-covid-19 June 26. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M., Tolosa X. The effect of the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus disease epidemic on multi-level violence against women. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2016:9. doi: 10.1108/IJHRH-09-2015-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Mizunoya S., Cappa C., Cardoso M., De Hoop J. UNICEF Connect; 2020. Digging Deeper With Data: Child Labour and Learning.https://blogs.unicef.org/evidence-for-action/digging-deeper-with-data-child-labour-and-learning/ [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A., Potts A., O’Donnell M., Thompson K., Shah N., Oertelet-Trigione S., van Gelder N. Centre for Global Development; 2020. Pandemics and Violence against Women and Children.https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/pandemics-and-violence-against-women-and-girls.pdf CGD Working Paper No. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Piper B., Dryden-Peterson S., Chopra V., Reddick C., Oyanga A. Are refugee children learning? Early grade literacy in a refugee camp in Kenya. J. Educ. Emergencies. 2019;5(2):71–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos L. GPE’s COVID-19 Response; 2020. Keeping Pregnant Girls in School in Sao Tome and Principe.https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/keeping-pregnant-girls-school-sao-tome-and-principe [Google Scholar]

- Risso-Gill I., Finnegan L. Save the Children; 2015. Children’s Ebola Recovery Assessment: Sierra Leone; p. 36.https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/global/reports/emergency-humanitarian-response/ebola-rec-sierraleone.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rothe D. Plan International; 2015. Ebola: Beyond the Health Emergency: Summary of Research into the Consequences of the Ebola Outbreak for Children and Communities in Liberia and Sierra Leone.https://www.plan.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/GLO-Ebola-Final-IO-Eng-Feb15.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G., Edwards J. Save the Children; 2020. The Global Girlhood Report 2020: How COVID-19 Is Putting Progress in Peril.https://s3.savethechildren.it/public/files/uploads/pubblicazioni/global-girlhood-report-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Taulo W. UNICEF Connect; 2020. Lessons From Ebola: How to Reach the Poorest Children When Schools Reopen—UNICEF Connect.https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/lessons-from-ebola-how-to-reach-the-poorest-children-when-schools-reopen/ [Google Scholar]

- UN Women, Oxfam, Statistics Sierra Leone . Ministry of Social Welfare, Gender and Children’s Affairs Sierra Leone; 2014. Report of the Multisector Impact Assessment of Gender Dimensions of the Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in Sierra Leone.https://awdf.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-REPORT-OF-THE-Multi-Sectoral-GENDER-Impact-Assessment_Launchedon_24th-Feb-2015_Family_kingdom_Resort.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO . 2018. First Release of Results: Third Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study.http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002442/244239e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR . UNHCR; 2019. Stepping up: Refugee Education in Crisis.https://www.unhcr.org/steppingup/ [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; Sri Lanka and Maldives: 2009. Children and the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: Evaluation of UNICEF’s Response in Indonesia; pp. 2005–2008.https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Children_and_the_2004_Indian_Ocean_tsunami_Indonesia-Sri_Lanka-Maldives.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; 2011. Child Disciplinary Practices at Home: Evidence from a Range of Low- and Middle-income Countries.https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-disciplinary-practices-at-home-evidence-from-a-range-of-low-and-middle-income-countries/ [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2014. Hidden in Plain Sight: a Statistical Analysis of Violence Against Children.https://www.unicef.org/publications/index_74865.html [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; 2016. Care and Protection of Children in the West African Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic: Lessons Learned for Future Public Health Emergencies.https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/separated-children-in-an-emergency/care-and-protection-of-children-in-the-west-african-ebola-virus-disease-epidemic-lessons-learned-for [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF DATA; 2019. Early Childbearing.https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/adolescent-health/ [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; 2020. A Generation to Protect: Monitoring Violence, Exploitation and Abuse of Children Within the SDG Framework.https://data.unicef.org/resources/a-generation-to-protect/ [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF Data. UNICEF DATA; 2020. Child Marriage.https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/ [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. Child Protection.https://www.unicef.org/protection [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. COVID-19: Number of Children Living in Household Poverty to Soar by up to 86 Million by End of Year.https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/covid-19-number-children-living-household-poverty-soar-86-million-end-year [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . 2020. Female Genital Mutilation.https://www.unicef.org/protection/female-genital-mutilation [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; 2020. Protecting Children from Violence in the Time of COVID-19: Disruptions in Prevention and Response Services.https://www.unicef.org/media/74146/file/Protecting-children-from-violence-in-the-time-of-covid-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Uwezo . 2018. Are Our Children Learning? Uwezo Learning Assessment in Refugee Contexts in Uganda.https://www.twaweza.org/go/uwezo-learning-assessment-in-refugee-contexts-in-uganda [Google Scholar]

- Vanuatu Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) MOET; 2017. Child Safeguarding Policy.https://moet.gov.vu/docs/policies/Child%20Safeguarding%20Policy%202017_2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int [Google Scholar]