Abstract

Objectives

In recent years, several instruments for measuring patient safety culture (PSC) have been developed and implemented. Correct interpretation of survey findings is crucial for understanding PSC locally, for comparisons across settings or time, as well as for planning effective interventions. We aimed to evaluate the influence of gender, profession, and managerial function on perceptions of PSC and on the interplay between various dimensions and perceptions of PSC.

Methods

We used German and Swiss survey data of frontline physicians and nurses (n = 1786). Data analysis was performed for the two samples separately using multivariate analysis of variance, comparisons of adjusted means, and series of multiple regressions.

Results

Participants’ profession and managerial function had significant direct effect on perceptions of PSC. Although there was no significant direct effect of gender for most of the PSC dimensions, it had an indirect effect on PSC dimensions through statistically significant direct effects on profession and managerial function. We identified similarities and differences across participant groups concerning the impact of various PSC dimensions on Overall Perception of Patient Safety. Staffing and Organizational Learning had positive influence in most groups without managerial function, whereas Teamwork Within Unit, Feedback & Communication About Error, and Communication Openness had no significant effect. For female participants without managerial functions, Management Support for Patient Safety had a significant positive effect.

Conclusions

Participant characteristics have significant effects on perceptions of PSC and thus should be accounted for in reporting, interpreting, and comparing results from different samples.

Key Words: patient safety culture, gender, profession, healthcare, patient safety

Internationally, healthcare organizations increasingly strive to develop and support patient safety culture (PSC).1 Therefore, reliable instruments to measure PSC are needed. Only then can results accurately describe the state of PSC and be compared across different healthcare settings or used to evaluate changes in PSC over time. Various PSC instruments have been developed and validated worldwide. These instruments typically consist of questionnaires, designed to capture the perceptions of frontline clinicians, mainly physicians and nurses.2–4 The results of these surveys inform hospital management regarding various aspects of PSC, such as teamwork or communication, point to problematic areas, and drive targeted interventions.

Studies from various countries have shown that staff perceptions may vary significantly by different participant characteristics, such as gender,5,6 profession,7,8 and managerial function.8–12 Although the concept of safety culture is considered to be shared among team/organization members,13 staff perceive different aspects of shared culture from the viewpoint of their individual characteristics and team roles. A recent meta-analysis found that the proportion of physicians in the study sample was significantly associated with outcomes in various PSC dimensions.7 To interpret the results of PSC studies properly, it is extremely important to understand and quantify the effect of participant characteristics on staff perceptions of PSC.

The ultimate goal behind conducting PSC surveys is to measure and gradually improve overall patient safety. To strategically plan interventions, it is important to understand not only how team members perceive different aspects of PSC but also how these aspects contribute to an understanding of the general state of patient safety. There is some evidence that different characteristics of team members may also influence how perception of the overall state of patient safety is formed. For example, Richter et al.10 demonstrated that for managerial staff and frontline workers, different dimensions of PSC determined the perceived frequency of events reported.10 A better understanding of these variations can inform decision-makers to plan effective interventions targeted to specific employee groups, to improve safety culture and, eventually, patient safety in general.

In this study, we set out to investigate (1) the influence of participant characteristics of gender, profession, and managerial function on clinicians’ perceptions of PSC and (2) the effect of these characteristics on the relationships between different aspects of PSC and clinicians’ perceptions of patient safety.

METHODS

Setting

We used data from two survey studies. The first collected data between April and July 2015 in two German university hospitals. The second study occurred in June and July 2017 in one Swiss university hospital. Both studies were approved by relevant ethics committees (#350/14, #547/2014BO1, #160/17).

Sample

For the analysis, we used the samples from both studies. Because frontline physicians and nurses are the largest staff categories and also the staff categories included most frequently in PSC studies, we selected physicians and nurses who indicated having daily contact with patients. We excluded all cases with missing answers on any of our key variables: gender, profession, and managerial function.

Measure

One of the most frequently used instruments for studying PSC in the hospital setting is the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSPSC).14 It has been translated, adapted, and validated in many languages and used around the globe3 including Germany15 and Switzerland.16

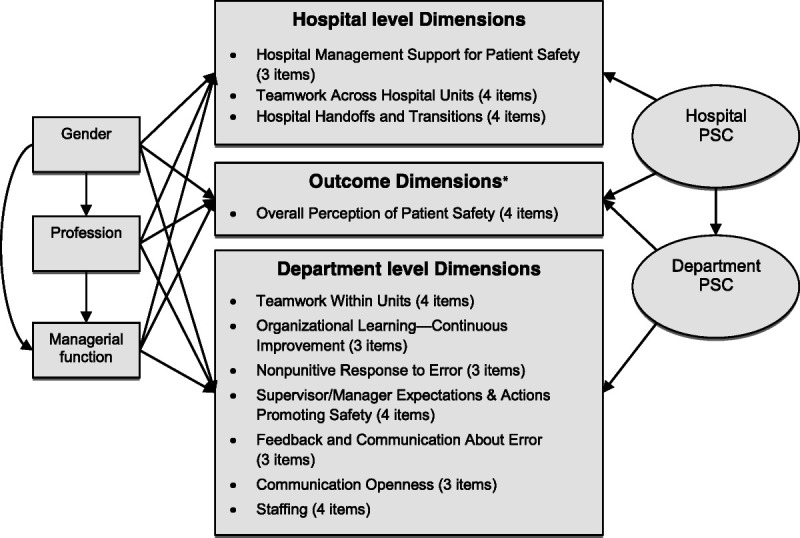

The items of the HSPSC elicit employees’ perceptions on various aspects of PSC using five-point Likert scale. The 42 individual items of the instrument form 12 dimensions of PSC. Figure 1 presents the model used in our analysis. It comprises 11 dimensions of PSC: three hospital level dimensions, seven department level dimensions, and an outcome dimension Overall Perception of Patient Safety. The outcome dimension, Frequency of Error Reporting, was not part of our research question and thus not included in the model. The three hospital level dimensions are Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety, Teamwork Across Hospital Units, and Hospital Handoffs & Transitions. The seven dimensions on the department level are Teamwork Within Units, Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement, Nonpunitive Response to Error, Supervisor Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety, Feedback & Communication About Error, Communication Openness, and Staffing.14

FIGURE 1.

Model used in the analysis. Research model based on the original structure of the HSPSC.14 Individual items of the questionnaire are grouped in PSC dimensions. We expanded the model by adding the latent constructs Hospital PSC and Department PSC, as well as the effects of participants’ gender, profession, and managerial function. *The HSPSC includes one more outcome dimension, Frequency of Error Reporting, which was not part of our research question so was not included in the model.

In both studies, we also collected demographic information, such as participants’ department, gender, profession, direct patient contact, and managerial function.

Statistical Analysis

Data Processing

Before analysis, negatively coded items were reversed. To maintain high data quality, we removed participants with more than 30% missing answers on PSC items. Remaining missing values were imputed separately for each study sample using multiple imputation with expectation maximization algorithm.17,18 We calculated mean scores for the 11 PSC dimensions by averaging the corresponding items.

Data Analysis

To evaluate the effects of gender, profession, and managerial function and their interactions on different aspects of PSC, we conducted 11 unbalanced factorial analyses of variance (ANOVAs), one for each PSC dimension in our model.19 We used ω2 to estimate the effect size. To analyze the overall effect of the three participant characteristics on the correlated system of the 11 PSC dimensions, we used multivariate ANOVA.19 To account for nested data, we included department as a control variable. Using the three variables gender (female/male), profession (nurse/physician) and managerial function (yes/no) resulted in eight groups for comparison. To explore the respective group differences, we used least squares means (LS means) post hoc test with Tukey-Kramer adjustment accounting for unbalanced groups.19

Direct effects analyzed in our model are visualized in Figure 1. In addition, we considered an indirect effect of gender through profession and managerial function, as well as an indirect effect of profession through managerial function. To reflect the fact that the PSC dimensions refer to different organizational levels, we included Hospital PSC and Department PSC as latent constructs. We used confirmatory factor analysis to test model fit in both samples. The following indices with corresponding cutoff values were considered: standardized root mean residual (SRMR) < 0.08, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) > 0.90, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, and normed fit index (NFI) > 0.95.18

To evaluate how participant characteristics affect the relationship between different aspects of PSC and participants’ perceptions of patient safety, we used multiple linear regressions with the outcome dimension Overall Perception of Patient Safety as a dependent variable, and 10 dimensions of PSC as independent variables. We conducted separate analyses for the eight groups of participants (gender × profession × managerial function). We used confidence intervals of the estimated parameters to compare them across different groups. Conducting all analyses separately for the German and Swiss samples allowed for exploring similarities and differences between these two countries. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4.

RESULTS

Study Samples and Descriptive Statistics

Response rate was 39.6% and 33.4%, respectively. The complete data set consisted of 1943 physicians and nurses with regular patient contact. We excluded 135 cases because of missing answers on gender and managerial function, and another 22 cases with more than 30% missing answers on PSC items. A combined sample of 1786 physicians and nurses from two countries was used for analysis.

The two samples were of comparable size (nA = 896 and nB = 890). In both samples, there were more females than males, more nurses than physicians, and more participants without managerial function. Most participants in both samples reported more than 5 years of professional experience. Table 1 presents comparable characteristics of the two samples.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Two Samples

| Sample A | Sample B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nA | % | nB | % | |

| Total participants | 896 | 100.0 | 890 | 100.0 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 612 | 68.30 | 665 | 74.72 |

| Male | 284 | 31.70 | 225 | 25.28 |

| Profession | ||||

| Nurse | 542 | 60.49 | 691 | 77.64 |

| Physician | 354 | 39.51 | 199 | 22.36 |

| Managerial function | ||||

| No | 709 | 79.13 | 628 | 70.56 |

| Yes | 187 | 20.87 | 262 | 29.44 |

| Years in department | ||||

| <1 | 54 | 6.03 | 135 | 15.17 |

| 1–5 | 296 | 33.04 | 335 | 37.64 |

| >5 | 432 | 48.21 | 409 | 45.96 |

| Missing | 114 | 12.72 | 11 | 1.24 |

| Years in profession | ||||

| <1 | 22 | 2.46 | 32 | 3.60 |

| 1–5 | 192 | 21.43 | 199 | 22.36 |

| >5 | 662 | 73.88 | 655 | 73.60 |

| Missing | 20 | 2.23 | 4 | 0.45 |

Effects of Participant Characteristics on Perceptions of PSC

The main effects of profession and managerial function, along with the direction of statistically significant differences, based on the results of the post hoc tests comparing the LS means for effects of participant characteristics in the two samples, are presented in Table 2. Gender was omitted from Table 2 because it had no significant effect. In addition, apart from the interaction effect of managerial function × gender in sample B (P = 0.01, ω2 = 0.006), none of the interaction effects were significant.

TABLE 2.

Comparisons Based on LS Means and Main Effects (ω2) Based on Unbalanced Factorial Three-Way ANOVAs for Managerial Function and Profession Across the Two Study Samples

| Profession* | Managerial Function* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample A | Sample B | |

| Outcome | ||||

| Overall Perception of Patient Safety |

Nurse < physician P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.017 |

Nurse < physician P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.016 |

No < yes P = 0.004, ω2 = 0.007 |

No effect P = 0.32 |

| Hospital PSC | ||||

| Management Support for Patient Safety |

Nurse < physician P = 0.001, ω2 = 0.009 |

No effect P = 0.07 |

No < yes P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.019 |

No effect P = 0.18 |

| Teamwork Across Units |

Nurse < physician P = 0.003, ω2 = 0.008 |

Nurse < physician P = 0.001, ω2 = 0.011 |

No < yes P = 0.001, ω2 = 0.009 |

No effect P = 0.063 |

| Handoffs & Transitions |

Physician < nurse P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.023 |

Physician < nurse P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.019 |

No effect P = 0.38 |

No effect P = 0.17 |

| Department PSC | ||||

| Teamwork Within Units | No effect P = 0.97 |

No effect P = 0.48 |

No < yes P = 0.023, ω2 = 0.004 |

No < yes P = 0.013 ω2 = 0.006 |

| Organizational Learning— Continuous Improvement |

No effect P = 0.19 |

No effect P = 0.94 |

No < yes P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.030 |

No < yes P = 0.028, ω2 = 0.004 |

| Nonpunitive Response to Error | No effect P = 0.15 |

No effect P = 0.92 |

No < yes P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.020 |

No < yes P = 0.001, ω2 = 0.010 |

| Supervisor Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety | No effect P = 0.41 |

No effect P = 0.41 |

No < yes P = 0.009, ω2 = 0.006 |

No < yes P = 0.012, ω2 = 0.006 |

| Feedback & Communication About Error | No effect P = 0.61 |

No effect P = 0.07 |

No < yes P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.028 |

No < yes P = 0.012, ω2 = 0.005 |

| Communication Openness† |

Physician < nurse P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.016 |

Physician < nurse P = 0.002, ω2 = 0.010 |

No < yes P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.019 |

No effect P = 0.36 |

| Staffing |

Nurse < physician P < 0.0001, ω2 = 0.013 |

No effect P = 0.57 |

No < yes P = 0.011, ω2 = 0.005 |

No effect P = 0.80 |

Main effect and group difference for gender were not significant for any of the PSC dimensions. All interaction effects except one were not significant in both samples.

*Effects with P < 0.05 are presented in bold.

†Significant interaction effect of managerial function × gender in sample B (P = 0.01, ω2 = 0.006).

Respondents with managerial function reported more positive perceptions in 10 of the 11 PSC dimensions in sample A (all dimensions except Hospital Handoffs & Transitions) and in five of seven department level dimensions in sample B. In both samples, nurses’ perceptions were more positive compared with those of physicians for dimensions Handoffs & Transitions and Communication Openness and less positive for Overall Perception of Patient Safety and Teamwork Across Hospital Units. In addition in sample A, nurses’ perceptions were less positive for the dimensions Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety and Staffing. Overall, we identified more statistically significant differences in sample A, compared with sample B.

The overall effect of the three participant characteristics gender, profession, and managerial function on the correlated system of PSC dimensions (multivariate ANOVA including department as a control) was statistically significant for profession and managerial function (P < 0.001 in both samples for both variables). The overall effect of gender, as well as that of all interactions between the three participant characteristics, was not statistically significant.

The research model established in Figure 1 had acceptable model fit for the data from the two samples (sample A: SRMR = 0.05, GFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.88, NFI = 0.87; sample B: SRMR = 0.04, GFI = 0.95, CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.92).

Direct and indirect effects of the three participant characteristics were analyzed using path analysis based on our research model (Fig. 1). Similar to the ANOVA results, managerial function had statistically significant direct effects on 10 of 11 PSC dimensions (all except Hospital Handoffs and Transitions) in sample A and on five of seven department level dimensions in sample B. All these effects were positive, meaning that participants with managerial functions reported more positive perceptions. Profession had statistically significant direct effects on eight and five PSC dimensions in two samples, respectively. A significant direct effect of gender was found for only two dimensions in sample A: Feedback & Communication About Error and Staffing. In our model, we also evaluated the indirect effects of gender on PSC dimensions through profession and managerial function, as well as the indirect effect of profession through managerial function. Indirect effects of gender and profession are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Standardized Direct and Indirect Effects of the 3 Participant Characteristics Based on Path Analysis

| Standardized Direct Effect | Standardized Indirect Effect | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Profession | Managerial Function* | Gender | Profession | |||||||

| Sample A | Sample B | Sample A | Sample B | Sample A | Sample B | Sample A | Sample B | Sample A | Sample B | ||

| Profession | St. effect 95% CI P |

0.42 0.36 to 0.47 P < 0.0001 |

0.4 0.34 to 0.45 P < 0.0001 |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Managerial Function Outcome |

St. effect 95% CI P |

0.18 0.11 to 0.25 P < 0.0001 |

0.11 0.05 to 0.18 P = 0.001 |

0.17 0.1 to 0.24 P < 0.0001 |

0.25 0.19 to 0.32 P < 0.0001 |

NA | NA | 0.07 0.04 to 0.1 P < 0.0001 |

0.1 0.07 to 0.13 P < 0.0001 |

NA | NA |

| Overall Perception of Patient Safety | St. effect 95% CI P |

0.05 −0.02 to 0.12 P = 0.17 |

0.04 −0.03 to 0.11 P = 0.23 |

0.20 0.13 to 0.27 P < 0.0001 |

0.15 0.08 to 0.22 P < 0.0001 |

0.13 0.06 to 0.19 P < 0.001 |

0.03 −0.04 to 0.1 P = 0.41 |

0.12 0.08 to 0.15 P < 0.0001 |

0.07 0.04 to 0.1 P < 0.0001 |

0.02 0.01 to 0.04 P = 0.002 |

0.01 −0.01 to 0.02 P = 0.42 |

| Hospital PSC | |||||||||||

| Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.05 −0.12 to 0.02 P = 0.21 |

−0.01 −0.08 to 0.06 P = 0.79 |

0.17 0.10 to 0.24 P < 0.0001 |

0.06 −0.01 to 0.14 P = 0.09 |

0.19 0.13 to 0.26 P < 0.0001 |

0.02 −0.05 to 0.09 P = 0.50 |

0.12 0.08 to 0.15 P < 0.0001 |

0.03 0 to 0.06 P = 0.05 |

0.03 0.02 to 0.05 P < 0.001 |

0.01 −0.01 to 0.02 P = 0.51 |

| Teamwork Across Hospital Units | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.05 −0.13 to 0.02 P = 0.14 |

0.01 −0.07 to 0.08 P = 0.89 |

0.11 0.04 to 0.18 P = 0.003 |

0.12 0.05 to 0.19 P = 0.001 |

0.15 0.08 to 0.22 P < 0.0001 |

−0.05 −0.12 to 0.02 P = 0.18 |

0.08 0.05 to 0.12 P < 0.0001 |

0.04 0.01 to 0.07 P = 0.01 |

0.03 0.01 to 0.04 P < 0.001 |

−0.01 −0.03 to 0.01 P = 0.18 |

| Hospital Handoffs & Transitions | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.02 −0.09 to 0.05 P = 0.61 |

0.01 −0.06 to 0.08 P = 0.87 |

−0.18 −0.25 to −0.11 P < 0.0001 |

−0.20 −0.27 to −0.13 P < 0.0001 |

0.06 −0.01 to 0.13 P = 0.08 |

−0.04 −0.11 to 0.02 P = 0.21 |

−0.06 −0.09 to −0.03 P < 0.001 |

−0.09 −0.12 to −0.06 P < 0.0001 |

0.01 0 to 0.02 P = 0.10 |

−0.01 −0.03 to 0.01 P = 0.22 |

| Department PSC | |||||||||||

| Teamwork Within Units | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.01 −0.08 to 0.07 P = 0.84 |

0 −0.07 to 0.07 P = 0.94 |

0.04 −0.03 to 0.11 P = 0.31 |

−0.02 −0.09 to 0.06 P = 0.64 |

0.10 0.03 to 0.17 P = 0.004 |

0.08 0.01 to 0.15 P = 0.02 |

0.04 0.01 to 0.07 P = 0.01 |

0.01 −0.02 to 0.04 P = 0.47 |

0.02 0 to 0.03 P = 0.01 |

0.02 0 to 0.04 P = 0.02 |

| Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.06 −0.13 to 0.01 P = 0.10 |

0.06 −0.01 to 0.13 P = 0.11 |

0.02 0.05 to 0.09 P = 0.53 |

0.0 −0.08 to 0.07 P = 0.90 |

0.23 0.16 to 0.29 P < 0.0001 |

0.09 0.02 to 0.16 P = 0.01 |

0.07 0.03 to 0.1 P < 0.001 |

0.02 −0.01 to 0.05 P = 0.25 |

0.04 0.02 to 0.06 P < 0.0001 |

0.02 0 to 0.04 P = 0.02 |

| Nonpunitive Response to Error | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.01 −0.08 to 0.06 P = 0.74 |

−0.05 −0.12 to 0.02 P = 0.17 |

0.08 0.01 to 0.16 P = 0.02 |

−0.02 −0.09 to 0.06 P = 0.67 |

0.18 0.11 to 0.25 P < 0.0001 |

0.12 0.05 to 0.19 P < 0.001 |

0.08 0.05 to 0.11 P < 0.0001 |

0.02 −0.01 to 0.05 P = 0.21 |

0.03 0.01 to 0.05 P < 0.001 |

0.03 0.01 to 0.05 P = 0.002 |

| Supervisor Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety | St. effect 95% CI P |

0.05 −0.02 to 0.12 P = 0.19 |

0.07 0.0 to 0.14 P = 0.06 |

−0.07 −0.15 to 0 P = 0.045 |

−0.03 −0.1 to 0.04 P = 0.42 |

0.13 0.07 to 0.2 P < 0.0001 |

0.09 0.03 to 0.16 P = 0.007 |

0.00 −0.03 to 0.04 P = 0.84 |

0.01 −0.02 to 0.04 P = 0.59 |

0.02 0.01 to 0.04 P = 0.002 |

0.02 0.01 to 0.04 P = 0.01 |

| Feedback & Communication About Error | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.08 −0.15 to −0.01 P = 0.02 |

0.03 −0.04 to 0.1 P = 0.46 |

−0.06 −0.13 to 0.01 P = 0.11 |

−0.09 −0.16 to −0.01 P = 0.02 |

0.20 0.14 to 0.27 P < 0.0001 |

0.11 0.04 to 0.17 P = 0.002 |

0.03 −0.01 to 0.06 P = 0.12 |

−0.01 −0.04 to 0.02 P = 0.44 |

0.04 0.02 to 0.05 P < 0.001 |

0.03 0.01 to 0.05 P = 0.005 |

| Communication Openness | St. effect 95% CI P |

−0.05 −0.12 to 0.02 P = 0.18 |

0.04 −0.03 to 0.11 P = 0.25 |

−0.21 −0.28 to −0.14 P < 0.0001 |

−0.12 −0.2 to −0.05 P < 0.001 |

0.17 0.1 to 0.23 P < 0.0001 |

0.02 −0.05 to 0.09 P = 0.60 |

−0.05 −0.08 to −0.01 P = 0.009 |

−0.05 −0.08 to −0.02 P = 0.003 |

0.03 0.01 to 0.05 P < 0.001 |

0.00 −0.01 to 0.02 P = 0.60 |

| Staffing | St. effect 95% CI P |

0.07 0 to 0.14 P = 0.04 |

−0.03 −0.11 to 0.04 P = 0.34 |

0.19 0.12 to 0.26 P < 0.0001 |

−0.06 −0.13 to 0.02 P = 0.13 |

0.11 0.04 to 0.17 P = 0.001 |

0.02 −0.05 to 0.08 P = 0.65 |

0.11 0.07 to 0.14 P < 0.0001 |

−0.02 −0.05 to 0.01 P = 0.20 |

0.02 0.01 to 0.03 P = 0.007 |

0.00 −0.01 to 0.02 P = 0.65 |

Statistically significant effects (P < 0.05) are presented in bold.

*For managerial function only direct effect is presented, as its indirect effect was not included in the model.

CI indicates confidence interval; NA, effect not included in the research model; St. effect, standardized effect.

Profession had significant effect on managerial function in both samples, with physicians being more likely to report managerial functions compared with nurses. Similarly, in both samples, gender had significant direct effect on profession and managerial function, indicating that males were more likely to be physicians and more likely to have managerial functions. Through affecting managerial function, profession had significant indirect effect on all PSC dimensions that managerial function had significant direct effect on. Similarly, by effecting both profession and managerial function, gender had significant indirect effect on nine and five PSC dimensions, respectively.

Effect of Participant Characteristics on How Different PSC Dimensions Influence Overall Perception of Patient Safety

The eight separate multiple linear regressions for the eight groups of participants (gender × profession × managerial function) in two samples revealed variation in regression coefficients across the different employee groups. Table 4 presents the results for the 16 regression models.

TABLE 4.

Results of Multiple Linear Regression in Eight Participant Groups Using Overall Perception of Patient Safety as Dependent Variable, and ten PSC Dimensions as Independent variables

| Sample | Sample A | Sample B | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Managerial function | No managerial functions | With managerial functions | No managerial functions | With managerial functions | |||||||||||||

| Profession | Nurse | Physician | Nurse | Physician | Nurse | Physician | Nurse | Physician | |||||||||

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| Employee group | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| n | 406 | 67 | 121 | 115 | 49 | 20 | 36 | 82 | 458 | 80 | 49 | 41 | 122 | 31 | 36 | 73 | |

| R2 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.76 | |

| RMSE | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.44 | |

| Intercept | Estimate 95% CI P |

−0.05 −0.45 to 0.35 P = 0.80 |

−0.76 −1.56 to 0.04 P = 0.06 |

−0.30 −1.07 to 0.46 P = 0.43 |

−0.06 −0.68 to 0.56 P = 0.85 |

−0.36 −2 to 1.27 P = 0.66 |

1.32 −1.61 to 4.24 P = 0.33 |

−0.19 −1.07 to 0.69 P = 0.66 |

0.44 −0.41 to 1.29 P = 0.30 |

−0.41 −0.78 to −0.03 P = 0.033 |

−0.83 −1.87 to 0.21 P = 0.12 |

0.00 –1.09 to 1.08 P = 0.99 |

0.25 –1.12 to 1.62 P = 0.71 |

−0.03 −0.96 to 0.91 P = 0.96 |

−0.43 −2.42 to 1.56 P = 0.66 |

−1.20 −2.37 to −0.04 P = 0.044 |

−0.07 −0.86 to 0.73 P = 0.87 |

| Hospital PSC | |||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety | β 95% CI P |

0.19 0.11 to 0.27 P < 0.0001 |

−0.10 −0.27 to 0.08 P = 0.27 |

0.21 0.03 to 0.40 P = 0.023 |

0.07 –0.09 to 0.24 P = 0.37 |

0.10 –0.15 to 0.35 P = 0.41 |

0.21 –0.23 to 0.64 P = 0.31 |

0.38 0.08 to 0.69 P = 0.016 |

0.20 0.00 to 0.41 P = 0.050 |

0.17 0.10 to 0.24 P < 0.0001 |

0.06 –0.11 to 0.23 P = 0.49 |

0.16 –0.08 to 0.40 P = 0.18 |

−0.05 −0.32 to 0.22 P = 0.71 |

0.28 0.13 to 0.43 P < 0.001 |

0.31 0.06 to 0.56 P = 0.017 |

−0.13 −0.43 to 0.17 P = 0.39 |

0.00 –0.19 to 0.19 P = 0.98 |

| Teamwork Across Hospital Units | β 95% CI P |

0.06 –0.05 to 0.18 P = 0.29 |

0.28 0.01 to 0.55 P = 0.043 |

0.07 –0.15 to 0.29 P = 0.54 |

−0.13 −0.32 to 0.06 P = 0.17 |

0.01 –0.34 to 0.36 P = 0.95 |

−0.27 −1.57 to 1.02 P = 0.64 |

−0.23 −0.60 to 0.13 P = 0.20 |

−0.01 −0.31 to 0.30 P = 0.97 |

0.02 –0.09 to 0.12 P = 0.72 |

0.06 –0.22 to 0.34 P = 0.67 |

−0.20 −0.51 to 0.10 P = 0.19 |

0.32 –0.14 to 0.77 P = 0.17 |

−0.07 −0.32 to 0.18 P = 0.60 |

−0.16 −0.50 to 0.19 P = 0.36 |

0.39 0.02 to 0.76 P = 0.037 |

−0.07 −0.39 to 0.25 P = 0.66 |

| Hospital Handoffs & Transitions | β 95% CI P |

0.08 –0.03 to 0.18 P = 0.17 |

0.08 –0.15 to 0.31 P = 0.50 |

0.14 –0.07 to 0.35 P = 0.20 |

0.07 –0.11 to 0.26 P = 0.44 |

0.18 –0.11 to 0.47 P = 0.22 |

−0.25 −1.12 to 0.63 P = 0.54 |

0.06 –0.21 to 0.33 P = 0.65 |

−0.02 −0.26 to 0.22 P = 0.88 |

0.08 –0.01 to 0.17 P = 0.09 |

0.19 –0.07 to 0.46 P = 0.15 |

0.37 0.10 to 0.63 P = 0.008 |

0.30 –0.07 to 0.68 P = 0.11 |

0.24 0.01 to 0.47 P = 0.045 |

−0.01 −0.38 to 0.36 P = 0.96 |

0.08 –0.25 to 0.41 P = 0.62 |

0.15 –0.05 to 0.34 P = 0.13 |

| Department PSC | |||||||||||||||||

| Teamwork Within Units | β 95% CI P |

0.03 –0.06 to 0.13 P = 0.48 |

0.06 –0.19 to 0.30 P = 0.64 |

−0.08 −0.28 to 0.12 P = 0.42 |

−0.07 −0.24 to 0.10 P = 0.42 |

−0.05 −0.35 to 0.24 P = 0.72 |

−0.07 −0.83 to 0.68 P = 0.83 |

0.04 –0.27 to 0.35 P = 0.80 |

−0.07 −0.32 to 0.18 P = 0.60 |

0.04 –0.05 to 0.13 P = 0.38 |

0.11 –0.14 to 0.36 P = 0.40 |

0.03 –0.24 to 0.29 P = 0.84 |

−0.22 −0.68 to 0.24 P = 0.34 |

0.02 –0.2 to 0.24 P = 0.85 |

0.29 –0.25 to 0.83 P = 0.27 |

0.16 –0.17 to 0.48 P = 0.34 |

0.10 –0.12 to 0.31 P = 0.38 |

| Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement | β 95% CI P |

0.25 0.15 to 0.35 P < 0.0001 |

0.52 0.30 to 0.75 P < 0.0001 |

0.23 0.02 to 0.45 P = 0.034 |

0.45 0.24 to 0.66 P < 0.0001 |

0.48 0.18 to 0.78 P = 0.002 |

−0.39 −1.29 to 0.51 P = 0.35 |

0.30 –0.05 to 0.66 P = 0.09 |

0.12 –0.09 to 0.33 P = 0.25 |

0.30 0.21 to 0.40 P < 0.0001 |

0.33 0.08 to 0.57 P = 0.009 |

0.23 −0.09 to 0.56 P = 0.15 |

0.41 0.02 to 0.79 P = 0.04 |

0.19 −0.05 to 0.42 P = 0.12 |

0.07 −0.35 to 0.49 P = 0.73 |

0.31 −0.21 to 0.83 P = 0.23 |

0.18 −0.07 to 0.42 P = 0.15 |

| Nonpunitive Response to Error | β 95% CI P |

−0.01 −0.08 to 0.06 P = 0.81 |

0.05 −0.09 to 0.18 P = 0.51 |

0.05 −0.12 to 0.23 P = 0.53 |

0.21 0.07 to 0.36 P = 0.005 |

0.12 −0.13 to 0.36 P = 0.33 |

0.29 −0.53 to 1.11 P = 0.45 |

−0.16 −0.52 to 0.20 P = 0.37 |

0.14 −0.07 to 0.34 P = 0.19 |

0.13 0.06 to 0.20 P < 0.001 |

0.15 0.02 to 0.28 P = 0.028 |

0.04 −0.17 to 0.26 P = 0.67 |

0.02 −0.25 to 0.29 P = 0.87 |

0.05 −0.16 to 0.26 P = 0.65 |

0.32 −0.05 to 0.69 P = 0.09 |

0.07 −0.20 to 0.33 P = 0.61 |

0.05 −0.13 to 0.24 P = 0.57 |

| Supervisor Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety | β 95% CI P |

0.05 −0.04 to 0.13 P = 0.30 |

0.07 −0.12 to 0.26 P = 0.45 |

−0.01 −0.20 to 0.19 P = 0.95 |

0.20 0.02 to 0.39 P = 0.034 |

0.10 −0.19 to 0.40 P = 0.49 |

−0.05 −0.57 to 0.48 P = 0.84 |

0.11 −0.20 to 0.43 P = 0.46 |

0.18 −0.04 to 0.39 P = 0.11 |

0.08 0.01 to 0.15 P = 0.017 |

0.08 −0.13 to 0.28 P = 0.48 |

0.04 −0.29 to 0.37 P = 0.82 |

0.13 −0.19 to 0.44 P = 0.43 |

0.06 −0.11 to 0.23 P = 0.50 |

0.10 −0.39 to 0.59 P = 0.68 |

0.41 0.01 to 0.80 P = 0.043 |

0.22 0.00 to 0.43 P = 0.050 |

| Feedback & Communication About Error | β 95% CI P |

0.04 –0.04 to 0.12 P = 0.31 |

0.03 –0.21 to 0.26 P = 0.82 |

0.13 –0.04 to 0.30 P = 0.14 |

0.05 –0.12 to 0.21 P = 0.59 |

0.02 –0.24 to 0.28 P = 0.87 |

0.66 –0.08 to 1.39 P = 0.07 |

−0.08 −0.41 to 0.26 P = 0.65 |

0.10 –0.13 to 0.34 P = 0.38 |

0.00 –0.07 to 0.06 P = 0.90 |

0.12 –0.04 to 0.28 P = 0.15 |

0.10 –0.10 to 0.29 P = 0.31 |

−0.02 −0.29 to 0.25 P = 0.87 |

−0.02 −0.22 to 0.17 P = 0.82 |

0.21 –0.06 to 0.48 P = 0.13 |

0.04 –0.26 to 0.34 P = 0.77 |

0.13 –0.10 to 0.37 P = 0.27 |

| Communication Openness | β 95% CI P |

0.00 –0.10 to 0.09 P = 0.97 |

−0.11 −0.34 to 0.12 P = 0.35 |

0.05 −0.12 to 0.21 P = 0.60 |

0.02 −0.17 to 0.21 P = 0.84 |

−0.13−0.45 to 0.20 P = 0.43 |

−0.06 −0.74 to 0.61 P = 0.84 |

0.34 0.0 to 0.69 P = 0.052 |

−0.02 −0.27 to 0.23 P = 0.88 |

0.05 −0.03 to 0.13 P = 0.21 |

−0.14 −0.35 to 0.06 P = 0.17 |

0.22 −0.04 to 0.49 P = 0.10 |

−0.11 −0.55 to 0.32 P = 0.60 |

0.06 −0.16 to 0.29 P = 0.57 |

−0.23 −0.72 to 0.25 P = 0.33 |

−0.10 −0.52 to 0.32 P = 0.62 |

0.04 −0.21 to 0.28 P = 0.77 |

| Staffing | β 95% CI P |

0.35 0.28 to 0.43 P < 0.0001 |

0.44 0.28 to 0.59 P < 0.0001 |

0.38 0.22 to 0.54 P < 0.0001 |

0.21 0.05 to 0.37 P = 0.012 |

0.28 0.06 to 0.49 P = 0.014 |

0.43 −0.15 to 1.02 P = 0.13 |

0.34 0.10 to 0.57 P = 0.007 |

0.28 0.10 to 0.46 P = 0.003 |

0.24 0.18 to 0.30 P < 0.0001 |

0.30 0.13 to 0.47 P = 0.001 |

0.08 −0.09 to 0.25 P = 0.36 |

0.25 0.00 to 0.50 P = 0.051 |

0.21 0.08 to 0.34 P = 0.003 |

0.18 −0.15 to 0.50 P = 0.27 |

0.16 −0.07 to 0.40 P = 0.16 |

0.33 0.17 to 0.49 P < 0.001 |

Statistically significant effects (P < 0.05) are presented in bold.

β – an estimated change in Overall Perception of Patient Safety in response to one-point change in independent variable.

CI indicates confidence interval; RMSE, root mean squared error.

In both samples, the PSC dimensions Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement and Staffing most frequently had strong effects on Overall Perception of Patient Safety, especially for participant groups without managerial functions. The dimension Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety more often had a significant effect in female groups compared with male groups. The four dimensions Teamwork Across Hospital Units, Hospital Handoffs & Transitions, Nonpunitive Response to Error, and Supervisor Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety had only limited effect on Overall Perception of Patient Safety in some participant groups. Finally, three PSC dimensions did not have significant effects for any of the employee groups. All statistically significant effects were positive, meaning that more positive perceptions in these PSC dimensions were associated with more positive Overall Perception of Patient Safety.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that participant characteristics may not only have significant influence on perceptions of PSC and its different aspects but also on how employees evaluate patient safety. In our study, managerial function and profession had significant effects on perceptions of PSC. Participants’ gender had very limited significant direct effect on the PSC dimensions but demonstrated considerable indirect effect through influencing profession and managerial function. Regression analyses demonstrated similarities and differences between various employee groups regarding which aspects of PSC influence Overall Perception of Patient Safety of staff.

Based on our analysis, employees with managerial function reported more positive perceptions on PSC dimensions in both samples. Similar findings were reported by several PSC studies.8–11 However, in our study, this difference was more prevalent in one sample indicating that the divergence of attitudes of managerial and nonmanagerial staff may not be the same in different countries.

In both samples, participants’ profession had significant effect on perceptions of PSC. This is in line with other studies reporting different perceptions of physicians and nurses regarding PSC.7,8,20 A recent study of measurement equivalence found that these interprofessional differences can represent true difference in the underlying concept.21 This difference may be explained by the fact that nurses and physicians in the same team have different management structures. Similar effects have been observed for perceptions of teamwork and collaboration.22 In contrast to managerial function, the difference between physicians and nurses did not always have the same direction pointing at potentially different priorities and professional values with regard to patient safety. Interestingly, the effect of participants’ profession was relatively similar in two samples.

A strong direct effect of participants’ gender on perceptions of PSC was not observed. However, gender had significant direct effects on both profession and managerial function in both samples and consequently demonstrated significant indirect effects on the PSC dimensions. These results may reflect prevalent gender gaps in healthcare, especially in managerial functions. A study in four European countries found that although gender representation is relatively balanced among medical students and medical doctors in general, females are less well represented in leadership positions.23

Our results further demonstrate that for various employee groups different aspects of PSC may be significantly related to their Overall Perception of Patient Safety. In both samples, the PSC dimensions Staffing and Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement most frequently had a strong significant effect. For female nurses and physicians without managerial functions, perceptions of Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety had a stronger effect on Overall Perception of Patient Safety than for males, where this effect was not statistically significant. Three dimensions, Teamwork Within Units, Feedback & Communication About Error, and Communication Openness, did not have significant influence on Overall Perception of Patient Safety. Another Swiss study reported no effect of the same dimensions on Overall Perception of Patient Safety, neither for physicians nor for nurses.16 This result is unexpected and difficult to explain, because better teamwork and communication have been found to be associated with safety outcomes1,24 and thus are targets of many interventions designed to improve safety culture and ultimately patient safety. Perhaps precisely because of continuous interventions in these areas, we find relatively homogenous rates in these dimensions, causing diminished effects in regression analyses. A study by Najjar et al.25 reported similar results for Belgium—Feedback and Communication Openness About Error (combined dimension) and Teamwork Within Units had a relatively low effect on Overall Perception of Patient Safety, whereas Staffing and Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety had the strongest effects. For the Palestinian sample in the same study, the effect of these dimensions was stronger but there was no significant effect of Staffing.25

Patient safety culture studies often provide benchmarks for healthcare managers.3–5,20 Our results demonstrate that when comparing results across different settings, the sample composition should be accounted for. The results of this study underline the significance of participant characteristics for perceptions of PSC and consequently the importance of fully reporting sample characteristics when publishing results. However, the differences in PSC among different employee groups may not be just a matter of transparent reporting and interpretation. In a recent article, Mannion and Davies26 discussed the existence, sources, and influence of divergent subcultures within healthcare organizations, underlining the importance of understanding and appreciating these for further improvement in PSC.

Our results support evidence on differences in perceptions of PSC between professional groups, and they should be acknowledged to adequately evaluate, understand, and affect hospitals’ PSC. However, these differences in our two study samples were not the same. Thus, further research is required to discover whether or not the presence and magnitude of the differences between employee groups influences hospital PSC or even safety outcomes. Moreover, our results support the recommendation to routinely study PSC to support hospital managers in effectively planning interventions to improve PSC while considering the current needs of specific members of clinical team.

Limitations

Although we analyzed large samples from two European healthcare systems, our results should not be generalized for all hospital employees because we only included physicians and nurses. Our inclusion and exclusion criteria, together with the somewhat low response rate among study participants, may have introduced a selection bias. This study is also subject to common method bias. Future studies should aim to confirm our findings with objectively measured safety outcomes, because the direct association between PSC and objective safety outcomes is still being debated. However, a number of studies have demonstrated correlations between PSC dimensions and objective outcomes such as mortality or readmissions.27 Finally, when establishing the path analysis model we assumed that gender may influence profession and managerial function and that profession may influence managerial function. Analyses using different conceptual models may obtain different results.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that participant characteristics have significant effects on clinical staff perceptions of different aspects of PSC and thus should be accounted for in reporting, interpreting, and comparing results obtained in different samples. Moreover, employee characteristics may also modulate the influence of specific PSC dimensions on Overall Perception of Patient Safety. However, the effects of participant characteristics in different settings may not be the same. Thus, these effects should be locally studied to better plan targeted improvement initiatives. Further studies are required to determine what effects these dissimilarities between perceptions of different employee groups have on objective patient safety outcomes and, if so, whether or not they can be influenced through targeted interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all study participants. The authors also thank We acknowledge the hospital management and the workers’ council for the support, local study coordinators for the efforts in participating hospitals to facilitate data collection, and the respondents for their effort and time to fill in the surveys.

Footnotes

The WorkSafeMed study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ 01GY1325A, 01GY1325B). The work of the Institute of Occupational and Social Medicine and Health Services Research Tübingen is supported by an unrestricted grant of the employers’ association of the metal and electric industry Baden-Württemberg. The authors acknowledge additional financial support from the German Research Foundation and the administrative support from the DLR Project Management Agency. The study in Switzerland was funded by the University Hospital Zurich. The data analysis and preparation of the publication was conducted with support of the German Academic Exchange Service awarded to N.G.

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

WorkSafeMed Consortium: Luntz E, Rieger MA (project lead), Sturm H, Wagner A (Institute of Occupational and Social Medicine and Health Services Research, University Hospital of Tuebingen), Hammer A, Manser T (Institute for Patient Safety, University Hospital Bonn), Martus P (Institute for Clinical Epidemiology and Applied Biometry, University Hospital of Tuebingen), and Holderied M (University Hospital Tuebingen).

Contributor Information

Antje Hammer, Email: Antje.Hammer@ukbonn.de.

Anke Wagner, Email: Anke.Wagner@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

Monika A. Rieger, Email: Monika.Rieger@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

Mareen Brösterhaus, Email: Mareen.Broesterhaus@ukbonn.de.

Amanda Van Vegten, Email: Amanda.VanVegten@usz.ch.

Tanja Manser, Email: tanja.manser@fhnw.ch.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waterson P, ed. Patient Safety Culture: Theory, Methods, and Application. Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: Ashgate; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mannion R, Konteh FH, Davies HT. Assessing organisational culture for quality and safety improvement: a national survey of tools and tool use. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammer A, Manser T. The use of the hospital survey on patient safety culture in Europe. In: Waterson P, ed. Patient Safety Culture: Theory, Methods, and Application. Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: Ashgate; 2014:229–262. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner C Smits M Sorra J, et al. Assessing patient safety culture in hospitals across countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristensen S Sabroe S Bartels P, et al. Adaption and validation of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire for the Danish hospital setting. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:149–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carney BT Mills PD Bagian JP, et al. Sex differences in operating room care giver perceptions of patient safety: a pilot study from the Veterans Health Administration Medical Team Training Program. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okuyama JHH, Galvao TF, Silva MT. Healthcare professional’s perception of patient safety measured by the hospital survey on patient safety culture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2018;2018:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen S Hammer A Bartels P, et al. Quality management and perceptions of teamwork and safety climate in European hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer SJ Gaba DM Geppert JJ, et al. The culture of safety: results of an organization-wide survey in 15 California hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter JP, McAlearney AS, Pennell ML. Evaluating the effect of safety culture on error reporting: a comparison of managerial and staff perspectives. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30:550–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristensen S Túgvustein N Zachariassen H, et al. The virgin land of quality management: a first measure of patient safety climate at the National Hospital of the Faroe Islands. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2016;8:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danielsson M Nilsen P Rutberg H, et al. A national study of patient safety culture in hospitals in Sweden. J Patient Saf. 2017. Available at: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000369. Accessed March 4, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guldenmund FW. The nature of safety culture: a review of theory and research. Saf Sci. 2000;34:215–257. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorra JS, Nieva VF. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. Rockville, MD: Rockville, MD: AHRQ Publication No. 04–0041; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gambashidze N Hammer A Brösterhaus M, et al. Evaluation of psychometric properties of the German Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture and its potential for cross-cultural comparisons: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfeiffer Y, Manser T. Development of the German version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: dimensionality and psychometric properties. Saf Sci. 2010;48:1452–1462. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wirtz M. On the problem of missing data: how to identify and reduce the impact of missing data on findings of data analysis [in German]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2004;43:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hair JF Black WC Babin BJ, et al. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Los Angeles [i 5 pozostałych]: Sage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Famolaro T Yount N Hare R, et al. Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture: 2018 User Database Report; (Prepared by Westat, Rockville, MD, under Contract No. HHSA 290201300003C). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018: Publication No. 18-0025-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu J. Measurement equivalence of patient safety climate in Chinese hospitals: can we compare across physicians and nurses? Int J Qual Health Care. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhlmann E Ovseiko PV Kurmeyer C, et al. Closing the gender leadership gap: a multi-centre cross-country comparison of women in management and leadership in academic health centres in the European Union. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Najjar S Baillien E Vanhaecht K, et al. Similarities and differences in the associations between patient safety culture dimensions and self-reported outcomes in two different cultural settings: a national cross-sectional study in Palestinian and Belgian hospitals. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannion R, Davies H. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. BMJ. 2018;363:k4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiCuccio MH. The Relationship Between Patient Safety Culture and Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Patient Saf. 2015;11:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]