Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: Veterans, community care, network adequacy, access

Abstract

Background:

Congress has enacted 2 major pieces of legislation to improve access to care for Veterans within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). As a result, the VA has undergone a major transformation in the way that care is delivered to Veterans with an increased reliance on community-based provider networks. No studies have examined the relationship between VA and contracted community providers. This study examines VA facility directors’ perspectives on their successes and challenges building relationships with community providers within the VA Community Care Network (CCN).

Objectives:

To understand who VA facilities partner with for community care, highlight areas of greatest need for partnerships in various regions, and identify challenges of working with community providers in the new CCN contract.

Research Design:

We conducted a national survey with VA facility directors to explore needs, challenges, and expectations with the CCN.

Results:

The most common care referred to community providers included physical therapy, chiropractic, orthopedic, ophthalmology, and acupuncture. Open-ended responses focused on 3 topics: (1) Challenges in working with community providers, (2) Strategies to maintain strong relationships with community providers, and (3) Re-engagement with community providers who no longer provide care for Veterans.

Conclusions:

VA faces challenges engaging with community providers given problems with timely reimbursement of community providers, low (Medicare) reimbursement rates, and confusing VA rules related to prior authorizations and bundled services. It will be critical to identify strategies to successfully initiate and sustain relationships with community providers.

In recent years, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has undergone a major transformation in the way that care is delivered to Veterans. In response to highly publicized concerns regarding Veterans’ access to care in VA, Congress enacted the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law 113–146) [Veterans Choice Program (VCP)] to improve access to timely, high-quality health care for Veterans.1 More recently, Congress replaced VCP with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018, which provides more choices about whether to use VA or community care and robust care coordination for Veterans using a consolidated program. To implement expanded access to care, under both VCP and MISSION, VA contracts with Third-Party Administrators (TPAs) to use their network of community providers for Veteran care.

VA’s increased reliance on community provider networks represents a new era in VA care. Recent estimates suggested that more than one third of VA-enrolled Veterans used community care under Veterans Choice Act (VCA),2,3 and current estimates suggest that more than 2.6 million Veterans were referred to community providers in the first 18 months since MISSION enactment (VA Office of Community Care, personal communication, October 27, 2020) in June 2019. Before the enactment of VCP and MISSION, nearly all Veteran care was provided within the VA. When a particular service was not available due to facility size, rurality, or complexity of services offered at that VA, Veterans were often sent to the next closest VA, which could be geographically distant from the Veteran’s local VA. If the distance to the nearest VA was too great, Veterans were allowed to use local fee basis providers on a limited basis.

The MISSION Act represents a major departure from previous VA policy that utilized community providers as a last resort, included criteria that made every Veteran eligible to use community care, and allows eligible Veterans to choose to use community providers even if a VA provider is available. The MISSION Act also allows Veterans to use community-based urgent care centers that are part of the contracted network, so that Veterans have a new option for care for the treatment of minor injuries and illnesses, such as colds, sore throats, and minor skin infections. VA’s increased use of health information exchange systems allow VA providers and community providers to seamlessly share Veteran health information.4 For example, Health Share Referral Manager allows VA and community providers to manage referrals, authorizations, and payments, while Community Viewer allows community providers to view VA consults, orders, and progress reports.5 However, despite these expanded care options for Veterans, community provider reimbursement cannot exceed Medicare rates6 except in highly rural areas and states with an all-payer model, making community provider participation potentially problematic if providers are unwilling to accept the Medicare rate.7

VA’s gradual transition to community-based provider networks has given rise to additional challenges for VA and community providers alike. Recent studies have detailed problems with communication and coordination with community providers,1 sharing medical information between systems,8 billing problems for Veterans,8 barriers to medications and follow-up appointments,9 variations in delivery and quality of care, and delayed payments to community providers. Studies have also indicated that under VCP, Veterans were not able to get appointments with community providers, either due to inadequate numbers of specialty providers enrolled with the TPA in that area of the country or that providers were not accepting the VA reimbursement rate.1

To date, no studies have examined the relationships between VA providers, contracted networks, and community providers that are needed to successfully implement the expanded use of VA Community Care. This study begins that work by exploring VA facility directors’ perspectives on their successes and challenges building relationships with VA Community Care Networks (CCN) and providers under VCP and continuing with the MISSION Act. The aim of this study is to understand who VA facilities are partnering with for community care (eg, Federally Qualified Health Centers, academic medical schools), highlight types of care where there is the greatest need for partnerships in various regions, and identify challenges of working with community providers in the new CCN contract. The CCN is a group of regional-based contracts with TPAs that provide a credentialled network of community providers and pay health care claims to those providers. The CCN is being deployed throughout calendar year 2020 and will be the primary vehicle VA uses to purchase community care. The CCN replaces the Patient Centered Community Care contract.

METHODS

We conducted a national survey with VA facility directors to explore needs, challenges, and expectations with the VA CCN (Appendix A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C213). We asked facility directors to detail the most common types of care that was referred to community providers and to describe any unique relationships they had with community providers such as Federally Qualified Health Centers, Department of Defense facilities, Indian Health Services (IHS), academic medical schools, long-term care or nursing home facilities, and other community medical or mental health facilities. We also asked open-ended questions to allow facilities to elaborate on barriers to working with community care providers and any strategies they have used to re-engage with community providers who discontinued providing care to Veterans under the CCN.

We sent email invitations to all 170 VA medical center (VAMC) directors explaining the purpose of our research and asked them to complete a survey comprised of 13 questions regarding their use of Community Care. The surveys were accessed online using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform.10 We emailed each director 3 times, or until we received a response, over the course of 6 weeks in an effort to receive data from all facilities. If we did not receive a response after 3 email attempts, we concluded that the facility director was unwilling to participate in the study. This study was reviewed by the VA Connecticut Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt.

Analysis

We began by checking for response bias by comparing facility characteristics (geographic location, percent of facility patients living in a rural area, and operative complexity score) between those facilities who responded to the survey and those who did not. Rurality information was obtained from FY18 reports from the Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center. Operative complexity scores, which are assigned by the Veterans Health Administration to define the complexity of surgical capabilities at each facility, include 3 categories: standard, intermediate, and complex. Next, we examined descriptive statistics for survey responses for overall responses, for example, identifying the most common types of specialty care referred to VA Community Care. We then examined the proportion of sites that had difficulty accessing specialty care according to: (1) barriers to access providers who were accepting new patients; (2) not having providers geographically nearby; and (3) not having providers willing to accept new patients. Finally, we explored open-ended responses provided by the facilities to more fully understand the challenges experienced at individual VA facilities, using thematic analysis.11 We read open-ended survey responses closely for surface and underlying meaning, developed codes to represent units of meaning, and developed themes from these codes. All quantitative analyses were conducted in Stata 15.12

RESULTS

Overall, we received responses from 91 VAMC directors (Appendix B, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C214). One facility did not provide identifying information on the survey and another facility responded twice, and so our final analytic dataset consisted of responses from 90 VA facilities for an overall response rate of 59%. When comparing VA facilities who did and did not respond to the survey, we found no statistically significant differences in the rurality of the VA facility (Table 1). Facility directors who responded to the survey were more likely to be from facilities that have a low facility complexity score, indicating fewer specialty care services, academic affiliations, and trauma care.

TABLE 1.

Facility Characteristics for VAMC Respondents and All VAMCs* (n=170)

| Characteristic | VAMC Survey Respondents (n=87) | All Other VAMCs (n=83) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic location, n (%) | 0.77 | ||

| Rural | 14 (16.1) | 12 (14.5) | |

| Urban | 73 (83.9) | 71 (85.5) | |

| % Rural patients (mean±SD, min–max) | 32.1±3.7, 0–99 | 26.9±3.5, 0–99 | 0.30 |

| % Rural patients, n (%) | 0.41 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.4) | |

| 1–25 | 48 (55.2) | 51 (61.4) | |

| 26–50 | 19 (21.8) | 15 (18.1) | |

| 51–75 | 4 (4.6) | 5 (6.0) | |

| 76–100 | 16 (18.4) | 10 (12.1) | |

| Complexity score (combined), n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| Complex | 54 (62.1) | 67 (80.7) | |

| Intermediate | 11 (12.6) | 10 (12.1) | |

| Standard | 22 (25.3) | 6 (7.2) |

FY17 Complexity Scores; FY18 Rurality Information.

This only includes stations classified as VAMCs. Three of our participating facilities were classified as Health Care Centers and not included here.

Max indicates maximum; min, minimum; VAMC, VA medical center.

The most common types of care referred to community providers included physical therapy (70%), chiropractic (56%), orthopedic (46%), ophthalmology (39%), and acupuncture (38%) (Table 2). The most common type of community partnerships were with long-term care or nursing home facilities (62%), academic medical schools (57%), and Department of Defense facilities (25%). Forty percent of respondents noted ongoing relationships with other community-based medical and mental health providers such as primary care providers psychologists, and gynecologists. Eighty-six percent of respondents noted that at least one of their community providers refuse to work with VA because of previous billing issues where the community providers were unpaid for months or even years (Table 2). Nearly all of these facilities (96%) have tried to reengage community providers through meetings or other attempts to encourage providers to participate in the contracted network (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Survey Responses by Facility (n=89)

| VA site identification of their top 5 specialty care types referred to community care*, n (%) | |

| Physical therapy | 62 (69.7) |

| Chiropractic | 50 (56.2) |

| Orthopedic | 41 (46.1) |

| Ophthalmology | 35 (39.3) |

| Acupuncture | 34 (38.2) |

| Neurology | 24 (27.0) |

| Dermatology | 23 (25.8) |

| Pain management | 22 (24.7) |

| Cardiology | 22 (24.7) |

| Mental health care | 20 (22.5) |

| Surgery | 17 (19.1) |

| Gynecology/infertility/maternity | 15 (16.8) |

| Long-term/nursing home care | 15 (16.8) |

| Rheumatology | 7 (7.9) |

| Other | 56 (62.9) |

| Community care partnerships, n (%) | |

| Long-term care and/or nursing home facilities | 55 (61.8) |

| Academic medical schools | 51 (57.3) |

| Other community-based medical or mental health practices | 36 (40.4) |

| Department of Defense (DoD) facilities | 22 (24.7) |

| Indian Health Services (IHS) facilities | 10 (11.2) |

| Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) | 8 (9.0) |

| Regular meetings or forums with Community Care partners to apprise them on developments in VA Community Care or to educate them about issues unique to Veterans, n (%) | 50 (56.2) |

| Experienced 1 or more community partners refuse to provide services to Veterans due to billing/payment issues, n (%) | 77 (86.5) |

Each facility respondent selected their top 5.

VA indicates Veterans Affairs.

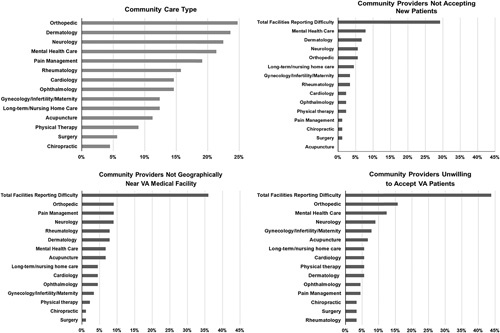

Access to community providers was most problematic for orthopedic (25%), dermatology (24%), neurology (23%), mental health (21%), and pain management (19%) (Fig. 1). For orthopedic, mental health, and neurology, the biggest barriers to access were the perceptions that community providers were unwilling to accept VA patients or that community providers were not accepting new patients. For dermatology, neurology, and pain management, access barriers were related to too few specialty care providers in that geographic areas. However, across nearly all specialty care areas examined in the survey, the most substantial barrier was that community providers were unwilling to accept VA patients, with 44% of our facilities reporting this difficulty in at least 1 specialty care area.

FIGURE 1.

Percent of facilities reporting difficulty accessing specialty care in the community: by care type and reasons* (N=89). *Reasons were not mutually exclusive; each facility could choose 0–3 reasons for each type of care. Only facilities who reported having difficulties accessing care were asked follow-up questions regarding the specific reasons. VA indicates Veterans Affairs.

Open-ended Responses to Survey Questions

To further examine how VA relationships with community providers are impacting implementation of expanded VA Community Care, we examined open-ended survey responses to questions that allowed participants to elaborate on the challenges they experienced working with community providers, and some of the strategies they used to navigate those challenges.

Challenges in Working With Community Providers

One VA facility director noted:

The biggest challenge that has affected establishment of new relationships with community providers has been the VA’s historically slow reimbursement process and the convoluted authorization and claims submission process. Many community providers became frustrated with the various payment methodologies which were often very confusing.

Directors of other VA facilities concurred with this assessment of community provider perceptions of the VA:

Our biggest challenge is the reimbursement rate and the time it takes for our community providers to get reimbursed. They are also not satisfied with our secondary authorization process, scheduling system, and the delays that they have experienced under the Choice Program.

The biggest obstacle we face to maintaining current relationships with community partners is related to claims and payment issues. Many of our partners had services authorized through our former contractor and were not paid. Therefore, they are very hesitant to continue to accept referrals from us.

Another VA facility director highlighted the contractor’s poor performance under VCP that left community providers unwilling to provide care for Veterans:

Our TPA performance with referrals, secondary authorizations and payments has limited community providers’ willingness to provide care to Veterans. The VA payment timeliness has also been a problem. The reimbursement rates (Medicare) also severely limit our ability to attract new community providers to our network.

Strategies to Maintain Strong Relationships With Community Providers

Many of the VA medical facility directors who participated in the survey discussed the strategies they used to maintain strong working relationships with community providers. Some of the VA medical facilities had had strategies such as these in place for many years, while others were developing these strategies in response to challenges in keeping community providers engaged in Veteran care. One VA facility director noted their ongoing engagement with community providers:

We provide outreach to our top community providers and meet with them regularly when needs arise or changes in programs occur. We travel to their practices and also invite them to our campus for meet and greet.

Several VAMC directors commented on their comprehensive approach to engage community providers. One VA facility leader noted:

Our VA facility conducts multiple outreaches and face-to-face meetings with community partners—providing educational materials including future planned changes/information. We also provide educational training with tools for community providers, including education on billing, viewer tools, and partnering with Health Share Referral Manager field support to provide live, face-to-face education with community providers.

Another VA facility director reported similar practices:

We have routine meetings with two of our large health care systems in the area and are beginning meetings with a third facility. The Chief of Community Care is involved as well as Community Care staff that interact most with that facility, and the referrals and authorization staff and leadership from the community partner. These meetings are typically alternating between face-to-face and phone meetings.

A third VAMC director stated:

Although we don’t currently have regular meetings, VA staff have attended town halls and given webinars for community providers to communicate upcoming changes. We also send out group emails when there is a new process that will affect them. Our strongest relationships are with rural hospitals as this is critical in Colorado for Veterans to receive quality care close to home and with mental health providers who often see Veterans for a year or more.

Re-engagement With Community Providers Who No Longer Provide Care for Veterans

With regard to trying to re-engage community providers that have decided not to work with VA, VA facility staff described multiple attempts to educate and re-engage community providers, often to no avail. In some cases, facility staff described positive experiences trying to re-engage community providers:

Our VA’s goal is to bridge the gap between the VA and our community partners by helping them navigate their authorization or billing concerns. We encourage community providers to send outstanding invoices that they have not received payment on so that the facility can do further research. We try to ensure that providers calls are returned promptly in order to re-build trust with the VA.

Another VA facility director described their efforts to re-engage community providers who were no longer willing to provide care to Veterans:

Our Community Care chief has reached out to the community facility’s CFO and Medical Director to discuss their challenges with VA payment issues and suggest amicable resolutions. The most recently hired Provider Liaison is actively engaged with reaching out to these community providers and educating them on the proposed changes and the positive effects these changes will have on Veteran’s care in the community as well as the streamlined referral and payment processes.

Other facilities had less positive experiences:

We have attempted to engage with community providers who no longer want to provide care to Veterans with face-to-face meetings to no avail.

Another director noted:

We do continued outreach via phone calls and face-to-face meetings, but when there are continued payment issues it is difficult to rebuild the relationship.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the most common types of services Veterans receive from contracted community providers, as well as the challenges VAMC directors experience in their engagement with community providers for these services. VAMC face substantial challenges engaging with some community providers given problems with timely reimbursement of community providers for services provided to Veterans, low (Medicare) reimbursement rates, and confusing VA rules related to prior authorizations and bundled services. Relationships that were developed before VCP and MISSION must now be re-established as CCN is deployed; relationships that were strained under VCP must be repaired in order to continue under MISSION. This critical strategy of stakeholder buy-in is essential for successful implementation13 of VA’s expanded community care program, especially because in some areas there are fewer alternative providers to partner with. Specifically, rural VA facilities experience challenges regarding provider shortages in underserved areas, particularly for specialty care services, but even for primary care and mental health.14–17 Taken together, these issues present substantial problems with VA’s ability to identify providers in the community willing to care for Veterans through the CCN contract.

The types of Veteran care most commonly referred to community providers (physical therapy, chiropractic, orthopedic, and acupuncture) are likely a reflection of VA’s increasing focus on providing nonpharmacologic pain care services to Veterans following the opioid crisis.18–20 Recent studies suggest that more than 50% of male Veterans and 75% of female Veterans are living with pain,21 and since the inception of the Opioid Reduction Program in 2001, VA has bolstered its nonpharmacologic pain care options.22 The passage of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016,23 in which section C called for a substantial increase in VA education, clinical services, and research on use of nonpharmacological treatments for pain, may be leading to greater use of these services.24 However, with the large number of Veterans who have been shifted from opioid medication to nonpharmacologic medications, the VA may not be able to keep pace with the demand for nonpharmacologic pain care services for Veterans living with pain. Furthermore, especially in smaller VA facilities, there may be small numbers of alternative and complementary health providers, so if providers are at capacity or if those providers leave the VA, nonpharmacologic care is referred to community providers.8

Our study echoes previous studies which demonstrate community provider shortages, particularly in rural areas.25 Despite early suggestions that waiting times for community providers were less than wait times for VA providers, evidence suggests that there are few differences in wait times in primary care and some types of specialty care.26 Recent innovations in the Office of Community Care allow Veterans to work with their VA providers to compare waiting times with both VA and community providers so that Veterans can make an informed decision regarding whether they wish to receive care in the community.

Our study also highlights tensions between community providers and VA regarding timely payments for services to Veterans that arose under VCP. Delayed VA payments impact both community providers and Veterans, who often receive bills for community health care services that the VA should cover in its benefits package.8 Recent investigations have found the VA process for appeals of non-VA care claims decisions were ineffectively managed and processed, thereby leaving Veterans at risk of becoming financially liable for wrongfully denied non-VA care claims.27 A US Government Accountability Office report in 2015 found VA claims processing significantly less timely than Medicare or TRICARE, resulting in substantial delays in payments to community providers.28 As a result of these delayed payments, some facilities in our study have reported that community providers have refused to continue to participate in the CCN. Although some VA facilities have made substantial efforts to encourage these providers to join VA contracted networks, these efforts have met with varying success. In addition, under CCN, VA’s TPAs are required to make timely payments to community providers.29

Our study also highlighted some community providers’ unwillingness to participate in the VA CCN because they are unwilling to accept the VA reimbursement rate. VA is generally limited by Congressional mandate in its ability to reimburse above the Medicare rate, with a few exceptions given to providers in highly rural communities and Alaska where there are no other providers to provide the care.30 This rate may be especially unattractive for specialists who already have relatively full panels. VA must consider marketing strategies that aim to address provider concerns regarding reimbursement rates and timely bill payments.

Taken together, the challenges highlighted by VA facility directors in this survey give rise to questions related to network adequacy in CCN. Network adequacy is a health plan’s ability to provide access to a sufficient number of primary care and specialty physicians within the plan’s network as well as all health care services included under the terms of the contract.31 MISSION legislation mandates that Veterans who must drive further than 30 minutes for primary or mental health care, or 60 minutes for specialty care may use community providers for that care. Similarly, Veterans who must wait 20 days for a primary care or mental health appointment, or 28 days for a specialty care appointment may use community care. Problems with network adequacy arise when community providers are unwilling, for reasons related to timely payments or Medicare reimbursement rates, to participate in the VA CCN, leaving Veterans with insufficient numbers or types of providers in certain geographic areas. VA did not include network adequacy standards in its VCP contracts, but all CCN contracts include specific network adequacy standards. Given known problems in access to specialists in rural areas, it is likely that rural Veterans will experience network adequacy problems for specialty care services.15,32

As VAMC have worked to implement expanded VA Community Care, many facilities have devoted additional time and effort to develop and enhance relationships with community providers to ensure greater health care access for Veterans. Although contractors provided access to a “network” of providers, provider participation was not guaranteed and challenges during VCP implementation are still being felt under MISSION. VAs have developed a variety of practices to promote positive community relationships include regular meetings with community partners, traveling to them as well as inviting them to the VA facilities, and being proactive in providing regular updates regarding VA. These practices could be disseminated to other VA facilities as “best practices” for engagement with community partners.

Our study is not without limitations. Although our survey response rate was favorable, facilities who participated in our survey were more likely to be facilities with fewer specialty care services, but these represent facilities that are more likely to rely more heavily on community providers. Therefore, our study may not be representative of large, urban VA medical facilities who are able to provide a majority of specialty care services within the VA, but they represent those facilities most likely to leveraging the CCN.

Despite these limitations, this study is an important step in identifying challenges in VA’s relationships with its community providers and how VA is addressing those challenges. As more Veterans use community care under the MISSION Act, it will be critical to identify strategies that VA can use to successfully initiate and sustain relationships with community providers. Identifying and disseminating successful strategies (ie, “best practices”) is the next step in this research trajectory.14 However, establishing VA-community partnerships is necessary but not sufficient condition for delivering “the right care, at the right time, from the right provider”33 for Veterans. Additional research is needed when relationships cannot be forged; particularly in rural areas that have poor network adequacy due to provider shortages. This study also highlights the importance of having greater knowledge about community care providers’ ability to accept new patients and their appointment wait times when Veterans and their providers are deciding whether to seek care within the VA or through VA community providers.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

Footnotes

Supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Service Directed Research (SDR) 18-319.

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy or position of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Kristin M. Mattocks, Email: Kristin.Mattocks@va.gov.

Aimee Kroll-Desrosiers, Email: aimee.kroll-desrosiers@va.gov.

Rebecca Kinney, Email: Rebecca.Kinney@va.gov.

Anashua R. Elwy, Email: rani_elwy@brown.edu.

Kristin J. Cunningham, Email: Kristin.cunningham@va.gov.

Michelle A. Mengeling, Email: michelle.mengeling@va.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, et al. The Veterans choice act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55:S71–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattocks KM, Yehia B. Evaluating the Veterans choice program: lessons for developing a high performing integrated network. Med Care. 2017;55:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Congressional Research Service. 2018. VA Maintaining Internal systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018. Available at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45390.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- 4.Whealin J, Omizo R, Lopez C. Usage of and attitudes toward health information exchange before and after system implementation in a VA Medical Center. Fed Pract. 2019;36:322–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal N. Ramifications of the VA MISSION Act of 2018 on mental health: potential implementation challenges and solutions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Veterans Affairs. 2019. Veterans Health Administration. Available at: https://www.va.gov/health/. Accessed January 16, 2020.

- 7.Department of Veterans Affairs. VA fee schedule. Available at: https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/revenue_ops/Fee_Schedule.asp. Accessed November 27, 2020.

- 8.Mattocks KM, Yano EM, Brown A, et al. Examining women Veteran’s experiences, perceptions, and challenges with the Veterans Choice Program. Med Care. 2018;56:557–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Perspectives of clinicians, staff, and Veterans in transitioning Veterans from non-VA hospitals to primary care in a single VA Healthcare System. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor B, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun VB, Clark V. Using thematic research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015:10. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinhold I, Gurtner S. Understanding shortages of sufficient health care in rural areas. Health Policy. 2014;118:201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohl ME, Carrell M, Thurman A, et al. Availability of healthcare providers for rural veterans eligible for purchased care under the Veterans Choice Act. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cyr ME, Etchin AG, Guthrie BJ, et al. Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle JM, Streeter RA. Veterans’ location in health professional shortage areas: implications for access to care and workforce supply. Health Serv Res. 2017;52:459–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:611–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin LA, Bohnert AS, Kerns RD, et al. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattocks KM, Rosen MI, Sellinger J, et al. Pain care in the Department of Veterans Affairs: understanding how a cultural shift in pain care impacts provider decisions and collaboration. Pain Med. 2020;21:970–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults—United States, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg JM, Bilka BM, Wilson SM, et al. Opioid therapy for chronic pain: overview of the 2017 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Pain Med. 2018;19:928–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.114th Congress. 2016. S. 524 (114th): Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 GovTrack. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/s524. Accessed January 22, 2020.

- 24.Kligler B, Bair MJ, Banerjea R, et al. Clinical policy recommendations from the VHA state-of-the-art conference on non-pharmacological approaches to chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacQueen IT, Maggard-Gibbons M, Capra G, et al. Recruiting rural healthcare providers today: a systematic review of training program success and determinants of geographic choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penn M, Bhatnagar S, Kuy S, et al. Comparison of wait times for new patients between the private sector and United States Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e187096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. VHA did not effectively manage appeals of non-VA care claims. 2019. Available at: https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-18-06294-213.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2020.

- 28.United States Government Accountability Office. Veterans Health Care: proper plan needed to modernize system for paying community providers. 2016. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/677051.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2020.

- 29.Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran community care: general information. 2019. Available at: https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/docs/pubfiles/factsheets/VHA-FS_MISSION-Act.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- 30.Department of Veterans Affairs. Reasonable charges for medical care or services; V3.27 and national average administrative prescription drug charge; Calendar Year 2020 Federal Register 84(244). 2019. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-12-19/pdf/2019-27325.pdf. Accessed January 2, 2020.

- 31.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. California hospital networks are narrower in Marketplace than in commercial plans, but access and quality are similar. Health Aff. 2015;34:741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattocks KM, Cunningham K, Elwy AR, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of cross-system care coordination from the VA state-of-the-art working group on VA/non-VA care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choose VA. Health care options through VA. 2019. Available at: https://www.missionact.va.gov/library/files/MISSION_Act_Community_Care_Booklet.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.