Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: Veterans, Community Care, care coordination, rural health care, systematic review

Abstract

Background:

In the unique context of rural Veterans’ health care needs, expansion of US Department of Veterans Affairs and Community Care programs under the MISSION Act, and the uncertainties of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), it is critical to understand what may support effective interorganizational care coordination for increased access to high-quality care.

Objectives:

We conducted a systematic review to examine the interorganizational care coordination initiatives that Veterans Affairs (VA) and community partners have pursued in caring for rural Veterans, including challenges and opportunities, organizational domains shaping care coordination, and among these, initiatives that improve or impede health care outcomes.

Research Design:

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to search 2 electronic databases (PubMed and Embase) for peer-reviewed articles published between January 2009 and May 2020. Building on prior research, we conducted a systematic review.

Results:

Sixteen articles met our criteria. Each captured a unique health care focus while examining common challenges. Four organizational domains emerged: policy and administration, culture, mechanisms, and relational practices. Exemplars highlight how initiatives improve or impede rural health care delivery.

Conclusions:

This is the first systematic review, to our knowledge, examining interorganizational care coordination of rural Veterans by VA and Community Care programs. Results provide exemplars of interorganizational care coordination domains and program effectiveness. It suggests that partners’ efforts to align their coordination domains can improve health care, with rurality serving as a critical contextual factor. Findings are important for policies, practices, and research of VA and Community Care partners committed to improving access and health care for rural Veterans.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is expanding Veterans’ access to high-quality health care by purchasing care from community providers through its VA Community Care Network (hereafter “Community Care”). Accelerated by the Veterans Choice Act of 20141 and VA MISSION Act of 2018,2 VA schedules ∼250,000 appointments per day within its 1255 VA facilities (71%) and another 102,000 per day for VA-purchased Community Care (29%).3 Access to both VA and Community Care is particularly crucial for rural Veterans who face unique access barriers, such as: travel distance to the nearest VA facility,4 greater need for specialty care in the community,5 and limited broadband connectivity for telehealth services.6,7 Nearly half of all rural Veterans, 2.2 million (47%), are “dual care” patients, that is, using both VA and community services.8 Studies have shown that rural, dual care Veterans are older and more clinically complex than their urban counterparts or those using a single health care system.8–11 Combine these factors with the threat of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and rural Veterans face a perfect storm in accessing and managing VA and Community Care.12,13

Equally challenging for VA and Community Care are their efforts in care coordination, defined as: “the deliberate organization of patient care activities between 2 or more participants (including the patient) involved in a patient’s care to facilitate the appropriate delivery of health care services.”14–16 As summarized in a recent study,17 improvements to interorganizational care coordination, that is, cross-system care coordination, can inadvertently complicate an already complex process.18 The authors concluded that fundamental mechanisms and relational approaches—accounting for Veteran population complexity and challenges of delivering health care in dispersed rural settings—were required. To this purpose, VA recently launched 2 initiatives laying the groundwork for improved VA Community cooperation: the VA Office of Community Care (OCC) Care Coordination Model, and the Care Coordination and Integrated Case Management Initiative (CC&ICM).3 While these programs provide a framework for cross-system coordination that could generate broad awareness of new challenges and solutions, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic review of VA Community Care coordination initiatives over the past decade of policy change that focuses on rural Veteran care. Given the unique context of rural Veterans’ health, expanded access to Community Care under the MISSION Act, and the impact of COVID-19, it is critical to gauge lessons learned in supporting effective interorganizational care coordination for improved access and care of rural Veterans. Hence, we undertook this systematic review to address:

What interorganizational care coordination challenges and opportunities do VA and Community Care partners face in caring for rural Veterans?

What types of organizational domains shape VA- Community interorganizational care coordination of rural Veterans?

Within these domains, which interorganizational care coordination interventions improve or impede health care outcomes of rural Veterans? Why?

METHODS

Search Strategy

We followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to conduct a systematic search of PubMed and Embase.19 Publications from January 1, 2009, to May 31, 2020, were searched to reflect a decade of VA Community Care interorganizational care coordination (5 y prior and 5 y subsequent to Veterans Choice enactment, inclusive of the MISSION Act) since this legislation introduced significant organizational and procedural change.20–22 Search terms and stems were derived from care coordination literature focusing on VA and Community Care, including: study population characteristics and care coordination and contextual attributes.3,11,18,23–28 Our search strategy is described in Appendix A (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C210). Our PRISMA Checklist is in Appendix B (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C211).

Study Selection

Included articles were: English-language, peer-reviewed literature that provided original quantitative and qualitative research of interorganizational care coordination of VA with Community Care of rural Veterans. Exclusion criteria eliminated: systematic reviews, letters to the editor, research letters, policy briefs, case reports, workshops, executive summaries of governmental reports, and other non-peer-reviewed publications. All references were imported into EndNote, a reference management software package.29

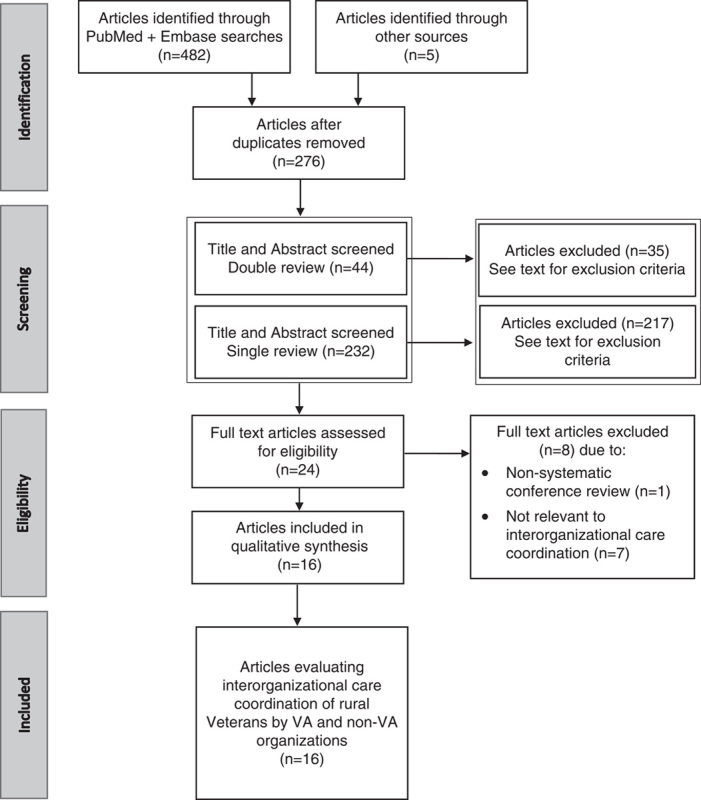

As a first step, 2 researchers (L.A.G. and M.P.) screened the titles and abstracts of all 271 unique articles identified, plus 5 studies suggested by a content expert for a total of 276 unique articles. Of these, 44 articles (16%) were screened by both researchers. Interrater reliability based on this double coding was 0.80, indicating acceptable reliability.30 Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The remaining 232 articles (86%) were split between L.A.G. and M.P. for the single screening of titles and abstracts. In total, 24 articles were considered eligible for full-text assessment. As a second step, both researchers independently read and assessed these articles, yielding 16 articles (67%) in the final synthesis, including 1 of the 5 expert-provided articles.31 Exclusions comprised 7 articles that were insufficiently relevant to care coordination and 1 nonsystematic conference review.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted from each paper by 2 researchers (L.A.G. and M.P.) and recorded in a template informed by prior work. The following data were extracted from each paper: first author, year, and legislative context of publication [ie, Pre-Choice Act (2009–2013), Choice Era (2014–2017), MISSION Era (2018–2020)]. Data extraction also included: study design and population; study setting; health care focus; and Veteran characteristics; and 5 a priori organizational domains, including: organizational mechanisms; organizational culture; relational coordination; contextual factors; and third-party administrators (TPAs). Table 1 outlines domain definitions. Finally, outcomes extracted included: access to care; health quality; quality of life; quality of care; patient safety; patient satisfaction; efficiency; and learning, innovation, and implementation, and each article’s conclusion on the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of the initiative. The 2 researchers arrived at mutually agreed upon extractions for each article.

TABLE 1.

Interorganizational Care Coordination—Domain Terms and Definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Organizational policy and administration | Organizational policy and administration are framed in written agreements or memoranda of understanding that outline the strategic purpose, goals, and scope of a program, the roles of its various organizational partners, and the funding and administration necessary for success. These may also specify performance measures, means of conflict resolution, and consequences if the agreement, or particular milestones, are not met. The organizational policy provides general statements of how partners will conduct themselves. Administrative procedures then define exactly how tasks toward strategic goals will be accomplished by whom, when, where, and how |

| Organizational culture | Organizational culture may be defined as the common values, norms, and expectations guiding organizational behavior as codified in an organization’s mission, vision, and values statement. In a comparison of 4 different health care cultures, managers in a bureaucratic culture emphasize keeping things the same and the importance of following rules. This contrasts with an entrepreneurial culture where managers encourage innovative ideas to address organizational needs. Managers in a group culture promote employee satisfaction, while those in a rational culture focus on mission |

| Organizational mechanisms | Organizational mechanisms operationalize policy. Mechanisms for coordinating care between systems include23: Roles: to support efficient, effective task assignment, monitoring and accountability Plans, procedures and rules: (eg, schedules, process flowcharts, protocols) Systems: eg, care plans, treatment summaries, visit notes, electronic health records Routines: to help make tasks visible (eg, multidisciplinary care meetings), to facilitate transition of work from one individual or group to another (eg, local care pathways), collective moments for interdependent group to work jointly on a task (eg, training, simulation) Proximity: Visibility of individuals enacting mechanisms for greater informal understanding of how to work interdependently (eg, patient and family-centered rounds) Organizational mechanisms identified in this literature included: clinical operations and personnel; communication and information sharing; information technology; the role of designated care coordinators and facilitators; and trained and aligned contract services |

| Relational practices | Relational coordination theory holds that coordination is most effectively carried out through frequent, timely, accurate, problem-solving communication among key stakeholders, supported by relationships (formal and informal) based on shared goals, shared knowledge, and mutual respect |

| Contextual factors | Contextual factors are elements external to the health care organization that nonetheless can impact effectiveness of the care and outcomes. In rural settings, poor patient population health and resources are factors. Shortage of providers, particularly in specialty care (eg, mental health, obstetrics) is another that can hinder staff recruitment and retention. Patients and providers face long travel distances, limited transportation services, and poor broadband connectivity |

| Third-party administrators | Under the Choice Act, Veterans Affairs outsourced the tasks of appointment scheduling and reimbursement for community services to third-party administrators (TPAs), eg, HealthNet, TriWest. The MISSION Act shifted TPA responsibility to reimbursement, education, and communication regarding Veterans Affairs Community Care Network providers, eg, Optum, TriWest |

As none of the final 16 articles used experimental methods, the results were quantitatively incomparable. Hence, we conducted a systematic review based on these a priori domains.32

RESULTS

Our PubMed and Embase search spanning January 2009 to May 2020 yielded 271 unique articles plus 5 expert-suggested articles for a total of 276 unique articles for the title and abstract review. Of these, 24 eligible articles received a full-text assessment and 16 articles were included (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of the study selection process. VA indicates Veterans Affairs.

Study and Participant Characteristics and Context

Table 2 outlines study and participant characteristics and context of the selected articles, including: VA-Community Care policy era, study design and population, study setting, health care focus, Veteran characteristics and contextual factors. VA Community Care policy eras represented included: 4 Pre-Choice articles,31,35,41,43 8 Choice Era articles,33,34,36–38,44,46,47 and 4 MISSION Era articles.39,40,42,45 Study designs included: 14 observational articles,31,33,35,36,38–47 and 2 descriptive articles.34,37 While all articles examined the care coordination of rural Veterans, study participants varied: 7 included Veterans,33,39,40,42–45 5 included VA providers,34,36,40,46,47 and 8 included Community Care or other non-VA providers.31,35,36,38,41,44,45,47 Study settings included: 6 National studies,33,37,39,42,44,47 6 in Northern Plains states,31,35,36,38,41,43 2 in Western states34,46 and 2 in New England states.40,45 The Veteran health care focus of VA Community programs varied greatly: 3 on American Indian Community Care,34,35,46 3 on sharing electronic health record (EHR) data,31,44,47 2 on obstetrics and maternity,39,42 1 on housing for the homeless,36 1 on treatment for opioid use,40 1 on retail immunization,33 and 5 on interorganizational care coordination itself.33,37,38,43,45

TABLE 2.

Study and Participant Characteristics and Context of VA Community Interorganizational Care Coordination of Rural Veterans

| References and Policy Era | Study Design and Population | Study Setting | Health Care Focus, Veteran Characteristics, and Contextual Factors for Included Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Botts et al33 (Choice Era) | Observational N=8809 Veterans claims | National | Retail immunization using eHealth information exchange Geographic proximity to Walgreens Pharmacy Rural dual care |

| Brooks et al35 (Pre-Choice Era) | Observational N=39 Community providers and American Indian stakeholders | Northern Plains US | American Indian Veterans Comorbid mental health Geographic distance Rural dual care |

| Cretzmeyer et al36 (Choice Era) | Observational N=39 VA and Community providers | Iowa | Housing for homeless Veterans Comorbid mental health Substance use Rural dual care Geographic distance Shortage of providers |

| Gaglioti et al38 (Choice Era) | Observational N=67 surveys N=21 interviews Non-VA providers | Iowa | Veteran-mediated health information exchange Geographic distance Rural dual care Comorbid conditions |

| Jasuja et al40 (MISSION Era) | Observational N=16,866 Veterans | Massachusetts | Dual prescribing of opioids Rural dual care Chronic pain |

| Katon et al42 (MISSION Era) | Observational N=27 women Veterans | National | Effective, but scarce obstetric Community Care Geographic distance Rural dual care |

| Klein et al44 (Choice Era) | Observational N=620 Veterans N=133 non-VA providers | National | Veteran-mediated health information exchange Primarily older, White, Vietnam era Veterans Rural dual care |

| Kramer et al46 (Choice Era) | Observational N=37 VA providers | Western US | Home-based primary care/noninstitutional long-term care American Indian Veterans Rural dual care |

| Kramer et al34 (Choice Era) | Descriptive N=37 VA providers, staff, and managers | Western US | Home-based primary care/noninstitutional long-term care American Indian Veterans Geographic distance (colocation of operations) Rural dual care |

| Lampman and Mueller31 (Pre-Choice Era) | Observational N=11 non-VA primary care providers | Nebraska | eHealth information exchange Geographic distance Rural dual care |

| Mattocks et al37 (Choice Era) | Descriptive N=43 VA providers and staff | National | Veterans Choice Act Rural dual care |

| Mattocks et al39 (MISSION Era) | Observational N=519 women Veterans | National | Perinatal women Veterans Comorbid Mental Health Trauma Rural dual care |

| Nayar et al41 (Pre-Choice Era) | Observational N=1006 Veterans | Nebraska | Veteran-mediated health information exchange Geographic proximity Rural dual care |

| Nayar et al43 (Pre-Choice Era) | Observational N=383 nonfederal physicians | Nebraska | Rural dual care |

| Schlosser et al45 (MISSION Era) | Observational N=187 Veterans N=19 VA providers N=20 Community providers | Vermont and New Hampshire | Systemic issues of communication and information sharing Rural dual care |

| Shi et al47 (Choice Era) | Observational N=41 VA providers N=69 Community providers | National | eHealth information exchange Rural dual care |

VA indicates Veterans Affairs.

In terms of contextual factors, all articles recognized the health disparities facing rural, dual care Veterans. Rural patients and providers additionally faced: long travel distances,31,33–36,38,42,43,46 poor broadband connectivity,31,33,36–38,41,44,47 and provider shortages, particularly specialty care (eg, mental health, obstetrics).36,39,42 Staff shortages contributed to difficulties in: hiring and maintaining workforces,34 patient transfers and referrals, prescribing, and provider contact.41 On the upside, rural community physicians were more likely than urban counterparts to incorporate care coordination into their clinical practice, and to follow up with Veterans postreferral to VA.41

Interorganizational Care Coordination Domains and Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the interorganizational care coordination domains and outcomes in the included studies. One a priori domain, contextual factors, represents factors external to health care organizations so was addressed in the Study and Participant Characteristics and Context section. A second, TPAs, was dropped due to insufficient reporting. One emergent domain, policy and administration, was added based on its evidence in all 16 articles and its role as a precursor to sound execution through mechanisms and relationships. Resulting domains included: (1) organizational policy and administration; (2) organizational culture; (3) organizational mechanisms; and (4) relational practices.

TABLE 3.

Domains and Outcomes of Veterans Affairs-Community Interorganizational Care Coordination of Rural Veterans

| References and Policy Era | Organizational Policy and Administration | Organizational Culture | Organizational Mechanisms | Relational Practices | Initiative Effectiveness* and Outcomes for Included Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botts et al33 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Written agreement/standard performance measures | Responsive practice | Clinical operations/personnel Shared goals and incentives Information technology Information sharing/communication | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Access to care Efficiency | |

| Brooks et al35 (Pre-Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Responsive practice Acknowledge/align cultures Responsibility to women, racial/ethnic minorities | Clinical operations/personnel Information technology Information sharing/communication | Relational coordination Leadership/frontline champions | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Access to care Learning, innovation, and implementation |

| Cretzmeyer et al36 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Responsive practice Responsibility to vulnerable populations, eg, homeless | Clinical operations/personnel Information sharing/communication | Relational coordination Informal relationships and communication | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Quality of life |

| Gaglioti et al38 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Responsive practice | Clinical operations/personnel Information technology Information sharing/communication | Relational coordination | Initiative ineffective for: Quality of care Health quality |

| Jasuja et al40 (MISSION Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Goals, resources, and needs | Designated care coordinators Information technology Information sharing/communication | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Patient safety | ||

| Katon et al42 (MISSION Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Goals, resources, and needs Codeveloped policies/pooled resources | Responsive practice Communication/collaboration Responsibility to women, racial/ethnic minorities | Clinical operations/personnel Patient training | Relational coordination | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Access to care Patient satisfaction |

| Klein et al44 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Geography Mutual understanding of organizations goals | Responsive practice Information transparency/accessibility | Information technology Basic information technology infrastructure Information technology training Information sharing/communication | Initiative effective for: Quality of care | |

| Kramer et al46 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose History/shared experience Mutual understanding of organizations goals in context of interorganizational care coordination Written agreement/standard performance measures Memoranda of understandings | Acknowledge/align cultures Responsibility to women, racial/ethnic minorities Interdisciplinary health care teams, case management, wholistic approach | Information technology Basic information technology infrastructure Interoperability and cost-competitiveness | Relational coordination | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Access to care Learning, innovation, and implementation |

| Kramer et al34 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose History/shared experience Mutual understanding of organizations goals Written agreement/standard performance measures Memoranda of understanding at outset Standardize measures of health care Codeveloped policies/pooled resources | Acknowledge/align cultures Responsibility to women, racial/ethnic minorities | Clinical operations/personnel Adequate staffing and training Clear roles and performance standards | Relational coordination Leaders/frontline champions Identify leaders that represent the community Cultivate leaders and champions Informal relationships/communication | Initiative effective for: Learning, innovation, and implementation |

| Lampman and Mueller31 (Pre-Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Codeveloped policies/pooled resources | Responsive practice Information transparency/accessibility Less risk averse and bureaucratic | Clinical operations/personnel Clear roles and performance standards Communication and information sharing Designated care coordinators | Relational coordination Leaders/frontline champions | Initiative ineffective for: Patient safety Learning, innovation, and implementation |

| Mattocks et al37 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Standard measures of performance Codeveloped policies/pooled resources Anticipate needs of frontline providers Clarify goals, roles | Responsive practice Information transparency/accessibility Communication and collaboration | Clinical operations/personnel adequate staffing and training Information technology Information sharing/communication trained, aligned contract services | Relational coordination | Initiative ineffective for: Learning, innovation, and implementation |

| Mattocks et al39 (MISSION Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose Mission/values Codeveloped policies/pooled resources Clarify goals, roles, responsibilities, and resources; performance incentives or penalties, and timelines | Responsive practice Information transparency/accessibility Communication and collaboration Responsibility to women, racial/ethnic minorities | Trained, aligned contract services | Relational coordination | Initiative ineffective for: Quality of care Access to care |

| Nayar et al41 (Pre-Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Clinical operations/personnel Adapt practices to different care settings Information technology Information sharing/communication Communicate contact points to patients | Relational coordination | Initiative ineffective for: Quality of care Access to care Patient satisfaction | |

| Nayar et al43 (Pre-Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Responsive practice Less risk averse and bureaucratic | Clinical operations/personnel Adequate staffing and training Clear roles and performance standards Information technology | Relational coordination Informal relationships/communication | Initiative ineffective for: Quality of care Efficiency |

| Schlosser et al45 (MISSION Era) | Written agreement/standard performance measures Ask new patients if they are dual care Veterans Standardizing formularies | Responsive practice | Information sharing Increase specialist communication Leverage complementarity of partner strengths | Relational coordination | Initiative ineffective for: Quality of care Access to care Patient safety Patient satisfaction |

| Shi et al47 (Choice Era) | Understanding/alignment on purpose | Responsive practice Information transparency and accessibility | Information technology Information sharing/communication | Initiative effective for: Quality of care Efficiency |

Initiative effectiveness as concluded by the authors of each individual article.

Organizational Policy and Administration

Two policy and administrative strategies deemed successful by article authors were: alignment and understanding between partners and clear contractual agreement. VA and community partners leveraged their similarity or complementarity for alignment on one or more of the following: purpose,31,33–35,38–40,46 scale,33 geography,44 or shared history or experience.35,36 For example, strong alignment of purpose and complementarity of resources was demonstrated by the VA Maternity Care Coordination Program which guarantees women Veterans maternal and perinatal care through community specialists and mental health services through VA.42

Three studies noted the advantages of contracts or memoranda of understanding in outlining the program’s goals and organizations’ roles for care coordination. The first 2 required a designated care coordinator at each site42 and mandated that VA medical centers meet annually with community agencies.36 In the third study, contracting established: the primary care provider of record, joint privileging of providers, EHR sharing, and reimbursement policy.46

Twelve articles cited onerous policy or procedures as a cause for delayed or halted care coordination. Issues facing VA and community partners included the need for: transparency and communication on credentialing and contracting31; authorization, scheduling, copayment, and reimbursement34,37,39; clarification of which organization has primary care responsibility for the Veteran31; Community Care awareness that patients were Veterans and notification to VA of care provided45; and, finally, need for standardized requirements regarding health information exchange (HIE)31,36,44 and network provider capabilities.

Organizational Culture

For organizational culture, we examined the shared beliefs, norms, and values (demonstrated or absent) between organizations. Cultural barriers were evident in 8 articles that related perception of VA’s culture as bureaucratic, insular, and risk averse,31,34,35,37,38,41,46 with 1 community physician lamenting: “VA is integrated within itself but ‘Balkanized’ with respect to outside systems.”45 Cultural differences between VA and Community Care were further complicated by VA’s rapid introduction of large, geographically distant TPAs who were unfamiliar with local clinicians, and unprepared for care coordination of complex rural Veteran patients.37

Still, cultural facilitators of care coordination were evident in 4 articles.31,34,35,46 These included VA’s combination of patient-centered care, interdisciplinary health teams, and complementary and integrative health.35,41 In 1 home-based primary program serving Native American Veterans in remote communities, VA leveraged its program’s reputation to attract new providers, despite challenging, often isolated rural work conditions. Engaging with tribal leaders allowed VA providers to learn care that was respectful of American Indian culture. In response, tribal leaders advocated for adoption of the program among Veterans in their communities.34

Organizational Mechanisms

Multiple organizational mechanisms were identified in the literature. While all clinical operations required adequate staffing, training, and resourcing, these were particularly salient for care coordination.33–35,43 Clear staff roles, performance standards and teamwork goals, and incentives33,35,36,38,47 were also critical requirements. Thirteen articles emphasized the value of timely, accurate communication and information sharing. Of these, 6 articles praised VA, particularly primary care providers, noting that communication improves when tailored to the needs of the care setting.31,36,41,42,45,47 Seven articles cited both VA and Community Care for problematic communication and information sharing, such as: lack of contact information, reliance on Veterans to convey health records between systems,41 and delayed response to requests.31,37,38,41,43,44 One community provider remarked: “information-wise it’s a black hole in space.”45

Information technology (IT) was noted in 7 articles, addressing compatible EHR systems and HIE connectivity that can facilitate accurate, reliable and efficient information sharing in care coordination.35,37,40,41,43,44,46 Partnerships benefitted when basic IT infrastructure and sufficient EHR and HIE training was in place.35,37,44,46 One article investigated the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act that requires Pain Management Provider databases across Massachusetts to provide annual updates on VA patients receiving prescriptions for controlled substances for the VA medical record, reducing unsafe dual opioid sourcing, particularly in rural communities.40 In another example, the VA Retail Immunization Coordination Project partnered with Walgreens Pharmacy, empowering Veterans to receive their seasonal flu shot at a convenient Walgreens store while quickly and accurately updating Veteran EHRs from Walgreens immunization records.33

The role of designated care coordinators and facilitators assigned at key service junctures or to high-risk patients was identified in 5 articles.31,34,39,40,42 For example, one VA program instituted a full-time Native American nurse care coordinator34 while in another, a facilitator coordinated contracted electronic HIE network completion.31 Three articles featured TPAs who brought much-needed personnel and expertise to challenging care settings.34,37,46

Relational Coordination

Relational coordination, informal relationships, and communication are themes in keeping with Gittell’s Relational Coordination Theory.48,49 In this review, 12 articles31,34–39,41–43,45,46 demonstrated the need for: shared goals, shared knowledge of others’ skills and tasks, mutual respect, and communication that was accurate, timely, frequent and addressed problem-solving between organizations and individuals.48 (We differentiate this interpersonal dialogue from task-driven or system-driven communication addressed in Organizational Mechanisms.) In an article about a shelter for formerly homeless Veterans, shared goals and knowledge of VA and community partner capabilities set positive expectations, which program administrators then successfully met through informal, personal communication and cooperation.36

Both formal and informal relationships between VA and community providers were cited as beneficial for launching and sustaining partnerships serving rural Veterans.31,34 In one article, VA and the Indian Health Service and Tribal Health Programs (IHS/THP) had a memorandum of understanding, however, the partners had few formal ties, and Veterans and tribal leaders held a deep distrust of VA.34 To address these barriers, VA providers expressed to tribal leaders the honor and personal reward they found in serving Native American Veterans. They demonstrated commitment by sustaining the program over many years, adapting to community needs. Tribal leaders responded with their endorsement, and American Indian community advocates acted as program champions, strengthening VA relations with Native American Veterans.

Six articles highlighted the role of leaders and frontline champions in building and advancing relationships for better care coordination,31,33,34,36,37,40 winning consent and sustained effort from providers and patients33–35 to streamline the introduction of care coordination initiatives. Identifying leaders that represented the community strengthened the legitimacy of the program among constituents and the enduring relationships that powered it.35

Outcomes

Studies reporting health care outcomes include: 13 articles on quality of care,33,35,36,38–47 7 on access to care,33,35,37,39,43,45,46 and 5 on learning, innovation, and implementation,31,34,35,37,46 and 3 each on patient safety,31,40,45 patient satisfaction42,43,45 and efficiency.33,41,47 One article each addressed health quality38 and quality of life.36 On the basis of the initiative effectiveness concluded by the authors of each article, there was no pattern of initiative outcomes improvement over the decade of Pre-Choice (2009–2013), Choice Era (2014–2017), and MISSION Era (2018–2020) initiatives.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review examining interorganizational care coordination of rural Veterans by VA and Community Care programs. The literature illustrates a spectrum of Veteran patient populations, Community Care, and health care focuses. It also captures the diversity of care coordination partnerships from: close coordination between VA and community providers to expand primary care among American Indian Veterans34,46 or mental health care among Veterans experiencing homelessness,36 to parallel roles played by community and VA providers in coordinating maternity and mental health care for women Veterans39,42; or from in-person efforts to bridge VA-Community information sharing,37,41,45,47 and Veteran-mediated information exchange38,43,44 to virtual coordination, strengthening Veteran telehealth,31,35 reducing opioid prescribing,40 and increasing retail immunization.33

Our review identified numerous interorganizational care coordination challenges and opportunities.

Rurality and its unique challenges for Veterans and providers is a crucial contextual factor in all 16 articles studied, manifested in its physical toll, for example, travel distances, lack of broadband for telehealth; and its social and psychological impact, for example, dedicated clinicians confronting provider shortages. However, it is the success or failure of VA and community partners to align their policies, cultures, mechanisms and relational practices that may overcome barriers toward improvement of interorganizational care coordination. Thus, VA-Community Care initiatives might focus, when possible, on bridging divides and advancing shared purpose.

First, 2 policy and administration characteristics distinguished successful care coordination programs: alignment and understanding between partners, and contractual agreement. Our literature revealed that organizations, like individuals, more naturally align with others who are similar in mission or values,31,35,36,42 in history or shared experience,6,33–35,46 or offer complementary capabilities. A critical finding, while seemingly obvious, is the need for VA and Community Care to clarify and streamline: (1) policies of credentialing, contracting, authorization, scheduling, and reimbursement; (2) performance measures; (3) notification of VA and Community providers regarding which patients are dual care Veterans; and (4) agreement on partner capabilities and roles.31,33–35,37,42,46 Unclear or onerous policies, fragmentation of services, and lack of standardized measures that fail to frame the coordination process from the start can lead to executional challenges in mechanism and relational domains, and eventually, to patient safety, care quality, and efficiency concerns.35,41,43,45

Second, VA and Community Care leaders can introduce the best (or the worst) of their organizations’ beliefs and norms into their interorganizational care coordination mission and values. VA is steadily advancing toward a proactive culture that is already evident in Community Care programs, recognizing the value of information transparency and responsiveness38; communication and collaboration47; and rewards for innovation as a learning organization. For its part, VA’s patient-centeredness is valued by Veterans and providers alike, so selecting patient-centered partners and agents would protect this cultural asset.34 VA can also share insights on the strength of its interdisciplinary teams, case management and popular holistic approach.33 Community providers can be better partners by identifying which of their new patients are Veterans and hence may be eligible for VA resources.45 VA and community partners can support Veterans of racial/ethnic minorities and women Veterans by investing time and training for cultural awareness that enables respectful relations.35,42 Successful care over time builds trust and confidence in the people and the program.

Third, for care coordination to prosper, organizational mechanisms between clinical operations must be well-tuned. Both partners can aim to provide adequate staffing and sufficient training for providers,40,47 patients,42 and TPAs37,39; establish shared goals33; clear roles and performance standards31,34,41; and provide accessible contact points for patients and providers,43 while strengthening interpersonal communication,36,41 particularly with specialists.31 In terms of IT, organizations advance when basic IT infrastructure is in place,35,44,46 with the long-term goal of interoperability with partner systems and connection to others via HIEs for accurate, efficient EHR access.44,46 VA Community partnerships can appoint designated care coordinators at key service junctures to improve information flow and process adjustments.31,40 Partners can train and align TPAs to facilitate care coordination among providers and with patients.37,39 And learning organization approaches, for example, patient and staff feedback and use of outside viewpoints, can accelerate adoption of novel care coordination approaches.31,34,35,37,46

Fourth, relational factors such as relational coordination instilled within partnerships at both executive and frontline provider levels will provide a well-informed and reciprocal work environment.34,35 Care coordination partnerships that cultivate leaders and frontline champions who can win consent and engagement from providers will enhance their chances of program success.31,48 This is particularly effective when those leaders or champions are representative of the community served, or at least, demonstrate cultural awareness and understanding.34

Finally, we observed the role of rurality to be a contextual factor in interorganizational care coordination. An earlier quantitative VA systematic review of rural versus urban health care surmised that rurality can operate as a moderator of health care organizations’: patient populations (eg, rural Veterans are typically older, sicker, and face greater access challenges); structures (eg, scarcity of providers); or processes (eg, less frequent office visits, diagnostic tests, and medical procedures), contributing to variation in health outcomes (eg, higher rates of invasive cancers and suicide).50 Our review similarly suggests that rurality is an important contextual factor influencing interorganizational care coordination’s impact on outcomes, though not the character of the coordination itself. The many challenges of rurality to patients and providers raise the stakes for why improvements to coordination are critical to improving health care and outcomes.

Limitations of this review include our inclusion and exclusion criteria which strictly focused on the study population of rural, dual care Veterans. This likely excluded a number of studies about VA interorganizational care coordination that were not specific to rural Veterans but may have applicability to rural Veterans. This also may have excluded studies focused on rural, single-system care coordination, but that may have applicability to interorganizational care coordination. And while this review did not exclude telehealth articles, telehealth terms were not among inclusion criteria, thus limiting related studies. Another limitation was that most studies included were observational, which precluded pooling of data or statistical control for unmeasured confounding. Finally, our analysis addressed interorganizational care coordination at the organizational level. Future research should focus on the roles of teams and individuals working across systems to optimize coordination.

In the unique context of rural Veterans’ health care needs, the VA’s expansion of Community Care under the MISSION Act to meet those needs, and the uncertainties of COVID-19, it is critical to understand what supports effective interorganizational care coordination for high-quality care. Our systematic review suggests that partners’ efforts to align their interorganizational care coordination domains (policies, cultures, mechanisms, and relations) within the rural context, or leverage complementary capabilities, may improve health care outcomes. While more research is needed, our interorganizational care coordination findings are important for the policies and practices of VA and Community Care partners committed to improving access and health care outcomes for rural Veterans.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Matthew P. Vincenti, Pamela W. Lee, Richard E. Lee, and Bradley V. Watts for their insights and scholarly review. They are also grateful to Jason Smith, MLIS, Medical Librarian, VA VISN1 Knowledge Information Service, who conducted the search and assisted in search strategies.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the VHA Office of Rural Health. Additional support for M.P. was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (T32MH018261).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Lynn A. Garvin, Email: Lynn.Garvin@va.gov;lagarvin@bu.edu.

Marianne Pugatch, Email: Marianne.Pugatch@ucsf.edu.

Deborah Gurewich, Email: Deborah.Gurewich@va.gov.

Jacquelyn N. Pendergast, Email: jacquelyn.pendergast@va.gov.

Christopher J. Miller, Email: Christopher.Miller8@va.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.United States Congress House of Representatives. 113th Congress 2nd Session. H.R. 3230. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014. [Became Public Law No: 113-146]; 2014.

- 2.House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs. The VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act); 2018.

- 3.Greenstone CL, Peppiatt J, Cunningham K, et al. Standardizing care coordination within the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:S4–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hynes DM, Koelling K, Stroupe K, et al. Veterans’ access to and use of Medicare and Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care. 2007;45:214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen AK, O’Brien W, Chen Q, et al. Trends in the purchase of surgical care in the community by the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2017;55:S45–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pew Research Center. Digital gap between rural and nonrural America persists; 2019. Available at: www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/31/digital-gap-between-rural-and-nonrural-america-persists/. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 7.Shreck E, Nehrig N, Schneider JA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a US Department of Veterans Affairs Telemental Health (TMH) program for rural veterans. J Rural Ment Health. 2020;44:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Veterans Affairs. The Veteran population; 2020. Available at: www.va.gov/VETDATA/docs/SurveysAndStudies/VETPOP.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 9.West AN, Charlton ME, Vaughan-Sarrazin M. Dual use of VA and non-VA hospitals by veterans with multiple hospitalizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlton ME, Mengeling MA, Schlichting JA, et al. Veteran use of health care systems in rural states: comparing VA and non‐VA health care use among privately insured veterans under age 65. J Rural Health. 2016;32:407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordasco KM, Mengeling MA, Yano EM, et al. Health and health care access of rural women veterans: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Rural Health. 2016;32:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson T. COVID-19 and Rural America. The Medical Care Blog, Sponsored by the Medical Care Section of the American Public Health Association; April 9, 2020.

- 13.Shura RD, Brearly TW, Tupler LA. Telehealth in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in rural veteran and military beneficiaries. J Rural Health. 2021;37:200–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erwin PC. Despair in the American heartland? A focus on rural health. American Public Health Association; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Yehia BR, Greenstone CL, Hosenfeld CB, et al. The Role of VA Community Care in addressing health and health care disparities. Med Care. 2017;55:S4–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bynum JP, Ross JS. A measure of care coordination? J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:336–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller C, Gurewich D, Garvin L, et al. Veterans Affairs and rural community providers’ perspectives on interorganizational care coordination: a qualitative analysis. J Rural Health. 2021. [In press]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordasco KM, Hynes DM, Mattocks KM, et al. Improving care coordination for veterans within VA and across healthcare systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;34(suppl 1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gellad WF. The Veterans Choice Act and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:153–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, et al. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Kerr EA. Completing the MISSION: a blueprint for helping veterans make the most of new choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1567–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weaver SJ, Che XX, Petersen LA, et al. Unpacking care coordination through a multiteam system lens. Medical care. 2018;56:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D, et al. Health care coordination theoretical frameworks: a systematic scoping review to increase their understanding and use in practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(suppl 1):90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald KM, Singer SJ, Gorin SS, et al. Incorporating theory into practice: reconceptualizing exemplary care coordination initiatives from the US Veterans health delivery system. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattocks KM, Cunningham K, Elwy AR, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of cross-system care coordination from the VA state-of-the-art working group on VA/non-VA care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonard C, Gilmartin H, McCreight M, et al. Operationalizing an implementation framework to disseminate a care coordination program for rural Veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bramer WM, Milic J, Mast F. Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2017;105:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica. 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampman MA, Mueller KJ. Experiences of rural non-VA providers in treating dual care veterans and the development of electronic health information exchange networks between the two systems. J Rural Soc Sci. 2011;26:10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones ML. Application of systematic review methods to qualitative research: practical issues. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Botts N, Pan E, Olinger L, Donahue M, Hsing N. Improved veteran access to care through the Veteran Health Information Exchange (VHIE) retail immunization coordination project. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:321–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kramer BJ, Cote SD, Lee DI, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of VA home-based primary care on American Indian reservations: a qualitative multi-case study. Implement Sci. 2017;12:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks E, Manson SM, Bair B, et al. The diffusion of telehealth in rural American Indian communities: a retrospective survey of key stakeholders. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18:60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cretzmeyer M, Moeckli J, Liu WM. Barriers and facilitators to veterans administration collaboration with community providers: the Lodge project for homeless veterans. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53:698–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, et al. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55:S71–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaglioti A, Cozad A, Wittrock S, et al. Non-VA primary care providers’ perspectives on comanagement for rural veterans. Mil Med. 2014;179:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mattocks KM, Baldor R, Bean-Mayberry B, et al. Factors impacting perceived access to early prenatal care among pregnant veterans enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jasuja G, Ameli O, Miller D, et al. Overdose risk for veterans receiving opioids from multiple sources. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:536–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nayar P, Nguyen AT, Ojha D, et al. Transitions in dual care for veterans: non-federal physician perspectives. J Community Health. 2013;38:225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katon JG, Ma EW, Sayre G, et al. Women veterans’ experiences with Department of Veterans Affairs Maternity Care: current successes and targets for improvement. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28:546–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nayar P, Apenteng B, Yu F, et al. Rural veterans’ perspectives of dual care. J Community Health. 2013;38:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein DM, Pham K, Samy L, et al. The veteran-initiated electronic care coordination: a multisite initiative to promote and evaluate consumer-mediated health information exchange. Telemed J E Health. 2017;23:264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlosser J, Kollisch D, Johnson D, et al. VA-community dual care: veteran and clinician perspectives. J Community Health. 2020;45:795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer BJ, Creekmur B, Cote S, et al. Improving access to noninstitutional long‐term care for American Indian veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi J, Peng Y, Erdem E, Woodbridge P, et al. Communication enhancement and best practices for co-managing dual care rural veteran patients by VA and non-VA providers: a survey study. J Community Health. 2014;39:552–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gittell JH. Coordinating mechanisms in care provider groups: relational coordination as a mediator and input uncertainty as a moderator of performance effects. Manage Sci. 2002;48:1369–1516. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gittell JH, Weiss SJ. Coordination networks within and across organisations: a multilevel framework. J Manag Stud. 2004;41:219–246. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spoont M Greer N Su J, et al. Rural vs. urban ambulatory health care: a systematic review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2011. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.