Numerous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have conclusively demonstrated that long-term anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) can reduce the risk of stroke by approximately 68% per year, with a low annual risk of major hemorrhage (1.3%).1 Despite these impressive results, several studies have shown that the use of warfarin in the “real world” for the prevention of ischemic stroke is suboptimal, with only 15%–44% of patients with atrial fibrillation who had no contraindication to the therapy actually receiving warfarin.2 The reasons for this discrepancy between the RCT evidence and clinical practice patterns are unknown.

To test the hypothesis that physicians may underestimate the benefits and overestimate the risks of anticoagulation therapy, we conducted a survey of all cardiologists (n = 58), neurologists (n = 34) and general internists (n = 130) and a random sample of family physicians (n = 243) within the province of Alberta (first mailing in December 1998 and third mailing in June 1999). The response rate was 49% for family physicians, 73% for specialists and 60% overall.

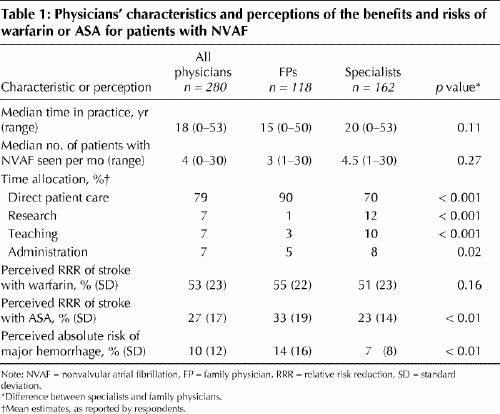

The survey assessed knowledge by presenting a hypothetical patient with NVAF typical of those enrolled in the RCTs. Physicians were then asked to estimate the relative risk reduction (RRR) for stroke (if the patient was taking warfarin or if the patient was taking ASA) and the absolute risk of a major hemorrhage (if the patient was taking warfarin) on a continuum ranging from 0% to 100%, expressed as annual rates.

Respondents underestimated the RRR with warfarin therapy (mean estimate of 53%) compared with that shown in the RCTs (68%) and overestimated the risk of major hemorrhage (10% absolute annual risk v. 1% respectively) (Table 1). In contrast, the mean RRR of ASA was estimated to be higher (27%) than that documented in RCTs (21%).3 Interestingly, family physicians estimated ASA to be significantly more efficacious and the risk of major hemorrhage with warfarin to be significantly higher than the specialists had estimated. Because warfarin therapy is typically monitored by family physicians, these misconceptions may affect a large absolute number of patients.

Table 1

The estimation of a higher risk of hemorrhage with warfarin by family physicians (compared with specialists) has been reported previously.4,5 This may be due to several factors. First, family physicians monitor warfarin therapy on a long-term basis and, therefore, they are more likely to witness adverse outcomes in clinical practice. As such, there may be a natural tendency to remember these sequelae selectively when the therapeutic benefits are intangible (namely, the avoidance of a thromboembolic event). Second, the higher rates of hemorrhage reported by family physicians may reflect the reality of anticoagulant control outside RCTs. Specialists commonly recommend or initiate warfarin therapy based on clinical guidelines and RCTs, or both, but the long-term follow-up is left to the family physician. Patients outside RCTs typically have more concomitant disease and take more drugs, making it more difficult to provide them with appropriate anticoagulation therapy.

Whatever is causing these estimates, it is clear that considerable variability in the evidence for efficacy or hemorrhage with warfarin for patients with NVAF was reported by the survey respondents, as is reflected in the wide standard deviations. This suggests the need for further clinician education and strategies to quantify explicitly individual patients' risks and the potential benefits of warfarin and ASA.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements: At the time of writing, Dr. Bungard was supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Drs. Ghali, Buchan, McAlister and Teo are supported by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Dr. Ghali is also supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair. This study was supported by the University Hospital Foundation (Edmonton) and an unrestricted grant from DuPont Pharmaceuticals.

Competing interests: None declared for Drs. Ghali, McAlister, Cave, Hamilton and Mitchell. Dr. Bungard has received an unrestricted educational grant and honoraria for presentations from DuPont Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Buchan has received speaker fees from Hoffman-La Roche. Dr. Shuaib has been a paid consultant for and has received speaker fees and travel assistance from Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Pfizer and Astra Zeneca. Dr. Teo received speaker fees from DuPont Pharmaceuticals for a lecture on anticoagulation and atrial fibrillation. Dr. Tsuyuki has received several unrestricted travel grants and honoraria for presentations from DuPont Pharmaceuticals.

Correspondence to: Dr. Ross T. Tsuyuki, Director, Epidemiology Coordinating and Research (EPICORE) Centre, Division of Cardiology, 213 Heritage Medical Research Centre, University of Alberta, Edmonton AB T6G 2S2; fax 780 492-6059; ross.tsuyuki@ualberta.ca

References

- 1.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449-57. [PubMed]

- 2.Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, Teo KK, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT. Why do patients with atrial fibrillation not receive warfarin? Arch Intern Med 2000; 160: 41-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. The efficacy of aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation: analysis of pooled data from 3 randomized trials. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1237-40. [PubMed]

- 4.McCrory DC, Matchar DB, Samsa G, Sanders LL, Pritchett ELC. Physician attitudes about anticoagulation for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:277-81. [PubMed]

- 5.Chang HJ, Bell JR, Devoo DB, Kirk JW, Wasson JH. Physician variation in anticoagulating patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:81-4. [PubMed]