Abstract

Background:

Novel subcutaneous (SC) prophylactic therapies are transforming the treatment landscape of hereditary angioedema (HAE). Although questions are being raised about their cost, little attention has been paid to the cost and quality of life (QoL) impact of using on-demand–only medications.

Objective:

We assessed the overall economic burden of on-demand–only treatment for HAE and compared patient QoL with patients who received novel SC prophylactic therapies.

Methods:

US Hereditary Angioedema Association members were invited to complete an anonymous online survey to profile attack frequency, treatment use, and the presence of comorbidities as well as economic and socioeconomic variables. We modeled on-demand treatment costs by using net pricing of medications in 2018, indirect patient and caregiver costs, and attack-related direct billed costs for emergency department admissions, physician office visits, and/or hospitalizations. QoL was assessed by using the Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire.

Results:

A total of 1225 patients (31.4%) responded. Of these, 737 adults with HAE (type I or II) met the inclusion criteria and completed the survey. Per patient/year direct costs associated with modeled on-demand–only treatment totaled $363,795, with additional indirect socioeconomic costs of $52,576 per patient/year. The greatest improvement in QoL was seen in patients who used novel SC prophylactic therapies, with a 59.5% (p < 0.01) improvement in median impairment scores versus on-demand–only treatment. In addition, patients who used novel SC prophylactic therapies reported a 77% reduction in the number of attacks each year when compared with those who used on-demand–only treatment.

Conclusion:

Our real-world patient data showed the cost and QoL burden of HAE treatment with on-demand–only therapy. Use of novel SC prophylaxis can lead to sizeable reductions in attack frequency and statistically significant and clinically relevant improvements in QoL. These data could be useful to clinicians and patients as they consider therapy options for patients with HAE.

Keywords: : hereditary angioedema (HAE), C1inhibitor deficiency, prophylaxis, quality of life (QoL), pharmacoeconomic, health economics, lanadelumab, C1 inhibitor, on-demand treatment, quality of life impairment

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) caused by C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) deficiency is a rare, debilitating, and potentially fatal genetic disorder that affects <8000 people in the United States.1 Two types of HAE are linked to depressed circulating levels of functional C1-INH protein: HAE with low antigenic C1-INH (type I) and HAE with normal antigenic but deficient functional C1-INH (type II).2 Both types of HAE cause severe and unpredictable bouts of cutaneous and mucosal swelling. Cutaneous attacks can affect the extremities, face, trunk, or genitourinary area.3,4 Almost all patients experience abdominal symptoms (pain, nausea, and vomiting) caused by edema in the gastrointestinal mucosa, which may be severe and can be confused with a surgical abdomen. Laryngeal swelling that leads to death by asphyxiation is an omnipresent risk.4 Patients with HAE can experience a deleterious impact on their mental health; in the United States, up to 43% are affected by depression and 15% reported experiencing anxiety.5–7

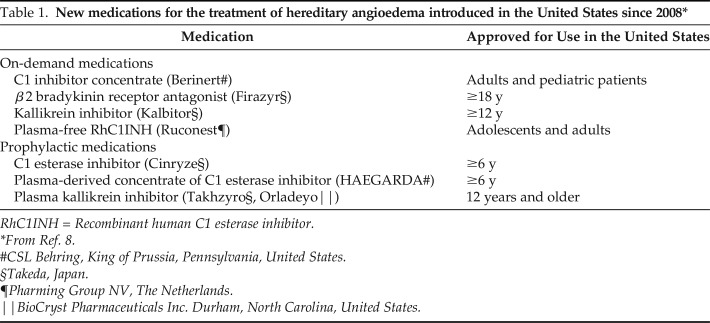

Since 2008, eight medicines have been approved for the treatment of HAE (Table 1).8 These drugs have been approved under the aegis of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Orphan Drug Act,9,10 which provides incentives that make it economically feasible to develop rare disease therapies. FDA approval of two highly effective novel subcutaneous (SC) prophylactic therapies (lanadelumab [Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd, Japan] and human C1-INH (SC) [CSL Behring, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, United States]) offer the potential to transform the HAE treatment landscape and an unprecedented opportunity for a vast majority of patients to lead an attack-free life.11–14 The US Hereditary Angioedema Association (HAEA) Medical Advisory Board 2020 guidelines2 and treatment recommendations note that decisions with regard to the use of long-term prophylactic treatment should not be based on rigid criteria and should reflect individual patient circumstances and needs when taking into account attack frequency and severity, comorbidities, and patient preference. The HAEA Medical Advisory Board further highlighted that the novel therapies' ability to normalize lives by offering improved efficacy, ease of use, and safety is expected to shift the HAE management paradigm toward an expanded adoption of long-term prophylaxis.2

Table 1.

New medications for the treatment of hereditary angioedema introduced in the United States since 2008*

RhC1INH = Recombinant human C1 esterase inhibitor.

From Ref. 8.

#CSL Behring, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, United States.

§Takeda, Japan.

¶Pharming Group NV, The Netherlands.

‖BioCryst Pharmaceuticals Inc. Durham, North Carolina, United States.

The commercial availability of the novel SC HAE therapies has prompted questions about the cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis versus an on-demand–only treatment model,15 yet little attention has been paid to the quality of life (QoL) impact and cost of using the latter approach. Our objective was to use real-world HAE patient data to assess the pharmaco- and socioeconomic burden of an on-demand–only treatment model and compare its impact on attack frequency and QoL impairment with that of prophylaxis, in particular, the novel SC prophylactic therapies.

METHODS

Study Design

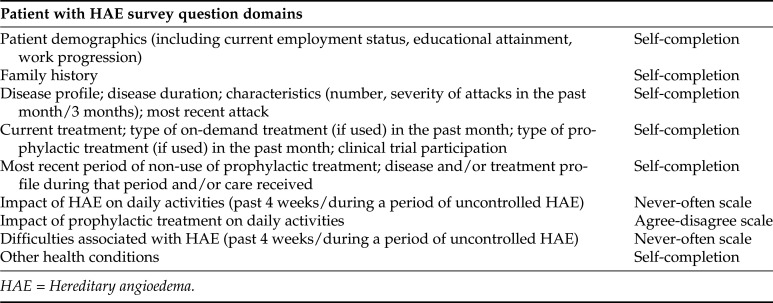

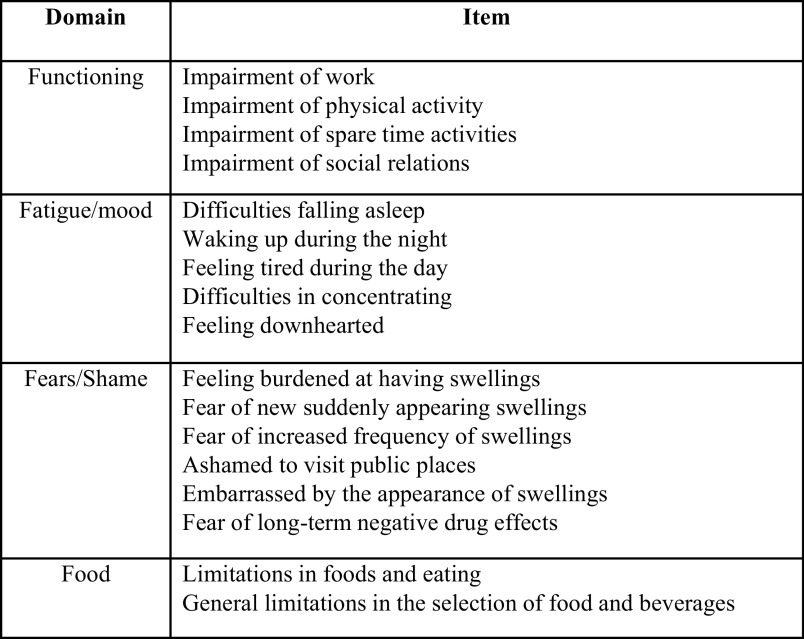

We designed a 103-question online survey instrument to capture real-world patient data on HAE severity, treatments, and comorbidities. Collated economic data included (1) the direct cost for medicines used for treating an attack, emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations, and (2) indirect socioeconomic burden for patients and caregivers. All costs and medical care were directly related to HAE. A summary of the areas covered by the questionnaire is included in Fig. 1. We used the validated Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire (AE-QoL)16 to assess the impact of HAE on QoL (Fig. 2) due to its potential to provide detailed information across multiple domains. When using the AE-QoL, the higher the score, the greater the QoL impairment. We interpreted a six-point change in the AE-QoL as meaningful for a patient with HAE based on the work of Weller et al.17

Figure 1.

Overview of question domains used to collate information about the direct costs and socioeconomic impact of hereditary angioedema (HAE).

Figure 2.

Domains and scoring items adapted from the Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire (AE-QoL) for Patients with Recurrent Swelling Episodes (from Ref. 16).

The HAEA invited patients with HAE to participate in the survey via electronic mail to its membership data base (3904 patients) and social media (the private Facebook Inc, California, United States page of the HAEA membership). A screening question automatically excluded those respondents who had not been formally diagnosed with HAE, were not the diagnosed patient's caregiver, or were < 18 years. Eligible patients signed an online consent form. We did not seek institutional review board approval because the survey was anonymous, and data collected could not be linked to the respondent. Responses were collected in the period from July 9 to 28, 2018.

Study Population

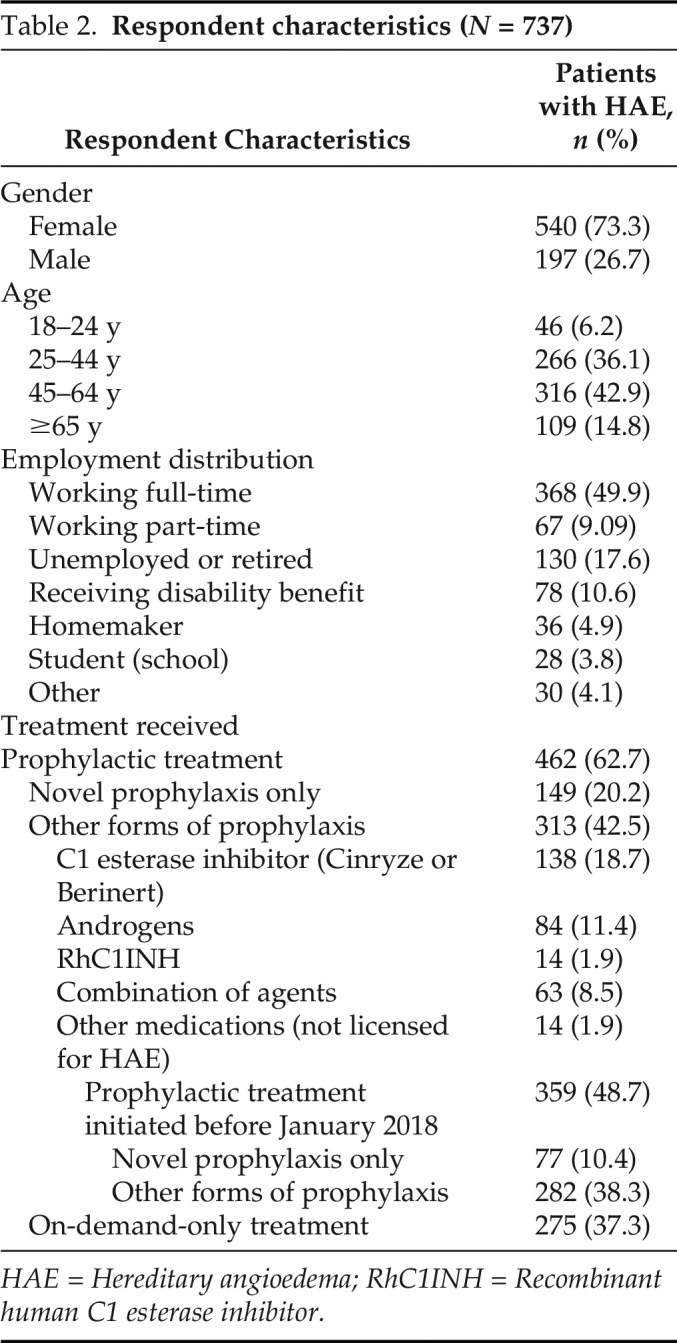

A total of 1225 individuals (31.4%) responded. Of these, a total of 467 respondents were removed due to the following: failure to complete the survey (258), self-identified as having HAE with normal C1-INH (171), or clinically inconsistent and/or incoherent responses (38). The dataset for analysis totaled 758 qualified respondents. Of these, 737 had HAE caused by C1-INH deficiency (Table 2) and 21 respondents were caregivers only, who looked after one or more patients with HAE. Of the 737 patients included in the final analysis, 37.3% (n = 275) were prescribed and using on-demand–only treatment and reported treating 67.2% of their HAE attacks. Of the 62.7% (n = 462) who received prophylactic treatment in addition to having on-demand treatment available, 32.3% (n = 149) received one of the novel SC prophylactic therapies (C1-INH [SC] or lanadelumab). The remaining patients on long-term prophylaxis were receiving C1-INH (29.8%), androgens (18.2%), recombinant human C1 esterase inhibitor (RhC1INH) (3.0%), or a combination of prophylactic agents (13.6%).

Table 2.

Respondent characteristics (N = 737)

HAE = Hereditary angioedema; RhC1INH = Recombinant human C1 esterase inhibitor.

To further explore the real-world situation in which access to medications may not be continuous, we identified patients who were receiving prophylactic treatment and who experienced an interruption in their prophylactic treatment of at least 1 month during the previous year. Of the total prophylactic group, 51.9% (n = 240) reported such an interruption when they either did not have access to or did not use their prophylactic treatment. This population was asked specifically about their HAE attacks and QoL during the most recent full month when they were not taking their prophylactic medication. These responses were analyzed, along with those from the 275 patients in the on-demand–only treatment group in a combined group referred to as the “modeled on-demand–only treatment” group (n = 515) to calculate the direct costs of treatment. When calculating these direct costs, the number of patients who used the specified health care services was based on the proportion of the modeled on-demand–only treatment group who answered the questions. Patients who were using a single, novel SC prophylactic therapy before January 2018 (n = 77) were evaluated in a subgroup analysis. Only those who began therapy before January 2018 were included to ensure that the survey data encompassed a full 6-month treatment period and avoided the run-in period associated with phase III trials.11,12

Statistical Analysis

Parameters are reported as mean ± standard deviation, total U.S. dollars for pharmaco- and socioeconomic costs, and the median score on the AE-QoL instrument. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata, StataCorp, College Station, Texas, United States and Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Washington, United States by Copenhagen Economics. In all cases, a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used Mood's median test to test for statistically significant differences in QoL medians, which is a special case of the Pearson χ2 test. Mood's median test is a nonparametric test with the null hypothesis that the median QoLs of the two populations from which the two samples are drawn are identical.

RESULTS

Direct Costs of On-Demand–Only Treatment

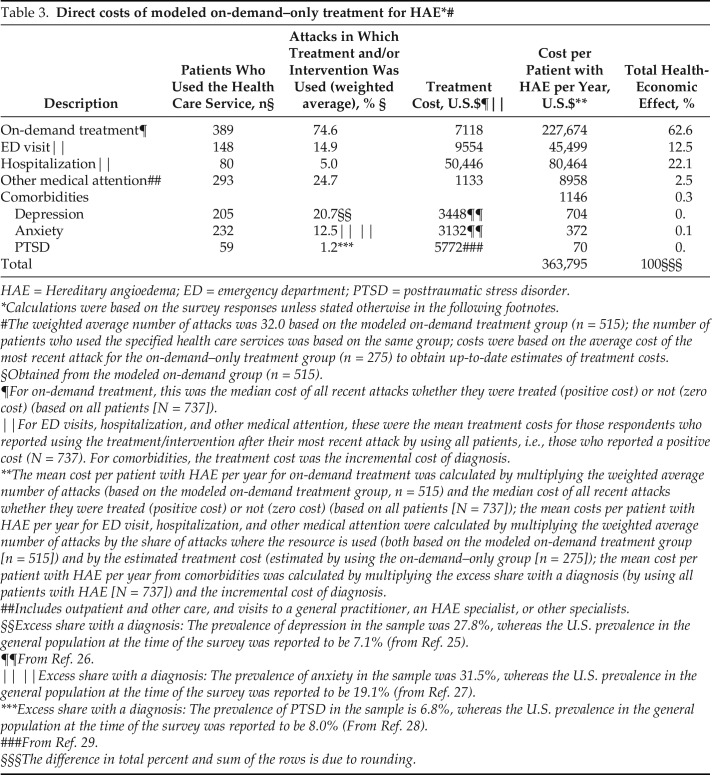

The estimated direct costs of modeled on-demand–only treatment were calculated by using several components (Table 3), specifically, the cost of treating HAE attacks with on-demand medication; the frequency and cost of ED visits, hospitalization, and specialist consultations as a result of HAE attacks; and the incremental incidence and cost of comorbidities, such as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder per patient with HAE per annum. Medications comprise the largest component (62.5%) of modeled on-demand–only treatment, at an estimated $227,674 per patient per year. The median cost of treatment “per attack” was estimated by using self-reported data on the amount and type of medication used to treat the most recent attack and the net pricing of medication in 2018. The second highest component cost was hospitalization for treatment of an HAE attack (22.1%), followed by ED visits (12.5%).

Table 3.

HAE = Hereditary angioedema; ED = emergency department; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Calculations were based on the survey responses unless stated otherwise in the following footnotes.

The weighted average number of attacks was 32.0 based on the modeled on-demand treatment group (n = 515); the number of patients who used the specified health care services was based on the same group; costs were based on the average cost of the most recent attack for the on-demand–only treatment group (n = 275) to obtain up-to-date estimates of treatment costs.

§Obtained from the modeled on-demand group (n = 515).

¶For on-demand treatment, this was the median cost of all recent attacks whether they were treated (positive cost) or not (zero cost) (based on all patients [N = 737]).

‖For ED visits, hospitalization, and other medical attention, these were the mean treatment costs for those respondents who reported using the treatment/intervention after their most recent attack by using all patients, i.e., those who reported a positive cost (N = 737). For comorbidities, the treatment cost was the incremental cost of diagnosis.

**The mean cost per patient with HAE per year for on-demand treatment was calculated by multiplying the weighted average number of attacks (based on the modeled on-demand treatment group, n = 515) and the median cost of all recent attacks whether they were treated (positive cost) or not (zero cost) (based on all patients [N = 737]); the mean costs per patient with HAE per year for ED visit, hospitalization, and other medical attention were calculated by multiplying the weighted average number of attacks by the share of attacks where the resource is used (both based on the modeled on-demand treatment group [n = 515]) and by the estimated treatment cost (estimated by using the on-demand–only group [n = 275]); the mean cost per patient with HAE per year from comorbidities was calculated by multiplying the excess share with a diagnosis (by using all patients with HAE [N = 737]) and the incremental cost of diagnosis.

##Includes outpatient and other care, and visits to a general practitioner, an HAE specialist, or other specialists.

§§Excess share with a diagnosis: The prevalence of depression in the sample was 27.8%, whereas the U.S. prevalence in the general population at the time of the survey was reported to be 7.1% (from Ref. 25).

¶¶From Ref. 26.

‖ ‖Excess share with a diagnosis: The prevalence of anxiety in the sample was 31.5%, whereas the U.S. prevalence in the general population at the time of the survey was reported to be 19.1% (from Ref. 27).

***Excess share with a diagnosis: The prevalence of PTSD in the sample is 6.8%, whereas the U.S. prevalence in the general population at the time of the survey was reported to be 8.0% (From Ref. 28).

###From Ref. 29.

§§§The difference in total percent and sum of the rows is due to rounding.

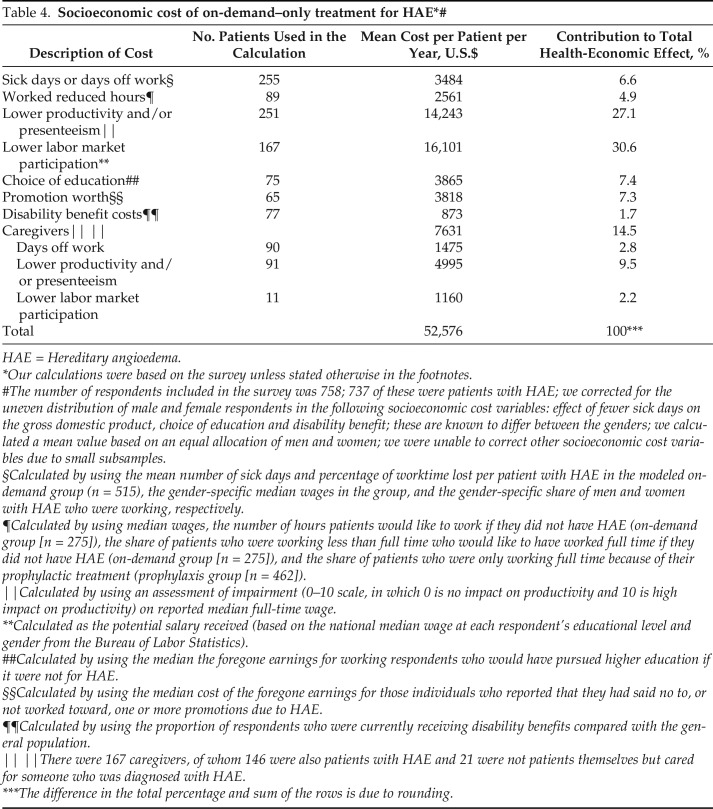

Socioeconomic Costs of On-Demand–Only Treatment

The estimated socioeconomic costs of patients by using modeled on-demand–only treatment are summarized in Table 4. Survey respondents reported that HAE had a substantial impact on their ability to work and their productivity when at work. When asked to estimate what they would achieve if they did not have HAE, increased labor market participation and improvements in productivity14 accounted for more than half (57.7%) of the indirect costs ($30,344). The possibility of greater educational attainment (choice of education) and career advancement (promotion worth) in the absence of HAE represented 14.7% of the potential socioeconomic costs ($7683). Sick days due to HAE and the need to work reduced hours because of HAE were estimated to cost $6045 per patient per year and accounted for 11.5% of all socioeconomic costs. For those respondents who indicated that they were either patients or caregivers or solely caregivers, the fact that they would no longer have to take time off work or could participate in the labor force, or be more productive while at work, accounted for $7630 (14.5%).

Table 4.

HAE = Hereditary angioedema.

Our calculations were based on the survey unless stated otherwise in the footnotes.

The number of respondents included in the survey was 758; 737 of these were patients with HAE; we corrected for the uneven distribution of male and female respondents in the following socioeconomic cost variables: effect of fewer sick days on the gross domestic product, choice of education and disability benefit; these are known to differ between the genders; we calculated a mean value based on an equal allocation of men and women; we were unable to correct other socioeconomic cost variables due to small subsamples.

§Calculated by using the mean number of sick days and percentage of worktime lost per patient with HAE in the modeled on-demand group (n = 515), the gender-specific median wages in the group, and the gender-specific share of men and women with HAE who were working, respectively.

¶Calculated by using median wages, the number of hours patients would like to work if they did not have HAE (on-demand group [n = 275]), the share of patients who were working less than full time who would like to have worked full time if they did not have HAE (on-demand group [n = 275]), and the share of patients who were only working full time because of their prophylactic treatment (prophylaxis group [n = 462]).

‖Calculated by using an assessment of impairment (0–10 scale, in which 0 is no impact on productivity and 10 is high impact on productivity) on reported median full-time wage.

**Calculated as the potential salary received (based on the national median wage at each respondent's educational level and gender from the Bureau of Labor Statistics).

##Calculated by using the median the foregone earnings for working respondents who would have pursued higher education if it were not for HAE.

§§Calculated by using the median cost of the foregone earnings for those individuals who reported that they had said no to, or not worked toward, one or more promotions due to HAE.

¶¶Calculated by using the proportion of respondents who were currently receiving disability benefits compared with the general population.

‖ ‖There were 167 caregivers, of whom 146 were also patients with HAE and 21 were not patients themselves but cared for someone who was diagnosed with HAE.

***The difference in the total percentage and sum of the rows is due to rounding.

Impact of Treatment on Attack Frequency

Attack frequency differed according to the type of treatment. In the 12 months immediately before survey completion, the mean ± standard deviation number of attacks per year for those who received the novel SC prophylactic therapies (n = 77) was 5.92 ± 12.25 compared with 16.60 ± 23.88 for patients who used other forms of prophylaxis (n = 282) and 26.27 ± 29.56 for those patients who used on-demand–only treatment (n = 275). The proportion of patients who reported zero attacks in the 3 months immediately before completing the survey also differed according to treatment type. Only 19% of the patients who used on-demand–only treatment (n = 275) experienced no attacks during this treatment interval compared with 57% of patients who received the novel SC prophylactic therapies (n = 77) and 26% of patients on other forms of prophylaxis (n = 282).

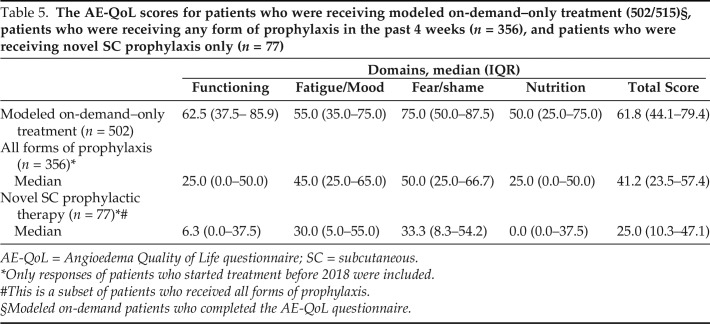

Impact of Treatment and Attack Frequency on QoL

In Table 5 we show the impact of treatment on AE-QoL impairment scores. The use of any prophylactic medication led to a clinically meaningful 33.3% improvement in the overall median (interquartile range) QoL impairment score when compared with modeled on-demand-only treatment (41.2 [23.5–57.4] versus 61.8 [44.1–79.4]; p < 0.01). Subgroup analysis of patients who used the novel SC prophylactic treatments (n = 77) showed a substantially greater improvement (59.5%) in overall median (interquartile range) AE-QoL impairment score when compared with the use of modeled on-demand–only treatment (25.0 [10.3–47.1] versus 61.8 [44.1–79.4]; p < 0.01). Improvements in median AE-QoL impairment scores were statistically significant across all QoL domains (p < 0.01).

Table 5.

The AE-QoL scores for patients who were receiving modeled on-demand–only treatment (502/515)§, patients who were receiving any form of prophylaxis in the past 4 weeks (n = 356), and patients who were receiving novel SC prophylaxis only (n = 77)

AE-QoL = Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire; SC = subcutaneous.

*Only responses of patients who started treatment before 2018 were included.

#This is a subset of patients who received all forms of prophylaxis.

Modeled on-demand patients who completed the AE-QoL questionnaire.

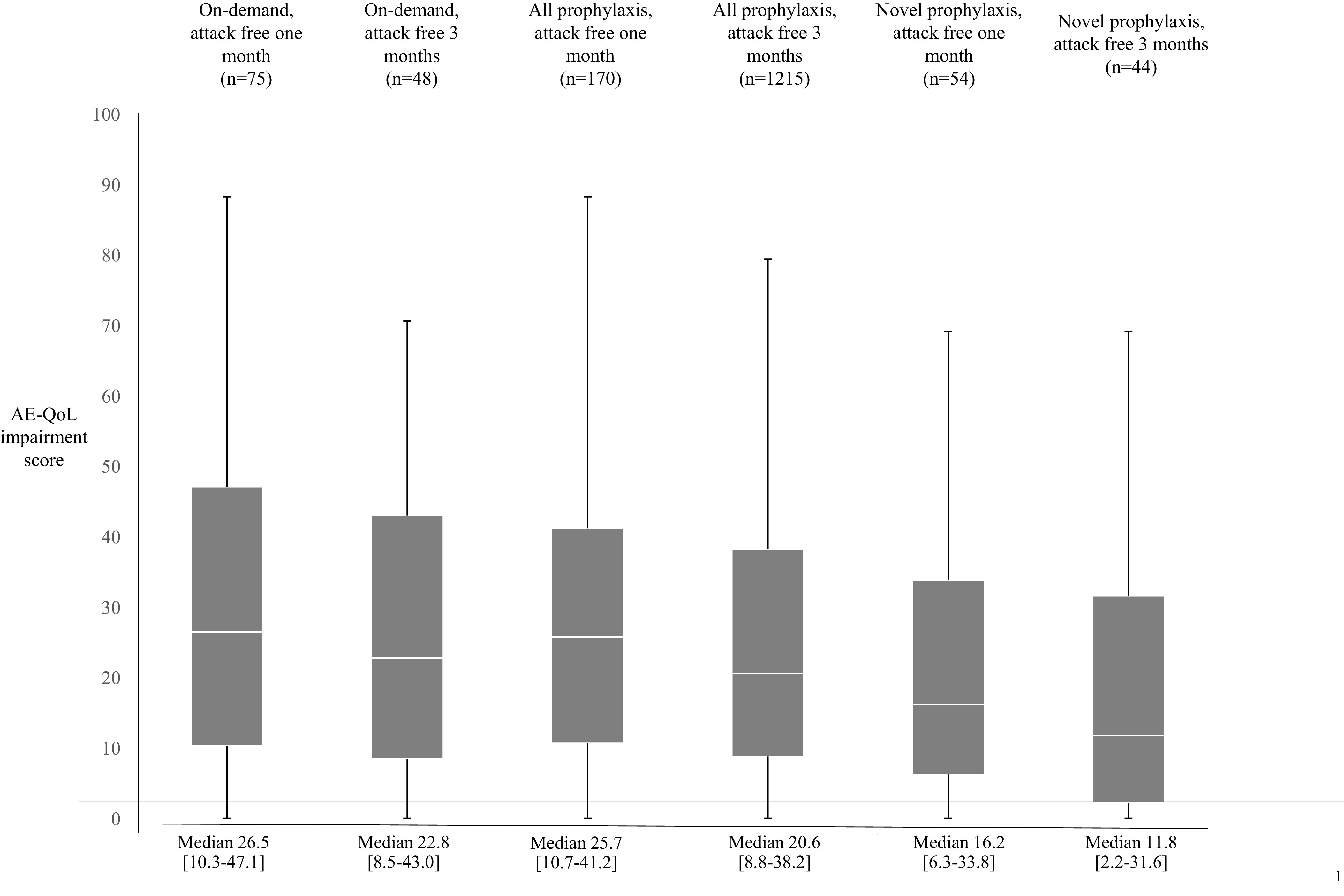

The impacts of being attack-free on QoL are shown in Fig. 3. The respondents who reported zero attacks in the month before survey completion reported clinically meaningful, statistically significant improvements (ranging from 32.8% to 57.1%) in QoL for all patients when compared with overall QoL scores for each group (Table 5). When looking at the impact of being attack-free for 3 months before survey completion, further statistically significant improvements (ranging from 14.0% to 29.8%) were seen across all patients. Significantly greater and clinically meaningful improvements in overall QoL scores were observed in patients who took novel SC prophylactic therapies compared with those who used on-demand–only treatment and any form of prophylaxis (11.8 [2.2–31.6] versus 22.8 [8.8–43.0] versus 20.6 [8.5–43.0]; p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Angioedema Quality of Life questionnaire (AE-QoL) scores in the most recent 4 weeks (total domain score, AE-QoL score (median value and the interquartile range ([IQR]) according to attack frequency and treatment model).

DISCUSSION

Our study focused on modeling the overall economic burden of on-demand–only treatment and comparing QoL with patients who received novel SC prophylactic therapies for HAE by using real-world patient-provided data. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) reviewed the effectiveness and value of HAE prophylaxis in a November 2018 report.15 ICER concluded that prophylactic treatment for HAE C1-INH deficiency did not meet traditional cost-effectiveness thresholds and based its conclusions on estimated costs of novel SC therapies, which ranged from $377,786 to $423,344.15 Although differences in objectives and methodologies preclude a direct comparison with the ICER study,15 our real-world data provided a value context for the novel SC therapies. Modeled on-demand–only treatment costs of $363,795 and socioeconomic costs of $52,576, coupled with the dramatic increase in QoL and decrease in attack frequency reported by patients on novel SC therapies, provided a benchmark for clinicians and patients as they consider novel SC prophylaxis medications in the context of applying treatment guidelines.

Our 737-patient cohort represented almost 20% of the HAEA members and, to our knowledge, was the largest ever number of respondents to be included in an HAE survey. The survey also showed that treatment modality, attack frequency, and QoL impairment were closely linked. Prophylaxis yields a significant reduction in the number of attacks and meaningful improvements in QoL when compared with the current use of on-demand–only treatment. As patients move closer to an attack-free life, they experience clinically relevant and statistically significant improvements in QoL. Importantly, it showed that the novel SC prophylactic treatments offered the prospect of an attack-free life for many patients.

Our findings were consistent with those of recent clinical trials that show prophylaxis with the novel SC therapies leads to significant reductions in attack frequency and clinically relevant improvements in QoL.12–14,18 The availability of real-world comparative data with regard to QoL impairment in patients with HAE is limited. In a small sample of patients with HAE included in the validation process for the AE-QoL tool used in this survey, Weller et al.16 showed an overall median impairment score of ∼39.0 points. Because we focused on examining differences in a variety of patient subgroups (Table 5) our analysis showed a broad range of median impairment, from 11.8 to 61.8 points. As noted earlier, Weller et al.17 identified a six-point change in the AE-QoL as the minimal clinically important difference to indicate a meaningful change to a patient. Our survey showed that use of prophylactic therapies led to improvements in AE-QoL scores that were three to six times greater than the minimal clinically important difference by Weller et al.17 when compared with modeled on-demand–only treatment. Similar clinically meaningful improvements in QoL, up to sixfold, were seen across all treatment approaches when looking at the attack-free status.

Our overall findings supported the conclusions of the analysis of health-related QoL data from the Clinical Study for Optimal Management of Preventing Angioedema with Low-Volume Subcutaneous C1-Inhibitor Replacement Therapy (COMPACT) study, a clinical trial that evaluated self-administered C1-INH (SC) as routine prophylaxis.14 The investigators reported that self-administered prophylactic treatment with C1-INH (SC) had a greater impact on improving multiple dimensions of HAE-related QoL impairment, most notably anxiety and work productivity, when compared with on-demand–only treatment. In the Hereditary Angioedema Long-Term Prophylaxis (HELP) study,13 which evaluated three different prophylactic lanadelumab regimens (150 or 300 mg every 4 weeks or 300 mg every 2 weeks), patients experienced a clinically relevant and statistically significant improvement in QoL total scores over 26 weeks in all three treatment groups when compared with placebo.13

The survey results provided a real-world perspective on the findings of published clinical trials in terms of frequency of attacks. Our survey showed that up to 57% of patients with HAE experienced no attacks in the 12 weeks immediately before survey completion when receiving the novel SC prophylactic treatments for at least 6 months. Clinical studies show that between 40% and 44% of patients on SC HAE prophylactic medications experience zero attacks during treatment periods that ranged from 4 to 26 weeks.11–13 More recent data from the C1-INH (SC) (human) phase III open label trial18 and a post hoc analysis performed as part of the lanadelumab clinical trial13 indicate that well over 80% of patients achieve a sustained period of no attacks. Clinical trial data also reveal that a 99% reduction in the use of rescue medication is possible.12 When looking at the data gathered in the process of modeling the health economic implications of on-demand–only treatment for HAE, our real-world findings reflected those of other published studies. For example, our finding that 67% of attacks were treated mirrors the 72% reported by Banerji et al.19 in a survey of 143 patients conducted at the 2015 HAEA conference.

The only other study that solely addressed the economic costs associated with acute HAE attacks showed an average annual per-patient total cost of $42,000, which comprised direct and indirect costs of $26,000 and $16,000, respectively.20 These figures are substantially lower than the average direct annual cost of $363,795 reported in our study. Several components may contribute to this difference. First, during the survey period covered by the study by Wilson et al.20 (November 2007 through January 2008), there were no approved treatments for acute attacks in the United States. Most patients used nonspecific treatments (androgens [36.3%], antihistamines [19.7%], or pain medicine and/or narcotics [31.5%]), which resulted in an average medication cost of $284 per patient per year.20 In our study, on-demand treatment costs with effective FDA-approved on-demand medicine totaled $227,674 per patient per year and accounted for 63% of the direct costs. Second, our ED and hospitalization costs were reported from the actual bills received by patients in 2018 rather than standard unit costs based on U.S. treatment codes in 2007. Third, our economic model included comorbidities and the socioeconomic cost model incorporated several variables that were not included in the Wilson et al.20 study, including lower productivity, missed educational and promotion opportunities, disability benefit costs, and caregiver costs.

Our survey had many strengths. It provided a real-world model based on charges to patients with HAE and their insurance companies, and revealed the high direct medical and socioeconomic costs of the on-demand–only treatment model. It also showed that some patients who used the on-demand–only treatment model experienced significant QoL impairment. In stratifying the impact of different types of prophylactic treatment on QoL and, most importantly, the effect of the novel SC therapies on attack frequency and QoL, we showed that the novel SC prophylactic treatments improved attack frequency and QoL without adding substantially to health care costs. The survey population was a nonrandom sample of patients who were self-selected by their willingness to answer an online questionnaire and could be subject to several biases, including recall and social desirability.21–23 Even though HAE has a similar prevalence in men and women, as in most surveys of patients with HAE, women were overrepresented in our sample. This reflects a generally observed phenomenon that women are more inclined to answer surveys than men.23

The use of self-reported data is an important element of health care utilization assessment. Data with regard to the frequency and severity of attacks and treatment outcomes rely on a patient accurately recalling details of the experience.24 Although we collected information on treatments used to treat HAE attacks, and all were licensed for self-injection, information with regard to whether injections were self-administered was not available. Also, we calculated attack frequency by annualizing attacks reported for 1 month. This approach assumed that attacks have a predictable pattern, but we know that the frequency of HAE attacks can vary over time.2,14 Despite these limitations, we believe that the large number of respondents was a strength that supported the accuracy of our data set.

CONCLUSION

Our real-world patient data revealed that modeled on-demand–only therapy had high treatment and socioeconomic costs, and was associated with high levels of QoL impairment. Novel SC therapies offer a statistically significant reduction in attack frequency and QoL impairment, with post hoc clinical trial data that showed that a majority of patients became attack-free. Analysis of these data provided a perspective on value that can inform clinician and patient decision-making on a suitable therapeutic approach.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the patients with HAE and caregivers who participated in the survey, Lynn Hamilton for editorial support, and Janet F. Long for help in survey design and testing.

Footnotes

This survey was funded by the US Hereditary Angioedema Association and Hereditary Angioedema International. Both organizations receive financial support from a variety of sources that include its members and the general public. The US Hereditary Angioedema Association and Hereditary Angioedema International also accept grants from BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc., CSL Behring, Pharming Group N.V., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited for disease education and awareness activities. None of the companies cited above nor anyone other than the authors had any involvement in the study's initiation, design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit it for publication.

B.L. Zuraw has a patent submitted by both himself and his institution; received royalties from UpToDate; and received consultant fees from Shire/Takeda, CSL Behring, Biocryst, Adverum, Alynylam, Arrowhead, Attune, Kalvista, and Nektar; his institution has received grants from the US Hereditary Angioedema Association. S.C. Christiansen has received consultancy fees from CSL Behring, Shire/Takeda, and BioCryst. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lumry WR. Pharmacoeconomics of orphan disease treatment with a focus on hereditary angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017; 37:617–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC, Riedl MA, et al. US HAEA Medical Advisory Board 2020 Guidelines for the Management of Hereditary Angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021; 9:132–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. How we manage persons with hereditary angioedema. Br J Haematol. 2016; 173:831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banerji A, Busse P, Christiansen SC, et al. Current state of hereditary angioedema management: a patient survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015; 36:213–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caballero T, Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, et al. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: results from the burden of illness study in Europe. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014; 35:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bygum A, Aygören-Pürsün E, Beusterien K, et al. Burden of illness in hereditary angioedema: a conceptual model. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015; 95:706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Longhurst H, Bygum A. The humanistic, societal, and pharmaco-economic burden of angioedema. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2016; 51:230–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Hereditary Angioedema Association. FDA approved treatments. Available online at https://www.haea.org/pages/p/ApprovedTreatments; accessed 22 December 2020.

- 9. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Orphan Drug Act of 1983. Pub. L. 97–414, 96 Stat 2049 (1983).

- 10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Amendments of 1984. Pub. L. 98–551, 98 Stat 2815 §4 (1984).

- 11. Zuraw BL, Cicardi M, Longhurst HJ, et al. Phase II study results of a replacement therapy for hereditary angioedema with subcutaneous C1inhibitor concentrate. Allergy. 2015; 70:1319–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Longhurst H, Cicardi M, Craig T, et al. Prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks with a subcutaneous C1 inhibitor. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:1131–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Banerji A, Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, et al. Effect of lanadelumab compared with placebo on prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018; 320:2108–2121. 10.1001/jama.2018.16773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lumry WR, Craig T, Zuraw B, et al. Health-related quality of life with subcutaneous C1 inhibitor for prevention of attacks of hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018; 6:1733–1741.e3. Epub 2018 Jan 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Final Report on Long-Term Prophylaxis for Hereditary Angioedema, Provides Policy Recommendations to Improve Cost-Effectiveness. 2018. Available online at https://icer-review.org/announcements/institute-for-clinical-and-economic-review-issues-final-report-on-long-term-prophylaxis-for-hereditary-angioedema-provides-policy-recommendations-to-improve-cost-effectiveness/; accessed 15 November 2018.

- 16. Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012; 67:1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling-Oberhag A, et al. The Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL) – assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016; 71:1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Craig T, Zuraw B, Longhurst H, et al. Long-term outcomes with subcutaneous c1inhibitor replacement therapy for prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019; 7:1793–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Banerji A, Li Y, Busse P, et al. Hereditary angioedema from the patient’s perspective: a follow-up patient survey. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018; 39:212–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson DA, Bork K, Shea EP, et al. Economic costs associated with acute attacks and long-term management of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010; 104:314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bethlehem J. Selection bias in web surveys. Int Stat Rev. 2010; 78:161–188. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definitions, pitfalls; and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016; 9:211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore DL, Tarnai J. Evaluating nonresponse error in mail surveys. In: Groves RM, Dillman DA, Eltinge JL, et al. (Eds.). Survey Nonresponse. New York: John Wiley; 2002: 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kwong E, Black N. Retrospectively patient-reported pre-event health status showed strong association and agreement with contemporaneous reports. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017; 81:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression. Available online at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml; accessed September 11, 2020.

- 26. Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015; 76:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Institute of Mental Health. Any anxiety disorder. Available online at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/any-anxiety-disorder.shtml; accessed September 8, 2020.

- 28. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Epidemiology of PTSD. Available online at https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/coe/cihvisn2/Documents/Provider_Education_Handouts/Epidemiology_of_PTSD_Version_3.pd; accessed September 8, 2020.