Abstract

Background

Value-based healthcare models aim to incentivize healthcare providers to offer interventions that address determinants of health. Understanding patient priorities for physical and socioeconomic recovery after injury can help determine which services and resources are most useful to patients.

Questions/purposes

(1) Do trauma patients consistently identify a specific aspect/domain of recovery as being most important at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after an injury? (2) Does the relative importance of those domains change within the first year after injury? (3) Are differences in priorities greater between patients than for a given patient over time? (4) Are different recovery priorities associated with identifiable biopsychosocial factors?

Methods

Between June 2018 and December 2018, 504 adult patients with fractures of the extremities or pelvis were surgically treated at the study site. For this prospective longitudinal study, we purposefully sampled patients from 6 of the 12 orthopaedic attendings’ postoperative clinics. The participating surgeons surgically treated 243 adult patients with fractures of the extremities or pelvis. Five percent (11 of 243) of patients met inclusion criteria but missed their appointments during the 6-week recruitment window and could not be consented. We excluded 4% (9 of 243) of patients with a traumatic brain injury, 1% (2) of patients with a spinal cord injury, and 5% (12) of non-English-speaking patients (4% Spanish speaking [10]; 1% other languages [2]). Eighty-six percent of eligible patients (209 of 243) were approached for consent, and 5% (11 of 209) of those patients refused to participate. All remaining 198 patients consented and completed the baseline survey; 83% (164 of 198 patients) completed at least 6 months of follow-up, and 68% (134 of 198 patients) completed the 12-month assessment. The study participants’ mean age was 44 ± 17 years, and 63% (125 of 198) were men. The primary outcome was the patient’s recovery priorities, assessed at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after fracture using a discrete choice experiment. Discrete choice experiments are a well-established method for eliciting decisional preferences. In this technique, respondents are presented with a series of hypothetical scenarios, described by a set of plausible attributes or outcomes, and asked to select their preferred scenario. We used hierarchical Bayesian modeling to calculate individual-level estimates of the relative importance of physical recovery, work-related recovery, and disability benefits, based on the discrete choice experiment responses. The hierarchical Bayesian model improves upon more commonly used regression techniques by accounting for the observed response patterns of individual patients and the sequence of scenarios presented in the discrete choice experiment when calculating the model estimates. We computed the coefficient of variation for the three recovery domains and compared the between-patient versus within-patient differences using asymptotic tests. Separate prognostic models were fit for each of the study’s three recovery domains to assess marginal changes in the importance of the recovery domain based on patient characteristics and factors that remained constant over the study (such as sex or preinjury work status) and patient characteristics and factors that varied over the study (including current work status or patient-reported health status). We previously published the 6-week results. This paper expands upon the prior publication to evaluate longitudinal changes in patient recovery priorities.

Results

Physical recovery was the respondents’ main priority at all three timepoints, representing 60% ± 9% of their overall concern. Work-related recovery and access to disability benefits were of secondary importance and were associated with 27% ± 6% and 13% ± 7% of the patients’ concern, respectively. The patients’ concern for physical recovery was 6% (95% CrI 4% to 7%) higher at 12 months after fracture that at 6 weeks postfracture. The mean concern for work-related recovery increased by 7% (95% CrI 6% to 8%) from 6 weeks to 6 months after injury. The mean importance of disability benefits increased by 2% (95% CrI 1% to 4%) from 6 weeks to 6 months and remained 2% higher (95% CrI 0% to 3%) at 12 months after the injury. Differences in priorities were greater within a given patient over time than between patients as measured using the coefficient of variation (physical recovery [245% versus 7%; p < 0.001], work-related recovery [678% versus 12%; p < 0.001], and disability benefits [620% versus 33%; p < 0.001]. There was limited evidence that biopsychosocial factors were associated with variation in recovery priorities. Patients’ concern for physical recovery was 2% higher for every 10-point increase in their Patient-reported Outcome Measure Information System (PROMIS) physical health status score (95% CrI 1% to 3%). A 10-point increase in the patient’s PROMIS mental health status score was associated with a 1% increase in concern for work-related recovery (95% CrI 0% to 2%).

Conclusion

Work-related recovery and accessing disability benefits were a secondary concern compared with physical recovery in the 12 months after injury for patients with fractures. However, the importance of work-related recovery was elevated after the subacute phase. Priorities were highly variable within a given patient in the year after injury compared with between-patient differences. Given this variation, orthopaedic surgeons should consider assessing and reassessing the socioeconomic well-being of their patients throughout their continuum of care.

Level of Evidence

Level II, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Fractures are associated with physical and socioeconomic impairment, which may be temporary or permanent [2, 7, 22]. This loss of function may result in loss of ability to work, earn an income, or other disruptions to activities of daily living [15, 20, 23, 28]. Clinicians, such as orthopaedic surgeons, focus on physiologic and biologic healing of fractures and emphasize the patient’s physical recovery. However, other aspects of recovery, such as return to work and financial security, are often not addressed with such focus [9, 11, 12, 27].

The economic distress experienced by patients after trauma has been well documented [2, 20, 22]. Consequently, all US states administer some form of workers compensation, and many employers augment this insurance with sick leave programs or unpaid job protection under the Family and Medical Leave Act [3]. Previous work has demonstrated that social interventions, such as assistance in finding and retaining employment, peer support programs, and stable housing support, can reduce hospital readmissions [1, 12]. However, the availability of social interventions in the clinical environment and access to social welfare vary substantially across health systems and jurisdictions in the United States [18]. In addition, perverse incentives often exist, where highly compensated services are often more readily available than less lucrative but potentially more effective interventions [5, 18]. Without knowing what patients value most over their continuum of care, the appropriate allocation of services and resources is impossible and efficacious programs will be underutilized.

We, therefore, asked the following in a group of patients who had fracture surgery: (1) Do trauma patients consistently identify a specific aspect/domain of recovery as being most important at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after injury? (2) Does the relative importance of those domains change within the first year of injury? (3) Are differences in priorities greater between patients than for a given patient over time? (4) Are different recovery priorities associated with identifiable biopsychosocial factors?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

In this prospective study, we assessed patient recovery priorities at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after fracture. Patient recovery priorities were measured using a discrete choice experiment, a technique pioneered by McFadden in 1974 for which he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2000 [17]. Discrete choice experiments are a powerful analytic method used to estimate the probability of individuals making a particular choice from presented alternatives. The technique has served as a valuable tool for designing health policies and health services, such as Medicare Part D [10]. All patients were recruited for participation between June 2018 and December 2018 from a single Level 1 trauma center in Maryland. The 6-week survey data reported in this study have been previously published [21]. The prior publication was considered pilot and feasibility work. The questions posed within this paper were unanswerable with initial data from a single timepoint and required the repeated measures of this longitudinal study. The University of Maryland’s institutional review board approved the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study Participants

Between June 2018 and December 2018, 504 patients with fractures of the extremities or pelvis underwent surgery at the study site (Fig. 1). Given our limited research staff, we purposefully sampled patients from 6 of the 12 orthopaedic attendings’ postoperative clinics. Under this restriction, 243 patients met the inclusion criteria. Five percent (11 of 243) of patients met the inclusion criteria but missed their clinical appointments during the 6-week recruitment window and could not be consented. We excluded 4% (9 of 243) of patients with a traumatic brain injury, 1% (2) of patients with a spinal cord injury, and 5% (12) of non-English-speaking patients (4% [10] Spanish speaking; 1% [2] other languages). All patients were enrolled after their surgical treatment but within 6 weeks of their fracture and were provided with a USD 20 gift card for each completed study assessment. Of the 209 patients who met the eligibility criteria, 198 patients consented and completed the baseline survey, 83% (164 of 198 patients) completed at least 6 months of follow-up, and 68% (134 of 198 patients) completed the 12-month assessment. One-hundred thirty of 198 patients (66%) completed all three surveys. One patient (1%) consented and completed the baseline assessment but died before completing the 6-month survey. The mean age of the respondents was 44 ± 17 years, 63% (125 of 198) were men, and 37% (74 of 198) were of a racial minority (Table 1). Sixty-nine percent (137 of 198) of the patients were employed at the time of injury, and the median annual household income was USD 35,000 (IQR USD 15,000 to USD 57,500). Seventy-five percent (149 of 198) of the respondents had a lower extremity fracture, 9% (18 of 198) of the patients had fractures in more than one anatomical region, and 31% (61 of 198) of the fractures were open. The patients who failed to complete 12 months of follow-up differed from patients who completed 12 months of follow-up in three measured characteristics (Appendix Table 1; Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A482). Patients who were lost to follow-up differed in their health insurance coverage, most notably in the proportion who were uninsured (22% versus 9%; p = 0.03). Male patients were also less likely to complete the 12-month assessment (75% versus 58%; p = 0.02). Foot and ankle fracture patients were more likely to complete the 12 months of follow-up (31% versus 17%; p = 0.05). Twenty percent (40 of 198 patients) had a reoperation or readmission within 1 year of injury (Table 2). Of those patients, the median time to the first reoperation or readmission was 150 days (IQR 72 to 233 days). Three percent (5 of 198 patients) had more than one complication. The most common medical complications were a deep surgical site infection (7% [13 of 198]) and symptomatic hardware removal (6% [12 of 198]). Sixty-five percent (71 of 110) of patients who were working before their injury resumed working in the year after their injury (Table 3). These patients were absent from work for a median of 7 months (IQR 5 to 11). Of those who returned to work, 76% (54 of 71) returned to the same employer, 69% (49 of 71) returned to the same or higher income, and 68% (48 of 71) returned to the same duties. At 12 months after injury, 25% (41 of 164) of the patients were unable to work because of their injury, 16% (27 of 164) were searching for employment, and 5% (9 of 164) were on sick leave. Eighteen percent (29 of 164) of the patients received some form of disability compensation. Forty-five percent (74 of 164) of the sample reported accumulating debt because of their injury. The median debt accumulated was USD 6000 and ranged from USD 640 to USD 130,000.

Fig. 1.

Diagram depicting the patients included in the study, reasons for exclusion, and follow-up at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after injury.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and associated factors

| Patient characteristics and factors | All patients (n = 198) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 43.8 ± 16.7 |

| Men, % (n) | 63 (125) |

| Racial minority, % (n) | 37 (74) |

| Education level, % (n) | |

| High school or less | 47 (94) |

| Some college or associate degree | 25 (50) |

| Bachelor or graduate degree | 27 (54) |

| Dependents, yes, % (n) | 36 (71) |

| Working before injury, % (n) | 69 (137) |

| Employment involving physical labor, % (n) | 18 (36) |

| Annual household income in USD, median (IQR) | 35,000 (15,000-57,500) |

| Area Deprivation Index, median (IQR) | 28 (17-46) |

| Health insurance, % (n) | |

| Private (employer-based, direct purchase) | 42 (83) |

| Public (Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare) | 45 (89) |

| Uninsured | 13 (26) |

| Fracture location, % (n)a | |

| Foot or ankle | 26 (52) |

| Tibia or femur | 49 (97) |

| Pelvis or acetabulum | 11 (22) |

| Upper extremity | 23 (46) |

| Open fracture, % (n) | 31 (61) |

| Preinjury PROMIS physical status, median (IQR) | 50.3 (42.9-56.0) |

| Preinjury PROMIS mental status, median (IQR) | 52.7 (47.7-58.2) |

19 patients had fractures in more than one anatomical region; PROMIS = Patient-reported Outcome Measurement Information System.

Table 2.

Major medical complications resulting in readmission or reoperation (n = 198)

| Complication | % (n) | Median time to complication in days (IQR) |

| All complicationsa | 20 (40) | 150 (72-233) |

| Deep surgical site infection | 7 (13) | 146 (33-195) |

| Symptomatic hardware removal | 6 (12) | 235 (146-362) |

| Nonunion | 5 (10) | 148 (83-244) |

| Amputation | 2 (3) | 83 (4-84) |

| Conversion to arthroplasty | 2 (3) | 151 (34-215) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (1) | 70 |

| Manipulation under anesthesia | 1 (1) | 271 |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 (1) | 20 |

Five patients had more than one major medical complication.

Table 3.

Economic impact of injury based on a minimum of 6 months follow-up

| Economic outcomes | % (n) |

| Returned to work, % (n) | 65 (71 of 110) |

| Absenteeism from work in months, median (IQR) | 7 (5-11) |

| Return to same employer, % (n) | 76 (54 of 71) |

| Return to same income or higher income, % (n) | 69 (49 of 71) |

| Return to same duties, % (n) | 68 (48 of 71) |

| Productivity level at the last follow-up visit,a median (IQR) | 9 (8-10) |

| Work status at the last follow-up visit, % (n) | |

| Working | 43 (71 of 164) |

| Unable to work | 25 (41 of 164) |

| Searching or training for work | 16 (27 of 164) |

| Sick leave | 5 (9 of 164) |

| Retired | 4 (6 of 164) |

| Other | 6 (10 of 164) |

| Disability compensation, % (n) | |

| None | 82 (135 of 164) |

| Disability benefits from employer | 6 (9 of 164) |

| Disability benefits from government | 6 (9 of 164) |

| Workers compensation | 4 (7 of 164) |

| Disability benefits from other sources | 2 (4 of 164) |

| Accumulated debt, % (n) | 45 (74 of 164) |

| Estimated debt from injury in USD, median (range)b | 6000 (640-130,000) |

| Debt to income ratio, median (range)b | 0.18 (0.01-4.0) |

Subjective assessment on a scale of 1 to 10.

Includes only the 74 participants who incurred debt.

Measured Outcomes and Variables

The primary endpoint was the patient’s subjective recovery priorities. The priorities were calculated using a discrete choice experiment and are reported as their importance on a scale of 0% to 100%. Discrete choice experiments are an established method to estimate decisional preferences between two or more discrete alternatives, such as the choice of health insurance coverage options [10, 13, 24, 25]. Using this approach, we created 48 hypothetical comparisons, called choice sets. Each choice set included two potential recovery scenarios described by several attributes. The attributes included whether the patient experienced a complication or had a complication-free physical recovery; whether they would return to work with the same employer, duties, and income; and whether disability benefits were received. We used focus groups and semistructured interviews with clinicians and patients who had experienced one or more fractures to inform the attributes and description of the attributes included in the choice sets. Specifically, we held two focus groups with 14 peer support members of the Trauma Survivors Network. Eight semistructured interviews were performed with three patients, two orthopaedic surgeons, two nurse practitioners, and one registered nurse. The 48 choice sets were based on a blocked orthogonal design that allocated the choice sets into four versions of the survey (12 choice sets per survey) with the goal of optimizing the number of hypothetical comparisons while minimizing each respondent’s burden. Having multiple versions of the survey also mitigated any question order bias that may arise with a single survey. We also randomly reordered the choice sets for each subsequent assessment. Each patient was randomly assigned to complete one version of the survey at each study timepoint. When completing the survey, patients were asked to select their preferred outcome for each choice set. If the patient presented to the clinic for a follow-up appointment, the surveys were administered in person. Otherwise, the survey was sent to the patient by email and completed in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) survey platform (Nashville, TN, USA) (Appendix 2; Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CORR/A483). Details on the development of the attributes and attribute levels for the study have been described [21].

The study also included several measures of economic well-being and major medical complications resulting in readmission or reoperation. The economic impact of the fracture was measured as days absent from work, return to work, disability compensation, and accumulated debt. The major medical complications included amputation, conversion to arthroplasty, bone healing nonunion, symptomatic hardware removal, manipulation under anesthesia, pulmonary embolism, deep surgical site infection, and wound dehiscence.

We recorded several patient characteristics and associated factors at baseline and at each follow-up evaluation as potential factors prognostic of patient recovery priorities. Time-constant covariates included age at the time of injury, sex, race, educational attainment, number of dependents at baseline, work status at the time of injury, and a preinjury occupation that involved physical labor. Time-varying covariates included a major medical complication as previously defined, postinjury debt, work status, a change in residence, and physical and mental health status as measured using the Patient-reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global health item bank [6].

Statistical Analysis

The target sample size for the study was 200 patients. This sample would provide 90% power to detect a 10% difference in the importance of a given recovery priority, assuming at least a 60% response rate at each follow-up visit, an SD of 0.15, three measurements, a correlation between measurements of 0.8, and a two-sided alpha of 0.05. The study sample did not have adequate statistical power to assess the association between biopsychosocial factors and the study outcomes. These comparisons should be considered exploratory.

Patient characteristics, economic outcomes, and medical complications are described using proportions with counts for categorical data and medians with IQRs or ranges for continuous data. We compared the characteristics of patients who completed the full follow-up with those who did not using X2 tests for categorical data, t-tests for normally distributed continuous data, and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal continuous data. We used hierarchical Bayesian modeling to calculate individual-level estimates of the importance of physical recovery, work-related recovery, and disability benefits based on the discrete choice experiment responses. Bayesian models differ from the more commonly used frequentist models by using prior probabilities and updating those probabilities with the observations from the study data to calculate effect estimates, known as posterior probabilities. Our particular models were hierarchical versions of this approach. For this study, the hierarchical, also called multilevel, models clustered responses by each study participant and version of the survey, incorporating the information gained from each previous question in the survey and previous surveys administered to a given respondent to form prior probabilities, thus deriving more precise estimates of patient priorities. Three models were initially created for three different aspects of work-related recovery (employer, duties, and income). The model that included income, along with clinical recovery and access to disability benefits, provided the best model fit, based on the average log-likelihood function across the three timepoints, and was used for the final analysis. We computed the coefficient of variation for the three recovery domains and compared between-patient and within-patient differences using asymptotic tests. The coefficient of variation is a unitless measure of dispersion calculated by dividing the SD of a sample by the mean. The change in the importance of recovery domains across the study timepoints was estimated using hierarchical Bayesian models to account for the correlation between repeated responses from a single patient. We developed a separate prognostic model for each of the study’s three recovery domains. All models assessed marginal changes in the importance of the recovery domain based on biopsychosocial factors that remained constant over the study period (for example, sex or preinjury work status) and biopsychosocial factors that varied over the study period (such as, work status or physical and mental health status). We used weak priors for all Bayesian models with 1000 warmup iterations, four Markov chains, and 10,000 iterations per chain. We report all estimates as the absolute mean difference with 95% credible intervals (CrI).

The discrete choice experiment surveys were developed, and the responses were modeled, using JMP version 14 (Cary, NC, USA). All other statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.0.0 (Vienna, Austria). Missing PROMIS assessment data at 6 and 12 months were imputed using multiple imputations [4]. Missing response data were assumed to be missing at random.

Results

Do Trauma Patients Consistently Identify a Specific Aspect/Domain of Recovery as Being Most Important at 6 Weeks, 6 Months, and 12 Months After Injury?

Trauma patients consistently identified physical recovery as the most important domain of recovery. The typical patient reported that physical recovery represented 60% ± 9% of their overall concern across the three study timepoints (Fig. 2). Work-related recovery was consistently the second most important recovery domain at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months after injury, and represented 27% ± 6% of their overall concern. Access to disability benefits remained the least important among the included recovery domains and was associated with 13% ± 7% of the overall concern within a year of injury.

Fig. 2.

Graph showing the crude estimates of the importance of recovery priorities after fractures. A color image accompanies the online version of this article.

Does the Relative Importance of Those Domains Change Within the First Year?

The relative importance of each domain changed within the first year after injury, but the overall hierarchy of the domains did not change at any timepoint (Table 4). The mean concern for physical recovery remained similar from 6 weeks to 6 months after injury but increased by 6% (95% CrI 4% to 7%) at 12 months after fracture compared with the 6-week estimates. The mean concern for work-related recovery increased by 7% (95% CrI 6% to 8%) from 6 weeks to 6 months after injury. However, the prioritization of work-related recovery at 12 months after injury was similar to 6-week estimates (0% [95% CrI 0% to 0%]). The mean importance of disability benefits increased by 2% (95% CrI 1% to 4%) at 6 months and by 2% (95% CrI 0% to 3%) at 12 months compared with 6-week estimates.

Table 4.

Change in the relative importance of recovery domains across study timepoints using hierarchical Bayesian models

| Domain | Time | Absolute difference (95% CI) |

| Physical recovery | ||

| 6 weeks | Ref (0.0) | |

| 6 months | 0.1% (0.0-0.3) | |

| 12 months | 5.8% (4.4-7.2) | |

| Work-related recovery | ||

| 6 weeks | Ref (0.0) | |

| 6 months | 7.4% (6.4-8.4) | |

| 12 months | 0.1% (0.0-0.3) | |

| Disability benefits | ||

| 6 weeks | Ref (0.0) | |

| 6 months | 2.4% (1.2-3.8) | |

| 12 months | 1.7% (0.4-2.9) | |

Are Differences in Priorities Greater Between Patients Than for a Given Patient Over Time?

Differences in priorities were greater within a given patient over time than between patients. The within-patient variation, as measured by the coefficient of variation, was greater than the between-patient variation for physical recovery (245% versus 7%; p < 0.001), work-related recovery (678% versus 12%; p < 0.001), and disability benefits (620% versus 33%; p < 0.001).

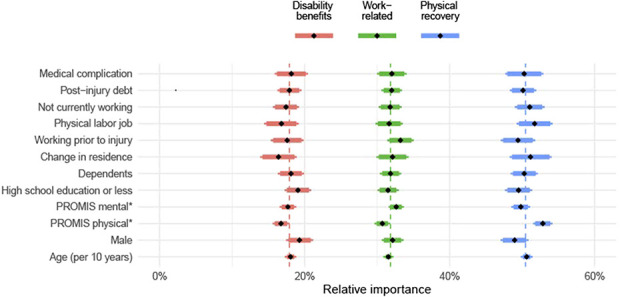

Are Different Recovery Priorities Associated with Identifiable Biopsychosocial Factors?

We found limited evidence that biopsychosocial factors were associated with variations in recovery priorities (Fig. 3). A 10-point increase in PROMIS physical health status score was associated with a 2% increase (95% CrI 1% to 3%) in the importance of physical recovery. A higher PROMIS mental health status score (1% per 10 points; 95% CrI 0% to 2%) was associated with an increased prioritization of work-related recovery.

Fig. 3.

Graph demonstrating heterogeneity in the importance of fracture recovery priorities associated with biopsychosocial factors. A color image accompanies the online version of this article.

Discussion

Value-based payment models aim to incentivize healthcare providers to offer services and resources that address the socioeconomic determinants impacting health outcomes. However, it is impossible to align services and resources for optimal use without first establishing patients’ priorities for physical, work-related, and financial recovery. The findings of this study substantially expand upon our prior publication providing clinicians, policy makers, and the research community a nuanced understanding of the variation in patients’ recovery priorities within 1 year of injury [21]. We observed patients’ concern for physical recovery exceeds their concern for work-related recovery and access to disability benefits in the year after injury. Patients’ concern for work-related recovery was heightened 6 months after injury but did not displace physical recovery as the patients’ paramount concern. Patient recovery priorities varied more within a given patient over the study duration than between patients. We were unable to identify biopsychosocial factors that meaningfully predicted patient recovery priorities.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Discrete choice experiments measure stated preferences, which may differ from revealed preferences. Patient comprehension of a survey is always a concern. To mitigate comprehension issues, all patients completed their first survey in the presence of a research staff member, who was available to answer questions during the survey and assess the respondent’s understanding after completing the initial survey. In addition, patients completed the survey at three distinct timepoints, improving their familiarity with the discrete choice experiment structure. Many other recovery domains were not included in the discrete choice experiment. However, we believe we included the most relevant priorities because our selection process was informed by focus groups and semistructured interviews with clinicians and patients who sustained a fracture [21]. Although the recovery priorities may be correlated [29], the discrete choice experiment is an effective method to disentangle the independent effects of correlated outcomes.

The study setting and eligibility criteria may limit the generalizability of the findings. The study was conducted at a single Level 1 trauma center. We only included patients who underwent surgery, and patients with spinal cord or traumatic brain injuries were excluded. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to fracture patients treated without surgery, those treated at a community hospital, or those with spinal cord or brain injuries. The respondents’ priorities may also be influenced by the socioeconomic situation and social welfare policies in Maryland, thus limiting the findings’ generalizability to other jurisdictions. The survey’s English-speaking requirement excluded 5% of the eligible patients. The socioeconomic circumstances and priorities of non-English-speaking patients may differ from the patients included in the study.

As 32% of the enrolled patients failed to complete their 12-month survey, attrition bias is a concern. Although this attrition level is far from ideal, it exceeds the 60% survey response rate threshold established in prior evidence [14]. The minimal differences in baseline characteristics between patients who responded at 12 months to those who did not complete their 12-month survey suggest the effects of this bias may be minimal. Further, our estimates were derived using hierarchical Bayesian models. One advantage of this type of model is that it treats missing response values as unique parameters and uses the distributions of the observed responses to form posterior estimates for the full sample conditioned on these missing values.

Do Trauma Patients Consistently Identify a Specific Aspect/Domain of Recovery as Being Most Important at 6 Weeks, 6 Months, and 12 Months After Injury?

Patients with trauma consistently identified physical recovery as the most important domain of recovery at all three timepoints. The observed hierarchy of priorities is consistent with prior research [26, 29] and may be explained by prospect theory [8]. Developed by Kahneman and Tversky [8], prospect theory posits that individuals place greater importance on losses than on a comparable gain. The common shared experience among the cohort was a traumatic injury. The loss of physical function was immediate, profound, and for many patients, persisted for months, if not longer. More than 30% of the sample were not working before their injury, and a lack of workforce participation would understandably decrease one’s concerns for work-related recovery.

Does the Relative Importance of Those Domains Change Within the First Year?

The relative importance of each domain remained constant throughout the study, but the importance of work-related recovery and disability benefits increased slightly at the 6- and 12-month timepoints. The trend of an increased concern for socioeconomic well-being after injury was consistent with research by Zatzick et al. [29]. The Family and Medical Leave Act covers most employees in Maryland with 12 weeks of unpaid job protection [3]. The 12 weeks of job protection prevent job loss for many patients and may reduce the prioritization of work-related recovery within 6 weeks after an injury. Work incapacity that exceeds 12 weeks likely increases the patient’s concern for work-related recovery and disability benefits. Due to delays in hospital billing, the patient may also not be fully aware of the financial implications of their injury at the 6-week survey.

Are Differences in Priorities Greater Between Patients Than for a Given Patient Over Time?

The time from injury was associated with more substantial variation in patient recovery priorities for a given patient than the observed variability between patients. Two studies have evaluated patient recovery priorities at a single timepoint [7, 26]. Few studies assessed the stability of preferences over some duration using repeated assessment of the same individuals [19, 29]. To our knowledge, only one study has compared within-person versus between-person preferences over time [19]. Although the study population was very different, a comparable pattern was observed. Mueller et al. [19] found fertility preferences to be unstable within individuals over time but consistent between individuals of similar ages.

Are Different Recovery Priorities Associated with Identifiable Biopsychosocial Factors?

We found little evidence to associate biopsychosocial factors with variations in recovery priorities. Prior research suggests that patients lacking preinjury employment and who have lower education levels have increased socioeconomic hardship after injury [7, 16]. Although our point estimates are consistent with these studies, our estimated effects are close to null and the overall hierarchy of priorities remain unchanged. Of note, a major medical complication leading to readmissions or reoperations was not associated with variation in recovery priorities. Our review of the patients’ medical records highlights the limitations of a medical complication to serve as a proxy for physical recovery challenges. A patient may be free of a major medical complication but experience dramatic physical disruptions. Patients often have pain, superficial wound complications, or bone healing challenges that inhibit activities of daily living but do not lead to readmission or reoperation. Factors such as comorbidities and injury severity were not included in the study and may influence patient recovery priorities. Finally, there may be other external policy factors that influence recovery priorities but were not explicitly captured in the analysis, such as labor market conditions and access to social insurance.

Conclusion

Physical recovery remained the primary recovery concern for patients with fractures during the 12 months after injury. However, the importance of work-related recovery and disability benefits was elevated after the subacute phase of injury. We were unable to identify patient characteristics that clearly predicted recovery priorities but did observe greater variation in recovery priorities within a given patient than between patients. As such, clinicians should routinely assess and reassess the socioeconomic well-being of all trauma patients. A clear understanding of patient recovery priorities can align available social interventions and resources with the patient’s preferences and social circumstances. However, determining which social interventions and resources are most effective in mitigating the socioeconomic effects of injury and improving health outcomes requires further research. Future studies should also investigate the factors associated with within-patient variation in priorities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Frannie Grissom BSN, and the members of the Trauma Survivors Network, who provided valuable feedback to the design of the discrete choice experiment questionnaire. We also thank Katherine Joseph MPH, Alexandra Mulliken BS, Kimberly Oslin BS, and Stephan Olaya BS, for their involvement in data collection.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (NNO, GPS) has received, during the study period, funding from the Osteosynthesis and Trauma Care Foundation.

Each author certifies that neither he nor she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore, MD, USA.

References

- 1.Bachrach D, Guyer J, Meier S, Meerschaert J, Brandel S. Enabling sustainable investment in social interventions: a review of Medicaid managed care rate-setting tools. Commonwealth Fund. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/grants/enabling-investment-effective-social-interventions-review-medicaid-managed-care-rate-setting. Accessed September 25, 2020.

- 2.Bhashyam AR, McGovern MM, Mueller T, Heng M, Harris MB, Weaver MJ. The personal financial burden associated with musculoskeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:1245-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkley DR, Kollner C. Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) guide. Available at: https://dbm.maryland.gov/employees/Documents/Leave/FMLA_Booklet.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 4.Buuren SV, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw . 2011;45:1-67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans RG. Supplier-induced demand: some empirical evidence and implications. In: Perlman M, ed. The Economics of Health and Medical Care . Macmillan; 1974:162-173. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res . 2009;18:873-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ioannou L, Cameron PA, Gibson SJ, et al. Financial and recovery worry one year after traumatic injury: a prognostic, registry-based cohort study. Injury. 2018;49:990-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263-291. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalofonos I. Biological citizenship - a 53-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder and PTSD applying for supplemental security income. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1985-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesternich I, Heiss F, McFadden D, Winter J. Suit the action to the word, the word to the action: hypothetical choices and real decisions in Medicare Part D. J Health Econ . 2013;32:1313-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreuter M, Garg R, Thompson T, et al. Assessing the capacity of local social services agencies to respond to referrals from health care providers. Health Aff (Millwood) . 2020;39:679-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehn BM. Hospitals turn to housing to help homeless patients. JAMA . 2019;321:822-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26:661-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston EH, Wislar JS. Minimum response rates for survey research. Arch Surg. 2012;147:110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Kellam JF, et al. Early predictors of long-term work disability after major limb trauma. J Trauma . 2006;61:688-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKenzie EJ, Morris JA, Jr, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Return to work following injury: the role of economic, social, and job-related factors. Am J Public Health . 1998;88:1630-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, eds. Frontiers in Econometrics . Academic Press; 1974:105-142. Available at: https://eml.berkeley.edu/reprints/mcfadden/zarembka.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McPherson K, Strong PM, Epstein A, Jones L. Regional variations in the use of common surgical procedures: within and between England and Wales, Canada and the United States of America. Soc Sci Med A. 1981;15:273-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller MW, Hicks JH, Johnson-Hanks J, Miguel E. The illusion of stable preferences over major life decisions. National Bureau of Economic Research. No. 25844. [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hara NN, Isaac M, Slobogean GP, Klazinga NS. The socioeconomic impact of orthopaedic trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One . 2020;15:e0227907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OʼHara NN, Mulliken A, Joseph K, et al. Valuing the recovery priorities of orthopaedic trauma patients after injury: evidence from a discrete choice experiment within 6 weeks of injury. J Orthop Trauma . 2019;33:S16-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Hara NN, Slobogean GP, Stockton DJ, Stewart CC, Klazinga NS. The socioeconomic impact of a femoral neck fracture on patients aged 18-50: a population-based study. Injury. 2019;50:1353-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Toole RV, Castillo RC, Pollak AN, MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ. Determinants of patient satisfaction after severe lower-extremity injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2008;90:1206-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan M. Discrete choice experiments in health care. BMJ. 2004;328:360-361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care . Springer Science and Business Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrime MG, Weinstein MC, Hammitt JK, Cohen JL, Salomon JA. Trading bankruptcy for health: a discrete-choice experiment. Value Health. 2018;21:95-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simske NM, Breslin MA, Hendrickson SB, York KP, Vallier HA. Implementing recovery resources in trauma care: impact and implications. OTA International . 2019:e045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, et al. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg . 2008;248:429-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Hinton WL, et al. Posttraumatic concerns: a patient-centered approach to outcome assessment after traumatic physical injury. Med Care . 2001;39:327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.