Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant influence on the lives of people around the world and could be a risk factor for mental health diseases. This study aimed to explore the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by identifying patterns related to post-traumatic symptoms by considering personality and defensive styles. Specifically, it was hypothesized that neuroticism was negatively associated with impact of event, as opposed to extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness traits. The mediation role of mature, neurotic, and immature defenses in these relationships was also investigated. This study involved 557 Italian individuals (71.3% women, 28.7% men; Mage = 34.65, SD = 12.05), who completed an online survey including the Impact of Event Scale—Revised, Forty Item Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40) and Ten Item Personality Inventory. Results showed a nonsignificant effect for extraversion and openness on impact of event. The negative influence of neuroticism was instead confirmed in a partial parallel mediation involving significant effects from immature and neurotic defenses in the indirect path. Finally, agreeableness and conscientiousness delineated two protective pathways regarding impact of event, determining two total parallel mediation models in which both these personality traits were negatively associated with immature defensive styles, and conscientiousness was also positively related to mature defenses. These findings provide an exploration post-traumatic symptom patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, involving the big five personality traits and defense mechanisms. These results may be useful for developing interventions, treatments, and prevention activities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound influence on the lives of people around the world [1–3]. It has an impact not only on the sphere of physical health [4], but its effects extended to individual and collective levels in behavioral and economic areas [5, 6]. The protective measures adopted in countries to stem the spread of the pandemic, by requiring the adoption of new protective habits, have significantly impacted the world economy, causing many people to be in a state of financial instability and uncertainty about the future [7, 8]. This scenario had repercussions on organizations and the health of workers [9]. Indeed, all this could have a profound effect on mental health [10]. Both the restrictive measures adopted by governments and the spread of the virus itself were associated with lower levels of life satisfaction and wellbeing [11, 12] and with higher levels of anxiety [13–16], depression [17], anger [18], fear, and worry [18–20], resulting in fertile ground for the development of distress and chronic psychological symptoms in some people [21]. In fact, previous research has consistently identified symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [14, 22–25], which could last beyond the course of the pandemic. PTSD, in turn, was associated with poorer physical health, suicide attempts, and impairment in different areas of life [26, 27]. Regarding organizations, from a healthy business perspective [28], healthy organizations require healthy workers [29]. In this framework, this study aims to foster a better understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on mental health, identifying patterns related to post-traumatic symptoms by considering personality and defensive styles.

The psychological and behavioral responses to the pandemic can be influenced by several factors, including a person’s characteristics and resources [30, 31], as evidenced by previous research that has highlighted the significant influence of personality traits on reactions to stress [32, 33]. In this field, the Big Five Model of Costa and McCrae [34] is one of the most frequently used, in which five dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness) represent a coherent and basically stable set of aspects that influence the affects, thoughts, and behaviors of individuals in their different life experiences. Among these, neuroticism appears to be a relevant risk factor in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in problematic conditions [35]. Individuals with less emotional stability reported more intense and lasting emotional responses, associated with a tendency to perceive the impact of stressful events with greater intensity [36, 37]. Conversely, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness have been associated with functional and active strategies for solving problems in difficult situations such as seeking support, positive reinterpretation, growth, and acceptance [38]. These dimensions have been consistently positively associated with subjective wellbeing and life satisfaction [39]. Personality traits, therefore, can shape an individual’s responses to life situations by influencing their cognitive assessments, the emotions associated with them, and the strategies used to regulate those affective activations [38, 40]. Other relevant factors in managing the psychological impact of stressful events are defenses, which can be defined as mechanisms that "mediate the individual’s reaction to emotional conflicts and external stressors" [41] (p. 844) and may be more or less adaptive depending on the context in which their occur. In other words, psychological health is not only linked to the application of mature defense strategies, but above all to the appropriate use of a variety of defenses based on the circumstances [42]. To confirm this, previous research has shown an inverse association between adaptive levels of defensive functioning and perceived distress, depressive, and post-traumatic symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [43, 44].

On this basis, the aim of this work is to contribute to the knowledge of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, a series of parallel mediation models were implemented to analyze the relationships between personality traits and post-traumatic symptoms. More specifically, it was hypothesized that neuroticism was negatively associated with impact of event, contrary to the traits of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness, for which a positive relationship is assumed. The mediation role of mature, neurotic, and immature defenses in these pathways was also explored.

Method

Participants and procedures

The participants in this study were 557 Italian individuals (ages 18–88 years; M = 34.65, SD = 12.05), 397 of which were woman (71.3%) and 160 were man (28.7%). They were recruited during the COVID-19 pandemic on the internet by circulating a link to a survey administered through the Google Forms platform. The survey was launched on March 24th, 2020 and remained open until March 31st, 2020. Before starting, participants were informed about the general aim of the study and provided with informed consent electronically. Data was anonymously collected, and the privacy of the respondents was guaranteed. Participants did not receive compensation for being involved in the study and were free to withdraw at any moment. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Integrated Psychodynamic Psychotherapy Institute (IPPI).

Measures

Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R)

The Impact of Event Scale—Revised (IES-R) is a self-report measure developed by Weiss and Marmar [45] to assess the level of post-traumatic symptomatology resulting from a traumatic event. It is composed of 22 items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). In addition to a total score, it also allows for evaluation of three subdimensions: intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. The Italian version, previously validated by Craparo and colleagues [46], was used in this study. It has satisfactory psychometric properties, showing adequate internal consistency for each subscale (intrusion, α = .78; avoidance, α = .72; hyperarousal, α = .83) [46], as well as excellent Cronbach’s α for the total score (α = .95) in Italian populations during the COVID-19 pandemic [47].

Forty Item Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40)

The Forty Item Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ-40) was developed by Andrews and colleagues [48] to assess the degree to which the respondent uses mature, neurotic, or immature defense mechanisms. It included 40 items on a nine-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). In the present study, the Italian version, previously validated by Farma and Cortinovis [49] and showing acceptable psychometric properties (mature defense: α = .61; neurotic defense: α = .59; immature defense: α = .80), was administered.

Italian Ten Item Personality Inventory (I-TIPI)

The Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) was developed by Gosling and colleagues [50] to assess personality traits in terms of the big five model [51]. It includes 10 items on an eight-point scale ranging from 0 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). It allows for the evaluation of five personality traits: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. In this study, the Italian version by Di Fabio, Gori, and Giannini [52] was used, showing satisfactory psychometric properties (from α = .78 for agreeableness, to α = .82 for extraversion) [52].

Data analysis

SPSS statistical software (v. 25.0 for windows) was used to analyze the collected data. First, means and standard deviations for all scales were calculated. Then, a Pearson’s correlation analysis was implemented to evaluate the associations between the variables under study. To assess the effect of the different personality traits on impact of event during the COVID-19 pandemic, while exploring the role of the defense mechanisms in this relationship, several parallel mediation models were tested using the macro-program PROCESS 3.4 [53]. The output variable of these models was the total score of the IES-R, although the scale also has sub-dimensions, as it includes partial scores and therefore guarantees a broader detection of the extent of the event. For each regression coefficient included in the models, the 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. Finally, the statistical relevance of the indirect effects was verified by performing the bootstrap technique for each of the 5,000 bootstrapped samples within 95% of the confidence interval.

Results

Means and standard deviations of the measures and Pearson’s correlation matrix are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations, means and standard deviations of the variables.

| 1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | M | SD | |

| 1. Impact of event | 1 | 33.05 | 16.75 | |||||||||||

| 1.1 Intrusion | .844** | 1 | 11.52 | 6.06 | ||||||||||

| 1.2 Avoidance | .932** | .650** | 1 | 12.18 | 7.18 | |||||||||

| 1.3 Hyperarousal | .906** | .625** | .826** | 1 | 9.35 | 5.46 | ||||||||

| 2.1 Mature defenses | -.016 | .059 | -.037 | -.066 | 1 | 42.89 | 9.47 | |||||||

| 2.2 Neurotic defenses | .394** | .347** | .376** | .330** | .278** | 1 | 34.30 | 10.07 | ||||||

| 2.3 Immature defenses | .396** | .361** | .347** | .358** | .276** | .526** | 1 | 95.18 | 25.91 | |||||

| 3.1 Extraversion | .003 | .026 | -.011 | -.005 | .126** | -.002 | -.029 | 1 | 7.65 | 3.27 | ||||

| 3.2 Agreeableness | -.118** | -.065 | -.094* | -.166** | .058 | .051 | -.302** | -.221** | 1 | 9.95 | 2.42 | |||

| 3.3 Conscientiousness | -.090* | -.056 | -.101* | -.081 | .157** | -.083 | -.211** | .011 | .125** | 1 | 10.56 | 2.58 | ||

| 3.4 Neuroticism | .457** | .327** | .424** | .481** | -.220** | .219** | .332** | -.060 | -.273** | -.337** | 1 | 7.84 | 3.12 | |

| 3.5 Openness | -.049 | -.063 | -.041 | -.028 | .090* | -.022 | -.112** | .258** | .010 | -.027 | -.020 | 1 | 12.18 | 7.18 |

Note:

**. Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

Results highlighted significant and positive associations of impact of event with neurotic defenses (r = .394, p < .01), immature defenses (r = .396, p < .01), and neuroticism (r = .457, p < .01), as well as negative significant relationships with agreeableness (r = -.118, p < .01) and conscientiousness (r = -.090, p < .05). Furthermore, immature defenses were negatively and significantly correlated with agreeableness (r = -.302, p < .01), conscientiousness (r = -.211, p < .01), and openness (r = -.112, p < .01), while they were positively and significantly related to neuroticism (r = .332, p < .01). The mature defenses scale was significantly and positively correlated with conscientiousness (r = .157, p < .01) and openness (r = .090, p < .05) and showed a significant and negative association with neuroticism (r = -.220, p < .01). Finally, a significant and positive relation was found between neuroticism and neurotic defenses (r = .219, p < .01).

A series of parallel mediations was performed to investigate the contributions of the different to the effects between personality traits and impact of event (see Table 2). The results showed that the effect of extraversion on impact of event was nonsignificant (β = .00, p = .948; LLCI = -.412—ULCI = .441), as was for openness (β = -.050, p = .244; LLCI = -.874—ULCI = .223).

Table 2. Models effect indices.

| Independent variable | Parallel mediators | Dependent variable | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [95% CI | |||||

| indirect effect] | |||||

| Extraversion | Mature defenses | Impact of event | .003 | .035 | -.032 |

| Neurotic defenses | [-.392; .054] | ||||

| Immature defenses | |||||

| Agreeableness | Mature defenses | Impact of event | -.118** | -.041 | -.077 |

| Neurotic defenses | [-.897; -.187] | ||||

| Immature defenses | |||||

| Conscientiousness | Mature defenses | Impact of event | -.090* | .026 | -.116 |

| Neurotic defenses | [-1.046; -.471] | ||||

| Immature defenses | |||||

| Neuroticism | Mature defenses | Impact of event | .457*** | .334*** | .123 |

| Neurotic defenses | [.407; .939] | ||||

| Immature defenses | |||||

| Openness | Mature defenses | Impact of event | -.050 | .006 | -.056 |

| Neurotic defenses | [-.658; -.079] | ||||

| Immature defenses |

Note:

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

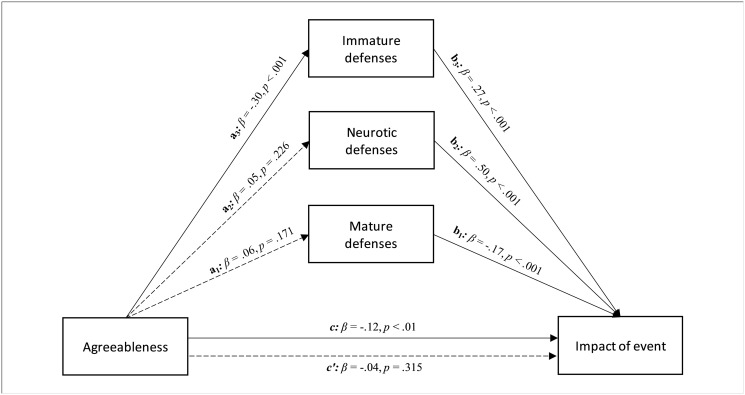

On the other hand, the data showed that agreeableness had a significant and negative effect on impact of event (path c in Fig 1; β = -.12, p < .01; LLCI = -1.392—ULCI = -.244). Furthermore, the agreeableness trait had an nonsignificant effect on both mature (path a1 in Fig 1; β = .06, p = .171; LLCI = -.099—ULCI = .554) and neurotic defenses (path a2 in Fig 1; β = .05, p = .226; LLCI = -.133—ULCI = .561), but it significantly and negatively affected immature defenses (path a3 in Fig 1; β = -.30, p < .001; LLCI = -4.086—ULCI = -2.382), which in turn were positively associated with impact of event (path b3 in Fig 1; β = .27, p < .001; LLCI = .115—ULCI = .238). Entering the three defensive styles in the model parallelly, only immature defenses played a statistically significant role in the relationship between agreeableness and impact of event, at a level whose direct effect was nonsignificant after controlling the mediators (path c’ in Fig 1; β = -.04, p = .315; LLCI = -.839—ULCI = .271). Therefore, a total mediation occurred (R2 = .234, F(4, 552) = 42.158, p < .001; see Fig 1). The bootstrap procedure confirmed the statistical relevance of this indirect effect (Boot LLCI = .112- Boot ULCI = .240).

Fig 1. The relationship between agreeableness and impact of event, with different levels of defenses as parallel mediators: A parallel mediation model.

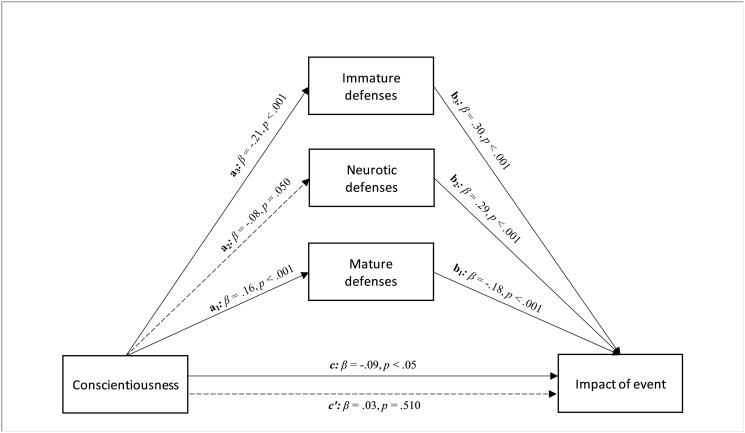

The parallel mediation model involving conscientiousness highlighted its significant and negative total effect on impact of event (path c in Fig 2; β = -.09, p < .05; LLCI = -1.122—ULCI = -.045). Conscientiousness was also significantly and positively related to mature defenses (path a1 in Fig 2; β = .16, p < .001; LLCI = .272—ULCI = .876) and significantly and negatively associated with immature defenses (path a3 in Fig 2; β = -.21, p < .001; LLCI = -2.927—ULCI = -1.293), while showing a nonsignificant effect on neurotic defenses (path a2 in Fig 2; β = -.08, p = .05; LLCI = -.647—ULCI = -.000). On the other hand, the effect of mature defenses on impact of event was significant (path b1 in Fig 2; β = -.18, p < .001; LLCI = -.464—ULCI = -.184), as well as that of the immature defenses (path b3 in Fig 2; β = .30, p < .001; LLCI = .136—ULCI = .252). Entering the three defensive styles in the model parallelly, mature and immature defenses played a significant role in the relationship between conscientiousness and impact of the event, at a level whose direct effect became nonsignificant after controlling the mediators (path c’ in Fig 2; β = .03, p = .511; LLCI = -.332—ULCI = .666). Therefore, a total mediation occurred (R2 = 0.233, F(4, 552) = 41.969, p < .001; see Fig 2). The bootstrap procedure confirmed the statistical relevance of this indirect effect (Boot LLCI = .132- Boot ULCI = .252).

Fig 2. The relationship between conscientiousness and impact of event, with different levels of defenses as parallel mediators: A parallel mediation model.

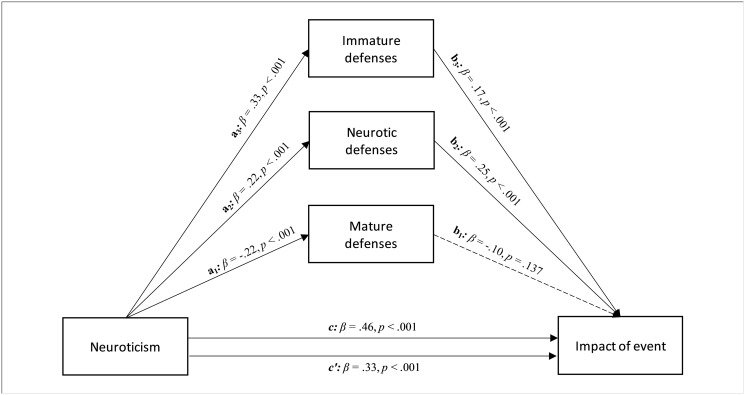

Finally, the personality trait of neuroticism showed a significant and positive total effect on impact of event (path c in Fig 3; β = .46, p < .001; LLCI = 2.058—ULCI = 2.855). Furthermore, neuroticism had significant effects on mature (path a1 in Fig 3; β = -.22, p < .001; LLCI = -.915—ULCI = -.420), neurotic (path a2 in Fig 3; β = .22, p < .001; LLCI = .445—ULCI = .971), and immature defenses (path a3 in Fig 3; β = .33, p < .001; LLCI = 2.102—ULCI = 3.410). In turn, the neurotic style was significantly related to impact of event (path b2 in Fig 3; β = .25, p < .001; LLCI = .273—ULCI = .559), as well as the immature defenses (path b3 in Fig 3; β = .17, p < .001; LLCI = .055—ULCI = .168). Entering the three defensive styles in the model parallelly, mature and immature defenses played a significant role in the relationship between conscientiousness and impact of event, albeit remaining significant after controlling the mediators (path c’ in Fig 3; β = .33, p < .001; LLCI = 1.367—ULCI = 2.211). Therefore, a total mediation occurred (R2 = 0.318 F(4, 552) = 64.447, p < .001; see Fig 3). The bootstrap procedure confirmed the statistical relevance of this indirect effect (Boot LLCI = .053- Boot ULCI = .168).

Fig 3. The relationship between neuroticism and impact of event, with different levels of defenses as parallel mediators: A parallel mediation model.

The coefficients of the significant parallel mediation models are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Coefficients of the mediation models.

| Parallel mediation of different levels of defenses on the relationship between Agreeableness and Impact of event | ||||||||||||||||

| Consequent | ||||||||||||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | Y | |||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||||

| X1 | a1 | .228 | .166 | .171 | a2 | .214 | .177 | .226 | a3 | -3.234 | .434 | < .001 | c’ | -.284 | .282 | .315 |

| M1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | -.305 | .070 | < .001 | |||

| M2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | .470 | . 076 | < .001 | |||

| M3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | .177 | . 031 | < .001 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 40.626 | 1.701 | < .001 | iM2 | 32.163 | 1.809 | < .001 | iM2 | 127.371 | 4.443 | < .001 | iY | 15.010 | 4.529 | .001 |

| R2 = 0.003 | R2 = 0.003 | R2 = 0.091 | R2 = 0.234 | |||||||||||||

| F(1, 555) = 1.876, p = .171 | F(1, 555) = 1.472, p = .226 | F(1, 555) = 55.581, p < .001 | F(4, 552) = 42.158, p < .001 | |||||||||||||

| Parallel mediation of different levels of defenses on the relationship between Conscientiousness and Impact of event | ||||||||||||||||

| Consequent | ||||||||||||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | Y | |||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||||

| X2 | a1 | -.574 | .154 | < .001 | a2 | -.323 | .165 | .050 | a3 | -2.110 | .416 | < .001 | c’ | .167 | .254 | .022 |

| M1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | -.324 | .071 | < .001 | |||

| M2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | .481 | . 074 | < .001 | |||

| M3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | .194 | . 030 | < .001 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 36.833 | 1.670 | < .001 | iM2 | 37.710 | 1.791 | < .001 | iM2 | 117.457 | 4.521 | < .001 | iY | 10.220 | 4.294 | .018 |

| R2 = 0.025 | R2 = 0.007 | R2 = 0.044 | R2 = 0.233 | |||||||||||||

| F(1, 555) = 13.946, p < .001 | F(1, 555) = 3.853, p = .050 | F(1, 555) = 25.735, p < .001 | F(4, 552) = 41.969, p < .001 | |||||||||||||

| Parallel mediation of different levels of defenses on the relationship between Neuroticism and Impact of event | ||||||||||||||||

| Consequent | ||||||||||||||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | Y | |||||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | ||||

| X3 | a1 | -.667 | .126 | < .001 | a2 | .708 | .134 | < .001 | a3 | 2.756 | .333 | < .001 | c’ | 1.789 | .215 | < .001 |

| M1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b1 | -.104 | .070 | .137 | |||

| M2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b2 | .411 | . 070 | < .001 | |||

| M3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | b3 | .111 | . 029 | < .001 | |||

| Constant | iM1 | 48.121 | 1.062 | < .001 | iM2 | 28.746 | 1.128 | < .001 | iM2 | 73.582 | 2.807 | < .001 | iY | -1.172 | 3.551 | .742 |

| R2 = 0.048 | R2 = 0.048 | R2 = 0.332 | R2 = 0.318 | |||||||||||||

| F(1, 555) = 28.110, p < .001 | F(1, 555) = 28.019, p < .001 | F(1, 555) = 68.548, p < .001 | F(4, 552) = 64.447, p < .001 | |||||||||||||

Note: X1 = Agreeableness; X2 = Conscientiousness; X3 = Neuroticism; M1 = Mature defenses; M2 = Neurotic defenses; M3 = Immature defenses; Y = Impact of event

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global emergency that represents a significant risk not only for physical health [4], economic conditions, and healthy organizations [7, 29] but also for the psychological health of individuals. This is due to its numerous direct and indirect consequences in the psychological and social spheres [8] that could persist even after the pandemic ends [54]. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the pathways leading to post-traumatic symptoms by investigating the big five personality traits and their interactions with mature, neurotic, and immature defenses in their association with impact of event.

As expected, the results highlighted that neuroticism was the personality trait with the strongest total effect on impact of event, showing a significant positive association both directly and indirectly. Indeed, previous studies during the pandemic have found significant associations between this personality trait and generalized anxiety, depressive symptoms, worries, and pessimism related to COVID-19 [15, 55]. In line with this, other research has shown that people with high levels of neuroticism tend to react with intense negative emotional responses to frustration or loss, report worsening mental health conditions after stressful events, and were more at risk of post-traumatic symptoms [36, 37, 56, 57]. Furthermore, the data have shown that neuroticism also had an indirect effect on the impact of event through the significant influence of immature and neurotic defense mechanisms. This appears to be consistent with previous studies [58] that showed lower psychological adaptation skills in subjects with this personality trait during the pandemic. This was expressed through negative responses to stress linked to a lower level of resilience, which in turn, in other traumatogenic contexts, has shown a negative association with post-traumatic symptoms [59, 60].

The data also showed two protective pathways that involved agreeableness and conscientiousness, which interacted directly with defense mechanisms and only indirectly with impact of event. Specifically, both these personality traits were negatively associated with immature defensive styles, which represented a risk factor for mental health [61, 62]; furthermore, conscientiousness was positively related to mature defenses. Both of these indirect paths limited the level of impact of event, in line with the evidence in existing scientific literature about the positive association of agreeableness and conscientiousness with subjective wellbeing [39]. Indeed, previous research showed a negative relationship of agreeableness with anxiety and depression during the pandemic [63], while individuals with conscientiousness traits demonstrated greater compliance with prevention guidelines related to the COVID-19 [64]. Taken together, these results suggest the positive influence of these dispositions on the tendency to use effective strategies to face difficulties [65].

Finally, contrary to expectations, neither extraversion nor openness showed a significant association with impact of event. These results could be an expression of the specific situation involving COVID-19. Indeed, although previous research showed an association of extraversion and openness with higher levels of positive emotions and subjective wellbeing [39], the restrictions and preventive measures implemented to stem the pandemic could have attenuated the use of functional strategies usually associated with these personality traits, without going so far as to make them maladaptive. In other words, the level of adaptation can vary depending on the environment and the historical period [66].

These results need to be interpreted with caution, because of the limitations that should be considered. First, the participants in this study may not have been representative of the general population (e.g., they were recruited online, and this excluded people who did not have internet access). Secondly, a sectional design was used to implement this research, which does not allow for causal inference. Furthermore, the socioeconomic status of the participants was not explored, and this could be an interesting future challenge in light of previous evidence concerning the association between economic stratification and distress due to COVID-19 [e.g., 67]. In association with that, detailed information on the "remote" or "in presence" working condition and about the type of job was not collected: this can significantly affect the development of PTSD (especially with regards to health professionals who during the lockdown continued to work intensely while in contact with patients) [68] or, for example, enhance different perception of contagion risk between individuals with consciousness traits or, on the opposite, with higher levels of neuroticism.

Future research could overcome these limitations by implementing a longitudinal design, using a paper-pencil administration technique, and with a more comprehensive sample in which the differences in the psychological effect of COVID-19 may be explored, while considering socioeconomic and working conditions.

Conclusion

The results of this research highlighted the association between the big five personality traits, defense mechanisms, and impact of event during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, agreeableness and conscientiousness proved to be factors that may favor a more functional use of defense mechanisms. They were also negatively associated with the presence of post-traumatic symptoms, the opposite of what emerged for the neurotic trait. The understanding of the pathways involved in psychological distress during the pandemic may have practical implications for providing effective assistance to the population in terms of both individuals in personal contexts and workers in organizational contexts. This study can contribute by proposing differentiated interventions and treatments, starting from a better understanding of the defensive strategies used in relation to dispositional aspects. In this regard, these data suggest the usefulness of intervening to increase and support the use of mature defensive styles for dealing with the stressful experiences related to COVID-19 [69]. Treatments could focus, for example, on favoring increases in mentalizing or insight levels, which were positively associated with functional defenses and inversely with maladaptive defensive mechanisms [70, 71], as well as related to higher levels of mental health, meaningfulness, and satisfaction [72–74]. Finally, the psychological vulnerability of subjects with the trait of neuroticism was highlighted [15, 55], underlining the need to place a greater focus on both intervention and preventive perspectives in different life contexts. In this regard, it may be functional to intervene to limit the emotional dysregulation characterizing this trait, for example by implementing treatments focused on reducing alexithymia, which is negatively associated with the use of mature defenses [75], and was related to poorer mental health in both clinical and non-clinical subjects [76–78].

Data Availability

All data files are available from the Figshare database (doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.14139944).

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public–A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 113190. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maria N, Zaid A, Catrin S, Ahmed K, Ahmed AJ, Christos I, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020;78: 185–193. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020; 277: 55–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18): 1708–1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazziti D, Stahl SM. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2): 261. 10.1002/wps.20764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen MJ, Favero N. Social Distancing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Who Are the Present and Future Noncompliers?. Public Adm. Rev. 1010;80(5): 805–814. 10.1111/puar.13240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blustein DL, Kenny ME, Di Fabio A, Guichard J. Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. J Career Assess. 2019;27(1): 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1069072718774002 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Bavel JJ, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M., et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4(5): 460–471. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez I, Kozusznik MW, Peiró JM, Tordera N. Individual, co-active and collective coping and organizational stress: A longitudinal study. Eur. Manag. J., 2019:37(1): 86–98. 10.1016/j.emj.2018.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry. 1010;63(1): e32. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020;89(4): 242–250. 10.1159/000507639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020;51: 102092. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020;1–9. 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(5): 1729. 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SA, Jobe MC, Mathis AA, Gibbons JA. Incremental validity of coronaphobia: Coronavirus anxiety explains depression, generalized anxiety, and death anxiety. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020;74: 102268. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SA, Mathis AA, Jobe MC, Pappalardo EA. Clinically significant fear and anxiety of COVID-19: A psychometric examination of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290: 113112. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health. 2020;16(1): 1–11. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020;66(4): 317–320. 10.1177/0020764020915212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikčević AV, Spada MM. The COVID-19 Anxiety Syndrome Scale: development and psychometric properties. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292: 113322. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gori A, Topino E, Craparo G, Lauro Grotto R, Caretti V (2021). An empirical model for understanding the threat responses at the time of COVID-19. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021; 9(1). 10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp-2916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287: 112921. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyraz G, Legros DN. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and traumatic stress: probable risk factors and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Loss Trauma. 2020;25(6–7): 503–522. 10.1080/15325024.2020.1763556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, McIntyre RS, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87: 40–48. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Murphy J, McBride O, Ben-Ezra M, Bentall RP, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and associated comorbidity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland: A population-based study. J. Trauma. Stress. 2020;33(4): 365–370. 10.1002/jts.22565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun L, Sun Z, Wu L, Zhu Z, Zhang F, Shang Z, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for acute posttraumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;283: 123–129. 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferry FR, Brady SE, Bunting BP, Murphy SD, Bolton D, O’Neill SM. The economic burden of PTSD in Northern Ireland. J. Trauma. Stress. 2015;28(3): 191–197. 10.1002/jts.22008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Stein MB, Afifi TO, Fleet C, Asmundson GJ. Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosom. Med. 2007;69(3); 242–248. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31803146d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Fabio A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. Organ. Psychol. 2017;8;1938. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Fabio A, Cheung F, Peiró J-M. Editorial Special Issue Personality and individual differences and healthy organizations. Pers. Indiv. Differ., 2020;166. 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. In: Cooper CL, Quick JC editors. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2017. pp. 351–364 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Crosta A, Palumbo R, Marchetti D, Ceccato I, La Malva P, Maiella R. et al. Individual differences, economic stability, and fear of contagion as risk factors for PTSD symptoms in the COVID-19 emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020;11: 2329. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bibbey A, Carroll D, Roseboom TJ, Phillips AC, de Rooij SR. Personality and physiological reactions to acute psychological stress. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013;90(1): 28–36. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oshio A, Taku K, Hirano M, Saeed G. Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2018;127: 54–60. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa PT Jr, McCrae RR. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. J. Pers. Disord. 1990;4(4): 362–371. 10.1521/pedi.1990.4.4.362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puechlong C, Weiss K, Le Vigouroux S, Charbonnier E. Role of personality traits and cognitive emotion regulation strategies in symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among flood victims. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020;50: 101688. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breslau N, Schultz L. Neuroticism and post-traumatic stress disorder: a prospective investigation. Psychol. Med. 2013;43(8): 1697–1702. 10.1017/S0033291712002632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussain A, Weisæth L, Heir T. Posttraumatic stress and symptom improvement in Norwegian tourists exposed to the 2004 tsunami—a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:232. 10.1186/1471-244X-13-232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afshar H, Roohafza HR, Keshteli AH, Mazaheri M, Feizi A, Adibi P. The association of personality traits and coping styles according to stress level. J. Res. Med. 2015;20(4): 353–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anglim J, Horwood S, Smillie LD, Marrero RJ, Wood JK. Predicting psychological and subjective well-beingfrom personality: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020;146: 279–323. 10.1037/bul0000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cramer P. Protecting the self: Defense mechanisms in action. Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Giuseppe M, Zilcha-Mano S, Prout TA, Perry JC, Orrù G, Conversano C. Psychological impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 among Italians during the first week of lockdown. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11: 576597. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.576597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gori A, Topino E, Di Fabio A. The protective role of life satisfaction, coping strategies and defense mechanisms on perceived stress due to COVID-19 emergency: A chained mediation model. Plos one, 2020;15(11): e0242402. 10.1371/journal.pone.0242402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Guilford, New York; 1996. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craparo G, Faraci P, Rotondo G, Gori A, The Impact of Event Scale–Revised: psychometric properties of the Italian version in a sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2013;9: 1427–1432. 10.2147/NDT.S51793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forte G, Favieri F, Tambelli R, Casagrande M. The enemy which sealed the world: effects of COVID-19 diffusion on the psychological state of the Italian population. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(6): 1802. 10.3390/jcm9061802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrews G., Singh M., & Bond M., 1993. The Defense Style Questionnaire. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 181(4), 246–256. 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farma T, Cortinovis I. Misurare i meccanismi di diffesa attraverso il "Defense Style Questionnaire" a 40 item. Attendibilita’ dello strumento e suo utilizzo nel contesto Italiano [Measuring defense mechanism through the 40 items of the "Defense Style Questionnaire." Reliability of the instrument and its use in the Italian context]. Ric. di Psicol., 2000;24(3–4): 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gosling S, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. Ten-Item Personality Inventory-(TIPI). J. Res. Pers. 2003;37: 504–528. 10.1037/t07016-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess.1992;4(1): 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Fabio A, Gori A, Giannini M. Analysing the psychometric properties of a Big Five measure with an alternative method: The example of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI). Counseling: Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni; 2016. http://rivistedigitali.erickson.it/counseling/. accessed 13 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis second edition: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holmes EA, O’Connor, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6): 547–560. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Sesker AA, Lee JH, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, et al. Psychological and behavioural responses to Coronavirus disease 2019: The role of personality. Eur. J. Pers. 2021;35(1): 51–66. 10.1002/per.2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frazier P, Gavian M, Hirai R, Park C, Tennen H, Tomich P, et al. Prospective predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: direct and mediated relations. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2011;3: 27–36. 10.1037/a0019894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin Q, Wu L, Yu X, Liu W. Neuroticism predicts a long-term PTSD after earthquake trauma: the moderating effects of personality. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10: 657. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kocjan GZ, Kavčič T, Avsec A. Resilience matters: Explaining the association between personality and psychological functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021;21(1), 100198. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gori A, Topino E, Sette A, Cramer H. Pathways to post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: moderated mediation and single mediation analyses with resilience, personality, and coping strategies. J. Affect. Disord. 2021a;279: 692–700. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gori A, Topino E, Sette A, Cramer H. Mental health outcomes in patients with cancer diagnosis: Data showing the influence of resilience and coping strategies on post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic symptoms. Data Brief. 2021a;34: 106667. 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bond M, Perry JC. Long-term changes in defense styles with psychodynamic psychotherapy for depressive, anxiety, and personality disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161(9): 1665–1671. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zanarini MC, Weingeroff JL, Frankenburg FR. Defense mechanisms associated with borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2009;23(2): 113–121. 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.2.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nikčević AV, Marino C, Kolubinski DC, Leach D, Spada MM. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279: 578–584. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bogg T, Milad E. Demographic, personality, and social cognition correlates of coronavirus guideline adherence in a US sample. Health Psychol. 2020;39(12): 1026–1036. 10.1037/hea0000891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agbaria Q, Mokh AA. Coping with Stress During the Coronavirus Outbreak: the Contribution of Big Five Personality Traits and Social Support. Int J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021; 1–19. 10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur. Psychol.2013;18: 12–23. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prout TA, Zilcha-Mano S, Aafjes-van Doorn K, Békés V, Christman-Cohen I, Whistler K, et al. Identifying predictors of psychological distress during COVID-19: a machine learning approach. Front. Psychol. 2020;11: 586202. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson SU, Ebrahimi OV, Hoffart A. PTSD symptoms among health workers and public service providers during the COVID-19 outbreak. PloS one. 2020;15(10): e0241032. 10.1371/journal.pone.0241032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker G, McCabe T. Psychological defence mechanisms during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case series. Eur. J. Psychiatry. 2021;35(1) 41–45. 10.1016/j.ejpsy.2020.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tanzilli A, Di Giuseppe M, Giovanardi G, Boldrini T, Caviglia G, Conversano C, et al. Mentalization, attachment, and defense mechanisms: a Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual-2-oriented empirical investigation. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 2021;24(1): 31–41. 10.4081/ripppo.2021.531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thirioux B, Harika-Germaneau G, Langbour N, Jaafari N. The relation between empathy and insight in psychiatric disorders: phenomenological, etiological, and neuro-functional mechanisms. Front. Psychiatry 2020;10: 966. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gori A, Arcioni A, Topino E, Craparo G, Lauro Grotto R. Development of a New Measure for Assessing Mentalizing: The Multidimensional Mentalizing Questionnaire (MMQ). J. Pers. Med. 2021;11(4): 305. 10.3390/jpm11040305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gori A, Craparo G, Giannini M, Loscalzo Y, Caretti V, La Barbera D, et al. Development of a new measure for assessing insight: psychometric properties of the insight orientation scale (IOS). Schizophr. Res. 2015;169(1–3): 298–302. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gori A, Topino E. Predisposition to change is linked to job satisfaction: Assessing the mediation roles of workplace relation civility and insight. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020;17(6): 2141. 10.3390/ijerph17062141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ziadni M. S., Jasinski M. J., Labouvie-Vief G., & Lumley M. A. (2017). Alexithymia, defenses, and ego strength: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with psychological well-being and depression. Journal of happiness studies, 18(6), 1799–1813. 10.1007/s10902-016-9800-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gori A, Craparo G, Caretti V, Giannini M, Iraci-Sareri G, Bruschi A, et al. Impulsivity, alexithymia and dissociation among pathological gamblers in different therapeutic settings: A multisample comparison study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246: 789–795. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Craparo G, Gori A, Dell’Aera S, Costanzo G, Fasciano S, Tomasello A, et al. Impaired emotion recognition is linked to alexithymia in heroin addicts. PeerJ, 2016;4: e1864. 10.7717/peerj.1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pellerone M, Cascio MI, Costanzo G, Gori A, Pace U, Craparo G. Alexithymia and psychological symptomatology: research conducted on a non-clinical group of Italian adolescents. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health, 2017;10(3): 300–309. 10.1080/17542863.2017.1307434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data files are available from the Figshare database (doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.14139944).