Abstract

In-law relationships can act as sources of both support and stress for couples. Independent of the nature of the actual relationships with in-laws, it may be that couple similarity in perceptions of these ties determines if they undermine or facilitate marital stability. The current study sought to examine how spousal connections to in-laws and concordance about these relationships early in marriage predicted marital stability in a sample of 355 Black and White married couples followed over 16 years. Husbands and wives reported on time spent with families, whose family they turn to for support, and closeness with families during their first year of marriage. Analyses revealed that discordance on these issues early in marriage was common. We found that even after controlling for husband and wife reports of connections with in-laws, discordance on closeness with the wife’s family predicted divorce. Thus, when conceptualizing the costs and benefits of connections with in-laws, it is important to consider not only the nature of spouses’ ties to each other’s families, but the extent to which their views of these ties are concordant.

Keywords: concordance, consensus, marital stability, in-laws

Spouses who are similar across a variety of indices (e.g., personality, values, health) generally enjoy more satisfying and stable relationships (Gaunt, 2006; Gonzaga, Campos, & Bradbury, 2007). In particular, spouses who hold similar beliefs about issues typically associated with relationship quality (e.g., the division of household labor; Hohmann-Marriott, 2006) or who hold similar perceptions about their relationship itself (e.g., how stable their relationship is; Wilson & Huston, 2013) are more likely to stay together. Being on the same page as a couple may be especially beneficial when navigating in-law ties, as those ties are often challenging (Bryant, Conger, & Meehan, 2001; Orbuch, Bauermeister, Brown, & McKinley, 2013; Silverstein, 1990). However, very little is known about how concordance or consensus about in-law ties (e.g., agreement about closeness to each other’s families of origin) is related to relationship outcomes, and if it provides unique leverage to understand marital outcomes above and beyond those provided by the relationship indicators themselves (e.g., closeness to in-laws). Thus, the purpose of the present study is to compare how connections to in-laws and discordance about these relationships predict risk of divorce among among Black and White married couples followed over the first 16 years of their marriage.

Spouses’ Connections to their In-Laws

Couples often report that relationships with in-laws are one of their biggest sources of conflict (Williamson et al., 2013). Indeed, acrimonious relationships with in-laws have been found to undermine the marital relationship (Bryant et al., 2001; Fingerman et al., 2012; Orbuch et al., 2013; Silverstein, 1990). At the same time, however, in-law relationships characterized by greater support and better relationship quality can be some of individuals’ closest ties (Santos & Levitt, 2007). But even closeness may put couples at risk if it is unbalanced across families of origin. For example, couples appear to be at elevated risk for poorer marital quality if they are in networks characterized by greater closeness to the wives’ family (Fiori et al., 2017).

Perhaps not surprisingly in light of women’s greater involvement in families stemming from traditional kin-keeping roles (Leach & Braithwaite, 1996; Rittenour, 2012), there appear to be gender differences in spouses’ connections to their in-laws and how these are linked to their marital outcomes. For example, women are more likely to turn to their own families than their in-laws, whereas men do not appear to show a preference (Lee, Spitze, & Logan, 2003; Marx, Miller, & Huffmon, 2011). Perhaps as a result, wives are more likely to have conflictual relationships with their in-laws than are men (Rittenour, 2012; Silverstein, 1990). As to potential gender differences in the links between in-law ties and marital outcomes, Bryant and colleagues (2001) found in a longitudinal study of rural White families that conflict with in-laws predicted poorer perceptions of marital success for both husbands and wives. However, wife’s reported discord with her in-laws was a stronger predictor of both her own and her husband’s perceptions of marital success. Indeed, networks characterized by closeness to both families appeared to yield more uniform benefits, suggesting that not only are the associations different for husbands and wives, but the associations may vary based on whose family is considered and the overall balance (e.g., of time spent) between families.

The Role of Consensus in Relationship Outcomes

Research on concordance shows that spouses who agree on a variety of issues, particularly those focused on their relationship itself (e.g., division of household labor, relationship stability; Hohmann-Marriott, 2006; Wilson & Huston, 2013), are more likely to stay together. In fact, premarital couples who lack what some researchers have called a ‘shared reality’ are at a greater risk of divorce once they do marry, even after controlling for mean levels of love (Wilson & Huston, 2013). Similarly, Buehlman, Gottman, and Katz (1992) found that using language indicative of a collective identity was associated with a lower incidence of divorce three years later in a sample of married couples with children. Furthermore, partner agreement on relationship problems has actually been linked to more successful treatment outcomes for couples who enter therapy (Biesen & Doss, 2013). Interestingly, although Gager and Sanchez (2003) found that time spent together seemed to buffer against divorce, couples who agreed that they spent little time together were no more likely to divorce than couples who agreed that they spent time together daily. This implies that consensus on relationship events and issues may sometimes be just as - if not more - important than the issues or events themselves.

Moreover, consensus on certain relationship events and issues may be more important for couples’ functioning than consensus on other topics. In light of the aforementioned challenges of in-law relationships (Bryant et al., 2001; Fingerman et al., 2012; Orbuch et al., 2013; Williamson et al., 2013), how might consensus about in-laws be associated with marital outcomes? It may be that spouses disagreeing about their connections to their in-laws could exacerbate challenges within these relationships. Conversely, difficult relationships with in-laws could be less detrimental to the marriage if both spouses are on the same page about those relationships, suggesting that the consensus perspective may be a useful lens through which to understand in-law relationships and their effects on marriage. Supporting this perspective is work from Pasley, Ihinger-Tallman, and Coleman (1984) showing that happy couples tended to agree more than unhappy couples on their perceptions of conflict over family-related issues. Moreover, disagreements about the role of extended family in a couple’s life (e.g., filial obligation) predicts lower marital satisfaction, at least for husbands (Polenick et al., 2017). In addition, Silverstein (1990) suggested that connections with in-laws may be particularly prone to issues of discordance between spouses, as even differences in preferences about which family couples should spend their time with during the holidays can lead to marital conflict. However, as she noted, “[w]hen spouses have good communication and are empathic allies with each other, the pain about families of origin can bring them closer” (p. 406).

Consistent with this sentiment, perhaps the most compelling evidence in support of the importance of consensus is that couples even benefit from agreeing about problematic in-law relationships. For example, Rittenour and Kellas (2015) found that couples who agreed about conflict with the husband’s mother (e.g., mother-in-law’s motives for hurtful comments) were more satisfied than couples in which spouses differed in their attributions of hurtful behavior. However, we are not aware of any studies to date that specifically examine consensus on perceptions of in-law relationships more broadly (e.g., closeness to families and time spent with families), nor of work that considers whether or not couples characterized by greater discordance on these variables are at an elevated risk of divorce. Given the benefits of similarity (Gaunt, 2006), conceivably, couples with more discordance on their perceptions of in-law relationships should be more likely to divorce over time than those with more agreement.

The Present Study

Social capital theory implies that marriage should benefit couples because of the increase in social resources that comes with combining two separate social networks (Acock & Demo, 1994; Curran et al., 2003). Although connections with families should be a net benefit, given that they represent additional resources, ties to in-laws are often characterized as sources of stress. In fact, acrimonious relations with in-laws can undermine couples’ functioning (Bryant et al., 2001; Orbuch et al., 2013; Silverstein, 1990). Given the benefits of spousal similarity on other aspects of their lives (Gaunt, 2006; Gonzaga et al., 2007; Wilson & Huston, 2013), similarity of couples’ views on each other’s families may perhaps be a stronger predictor of divorce than their actual reported relationships with the in-laws. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine the role of discordance in husband and wife perceptions of the balance of time spent with each other’s families, which family is the primary source of support, and closeness with each other’s families, in predicting the risk of divorce, controlling for actual levels of these variables. We hypothesized that discordance on each of these variables would be linked to an increased risk of divorce 16 years later. Moreover, we sought to investigate the extent to which there was a cumulative effect of this early discordance on divorce; that is, we predicted that more sources of discordance early in marriage would be linked to a greater risk of divorce 16 years later.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The Early Years of Marriage Project (EYM; for additional information about the study design and participants, please see Orbuch & Veroff (2002) or the project website at http://projects.isr.umich.edu/eym/) is a longitudinal panel study started in 1986 following 373 couples who applied for marriage licenses in Wayne County, MI, across the first 16 years of marriage. This study was one of the first to examine marriages over time and unique in its focus on exploring marital processes in both Black couples and White couples. To ensure adequate power in the longitudinal data to compare Black and White couples, the investigators both oversampled for Black couples and focused exclusively on same-race couples. Specifically, data were collected from 174 White and 199 Black couples in first marriages. Couples were eligible for the study if they were same-race couples entering into their first marriage, and if the wife was younger than 35. When comparing the EYM sample to a nationally representative sample of Black and White newlywed individuals in the General Social Survey (GSS), there were no significant differences by race in income, education, parental status, cohabitation, employment, or other sociodemographic factors (Orbuch, Veroff, Hassan, & Horrocks, 2002).

Face-to-face individual interviews were conducted in participants’ homes with interviewers in Years 1, 3, 7, and 16 of the study. Interviewers were matched to couples by race to reduce attrition and ensure a higher response rate (see Frierson et al., 2019). Information about divorce for each couple (i.e., whether or not they had divorced and when) was obtained in each of these years. To note, both members of the couple were retained in the study regardless of marital status. Extensive tracking efforts and telephone interviews in Years 14 and 16 provided more precise estimates of which respondents divorced during the 16 years. By Year 16, 46.1% (n = 172) of the couples had separated or divorced, including 63 of the original 174 White couples (36.2%) and 109 of the original 199 Black couples (54.8%).

At Year 1, husbands averaged 26.48 years of age (SD = 4.15) and wives averaged 24.31 years of age (SD = 3.88). Husbands’ mean number of years of education was 13.11 (SD = 1.92), and wives’ was 13.13 (SD = 1.89) (with a range from 8 to 17 years). Average income at Year 1 was $30,933 (SD = $16,864), with a range from $1,500 to $80,000. Approximately 55% of the Black American couples and 23% of the White American couples entered the marriage with at least one child. About 30% of the wives (24% White American; 36% Black American) and 21% of the husbands (12% White American; 29% Black American) had parents who divorced when the respondent was young (under 16). See Table 1 for differences in study variables by race and Year 16 marital status.

Table 1.

Overall Descriptives and Race Differences on All Year 1 Study Variables

| Variables | Overall M (SD)/% |

White M (SD)/% |

Black M (SD)/% |

t or χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black | 53% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Year 16 Divorced | 48% | 37% | 59% | 17.80** |

| Income (in $K) | 30.93 (16.86) | 35.92 (17.06) | 26.55 (15.45) | 5.53** |

| Wife education | 13.12 (1.89) | 13.04 (1.99) | 13.20 (1.79) | −0.83 |

| Husband education | 13.11 (1.92) | 13.33 (1.97) | 12.92 (1.86) | 2.09* |

| Wife’s parents divorced | 30% | 24% | 37% | 7.73** |

| Husband’s parents divorced | 21% | 12% | 30% | 16.90** |

| Child before marriage | 40% | 22% | 55% | 40.62** |

| Which family more time spent (wife report) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2.11 |

| Which family more time spent (husband report) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 6.77† |

| Which family to call on (wife report) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 9.57* |

| Which family to call on (husband report) | n/a | n/a | n/a | 16.96** |

| Wife report of husband’s closeness to her family | 3.24 (0.72) | 3.23 (0.73) | 3.25 (0.71) | −0.20 |

| Husband report of his closeness to wife’s family | 3.26 (0.71) | 3.23 (0.71) | 3.20 (0.70) | 1.66† |

| Husband report of wife’s closeness to his family | 3.29 (0.73) | 3.29 (0.71) | 3.28 (0.75) | 0.08 |

| Wife report of her closeness to husband’s family | 3.14 (0.84) | 3.23 (0.84) | 3.07 (0.84) | 1.84† |

| % agree with which family more time spent | 58% | 62% | 56% | 1.62 |

| % agree which family to call on for advice/support | 42% | 51% | 35% | 10.03** |

| % agree closeness to husband’s family | 86% | 90% | 83% | 4.20* |

| % agree closeness to wife’s family | 84% | 86% | 82% | 0.94 |

| Total family discordance | 1.28 (0.93) | 1.11 (0.88) | 1.43 (0.94) | −3.39** |

Note.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

SD = Standard Deviation. All discordance variables are dichotomous.

In the present analyses we include only those 355 couples for whom divorce information was available, since we are predicting divorce as our primary outcome. The 18 couples who were missing divorce information (i.e., neither member of the couple reported whether or not they had divorced) had significantly lower income, were more likely to be Black, and were more likely to have a child before marriage than the remaining 355 couples with complete information. In addition, among the 18 couples with missing data, both husbands and wives were significantly older and husbands’ parents were more likely to have divorced when he was a child.

Measures

Divorce.

Divorce was coded as a dichotomous variable (where 0 = not divorced and 1 = divorced), and included any case of divorce across the 16-year period. Marital duration (in years) was used as the time-varying censored dependent variable, allowing us to examine time to divorce.

Discordance in in-law relationships.

Discordance between spouses on their in-law relationships was assessed by comparing spouses’ reports at Year 1 across four different indicators.

Discordance in time spent with families.

At Year 1, respondents were asked, “As a couple, would you say you spend: more time with your own family, more time with your (wife’s/husband’s) family, about the same amount of time with both, or no time with either?” From this variable, we created a categorical ‘time spent’ discordance variable, in which couples were categorized as agreeing or disagreeing on the original variable. As shown in Table 2, there were four ‘types’ of agreement/concordance and six types of disagreement/discordance. We then created a dichotomous version of the variable that we used as our primary ‘concordance on time spent with families’ variable (also shown in Table 2).

Table 2.

Categorical and Dichotomous Versions of Discordance on Family Contact Variables

| Categorical ‘Time Spent’ Concordance | Categorical ‘Who to Call On’ Discordance | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Agree wife focused | 100 (27%) | 30 (8%) |

| Agree husband focused | 53 (14%) | 33 (9%) |

| Agree balanced | 64 (17%) | 89 (24%) |

| Both agree ‘neither’ | 1 (.3%) | 42 (11%) |

| One spouse says ‘neither’ | 18 (5%) | 31 (8%) |

| Disagree on which spouse’s family | 24 (6%) | 49 (13%) |

| Wife says balanced, husband says husband focused | 41 (11%) | 8 (2%) |

| Wife says balanced, husband says wife focused | 21 (6%) | 16 (4%) |

| Husband says balanced, wife says husband focused | 22 (6%) | 67 (18%) |

| Husband says balanced, wife says wife focused | 28 (8%) | 5 (1%) |

| Dichotomous ‘Time Spent’ n (%) Concordance |

Dichotomous ‘Who to Call On’ Discordance n (%) | |

| Agree | 218 (58%) | 157 (42%) |

| Disagree | 155 (42%) | 213 (58%) |

Discordance in which family to call on for advice/help.

Respondents were also asked at Year 1, “As a couple, whose family would you call on for advice or help if you needed it - your own family, your (wife’s/husband’s) family, each family about equally, or neither family?” From this variable, we created a categorical ‘who to call on for advice/help’ concordance variable, in which couples were categorized as agreeing or disagreeing on the original variable. As shown in Table 2 and paralleling the ‘time spent’ variable, there were four ‘types’ of agreement/ concordance and six types of disagreement/discordance. As shown in Table 2, we then created a dichotomous version of the variable that we used as our primary ‘concordance on which family to call on’ variable.

Discordance in closeness to husbands’ and wives’ families.

Also at Year 1, respondents were asked to answer the following questions on a scale from 1 (not at all close) to 4 (very close): “How close do you think your (wife/husband) feels to your family?”; and “How close do you feel to your (wife’s/husband’s) family?” From these two questions, we created two new variables: Discordance on wife’s closeness to husband’s family; and Discordance on husband’s closeness to wife’s family. We defined ‘agreement’ as both spouses responding with either a 1 or a 2, or with a 3 or a 4, on the items corresponding to a particular family (husband’s or wife’s). ‘Disagreement’ was then defined as one spouse responding with a 1 or a 2, and the other spouse responding with a 3 or a 4. As shown in Table 3, there were two types of agreement/concordance and two types of disagreement/discordance. We then collapsed into dichotomous ‘agree/disagree’ variables for use as our primary ‘discordance on closeness to husband’s family’ and ‘discordance on closeness to wife’s family’ variables (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Categorical and Dichotomous Versions of Discordance on Closeness to Families Variables

| Categorical ‘Closeness to Husband’s Family’ Discordance | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Both spouses agree wife is not close to husband’s family | 35 (9%) |

| Both spouses agree wife is close to husband’s family | 285 (77%) |

| Husband thinks wife is not close to his family, but she thinks she is close | 16 (4%) |

| Husband thinks wife is close to his family, but she thinks she is not close | 35 (9%) |

| Dichotomous ‘Closeness to Husband’s Family’ Discordance | n (%) |

| Agree | 320 (86%) |

| Disagree | 51 (14%) |

| Categorical ‘Closeness to Wife’s Family Discordance | n (%) |

| Both spouses agree husband is not close to wife’s family | 12 (3%) |

| Both spouses agree husband is close to wife’s family | 298 (80%) |

| Wife thinks husband is not close to her family, but he thinks he is close | 36 (10%) |

| Wife thinks husband is close to her family, but he thinks he is not close | 25 (7%) |

| Dichotomous ‘Closeness to Wife’s Family’ Discordance | n (%) |

| Agree | 310 (84%) |

| Disagree | 61 (16%) |

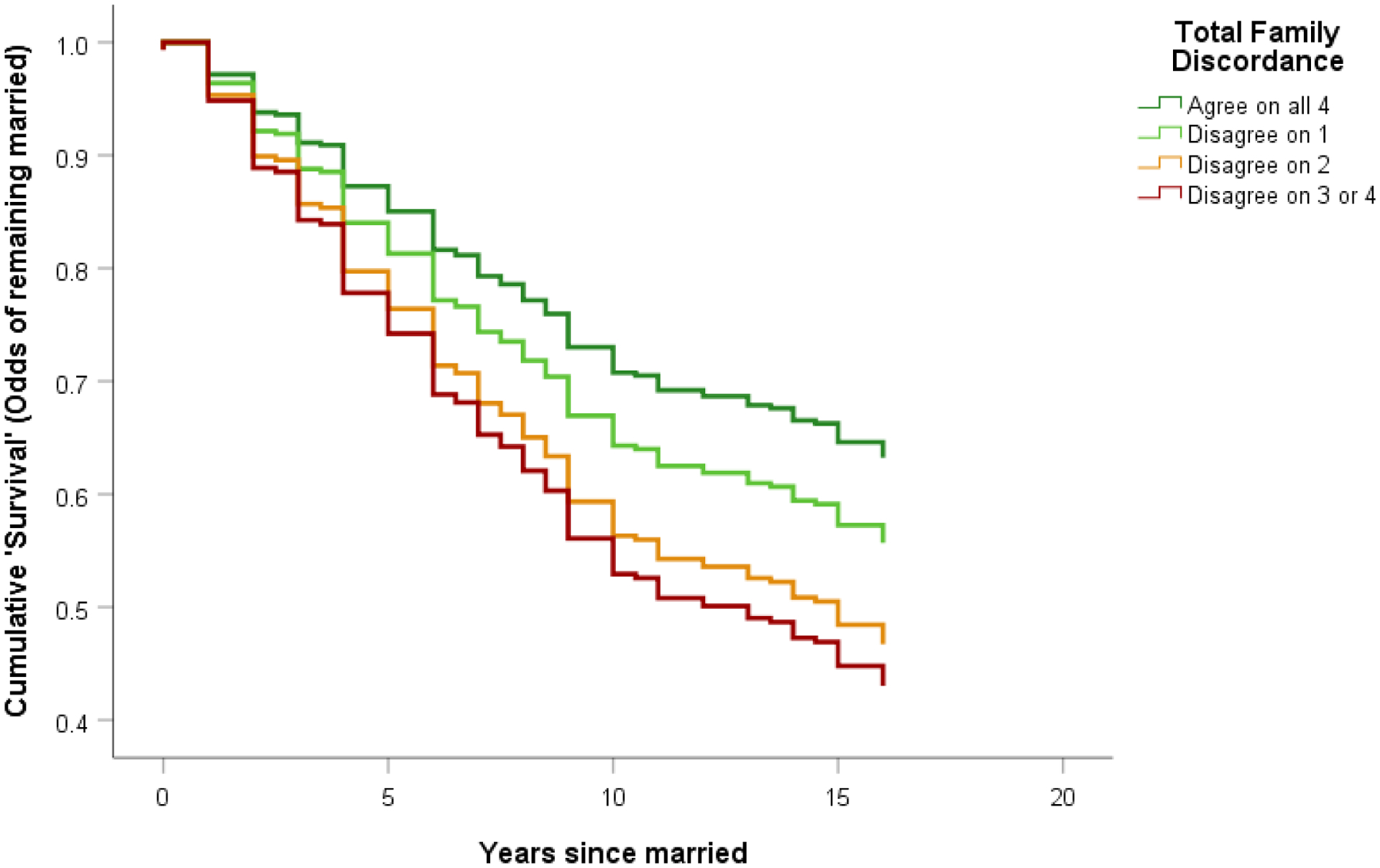

Total family discordance.

To capture overall levels of family discordance, we created a ‘total family discordance’ variable in which we summed the four dichotomous agree (0)/disagree (1) discordance variables. We collapsed across the values 3 and 4, because so few couples disagreed on all variables (i.e., scored a ‘4’; n = 5), such that scores ranged from 0 (agree on all 4) to 3 (disagree on 3 or 4). To note, correlations among the dichotomous discordance variables were quite low (ranging from −.003 to .147), suggesting that they were in fact tapping into distinct aspects of couples’ connections with family.

Covariates.

In addition to controlling for the indicators of the in-law relationships themselves (e.g., time spent on families, whose family to call on for advice/help, closeness to husbands’ and wives’ families), several demographic factors were also covaried because of their associations with divorce (Orbuch et al., 2002; Orbuch et al., 2013; Timmer & Veroff, 2000). Race of the couple was operationalized as White American (0) or Black American (1). For Household income, respondents selected from income categories for the entire household before taxes. The response was then coded as the midpoint of the category selected, and divided by 10,000 so that unstandardized survival parameter estimates would not round to zero. Husband education and Wife education were operationalized as the total number of years of schooling completed by Year 1. Husband parents’ marital status and Wife parents’ marital status identified those respondents whose parents had divorced prior to age 16 (0 = Married household, 1 = Parents divorced before respondent was 16 years old). Finally, Child before marriage was created to reflect whether or not the wife had no child before marriage (0) or had a child or was pregnant before marriage (1).

Results

Do Couples Agree about their Families Early in their Marriages?

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the full sample, as well as separately for Black and White couples. As seen in Table 1, a total of 218 couples (58%) agreed on the balance of time spent with their families, whereas 155 couples (42%) disagreed. A total of 157 couples (42%) agreed on whose family to call on for advice/help, whereas 213 couples (58%) disagreed Furthermore, 320 couples (86%) agreed on the wife’s closeness to the husband’s family, whereas 51 (14%) of couples disagreed (see Table 1). Similarly, 310 couples (84%) agreed on the husband’s closeness to the wife’s family, whereas 61 (16%) disagreed. For total family discordance, whereas 81 couples (22%) agreed on all 4 family variables, the majority disagreed on at least one (n = 142, 39%) or two (n = 106, 29%). Thirty-nine couples (11%) disagreed on 3 or 4 variables.

Does Discordance in In-Laws Predict Divorce?

In order to test if discordance on in-laws would predict divorce, we ran four hierarchical Cox (proportional hazard) regressions, with divorce at Year 16 as the outcome and marital duration as the time-varying censored dependent variable. The advantage of this type of analytic approach is that it allows for full use of the data, in spite of variations in both whether or not couples divorced and the timing of the divorce (Orbuch et al., 2002). For each regression, we included covariates in the first step; in the second step we added the measures of actual connections to families in Year 1 (either both spouses’ reports of time spent with families, which family to call on for support/advice, or closeness to in-laws); and in the final step, we added the discordance variables on the indicator of family connections.

In the first Cox regression, we tested discordance on time spent with families as a predictor of divorce over time. Among the covariates included in Step 1, only race (HR = 1.92, p < .001) and wife’s education (HR = 0.83, p = .001) were significant predictors (see Table 4). The addition of the variables regarding actual husband and wife reports of time spent with families in Step 2 did not add a significant amount of variance to the model. In Step 3, the ‘time spent’ discordance variable was nearing significance as a predictor of divorce (HR = 0.74, p = .058). The second Cox regression examined discordance on who couples called on for advice as a predictor of divorce. This indicator did not yield any significant main effects.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Cox Regression Predicting Divorce across Years 1 through 16 from Discordance on ‘Time Spent with Families’

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Race | 1.92*** | 1.35–2.73 | 1.97*** | 1.38–2.81 | 1.94*** | 1.36–2.77 | 1.55 | 0.51–4.71 |

| Household income (1986) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Wife education | 0.83** | 0.74–0.93 | 0.82** | 0.73–0.92 | 0.83** | 0.74–0.93 | 0.82*** | 0.73–0.92 |

| Husband education | 0.93 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.94 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.02 |

| Wife’s parents divorced | 1.20 | 0.86–1.68 | 1.26 | 0.90–1.78 | 1.27 | 0.90–1.78 | 1.30 | 0.92–1.83 |

| Husband’s parents divorced | 0.94 | 0.64–1.40 | 0.92 | 0.62–1.37 | 0.91 | 0.61–1.35 | 0.91 | 0.61–1.35 |

| Child(ren) before marriage | 1.04 | 0.74–1.47 | 1.02 | 0.72–1.45 | 1.05 | 0.74–1.48 | 1.02 | 0.72–1.45 |

| Time spent wife report | 0.87 | 0.73–1.04 | 0.85† | 0.71–1.01 | 1.38 | 0.74–2.55 | ||

| Time spent husband report | 1.15 | 0.96–1.38 | 1.14 | 0.95–1.36 | 0.54† | 0.28–1.04 | ||

| Discordance on time spent | 0.74† | 0.54–1.01 | 0.48 | 0.16–1.44 | ||||

Note.

p < .10,

p < .01,

p < .001;

HR = Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

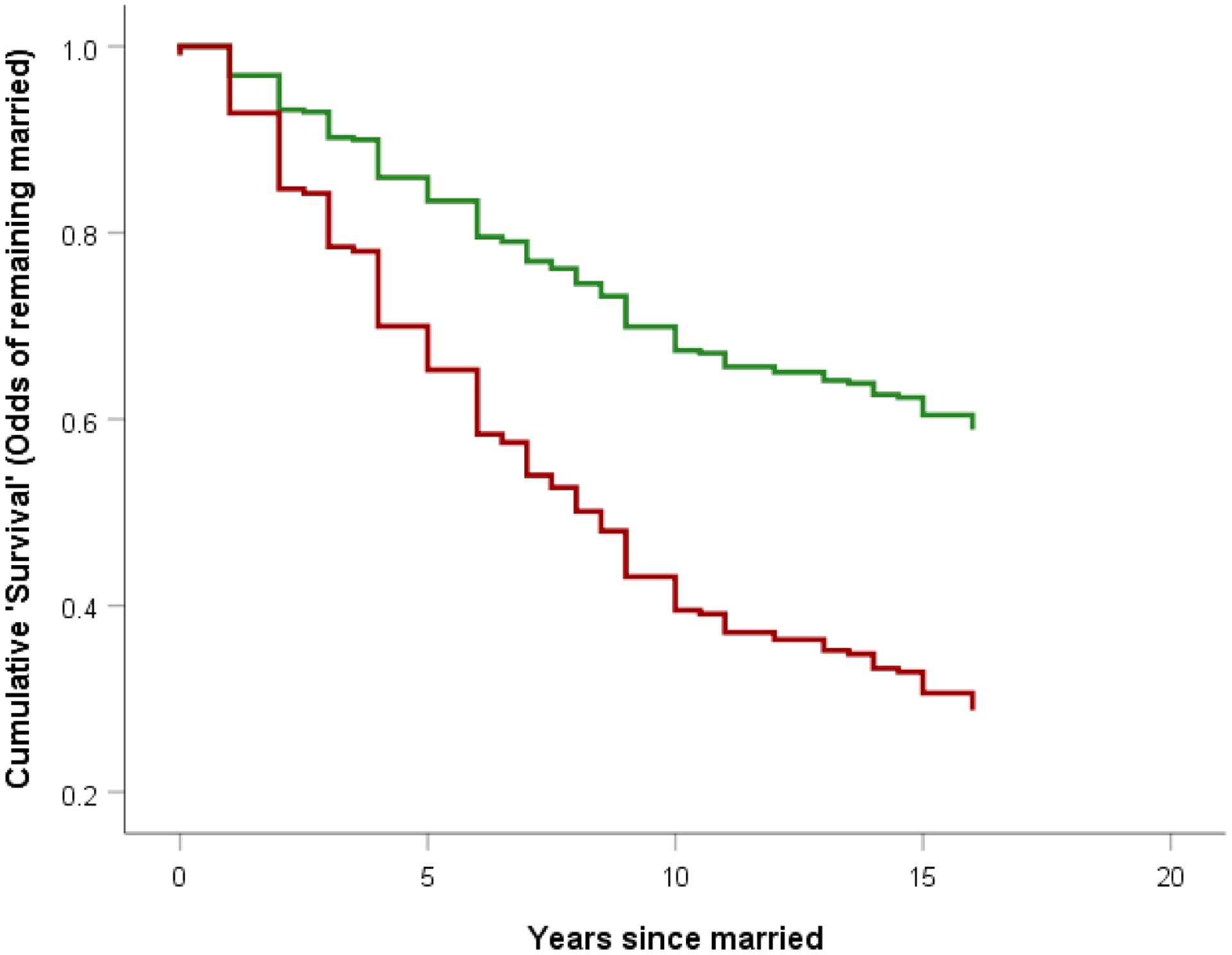

The third Cox regression predicted divorce as a function of discordance on closeness to the wife’s family (see Table 5), controlling for background variables. Husband and wife reports of closeness were not a significant predictor in Step 2. However, in Step 3, controlling for these indicators, discordance was a significant predictor of divorce (HR = 0.54, p = .009). As seen in Figure 1, couples who agreed about the husband’s closeness to his wife’s family were significantly less likely to divorce across the 16 years than those who disagreed. In interpreting Figure 1, it should be noted that this effect appears to be driven primarily by those couples in which the wife thinks the husband is not close to her family, but he thinks he is (n = 36; see Table 3). In fact, of those 36 couples, 26 were divorced by Year 16, translating to a 72% divorce rate. In contrast, the rate of divorce for the 25 couples in which the wife thinks the husband is close to her family, but he thinks he is not (48%), was similar to the rate for the overall sample (46%). Our fourth regression revealed that discordance on closeness to the husband’s family was not a significant predictor of divorce.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Cox Regression Predicting Divorce across Years 1 through 16 from Discordance on Closeness to Wife’s Family

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Race | 1.90*** | 1.34–2.71 | 1.92*** | 1.35–2.74 | 1.93*** | 1.36–2.76 | 6.26 | 0.69–56.88 |

| Household income (1986) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Wife education | 0.83** | 0.74–0.93 | 0.83** | 0.74–0.93 | 0.82** | 0.73–0.92 | 0.82** | 0.74–0.92 |

| Husband education | 0.93 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.02 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.02 | 0.92 | 0.84–1.02 |

| Wife’s parents divorced | 1.20 | 0.86–1.68 | 1.17 | 0.83–1.64 | 1.11 | 0.78–1.56 | 1.10 | 0.78–1.56 |

| Husband’s parents divorced | 0.94 | 0.64–1.40 | 0.91 | 0.61–1.36 | 0.91 | 0.61–1.36 | 0.91 | 0.60–1.36 |

| Child(ren) before marriage | 1.03 | 0.73–1.46 | 1.01 | 0.72–1.44 | 0.99 | 0.70–1.40 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.42 |

| Wife’s report of husband’s closeness to her family | 0.95 | 0.73–1.24 | 1.08 | 0.82–1.41 | 1.58 | 0.61–4.08 | ||

| Husband’s report of closeness to wife’s family | 0.92 | 0.71–1.18 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.26 | 1.13 | 0.45–2.82 | ||

| Discordance on closeness to wife’s family | 0.54** | 0.34–0.85 | 0.28 | 0.05–1.48 | ||||

Note.

p < .10,

p < .01,

p < .001;

HR = Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Figure 1.

‘Survival’ curves (odds of remaining married) in which the couples either disagree (red) or agree (green) about the husband’s closeness to the wife’s family.

In the final Cox regression model, we tested if ‘total family discordance’ predicted divorce, controlling for husband and wife reports on all of the in-law relationship variables. As shown in Step 3 of Table 6, total family discordance was nearing significance as a predictor of divorce (HR = 1.20, p = .059). As seen in Figure 2, with increasing discordance, couples were more likely to divorce across the 16 years.

Table 6.

Hierarchical Cox Regression Predicting Divorce across Years 1 through 16 from Total Family Discordance

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Race | 1.91*** | 1.34–2.73 | 2.00*** | 1.40–2.86 | 1.92*** | 1.34–2.75 | 1.85* | 1.00–3.40 |

| Household income (1986) | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Wife education | 0.82** | 0.74–0.92 | 0.82** | 0.73–0.92 | 0.82** | 0.73–0.92 | 0.82** | 0.73–0.92 |

| Husband education | 0.93 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.93 | 0.85–1.03 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.02 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.03 |

| Wife’s parents divorced | 1.20 | 0.86–1.68 | 1.21 | 0.85–1.71 | 1.18 | 0.84–1.67 | 1.19 | 0.84–1.69 |

| Husband’s parents divorced | 0.94 | 0.64–1.40 | 0.85 | 0.57–1.28 | 0.86 | 0.57–1.29 | 0.86 | 0.57–1.29 |

| Child(ren) before marriage | 1.04 | 0.74–1.47 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.43 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.44 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.44 |

| Time spent wife report | 0.88 | 0.72–1.06 | 0.86 | 0.72–1.04 | 0.86 | 0.71–1.04 | ||

| Time spent husband report | 1.18† | 0.98–1.41 | 1.15 | 0.95–1.38 | 1.15 | 0.95–1.38 | ||

| Call on wife report | 0.93 | 0.78–1.11 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | 0.97 | 0.82–1.17 | ||

| Call on husband report | 0.98 | 0.84–1.15 | 0.99 | 0.84–1.16 | 0.99 | 0.84–1.16 | ||

| Wife’s report of husband’s closeness to her family | 0.94 | 0.72–1.23 | 0.99 | 0.75–1.30 | 0.99 | 0.75–1.31 | ||

| Husband’s report of closeness to wife’s family | 0.86 | 0.66–1.13 | 0.88 | 0.67–1.14 | 0.88 | 0.67–1.14 | ||

| Husband’s report of wife’s closeness to his family | 1.12 | 0.84–1.48 | 1.09 | 0.83–1.44 | 1.09 | 0.83–1.44 | ||

| Wife’s report of closeness to husband’s family | 0.89 | 0.70–1.14 | 0.93 | 0.73–1.19 | 0.93 | 0.73–1.19 | ||

| Total family discordance | 1.20† | 0.99–1.44 | 1.14 | 0.63–2.08 | ||||

Note.

p < .10,

p < .01,

p < .001;

HR = Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval

Figure 2.

‘Survival’ curves (odds of remaining married) in which the couples either agree on all 4 discordance variables (dark green), disagree on 1 (light green), disagree on 2 (orange), or disagree on 3 or 4 (red).

Discussion

Although the merging of two separate social networks that occurs when individuals marry is thought to provide both spouses with greater social resources (e.g., more support; Acock & Demo, 1994), it is not always a smooth process. Most notably, acrimonious relationships with in-laws have been found to undermine the marital relationship (Bryant et al., 2001; Fingerman et al., 2012; Orbuch et al., 2013), although these relationships can be important sources of support for some individuals (Santos & Levitt, 2007). Perhaps more notably, when spouses agree about in-laws, they may derive benefits from these shared spousal perceptions (Rittenour & Kellas, 2017), regardless of the dynamics of the relationships themselves. The purpose of the present study was to explore if discordance in couples’ perceptions of in-laws would predict divorce amongBlack and White married couples followed over the first 16 years of their marriage.

Connections to In-Laws: Are Couples on the Same Page and Does Concordance Matter?

Although previous research has suggested that direct connections with in-laws can be sources of support or strain (Bryant et al., 2001; Orbuch et al., 2013; Santos & Levitt, 2007), neither husbands’ nor wives’ own reports of connections with in-laws (i.e., time spent, family called on for support, and closeness) predicted the likelihood of divorce over time in our analyses. Given that previous research has focused more specifically on actual discord within the in-law relationship (Bryant et al., 2001; Orbuch et al., 2013), our focus on more structural variables (e.g., time spent with families) may have minimized links between issues in these areas and marital stability. For example, it could be that spending time with in-laws in and of itself is not problematic unless that time is characterized by greater tension and negativity (Morr Serewicz & Canary, 2008). Furthermore, our analyses suggest that what might be key for couples is if they view these ties similarly (i.e., concordance).

In fact, our descriptive analyses indicated that spouses often do not agree on the dynamics of their relationships with each other’s families of origin. Although a small percentage of couples disagreed about how close they are to each other’s families, about half of the couples disagreed on which family they spend more time with or which family they would call on for advice. Furthermore, although fewer couples disagreed about how close they are to each other’s families, these disagreements appeared to be more damaging to the marriage. Analyses revealed that discordance related to husband’s closeness to the wife’s family significantly predicted divorce, even after controlling for husband and wife reports of levels of closeness. Interestingly, and as explained in the results, it appears that it is those couples in which the wife thinks the husband is not close to her family, but he thinks he is, that are at greatest risk of divorce, with a 72% divorce rate. In contrast, the rate of divorce for couples in which the wife thinks the husband is close to her family, but he thinks he is not, was only 48%.

These results are particularly interesting given that Orbuch et al. (2013) found that when a husband reported feeling close to the wife’s family early in the marriage, that actually reduced the odds of divorce over time for the couple. Our results show that whether or not the husband is close to the wife’s family seems less important than whether or not the spouses agree that the husband is or is not close. Such discrepancies are perhaps not surprising, in light of work demonstrating that relationships with in-laws are often a source of conflict for couples (Papp, 2018; Williamson et al., 2013). Perhaps part of this conflict may be explained by the fact that couples do not appear to see eye-to-eye on how connected they are with each other’s families. For example, the finding that couples were more likely to divorce if husbands viewed themselves as close to their in-laws, but wives felt this was not the case, may be explained by Papp’s (2018) work suggesting that wives were more likely than husbands to bring up issues concerning their relatives. If these discrepancies do in fact translate into increased conflict on these topics warrants further investigation, as how spouses discuss and respond to each other when discrepancies arise can influence relational outcomes (Morr Serewicz & Canary, 2008; Morr Serewicz et al., 2008).

It is important to note that the cumulative effect of these disagreements on the risk of divorce neared significance. That is, it appears that the number of disagreements at Year 1 accounted for marital instability even though not all of the individual discordance variables themselves were predictive. Controlling for both spouses’ actual reports of family balance and closeness, those couples with more disagreements about in-laws were more likely to experience divorce than those with fewer disagreements. Greater similarity tends to predict higher marital satisfaction (Gaunt, 2006), suggesting that having greater dissimilarity - as is the case with our total family discordance - would put the couples at an increased risk of marital issues. As to how this would happen, Gaunt (2006) suggests that having greater discrepancies in areas of importance to the couple may create more marital conflict and feelings of negativity and resentment. As the accumulation of negativity is deleterious for marital functioning (Gottman, 2014; Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001), future work should examine conflict and satisfaction as potential mechanisms underlying the links found here.

Considerations and Conclusions

Despite numerous strengths of our study, including the longitudinal, dyadic approach with a diverse sample of newlyweds, there are some considerations for future research. First, although we were able to examine multiple dimensions of in-law relationships (e.g., closeness, time spent), couples’ individual and shared perceptions regarding more specific in-law interactions may be more closely linked to marital outcomes. For example, Rittenour and Kellas (2017) found that perceived similarity in partner’s attributions for in-laws’ behaviors positively predicted marital satisfaction, underscoring the importance of couples’ shared perceptions of more proximal indicators of in-law relationships. Second, given previous research indicating that couples are more likely to divorce when partners dislike each other’s friends (Fiori et al., 2018), future work should consider if concordance regarding couples’ friend networks plays a similar role in marital stability as family concordance. Moreover, given that couples are embedded in networks comprised of both families and friends (Fiori et al., 2017), examining concordance about the network as a whole may better elucidate how shared perceptions of social resources predict marital outcomes. Third, it is unclear if couples are aware of the amount of discordance that exists in their connections to their network members. The links between discordance and marital stability may be somewhat mitigated for couples who perceive their relationship as more concordant than it actually is, as perceptions of similarity may be more beneficial to couples than actual similarity (Acitelli, Douvan, & Veroff, 1993). Finally, the processes by which discordance predicts divorce warrants further investigation (e.g., disruption of communication routines; Prentice, 2008)).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates the importance of concordance regarding in-law relationships. It is noteworthy that agreement between couples, particularly on closeness with the wife’s family, was more predictive of marital stability than the husband and wife reports of actual levels of closeness. Such information could be useful from a therapeutic standpoint, as very often influences on contact and closeness with in-laws are outside of couples’ control (e.g., physical distance). A ‘shared reality’ (Wilson & Huston, 2013) of not just the romantic relationship itself, but also of the relationships surrounding the couple, may help couples navigate challenges that may otherwise interfere in the longevity of their marriage. Moreover, even small, incremental changes in shared perceptions, such as helping couples see eye-to-eye on a single issue related to in-laws, may be beneficial, given our findings suggesting that the accumulation of discordance may be problematic. Thus, tensions associated with in-law relationships, traditionally thought to be one of the most fraught ties in an individual’s social network (Bryant et al., 2001; Orbuch et al., 2013; Rittenour & Kellas, 2015), may be more manageable than previously believed. In fact, seemingly intractable issues that have traditionally been attributed to in-laws may instead be capturing couple communication dynamics that can - and should - be modified to promote couples’ long-term relationship success and stability.

Acknowledgments

The research in this article was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant HD40778) to the fifth author, TLO. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the third author, KSB, upon reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Katherine L. Fiori, Adelphi University.

Amy J. Rauer, University of Tennessee Knoxville

Kira S. Birditt, University of Michigan

Edna Brown, University of Connecticut

Terri L. Orbuch, Oakland University

References

- Acitelli LK, Douvan E, & Veroff J (1993). Perceptions of conflict in the first year of marriage: How important are similarity and understanding? Journal of Personal and Social Relationships, 10(1), 5–19. doi: 10.1177/0265407593101001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acock AC, & Demo DH (1994). Family Diversity and Well-being. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Biesen JN, & Doss BD (2013). Couples’ agreement on presenting problems predicts engagement and outcomes in problem-focused couple therapy, 27(4), 658–663. doi: 10.1037/a0033422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Orbuch TL, & Bauermeister JA (2008). Religiosity and marital stability among Black American and White American couples. Family Relations, 57(2), 186–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00493.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Conger RD, & Meehan JM (2001). The influence of in-laws on change in marital success. Source: Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(3), 614–626. [Google Scholar]

- Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, & Katz LF (1992). How a couple views their past predicts their future: Predicting divorce from an oral history interview. Journal of Family Psychology, 5(3 & 4), 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Chong A, Gordon AE & Don BP (2017). Emotional support from parents and in-laws: The roles of gender and contact. Sex Roles, 76 369–379. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0587-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Gilligan M, VanderDrift L, & Pitzer L (2012). In-law relationships before and after marriage: Husbands, wives, and their mothers-in-law. Research in Human Development, 9(2), 106–125. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2012.680843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, VanderDrift LE, Dotterer AM, Birditt KS, & Zarit SH (2011). Support to aging parents and grown children in Black and White families. The Gerontologist, 51(4), 441–452. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Rauer AJ, Birditt KS, Brown E, Jager J, & Orbuch TL (2017). Social network typologies of Black and White married couples in midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(2), 571–589. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Rauer AJ, Birditt KS, Marini CM, Jager J, Brown E, & Orbuch TL (2018). “I love you, not your friends”: Links between partners’ early disapproval of friends and divorce across 16 years. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(9), 1230–1250. doi: 10.1177/0265407517707061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frierson GM, Pinto BM, Denman DC, Leon PA, & Jaffe AD (2019). Bridging the Gap: Racial concordance as a strategy to increase African American participation in breast cancer research. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(1), 1548–61. doi: 10.1177/1359150317740736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gager CT, & Sanchez L (2003). Two as one?: Couples’ perceptions of time spent together, marital quality, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 24(1), 21–50. doi: 10.1177/0192513X02238519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt R (2006). Couple similarity and marital satisfaction: Are similar spouses happier? Journal of Personality, 74(5), 1401–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga GC, Campos B, & Bradbury T (2007). Similarity, convergence, and relationship satisfaction in dating and married couples. Interpersonal Relations and Group Processes, 93(1), 34–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM (2014). What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann-Marriott BE (2006). Shared beliefs and the union stability of married and cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 1015–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00310.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, & George LJ (2001). The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(2), 237–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DP, Jackson GL, Green HD, Bradbury TN, & Karney BR (2015). The Analysis of duocentric social networks: A primer. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(1), 295–311. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach MS, & Braithwaite DO (1996). A binding tie: Supportive communication of family kinkeepers. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 24(3), 200–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Spitze G, & Logan JR (2003). Social support to parents-in-law: The interplay of gender and kin hierarchies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00396.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx J, Miller LQ, & Huffmon S (2011). Excluding mothers-in-law: A research note on the preference for matrilineal advice. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 1205–1222. doi: 10.1177/0192513X11402176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morr Serewicz MC, & Canary DJ (2008). Assessments of disclosure from the in-laws: Links among disclosure topics, family-privacy orientations, and relational quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 333–357. doi: 10.1177/0265407507087962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morr Serewicz MC, Hosmer R, Ballard RL, & Griffin RA (2008). Disclosure from in-laws and the quality of in-law and marital relationships. Communication Quarterly, 56, 427–444. doi: 10.1080/01463370802453642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, Bauermeister JA, Brown E, & McKinley BD (2013). Early family ties and marital stability over 16 years: The context of race and gender. Family Relations, 62(2), 255–268. doi: 10.1111/fare.12005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, & Veroff J (2002). A programmatic review: Building a two-way bridge between social psychology and the study of the Early Years of Marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(4), 549–568. doi: 10.1177/0265407502019004053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orbuch TL, Veroff J, Hassan H, & Horrocks J (2002). Who will divorce: A 14-year longitudinal study of black couples and white couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(2), 179–202. doi: 10.1177/0265407502192002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papp LM (2018). Topics of marital conflict in the everyday lives of empty nest couples and their implications for conflict resolution. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy, 17, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pasley K, Ihinger-Tallman M, & Coleman C (1984). Consensus styles among happy and unhappy remarried couples. Family Relations Special Issue: Remarriage and Stepparenting. 33(3), 451–457. doi: 10.2307/584716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick CA, Seidel AJ, Birditt KS, Zarit SH, & Fingerman KL (2017). Filial obligation and marital satisfaction in middle-aged couples. Gerontologist, 57(3), 417–428. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice CM (2008). The assimiliation of in-laws: The impact of newcomers on the communication routines of families. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 36, 74–97. doi: 10.1080/00909880701799311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenour CE (2012). Daughter-in-law standards for mother-in-law communication: Associations with daughter-in-law perceptions of relational satisfaction and shared family identity. Journal of Family Communication, 12, 93–110. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2010.537240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenour CE, & Kellas JK (2017). Making sense of hurtful mother-in-law messages : Applying attribution theory to the in-law triad. Communication Quarterly, 63(1), 62–80. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2014.965837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Slatcher RB, Trombello JM, & McGinn MM (2014). Marital quality and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 140–187. doi: 10.1037/a0031859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JD, & Levitt MJ (2007). Intergenerational relations with in‐laws in the context of the social convoy: Theoretical and practical implications. Journal of Social Issues, 63(4), 827–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00349.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serewicz MCM, Hosmer R, Ballard RL, & Griffin RA (2008). Disclosure from in-laws and the quality of in-law and marital relationships. Communication Quarterly, 56(4) 427–444. doi: 10.1080/01463370802453642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein JL (1990). The problem with in-laws. Journal of Family Therapy, 14, 390–412. doi: 10.1046/j..1992.00469.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, & Veroff J (2000). Family ties and the discontinuity of divorce in Black and White newlywed couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 349–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00349.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer SG, Veroff J, & Hatchett S (1996). Family ties and marital happiness: The different marital experiences of Black and White newlywed couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(3), 335–359. doi: 10.1177/0265407596133003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson HC, Hanna MA, Lavner JA, Bradbury TN, & Karney BR (2013). Discussion topic and observed behavior in couples’ problem-solving conversations: Do problem severity and topic choice matter? Journal of Family Psychology, 27(2), 330–335. doi: 10.1037/a0031534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH, & Wickrama KAS (2006). Ambivalence in mother-adult child relations: A dyadic analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(3), 235–252. doi: 10.1177/019027250606900302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AC, & Huston TL (2013). Shared reality and grounded feelings during courtship: Do they matter for marital success? Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(3), 681–696. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]