Abstract

Jasmonates (JAs) are plant hormones that regulate the biosynthesis of many secondary metabolites, such as hydroxycinnamic acid amides (HCAAs), through jasmonic acid (JA)-responsive transcription factors (TFs). HCAAs are renowned for their role in plant defense against pathogens. The multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporter DETOXIFICATION18 (DTX18) has been shown to mediate the extracellular accumulation of HCAAs p-coumaroylagmatine (CouAgm) at the plant surface for defense response. However, little is known about the regulatory mechanism of DTX18 gene expression by TFs. Yeast one-hybrid screening using the DTX18 promoter as bait isolated the key positive regulator redox-responsive TF 1 (RRTF1), which is a member of the AP2/ethylene-response factor family of proteins. RRTF1 is a JA-responsive factor that is required for the transcription of the DTX18 gene, and it thus promotes CouAgm secretion at the plant surface. As a result, overexpression of RRTF1 caused increased resistance against the fungus Botrytis cinerea, whereas rrtf1 mutant plants were more susceptible. Using yeast two-hybrid screening, we identified the BTB/POZ-MATH (BPM) protein BPM1 as an interacting partner of RRTF1. The BPM family of proteins acts as substrate adaptors of CUL3-based E3 ubiquitin ligases, and we found that only BPM1 and BPM3 were able to interact with RRTF1. In addition, we demonstrated that RRTF1 was subjected to degradation through the 26S proteasome pathway and that JA stabilized RRTF1. Knockout of BPM1 and BPM3 in bpm1/3 double mutants enhanced RRTF1 accumulation and DTX18 gene expression, thus increasing resistance to the fungus B. cinerea. Our results provide a better understanding of the fine-tuned regulation of JA-induced TFs in HCAA accumulation.

CUL3BPM E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate JA-responsive RRTF1 transcription factor stability and DTX18 gene expression in hydroxycinnamic acid amide secretion.

Introduction

Plants produce a diverse group of secondary metabolites. These compounds not only mediate interactions with biotic and abiotic environmental factors but also affect the qualitative traits of crop plants. Hydroxycinnamic acid amides (HCAAs), including p-coumaroylagmatine (CouAgm) and feruloylagmatine in Arabidopsis, are renowned for their role in plant defense against pathogens (Campos et al., 2014; Dobritzsch et al., 2016). Unlike minor classes of plant secondary metabolites, HCAAs have been found in a wide range of plant families (Campos et al., 2014). To date, the pathway of HCAA biosynthesis and secretion has been clearly identified and characterized in Arabidopsis (Muroi et al., 2009; Dobritzsch et al., 2016). At5g61160 encodes a p-coumaroyl-CoA: agmatine N4-p-coumaroyl transferase (ACT) catalyzing the last key step in the biosynthesis of CouAgm and feruloylagmatine, and At3g23550 encodes a multidrug and toxin extrusion (MATE) transporter DETOXIFICATION18 (DTX18), secreting CouAgm for extracellular accumulation at the plant surface. Both genes are required for the plant defense response (Muroi et al., 2009; Dobritzsch et al., 2016). To survive pathogen infection, plants produce one or more signaling molecules, including jasmonic acid (JA), allowing the rapid transcription of genes coding for enzymes or transporters involved in the accumulation of protective secondary metabolites, such as HCAAs (Muroi et al., 2009; Pieterse et al., 2012; Dobritzsch et al., 2016). Therefore, studying the regulatory mechanisms of gene expression by JA-responsive transcription factors (TFs) is of major importance in the understanding of HCAA accumulation.

In general, it can be stated that plant responses to wounding and insect herbivory are mediated by JAs, and attack by necrotrophic pathogens triggers JA/ethylene (ET)-dependent responses (Howe et al., 2018). CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1 (COI1) encodes an F-box protein as the receptor that is specific to the JA signal transduction pathway. COI1 is part of an E3 ubiquitin (UBQ) ligase complex of the Skp1/Cullin/F-box (SCFCOI1) type that can target specific substrates for degradation by the 26S proteasome. The Jasmonate ZINC-FINGER PROTEIN EXPRESSED IN INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM-motif (JAZ) proteins have been identified as the targets of COI1 (Chini et al., 2016; Wasternack and Feussner, 2018). E3 UBQ ligases are involved in the regulation of TFs stability in JA signaling, and continuous activation of TF activity is potentially lethal (Jung et al., 2015; Chico et al., 2020). The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-type TFs MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 are central nodes in the JA pathway to fine-tune plant defense responses to pathogen infection, wounding, insect attacks, and plant growth (Fernández-Calvo et al., 2011; Schweizer et al., 2013; Qi et al., 2015; Zander et al., 2020). Several E3 UBQ ligase-related components have been identified to regulate MYCs stability. For instance, the E3 UBQ ligase PUB10 mediates the degradation of MYC2 (Jung et al., 2015). The BTB/POZ-MATH (BPM) proteins are adaptors of Cullin3-based E3 UBQ ligases (CUL3BPM E3), which target MYCs for degradation (Chico et al., 2020). To optimize plant fitness, TF stability needs to be tightly regulated. Therefore, more E3 UBQ ligase regulators should be functionally identified in the future.

The key TFs usually regulate the transcription of multiple biosynthesis or transporter genes in a pathway (Zhou and Memelink, 2016). Interestingly, ACT is highly coexpressed with DTX18 in different plant tissues (Dobritzsch et al., 2016), and the expression of both genes was rapidly induced by pathogen infection (Muroi et al., 2009; Dobritzsch et al., 2016), suggesting that one core TF could exist to regulate the expression of both genes. In 2018, our group identified this core positive regulator, OCTADECANOID RESPONSIVE ARABIDOPSIS AP2/ERF (ORA) 59 (ORA59), which is involved in JA/ET-induced HCAA biosynthesis (Li et al., 2018). ORA59 could form homodimers and interact with MEDIATOR 25 (MED25) to activate both ACT and DTX18 gene expression (Li et al., 2018). In addition, ORA59 directly binds to the two GCC-boxes in the ACT gene promoter but does not bind to the promoter of the DTX18 gene due to missing GCC boxes (Li et al., 2018). These results suggest that other ORA59-regulated TFs probably exist to directly activate the transcription of the DTX18 gene.

Therefore, to explore the molecular mechanism of HCAA secretion, it is necessary to identify the putative TF and its regulation mechanism for DTX18 gene expression. Promoter sequence analysis suggests the involvement of more than one type of TF in DTX18 gene regulation. This study was designed to search for such TFs. Using the fragments of the DTX18 promoter in yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) screening, the JA-responsive TF redox-responsive TF 1 (RRTF1, AP2/ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 109) was found to interact with the promoter. It has been widely reported that RRTF1 plays important roles in the response to salt stresses (Bahieldin et al., 2016, 2018), fungus (Matsuo et al., 2015), and herbivores (Schweizer et al., 2013). Here, we demonstrated that RRTF1 positively regulates DTX18 gene expression and CouAgm secretion and thus mediates the plant defense response to Botrytis cinerea. Furthermore, it was shown that RRTF1 interacts directly with BPM proteins. This specific RRTF1–BPM interaction is regulated under the JA signaling pathway and plays an integral part in the transcriptional regulation of the DTX18 gene and CouAgm secretion.

Results

RRTF1 directly binds to the DTX18 promoter

To identify TFs binding to the DTX18 promoter, Y1H system was performed. Various DTX18 promoter fragments (Supplemental Figure S1) were used to screen a JA-treated Arabidopsis cDNA library (Li et al., 2018). DTX18 promoter fragment I (−1 bp to −328 bp), fragment II (−329 bp to −705 bp), and fragment III (−706 bp to −1097 bp) fused to the HIS3 selection marker were used as bait to isolate DNA-binding proteins from a cDNA library cloned in fusion with the GAL4 activation domain in the yeast expression vector pACTII. In total, 22 cDNA clones were isolated from the fragment II derivative of yeast colonies that showed growth on medium lacking histidine, while nothing was identified from fragments I and III (Supplemental Table 1). A total of 2.6 million fragment II derivatives of yeast transformants were screened for reporter gene activation results with a probability of ≥99% of screening every mRNA species, representing near-complete screenings of the cDNA library. Based on their sequence blast, 22 clones were subdivided into 3 classes: 3 clones (pACT/II-1-JA) encoded L-ascorbate peroxidase (At1g07890), 5 clones (pACT/II-2-JA) encoded pectinesterase (At1g02813), and 14 clones (pACT/II-3-JA) encoded RRTF1 (At4g34410). L-Ascorbate peroxidase and pectinesterase are not involved in direct DNA-binding; thus, RRTF1 was selected for further analysis (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the fragment II promoter sequence analysis in the Plant Promoter Analysis Navigator (PlantPAN; http://PlantPAN2.itps. ncku.edu.tw) identified the TFmatrixID_0081 (−556 to −565, GAGCCGGCAG), which is recognized by RRTF1 (Chow et al., 2016). To confirm the direct interaction between RRTF1 and the DTX18 promoter, an in vitro electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) and an in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation quantitative polymerase chain reaction (ChIP-qPCR) assay were performed. As shown in Figure 1B, RRTF1 was able to bind to DTX18 promoter fragment II. The band shift of RRTF1 in the gel was completely abolished when the binding site GAGCCGGCAG at positions −556 to −565 was mutated to GATTTTTTAG. In addition, binding of RRTF1 was completely abolished when 100-fold excess of unlabeled DTX18 fragment II was added. This suggests that the corresponding sequence GAGCCGGCAG is essential for binding to RRTF1. Furthermore, a ChIP-qPCR assay showed that the RRTF1–HA fusion protein binds to the DTX18 promoter (Figure 1C). As expected, RRTF1 did not bind to the reference gene UBQ10 promoter (Figure 1C), and ORA59 did not bind to the DTX18 promoter (Figure 1D). These results indicated that RRTF1, not ORA59, directly binds to the promoter of the DTX18 gene.

Figure 1.

RRTF1 binds to the DTX18 promoter. (A) Y1H analysis of RRTF1 binding to the DTX18 promoter fragment II. Yeast cells were grown on synthetic dropout medium lacking leucine and histidine (SD/-LH) supplemented with 10-mM 3-AT. Growth was monitored after 7 d. (B) EMSA of a WT (Biotin-F) or mutated (Biotin-mF). DTX18 promoter fragment II with His-RRTF1 purified from E. coli BL21 (DE3). Plus or minus signs indicate binding mixtures with or without 0.5-μg recombinant His fusion protein, 2-nM biotin-labeled WT DTX18 promoter (Biotin-F) and mutant DTX18 promoter (Biotin-mF), respectively. In addition, a 10- or 100-fold excess of unlabeled DTX18 fragment II F or mF was added as competitor to the EMSA incubation mixtures. The arrow indicates the protein probe complex. (C, D) ChIP assays show RRTF1 (C) and ORA59 (D) bind to the promoter of DTX18. ChIP assays were conducted by real-time PCR after normalizing with the input DNA. The reference gene UBQ10 promoter and the fragment of DTX18 coding sequence were used as a negative control. The asterisks **P < 0.01 and ns represent significant and nonsignificant difference by a pairwise analysis, respectively. CDS represents the coding sequence.

RRTF1 activates DTX18 gene expression in Arabidopsis protoplasts

Our previous results showed that ORA59 could activate the transcript of the DTX18 gene (Li et al., 2018). To confirm whether RRTF is the direct regulator of DTX18 gene expression, Arabidopsis rrtf1 mutant protoplasts transactivation assays were performed. Protoplasts were cotransformed with the reporter plasmid consisting of the DTX18 promoter (−1 to −1097) fused to GUS (DTX18FLpro-GUS) and GFP (DTX18FLpro-GFP) and the effector plasmids carrying the RRTF1 or ORA59 gene under the CaMV35S promoter. RRTF1 was found to activate the DTX18FLpro-GUS reporter gene by approximately six-fold, whereas the effector ORA59 (Li et al., 2018) had no effect on the rrtf1 mutant background (Figure 2A). In addition, ORA59 did not act synergistically with RRTF1 to activate the DTX18FLpro-GUS reporter gene. To further confirm the transactivation of the DTX18 promoter by RRTF1 in planta, GFP expression was analyzed. Strong GFP signals were observed upon coexpression of DTX18FLpro-GFP with RRTF1 (Figure 2B) compared to the control (DTX18FLpro-GFP and ORA59). Furthermore, immunoblot analysis with anti-GFP antibodies of the total cellular protein revealed that RRTF1 drastically increased the amount of GFP protein compared to ORA59 (Figure 2C). To study whether RRTF1 acts via the binding site GAGCCGGCAG at positions −556 to −565, we mutated the binding site to GATTTTTTAG, generating the mDTX18FLpro-GUS derivative. This mutation abolished the GUS activity conferred by RRTF1 (Figure 2D), indicating that GAGCCGGCAG is the binding site of RRTF1, as previously reported (Chow et al., 2016). Taken together, our experiments show that RRTF1, not ORA59, activates the DTX18 promoter.

Figure 2.

RRTF1 activates DTX18 gene expression in Arabidopsis rrtf1 mutant protoplasts. (A, D) RRTF1 trans-activate the DTX18 promoter (A) and its mutated promoter (D) fused GUS. Arabidopsis rrtf1 mutant protoplasts were co-transfected with plasmids carrying 2-μg DTX18FLpro-GUS and 2-μg overexpression vectors containing 35S::RRTF1 or 35S::ORA59, as indicated. Values represent means ± standard error (se) of triplicate experiments and are expressed relative to the control. (B) RRTF1 trans-activate the DTX18 promoter fused GFP. GFP fluorescence images of Arabidopsis rrtf1 mutant protoplasts co-transformed with 2-μg constructs DTX18FLpro-GFP alone and with 2-μg overexpression vectors containing 35S::ORA59 or 35S::RRTF1. Bar = 10 μm. (C) Transiently expressed DTX18FLpro-GFP protein which is activated by RRTF1. The 10-μg total proteins were extracted and detected with anti-GFP antibodies. Double asterisks represent significant values.

RRTF1 positively regulates B. cinerea-induced accumulation of CouAgm at the plant surface

To further investigate the role of RRTF1 and ORA59 in B. cinerea-induced CouAgm secretion at the plant surface, a series of rrtf1, ora59, and rrtf1/ora59 mutants and overexpression lines of the 35S::RRTF1, 35S::ORA59, and 35S::RRTF1;35S::ORA59 genes in the same genetic background (Col-0) were analyzed (Bahieldin et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). Compared with the wild-type (WT) plants, all mutant lines and 35S::RRTF1 overexpression lines showed no visible phenotype (Supplemental Figure S2), while 35S::ORA59 and 35S::RRTF1;35S::ORA59 overexpression lines showed a severe dwarf phenotype (Pré et al., 2008; Bahieldin et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). All lines were inoculated with a B. cinerea spore suspension, and the disease progression and number of B. cinerea spores were determined. As expected, inoculation with B. cinerea highly induced the expression of several defense-related genes, including the plant defensin PDF1.2 and the TF ORA59 (Supplemental Figure S3), indicating that the plant defense response was successfully induced by B. cinerea infection. Leaf lesions were scored in three different classes (I–III) according to disease severity, as shown in representative leaves in Figure 3A. In the WT, approximately 50% of infected leaves were distributed among the less severe class I after 3 d of infection (Figure 3B;Supplemental Table 2). As expected, 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants showed strongly enhanced resistance to B. cinerea, with 76% of leaves in class I, whereas infected leaves from ora59 and ora59/rrtf1 mutant plants were mainly distributed among the more severe classes II and III (Figure 3B;Supplemental Table 2). Interestingly, infected rrtf1 mutant leaves were relatively tolerant of B. cinerea compared with ora59 and ora59/rrtf1 mutant plants (Figure 3B). The differences in class distribution were statistically significant, and the results were consistently reproduced in three independent infection assays. For B. cinerea, successful penetration of the cell wall requires enzymes capable of degrading pectin, such as the endopolygalacturonase Bcpg1 (Sun et al., 2017). To assess whether the expression of Bcpg1 genes was affected in different genotypes of plants during infection, the transcript levels of Bcpg1 were investigated by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) from 0.5- to 72-h post-inoculation (hpi). Compared with the WT plants, the lowest and highest transcript levels of Bcpg1 were observed in 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants and ora59/rrtf1 mutant plants, respectively (Supplemental Figure S4). These results are in agreement with Figure 3B, indicating that the growth of B. cinerea is significantly reduced in 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants, comparable to 35S::ORA59 plants. Taken together, these results demonstrate that RRTF1 plays a positive role in resistance to B. cinerea.

Figure 3.

RRTF1 acts downstream of ORA59 to regulate CouAgm secretion. (A) Representative disease symptoms at 3 d after inoculation. Class I, no visible disease symptoms or nonspreading lesion; II, spreading lesion with or without surrounded by a chlorotic halo; and III, spreading lesion with extensive tissue maceration. (B) Distribution of disease severity classes. Disease severity is expressed as the percentage of leaves falling in disease severity classes. Data represent 200 leaves of 50 plants per genotype. O59, 35S::ORA59 plants; RTF, 35S::RRTF1 plants; O-R, 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants; o59, ora59 mutants; rtf, rrtf1 mutants; o/r, ora59/rrtf1 mutants. The differences between genotypes were analyzed relative to the WT genotype with Pearson’s Chi-squared test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). (C) CouAgm levels were determined in leaves of the inoculum of different genotypes by LC–MS. Values represent means ± standard deviation (sd) of triplicate experiments. Each tested genotype is the mixture of three independent lines. **P < 0.01 represents significant difference. (D) CouAgm levels were determined in droplets of the inoculum of different genotypes by LC–MS (Replicate 1). Triple experiments are conducted for each genotype, and each treatment is the mixture of six independent plants. Box plots show median, maximum and minimum. **P < 0.01 represents significant difference. (E, F) Transcript analysis of ACT (E) and DTX18 (F) in four mature leaves of different genotype plants infected with B. cinerea spores or water as indicated by qRT-PCR. UBQ10 was used as an internal control. Values represent means ± standard deviation (sd) of four mature leaves of three biological replicates and are expressed relative to the control. Each tested genotype is the mixture of three independent lines. **P < 0.01 represents significant difference.

To determine the extent of CouAgm in B. cinerea-infected plants, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis was performed. The CouAgm content in leaves was higher than in the whole plant in different genotypes (Figure 3C;Supplemental Figure S5); therefore, the leaf was selected for further analysis. In contrast to WT and empty vector (EV) plants, 35S::ORA59 and 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants showed enhanced levels of CouAgm in the leaves of B. cinerea inoculation sites (Figure 3C), suggesting that ORA59 is required and sufficient for CouAgm biosynthesis. However, rrtf1 mutant plant leaves contained similar levels of CouAgm as WT, EV, and 35S::RRTF1 plant leaves, indicating that rrtf1 plants still retain the ability to biosynthesize CouAgm. Interestingly, extracellular CouAgm accumulation on 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 and 35S::RRTF1 plant leaf surfaces was higher than on 35S:ORA59 plants during B. cinerea infection (Figure 3D;Supplemental Figure S6). In addition, extracellular CouAgm accumulation on 35S::ORA59 plant leaf surfaces with B. cinerea infection was higher than those undergoing water treatment (Figure 3D;Supplemental Figure S6), indicating that DTX18 gene expression is induced by B. cinerea infection. As expected, extracellular CouAgm accumulation on all mutant plant leaf surfaces with B. cinerea infection was significantly reduced compared with WT and EV plants. In addition, CouAgm accumulated highly in leaves 48 h after JA treatment in WT (Li et al., 2018) and rrtf1 plants (Supplemental Figure S7A). However, extracellular CouAgm accumulation on rrtf1 plant leaf surfaces was barely affected after JA treatment (Supplemental Figure S7B). These observations suggest that RRTF1 is required for the export of CouAgm. Subsequently, the expression patterns of ACT and DTX18 were analyzed in all lines with and without B. cinerea infection. As expected, expression of ACT and DTX18 was induced by B. cinerea infection (Figure 3, E and F). As shown in Figure 3E, the expression levels of ACT were strongly induced in 35S::ORA59 and 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants compared with the control lines with and without B. cinerea infection. In the ora59 and ora59/rrtf1 mutant plants, the expression levels of ACT were dramatically reduced compared with the control lines, confirming previous findings showing that ACT is directly activated by ORA59 (Li et al., 2018). In addition, the expression levels of ACT were induced to similar levels in response to B. cinerea infection in 35S::RRTF1, rrtf1, and control plants, suggesting that ACT was not a target gene of RRTF1. As shown in Figure 3F, the expression of DTX18 was higher in the 35S::RRTF1 and 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants compared to WT and ora59 mutant plants with and without B. cinerea infection. In contrast, the expression of DTX18 was significantly reduced in the rrtf1 and rrtf1/ora59 mutant plants compared with the WT plants with water treatment and B. cinerea infection. This was consistent with Figure 2A, which shows that ORA59 could not activate DTX18 gene expression in rrtf1 mutant protoplasts, indicating that RRTF1 is required for the transcription of the DTX18 gene and export of CouAgm. As expected, the RRTF1 transcript was significantly decreased in ora59 mutant lines and increased in ORA59 overexpressing lines, respectively (Supplemental Figure S8). This result demonstrated that RRTF1, as an ORA59 putative regulatory factor, directly activates the DTX18 gene in HCAA secretion.

RRTF1 interacts with BPM family proteins

To further identify the regulator of RRTF1, Y2H screenings of 14-d-old Arabidopsis seedling cDNA libraries were performed (Li et al., 2018). This resulted in the isolation of nine positive colonies capable of growing on minimal medium. From these candidate RRTF1 interactors, only one cDNA sequence (9# clone) was in frame with the GAL4 AD. This plasmid contained a partial cDNA encoding the protein BPM1 (At5g19000), lacking the last 263 amino acids in the C-terminal region (Figure 4A), indicating that this region is not necessary for interaction with the RRTF1 protein. BPM1 consists of 442 amino acids and contains a BTB domain (203–347 AA) in the middle of the protein and a MATH domain (38–150 AA) in the N-terminal region. It has been reported that BPM1 belongs to the BTB/POZ family, composed of six members, BPM1–BPM6 (Weber et al., 2005). This suggested that RRTF1 could interact with other BPM proteins. As shown in Supplemental Figure S9, we could indeed confirm the RRTF1–BPM3 interaction by Y2H assays, and RRTF1 cannot interact with BPM2, BPM4, BPM5, and BPM6. Furthermore, the partial BPM1 (1–179 AA) in the Y2H screens illustrated that the BTB domain is not required for interaction with RRTF1. To further confirm the binding domain, a new truncated BPM1 version of 120 amino acids (35–154 AA, BPM1–MATH) composed of the MATH domain was developed. BPM1–MATH is capable of binding to RRTF1, revealing that the MATH domain is responsible for the BPM1–RRTF1 interaction. Likewise, we sought to determine which RRTF1 region mediates the interaction with BPM1 proteins. The results showed that the N-terminal region of RRTF1 was responsible for the interactions with BPM1 (Supplemental Figure S10).

Figure 4.

RRTF1 interacts with BPM1 in vitro and in vivo. (A) RRTF1 interacts with BPM1 lacking the last 263 amino acids in Y2H screening. Schematic representation of BPM1 protein. Yeast cells expressing RRTF1 proteins fused to the GAL4 BD and BPM1 fused to the GAL4 AD were spotted on SD medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD/-LW) to select for the plasmids and on SD/-LWH with 15-mM 3-AT to select for transcriptional activation of the His3 gene. Yeast cells transformed with the empty plasmids pAS2.1 and pACT2 were used as controls. Growth was monitored after 5 d. (B) BiFC assays of the interaction between RRTF1 and BPM1 or BPM1–MATH domain. YFP fluorescence images alone or merged with RFP nuclear marker and bright-field images of Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts co-transfected with constructs encoding the indicated fusion proteins with YFP at the C terminus or the N terminus and RFP nuclear marker. Bar=20 μm. (C) In vitro interaction between HA–BPM1 and Strep-RRTF1. HA–BPM1, HA–BPM2, or HA–BPM1–MATH protein was incubated with immobilized Strep-RRTF1 for 2 h. The immuno-precipitated fractions and input were detected with anti-HA antibody and anti-Strep antibody, respectively. Asterisks denote significant bands from HA antibody. (D) CoIP of RRTF1–HA from Arabidopsis thaliana with His–BPM1. Total protein was extracted from 14-d-old seedlings of one representative 35S::RRTF1–HA transgenic line. The protein was allowed to bind to recombinant His-BPM1 immobilized on His-binding resin for 2 h. His protein was used as a control to show the binding specificity of the HA-tagged proteins toward BPM1. Input, the amount of the different proteins at the start of the experiment; pull-down, the amount of proteins detected at the end of the experiment after the washing steps.

The RRTF1 and BPM1 interactions were tested in planta using the BiFC assay. Strong YFP signals were observed upon coexpression of BPM1–cYFP with nYFP–RRTF1 and BPM1–MATH–cYFP with nYFP–RRTF1 (Figure 4B) compared to negative controls (BPM1–cYFP or BPM1–MATH–cYFP coexpressed with nYFP or cYFP coexpressed with nYFP–RRTF1). To verify the interaction in vitro, a pull-down assay was performed, and the results showed that Strep-RRTF1 could interact with HA–BPM1 and HA–BPM1–MATH and could not interact with BPM2 (Figure 4C), which is consistent with our Y2H results. To further investigate the interaction between BPM1 and RRTF1, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) experiment using recombinant His-BPM1 and HA-tagged RRTF1 from 35S::RRTF1–HA stable transgenic plants. As shown in Figure 4D, HA–RRTF1 was pulled-down by Ni-NTA agarose beads with His-BPM1 but was not pulled-down by Ni-NTA agarose beads with His alone, indicating that RRTF1 is able to directly bind to BPM1. These results indicated that the RRTF1 protein interacts with the BPM1 protein in vitro and in vivo.

RRTF1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome under JA signaling

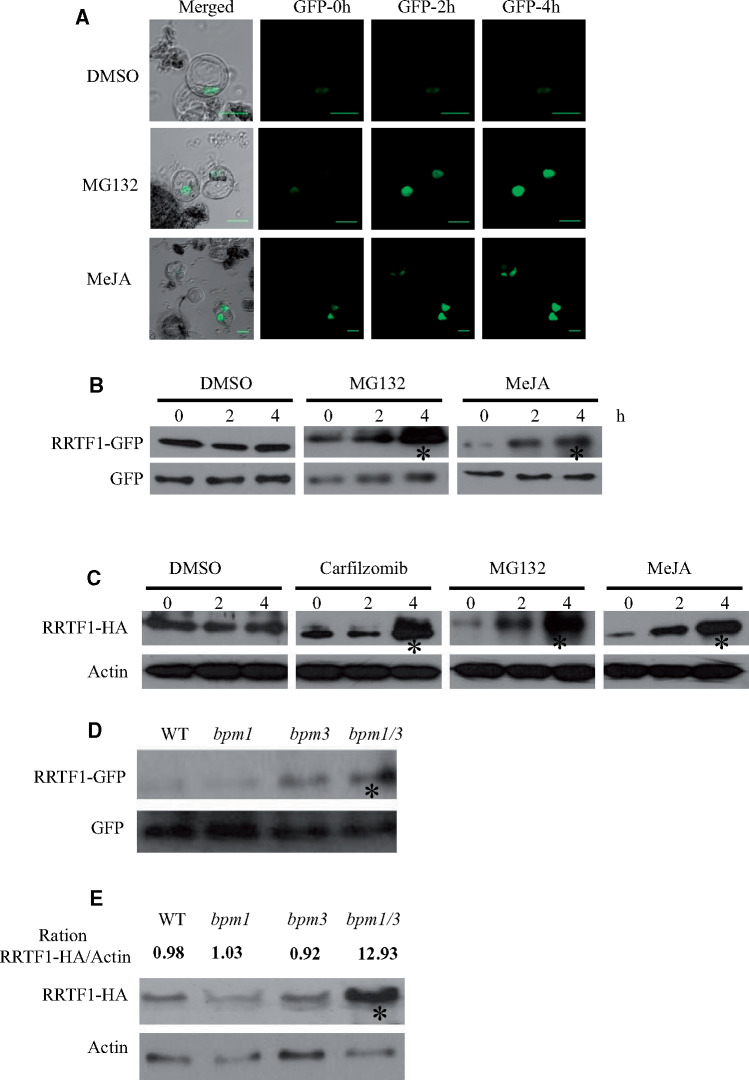

Our previous results showed that the transcription of the ORA59 gene is induced by JA and a JA/ET combination (Li et al., 2018). To test whether RRTF1 expression was similar to ORA59 expression, we analyzed the expression of the RRTF1 gene in WT plants and different mutants. In agreement with previous findings (Li et al., 2018), the positive marker gene PDF1.2 is induced by JA or ET and is superinduced by a combination of both (Supplemental Figure S11A). As expected, PDF1.2 gene expression was strongly reduced in both coi1-1 and ein2-1 mutants compared with the WT. However, RRTF1 gene expression was induced by JA and weakly induced by JA/ET, and it was strongly reduced in coi1-1 but not in ein2-1 mutants compared with the WT (Supplemental Figure S11B). These results indicate that the RRTF1 gene is responsive to JA, consistent with previous results that the RRTF1 gene is significantly reduced in the myc2/3/4 triple mutant (Schweizer et al., 2013). Previously, it was shown that BPM proteins could interact with CUL3 proteins, which act as scaffolding subunits of multimeric E3-ligases that can target their substrates for degradation via the 26S proteasome (Weber et al., 2005). More recently, it was shown that BPM proteins target JA-regulated MYCs for CUL3BPM E3-mediated degradation (Chico et al., 2020). Since RRTF1 interacts with BPM1 and is responsive to the JA gene expression level, we then investigated if its stability in protoplasts was associated with the 26S proteasome in a JA-dependent manner. A GFP-tagged RRTF1 protein or just GFP was expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts. JA and MG132 treatment result in the increased accumulation of GFP with time, whereas dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) had no effect (Figure 5A). JA or MG132 treatment drastically increased the quantity of RRTF1–GFP protein, while GFP alone as a negative control had no affect (Figure 5B). To confirm these results, we analyzed the RRTF1–HA levels in 35S::RRTF1–HA stable transgenic plants. Similar to Figure 5B, RRTF1–HA showed an enhanced stability after MG132, Carfilzomib, and MeJA treatment, while actin levels as an internal control were not affected (Figure 5C). The results of stable transgenic plants were similar to those of transient protoplasts, confirming that RRTF1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome and stabilized by MeJA. In addition, accumulated RRTF1–GFP protein was observed in the leaf protoplasts of the bpm1bpm3 double mutant but not in the WT (Figure 5D). To confirm these results, we next introgressed RRTF1–HA from an independent 35S::RRTF1–HA line into a bpm1, bpm3, and bpm1bpm3 line and thus analyzed the effect of BPM knockout on RRTF1 protein levels. As shown in Figure 5E, RRTF1 accumulated more in the bpm1bpm3 double mutant than in the bpm1 or bpm3 single mutant and WT plants. Taken together, these results indicated that RRTF1 protein is subjected to degradation through the 26S proteasome pathway after binding with BPM proteins and that JA stabilizes RRTF1 protein.

Figure 5.

RRTF1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome and stabilized under JA treatment. (A) Confocal laser scanning microscopy images of Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts expressing RRTF1–GFP or GFP. Eighteen hours after transformation, protoplasts were treated for different time points with 50-μM MeJA and/or 50-μM MG132 or 0.1% DMSO. Bar = 20 μm. (B) Steady-state protein amounts of RRTF1–GFP and GFP in Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts. Proteins were detected with anti-GFP antibodies. Asterisks denote significant bands from GFP antibody. (C) Immunoblot analysis of RRTF1–HA and Actin protein levels in 14-d-old 35S::RRTF1–HA transgenic plants were treated for different time points with 50-μM MeJA and/or 50-μM MG132 or 2.5-μM Carfilzomib or 0.1% DMSO. The proteins were isolated and tested with anti-HA and Actin antibodies, respectively. Asterisks denote significant bands from HA antibody. (D) Transiently expressed RRTF1–GFP and GFP proteins in WT, bpm1, bpm3, bpm1bpm3 Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts. The proteins were extracted 18 h after the transformation of protoplasts and detected with anti-GFP antibodies. Asterisks denote significant bands from GFP antibody. (E) Immunoblot analysis of RRTF1–HA and Actin protein levels in 14-d-old WT, bpm1, bpm3, bpm1bpm3 background plants which overexpressed 35S::RRTF1–HA plasmid. The proteins were isolated and tested with anti-HA and Actin antibodies, respectively. Asterisks denote significant bands from HA antibody. The ration of RRTF1–HA/Actin content was quantified by Graphpad.

BPMs repress the activity of RRTF1

To further elucidate the significance of BPM proteins and the RRTF1 interaction, Arabidopsis protoplast transactivation assays were performed. The cotransformation of the DTX18FLpro-GUS reporter and 35S::RRTF1 effector resulted in strong activation of approximately six-fold (Figure 2A). The addition of the 35S::BPM1 or 35S::BPM3 effector plasmid resulted in the repression of RRTF1 activity (Figure 6A). These results support the previous protein–protein interaction assays, where RRTF1 was found to interact with BPM1 and BPM3.

Figure 6.

BPMs repress the activity of RRTF1. (A) Trans-activation assays of DTX18 promoter by RRTF1, BPM1, or BPM3. Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts were co-transformed with 2-μg DTX18FLpro-GUS and 1-μg overexpression vectors 35S::RRTF1, 35S::BPM1 or 35S::BPM3, as indicated. (B) Distribution of disease severity classes. Disease severity is expressed as the percentage of leaves falling in disease severity classes. Data represent 200 leaves of 50 plants per genotype, WT, bpm1, bpm3, and bpm1/3 double mutants. The differences between genotypes were analyzed relative to the WT genotype with Pearson’s Chi-squared test (*P < 0.05). (C) CouAgm levels were determined in droplets of the inoculum of different genotype plants infected with B. cinerea spores or water as indicated by LC–MS. Values represent means ± standard deviation (sd) of triplicate experiments. Each tested genotype is the mixture of three independent lines. (D) Transcript analysis of DTX18 in four mature leaves of different genotype plants infected with B. cinerea spores or water as indicated by qRT–PCR. UBQ10 was used as an internal control. Values represent means ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate experiments and are expressed relative to the control. Each tested genotype is the mixture of three independent lines. **P < 0.01 and ns represent significant and nonsignificant values, respectively.

To identify the role of BPM proteins in CouAgm secretion, a series of bpm1, bpm3, and bpm1/3 mutant plants infected by B. cinerea were analyzed. Interestingly, bpm1/3 plants showed enhanced resistance to B. cinerea, with 60% of the leaves in class I, and both bpm1 and bpm3 single mutant lines showed similar percentages of lesion distribution in class I as WT plants (Supplemental Table 3). As shown in Figure 6B, pathogen infection assays showed that both bpm1 and bpm3 single mutants were more sensitive to Botrytis than bpm1/3 double mutant lines. As expected, lower transcript levels of Bcpg1 were observed in bpm1/3 double mutant plants compared with WT, bpm1 and bpm3 plants, especially from 24 to 72 hpi (Supplemental Figure S12), which supports that the growth of B. cinerea is significantly reduced in bpm1/3 double mutant plants compared with the WT, bpm1 and bpm3 plants. Moreover, the leaf surface CouAgm levels (Figure 6C) and the transcript levels of the DTX18 gene (Figure 6D) in the double bpm1/3 mutants were substantially higher than levels in the bpm1 and bpm3 single mutants, suggesting that the RRTF1 protein accumulated in double bpm1/3 mutants, which is consistent with our previous results (Figure 5C). Taken together, BPM proteins are necessary for the degradation of RRTF1 and the repression of RRTF1 activity on DTX18 gene expression in the plant defense response.

Discussion

JAs, as key signaling molecules, regulate the biosynthesis of various secondary metabolites, including HCAAs (Zhou and Memelink, 2016). HCAAs, a kind of phytoalexins in plant leaves, are transported onto the leaf surface for extracellular accumulation to prevent colonization by pathogens (Dobritzsch et al., 2016). The MATE transporter DTX18 has been recently reported to secrete CouAgm out of the cell (Dobritzsch et al., 2016). JA accumulation activates TFs, which could directly bind to cis-acting elements and regulate the expression of target genes. Until now, only one JA/ET-induced TF, ORA59, involved in the regulation of HCAA biosynthesis has been characterized (Li et al., 2018). ORA59 belongs to the APETALA2/ethylene-response factors (AP2/ERF) family, and its protein accumulation is strongly reduced by salicylic acid (SA; Pré et al., 2008; Van der Does et al., 2013). Here, we identified a new AP2/ERF factor RRTF1 as an important regulator of HCAA secretion. It has been reported that both RRTF1 and DTX18 are strongly induced upon JA signaling (Cai et al., 2014; Matsuo et al., 2015; Dobritzsch et al., 2016). In this study, using the DTX18 promoter as bait in a Y1H screening, RRTF1 interacted with the DTX18 promoter. The expression levels of the DTX18 gene were higher in the RRTF1-overexpressing lines and lower in the rrtf1 mutant seedlings compared to the WT, indicating the important roles of RRTF1 in the regulation of DTX18 gene expression. In the ORA59-overexpressing microarray data, both ACT and DTX18 transcripts were significantly increased (Pré et al., 2008). Our previous report demonstrated that ORA59 is necessary for expression of the ACT gene as well as the DTX18 gene (Li et al., 2018). However, we did not find that ORA59 could directly bind the DTX18 gene promoter (Li et al., 2018), indicating that other ORA59-regulated TFs probably directly activate DTX18 gene expression.

Interactions between the cis-acting DNA elements and the trans-acting TFs determine the gene expression. It has been well established that the JA-responsive activity of promoters containing the G-box (CACGTG, Benedetti et al., 1995) or the GCC motif (GCCGCC, Lorenzo et al., 2003) is dependent on COI1. The G-box and G-box-like sequence are commonly present in promoters that respond to JA, and the GCC motif is commonly found in promoters that respond in a synergistic manner to JAs combined with ET (Zarei et al., 2011). Our previous report showed that the JA/ET-responsive ACT gene contains two GCC motifs in its promoter, and a single GCC-box is not sufficient to be activated in response to JA/ET (Li et al., 2018). As shown in Supplemental Figure S1, we also found that two G-boxes are present at positions −245 to −250 and −531 to −536 of the RRTF1 gene promoter, respectively, supporting our results showing that RRTF1 gene expression is responsive to JA but not JA/ET. Our finding is consistent with the previous report that RRTF1 gene expression is significantly reduced in the myc2/3/4 triple mutant compared with the WT (Schweizer et al., 2013). Recently, RRTF1 was identified as a direct MYC2 and MYC3 target by ChIP-seq (Van Moerkercke et al., 2019; Zander et al., 2020), confirming that RRTF1 is regulated by JA. In addition, we showed that RRTF1 binds the GAGCCGGCAG element at positions −556 to −565. This element includes a GCCGGC sequence that is very similar to the GCC motif recognized by ORA59 (Pré et al., 2008; Li et al., 2018). In addition, RRTF1 is not directly regulated by ORA59 in ChIP-seq data (Zander et al., 2020). RRTF1 encodes a member of the B-3 group of the AP2/ERF family, and it has low homology, including its AP2 DNA binding domain, with other group members, suggesting that RRTF1 may have a unique role(s) without genetic redundancy to other ERF family members.

Several JA-responsive AP2/ERF TFs are known to regulate plant secondary metabolite biosynthesis and mediate against environmental stresses (Zhou and Memelink, 2016). It has been reported that RRTF1 is a JA-responsive factor and mediates the cross-talk between JA and auxin (Cai et al., 2014; Ye et al. 2020). RRTF1 also regulates a set of tryptophan biosynthetic enzyme genes and promotes tryptophan metabolism, thus improving plant salt stress tolerance (Bahieldin et al., 2016, 2018). In addition, RRTF1 has been shown to play a positive role in resistance to Spodoptera littoralis herbivory (Schweizer et al., 2013), indicating that RRTF1 is involved in the plant defense response. In this study, we found that RRTF1 is directly involved in plant surface HCAA accumulation and thus protects plants against the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. Plants with disrupted RRTF1 expression were found to be less resistant to the development of early disease symptoms of B. cinerea infection, whereas RRTF1-overexpressing lines were more resistant. However, the results do not agree with a previous publication where the authors concluded that plants overexpressing RRTF1 are susceptible to the necrotrophic pathogen Alternaria brassicae (Matsuo et al., 2015). It is surprising that a dwarf phenotype and flower of RRTF1-overexpressing lines was observed by Matsuo et al. (2015). However, we did not observe phenotypic differences between RRTF1-overexpressing lines and WT, which is consistent with previous reports (Bahieldin et al., 2016, 2018). Therefore, it is possible that the different observations are caused by phenotypic differences.

JAs control RRTF1 not only at the transcriptional level but also the de novo synthesis of protein. Our western blot results showed that MeJA promotes RRTF1 protein accumulation. In addition, MG132-induced RRTF1 stability suggested a role of the 26S proteasome pathway in its degradation. It has been widely accepted that E3 UBQ ligase binds to the UBQ conjugating enzyme E2 and a substrate protein, which results in ubiquitylation and degradation through the 26S proteasome pathway (Hua and Vierstra, 2011). CULLIN3 (CUL3)-based really interesting new gene (RING) E3 ligases (CRL3) are composed of the scaffolding subunit CUL3 protein, the RING-finger protein RING-Box protein 1 (RBX1), which binds to the C-terminal region of CUL3, and the N-terminal part of CUL3, which binds to proteins with a BTB/POZ domain (Hua and Vierstra, 2011). The BPM family contains a MATH domain located in the N-terminal region and a BTB/POZ fold in the C-terminal region (Weber and Hellmann, 2009). It has been shown that BPM proteins interact with AP2/ERF TFs, such as RELATED TO APETALA2.4 (RAP2.4) and WRINKLED1 (WRI1) in the MATH domain (Weber and Hellmann, 2009; Chen et al., 2013). In addition, it was shown that the degradation of WRI1 by the 26S proteasome depends on the CRL3BPM E3 ligase in fatty acid metabolism (Chen et al., 2013). In this study, we confirmed the interactions between RRTF1 and the MATH domain of BPM proteins, and the stability of RRTF1 is controlled by CRL3BPM E3 ligase, which is in agreement with the instability of WRI1, mediated by a CRL3BPM E3 ligase (Chen et al., 2013).

In addition to AP2/ERF family TFs, the bHLH family TFs have also been involved in JA-regulated plant growth and environmental adaptation. It has been widely accepted that the bHLH TFs MYCs are key transcriptional activators of JA-mediated gene expression and have central roles in the plant JA signaling pathway. More recently, BPM1, BPM2, BPM3, and BPM4 have been shown to interact with MYC2 and MYC3 (Chico et al., 2020). CRL3BPM E3 ligase targets MYCs for ubiquitination and degradation. However, knocking down BPM function decreases the ubiquitination levels of MYCs, thus increasing MYC stability and JA-regulated gene expression (Chico et al., 2020). Here, we also found that knocking down BPM1 and BPM3 function significantly promoted RRTF1 accumulation (Figure 5C) and increased JA-regulated DTX18 gene expression (Figure 6D) in bpm1/3 double mutants. Therefore, quantification of ubiquitination levels of RRTF1–HA in WT and bpm1/3 double mutants remains to be addressed in the future. In addition, JA stabilizes the BPM3 protein even though BPM gene expression is not regulated by JA (Chico et al., 2020). In contrast to BPM3, JA does not affect the BPM6 stability (Chico et al., 2020). It has been reported that the MATH domain determines the interaction of BPM proteins with their substrates (Weber and Hellmann, 2009; Chen et al., 2013). In our experiments, RRTF1 interacts with the MATH domain of BPM1 and BPM3 but not with BPM2, BPM4, BPM5, and BPM6 (Supplemental Figure S9), indicating that BPMs may share overlapping but not fully redundant functions. Therefore, we postulate that BPM proteins serve as potential regulators affecting the transcriptional activity and protein stability of different types of TFs in plants. It would be interesting to further identify the MATH domain interaction partners, which could provide the potential for discovering the multilayered regulatory mechanism that exists for BPM proteins and the JA signaling pathway.

In summary, we provide a new model to understand the fine-tuned regulation of ORA59 and RRTF1 in JA/ET and JA-induced HCAA accumulation (Figure 7). This model proposes that JA promotes CouAgm secretion onto the leaf surface via the stability of RRTF1, which is a target of CRL3BPM E3 ligase. It is fascinating that BPM proteins function as repressors of JA-responsive RRTF1 activity. Further comparative investigation of the regulatory mechanisms of different BPM–TF interactions will provide a better understanding of plant secondary metabolism.

Figure 7.

A proposed model of the role of ORA59 and RRTF1 in JA/ET and JA-induced HCAAs accumulation. In Arabidopsis plants, infection with necrotrophic pathogens could activate both JA and ET signaling pathways. ACT gene expression and CouAgm biosynthesis were synergistically induced by a combination of JA and ET. JA/ET induced the key positive regulator ORA59 TF, which directly binds to the GCC-box of the ACT gene promoter and activates the ACT gene expression for CouAgm biosynthesis. The transcript of RRTF1 gene is induced only by JA, and RRTF1 TF directly activates CouAgm secretion transporter DTX18 gene expression through binding its target site: GAGCCGGCAG. JA stabilized RRTF1 not only at the transcriptional induction, but also on the de novo synthesized protein. Without JAs, BPM proteins interact with RRTF1, BPM proteins function as substrate adaptors to CUL3-based E3-ligases CUL3BPM, docking of the BPM–RRTF1 complex to the CUL3BPM E3-ligase results in the degradation of RRTF1. However, the molecular mechanism of SA negatively affected ORA59 protein accumulation is unclear. Arrows indicate activation, T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, broken lines indicate that this regulation was not reported to date, and the question mark indicates that unknown factors or pathway. RRTFBS, RRTF1 binding site GAGCCGGCAG.

Materials and methods

Y1H assays

The promoter fragments of DTX18proI (−1 bp to −328 bp), DTX18proII (−329 bp to −705 bp), and DTX18proIII (−706 bp to −1,097 bp) were fused to a TATA box-His3 gene in plasmid pHIS3NX and integrated in the yeast (strain Y187) genome (Li et al., 2018). The JA-treated pACTII cDNA library was described in our previous report (Li et al., 2018). After the transformation of the JA-treated Arabidopsis cDNA library in the different DTX18pro yeast strains, cells were cultured on minimal medium lacking Leu and His (SD/-LH) together with 3 amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT, inhibitor of HIS3 enzyme activity; Sigma) concentrations ranging from 0 to 15 mM. The yeast strain carrying the DTX18proII bait showed background growth that was inhibited by the addition of 10 mM 3-AT. Plasmids were extracted from putative positive clones and digested with EcoRI and NcoI to release the cDNA from the pACTII plasmid. The plasmids were then run on a gel to determine the band size. The real positive clones were confirmed by retransformation and sequencing. Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

Full-length RRTF1, BPM1-6, and deletion derivatives RRTF1NT, RRTF1109CT, and BPM1-MATH were inserted into pACT2 or pAS2.1 vectors (Zhou et al., 2015). Cotransformation of pAS2.1-RRTF1 and 14-d-old Arabidopsis seedling cDNA libraries, or any bait and prey plasmids, was performed in the yeast strain PJ64-4A as previously described (Zhou et al., 2015). The positive colonies could grow on SD/-LW(Trp)H selection medium containing 15-mM 3-AT. A liquid culture β-galactosidase (arbitrary units) assay was performed on the transformed yeasts after 5 d of growth as described in the Yeast Protocols Handbook (Clontech). All primer sequences are presented in Supplemental Table S4, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

EMSA

To produce His-tagged proteins, PCR amplified RRTF1 was cloned in frame in front of the His-tag open reading frame of expression vector pASK-IBA45Plus (IBA Biotechnology, Göttingen, Germany). These plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21-(DE3) pLysS (Novagen). Protein expression, extraction, and purification were conducted as previously described (Zhou et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). The DTX18 promoter fragment II and its mutants were labeled by biotin. EMSA reaction mixtures contained 0.5 μg of purified protein, gel shift binding buffer, 2-nM biotin-labeled fragments or 10- or 100-fold excess of unlabeled fragments. The light shift chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Fisher) was used to perform EMSAs as described by the manufacturer. Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

ChIP-qPCR and qRT-PCR assay

HA-tagged RRTF1 or HA-tagged ORA59 was expressed in Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts and crossed linked to DNA as described previously (Li et al., 2018). Immunoprecipitation of chromatin-bound proteins was performed with HA antibody (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). qPCR was carried out using primers designed on the flanking sequence of the RRTF1-binding sites in the DTX18 promoter. The DTX18 gene and promoter region of UBQ10 were used as negative controls. ChIP assays were carried out as described previously (Zhou et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis (Revert Aid first-strand cDNA synthesis kit; Fermentas) were performed following the manufacturer’s guidelines, and qRT-PCR was performed as described earlier (Zhou et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). The qPCR primers for RRTF1, ACT, DTX18, PDF1.2, Bcactin, and Bcpg1 were used as previously described (Cai et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

Arabidopsis protoplast transactivation assays and GFP observation

The full-length RRTF1, ORA59, and BPM1 were inserted under the CaMV 35S promoter (effector plasmid), while DTX18FLpro was fused to GUS and GFP to generate the reporter plasmid using GusXX (Töpfer et al., 1987). Arabidopsis cell suspension protoplasts were cotransfected with 2-μg effector plasmid and 2-μg reporter plasmid. Arabidopsis cell suspension or leaf protoplast transformation and GUS activity assays were performed as previously described (Schirawski et al., 2000; He et al., 2007). GFP images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope equipped with a bandpass emission filter of 505–530 nm and an argon laser line of 488 nm (excitation). Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

BiFC

RRTF1, BPM1, and BPM1–MATH were inserted in pRTL2-YNEE (nYFP-) or pRTL2-HAYC (-cYFP) to generate fusion proteins. Cotransformation or transformation with 5 μg each of plasmids carrying C-terminal YFP-fused protein and N-terminal YFP-fused protein and nuclear marker (RFP) into Arabidopsis protoplasts were introduced by PEG-mediated transfection as previously described (Schirawski et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2017). Microscopy images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM780 confocal laser scanning microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software (Abràmoff et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2017). To detect the TagRFP signal, a 543-nm laser and a 560/615-nm bandpass filter were used. YFP was visualized using an argon 514-nm laser and a 530–600-nm bandpass filter. Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

Plant materials and growth conditions

Loss of function (SALK_150614) and overexpression (CS2102255) lines of locus At4g34410 (RRTF1) were obtained from the SALK Institute (http://signal.salk.edu/tdnaprimers.2.html). Pollen from homozygous bpm1 (At5g19000, SALK_035684) plants was used to pollinate emasculated homozygous bpm3 (At2g39760, SALK_032390) flowers to generate bpm1/3 double homozygous plants. The 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 plants were generated from a cross between 35S::ORA59 plants (Li et al., 2018) and 35S::RRTF1 plants (Bahieldin et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2014). The XVE::ORA59/ora59 plants were generated from a cross between XVE::ORA59 plants and ora59 mutant plants (Li et al., 2018). The 35S::ORA59-HA/bpm1bpm3 plants were generated from a cross between 35S::ORA59-HA plants (Li et al., 2018) and bpm1bpm3 double mutant plants. The coi1-1 and ein2-1 mutant plants were used in our previous work (Li et al., 2018). For plant hormones and proteasome inhibitor treatment, 2-week-old seedlings were treated with 50-μM JA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) or 0.05% DMSO, 1-mM ethephon (E), or a combination of both (E/JA), 50-μM MG132 or 2.5-μM Carfilzomib (PR-171) at different time points.

Botrytis cinerea pathogen assay

The B. cinerea 38B1 (isolated from Solanum lycopersicum) culture was developed as described previously (Broekaert et al., 1990). Spores were collected and resuspended in half-strength potato dextrose broth to a final density of 105 spores mL−1. For Botrytis inoculation, 3 µL of inocula (7.5 × 105/mL B. cinerea spores) was dropped on four mature leaves of each plant (4-week-old, 50 plants per genotype), which were kept at 100% RH throughout the experiment. Disease incidence was assessed after three days of inoculation. Disease ratings or classes were assigned based on the severity of the disease symptoms and lesion size: I, no visible symptoms; II, spreading lesion with or without a chlorotic halo; and III, spreading lesion with extensive tissue maceration. To observe Bcpg1 gene expression levels during infection, B. cinerea-infected leaf discs were punched with a 1-cm-diameter cork borer at five time points (0.5, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hpi), with six leaves (three inoculated biological replicates plus three mock-inoculated controls) per time point. Leaf samples were collected for RNA extraction.

Immunoblot analysis

The full-length RRTF1 was inserted into pTH2 under the CaMV 35S promoter to generate the RRTF1–GFP protein construct. Protein was extracted from transformed Arabidopsis protoplasts as described previously (Zhou et al., 2015, 2016). Total protein was extracted from 14-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings used for the study using 100-mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 5-mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5-mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 10-mM dithiothreitol, 150-mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, and complete protease inhibitors (Roche). Protein extracts were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, USA). The western blots were performed with anti-GFP, HA, and actin antibodies as described previously (Zhou et al., 2016). Supplemental Table S1 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

In vitro pull-down assay and coimmunoprecipitation

For in vitro pull-down, RRTF1 was inserted in pASK-IBA45plus, and BPM1 and BPM2 were inserted in pASK-IBA45 plus to produce HA-tagged and Strep-tagged proteins in E. coli BL21-(DE3) pLysS (Novagen), respectively. Proteins were purified using Strep-tactin sepharose (IBA) and anti-HA agarose beads (Thermo Scientific). For CoIP, the total protein was extracted from 14-d-old 35S::RRTF1–HA transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings using 50-mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 400-mM sucrose, and 2.5-mM EDTA. Recombinant His-BPM1 was expressed in E. coli BL21-(DE3) and purified using Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen) as previously described (Zhou et al., 2015, 2016). Three micrograms of His-BPM1 protein was immobilized onto 40 μL of Ni-NTA agarose beads (Qiagen). Subsequently, 25 μg of seedling protein extracts from 35S::RRTF1–HA transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings were added to the immobilized His-BPM1 in independent reactions and incubated for 2 h at 4°C in the CoIP buffer as previously described (Zhou et al., 2015, 2016). Next, the beads were washed three times and samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and subsequently probed with anti-HA and anti-His antibodies. Pull-down assays were performed as described previously (Zhou et al., 2016). Supplemental Table S4 shows the sequences of all the primers used in this study, and all constructed plasmids were sequenced.

Measurement of CouAgm

The isolation and quantification of CouAgm in leaves or in droplets of the inoculum of different genotypes were carried out using LC–MS as previously described (Dobritzsch et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). For the CouAgm measurement in droplets, each tested genotype conducts sextuplicate experiments, and each experiment is the mixture of three independent lines.

Statistical analysis

The significance of the data was assessed using Student’s t-test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Accession numbers

Sequence data for the genes described in this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: RRTF1 (At4g34410), ORA59 (At1g06160), BPM1 (At5g19000), BMP2 (At3g06190), BPM3 (At2g39760), BPM4 (At3g03740), BPM5 (At5g21010), BPM6 (At3g43700), DTX18 (At3g23550), ACT (At5g61160), PDF1.2 (At5g44420), UBQ10 (At4g05320), and Bcpg1 (XM_001550027).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Promoter sequence of the DTX18 gene in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phenotype analysis of ora59/rrtf1 mutant and 35S::RRTF1 and 35S::ORA59;35S::RRTF1 overexpressed Arabidopsis lines.

Supplemental Figure S3. Expression of the Arabidopsis defense-related genes PDF1.2 and ORA59 induced by B. cinerea as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR.

Supplemental Figure S4. Relative transcript levels of the Botrytis polygalacturonase gene Bcpg1 in different genotypes during infection with B. cinerea.

Supplemental Figure S5. The CouAgm levels were determined in whole plants of different genotypes by LC–MS.

Supplemental Figure S6. CouAgm levels were determined in droplets of the inoculum of different genotypes by LC–MS (Replicates 2 and 3).

Supplemental Figure S7. Measurement of CouAgm levels in indicated genotypes by LC–MS.

Supplemental Figure S8. Estradiol-induced RRTF1 gene expression in different genotypes as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR.

Supplemental Figure S9. RRTF1 interacts with BPM family proteins in quantitative Y2H assays.

Supplemental Figure S10. BPM1 interacts with the RRTF1 N-terminus in quantitative Y2H assays.

Supplemental Figure S11. Expression of PDF1.2 and RRTF1 in all genotypes as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR.

Supplemental Figure S12. Relative transcript levels of the Botrytis polygalacturonase gene Bcpg1 in WT, bpm1, bpm3, and bpm1/3 mutant plants during infection with B. cinerea.

Supplemental Table S1. Classification of the positive clones in the yeast one-hybrid system.

Supplemental Table S2. Distribution of disease severity classes in different genotypes.

Supplemental Table S3. Distribution of disease severity classes in WT and bpm1/3 mutant lines.

Supplemental Table S4. Primers used in this study.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, project PlantaSYST (SGA No 739582 under FPA No. 664620), and the BG05M2OP001-1.003-001-C01 project, financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the “Science and Education for Smart Growth” Operational Program.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

M.Z., M.I.G., and B.X. conceived and supervised the research. J.L., Y.M., K.Z., Q.L., and S.L conducted the experiments. J.L., Y.M., and K.Z. analyzed the data. J.L., Y.M., and M.Z. wrote the paper.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys) is: Meiliang Zhou (zhoumeiliang@caas.cn).

References

- Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton Int 11:36–42 [Google Scholar]

- Bahieldin A, Atef A, Edris S, Gadalla NO, Ali HM, Hassan SM, Al-Kordy MA, Ramadan AM, Makki RM, Al-Hajar AS, et al. (2016) Ethylene responsive transcription factor ERF109 retards PCD and improves salt tolerance in plant. BMC Plant Biol 16:216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahieldin A, Atef A, Edris S, Gadalla NO, Ramadam AM, Hassan SM, Attas SG, Al-Kordy MA, Al-Hajar AS, Sabir JS, et al. (2018) Multifunctional activities of ERF109 as affected by salt stress in Arabidopsis. Sci Rep 8:6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti CE, Xie D, Turner JG (1995) COI1-dependent expression of an Arabidopsis vegetative storage protein in flowers and siliques and in response to coronatine or methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol 109:567–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekaert WF, Terras FRG, Cammue BPA, Vanderleyden J (1990). An automated quantitative assay for fungal growth. FEMS (Fed Eur Microbiol Soc) Microbiol Lett 69:55–60 [Google Scholar]

- Cai XT, Xu P, Zhao PX, Liu R, Yu LH, Xiang CB (2014) Arabidopsis ERF109 mediates cross-talk between jasmonic acid and auxin biosynthesis during lateral root formation. Nat Commun 5:5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos L, Lisón P, López-Gresa MP, Rodrigo I, Zacarés L, Conejero V, Bellés JM (2014) Transgenic tomato plants overexpressing tyramine N-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase exhibit elevated hydroxycinnamic acid amide levels and enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 27:1159–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Lee JH, Weber H, Tohge T, Witt S, Roje S, Fernie AR, Hellmann H (2013) Arabidopsis BPM proteins function as substrate adaptors to a cullin3-based E3 ligase to affect fatty acid metabolism in plants. Plant Cell 25:2253–2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chico JM, Lechner E, Fernandez-Barbero G, Canibano E, García-Casado G, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Hammann P, Zamarreño AM, García-Mina JM, Rubio V, et al. (2020) CUL3BPM E3 ubiquitin ligases regulate MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 stability and JA responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:6205–6215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Goossens A, Solano R (2016) Redundancy and specificity in jasmonate signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 33:147–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CH, Zheng HQ, Wu NY, Chien CH, Huang HD, Lee TY, Chiang-Hsieh YF, Hou PF, Yang TY, Chang WC (2016) PlantPAN 2.0: an update of plant promoter analysis navigator for reconstructing transcriptional regulatory networks in plants. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D1154–D1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritzsch M, Lübken T, Eschen-Lippold L, Gorzolka K, Blum E, Matern A, Marillonnet S, Böttcher C, Dräger B, Rosahl S (2016) MATE transporter-dependent export of hydroxycinnamic acid amides. Plant Cell 28:583–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Calvo P, Chini A, Fernández-Barbero G, Chico JM, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Geerinck J, Eeckhout D, Schweizer F, Godoy M, Franco-Zorrilla JM, et al. (2011) The Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factors MYC3 and MYC4 are targets of JAZ repressors and act additively with MYC2 in the activation of jasmonate responses. Plant Cell 23:701–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Shan L, Sheen J (2007) The use of protoplasts to study innate immune responses. Methods Mol Biol 354:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GA, Major IT, Koo AJ (2018) Modularity in jasmonate signaling for multistress resilience. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69:387–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z, Vierstra RD (2011) The cullin-RING ubiquitin-protein ligases. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62:299–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C, Zhao P, Seo JS, Mitsuda N, Deng S, Chua NH (2015) PLANT U-BOX PROTEIN10 regulates MYC2 stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27:2016–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang K, Meng Y, Hu J, Ding M, Bian J, Yan M, Han J, Zhou M (2018) Jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling coordinates hydroxycinnamic acid amides biosynthesis through ORA59 transcription factor. Plant J 95:444–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo O, Piqueras R, Sanchez-Serrano JJ, Solano R (2003) ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell 15:165–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M, Johnson JM, Hieno A, Tokizawa M, Nomoto M, Tada Y, Godfrey R, Obokata J, Sherameti I, Yamamoto YY, et al. (2015) High REDOX RESPONSIVE TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR1 levels result in accumulation of reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis thaliana shoots and roots. Mol Plant 8:1253–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroi A, Ishihara A, Tanaka C, Ishizuka A, Takabayashi J, Miyoshi H, Nishioka T (2009) Accumulation of hydroxycinnamic acid amides induced by pathogen infection and identification of agmatine coumaroyltransferase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 230:517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CM, Van der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC (2012) Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28:489–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pré M, Atallah M, Champion A, De Vos M, Pieterse CM, Memelink J (2008) The AP2/ERF domain transcription factor ORA59 integrates jasmonic acid and ethylene signals in plant defense. Plant Physiol 147:1347–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T, Wang J, Huang H, Liu B, Gao H, Liu Y, Song S, Xie D (2015) Regulation of jasmonate-induced leaf senescence by antagonism between bHLH subgroup IIIe and IIId factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27:1634–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirawski J, Planchais S, Haenni AL (2000) An improved protocol for the preparation of protoplasts from an established Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension culture and infection with RNA of turnip yellow mosaic tymovirus: a simple and reliable method. J Virol Methods 86:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer F, Bodenhausen N, Lassueur S, Masclaux FG, Reymond P (2013) Differential contribution of transcription factors to Arabidopsis thaliana defense against Spodoptera littoralis. Front Plant Sci 4:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K, van Tuinen A, van Kan JAL, Wolters AA, Jacobsen E, Visser RGF, Bai Y (2017) Silencing of DND1 in potato and tomato impedes conidial germination, attachment and hyphal growth of Botrytis cinerea. BMC Plant Biol 17:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Töpfer R, Matzeit V, Gronenborn B, Schell J, Steinbiss HH (1987) A set of plant expression vectors for transcriptional and translational fusions. Nucleic Acids Res 15:5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does D, Leon-Reyes A, Koornneef A, Van Verk MC, Rodenburg N, Pauwels L, Goossens A, Körbes AP, Memelink J, Ritsema T, et al. (2013) Salicylic acid suppresses jasmonic acid signaling downstream of SCFCOI1-JAZ by targeting GCC promoter motifs via transcription factor ORA59. Plant Cell 25:744–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Moerkercke A, Duncan O, Zander M, Šimura J, Broda M, Vanden Bossche R, Lewsey MG, Lama S, Singh KB, Ljung K, et al. (2019) A MYC2/MYC3/MYC4-dependent transcription factor network regulates water spray-responsive gene expression and jasmonate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:23345–23356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Feussner I (2018) The oxylipin pathways: biochemistry and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69: 363–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H, Bernhardt A, Dieterle M, Hano P, Mutlu A, Estelle M, Genschik P, Hellmann H (2005) Arabidopsis AtCUL3a and AtCUL3b form complexes with members of the BTB / POZ-MATH protein family. Plant Physiol 137:83–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H, Hellmann H (2009) Arabidopsis thaliana BTB/POZ-MATH proteins interact with members of the ERF/AP2 transcription factor family. FEBS J 276: 6624–6635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye BB, Shang GD, Pan Y, Xu ZG, Zhou CM, Mao YB,, Bao N, Sun L, Xu T, Wang JW (2020) AP2/ERF transcription factors integrate age and wound signals for root regeneration. Plant Cell 32:226–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander M, Lewsey MG, Clark NM, Yin L, Bartlett A, Saldierna Guzmán JP, Hann E, Langford AE, Jow B, Wise A, et al. (2020) Integrated multi-omics framework of the plant response to jasmonic acid. Nat Plants 6:290–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei A, Körbes AP, Younessi P, Montiel G, Champion A, Memelink J (2011) Two GCC-boxes and AP2/ERF domain transcription factor ORA59 in jasmonate/ethylene- mediated activation of the PDF1.2 promoter in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol 75:321–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Memelink J (2016) Jasmonate-responsive transcription factors regulating plant secondary metabolism. Biotechnol Adv 34:441–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Sun Z, Li J, Wang D, Tang Y, Wu Y (2016) Identification of JAZ1-MYC2 complex in Lotus corniculatus. J Plant Growth Regul 35: 440–448 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Sun Z, Ding M, Logacheva MD, Kreft I, Wang D, Yan M, Shao J, Tang Y, Wu Y, Zhu X (2017) FtSAD2 and FtJAZ1 regulate activity of the FtMYB11 transcription repressor of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Fagopyrum tataricum. New Phytol 216:814–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Sun Z, Wang C, Zhang X, Tang Y, Zhu X, Shao J, Wu Y (2015) Changing a conserved amino acid in R2R3-MYB transcription repressors results in cytoplasmic accumulation and abolishes their repressive activity in Arabidopsis. Plant J 84:395–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.