Nonphotosynthetic holoparasites exploit flexible targeting of phylloquinone biosynthesis to facilitate plasma membrane redox signaling.

Abstract

Nonphotosynthetic holoparasites exploit flexible targeting of phylloquinone biosynthesis to facilitate plasma membrane redox signaling. Phylloquinone is a lipophilic naphthoquinone found predominantly in chloroplasts and best known for its function in photosystem I electron transport and disulfide bridge formation of photosystem II subunits. Phylloquinone has also been detected in plasma membrane (PM) preparations of heterotrophic tissues with potential transmembrane redox function, but the molecular basis for this noncanonical pathway is unknown. Here, we provide evidence of PM phylloquinone biosynthesis in a nonphotosynthetic holoparasite Phelipanche aegyptiaca. A nonphotosynthetic and nonplastidial role for phylloquinone is supported by transcription of phylloquinone biosynthetic genes during seed germination and haustorium development, by PM-localization of alternative terminal enzymes, and by detection of phylloquinone in germinated seeds. Comparative gene network analysis with photosynthetically competent parasites revealed a bias of P. aegyptiaca phylloquinone genes toward coexpression with oxidoreductases involved in PM electron transport. Genes encoding the PM phylloquinone pathway are also present in several photoautotrophic taxa of Asterids, suggesting an ancient origin of multifunctionality. Our findings suggest that nonphotosynthetic holoparasites exploit alternative targeting of phylloquinone for transmembrane redox signaling associated with parasitism.

Introduction

Phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is a membrane-bound naphthoquinone derivative known to function as an essential electron acceptor in photosystem I (PSI; Brettel et al., 1986). Phylloquinone also serves as an electron carrier for protein disulfide bond formation crucial for PSII assembly (Furt et al., 2010; Karamoko et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2013). Accordingly, phylloquinone is found predominantly in thylakoids, and most phylloquinone-deficient Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants are seedling-lethal or growth-impaired (reviewed in Gilles et al., 2016). A sizable phylloquinone pool is stored in plastoglobuli attached to thylakoid membranes (Lohmann et al., 2006; Eugeni Piller et al., 2012). A small portion of leaf phylloquinone is present as fully reduced quinol, with potential redox function during senescence or dark growth (Oostende et al., 2008).

The eubacterial cognate menaquinone (vitamin K2) functions in respiratory electron transport across the cell membrane (Nowicka and Kruk, 2010). A similar role for phylloquinone in plant plasma membrane (PM) electron transport has also been proposed, and phylloquinone has been detected in PM preparations of maize (Zea mays) roots (Lüthje et al., 1998; Lochner et al., 2003). UV-irradiation of cultured carrot (Daucus carota) cells destroyed phylloquinone, and blocked transmembrane electron transport until restoration by phylloquinone feeding (Barr et al., 1992). The PM redox activities can be inhibited by phylloquinone antagonists, dicumarol and warfarin, whereas applications of menadione (vitamin K3) or phylloquinone restore transmembrane electron flow (Döring et al., 1992a, 1992b; Lüthje et al., 1992). Despite these early reports, however, molecular evidence that directly supports PM-targeting of phylloquinone remains elusive.

The phylloquinone biosynthetic pathway has an endosymbiotic origin, comprising a series of “Men” proteins named after their eubacterial homologs in the menaquinone biosynthesis operon (Figure 1). A notable exception is the penultimate enzyme (step 9, Figure 1A) of the flavin-containing NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (FQR/NQR/QR) family recently shown to be necessary for phylloquinone biosynthesis in plants and cyanobacteria (Eugeni Piller et al., 2011; Fatihi et al., 2015). The corresponding enzyme in A. thaliana, type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenase C1 (NDC1), was first identified as a mitochondrial respiratory chain component (Michalecka et al., 2003), but later was also found to target to the chloroplast (Carrie et al., 2008), with additional functions in plastoquinone reduction and redox cycling of α-tocopherols in plastoglobuli (Eugeni Piller et al., 2011). Intracellular compartmentalization is a hallmark of phylloquinone biosynthesis, with the early (steps 1–4, Figure 1A) and late pathway steps (8–10) occurring in chloroplasts, and the intermediate steps (5–7) in peroxisomes (Babujee et al., 2010). Even within the chloroplast, the three terminal steps shuttle between envelope membranes (MenA, Schultz et al., 1981), plastoglobuli (NDC1, Eugeni Piller et al., 2011), and thylakoid membranes (MenG, Kaiping et al., 1984), highlighting the complex trafficking involved in this pathway.

Figure 1.

Phylloquinone biosynthesis in parasitic plants. A, A simplified phylloquinone biosynthetic pathway from top to bottom as numbered and color-coded by their predicted subcellular localization. B, Expression profiles of phylloquinone genes during parasitic plant development. Gene order is the same as in (A), and Y-axis is shown on the right. Developmental stages are as reported (Yang et al., 2015): 0, imbibed seeds; 1, germinated seeds/radicles; 2, HIF-treated seedlings; 3, haustoria, pre-vascular connection; 4.1, haustoria, post-vascular connection; 6.1, leaves/stems; 6.2, floral buds. Data from alternative gene candidates for the penultimate step are shown on the lower right panels, with grey dashed/dotted lines denoting the scale. C, HPLC detection of phylloquinone in germinated P. aegyptiaca seeds (top panel), and with spiked authentic standard (lower panel). Menaquinone (MK-4) was included as a reference. D, HPLC detection of phylloquinone in A. thaliana seed (top panel), and with authentic standard (lower panel)

We have observed in multiple photosynthetic taxa that phylloquinone-specific genes such as MenA and MenG have measurable expression in heterotrophic tissues where photosynthetic genes are barely detected. To ascertain a noncanonical phylloquinone pathway, we exploited parasitic plants as a photosynthesis-free study system. Among angiosperm parasite families, only the Orobanchaceae contains species that span the full spectrum of photosynthetic capacities, and for which rich transcriptomic resources are available (Westwood et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2015). Of particular interest are obligate holoparasites, such as Phelipanche aegyptiaca, that are devoid of photosynthetic activity and obtain all of their carbon from their hosts. In contrast, obligate (e.g. Striga hermonthica) and facultative (e.g. Triphysaria versicolor) hemiparasites are partially or fully photosynthetic. Here, we report on the biosynthesis and PM targeting of phylloquinone in the nonphotosynthetic P. aegyptiaca. Gene network analysis revealed a strong link between phylloquinone and cellular oxidation–reduction processes implicated in parasitic invasion and haustorium development. We propose that parasitic plants exploit alternative phylloquinone targeting for PM redox regulation associated with parasitism.

Results

Phelipanche aegyptiaca contains the full complement of phylloquinone biosynthetic genes

Phylloquinone pathway protein sequences of Mimulus guttatus, a photoautotroph from Phrymaceae sister to Orobanchaceae, were searched against transcript assemblies available from the Parasitic Plant Genome Project (Yang et al., 2015). Full-length coding sequences were identified for PaICS and PaMenE genes in P. aegyptiaca, along with partial assemblies of other phylloquinone pathway genes. Fragmented transcripts may represent nonfunctional relics of genes undergoing degeneration or may reflect technical limitations of de novo assembly that prevented identification of the full complement of phylloquinone biosynthetic genes. The recovery of full-length PaICS and PaMenE transcripts strongly favored the latter scenario.

We addressed the fragmented assembly challenge by developing a pipeline called parallelized local assembly of sequences (PLAS) that combines reference-guided mapping (against the M. guttatus proteome in this case) with iterative de novo assembly for transcriptome reconstruction. When applied to the RNA-seq datasets of parasitic plants, we successfully recovered full-length transcripts with intact ORFs for all known phylloquinone genes from the holoparasite (Supplemental Data Set S1). These transcripts were detected at moderate to high levels during P. aegyptiaca development, except PaNDC1—the latest addition to the pathway—which was poorly expressed throughout the holoparasite (Figure 1B). PHYLLO, MenE and DHNAT (dihydroxynaphthoate thioesterase) transcripts were detected at similar levels in the three parasites. In contrast, the expression patterns of ICS, MenB, MenA, and MenG differed between P. aegyptiaca and its photosynthetic relatives S. hermonthica and T. versicolor, especially in response to germination stimulants and haustorium-inducing factors (HIFs) during early development (stages 1–3, Figure 1B). However, the apparent lack of PaNDC1 expression weakened support for a functioning phylloquinone pathway. Alternatively, retention and expression of the other seven phylloquinone pathway genes may point to a different pathway configuration at the penultimate step in the holoparasite.

We therefore sought to substantiate phylloquinone production in P. aegyptiaca, focusing on early development prior to host exposure and haustorium initiation to avoid potential contamination from the photosynthetic host. HPLC analysis confirmed the presence of phylloquinone in germinated P. aegyptiaca seeds (Figure 1C), with an estimated level of 0.05 ± 0.02 pmol/mg dry weight (n = 3). For reference, phylloquinone levels in A. thaliana seeds were 0.12 ± 0.03 pmol/mg dry weight (n = 3; Figure 1D). The result lent support to phylloquinone biosynthesis in the holoparasite. We next examined other candidates that could participate in the reduction of demethylphylloquinone at the penultimate step (step 9). Besides the multifunctional NDC1 (Fatihi et al., 2015), menadione-reducing activities have been demonstrated for two other groups of evolutionarily conserved QR, one represented by T. versicolor TvQR2 (Wrobel et al., 2002) and A. thaliana AtFQR1 (Laskowski et al., 2002) of the type IV family (Patridge and Ferry, 2006), and the other by soybean (Glycine max) GmNQR of the DT-diaphorase type (Schopfer et al., 2008). PaNQR transcripts were detected at moderate levels throughout P. aegyptiaca development (Figure 1B), but they were not coexpressed with any phylloquinone pathway genes (see below). In contrast, PaQR2 was well expressed during early stages of P. aegyptiaca development like other phylloquinone genes (Figure 1B). Type IV QR2 has in fact been implicated in reduction of menaquinone and phylloquinone to their respective quinols in the manually curated KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) reference pathways (Kanehisa et al., 2018). The structural similarity between phylloquinone and its demethylated precursor, and the reported substrate promiscuity of the orthologous TvQR2 (Wrobel et al., 2002) lent further support to PaQR2 involvement in the penultimate step of P. aegyptiaca phylloquinone biosynthesis.

Phylloquinone biosynthesis is redirected to the PM in the holoparasite

Identification of the phylloquinone pathway in P. aegyptiaca with vestigial plastids raised the possibility that the biosynthetic enzymes exhibit alternative targeting with nonplastidial function(s). Protein subcellular localization analyses predicted plastid- and peroxisome-targeting of early (PaICS and PaPHYLLO) and intermediate (PaMenE, PaMenB, and PaDHNAT) pathway steps, respectively, similar to their orthologs in photoautotrophic taxa (Supplemental Table S1 and Supplemental Figures S1–S3). However, the predicted polypeptides of late pathway steps PaMenA and PaMenG are truncated at the N-terminus relative to their photoautotrophic orthologs (Figure 2;Supplemental Figures S4–S5) and scored poorly for plastid-targeting with multiple prediction programs (Figure 2A). The N-truncation of PLAS-derived PaMenA and PaMenG transcripts was independently confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) cloning and sequencing (GenBank accession numbers MT506520 and MT506521), and by identification of N-truncated orthologs from other species (see below).

Figure 2.

Characterization of MenA and MenG. A, Plastid-targeting prediction of MenA and MenG polypeptides from various species. Heatmaps show prediction strengths above the 50th percentile of each method. Those with a high prediction score from at least one program are deemed potentially plastidial, as not all methods accurately predict experimentally characterized plastidial proteins (asterisks). Introns are not drawn to scale. CDS, coding sequence; UTR, untranslated region. B, Transmembrane domain prediction of AtMenA (green line denoting the transit peptide) and PaMenA2 (shifted x-axis for domain alignment). C–D, Confocal images of PaMenA2-GFP (C) and PaMenG2-GFP (D) colocalization with a plasma membrane marker AtPIP2A-mCherry. Scale bars = 20 µm. E, HPLC analysis of E. coli ΔmenG mutant strain JW5581 expressing PaMenG2 or the EcMenG control. (D)MK-8, (demethyl)menaquinone-8. F–G, Bayesian phylogeny of MenA and MenG from representative Asterids and two Rosids. Af, Aphyllon fasciculata; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Ca, Conopholis americana; Lp, Lindenbergia philippensis; Migut, Mimulus guttatus; Pa, Phelipanche aegyptiaca; Potri, Populus trichocarpa; Rg, Rehmannia glutinosa; Solyc, Solanum lycopersicum; Sh, Striga hermonthica; Tv, Triphysaria versicolor; Vt, Verbascum thapsus. Branch support is shown for major nodes. Scale indicates the number of amino acid substitutions per site

PaMenA is predicted as an integral protein with multiple transmembrane helices in a topology similar to that of AtMenA (Figure 2B). The absence of an N-terminal plastid-targeting peptide in PaMenA suggests its localization to other cellular membranes. The penultimate PaQR2, like its photoautotrophic orthologs, also lacks plastid-targeting sequence (Supplemental Figure S6), which contrasts with the alternative NDC1s that are predicted plastidial (Supplemental Table S1). Indeed, PM association has been reported for A. thaliana, rice (Oryza sativa), and yeast (Candida albicans) QR2 orthologs (Marmagne et al., 2004; Natera et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015). These data suggest the post-peroxisomal steps are likely targeted to PM in P. aegyptiaca. We generated stably transformed Nicotiana benthamiana expressing 35S:PaMenA-GFP or 35S:PaMenG-GFP along with a PM marker 35S:AtPIP2A-mCherry (Nelson et al., 2007). Confocal imaging showed co-localization of PaMenA and PaMenG with the PM marker in transgenic roots (Figure 2, C and D), providing experimental support for alternative targeting of the N-truncated PaMenA and PaMenG in P. aegyptiaca.

The PM pathway has canonical activity and an ancient origin

The absence of the N-terminal transit signal is not expected to impact (mature) enzyme catalysis. Using PaMenG as a test case, we performed complementation experiments with the Escherichia coli ΔmenG mutant strain JW5581 (Baba et al., 2006). The E. coli MenG, also called UbiE, is a dual C-methyltransferase involved in both menaquinone and ubiquinone biosynthesis, and its mutation leads to over-accumulation of demethylmenaquinone (Lee et al., 1997). Constitutive expression of PaMenG in the mutant strain restored menaquinone production similar to the EcMenG-complemented control (Figure 2E). The data provide biochemical evidence for canonical activity of the N-truncated PaMenG.

Interestingly, distinct MenG1 and MenG2 genes encoding long (plastidial) and short (PM) isoforms, respectively, are present in both S. hermonthica and T. versicolor (Figure 2A), suggesting that the PM phylloquinone pathway may have evolved before the transition to parasitism. To strengthen this finding, we mined the One Thousand Plant Transcriptomes (1KP) database (Leebens-Mack et al., 2019) and identified several photoautotrophic species—all from Lamiales—that harbor both long and short isoforms of MenA and/or MenG, including Lindenbergia philippensis, Rehmannia glutinosa, and Verbascum thapsus. In contrast, only N-truncated short isoforms were found in two other Orobanchaceae holoparasites, Aphyllon (syn. Orobanche) fasciculata and Conopholis americana (Supplemental Figures S4–S5). Phylogenetic analysis clustered the plastidial and PM isoforms into distinct groups for both MenA and MenG (Figure 2, F and G), suggesting their origin from lineage-specific duplication events (hereafter, the PM-localized short isoforms are referred to as MenA2 and MenG2). Of note, transcripts encoding PM-targeted MenG2 were detected at higher levels than those encoding plastidial MenG1 in both S. hermonthica and T. versicolor (Figure 1B), suggesting divergent regulation of the two MenG isoforms in photosynthetic hemiparasites.

Photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic parasites exhibit distinct phylloquinone gene coexpression patterns

We detected high levels of coexpression among phylloquinone genes in the holoparasites, reminiscent of the patterns observed in photosynthetic taxa, including T. versicolor (Figure 3) [except for A. thaliana AtICSs and AtDHNATs involved in salicylic acid biosynthesis (Garcion et al., 2008) and peroxisomal β-oxidation (Cassin-Ross and Hu, 2014), respectively]. Interestingly, early- and late-pathway genes showed distinct coexpression patterns in the obligate hemiparasite S. hermonthica, perhaps indicative of dual involvement of those genes in plastidial and nonplastidial functions. To shed light on PM-phylloquinone functions, we extracted the top 500 most highly correlated transcripts for each phylloquinone gene except the alternative QR2 and NDC1. The union set contained 2,447, 3,677, and 3,930 unique transcripts for P. aegyptiaca, S. hermonthica, and T. versicolor, respectively. Interestingly, QR2 but not NDC1 was captured in all three networks. The smaller P. aegyptiaca gene set is consistent with stronger coexpression of phylloquinone genes when compared to S. hermonthica and T. versicolor (Figure 3, A–C). Subsets of gene ontology (GO)-annotated (biological process) transcripts (645, 1,199, and 1,173 for P. aegyptiaca, S. hermonthica, and T. versicolor, respectively) were then subjected to functional enrichment analysis. Transcripts associated with “photosynthesis” comprised 3%–4% GO-annotated transcripts in photosynthetic parasites but were negligible in P. aegyptiaca (Figure 3G). In contrast, transcripts associated with “oxidation–reduction process”, “protein phosphorylation”, and “defense response” were more enriched in P. aegyptiaca relative to S. hermonthica and T. versicolor (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Coexpression of phylloquinone genes. A–F, Coexpression patterns among phylloquinone biosynthetic genes, including multifunctional NDC1 and QR2, based on Gini correlation coefficient. Relevant genes or gene members involved in phylloquinone biosynthesis are boxed. The exceptions are A. thaliana AtICSs involved in salicylic acid biosynthesis for defense and AtDHNATs in peroxisomal β-oxidation (dashed box), besides phylloquinone biosynthesis. The corresponding Arabidopsis, Glycine, and Populus gene models are shown on the x-axis with shortened prefix for soybean (Gm = Glyma) and poplar (Pt = Potri). G, GO enrichments of phylloquinone-coexpressed genes defined as the union set of the top 500 most highly correlated transcripts for each phylloquinone gene. Only the top 10 categories are shown. Similar results were obtained using Gini correlation coefficient ≥0.8 to extract phylloquinone-coexpressed genes

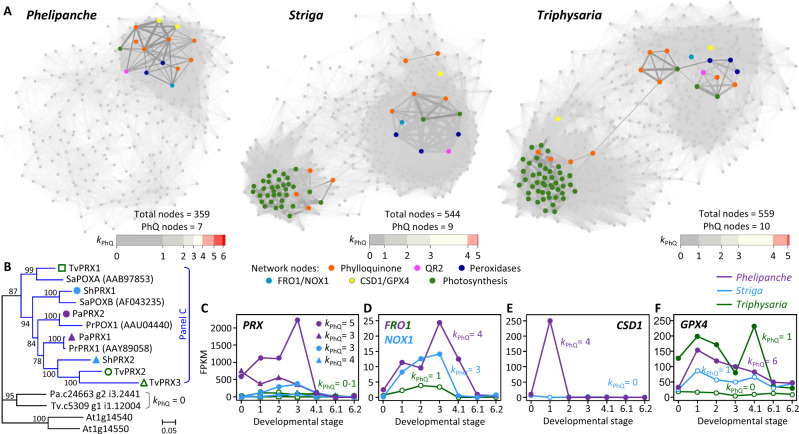

We focused on transcripts assigned to oxidation–reduction, defense, and photosynthesis GO terms for coexpression network analysis. Inclusion of orthologs from all three parasites resulted in 359, 544, and 559 nonredundant transcripts from P. aegyptiaca, S. hermonthica, and T. versicolor, respectively (Supplemental Data Set S2). Network visualization of coexpression patterns revealed striking differences (Figure 4). Two dense modules were detected for photosynthetic S. hermonthica and T. versicolor; one enriched with photosynthesis genes (Figure 4A, green nodes) and the other containing known parasitism genes (blue, magenta, and cyan nodes, see below). However, only one dense module containing parasitism genes was detected for the holoparasite. The phylloquinone genes (orange nodes) were highly interconnected with parasitism genes in the P. aegyptiaca network but were scattered over the two modules in S. hermonthica and T. versicolor networks, presumably reflecting dual functionality in these taxa. We ranked genes by the number of edges they shared with phylloquinone genes (referred to as kPhQ) in each network and observed a strong enrichment of phylloquinone-interconnected genes in the smaller P. aegyptiaca network. More than 23% of P. aegyptiaca nodes had a kPhQ =4–6 (i.e. connected with a majority of the seven phylloquinone genes). However, less than 3% of the S. hermonthica and T. versicolor nodes met the same criterion (kPhQ ≥5 of 9–10 phylloquinone genes), and only 10% and 15% of their respective nodes had a kPhQ ≥4 (Figure 4A, kPhQ bars).

Figure 4.

Phylloquinone gene coexpression networks. A, Network visualization of the three parasitic plants. Edge thickness reflects the coexpression strength. Key gene nodes are color-coded by pathway or family, and QR2 is colored differently from the other phylloquinone genes (NDC1 was not captured in any of the networks). Horizontal bars depict the distribution of nodes according to their connectivity with phylloquinone genes (kPhQ). B, Bayesian phylogeny of peroxidases (PRX). Orthologs of experimentally characterized PRXs are color-coded by species in the blue clade. Scale indicates the number of amino acid substitutions per site. C–F, Expression profiles of PRX (C), FRO1/NOX1 (D), CSD1 (E), and GPX4 (F) orthologs. Solid symbols denote phylloquinone-coexpressed genes (kPhQ ≥3), and others are shown in open symbols. Developmental stages are the same as in Figure 1

Phelipanche aegyptiaca phylloquinone gene networks associate parasitism with PM redox signaling

Several oxidoreductases known to be involved in parasitism were captured in the phylloquinone gene network of P. aegyptiaca. Root-specific apoplastic/secretory peroxidases (PRXs or POXs), including S. asiatica SaPOXA and SaPOXB and P. ramosa PrPOX1 and PrPRX1, have established roles in haustorium induction via generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidation of host cell wall-derived phenolics and quinones, such as 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone (DMBQ), as HIFs (Kim et al., 1998; González-Verdejo et al., 2006; Veronesi et al., 2007). The PRX orthologs (Figure 4B, blue clade) were abundantly expressed in P. aegyptiaca throughout seed germination and haustorium development (Figure 4C). The phylloquinone-coexpression strength (kPhQ) was highest in P. aegyptiaca, followed by S. hermonthica, but was not observed for T. versicolor PRXs, or for homologs in the neighboring clade of the phylogenetic tree (Figure 4, B and C). Thus, the phylloquinone-coexpression strength of the secretory PRXs appears to be positively correlated with parasitism.

Also implicated in parasitism are QR1 and QR2, depending on the species. QR1 is a chloroplast envelope protein of the ζ-crystalline type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase family involved in haustorium development of T. versicolor (Bandaranayake et al., 2010). However, QR2 but not QR1 is responsive to HIFs in S. asiatica and Phtheirospermum japonicum (Ishida et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2016), similar to the patterns observed for P. aegyptiaca and S. hermonthica (Figure 1B). QR1 was not captured in any of the phylloquinone subnetworks, whereas the phylloquinone-coexpression strength of QR2 was highest in P. aegyptiaca (kPhQ =4), followed by S. hermonthica (kPhQ =3) and T. versicolor (kPhQ =1; Figure 4A), similar to the secretory PRXs. These results suggest a link between phylloquinone biosynthesis and parasitism.

We next searched the P. aegyptiaca phylloquinone subnetwork for redox proteins known to participate in transmembrane electron transport (Bérczi and Møller, 2000; Keyes et al., 2000). Several flavocytochrome b superfamily proteins catalyze PM electron transport from cytosolic NAD(P)H to apoplastic acceptors, including NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX, also known as respiratory burst oxidase homologs) and ferric reductase oxidases (FRO; Bérczi and Møller, 2000; Jain et al., 2014). The P. aegyptiaca transcriptome lacked NOX, but contained an FRO (PaFRO1) orthologous to AtFRO4/AtFRO5 tandem duplicates that function as Cu-specific reductases at the root surface (Bernal et al., 2012). PaFRO1 transcript levels were highest in prehaustorial and haustorial tissues (Figure 4D), suggesting potential involvement in the PM redox system there. Interestingly, S. hermonthica harbors a NOX, but not FRO, perhaps indicative of lineage-specific transcriptome rewiring. Its counterpart in S. asiatica (SaNOX1) is indeed root-specific and HIF-responsive (Liang et al., 2016).

Electron transport chains are major sources of ROS, which are tightly controlled by antioxidant systems, such as Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases (Cu/Zn-SOD or CSD) and glutathione peroxidases (GPX; Mittler et al., 2004; Margis et al., 2008). P. aegyptiaca PaCSD1 (kPhQ =4) and PaGPX4 (kPhQ =6) were highly coexpressed with phylloquinone genes (Figure 4, E and F). CSD1 is a known leaderless secretory protein frequently detected in apoplastic/secreted proteomes (Cheng et al., 2009; Pechanova et al., 2010), while GPX4 orthologs in A. thaliana (AtGPX4/5 genome duplicates) were recently shown to be PM-anchored based on redox-sensitive GFP fusions (Attacha et al., 2017). Thus, besides the secretory PaPRXs, PaCSD1, and PaGPX4 may also participate in apoplastic redox modulation in the holoparasite. In contrast, the phylloquinone genes of photosynthetic parasites were coexpressed with gene family members specifically targeted to plastids (orthologs of AtCSD2 and/or Fe-SOD AtFSD2/3), mitochondria (AtGPX6) or cytosol (AtGPX8; Supplemental Data Set S2). The differential coordination between P. aegyptiaca and its photosynthetic relatives with distinct subcellular antioxidant systems is consistent with their contrasting photosynthetic capabilities, and with a prominent role of phylloquinone in PM redox homeostasis of the nonphotosynthetic holoparasite.

Discussion

An ancient origin of flexible phylloquinone biosynthesis and targeting

We present multiple lines of evidence to support a functional phylloquinone biosynthetic pathway in the nonphotosynthetic P. aegyptiaca. Our data further revealed the post-peroxisomal steps as key to flexible phylloquinone biosynthesis (Figure 5). Alternative targeting to the PM is facilitated by N-truncated MenA2 and MenG2 in conjunction with QR2. QR2 has previously been shown to function in mitigating oxidative stress in bacteria, yeast, and plants (Laskowski et al., 2002; Wrobel et al., 2002; Patridge and Ferry, 2006; Li et al., 2015). In plants, QR2s exhibit root-biased expression and are highly responsive to auxins and quinones, including HIFs in the case of parasitic plants (Matvienko et al., 2001; Laskowski et al., 2002; Ishida et al., 2017; Figure 1B). Specifically, RNAi-silencing of QR2 in Phtheirospermum japonicum significantly reduced haustorium formation (Ishida et al., 2017). The proposed QR2 involvement in PM phylloquinone biosynthesis thus represents another example of a multi-functional NAD(P)H oxidoreductase for the penultimate step, analogous to NDC1 in plastidial phylloquinone biosynthesis (Fatihi et al., 2015).

Figure 5.

Evolutionary changes in subcellular localization of phylloquinone biosynthesis. Conserved early- and mid-pathway steps are shown as circled numbers (1–7, see Figure 1) and late pathway steps MenA and MenG are abbreviated as A1/A2 and G1/G2, respectively. Circle colors denote different subcellular compartments: green, plastid; orange, peroxisome (px); purple, PM. Branches of the simplified eudicot phylogeny in the middle point to corresponding illustrations of changing pathway organization with representative species indicated. Clockwise from lower left, exclusively plastidial late steps in rosids and some asterids such as solanales; top left, dual plastidial and plasma membrane targeting in certain photosynthetic Orobanchaceae, attributable to lamiale-specific duplication of MenA and MenG. Differential losses of MenA and MenG genes in other photosynthetic, hemiparasitic (top right) and holoparasitic (lower right) lineages, with the latter exclusively PM targeting. pg, plastoglobule

PM-localized MenA2 and MenG2 likely arose from their plastidial counterparts via gene duplication in the common ancestor of Lamiales (Figure 5). Both MenA and MenG duplicates are present in Lindenbergia and Rehmannia, two nonparasitic genera sister to the parasitic Orobanchaceae (McNeal Joel et al., 2013). However, the evolutionary fate of the duplicates varied among parasitic lineages with different photosynthetic capabilities (Figure 5). The holoparasitic P. aegyptiaca, Aphyllon fasciculata, and Conopholis americana have dispensed with MenA1 and MenG1 along with the photosynthetic machinery, retaining only MenA2 and MenG2. On the other hand, the photosynthetic T. versicolor and S. hermonthica have lost MenA2 but retain the MenG1/2 duplicate, as confirmed in the recently released S. asiatica genome (Yoshida et al., 2019). In both T. versicolor and S. hermonthica, the PM-targeted MenG2 became the dominantly expressed isoform over the plastidial MenG1 (Figure 1B), which was subsequently lost in multiple holoparasites. Interestingly, in both cases, MenG2 but not MenG1 exhibited strong positive coexpression with QR2 (Figure 2, B and C). The data suggest that expression divergence of the two phylloquinone pathways in the hemiparasites predated emergence of holoparasites.

An outstanding question in PM phylloquinone biosynthesis regards the co-substrate for MenA-mediated prenylation. In photoautotrophs, the prenyl precursor of plastidial prenylquinones is phytyl-diphosphate derived from geranylgeranyl-diphosphate via de novo synthesis or from phytol released upon chlorophyll degradation (Keller et al., 1998; Ischebeck et al., 2006). In A. thaliana, the chlorophyll salvage pathway is indispensable for leaf tocopherol and phylloquinone synthesis, but seeds depend on a distinct phytol pool of as-yet-undefined origin (Valentin et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). Phelipanche and related Orobanche seeds are filled with protein and oil bodies (Joel et al., 2012), and lipids are the main storage reserve comprising up to 30% of dry seed mass (Bar-Nun and Mayer, 2002). Whether the prenyl moiety of PM phylloquinone is supplied by the cytosolic isoprenoid pathway or via other mechanisms requires further investigation.

Phylloquinone involvement in PM redox modulation

Membrane localization is a defining feature of lipid-soluble vitamin K in bacteria, animals and plants (Nowicka and Kruk, 2010). Retention and redirection of the phylloquinone pathway to PM in the nonphotosynthetic Phelipanche suggest a role analogous to the plastidial counterpart in thylakoid membranes or to menaquinone in bacterial membranes. Our data thus offer molecular support for the long-proposed involvement of phylloquinone in PM electron transport of heterotrophic tissues (Döring et al., 1998; Lüthje et al., 1998).

The P. aegyptiaca phylloquinone coexpression network comprised redox proteins typical of a transmembrane electron transport chain, consistent with a role in PM redox function. The early stages of the parasitic lifecycle can be characterized as a continuum of oxidative events, from activation and perception of host HIFs, to induction of haustoria for host penetration and vascular connection (Keyes et al., 2000; Fernández-Aparicio et al., 2016). Redox modulation is also integral to normal growth and development, as well as defense and counterdefense in the case of host–parasite interactions (Kim et al., 1998; Mittler et al., 2004). Redox-active phylloquinone in the PM may function in all of these processes, but most likely in ways specifically associated with haustorium formation based on network inference and coexpression with known parasitism genes presented herein. This interpretation is consistent with previous studies where the vitamin K antagonist dicumarol reduced haustorium development in T. versicolor (Matvienko et al., 2001; Wrobel et al., 2002).

Recently, two studies independently identified an A. thaliana PM-localized leucine-rich-repeat receptor kinase, named hydrogen peroxide-induced Ca2+ increases1 (HPCA1) or cannot respond to DMBQ1 (CARD1), as a sensor for hydrogen peroxide as well as quinones in Ca2+-dependent signal transduction (Laohavisit et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). AtCARD1 perceives various quinone molecules and has lower Km values for menadione and 1,4-naphthoquinone than DMBQ (Laohavisit et al., 2020). Its parasitic orthologs from Phtheirospermum japonicum and S. asiatica rescued A. thaliana mutants in quinone-mediated Ca2+ signaling (Laohavisit et al., 2020), suggesting a conserved quinone/ROS signaling mechanism that has been exploited for parasitism. These previously unannotated orthologs were not included in our network analysis, but of the two PaCARD transcripts we recovered, one exhibited strong coexpression with phylloquinone genes. It is tempting to speculate that phylloquinone functions as an endogenous quinone signal to bolster HIF-induced CARD signaling for haustorium formation. Phylloquinone may also facilitate disulfide bond formation between two Cys residues in the extracellular sensing domain of CARD/HPCA necessary for signal transduction (Laohavisit et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020), analogous to its function as an electron carrier for oxidative protein folding in the thylakoid lumen of photoautotrophs (Furt et al., 2010).

In closing, our work highlights a link between PM phylloquinone and parasitism that warrants future investigation. RNAi silencing of QR2 in Phtheirospermum japonicum has indeed demonstrated a negative effect on haustorium formation (Ishida et al., 2017). Recent advances in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of Phelipanche (Libiaková et al., 2018) and CRISPR genome editing should enable experimental verification of MenA2 and MenG2 function in parasitism. The existence of the alternative pathway in nonparasitic lamiales should also motivate research into the functions of PM phylloquinone in photoautotrophic species.

Materials and methods

Transcriptome assembly of parasitic plants

RNA-Seq data of Phelipanche aegyptiaca, Striga hermonthica and Triphysaria versicolor were downloaded from the Parasitic Plant Genome Project database (http://ppgp.huck.psu.edu/). After quality control filtering, cleaned reads were assembled using the custom PLAS pipeline. Briefly, PLAS performs reference-guided read mapping using Bowtie 2 v2.2.3 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) against the closely related Mimulus guttatus proteome binned by homology to facilitate parallel computing. Mapped reads were used for de novo assembly by Trinity (Haas et al., 2013), and the assembled contigs were quality-checked against the reference in each bin by Blast before being used as baits in the next round of de novo assembly. This process was repeated for up to 10 iterations until the output was stable. Assembled sequences were filtered to remove potential contaminations (e.g. host plants, protozoa, invertebrates, bacteria, fungi, and human sequences) and redundant contigs sharing ≥95% sequence identity. The transcriptome was annotated against A. thaliana and M. guttatus proteomes and UniProt database. Transcript abundance was estimated using eXpress 1.5.1 (Roberts and Pachter, 2013). Additional MenA and MenG sequences were obtained from the 1KP database (https://db.cngb.org/onekp) by BlastN against the Core Eudicots/Asterids clade using P. aegyptiaca sequences as query. The assembled transcriptome sequences of parasitic plants, the PLAS pipeline and other codes are available at https://github.com/TsailabBioinformatics/PM-PhQ. All phylloquinone and relevant transcripts described in this work were manually curated (Supplemental Data Set S1). PaMenA2 and PaMenG2 were further confirmed by RT-PCR. Briefly, cRNA derived from RNA isolated from stages 2 and 3 as described in Yang et al. (2015) was reverse transcribed using SuperScript™ IV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with mixed random hexamers and gene-specific reverse primers (Supplemental Table S2). PCR was performed using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB) with gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S2), column purified for Gibson assembly into pUC19 using NEBBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix, and confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics).

Subcellular and transmembrane domain prediction and gene structure

Phylloquinone gene sequences of photosynthetic species were downloaded from Phytozome v11. Subcellular localization was predicted by Predotar 1.04 (Small et al., 2004), TargetP 1.1 (Emanuelsson et al., 2007), Protein Prowler 1.2 (Bodén and Hawkins, 2005), and WolF PSORT (Horton et al., 2007). Transmembrane domain was predicted by TMHMM Server v.2.0 (Krogh et al., 2001), and data plotted in R. Gene structures were drawn by Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (Hu et al., 2015). The exon–intron junctions of parasitic MenA and MenG were inferred by Blast alignment of transcripts against genomic short read data of P. aegyptiaca (NCBI Sequence Read Archive accession SRX2067908), S. hermonthica (SRX2067907), and T. versicolor. Sequence alignment was performed using MUSCLE 3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004) and visualized with Color Align Conservation (www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/color_align_cons.html).

Coexpression analysis

Transcripts with an FPKM ≥2 in at least two samples were subject to pairwise Gini correlation coefficient (GCC) computation using a python script. Phylloquinone-coexpressed transcripts were defined as the 500 most highly correlated transcripts or those with a GCC ≥0.8 for each phylloquinone gene, excluding the alternative NDC1 and QR2. The union sets were subjected to GO enrichment analysis using topGO 2.26.0 (Alexa et al., 2006). To facilitate comparative analysis between species, ortholog groups were constructed by OrthoFinder 1.0.8 (Emms and Kelly, 2015). Network visualization was performed in Cytoscape 3.4.0 (Shannon et al., 2003) using prefuse force-directed layout, with a GCC cutoff of 0.6.

RNA-seq data processing of photoautotrophic species

RNA-seq data of A. thaliana, Glycine max, and Populus tremula × alba were downloaded from the NCBI SRA and quality control processed by Cutadapt 1.9.dev1 (Martin, 2011) and Trimmomatic 0.32 (Bolger et al., 2014). Reads were mapped by Tophat 2.0.13 (Kim et al., 2013), alignment sorted by Samtools 1.2 (Li et al., 2009), and read count and expression estimation obtained by HTseq 0.6.1p1 (Anders et al., 2015) and DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Arabidopsis thaliana data used for GCC computation (excluding stressed samples) were SRA236885, SRA091517, SRA269936, SRA219425, SRA308579, SRA050132, SRA067724, SRA291734, SRA269101, SRA098075, SRA100242, SRA122395, SRA163488, SRA064368, SRA246225, SRA248861, SRA202878, SRA201550, SRA303151, SRA221137, SRA272654, and SRA221060. G. max data included SRA187830, SRA047293, SRA036577, SRA116533, SRA091756, SRA187830, SRA036538, SRA036577, and SRA129337. P. tremula × alba datasets were SRA274261 and SRA097208.

Phylogenetic tree construction

The protein sequences of Phelipanche ramosa PrPRX1 (AAY89058) and PrPOX1 (AAU04440), and Striga asiatica SaPOXA (AAB97853) and SaPOXB (AF043235) were searched against the PLAS assemblies of P. aegyptiaca, S. hermonthica, and T. versicolor to identify orthologs. Their protein sequences were aligned by MUSCLE 3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004) and the alignment trimmed by Gblocks (Castresana, 2000). Bayesian phylogenetic tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 (Ronquist et al., 2012). Phylogenetic trees for MenA and MenG were similarly constructed using protein sequences obtained from Phytozome or 1KP followed by manual curation (Supplemental Data Set S1), and visualized by MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018).

Phylloquinone analysis

Phelipanche aegyptiaca seeds were surface-sterilized, pre-conditioned on moist filter paper for 7–10 d, and treated with GR-24 for 4–6 d before collection of stage 1 germinated seeds as described (Westwood et al., 2012). Three biological replicates from independent germination experiments were used for the analysis. Nonimbibed A. thaliana (Col-0) seeds from three independent collections were used without further treatment. Tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, freeze-dried, and milled to a fine powder for phylloquinone analysis as described (Booth et al., 1994). Tissues were partitioned twice in isopropanol:hexane (3:2 v/v), with menaquinone MK-4 (Sigma V9378) as a reference for P. aegyptiaca analysis. The hexane phase was dried under nitrogen, and resuspended in methylene chloride:methanol (1:4, v/v), 10 mM ZnCl2, 5 mM Na-acetate, and 5 mM acetic acid. Isocratic reverse-phase HPLC (Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column, 5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm) was carried out using methanol:methylene chloride (9:1, v/v), with post-column Zn reduction and fluorescence detection (excitation 244 nm, emission 418 nm). Phylloquinone peaks were verified by comparison with the authentic standard (Sigma 47773) and concentrations were estimated using calibration curves of the standard.

Nicotiana benthamiana transformation and confocal microscopy

PaMenA2 and PaMenG2 coding sequences were gene-synthesized (General Biosystems) and Gibson-assembled with PCR-amplified GFP (from pCXDG) into BamHI-digested pCXSN vector (Chen et al., 2009; see Supplemental Table S2 for primers). Due to concern over 35S promoter silencing in co-transformation experiments, another PaMenA2-GFP construct was prepared by PCR using pCX-PaManA2-GFP as template and primers containing a viral 2A peptide bridge sequence (Luke et al., 2015) to link the hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT)-coding sequence to PaMenA2-GFP behind double 35S promoter as one transcriptional unit (35S:PaMenA2-GFP-2A-HPT; Supplemental Table S2). All constructs were sequence verified. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana was performed as described and regenerated on selection media (Pathi et al., 2013) using individual constructs (pCX-PaMenA2-GFP and pCX-PaMenG2-GFP) or in conjunction with a PM (AtPIP2A-mCherry) marker (Nelson et al., 2007; pCX-PaMenA2-GFP-2A-HPT + AtPIP2A-mCherry and pCX-PaMenG2-GFP + AtPIP2A-mCherry). Root samples from independent transformants were screened under a fluorescence microscope and at least three positive lines were further examined using a Zeiss LSM 880 upright confocal microscope in the Biomedical Microscopy Core at the University of Georgia. GFP signal was detected using an Argon excitation laser (488 nm) and an emission filter at 490–540 nm, and mCherry signal was obtained using a HeNe excitation laser (543 nm) and an emission filter at 547–697 nm.

Escherichia coli complementation

The PaMenG2 and EcMenG (positive control) coding sequences were PCR-amplified (see Supplemental Table S2 for primers) for Gibson assembly into a constitutive expression vector pUCM (Kim et al., 2010), and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Sequence-verified plasmids were transformed into E. coli strain JW5581 carrying the mutated menG (ubiE) gene (obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center). At least two PCR-confirmed colonies per construct were used for complementation experiments. Approximately 30 mg of freeze-dried bacterial cells were extracted as described (Booth et al., 1994) using a Misonix sonicator. Reverse-phase HPLC conditions were the same as above except with a run time of 40 min.

Accession numbers

The accession numbers of genes mentioned in this work are provided in Supplemental Table S3. Additional sequences from PLAS or 1KP are provided in Supplemental Data Set S1.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 MenE sequence alignment with C-terminal peroxisome targeting signal PTS1.

Supplemental Figure S2 . MenB sequence alignment with N-terminal peroxisome targeting signal PTS2.

Supplemental Figure S3 . DHNAT sequence alignment with C-terminal peroxisome targeting signal PTS1.

Supplemental Figure S4 . MenA sequence alignment.

Supplemental Figure S5 . MenG sequence alignment.

Supplemental Figure S6 . QR2 sequence alignment.

Supplemental Figure S7 . The signal intensity profiles of plasma membrane marker AtPIP2A with PaMenA2 or PaMenG2.

Supplemental Table S1 . Plastid-targeting prediction for ICS, PHYLLO and NDC1.

Supplemental Table S2 . List of primers.

Supplemental Table S3 . Accession numbers.

Supplemental Data Set S1 . PLAS-assembled or 1KP-derived and manually curated transcript sequences of phylloquinone biosynthetic and coexpressed genes described in the manuscript.

Supplemental Data Set S2 . Lists of transcripts used in coexpression network analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L.-J. Xue for the GCC Python script, M. Curley, M. Tsai, N. Rodman, and K.B. Aulakh for laboratory assistance, M.K. Kandasamy for confocal microscopy assistance, and D. Lynn (Emory University) for insightful discussion. This research was supported by Georgia Research Alliance-Hank Haynes Forest Biotechnology Endowment (C.-J.T.), National Science Foundation grants IOS-1444567, IOS-1546867 (C.-J.T.), and IOS-1238057 (J.H.W.), National Institute of Food and Agriculture grant VA-135997 (J.H.W.), and University of Georgia Graduate School’s Innovative and Interdisciplinary Research Grant (X.G.).

C.-J.T. and X.G. conceived the study; X.G. performed all bioinformatic analyses with contributions from C.-J.T.; I.-G.C. performed bacterial complementation, plant transformation and microscopic analyses with help from M.A.O.; S.A.H., B.N., and I.-G.C. performed metabolic analyses; K.C. and J.H.W. contributed materials; X.G. and C.-J.T. wrote the manuscript with input from S.A.H. and J.H.W.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Chung-Jui Tsai (cjtsai@uga.edu).

References

- Alexa A, Rahnenführer J, Lengauer T (2006) Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics 22:1600–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31:166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attacha S, Solbach D, Bela K, Moseler A, Wagner S, Schwarzländer M, Aller I, Müller Stefanie J, Meyer Andreas J (2017) Glutathione peroxidase‐like enzymes cover five distinct cell compartments and membrane surfaces in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ 40:1281–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2: 2006.0008-2006.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babujee L, Wurtz V, Ma C, Lueder F, Soni P, van Dorsselaer A, Reumann S (2010) The proteome map of spinach leaf peroxisomes indicates partial compartmentalization of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) biosynthesis in plant peroxisomes. J Exp Bot 61:1441–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandaranayake PCG, Filappova T, Tomilov A, Tomilova NB, Jamison-McClung D, Ngo Q, Inoue K, Yoder JI (2010) A single-electron reducing quinone oxidoreductase is necessary to induce haustorium development in the root parasitic plant Triphysaria. Plant Cell 22:1404–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Nun N, Mayer AM (2002) Composition of and changes in storage compounds in Orobanche aegyptiaca seeds during preconditioning. Israel J Plant Sci 50:278–279 [Google Scholar]

- Barr R, Pan RS, Crane FL, Brightman AO, Morré DJ (1992) Destruction of vitamin K1 of cultured carrot cells by ultraviolet radiation and its effect on plasma membrane electron transport reactions. Biochem Int 27:449–456 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérczi A, Møller IM (2000) Redox enzymes in the plant plasma membrane and their possible roles. Plant Cell Environ 23:1287–1302 [Google Scholar]

- Bernal M, Casero D, Singh V, Wilson GT, Grande A, Yang H, Dodani SC, Pellegrini M, Huijser P, Connolly EL. , et al. (2012) Transcriptome sequencing identifies SPL7-regulated copper acquisition genes FRO4/FRO5 and the copper dependence of iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24:738–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodén M, Hawkins J (2005) Prediction of subcellular localization using sequence-biased recurrent networks. Bioinformatics 21:2279–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth SL, Davidson KW, Sadowski JA (1994) Evaluation of an HPLC method for the determination of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in various food matrixes. J Agric Food Chem 42:295–300 [Google Scholar]

- Brettel K, Sétif P, Mathis P (1986) Flash-induced absorption changes in photosystem I at low temperature: evidence that the electron acceptor A1 is vitamin K1. FEBS Lett 203:220–224 [Google Scholar]

- Carrie C, Murcha MW, Kuehn K, Duncan O, Barthet M, Smith PM, Eubel H, Meyer E, Day DA, Millar AH. , et al. (2008) Type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are targeted to mitochondria and chloroplasts or peroxisomes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett 582:3073–3079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassin-Ross G, Hu J (2014) Systematic phenotypic screen of Arabidopsis peroxisomal mutants identifies proteins involved in β-oxidation. Plant Physiol 166:1546–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17:540–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Songkumarn P, Liu J, Wang G-L (2009) A versatile zero background T-vector system for gene cloning and functional genomics. Plant Physiol 150:1111–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F-y, Blackburn K, Lin Y-m, Goshe MB, Williamson JD (2009) Absolute protein quantification by LC/MSE for global analysis of salicylic acid-induced plant protein secretion responses. J Proteome Res 8:82–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring O, Lüthje S, Böttger M (1992a) Inhibitors of the plasma membrane redox system of Zea mays L. roots. The vitamin K antagonists dicumarol and warfarin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1110:235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring O, Lüthje S, Böttger M (1992b) Modification of the activity of the plasma membrane redox system of Zea mays L. roots by vitamin K3 and dicumarol. J Exp Bot 43:175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döring O, Lüthje S, Böttger M (1998) To be or not to be — a question of plasma membrane redox? InBehnke HD, Esser K, Kadereit JW, Lüttge U, Runge M, eds, Progress in Botany: Genetics Cell Biology and Physiology Ecology and Vegetation Science. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 328–354 [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H (2007) Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protocols 2:953–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms DM, Kelly S (2015) OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol 16:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugeni Piller L, Abraham M, Dörmann P, Kessler F, Besagni C (2012) Plastid lipid droplets at the crossroads of prenylquinone metabolism. J Exp Bot 63:1609–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugeni Piller L, Besagni C, Ksas B, Rumeau D, Bréhélin C, Glauser G, Kessler F, Havaux M (2011) Chloroplast lipid droplet type II NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase is essential for prenylquinone metabolism and vitamin K1 accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:14354–14359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatihi A, Latimer S,, Schmollinger S, Block A, Dussault PH, Vermaas WFJ, Merchant SS, Basset GJ (2015) A dedicated type II NADPH dehydrogenase performs the penultimate step in the biosynthesis of vitamin K1 in Synechocystis and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27:1730–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aparicio M, Masi M, Maddau L, Cimmino A, Evidente M, Rubiales D, Evidente A (2016) Induction of haustorium development by sphaeropsidones in radicles of the parasitic weeds Striga and Orobanche. A structure–activity relationship study. J Agric Food Chem 64:5188–5196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furt F, Oostende Cv, Widhalm JR, Dale MA, Wertz J, Basset GJC (2010) A bimodular oxidoreductase mediates the specific reduction of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in chloroplasts. Plant J 64:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcion C, Lohmann A, Lamodiere E, Catinot J, Buchala A, Doermann P, Metraux J-P (2008) Characterization and biological function of the ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 147:1279–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles JB, Scott L, Abdelhak F, Eric S, Anna B (2016) Phylloquinone (Vitamin K1): occurrence, biosynthesis and functions. Mini-Rev Med Chem 16:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Verdejo CI, Barandiaran X, Moreno MT, Cubero JI, Di Pietro A (2006) A peroxidase gene expressed during early developmental stages of the parasitic plant Orobanche ramosa. J Exp Bot 57:185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M,, Blood PD, Bowden J, Couger MB, Eccles D, Li B, Lieber M. , et al. (2013) De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-Seq: reference generation and analysis with Trinity. Nature Protocols 8: 10.1038/nprot.2013.1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Park K-J, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K (2007) WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W585–W587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Jin J, Guo A-Y, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G (2015) GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31:1296–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischebeck T, Zbierzak AM, Kanwischer M, Dörmann P (2006) A salvage pathway for phytol metabolism in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 281:2470–2477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida JK, Wakatake T, Yoshida S, Takebayashi Y, Kasahara H, Wafula E, dePamphilis CW, Namba S, Shirasu K (2016) Local auxin biosynthesis mediated by a YUCCA flavin monooxygenase regulates haustorium development in the parasitic plant Phtheirospermum japonicum. Plant Cell 28:1795–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida JK, Yoshida S, Shirasu K (2017) Quinone oxidoreductase 2 is involved in haustorium development of the parasitic plant Phtheirospermum japonicum. Plant Signal Behav 12:e1319029–e1319029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Wilson G, Connolly E (2014) The diverse roles of FRO family metalloreductases in iron and copper homeostasis. Front Plant Sci 5: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel DM, Bar H, Mayer AM, Plakhine D, Ziadne H, Westwood JH, Welbaum GE (2012) Seed ultrastructure and water absorption pathway of the root-parasitic plant Phelipanche aegyptiaca (Orobanchaceae). Ann Bot 109:181–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiping S, Soll J, Schultz G (1984) Site of methylation of 2-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinol in phylloquinone (vitamin K1) synthesis in spinach chloroplasts. Phytochemistry 23:89–91 [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Morishima K, Tanabe M (2018) New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D590–D595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamoko M, Cline S, Redding K, Ruiz N, Hamel PP (2011) Lumen thiol oxidoreductase1, a disulfide bond-forming catalyst, is required for the assembly of photosystem II in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23:4462–4475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller Y, Bouvier F, d'Harlingue A, Camara B (1998) Metabolic compartmentation of plastid prenyllipid biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem 251:413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes JW, O'Malley CR, Kim D, Lynn GD (2000) Signaling organogenesis in parasitic angiosperms: Xenognosin generation, perception, and response. J Plant Growth Regul 19:217–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kocz R, Boone L, John Keyes W, Lynn DG (1998) On becoming a parasite: evaluating the role of wall oxidases in parasitic plant development. Chem Biol 5:103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL (2013) TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol 14:R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Park YH, Schmidt-Dannert C, Lee PC (2010) Redesign, reconstruction, and directed extension of the Brevibacterium linens C40 carotenoid pathway in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5199–5206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: application to complete genomes1. J Mol Biol 305:567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K (2018) MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 35:1547–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laohavisit A, Wakatake T, Ishihama N, Mulvey H, Takizawa K, Suzuki T, Shirasu K (2020) Quinone perception in plants via leucine-rich-repeat receptor-like kinases. Nature [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski MJ, Dreher KA, Gehring MA, Abel S, Gensler AL, Sussex IM (2002) FQR1, a novel primary auxin-response gene, encodes a flavin mononucleotide-binding quinone reductase. Plant Physiol 128:578–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PT, Hsu AY, Ha HT, Clarke CF (1997) A C-methyltransferase involved in both ubiquinone and menaquinone biosynthesis: isolation and identification of the Escherichia coli ubiE gene. J Bacteriol 179:1748–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leebens-Mack JH, Barker MS, Carpenter EJ, Deyholos MK, Gitzendanner MA,, Graham SW, Grosse I, Li Z, Melkonian M, Mirarab S. , et al. (2019) One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature 574:679–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing S (2009) The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Naseem S, Sharma S, Konopka JB (2015) Flavodoxin-like proteins protect Candida albicans from oxidative stress and promote virulence. PLoS Pathogens 11:e1005147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Liu Y, Jariwala J, Lynn DG, Palmer AG (2016) Detection and adaptation in parasitic angiosperm host selection. Am J Plant Sci 7:1275–1290 [Google Scholar]

- Libiaková D, Ruyter-Spira C, Bouwmeester HJ, Matusova R (2018) Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformed calli of the holoparasitic plant Phelipanche ramosa maintain parasitic competence. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 135:321–329 [Google Scholar]

- Lochner K, Döring O, Böttger M (2003) Phylloquinone, what can we learn from plants? BioFactors 18:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann A, Schottler MA, Brehelin C, Kessler F, Bock R, Cahoon EB, Dormann P (2006) Deficiency in phylloquinone (vitamin K1) methylation affects prenyl quinone distribution, photosystem I abundance and anthocyanin accumulation in the arabidopsis AtmenG mutant. J Biol Chem 281:40461–40472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Wang H-R, Li H, Cui H-R, Feng Y-G, Wang X-Y (2013) A chloroplast membrane protein LTO1/AtVKOR involving in redox regulation and ROS homeostasis. Plant Cell Rep 32:1427–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke GA, Roulston C, Tilsner J, Ryan MD (2015) Growing uses of 2A in plant biotechnology. In D Ekinci, ed, Biotechnology. InTech, Rijek, pp 165–193

- Lüthje S, Döringe O, Böttger M (1992) The effects of vitamin K3 and dicumarol on the plasma membrane redox system and h+ pumping activity of Zea mays L roots measured over a long time scale. J Exp Bot 43:183–188 [Google Scholar]

- Lüthje S, Van Gestelen P, Córdoba-Pedregosa MC, González-Reyes JA, Asard H, Villalba JM, Böttger M (1998) Quinones in plant plasma membranes — a missing link? Protoplasma 205:43–51 [Google Scholar]

- Margis R, Dunand C, Teixeira Felipe K, Margis‐Pinheiro M (2008) Glutathione peroxidase family – an evolutionary overview. FEBS J 275:3959–3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmagne A, Rouet M-A, Ferro M, Rolland N, Alcon C, Joyard J, Garin J, Barbier-Brygoo H, Ephritikhine G (2004) Identification of new intrinsic proteins in Arabidopsis plasma membrane proteome. Mol Cell Proteom 3:675–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M (2011) Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J 17:10–12 [Google Scholar]

- Matvienko M, Wojtowicz A, Wrobel R, Jamison D, Goldwasser Y, Yoder JI (2001) Quinone oxidoreductase message levels are differentially regulated in parasitic and non-parasitic plants exposed to allelopathic quinones. Plant J 25:375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal Joel R, Bennett Jonathan R, Wolfe Andrea D, Mathews S (2013) Phylogeny and origins of holoparasitism in Orobanchaceae. Am J Bot 100:971–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalecka AM, Svensson ÅS, Johansson FI, Agius SC, Johanson U, Brennicke A, Binder S, Rasmusson AG (2003) Arabidopsis genes encoding mitochondrial type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases have different evolutionary origin and show distinct responses to light. Plant Physiol 133:642–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Gollery M, Van Breusegem F (2004) Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci 9:490–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natera SHA, Ford KL, Cassin AM, Patterson JH, Newbigin EJ, Bacic A (2008) Analysis of the Oryza sativa plasma membrane proteome using combined protein and peptide fractionation approaches in conjunction with mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 7:1159–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51:1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka B, Kruk J (2010) Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797:1587–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostende Cv, Widhalm JR, Basset GJC (2008) Detection and quantification of vitamin K1 quinol in leaf tissues. Phytochemistry 69:2457–2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathi KM, Tula S, Tuteja N (2013) High frequency regeneration via direct somatic embryogenesis and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of tobacco. Plant Signal Behav 8:e24354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patridge EV, Ferry JG (2006) WrbA from Escherichia coli and Archaeoglobus fulgidus is an NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase. J Bacteriol 188:3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechanova O, Hsu C-Y, Adams JP, Pechan T, Vandervelde L, Drnevich J, Jawdy S, Adeli A, Suttle JC, Lawrence AM. , et al. (2010) Apoplast proteome reveals that extracellular matrix contributes to multistress response in poplar. BMC Genom 11:674–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Pachter L (2013) Streaming fragment assignment for real-time analysis of sequencing experiments. Nat Methods 10:71–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP (2012) MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61:539–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer P, Heyno E, Drepper F, Krieger-Liszkay A (2008) Naphthoquinone-dependent generation of superoxide radicals by quinone reductase isolated from the plasma membrane of soybean. Plant Physiol 147:864–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz G, Soll J, Ellerbrock BH (1981) Site of prenylation reaction in synthesis of phylloquinone (vitamin K1) by spinach chloroplasts. Eur J Biochem 117:329–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N,, Schwikowski B, Ideker T (2003) Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13:2498–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small I, Peeters N, Legeai F, Lurin C (2004) Predotar: A tool for rapidly screening proteomes for N-terminal targeting sequences. Proteomics 4:1581–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin HE, Lincoln K, Moshiri F, Jensen PK, Qi Q, Venkatesh TV, Karunanandaa B, Baszis SR, Norris SR, Savidge B. , et al. (2006) The Arabidopsis vitamin E pathway gene5-1 mutant reveals a critical role for phytol kinase in seed tocopherol biosynthesis. Plant Cell 18:212–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi C, Bonnin E, Calvez S, Thalouarn P, Simier P (2007) Activity of secreted cell wall-modifying enzymes and expression of peroxidase-encoding gene following germination of Orobanche ramosa. Biologia Plantarum 51:391–394 [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li Q, Zhang A, Zhou W, Jiang R, Yang Z, Yang H, Qin X, Ding S, Lu Q. , et al. (2017) The phytol phosphorylation pathway is essential for the biosynthesis of phylloquinone, which is required for photosystem i stability in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 10:183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood JH, dePamphilis CW, Das M, Fernández-Aparicio M, Honaas LA, Timko MP, Wafula EK, Wickett NJ, Yoder JI (2012) The Parasitic Plant Genome Project: new tools for understanding the biology of Orobanche and Striga. Weed Sci 60:295–306 [Google Scholar]

- Westwood JH, Yoder JI, Timko MP, dePamphilis CW (2010) The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci 15:227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel RL, Matvienko M, Yoder JI (2002) Heterologous expression and biochemical characterization of an NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase from the hemiparasitic plant Triphysaria versicolor. Plant Physiol Biochem 40:265–272 [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Chi Y, Jiang Z, Xu Y, Xie L, Huang F, Wan D, Ni J, Yuan F, Wu X. , et al. (2020) Hydrogen peroxide sensor HPCA1 is an LRR receptor kinase in Arabidopsis. Nature 578:577–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wafula EK, Honaas LA, Zhang H, Das M, Fernandez-Aparicio M, Huang K, Bandaranayake PCG, Wu B, Der JP. , et al. (2015) Comparative transcriptome analyses reveal core parasitism genes and suggest gene duplication and repurposing as sources of structural novelty. Mol Biol Evol 32:767–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida S, Kim S, Wafula EK, Tanskanen J,, Kim Y-M, Honaas L, Yang Z, Spallek T, Conn CE, Ichihashi Y. , et al. (2019) Genome sequence of Striga asiatica provides insight into the evolution of plant parasitism. Curr Biol 29:3041–3052.e3044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Liu T, Ren G, Hörtensteiner S, Zhou Y, Cahoon EB, Zhang C (2014) Chlorophyll degradation: the tocopherol biosynthesis-related phytol hydrolase in Arabidopsis seeds is still missing. Plant Physiol 166:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.