Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) type I signal peptidases (ER SPases I) are vital proteases that cleave signal peptides from secreted proteins. However, the specific function of ER SPase I in plants has not been genetically characterized, and the substrate is largely unknown. Here, we report the identification of a maize (Zea mays) miniature seed6 (mn6) mutant. The loss-of-function mn6 mutant exhibited severely reduced endosperm size. Map-based cloning and molecular characterization indicated that Mn6 is an S26-family ER SPase I, with Gly102 (box E) in Mn6 critical for protein function during processing. Mass spectrometric and immunoprecipitation analyses revealed that Mn6 is predominantly involved in processing carbohydrate synthesis-related proteins, including the cell wall invertase miniature seed1 (Mn1), which is specifically expressed in the basal endosperm transfer layer. RNA and protein expression levels of Mn1 were both significantly downregulated in the mn6 mutant. Due to the significant reduction in cell wall invertase activity in the transfer cell layer, mutation of Mn6 caused dramatic defects in endosperm development. These results suggest that proper maturation of Mn1 by Mn6 may be a crucial step for proper seed filling and maize development.

Miniature seed6 (Mn6), involved in maize (Zea mays) seed development, is necessary for processing the cell wall invertase Mn1, which is specifically expressed in the basal endosperm transfer layer.

Introduction

Endosperm development is important for the biosynthesis and storage of starch and proteins in maize (Zea mays) seeds and is of great economic importance because of its role in feed, food, and biofuel production. Gene expression is closely associated with the physiological process of endosperm development. Studies on the molecular mechanism of maize endosperm development are crucial for the genetic improvement of kernel-related traits.

Maize has a long history of genetic exploration, during which a wealth of mutant resources has been developed. Two predominant types of small-seeded mutants are known in maize. One type is defective kernel mutants, which show defective development of the endosperm and embryo (Neuffer and Sheridan, 1980). The other type is miniature seed (Mn) mutants, which are marked by a drastic reduction in endosperm weight and size relative to that of the wild-type, but with little or no effect on embryo development and on subsequent vegetative and reproductive growth. Five Mn maize mutants have been reported, designated Mn1–5 (Lowe and Nelson Jr, 1946; Stinard, 1991; Cheng et al., 1996). To date, only the mn1 mutant has been intensively studied (Miller and Chourey, 1992; Cheng et al., 1996; Carlson et al., 2000; LeClere et al., 2008). The mn2–5 mutants have been subject to phenotypic characterization but no mutated gene has been cloned. Mn1, which encodes an important endosperm-specific cell wall invertase isoform, Incw2, is associated with seed filling via digestion of sucrose into fructose and glucose in the basal endosperm transfer layer (BETL) of the endosperm (Miller and Chourey, 1992; Cheng et al., 1996). The mn1 mutant is a typical Mn mutant and provided the earliest genetic demonstration of the role of cell wall invertase in seed filling. Mn1 is especially expressed in the BETL and is critical for the majority of metabolic and signaling pathways associated with hexose sugars during endosperm development (Cheng et al., 1996; Wobus and Weber, 1999; LeClere et al., 2008, 2010). However, the mn1 mutation is nonlethal, probably because of the low activity of cell wall invertase encoded by a second gene, Incw1 (Chourey et al., 2006).

Over the years, several pleiotropic changes caused by the Mn1 single-gene mutation have been reported. As first described by Lowe and Nelson (1946), homozygous recessive mn1 mutants are seed-specific, bearing seeds one-fifth of the normal (Mn1) seed weight at maturity (Lowe and Nelson Jr, 1946). Cheng et al. (1996) noted that the mn1 mutant showed the separation of the pedicel from the developing endosperm and physical destruction of cells, leading to formation of a gap between the pedicel and endosperm. Vilhar et al.(2002) observed that cell number and cell size were reduced during endosperm development in the mn1 mutant. Interestingly, subsequent studies indicate that the mn1 mutant is deficient in indoleacetic acid, which is suggestive of the presence of sugar–auxin crosstalk (LeClere et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009; Chourey et al., 2010; Doll et al., 2017). This evidence suggests that Mn1 plays an important role as a gateway for the entry of sugars and other nutrients from maternal cells into the filial tissues. Li et al. (2013) showed that the constitutive expression of Mn1 in maize may improve grain filling and thereby substantially improve grain yield. Although many important advances in characterizing the functions of Mn1 have been achieved in recent years, few data on the genetic regulation or modification of Mn1 have been reported. With an increasing number of studies focused on the roles of Mn1 in seed filling and development, the elucidation of the regulatory mechanisms of Mn1 at the transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels is required.

Protein processing after translation, a vital post-translational modification, is a crucial step in the formation of a mature protein of normal function ( Paetzel et al., 2002; Auclair et al., 2012; Midorikawa et al., 2014; Oue et al., 2014; Dalbey et al., 2017). In eukaryotes, the type I signal peptidases (SPase I) family is complex, which includes ER SPases I, mitochondrial SPases I, and chloroplastic SPases I (Paetzel et al., 2002; Tuteja, 2005; Shipman-Roston et al., 2010; Midorikawa et al., 2014). All SPase I proteins contain five conserved regions (boxes A−E); however, the whole sequence similarity of SPase I is a little low (Dalbey et al., 1997; Paetzel et al., 2002). The functions of the conserved regions among SPases I may be similar. Box A includes single or multiple transmembrane segments, which anchor the catalytic region in the membrane (Klug et al., 1997; Bairl and Muller, 1998; Paetzel et al., 2000; Rahman et al., 2003). Boxes B−E participate in catalytic activity (Paetzel et al., 2000).

The ER SPase I cleaves ER signal peptides after release of proteins into the ER lumen. The ER signal peptides could be divided into an N-terminal region containing at least one basic residue, a hydrophobic core of 12–20 residues, and a C-terminal polar domain usually ending with the Ala–X–Ala motif (Paetzel et al., 2002). Unlike the mitochondrial and chloroplastic SPases, which use the same Ser–Lys dyad mechanism, the ER SPases use a different catalytic mechanism that involves Ser and His residues (Chen et al., 1999; VanValkenburgh et al., 1999). Disruption of the ER SPases I catalytic subunit leads to cell death in yeast (Böhni et al., 1988), Plasmodium falciparum (Tuteja et al., 2008), and Leishmania manilensis (Taheri et al., 2010). The ER SPases I subunit (LmSPC1) is essential for survival of Locusta migratoria manilensis and affects molting, feeding and reproduction development (Zhang and Xia, 2014). Although all ER SPases I cleave signal peptides from proteins, the effects of ER SPase I genes on physiological functions of angiosperms and animals may be different. Angiosperms and animals include many types of cells that perform specific functions. The functions of ER SPases I in animals have been described in the model insect Drosophila and human (Homo sapiens) gastric cancer cells. In Drosophila, the subunit SPase12 was disrupted, but essential catalytic subunits were not identified (Haase et al., 2013); in gastric cancer cells, Secretory protein 11 (SEC11A) contributes to malignant progression through the promotion of transforming growth factor (TGF)-αsecretion (Oue et al., 2014). To date, the specific function of ER SPase I has not been genetically characterized in any plant species, with the substrate selectivity being largely unknown.

In this study, we cloned and genetically characterized Mn6, which is involved in seed filling and development in maize. Map-based cloning revealed that a point mutation in Mn6 was responsible for the mutant phenotype, which was verified by transgenic complementation of mn6 and an allelism test between two types of mn6 allelic mutants. Mn6 encodes a putative ER SPase I protein. Functional analysis indicated that Mn6 is involved in kernel development directly through post-translational modification of Mn1. The present findings place Mn6 and Mn1 in the same pathway for sugar cleavage and subsequent seed filling.

Results

Phenotypic and genetic characterization of mn6

The mn6 mutant was isolated from a mutant library in the “B73” background constructed in our laboratory following ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis. The mn6 mutation behaved as a single recessive trait because self-pollinated mn6 heterozygotes showed segregation of normal and miniature kernels conforming to a 1:3 ratio (Figure 1A). Macroscopically, mature seeds of the mn6 mutant were relatively small compared with those of wild-type (WT) siblings. In addition, the mn6 mutant showed alterations in the peripheral portion of endosperm, which included a proportionally larger vitreous region. Although the mn6 embryo is smaller than that of the wild-type, the seeds of mn6 germinated readily and no phenotypic differences were observed at the vegetative stages in both greenhouse and field conditions (Figure 1, B and C;Supplemental Figure S1). However, the size and weight of the kernel showed drastic reduction in the mn6 mutant (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Phenotypic analysis of the maize mn6 mutant. (A) Mature ear of a self-pollinated heterozygous plant (Mn6) showing segregation of WT and miniature kernels. The black arrow indicates a miniature kernel. Bar = 1 cm. (B) Face view of WT and mn6-1 mutant kernels. Bar = 1 cm. Face view (C) and back view (D) of WT and mn6-1 mutant kernels. Transverse (E) and longitudinal (F) sections of WT and mn6-1 kernels from the same F2 segregated ear. The WT in this experiment was “B73”. Bar = 0.5 cm.

The kernels of the mn6 mutant also exhibited delayed development compared with that of the wild-type. Cytological sections of the mn6 mutant seed at 12 d after pollination (DAP) revealed that endosperm development was affected, resulting in a detectable gap between the endosperm (Figure 2A) and pedicel, and this gap disappeared at 20 DAP (Figure 2B). In contrast, the embryo of the wild-type at 12 DAP already showed the differentiation of the scutellum, two leaf primordia, root apical meristem, and visible vascular tissue, and the endosperm was much larger than that of the mn6 mutant kernel (Figure 2B). Electron microscopic observation further indicated that the degradation rate of seed coat in mn6 was significantly lower than that of the wild-type (Figure 2C). Compared with the wild-type, the mn6 mutant showed alterations in the peripheral region of the endosperm. In the normally soft inner region of the endosperm, the number of starch granules accumulate less in the mn6 mutant compare to the WT (Figure 2D). We also analyzed the accumulation zein proteins between mn6 and WT. The result showed that there was no distinct change in the zein proteins compared to the wild-type (Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Cytological analysis of the maize mn6 mutant. (A, B) Cytological section of mn6 mutant and WT seeds at 12 DAP (A) and 20 DAP (B). Bar = 1 mm. The red arrows indicate a detectable gap between the endosperm and pedicel. (C) Scanning electron micrographs of the seed coat in developing kernels of the mn6 mutant and WT at 20 DAP. The left and right two-way arrows are of identical length. (D) Scanning electron micrographs of the peripheral regions of mature endosperm of the mn6 mutant and WT. The WT in this experiment was “B73”. The mn6 mutant in this experiment was mn6-2.

Map-based cloning of mn6

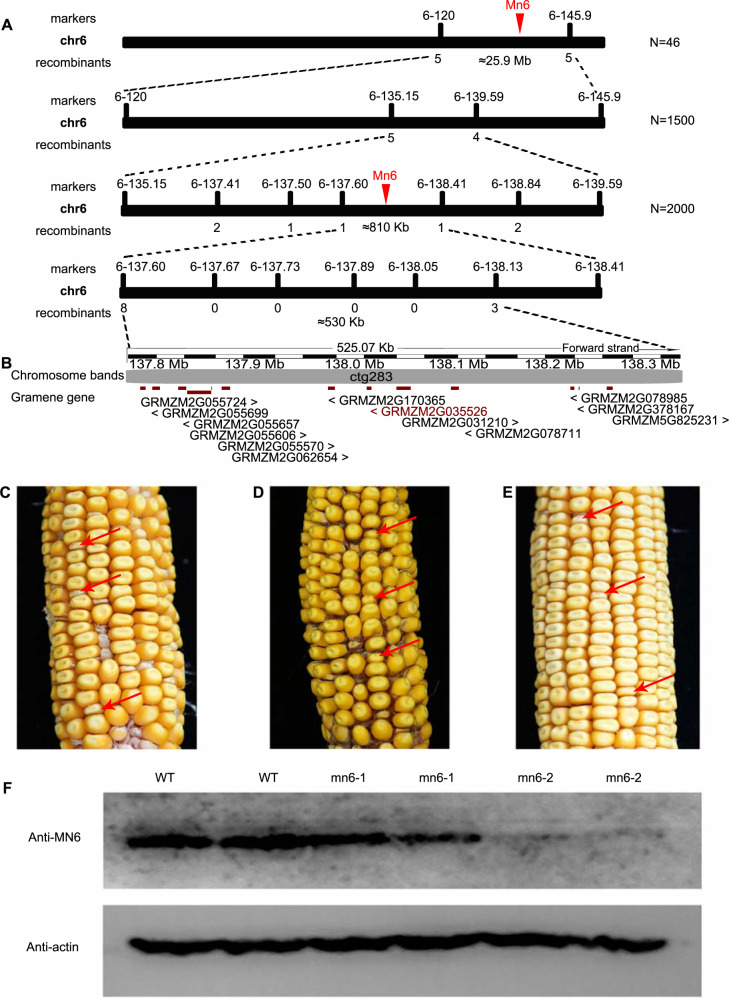

We adopted a map-based cloning approach to isolate the Mn6 gene. The mapping population was the F2 generation from a cross between the heterozygous mn6 mutant and the maize inbred line “Mo17”. The mn6 locus was initially mapped to the genomic region between the simple sequence repeat markers 6-120 and 6-145.9 in B73 reference genome (Version 2). By screening a mapping population of almost 1,500 individual F2 lines, mn6 was narrowed to a smaller genomic region flanked by the markers 6-137.60 and 6-138.41. A further 2,000 individual F2 lines and additional markers were used for fine mapping, resulting in localization of mn6 to a ∼530-kb interval between markers 6-137.60 and 6-138.13 (Figure 3A). Gene annotations within this ∼530-kb region in the maize B73 reference genome (Version 2) consisted of 13 predicted genes. These 13 genes were amplified from the mn6 mutant and the assembled sequences were mapped to the B73 reference genome. In gene GRMZM2G035526 (a putative Type I Signal Peptidase homolog), a G/A transversion at nucleotide 2041 (numbering in accordance with GRMZM2G035526_P01) leading to an amino acid change from Gly to Ser was detected (Supplemental Figure S4, A and B). Alignment of additional sequences indicated that the Gly residue at this site is conserved among maize, rice, Arabidopsis, humans, and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Supplemental Figure S4C).

Figure 3.

Map-based cloning and validation of Mn6. (A, B) The Mn6 locus was mapped to a 530-kb region on chromosome 6 (A) with 13 candidate genes (B). Red arrow heads in (A) indicate mutation site. Red font in (B) indicate mutation gene. (C) Mature ear of self-pollinated heterozygous plant (Mn6-2) showing segregation of WT and miniature kernels. (D) Allele tests were performed between mn6-1/+ and mn6-2/+. Pollen of mn6-1/+ was donated to mn6-2/+. The (mn6-1/+ × mn6-2/+) heterozygotes showed a 1:3 segregation ratio of miniature:normal kernels. (E) Ear of self-pollinated double heterozygous (+/mn6-2; transgene Mn6/-) plant showing the frequency of miniature kernels was (6.54% ± 1.13%) close to the 1:16 ratio predicted in the case of complementation. Red arrows in (C, D) and (E) indicate miniature kernels. (F) Immunoblot comparing accumulation of Mn6 in WT, mn6-1, and mn6-2 kernels at 8 DAP. Anti-actin was used as a sample loading control. The WT in this experiment was “B73”.

To confirm that the candidate gene GRMZM2G035526 corresponds to Mn6, we used a functional complementation test by genetic transformation of the WT allele in the mn6 background. Segregating ears of self-pollinated double heterozygotes (+/mn6, −/Mn6-myc) plants showed that the frequency of miniature kernels (6.54% ± 1.13%) relative to normal kernels was much closer to the 1:16 ratio (Figure 3C). Phenotyping (Figure 3C) and genotyping analysis (Supplemental Figure S5, A–E) showed the transgenic seeds carrying transformed WT GRMZM2G035526 sequence functionally complemented the loss-of-function of mn6 and rescued the mutant phenotype.

An allelism test was performed between two types of mn6 allelic mutants to confirm the candidate gene. By screening the EMS mutant library, we identified an additional mn6 allelic mutant (mn6-2). In the mn6-2 mutant, a G/A transition changes a Trp residue in exon 6 of GRMZM2G035526_P01 to a stop codon, resulting in a truncated protein (Supplemental Figure S6). Mature seeds of the mn6-2 mutant were smaller than normal sibling kernels and showed a similar phenotype to seeds of the mn6-1 mutant (Figure 3D). The mn6-2 mutation behaved as a single recessive trait. An allelism test was performed between mn6/+ and mn6-2/+. We applied mn6/+ pollen to the stigmas of mn6-2/+ ears and observed that the ears of (mn6/+ × mn6-2/+) heterozygotes showed a 1:4 segregation ratio of miniature:normal kernels (Figure 3E). These data suggested that the candidate gene GRMZM2G035526 was indeed responsible for the mn6 mutant phenotype.

Mn6 encodes a protein of 180 amino acid residues with Gly replaced by Ser at position 116 in mn6-1 in comparison with the WT protein, whereas in mn6-2 the G/A transition changes a Trp residue in exon 6 of GRMZM2G035526-p01 to a stop codon. Using an antibody (anti-Mn6) raised against a peptide consisting of acids 45–140 region of GRMZM2G035526-p01, an apparent molecular weight of approximately 20-kDa protein was detected in the WT and mn6-1 kernels but not in mn6-2 mature kernels (Figure 3F). Given that Mn6 expression was negligible in the mn6-2 mutant and the kernel phenotype of the mn6-2 mutant, namely the degree of reduction in kernel size and 100-grain weight, is more severe than that of the mn6-1 mutant (Figures 1, A and 3, D;Supplemental Figure S2), we used the mn6-2 mutant as the experimental material in subsequent analyses.

Mn6 is preferentially expressed in developing kernels

The spatial expression pattern of Mn6 was examined using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR; Figure 4A) and our previously published RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data (Chen et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2019; Figure 4B;Supplemental Figure S7A). The relative transcript level of Mn6 was highest in immature kernels, but low transcript levels were detected in other tissues analyzed. During kernel development, the Mn6 expression began to increase at 6 DAP and thereafter sharply increased and peaked at approximately 10 DAP, and then gradually decreased until 32 DAP. Mn6 was preferentially expressed in the endosperm during 6–10 DAP. The 6–10 DAP is the critical time for the endosperm differentiates into four main cell starchy endosperm, aleurone, embryo-surrounding region, and BETL (Sabelli and Larkins, 2009; Yi et al., 2019). Although the period of early endosperm development is much shorter than the mid (filling) and late (dehydration) phases, the endosperm cell differentiation stages are critical steps in endosperm formation in maize and many other species (Doll et al., 2017). By analyzing the RNA-seq data for subregions of the maize B73 seed at 8 DAP (Zhan et al., 2015), we determined that the Mn6 transcript level was higher in the BETL and embryo-surrounding region, intermediate in the aleurone, central starchy endosperm, conducting zone, and placento-chalazal region, and lower in embryo, nucellus, pericarp, and pedicel (Supplemental Figure S7B).

Figure 4.

Expression pattern of Mn6. (A) Expression pattern of Mn6 analyzed by real-time quantitative PCR. All materials were sampled from maize “B73”. Root and leaf samples were collected from seedlings at the three-leaf stage, and stem samples were collected at the seven-leaf stage. The relative expression levels were normalized against Zea mays actin1 (EU961034.1). RT-qPCR values for Mn6 were means of three technical replicates. Error bars represented the SD. (B) Transcript level (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) for Mn6 across developmental stages in the embryo, endosperm, intact seed, and nonseed.

We also used the immunoblot to test the Mn6 protein accumulation in the seed of WT (B73) at 6, 10, 12, 14 DAP. The result shows that the Mn6 protein is continue to accumulate at 12 and 14 DAP (Supplemental Figure S8). It suggested that the Mn6 protein is more stable and persists much longer than the transcript. The preferential expression during endosperm development in maize B73 suggested that Mn6 may play an important role in the endosperm development.

Mn6 encodes an ER type I signal peptidase of the S26 family

Genomics data obtained from the MaizeGDB (http://www.maizeGDB.org) databases showed that the transcribed region of Mn6 was 3,169 bp and included seven introns and eight exons. The longest identified mature transcript comprised 1,089 bp with 543 bp of coding sequence and noncoding regions of 177 and 369 bp at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The full-length protein product is expected to contain 180 amino acid residues.

Mn6 encodes a putative SPase I protein with a S26 family conserved domain composed of 154 amino acid residues (23–176; Supplemental Figure S9A). A topological and secondary structure analysis showed that the single transmembrane helices of Mn6 were created by amino acids 19–41 (Supplemental Figure S9B). We aligned the full-length sequences of S26 family proteins and constructed a phylogenetic tree for members from the genomes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis, humans, and the yeast S. cerevisiae (Figure 5A). In eukaryotes, the family of S26 SPases includes type I SPases predicted to be localized in the ER, mitochondria, and chloroplasts (Rawlings et al., 2006). Mn6 was grouped in Clade I, which was composed of three reported ER SPase I proteins, namely yeast SEC11, and human SEC11A and SEC11C (Figure 5A). Clade I also contained two Arabidopsis SPases, three rice SPases, and three maize SPases, which suggested that ER SPase function was conserved among the five species. ER SPases use a unique catalytic mechanism involving Ser and His residues. Residues Ser 44 (box B), His 83 (box D), Asp 103 (box E), and Asp 109 (box E; Figure 5B) in yeast SEC11 are essential for ER SPase catalytic preprotein processing in vivo (VanValkenburgh et al., 1999). These four catalysis-related residues in SEC11 were conserved in Mn6 (Figure 5B), which suggested that Mn6 might exhibit ER SPase I catalytic ability.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis and subcellular localization of Mn6. (A) The Mn6 protein and sequences of the full-length S26 family proteins from the genomes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis, humans, and yeast downloaded from the MEROPS database and aligned using ClustaIX2. The MEGA 7.0 was used to construct the phylogenetic tree. Distances were estimated with the neighbor-joining algorithm. Bootstrap support values are indicated beside branches. The GenBank numbers of the S26 family proteins were used to construct the phylogenetic tree shown in Table S1. (B) Conserved residues in boxes in the homologous SPase subunits from Clade I. The catalytic Ser 44 and His 83 residues (yeast SEC11) are showed by purple bars and with an asterisk. The mutation site in mn6-1 and the same site in other Clade I proteins are indicated by gray bars and with a number. The consensus sequence is displayed below each box. (C) Subcellular localization of Mn6 in maize protoplasts. GFP (the upper half of C) or Mn6-GFP (the bottom half of figure C) were co-transformed with an ER retention signal Lys–Asp–Glu–Leu–RFP (KEDL-RFP) into protoplasts prepared from etiolated maize seedlings of three-leaf-stage. Bar = 10 μm.

Gene cloning and phylogenetic analysis indicated that the Mn6 mature protein might be localized in the ER membrane. To determine the subcellular localization of Mn6, we used Mn6-green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter, which harbored a globular tail domain fused with the GFP gene at the Mn6 C-terminus, in addition to the ER retention signal KEDL (Lys–Asp–Glu–Leu) fused to the red fluorescent protein (RFP) gene as a positive control. We co-expressed Mn6-GFP with the ER marker (KDEL-RFP) in maize protoplasts, and the results showed that Mn6-GFP green (GFP) spherical vesicles were co-localized with the red (RFP) ER retention signal around the nucleus (Figure 5C), suggested that Mn6 was localized in the ER. In contrast, consistent with previous reports (Qi et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018) that the GFP signal of the blank control was detected throughout the protoplast in both nucleus and cytoplasm. These data provided further evidence that Mn6 protein is an ER SPase I.

Mn6 is the predominant S26 family ER SPase I that affects maize seed development

The maize genome contains two additional genes that encode S26 family ER SPase I proteins, namely ZmSigP2 (GRMZM2G067080) and ZmSigP3 (GRMZM2G307088), of which the products show high amino acid sequence similarity with Mn6 (ZmSigP1; Figure 5A). These two additional SPase I proteins contained the four catalysis-related residues: Ser 44 (box B), His 83 (box D), and Asp 103 and Asp 109 (box E; Figure 5B). Overall, Mn6 and ZmSigP2 showed 98% identity at the amino acid level, whereas Mn6 and ZmSigP3 showed 69% identity. According to a gene expression database (Chen et al., 2014), the expression patterns of ZmSigP2 and Mn6 were consistent in a variety of tissues. However, the expression level of ZmSigP2 in the majority of tissues was lower than that of Mn6, whereas the expression of ZmSigP3 was low in each of the tissues analyzed, including seed and non-seed samples (Supplemental Figure S10). We also test the expression of ZmSigP2 and ZmSigP3 in the mutant (mn6-2) background, not as the expression of ZmsigP1 (Mn6), which was significantly changed between WT and mn6-2 mutant at 6 and 8 DAP, the expression of ZmSigP2 and ZmSigP3 were almost unchanged between WT and mn6-2 mutant at 6 and 8 DAP (Supplemental Figure S11).

To examine whether ZmSigP2 and ZmSigP3 also function in maize seed development similar to Mn6, we generated ZmSigP2- and ZmSigP3-knockout (zmsigp2 and zmsigp3) mutants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Two homozygous knockout strains of ZmSigP2 (zmsigp2-1 and zmsigp2-2) were obtained (Supplemental Figure S12, A and B). A one-base deletion and 12-base deletion in exon 1 of ZmSigP2 was detected in zmsigp2-1 and zmsigp2-2, respectively. We also obtained two homozygous knockout strains of ZmSigP3 (zmsigp3-1 and zmsigp3-2; Supplemental Figure S12, C and D). Exon 1 of ZmSigP3 contained a one-base insertion and one-base deletion in zmsigp3-1 and zmsigp3-2, respectively. The mutations differed from the ZmSigp1 mutation that caused significant reduction in kernel size, and no obvious mutant phenotypes were observed in the kernels of the zmsigp2-1, zmsigp2-2, zmsigp3-1, and zmsigp3-2 mutants compared with the WT B73 kernel (Supplemental Figure S12E). In addition, the vegetative and reproductive stages of the zmsigp2-1, zmsigp2-2, zmsigp3-1, and zmsigp3-2 mutants were normal and no difference from the WT phenotype was observed. The corresponding heterozygous strains of zmsigp2-1, zmsigp2-2, zmsigp3-1, and zmsigp3-2 were obtained, and did not show segregation of kernel size after self-pollination. These data strongly suggested that Mn6 is the predominant S26 family ER SPase I that affects the maize seed development.

Mn6 is predominantly involved in processing carbohydrate metabolic related (GO: 0005975) proteins

To identify candidate substrates of Mn6, we performed mass spectrographic analysis and immunoprecipitation. For mass spectrographic analysis, we separated ER proteins using B73 kernels at 8 DAP and analyzed the proteome by tryptic digestion followed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry and peptide identification in accordance with proteomic data reporting guidelines (Bradshaw et al., 2006). In total, 2,655 proteins were identified (Supplemental Data Set S1), of which 324 (12%) proteins were annotated with signal peptides. Transgenic lines harboring full-length Mn6 tagged with Myelocytomatosis (MYC)were used to identify candidate proteins that interact with Mn6. Of the 940 proteins identified in the analysis that might interact with Mn6 (Supplemental Data Set S1), 418 (46%) were localized in the ER membrane. Among the 418 proteins, 68 (16%; Table 1) contained signal peptides, which implied that these proteins were potential substrates of Mn6.

Table 1.

Annotation of 68 potential genes encoding Mn6 substrates

| Gene_ID | Gene symbol | Gene_ID | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRMZM2G119689 | mn1 (Zm) | GRMZM2G346455 | phi002 (Zm) |

| GRMZM2G049693 | sku5 (At) | GRMZM2G065244 | |

| GRMZM2G144610 | endo1 (Zm) | GRMZM2G018275 | |

| GRMZM2G091481 | pdi1 (Zm) | GRMZM2G168588 | lym2 (At) |

| GRMZM2G462325 | ost1 (Zm) | GRMZM2G087245 | |

| GRMZM2G389173 | pdi8 (Zm) | GRMZM2G148925 | psei7 |

| GRMZM2G018416 | gpdl2 (At) | GRMZM2G009282 | trg1 (At) |

| GRMZM2G023392 | AY109506 (Zm) | GRMZM2G083725 | umc1664 (Zm) |

| GRMZM2G135968 | GRMZM2G039538 | sbt2 (Zm) | |

| GRMZM2G128865 | GRMZM2G320269 | ||

| GRMZM2G118362 | GRMZM2G099295 | ||

| GRMZM2G103179 | AC205471.4_FG008 | ||

| GRMZM2G001803 | iar1 (At) | GRMZM2G072240 | |

| GRMZM2G099528 | GRMZM2G114140 | ||

| GRMZM2G115750 | pco095480 (Zm) | GRMZM2G046729 | |

| GRMZM2G003752 | fla10 (At) | GRMZM2G022645 | |

| GRMZM2G022180 | clx2 (Zm) | AC231180.2_FG006 | |

| GRMZM2G136058 | GRMZM2G112792 | ||

| GRMZM2G140179 | GRMZM2G000566 | ||

| GRMZM2G042008 | GRMZM2G043584 | ||

| GRMZM2G013201 | GRMZM2G118873 | ||

| GRMZM2G377215 | rth3 (Zm) | GRMZM2G136106 | |

| GRMZM2G100288 | fer (At) | GRMZM2G168651 | hrg1 (Zm) |

| GRMZM2G144367 | sdf2 (At) | AC217293.3_FG007 | srk1 (Zm) |

| GRMZM2G077669 | GRMZM2G005633 | ctb1 (Zm) | |

| GRMZM2G106600 | GRMZM2G430902 | ||

| GRMZM2G023110 | rkl1 (At) | GRMZM2G008353 | |

| GRMZM2G005082 | GRMZM2G081583 | ||

| GRMZM2G173874 | Selt (At) | GRMZM2G128268 | |

| GRMZM5G872070 | B6T362 | ||

| GRMZM2G012224 | umc1118 (Zm) | A0A096TIT8 | |

| GRMZM2G089819 | imk2 (At) | B6SI04 | |

| GRMZM2G174883 | leg1 (Zm) | B4FY73 | |

| GRMZM2G315848 | pap24 (At) | B4FQ62 |

Annotations were retrieved from the MaizeGDB database. (Zm): genes reported in maize. (At): An annotation of the homologous gene of Arabidopsis thaliana.

Columns are blank if no corresponding data were available.

To analyze whether these potential substrates shared common features, we conducted a bioinformatic analysis of the 68 proteins. The protein sequences were divided into two parts: signal peptides and mature protein sequences (Supplemental Figure S13A). Sequence similarity was not observed among the mature protein sequences (Supplemental Figure S13B). The signal peptides of the 68 proteins showed a higher content of Leu residues and an Ala residue was more frequently present at the −1 and −3 positions (Ala–X–Ala) preceding the cleavage sites (Figure 6A). Further analysis revealed that 30 (44%) signal peptides contained the strict Ala–X–Ala residues at the −1 and −3 positions among the 68 proteins. This finding was consistent with previous reports that ER signal peptides tend to contain a higher number of Leu residues and cleavage follows the normal Ala–X–Ala processing rules (Paetzel et al., 2002; Auclair et al., 2012).

Figure 6.

Sequence characteristics and GO analysis of 68 potential substrates of Mn6. (A) Sequence characteristics of signal peptides. (B) Enriched GO terms in the molecular function category. (C) Enriched GO terms in the biological process category. These nodes in the image (B) and (C) are classified into nine levels which are associated with corresponding specific colors. The smaller of the term’s adjusted P-value, the more significant statistically, and the node’s color is darker and redder.

To investigate the functions of the potential substrates of Mn6, functional enrichment analysis was conducted to annotate the biological relevance of the potential substrate proteins using singular enrichment analysis from the AgriGO online toolkit (Du et al., 2010). In the molecular function category, the most significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) terms were “hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds” [GO: 0016798, false discovery rate {FDR} = 7.4 × 10−6] and “hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds” (GO: 0004553, FDR = 7.4 × 10−6). The term “hydrolase activity” (GO: 0016787, FDR = 0.0024) was also enriched (Figure 6B). In the biological process category, the potential substrates proteins were strongly enriched for GO terms associated with “cell wall organization or biogenesis” (GO: 0071554, FDR = 0.0016) and “carbohydrate metabolic process” (GO: 0005975, FDR = 0.00044; Figure 6C), which suggested that Mn6 was predominantly involved in cell wall organization and carbohydrate synthesis-related protein processing. With regard to the carbohydrate metabolic process, the 12 identified proteins included five annotated genes [Mn1, oligosaccharide transferase1 {OST1}, roothair defective3 {RTH3}, phi002, and chitinase B1 {CTB1}].

Mn6 is involved in Mn1 protein processing

In S. cerevisiae, invertase is the substrate of SEC11 (Böhni et al., 1988). In addition, signal peptides and SPase specificity are evolutionarily conserved (Watts et al., 1983; Paetzel et al., 2002; Tuteja, 2005). These results impelled us to investigate whether invertase is the substrate of Mn6 in maize. The 68 potential substrates of Mn6 included the typical invertase gene Mn1. Posttranscriptional suppression was reported in plsp1 (plastidic type I signal peptidase 1) mutant in Arabidopsis, which the transcript level of OE23, the substrate of Plsp1, were significantly lower in plsp1-1 as compared with that in the wild-type (Shipman-Roston et al., 2010). To explore whether the transcript level of invertase gene was reduced in mn6, we tested the expression of 72 genes that encode invertases identified in maize (Supplemental Data Set S2), only the expression of Mn1 was significantly changed between WT and mn6-2 kernels at 6 and 8 DAP, as determined from the RNA-seq data of the WT and mn6-2, and Mn1 expression was significantly reduced in the mn6-2 kernel (Figure 7A). The expression of Mn1 transcriptional level was consistent with that of Mn6, which was preferentially expressed in the developing kernel, especially in the endosperm at 6 and 8 DAP (Supplemental Figure S14). The amino acid sequence of Mn1 shows typical characteristics of an ER signal peptide with Ala–X–Ala residues at the −1 and −3 positions.

Figure 7.

Expression patterns of Mn6 and Mn1 and invertase activity in WT and mn6 mutant kernels. (A) Expression patterns of Mn6 and Mn1 in developing kernels at 6 and 8 DAP of mn6-2 mutant and WT, respectively. The result was determined from the RNA-seq data of the WT and mn6-2. Values are the means and standard errors (n = 2; ***P <0.001, Student’s t test). (B) Invertase activity in WT and mn6-2 mutant kernels at 12 DAP. Values are the means and standard errors (n = 3; ***P <0.001, Student’s t test). The results were reproducible in at least two sets of independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot comparing accumulation of Mn1 in the WT and mn6-2 mutant kernels at 8 DAP. Anti-actin was used as a sample loading control. The WT in this experiment was “B73”. Mutant samples came from mn6-2 self-homozygous plants. AL, aleurone; CSE, central starchy endosperm; CZ, conducting zone; EMB, embryo; ESR, embryo-surrounding region; NU, nucellus; PC, placento-chalazal region; PE, pericarp; PED, pedicel. Values are the means and standard errors (n = 3).

The kernels of mn6 and mn1 mutants show similar phenotypes in that the endosperm weight and size are severely reduced. As reported for the mn1 mutant, significant reduction in invertase activity in the endosperm would cause withdrawal of the pedicel from the developing endosperm and physical destruction of cells, and result in a gap forming between the pedicel and endosperm (Cheng et al., 1996). A visible gap between the endosperm and pedicel, similar to that reported in the homozygous mn1 mutant, was observed in the developing mn6-2 seed at 12 DAP (Figure 2A). Activities of soluble forms of invertase in kernel extracts at 12 DAP showed almost no difference between the wild-type and mn6-2 mutant, whereas cell-wall-bound invertase and total invertase activities were significantly decreased in the mn6-2 mutant compared with the wild-type (Figure 7B). Immunoblot analysis using anti-Mn1 antibodies indicated that the content of Mn1 mature protein in the mn6-2 mutant was substantially lower than that of the wild-type (Figure 7C). However, unprocessed Mn1 protein did not accumulate significantly in the mn6-2 mutant with defective processing of Mn1 protein. This is probably because the Mn1 precursor protein containing the signal peptide tended to be structurally unstable and subject to protein degradation.

Discussion

SPases I are indispensable enzymes involved in protein secretion pathways, and SPase I proteins are essential for the survival of single-cell organisms (Date, 1983; Cregg et al., 1996; Klug et al., 1997; Nahrstedt et al., 2004; Zhbanko et al., 2005; Taheri et al., 2010). The combined biochemical and genetic analyses presented here demonstrate that the maize Mn6 gene, which encodes an S26 family ER SPase I protein, is involved in maize endosperm development. Analysis of the sequence similarity of structurally conserved elements of SPases from other eukaryotic organisms showed that the Mn6 protein has high sequence similarity to ER SPase I, including yeast and human SEC11A. The Mn6 protein contained all five conserved domains characteristic of SPase I proteins (boxes A−E) and included the two distinctive catalysis-related amino acid residues (Ser and His) conserved in ER SPases I. Thus, we conclude that Mn6 encodes the catalytic subunit of an ER SPase I from maize.

Gly102 (box E) in Mn6 are irreplaceable during processing

To define the residues crucial for catalysis in ER SPases I, previous mutagenesis studies of SEC11 were performed by changing the residues conserved in the SPase family and histidine in the same position with the key lysine residues in the bacteria. It was observed that Ser 44 (box B), His 83 (box D), Asp 103 (box E), and Asp 109 (box E) were essential for preprotein treatment (VanValkenburgh et al., 1999). Green et al. mutated all Lys residues in the SEC11 protein, which are conserved in the eukaryotic SEC11 family and the essential glycol subunit SPC3, and determined that the Lys residues are not important for protein processing (Chen et al., 1999; VanValkenburgh et al., 1999). In the present study, we observed that an additional conserved residue (Gly) in box E mutated to Ser in Mn6 (mn6-1) and translation of a truncated Mn6 protein (mn6-2) can cause observable alterations in seed size and weight. In comparison with the mn6-1 mutant, the mn6-2 mutant showed a more severely reduced 100-grain weight. These results suggested that the conserved Gly residue in Box E in the ER SPase family is essential for processing preproteins in vivo. Mutation of this conserved Gly residue significantly reduced Mn6 activity but did not entirely eliminate activity.

The potential specificity of Mn6

The Mn6 is a gene encoding the ER SPase I, which mutation just affect endosperm development but not affect vegetative stage growth in maize. Our date showed that the Mn6 is predominantly involved in processing carbohydrate metabolic related proteins. These results suggested that the substrate of Mn6 should not be broad-spectrum and the protein processed by Mn6 had certain selectivity. This is consistent with the report of Plsp1 which is the plastidic SPase I in Arabidopsis thaliana, it can process lumenal protein OE33, but does not process OE17 (Shipman-Roston et al., 2010). However, the mechanism of the properties of Mn6 substrate selection needs further analysis. According to the conserved sequence (boxes A–E) of ER SPase I in human and yeast (Böhni et al., 1988; Paetzel et al., 2002), we found that there were two other ER SPase I in maize (ZmSigp2 and ZmSigp3), which did not affect maize seedling stage and seed development after mutation. It suggested that removal of the ER-targeting signal from other proteins may be mediated by other unidentified ER SPase I isoform, and/or an unconfirmed enzyme, that has a substrate preference different from that of Mn6. Alternatively, some ER-targeting signal may not specifically be removed but eventually degraded by ER proteases.

Invertase Mnl is a potential substrate of Mn6

Several lines of evidence from the present study indicate that Mnl is a substrate of Mn6. In S. cerevisiae, invertase is the substrate of the ER SPase SEC11 (Böhni et al., 1988). This finding is consistent with reports that signal peptides and SPase specificity are evolutionarily conserved (Watts et al., 1983; Paetzel et al., 2002; Tuteja, 2005); for example, the substrate specificity of an Escherichia coli SPase is similar to that of the ER SPase. This similarity is proved by the abilities of the E. coli enzyme to process preproinsulin and the ER SPC to cleave the M13 procoat protein (Watts et al., 1983). Among the 72 invertase genes identified in maize (Supplemental Figure S14 and Supplemental Data Set S2), only the Mn1 expression pattern was consistent with that of Mn6, which was preferentially expressed in the endosperm of developing kernels at 6 and 8 DAP. Mass spectrometric analysis revealed that Mn1 was localized in the ER membrane and interacted with Mn6. In addition, the signal peptide sequence of the Mn1 protein showed typical characteristics of ER signal peptide with Ala–X–Ala residues at the −1 and −3 positions.

Phenotypic analysis indicated that the mn6 and mn1 mutants show similar kernel phenotypes, namely severe reduction in endosperm weight and size leading to defective seed filling. Cytological and electron microscopic observations indicated that the degradation rate of the seed coat in the mn6 mutant was significantly lower than that of the wild-type. This phenotype of the mn1 mutant has not been reported previously. Invertase plays an important role in seed development, which was revealed in studies of sugar metabolism during the early development of legume seeds. In legume seeds, sugars are unloaded from the seed coat cells into the seed apoplast and are taken up by the apoplastically isolated embryo. Thus, reduction in cell wall invertase activity slows the degeneration of the parenchymatous tissue in the seed coat (Weber et al., 1997; Wobus and Weber, 1999). It is notable that a gap between the pedicel and endosperm is detectable at 12 DAP in mn1-1 and mn6 mutants. Formation of the gap is controlled by invertase activity in the endosperm (Cheng et al., 1996). As invertases are spatially and temporally the first enzymes in the developing endosperm to uptake sugars from maternal tissues (Cheng et al., 1996), it is not surprising that reduction or loss of such activity, as observed in the mn1 and mn6 mutants, is associated with significant reduction in mature seed weight. To date, signal peptidase activity of Mn6 has not been demonstrated in vitro. Indeed, the dramatic reduction in kernel size and weight in the mn6 mutant may arise as a secondary effect owing to alleviation of Mn1 activity by Mn6. The possibilities of increasing the seed filling rate by regulation of Mn6 activity or regulation of activity Mn6 and Mn1 simultaneously remain to be investigated.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The mn6-1 and mn6-2 mutants were isolated from a mutant library generated in our laboratory by EMS mutagenesis of the maize inbred line “B73”. The mutations were backcrossed into B73 genetic background for four times to remove other potential mutations induced by EMS treatment except for the mn6. Kernels were collected from self-pollinated ears of mn6/+ and mn6-2/+ plants in the B73 genetic background that showed segregation of 75% WT kernels (mn6/+ or +/+) and 25% homozygous mutant kernels. All plants were cultivated in the experimental field at the China Agricultural University (Beijing, China) under natural conditions. The transgenic lines were grown in a greenhouse under 28°C/24°C (day/night) and a 16-h photoperiod, without control of the relative humidity. Root, stem, and leaf samples were collected from at least three B73 plants at the V12 stage (Wang et al., 2010). Immature seeds were sampled at 0, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, and 32 DAP, embryos were collected at 12, 16, 24, and 32 DAP, and the endosperm was sampled at 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 24 DAP.

Light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy

For cytological observation, immature kernels of the wild-type (B73) and mn6-2 mutant were collected at 12 and 20 DAP, respectively. The samples were treated and observed as described previously (Li et al., 2018). For scanning electron microscopy, kernels of the wild-type (B73) and mn6-2 mutant were sampled at 20 DAP and from mature ears. Mature kernels were split in half from the middle of the embryo using two forceps. The kernel halves were fixed to stubs using double-sided carbon tape and coated with palladium–gold using an ion coater (Eiko IB-3, Ibaraki, Japan). The scanning electron microscope was used to observe samples (Hitachi S-3400N, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

Measurements of zein proteins

The zein proteins were extracted from whole endosperm of the maturity kernels as previously described (Liu et al., 2016; Song et al., 2019), protein bodies were extracted from WT and mn6-2 mutant were separated by sodium dodecyl–sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and stained with Coomassie Blue R.

Map-based cloning

The mn6 locus was mapped and cloned using 3,546 plants from a backcross population of mn6 with Mo17. First, 88 genetic markers, which were spaced at approximately 25-Mb intervals on the 10 chromosomes were used to preliminary pool and genotype DNA samples extracted from 46 miniature kernels. Genetic linkage with two markers on chromosome 6 (6-120 and 6-145.9) was determined. Molecular markers distributed throughout this chromosomal interval were used to genotype an additional 1,500 miniature kernel samples and the position of the mutation was localized to an 810-kb interval. Finally, a population of 2,000 miniature kernels was analyzed with the markers 6-137.60 and 6-138.41 and the mutated locus was localized to a 530-kb region (6-137.60 to 6-138.13 in Maize B73 RefGen_V2). Molecular markers used for fine mapping are listed in Supplemental Table S1. New markers were designed by comparing the genomic sequences of B73 and Mo17. The B73 genomic sequence (Schnable et al., 2009) and Mo17 genomic sequence (Sun et al., 2018) were downloaded from the MaizeGDB database. Mapping was performed based on a previously described method (Jander et al., 2002). The corresponding DNA fragments were amplified from mn6 alleles and WT plants (B73 and Mo17) using PrimeSTAR® Max DNA Polymerase (Takara).

Complementation of mn6

A plasmid carrying the Mn6 promoter (−2,000 before the “ATG” start codon) and full-length open reading frame of Mn6 fused to the MYC tag was constructed on the backbone of the pCAMBIA3301 vector, which carries a bar resistance marker. The resulting pMn6-myc construct was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of maize was conducted following a previously published protocol (Zhu et al., 2016). First, we transformed the B73 to obtain transgene-positive transformants. For molecular identification of transgenic plants, a marker (Mn6_test_F, Mn6_test_R) was designed to identify the Mn6 gene using the primer pair (Supplemental Table S2) which bind to the Mn6 coding sequence and MYC gene, respectively. The complementation events used in phenotypic analysis were confirmed by western blotting with anti-MYC antibodies.

The transgenic lines were crossed with homozygous mn6 mutants. Hybrids plants were genotyped to identify the Mn6 transgene and heterozygous mutation site for mn6. The double heterozygotes were self-pollinated to test whether the Mn6 full-length cDNA genetically complemented the mn6 mutation.

Plasmid construction for subcellular localization analysis

To generate a translational fusion between the Mn6 signal peptide and GFP, the full-length open reading frame of Mn6 without the stop codons and GFP was amplified by PCR with the primer Mn6-loc-F and Mn6-loc-R (Supplemental Table S2). The PCR products were introduced into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 by restriction enzyme digestion (SalI and SpeI) and ligation. The coding sequence of the ER retention signal KEDL (Lys–Asp–Glu–Leu) containing the digestion site of the restriction enzyme was synthesized and introduced into the pCAMBIA1300 vector. These binary constructs contained a 35S promoter driving constitutive expression of Mn6-GFP and the ER retention signal. Each plasmid (20 μg) was transformed into maize protoplasts. After culturing for 16–20 h, fluorescence was observed under a ZEISS LSM710 confocal laser microscope at the wavelength of 560–650 nm and 650–800 nm to detect GFP and MitoTracker red signals, respectively (Leica HQ).

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences for all proteins containing the S26 conserved domain from the genomes of maize, rice, Arabidopsis, humans, and yeast (S. cerevisiae) were downloaded from the MEROPS database (Rawlings et al., 2006). ClustaIX2 (Larkin et al., 2007) was used to align the selected protein sequences. A phylogenetic tree was constructed from the multiple sequence alignment with MEGA7 software using the neighbor-joining method (Kumar et al., 2016). A Poisson correction analysis was used to compute evolutionary distances. A bootstrap analysis with a heuristic search and 1,000 replicates was conducted to evaluate support for the tree topology.

Signal peptide prediction

We used the SignalP 4.1 server (Nielsen, 2017) to predict the presence and location of signal peptide cleavage sites in maize amino acid sequences. The method incorporates prediction of cleavage sites and signal peptide/nonsignal peptide prediction based on combination of several artificial neural networks.

Mn6 expression pattern analysis

To investigate the expression pattern of Mn6, RT-qPCR was performed using tissue samples from the maize (B73). Root and leaf samples were collected from seedlings at the three-leaf stage, and stem samples were collected at the seven-leaf stage. The Zea mays actin1 (EU961034.1) reference gene was used to normalize relative expression levels. Published RNA-seq data (Chen et al., 2014; Zhan et al., 2015) were used to analyze the Mn6 transcript level (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) across developmental stages in the embryo, endosperm, intact seed, and non-seed samples and for Mn6 in filial and maternal compartments of 8-DAP kernel.

RNA sequencing analysis

Two biological replicates of kernels from WT (B73) and mn6-2 mutant plants at 6 DAP and 8 DAP were sampled for RNA-seq analysis. Library construction and data analysis are carried out according to the previous research method (Chen et al., 2014). Genes with an adjusted q < 0.05, as determined by Cuffdiff software (Ghosh and Chan, 2016) and log2(fold change) > 1 were considered to be upregulated, whereas those genes with log2(fold change) less than −1 were considered to be downregulated. The AgriGO online tool (Du Z et al., 2010) was used to perform GO analysis.

ER protein fractionation and immunoblot analysis

For separation of ER proteins, samples were treated as described previously with slight modifications (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, powder (∼8 g) from kernels sampled at 8 DAP was suspended in resuspension buffer [10 mM Tris–Cl (pH 8.5), 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and proteinase inhibitor cocktail]. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 500g (for ER and protein body separation) for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was applied to discontinuous sucrose gradients for separation of ER proteins. In a discontinuous density centrifuge tube, 3 mL of 2-M sucrose was added first ensuring that the sucrose solution did not adhere to the wall of the tube. Then, 3 mL of 1.5-M sucrose was gently layered above the 2-M sucrose solution. Finally, 3 mL of 1-M sucrose was gently overlayed on the top of the gradient. Then 3.5-mL supernatant samples were added to each sucralose gradient ultracentrifuge tube, ensuring that the sucrose in the lowermost layer was disturbed as little as possible. After centrifugation at 156,000g for 60 min at 4°C, samples from the 1.0-M sucrose layer and from the layers at the interface of the 1.0-M/1.5-M and 1.5-M/2.0-M sucrose layers were carefully removed. The BiP rabbit antibody (C50B12; Cell Signaling Technology), which binds to an ER luminal binding protein, was used to test which layer was enriched with ER protein. Finally, the ER proteins, which were predominantly enriched in the interface between the 1.0-M/1.5-M sucrose layers, were used for mass spectrometry.

Protein samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted following standard protocols. The purified anti-sigp1 and myc antibodies were used at 1/500 dilution, and the α-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) and BiP antibody (C50B12; Cell Signaling Technology) were used at 1/1,000 dilution.

Statistical analysis

We used Microsoft Excel 2016 for data processing. Student’s t test and F test were performed to compare two samples using the data analysis module in Excel.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in Supplemental Table S3.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Vegetative period phenotype.

Supplemental Figure S2. Hundred-kernel weight of WT and mn6 mutant kernels.

Supplemental Figure S3. Characteristic analysis of zein proteins WT and mn6-2 mutant kernels

Supplemental Figure S4. Mutation sites for mn6-1.

Supplemental Figure S5. Genotyping of transgenic kernels.

Supplemental Figure S6. Mutation sites of mn6-2.

Supplemental Figure S7. Expression profile of Mn6 in early maize seed development and subregions of the maize “B73” seed at 8 DAP.

Supplemental Figure S8. Immunoblot comparing accumulation of Mn6.

Supplemental Figure S9. Conserved domain and transmembrane domains of Mn6.

Supplemental Figure S10. Expression profiles of ZmsigP1 (Mn6), ZmsigP2, and ZmsigP3.

Supplemental Figure S11. Expression profiles of ZmsigP2, and ZmsigP3 in the mn6-2 background.

Supplemental Figure S12. Analysis of Zmsigp2- and Zmsigp3-knockout transgenic maize.

Supplemental Figure S13. Sequence characteristics of 68 potential substrates of

Supplemental Figure S14. Expression pattern of 68 genes encoding Mn6 candidate substrates in different maize samples.

Supplemental Table S1. Sequence of polymorphic markers on chromosome 6.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table S3. The GenBank accession numbers of proteins used to construct the phylogenetic tree of the S26 family of proteins.

Supplemental Data Set S1. The detail information of ER proteins and candidate proteins that interact with Mn6.

Supplemental Data Set S2. The detail information of 72 genes that encode invertases identified in maize.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert McKenzie, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn/ac), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100404), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31421005), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101803), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671698, 32001558), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M620074).

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

W.S., J.L., Y.G., and F.Y. designed the experiments. F.Y., W.S., W.G., J.L., J.C., Y.C., L.H., and H.Z. performed the experiments. F.Y., W.S., and W.G. analyzed the data. F.Y., W.S., and J.L. wrote the manuscript.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys) is: Weibin Song (songweibin@cau.edu.cn).

References

- Auclair SM, Bhanu MK, Kendall DA (2012) Signal peptidase I: cleaving the way to mature proteins. Protein Sci 21: 13–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairl A, Muller P (1998) A second gene for type I signal peptidase in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, sipF, is located near genes involved in RNA processing and cell division. Mol Genet Genom 260: 346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhni PC, Deshaies RJ, Schekman RW (1988) SEC11 is required for signal peptide processing and yeast cell growth. J Cell Biol 106: 1035–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw RA, , Burlingame AL, , Carr S, , Aebersold R ( 2006) Reporting protein identification data: the next generation of guidelines. Mol Cell Proteomics 5: 787–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SJ, Shanker S, Chourey PS (2000) A point mutation at the Miniature1 seed locus reduces levels of the encoded protein, but not its mRNA, in maize. Mol Gen Genet 263: 367–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zeng B, Zhang M, Xie S, Wang G, Hauck A, Lai J (2014) Dynamic transcriptome landscape of maize embryo and endosperm development. Plant Physiol 166: 252–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Van Valkenburgh C, Fang H, Green N (1999) Signal peptides having standard and nonstandard cleavage sites can be processed by Imp1p of the mitochondrial inner membrane protease. J Biol Chem 274: 37750–37754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Taliercio EW, Chourey PS (1996) The Miniature1 seed locus of maize encodes a cell wall invertase required for normal development of endosperm and maternal cells in the pedicel. Plant Cell 8: 971–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourey PS, Jain M, Li Q, Carlson SJ (2006). Genetic control of cell wall invertases in developing endosperm of maize. Planta 223: 159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chourey PS, Li Q, Kumar D (2010) Sugar–hormone cross-talk in seed development: two redundant pathways of IAA biosynthesis are regulated differentially in the invertase-deficient miniature1 (mn1) seed mutant in maize. Mol Plant 3: 1026–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg KM, Wilding I, Black MT (1996) Molecular cloning and expression of the spsB gene encoding an essential type I signal peptidase from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 178: 5712–5718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbey RE, Lively MO, Bron S, Dijl JMV (1997) The chemistry and enzymology of the type I signal peptidases. Protein Sci 6: 1129–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalbey RE, Pei D, Ekici OD (2017) Signal peptidase enzymology and substrate specificity profiling. Methods Enzymol 584: 35–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date T (1983) Demonstration by a novel genetic technique that leader peptidase is an essential enzyme of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 154: 76–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll NM, Depège-Fargeix N, Rogowsky PM, Widiez T (2017) Signaling in early maize kernel development. Mol Plant 10: 375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z (2010) agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Res 38: W64–W70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Chan CK (2016) Analysis of RNA-seq data using TopHat and Cufflinks. Methods Mol Biol 1374: 339–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase GE, Kwak SJ, Chen R, Mardon G (2013) Drosophila signal peptidase complex member Spase12 is required for development and cell differentiation. PloS One 8: e60908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jander G, Norris SR, Rounsley SD, Bush DF, Levin IM, Last RL (2002) Arabidopsis map-based cloning in the post-genome era. Plant Physiol 129: 440–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang B, Xiong Y, Williams DS, Pozueta-Romero D, Chourey PS (2009). Miniature1 encoded cell wall invertase is essential for assembly and function of wall-in-growth in the maize endosperm transfer cell. Plant Physiol 151: 1366–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug G, Jager A, Heck C, Rauhut R (1997) Identification, sequence analysis, and expression of the lepB gene for a leader peptidase in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Genet Genom 253: 666–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33: 1870–1874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23: 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClere S, Schmelz EA, Chourey PS (2008) Cell wall invertase-deficient miniature1 kernels have altered phytohormone levels. Phytochemistry 69: 692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCLere S, Schmelz EA, Chourey PS (2010) Sugar levels regulate tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis in developing maize kernels. Plant Physiol 153: 306–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Liu H, Zhang Y, Kang T, Zhang L, Tong J, Xiao L, Zhang H (2013) Constitutive expression of cell wall invertase genes increases grain yield and starch content in maize. Plant Biotechnol J 11: 1080–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Gu W, Sun S, Chen Z, Chen J, Song W, Zhao H, Lai J (2018) Defective Kernel 39 encodes a PPR protein required for seed development in maize. J Integr Plant Biol 60: 45–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Shi J, Sun C, Gong H, Fan X, Qiu F, Huang X, Feng Q, Zheng X, Yuan N, et al. (2016). Gene duplication confers enhanced expression of 27-kDa γ-zein for endosperm modification in quality protein maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 4964–4969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Nelson OE Jr (1946). Miniature seed—a study in the development of a defective caryopsis in maize. Genetics 31: 525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midorikawa T, Endow JK, Dufour J, Zhu J, Inoue K (2014) Plastidic type I signal peptidase 1 is a redox-dependent thylakoidal processing peptidase. Plant J 80: 592–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ME, Chourey PS (1992) The maize invertase-deficient miniature-1 seed mutation is associated with aberrant pedicel and endosperm development. Plant Cell 4: 297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahrstedt H, Wittchen K, Rachman MA, Meinhardt F (2004) Identification and functional characterization of a type I signal peptidase gene of Bacillus megaterium DSM319. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64: 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuffer MG, Sheridan WF (1980) Defective kernel mutants of maize. I. Genetic and lethality studies. Genetics 95: 929–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H (2017). Predicting secretory proteins with SignalP. Methods Mol Biol 1611: 59–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oue N, Naito Y, Hayashi T, Takigahira M, Kawano-Nagatsuma A, Sentani K, Sakamoto N, Zarni OH, Uraoka N, Yanagihara K, et al. (2014). Signal peptidase complex 18, encoded by SEC11A, contributes to progression via TGF-alpha secretion in gastric cancer. Oncogene 33: 3918–3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetzel M, Dalbey RE, Strynadka NC (2000) The structure and mechanism of bacterial type I signal peptidases. A novel antibiotic target. Pharmacol Ther 87: 27–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetzel M, Karla A, Strynadka NC, Dalbey RE (2002) Signal peptidases. Chem Rev 102: 4549–4580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X, Li S, Zhu Y, Zhao Q, Zhu D, Yu J (2017) ZmDof3, a maize endosperm-specific Dof protein gene, regulates starch accumulation and aleurone development in maize endosperm. Plant Mol Biol 93: 7–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MS, Simser JA, Macaluso KR, Azad AF (2003) Molecular and functional analysis of the lepB gene, encoding a type I signal peptidase from Rickettsia rickettsii and Rickettsia typhi. J Bacteriol 185: 4578–4584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Barrett AJ (2006) MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D270–D272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabelli PA, Larkins BA (2009) The development of endosperm in grasses. Plant Physiol 149: 14–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, Liang C, Zhang J, Fulton L, Graves TA, et al. (2009) The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science 326: 1112–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman-Roston RL, Ruppel NJ, Damoc C, Phinney BS, Inoue K (2010) The significance of protein maturation by plastidic type I signal peptidase 1 for thylakoid development in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 152: 1297–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Zhu J, Zhao H, Li Y, Liu J, Zhang X, Huang L, Lai J (2019) OS1 functions in the allocation of nutrients between the endosperm and embryo in maize seeds. J Integr Plant Biol 61: 706–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinard P (1991) Miniature-3 (mn3): a viable miniature kernel mutant on chromsome 6. MNL, 16–17

- Sun S, Zhou Y, Chen J, Shi J, Zhao H, Zhao H, Song W, Zhang M, Cui Y, Dong X, et al. (2018) Extensive intraspecific gene order and gene structural variations between Mo17 and other maize genomes. Nat Genet 50: 1289–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri T, Salmanian AH, Gholami E, Doustdari F, Zahedifard F, Rafati S (2010) Leishmania major: disruption of signal peptidase type I and its consequences on survival, growth and infectivity. Exp Parasitol 126: 135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja R (2005). Type I signal peptidase: an overview. Arch Biochem Biophys 441: 107–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuteja R, Pradhan A, Sharma S (2008) Plasmodium falciparum signal peptidase is regulated by phosphorylation and required for intra-erythrocytic growth. Mol Biochem Parasitol 157: 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanValkenburgh C, Chen X, Mullins C, Fang H, Green N (1999) The catalytic mechanism of endoplasmic reticulum signal peptidase appears to be distinct from most eubacterial signal peptidases. J Biol Chem 274: 11519–11525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhar B, , Kladnik A, , Blejec A, , Chourey PS, , Dermastia M ( 2002) Cytometrical evidence that the loss of seed weight in theminiature1 seed mutant of maize is associated with reduced mitotic activity in the developing endosperm. Plant Physiol 129; 23–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, , Wang H, , Zhu J, , Zhang J, , Zhang X, , Wang F, , Tang Y, , Mei B, , Xu Z, , Song R (2010) An expression analysis of 57 transcription factors derived from ESTs of developing seeds in maize (Zea mays). Plant Cell Rep 29: 545–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Wang F, Wang G, Wang F, Zhang X, Zhong M, Zhang J, Lin D, Tang Y, Xu Z (2012) Opaque1 encodes a myosin XI motor protein that is required for endoplasmic reticulum motility and protein body formation in maize endosperm. Plant Cell 24: 3447–3462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, Wickner W, Zimmermann R (1983) M13 procoat and a pre-immunoglobulin share processing specificity but use different membrane receptor mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 2809–2813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobus U, Weber H (1999) Sugars as signal molecules in plant seed development. Biol Chem 380: 937–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi F, Gu W, Chen J, Song N, Gao X, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Ma X, Song W, Zhao H, et al. (2019) High temporal-resolution transcriptome landscape of early maize seed development. Plant Cell 31: 974–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J, Thakare D, Ma C, Lloyd A, Nixon NM, Arakaki AM, Burnett WJ, Logan KO, Wang D, Wang X, et al. (2015) RNA sequencing of laser-capture microdissected compartments of the maize kernel identifies regulatory modules associated with endosperm cell differentiation. Plant Cell 27: 513–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Xia Y (2014) ER type I signal peptidase subunit (LmSPC1) is essential for the survival of Locusta migratoria manilensis and affects moulting, feeding, reproduction and embryonic development. Insect Mol Biol 23: 269–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhbanko M, Zinchenko V, Gutensohn M, Schierhorn A, Klosgen RB (2005) Inactivation of a predicted leader peptidase prevents photoautotrophic growth of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 187: 3071–3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Song N, Sun S, Yang W, Zhao H, Song W, Lai J (2016) Efficiency and inheritance of targeted mutagenesis in maize using CRISPR-Cas9. J Genet Genom 43: 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.