Abstract

The dynamics of leaf photosynthesis in fluctuating light affects carbon gain by plants. Mesophyll conductance (gm) limits CO2 assimilation rate (A) under the steady state, but the extent of this limitation under non-steady-state conditions is unknown. In the present study, we aimed to characterize the dynamics of gm and the limitations to A imposed by gas diffusional and biochemical processes under fluctuating light. The induction responses of A, stomatal conductance (gs), gm, and the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax) or electron transport (J) were investigated in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.)) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). We first characterized gm induction after a change from darkness to light. Each limitation to A imposed by gm, gs and Vcmax or J was significant during induction, indicating that gas diffusional and biochemical processes limit photosynthesis. Initially, gs imposed the greatest limitation to A, showing the slowest response under high light after long and short periods of darkness, assuming RuBP-carboxylation limitation. However, if RuBP-regeneration limitation was assumed, then J imposed the greatest limitation. gm did not vary much following short interruptions to light. The limitation to A imposed by gm was the smallest of all the limitations for most of the induction phase. This suggests that altering induction kinetics of mesophyll conductance would have little impact on A following a change in light. To enhance the carbon gain by plants under naturally dynamic light environments, attention should therefore be focused on faster stomatal opening or activation of electron transport.

Gas diffusional and biochemical processes impose significant limitations to CO2 assimilation during photosynthetic induction.

Introduction

Under field environments, light intensity fluctuates over seconds to minutes throughout the day due to changes in solar position, cloud cover, or self-shading in the plant canopy, which affects carbon gain via leaf photosynthesis (Pearcy and Way, 2012; Tanaka et al., 2019). The transition from low to high light induces a gradual increase in CO2 assimilation rate (A), which is termed “photosynthetic induction” (Pearcy, 1990). A is determined by the combination of CO2 diffusion from the atmosphere to the chloroplast stroma, and CO2 fixation in the chloroplast stroma. The CO2 diffusion pathway for photosynthesis consists of resistances through the leaf boundary layer, stomata, intercellular airspaces, and the components of mesophyll cells such as the cell wall, plasma membrane, cytosol, and chloroplast envelope and stroma (Evans et al., 2009). The conductance, that is the reciprocal of resistance, to gas diffusion via stomata (gs) has been shown to be a limiting factor of A under fluctuating light (Kaiser et al., 2016; Matthews et al., 2019; Papanatsiou et al., 2019; Shimadzu et al., 2019; Kimura et al., 2020; Yamori et al., 2020). Slow activation of electron transport, Calvin–Benson cycle enzymes, especially Rubisco, and sucrose synthesis can also impose a major limitation to A during photosynthetic induction (Stitt and Schreiber, 1988; Yamori et al., 2012, 2016; Carmo-Silva and Salvucci, 2013; Kaiser et al., 2016). Previous studies have highlighted that in addition to gs, the conductance to gas diffusion from intercellular airspaces to the chloroplast stroma (gm) imposes a significant limitation to A under steady-state conditions (Evans et al., 1986; Pons et al., 2009; Flexas et al., 2013). However, no studies have elucidated the limitation to A by gm under non-steady-state conditions following a change in light intensity. Characterizing the dynamics of gm and how it limits A under fluctuating light is crucial for understanding the physiological mechanisms regulating carbon gain by plants under field conditions.

Short-term responses of gm to changes in environmental factors such as CO2 concentration (Mizokami et al., 2019), temperature (Yamori et al., 2006; von Caemmerer and Evans, 2015), light intensity (Tazoe et al., 2009; Yamori et al., 2010), soil water content, and vapor pressure depression (Warren, 2008) have been determined. The response of gm to light intensity is still understudied as it varies between plant species and the methods used to estimate gm. It was reported that gm increased with increasing light intensity in chickpea and several Eucalyptus species (Campany et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2018; Shrestha et al., 2019) when estimated from concurrent measurements of gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination (Evans et al., 1986). On the contrary, gm was independent of light intensity in wheat and tobacco when estimated by the same method (Tazoe et al., 2009; Yamori et al., 2010). Both light-dependent or -independent responses of gm have been reported for the same plant species (Xiong et al., 2015, 2018; Carriquí et al., 2019) when estimated from concurrent measurements of gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence (Harley et al., 1992). Consequently, the nature of the light response of gm needs to be studied from a new angle.

Four methods have been developed to estimate gm based on (1) gas exchange measurements (Ethier and Livingston, 2004), the concurrent measurement of gas exchange with chlorophyll fluorescence to estimate the electron transport rate (J); the (2) constant and (3) variable J methods (Harley et al., 1992), or (4) the concurrent measurement of gas exchange with carbon isotope discrimination (Evans et al., 1986). Although the variable J method is most commonly used to analyze the light response of gm, estimating gm under fluctuating light is problematic due to potential changes in alternative electron transport, ATP and NADPH production, and leaf absorptance. The concurrent measurement of gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination using tunable diode laser (TDL) spectroscopy has enabled the dynamic measurement of gm under changing CO2 or temperature conditions, although estimated gm can be more variable when A is low (Tazoe et al., 2011; Evans and von Caemmerer, 2013). Therefore, a TDL system should enable the dynamics of gm to be estimated following a step change in light intensity.

In the present study, we aimed to characterize the dynamics of gm and its limitation of A while considering stomatal opening, Rubisco activation, and electron transport after a step change in light. Measurements were made under 2% O2 conditions with a gas exchange system coupled to a TDL that measured carbon isotope discrimination. Leaves of two model plants, Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), which are commonly used for modeling analyses of leaf photosynthesis (Bernacchi et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2013), were examined under several conditions with step changes in light. The limitations to A imposed by gs, gm, and the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax) or the electron transport rate (J) were analyzed based on the biochemical model for C3 photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980). The dynamic response of gm and carbon gain during photosynthetic induction was revealed.

Results

Sensitivity of mesophyll conductance after a step change in light

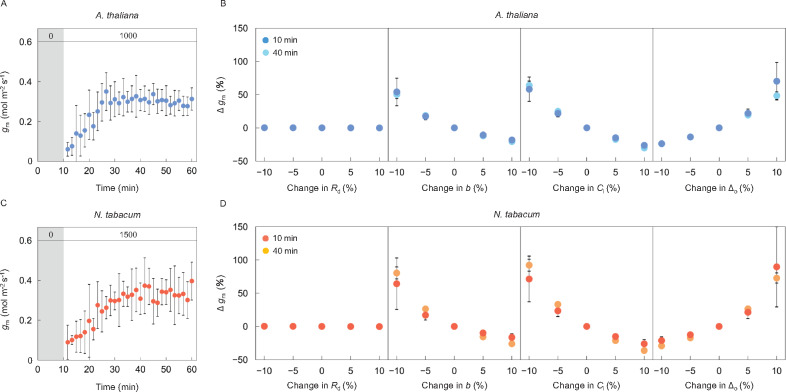

The induction response of gm was observed after changing from overnight darkness to high light of 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 in Arabidopsis (Figure 1A) or 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1 in tobacco (Figure 1C), in air containing 2% O2 and 400 µmol mol−1 CO2. In the present study, unreasonable values of gm (i.e. gm ≥ 0.8 or gm ≤ 0) were eliminated prior to the calculation of the corresponding average values at each time point (Figure 1). The induction curves of gm including or eliminating unreasonable values were shown in Supplemental Figure S1, which reveals that data elimination had only a minor effect on the evaluation of gm induction. The calculation of gm depends on the values assumed for various parameters and is sensitive to measurement errors. Thus, we began by examining the sensitivity of apparent gm to changes in the four parameters in Equation 1, day respiration (Rd), discrimination in the carboxylation reactions by Rubisco and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (b), CO2 concentration in intercellular airspaces (Ci), and the observed fractionation (Δo), under steady and non-steady-state conditions. Changing Rd from -10% to +10% of the true value had little impact on gm, which varied by only -0.3% to 0.3% in either Arabidopsis (Figure 1B) or tobacco (Figure 1D). By contrast, gm varied by -36.2% to 92.1% when b, Ci, or Δo were varied by -10% to +10% of their true value. The potential error in Δo was initially about 1.5‰, and gradually decreased to 0.2‰–0.3‰ during photosynthetic induction in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Supplemental Figure S2). The potential uncertainty in Δo, defined as the ratio of potential error in Δo to the actual value of Δo at each time point, was initially 13% in Arabidopsis and 10% in tobacco and gradually decreased to 1%–2% in both species. This lies within the variation range shown for the sensitivity analysis (maximum 20%). In both species, the estimated sensitivity of gm to errors in parameters were similar at 10 and 40 min after changing from darkness to high light, representing nonsteady and steady states, respectively.

Figure 1.

Potential variability in the estimation of mesophyll conductance after a step change in light. Mesophyll conductance (gm) was measured every 100 s (A) for 10 min in darkness followed by 50 min under a PPFD of 1,000-μmol photons m−2 s−1 in Arabidopsis (blue), and (C) for 10 min in darkness followed by 50 min under a PPFD of 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 in tobacco (red), respectively. CO2 concentration and air temperature in the leaf chamber were set to 400 µmol mol−1 and 24°C, respectively. A sensitivity of gm was evaluated in (B) Arabidopsis and (D) tobacco by changing the value of day respiration rate in the light (Rd), CO2 concentration in intercellular airspaces (Ci), discrimination in the carboxylation reaction by Rubisco and PEPC (b), and the observed carbon isotope discrimination (Δo) using data collected 10 (dark) and 40 min (pale) after the light was turned on. The vertical bars on each plot indicate the standard deviation (A, C) or standard error (B, D) with 6–8 replicate leaves for Arabidopsis and 3–6 leaves for tobacco. The numbers (0, 1,000, and 1,500) in the grey and white boxes at the top of (A) and (C) indicate the light intensity.

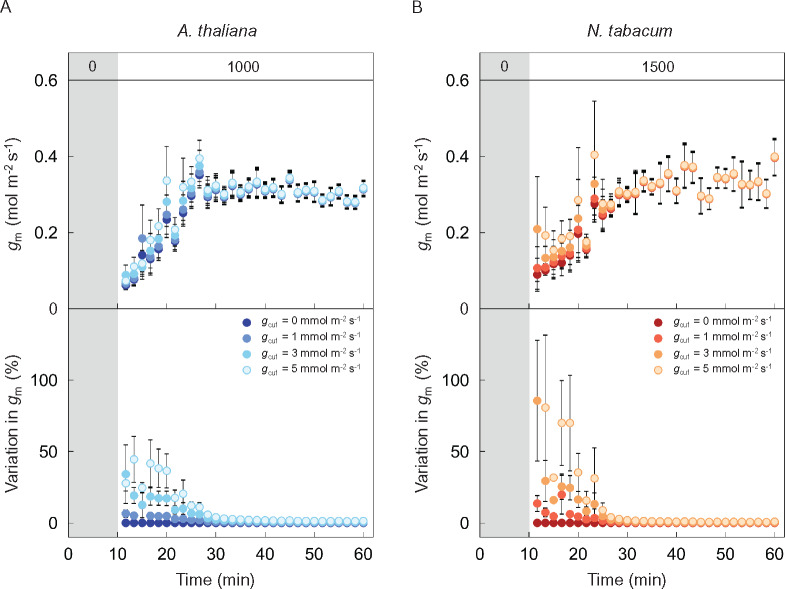

In addition, the value assumed for cuticular conductance to gas diffusion (gcut) would influence the calculation of Ci when gs is low. In turn, this would affect the estimation of gm and how it changes during induction. We therefore examined the influence of gcut on apparent gm during induction in Arabidopsis and tobacco. When Ci was calculated assuming gcut of 0, 1, 3, or 5 mmol m−2 s−1, estimated non-steady-state gm varied up to 45% in Arabidopsis (Figure 2A) and 86% in tobacco (Figure 2B). Greater gcut resulted in greater gm during photosynthetic induction when gs was small. However, varying the assumed value of gcut had little impact on the relative importance of gm during induction in either plant species. Also, varying gcut had no impact on steady-state estimates of gm.

Figure 2.

Effects of cuticular conductance on estimated mesophyll conductance values. Variation in mesophyll conductance (gm) was calculated assuming a cuticular conductance (gcut) of 0 (dark), 1 (slightly dark), 3 (slightly pale), or 5 (pale) mmol m−2 s−1 in (A) Arabidopsis (blue) and (B) tobacco (red), respectively, with the dataset shown in Figure 1, A and C. The vertical bars on each plot indicate the standard error with 6–8 replicate leaves for Arabidopsis and 3–6 leaves for tobacco. Grey boxes in each figure indicate the initial period of darkness. The numbers (0, 1,000, and 1,500) in grey and white boxes at the top of (A) and (B) indicate the light intensity.

Dynamics of photosynthetic parameters after a step change in light from overnight darkness to high or low light

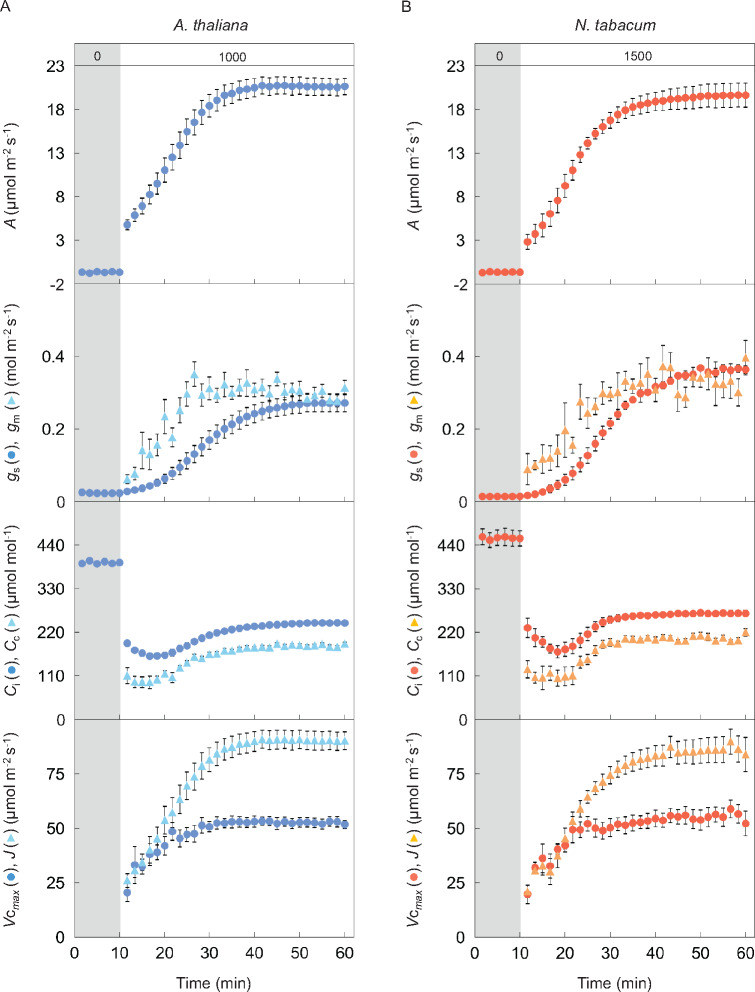

The induction responses of A, gs, and gm were shown after changing from overnight darkness to high light (1,000 or 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1) in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Figure 3). According to the biochemical model of C3 photosynthesis, A can be limited by RuBP carboxylation or regeneration (Farquhar et al., 1980). The responses of Vcmax and J were shown assuming either RuBP-carboxylation or RuBP-regeneration limiting conditions, respectively. The speed of response for each parameter varied (Table 1). The time taken for each parameter to reach 50% and 90% of the maximum value (t50 and t90, respectively) increased in the order of Vcmax, gm, J, A, and gs, and those for gs were significantly longer than those for the other parameters in both plant species (P < 0.05). These results indicate that stomatal conductance was the slowest to respond to a change in light out of all the parameters. There was no significant variation in t50 and t90 values between the two plant species for any of the parameters. The responses of Ci and Cc following the step increase in light were similar for both plant species.

Figure 3.

Response of CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal and mesophyll conductance, CO2 concentration in the intercellular airspaces and chloroplast stroma, the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation, and electron transport after changing from darkness to high light. A CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal (gs; dark circle) and mesophyll conductance (gm; pale triangle) to CO2, and CO2 concentration in intercellular airspaces (Ci; dark circle) and chloroplast stroma (Cc; pale triangle) were measured every 100 s under the light condition of (A) a PPFD of 0 and 1,000-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10 min and 50 min in Arabidopsis (blue), and (B) a PPFD of 0 and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10 and 50 min in tobacco (red), respectively. The maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax; dark circle) and electron transport (J; pale triangle) were also estimated assuming RuBP-carboxylation or regeneration limiting conditions according to the biochemical model for C3 photosynthesis. CO2 concentration and air temperature in the leaf chamber were set to 400 µmol mol−1 and 24°C, respectively. The vertical bars on each plot indicate the standard error with 6–8 replicate leaves for Arabidopsis and 3–6 leaves for tobacco. Grey boxes in each figure indicate the initial period of darkness. The numbers (0, 1,000, and 1,500) in the grey and white boxes at the top of (A) and (B) indicate the light intensity.

Table 1.

Comparison of the response speed for CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal and mesophyll conductance, and the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation in Arabidopsis and tobacco

| Parameters | Arabidopsis |

Tobacco |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t 50 (min) | t 90 (min) | t 50 (min) | t 90 (min) | |

| A | 9.5 ± 0.8 b | 19.7 ± 1.5 b | 10.0 ± 1.4 a | 19.0 ± 2.1 a |

| g s | 18.8 ± 1.0 c | 29.7 ± 1.4 c | 18.5 ± 0.9 b | 28.9 ± 0.8 b |

| g m | 8.7 ± 1.2 b | 14.8 ± 1.8 ab | 9.2 ± 2.2 a | 17.1 ± 3.3 a |

| V cmax | 4.3 ± 0.5 a | 9.7 ± 1.2 a | 5.3 ± 1.0 a | 11.0 ± 3.0 a |

| J | 8.9 ± 0.8 b | 19.2 ± 1.5 b | 9.5 ± 1.4 a | 18.6 ± 2.1 a |

t 50 and t90 are the times when CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal (gs) and mesophyll (gm) conductance to CO2, the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax), and the electron transport rate (J) reached 50% and 90% of their maximum value, respectively, after the step change in light. Different letters indicate significant variation in t50 or t90 between the five parameters (P < 0.05) according to the Tukey–Kramer test.

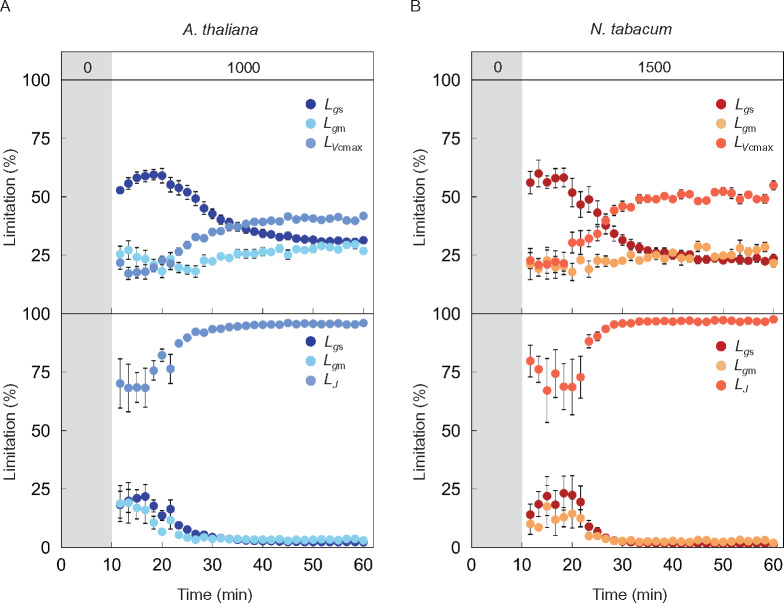

We evaluated the relative limitations to A imposed by gs (Lgs), gm (Lgm), and Vcmax (LVcmax) or J (LJ), defined as the relative change in A for a relative change in the four parameters, during photosynthetic induction with the dataset shown in Figure 3 (Figure 4). Assuming the RuBP-carboxylation limiting condition, Lgs was 60% during the initial 10 min after switching on the light, then decreased gradually to 20%–30%. Lgm decreased slightly before increasing to within the range of 20%–30% during photosynthetic induction in Arabidopsis and tobacco. LVcmax increased from 20% to 40%–50% in both plant species after switching on the light. gs imposed the greatest limitation during the initial 25 min in Arabidopsis and 15 min in tobacco, while Vcmax imposed the greatest limitation during the latter phase in both plant species. gm imposed the least limitation during photosynthetic induction except during the initial 10 min. If RuBP regeneration was assumed to limit Rubisco, Lgs and Lgm were initially 20%–25% and gradually decreased to 2%–3% during induction in a similar manner for both plant species. J imposed much greater limitation to A than gs and gm under both steady and nonsteady states.

Figure 4.

Gas diffusional and biochemical limitations of CO2 assimilation rate after changing from darkness to high light in Arabidopsis and tobacco. The limitations to CO2 assimilation rate (A) imposed by stomatal conductance (Lgs; dark), mesophyll conductance (Lgm; pale) and biochemical processes were evaluated in (A) Arabidopsis (blue) and (B) tobacco (red), respectively, with the dataset shown in Figure 3. Biochemical limitations assumed either RuBP-carboxylation (upper panels, LVcmax) or RuBP-regeneration (bottom panels, LJ) limiting conditions. The vertical bars on each symbol indicate the standard error with 6–8 replicate leaves for Arabidopsis and 3–6 leaves for tobacco. Grey boxes in each figure represent the initial period of darkness. The numbers (0, 1,000, and 1,500) in the grey and white boxes at the top of (A) and (B) indicate the light intensity.

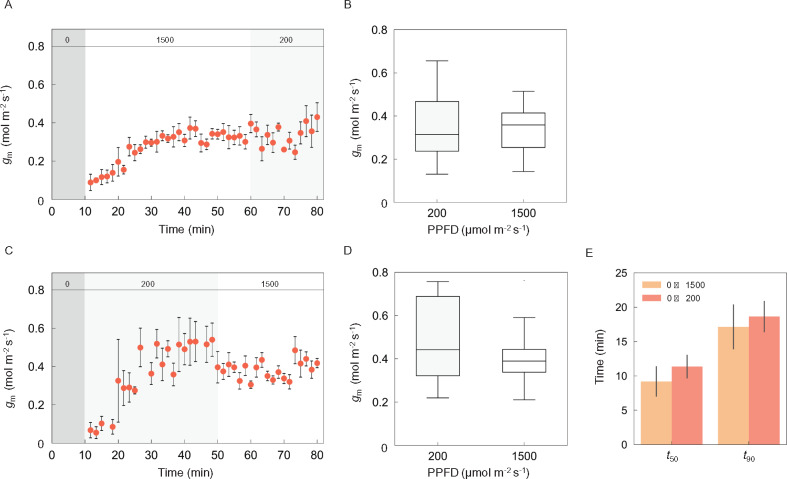

We investigated the responses of gm after changing from darkness to high (1,500 µmol m−2 s−1) or low light (200 µmol m−2 s−1) followed by a reciprocal transition between high and low light, in tobacco. The induction response of gm is shown after changing from overnight darkness to high light (Figure 5A) or low light (Figure 5C). Subsequently, upon changing from high to low light or low to high light, gm did not change, while A, gs, Ci, and Cc changed (Figure 5, A and B, Supplemental Figure S3). The t50 and t90 values for gm did not differ between the two light conditions (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Responses of mesophyll conductance following transitions to low and high light for tobacco. Mesophyll conductance (gm) was measured every 100 s under the light sequence (A) from darkness (10 min) to a PPFD of 1,500 (50 min) then 200 (20 min) or (C) from darkness (10 min) to 200 (40 min) then 1,500-µmol photons m−2 s−1 (30 min). CO2 concentration and air temperature in the chamber were set to 400 µmol mol−1 and 24°C, respectively. Grey and pale-grey boxes in each figure represent the periods of darkness and 200-µmol photons m−2 s−1, respectively. The numbers (0, 200, and 1,500) in the grey, pale-grey, and white boxes at the top of (A) and (C) indicate the light intensity. The variation in gm under steady state was compared between the light intensity of a PPFD of 200 (pale-grey) and 1,500 (white)-µmol photons m−2 s−1 under the light sequence (B) from darkness (10 min) to 1,500 (50 min) then 200 (20 min) or (D) from darkness (10 min) to 200 (40 min) then 1,500-µmol photons m−2 s−1 (30 min). (E) The time taken for gm to reach 50% (t50) and 90% (t90) of their maximum value was compared between two light sequences. The vertical bars on each plot and columns in (A), (C), and € indicate the standard error with 3–6 replicate leaves for tobacco.

Dynamics of the photosynthetic parameters after a step change from short or long periods of darkness to high light

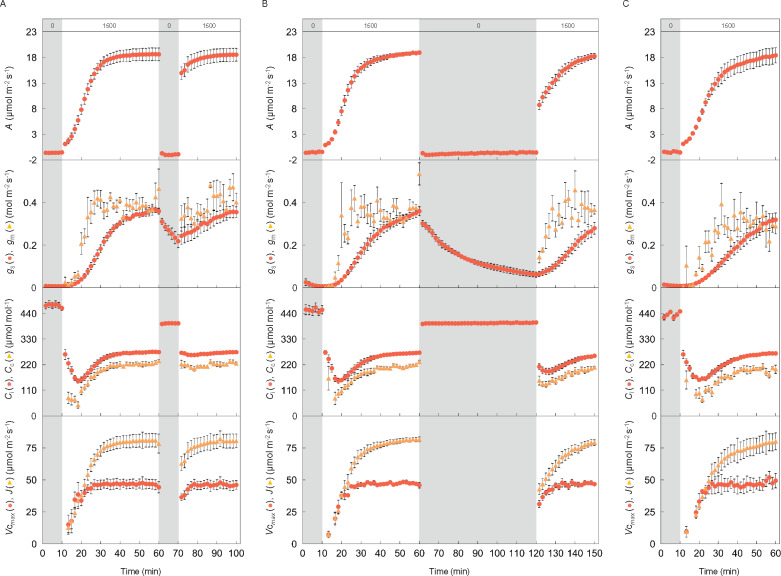

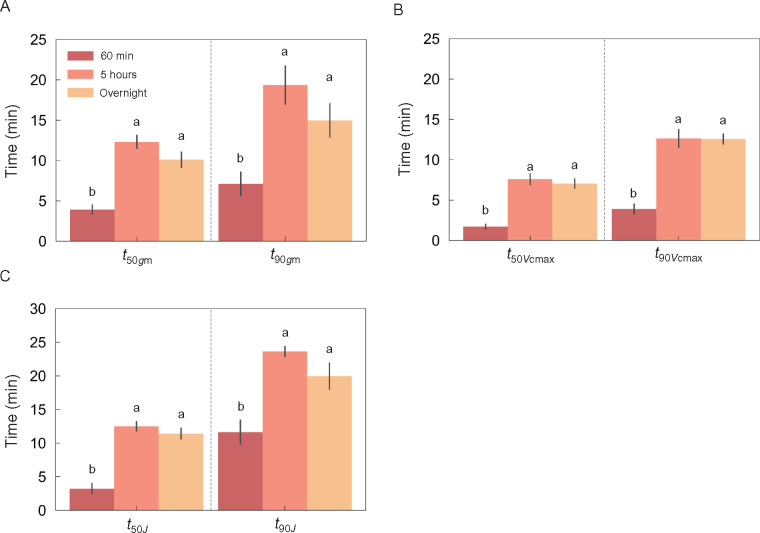

To understand how quickly induction relaxed, tobacco leaves were subjected to 50 min of high light followed by darkness for 10 min or 60 min and responses of A, gs, gm, Vcmax, and J were analyzed during the second period of high light (Figure 6, A and B). The speed of response for all the parameters was slower as the intervening dark period lengthened. The t50 and t90 values for gm, Vcmax, and J were significantly shorter under high light following a 60 min period of darkness compared with after a 5 h period of darkness or overnight darkness (Figure 7). The speed of responses for the parameters were similar following 5 h darkness or overnight darkness (Figure 6, A and C) with no significant variation in t50 and t90 for gm, Vcmax, and J under those light conditions (Figure 7). Vcmax had the fastest response of all of the parameters under any light condition (Table 1 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Responses of CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal and mesophyll conductance, CO2 concentration in intercellular airspaces and chloroplast stroma, the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation, and electron transport after short or long periods of darkness. CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal (gs; dark circle), and mesophyll conductance (gm; pale triangle) to CO2, and CO2 concentration in the intercellular airspaces (Ci; dark circle) and chloroplast stroma (Cc; pale triangle) were measured every 100 s under the light condition of (A) a PPFD of 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 10, and 30 min, and (B) 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 60, and 30 min preceded by overnight-darkness, or (C) 2 h of sunlight followed by 5 h of darkness, then 0 and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10 and 50 min, respectively. The maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax; dark circle) and electron transport (J; pale triangle) were also estimated assuming RuBP-carboxylation or RuBP-regeneration limiting conditions. CO2 concentration and air temperature in the chamber were set to 400 µmol mol−1 and 24°C, respectively. The vertical bars on each plot indicate the standard error with 3–6 replicate leaves for tobacco. Grey boxes in each figure represent the periods of darkness. The numbers (0 and 1,500) in the grey and white boxes at the top of (A), (B), and (C) indicate the light intensity.

Figure 7.

Comparison of response speeds for mesophyll conductance and the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation in tobacco after changing from short or long periods of darkness to high light. The time taken for mesophyll conductance (gm) (A), and the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax) (B) and electron transport (J) (C) to reach 50% (t50) and 90% (t90) of their maximum value was compared between inductions under high light after darkness for 60 min or 5 h following illumination for more than 1 h, or overnight darkness. The vertical bars on each plot indicate the standard error with 3–6 replicate leaves for tobacco. Different letters on each column indicate significant variation in t50 or t90 of three parameters at P < 0.05 according to Tukey–Kramer test.

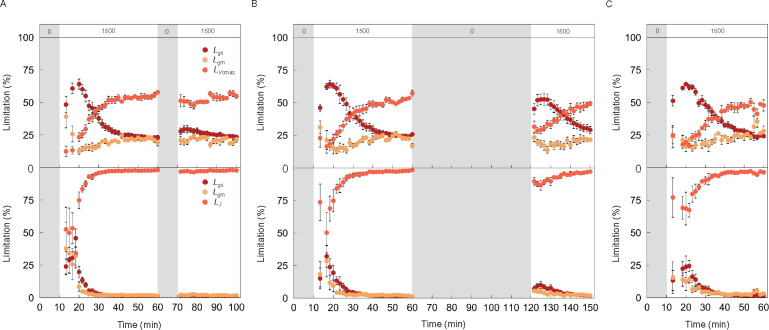

Finally, we evaluated Lgs, Lgm, and Lvcmax or LJ with the dataset shown in Figure 6 (Figure 8). The dynamics of gas diffusional (Lgs and Lgm) and biochemical (Lvcmax and LJ) limitations were similar to those shown in Figure 4 after changing from overnight darkness to high light. Following a 10 min dark interruption after 50 min in high light, all the limitations scarcely changed under high light, and Lvcmax was much larger than Lgs and Lgm, assuming the RuBP-carboxylation limiting condition (Figure 8A). However, those limitations were affected by longer dark interruptions (Figure 8, B and C). During induction subsequent to darkness for 60 min, 5 h, or overnight, initially Lgs was dominant but then decreased as Lvcmax increased, while Lgm changed only slightly. Stomata imposed the greatest limitation during the early phase of photosynthetic induction, while Vcmax imposed the greatest limitation during the latter phase under any of the light sequences, except for high light after 10 min darkness. Assuming the RuBP-regeneration limiting condition, 10 min and 60 min dark interruptions induced little or no changes in any of the limitations during induction, while 5 h dark interruption induced substantial changes in each limitation. Electron transport rate imposed the greatest limitation to A under both nonsteady and steady states under any of the light sequences.

Figure 8.

Gas diffusional and biochemical limitations of CO2 assimilation rate after changing from short or long periods of darkness to high light. The limitations to CO2 assimilation rate (A) imposed by stomatal conductance (Lgs; dark), mesophyll conductance (Lgm; pale), and biochemical processes were evaluated in tobacco with the dataset shown in Figure 6. Biochemical limitations assumed either RuBP carboxylation (upper panels, LVcmax) or RuBP regeneration (bottom panels, LJ) under the light condition of: A, 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 10, and 30 min; B, 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 60, and 30 min preceded by overnight darkness; or C, 2 h of sunlight followed by 5 h of darkness, then 0 and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10 and 50 min, respectively. The vertical bars on each symbol indicate the standard error with 3–6 replicate leaves for tobacco. Grey boxes in each figure represent the periods of darkness. The numbers (0 and 1,500) in the grey and white boxes at the top of (A), (B), and (C) indicate the light intensity.

Discussion

Photosynthetic induction has been investigated in relation to stomatal opening, activation of electron transport, or the enzymes of the Calvin–Benson cycle, especially Rubisco and sucrose synthesis (Stitt and Schreiber, 1988; Tanaka et al., 2019; Yamori et al., 2020). Although gm can impose a major limitation to A during the steady state, little is known about the dynamics of gm and its limitation of A under fluctuating light. In the present study, we aimed to characterize the dynamics of gm and the limitations to A imposed by gas diffusional and biochemical processes during photosynthetic induction to provide novel insight into the physiological mechanisms regulating carbon gain by plants under changing light conditions.

Light response of mesophyll conductance during steady and nonsteady states

The light response of gm under steady state is controversial since it varies between plant species and the method used to estimate gm. In tobacco, steady-state gm did not vary with light intensity when calculated from concurrent measurements of gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination (Yamori et al., 2010), but increased with increasing light intensity when calculated using the variable J method (Carriquí et al., 2019). In the present study, there was no clear variation in gm under steady state after changing from high (1,500 µmol m−2 s−1) to low (200 µmol m−2 s−1) light or low to high light in tobacco (Figure 5, A and C). This result confirms that gm estimated by concurrent measurements of gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination was similar under 200 and 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1 in tobacco.

The induction response of gm was observed after changing from overnight darkness to high or low light in Arabidopsis and tobacco in air containing 2% O2 (Figures 3, 5). Previously, Kaiser et al., (2017) reported the dynamics of gm using the variable J method, but the authors pointed out uncertainties associated with parameters relating to the estimation of electron transport rate (alternative electron transport, ATP and NADPH production, and leaf absorptance) and Rd after a step change in light. The evaluation of gm during photosynthetic induction would be affected by uncertainty in parameter values assumed for the calculation of gm (Gu and Sun, 2014) and by ignoring gcut when gs is low (Mizokami et al., 2015). In the present study, gm was rather insensitive to the assumed value of Rd in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Figure 1, B and D), indicating that small changes in Rd can be ignored in the evaluation of gm after a step change in light. The sensitivity of gm to changes in the four parameters, Rd, b, Ci, and Δo, was similar between the steady and nonsteady states. Varying each of these parameters by ±10% alters estimated gm values from -36.2% to 92.1% in both states (Figure 1, B and D). It should be noted that gm appears more variable during the early phase rather than the later phase of induction because Δo tended to be more uncertain owing to low A (Supplemental Figure S2 and Supplemental Data Set S1). Although variation in gcut caused a large variation in the estimation of gm initially when gs was very low, it resulted in only minor variation in the induction curves of gm in both plant species (Figure 2). This suggests that gcut would not be a major factor affecting the dynamics of gm. These results support the conclusion that the change observed in apparent gm during induction is unlikely to be attributable to measurement artifacts in the present study.

There was no significant variation in the induction speed of gm between the light transitions from darkness to low (200 µmol m−2 s−1) or high light (1,500 µmol m−2 s−1) in tobacco (Figure 5E). This observation suggests that gm has a similar speed of response regardless of light intensity. Following a 10 min dark interruption, gm reached a high value immediately after switching on the light (Figure 6A). Moreover, t50 and t90 values for gm were shorter under high light after a 60 min dark interruption following high light than after a 5 h dark interruption (Figure 7A). These results suggest that once gm is induced, gm recovers more quickly following a short interrupting period of darkness.

What is the physiological mechanism underlying the induction response of gm after a step change in light? It was shown that gm is closely related to the surface area of chloroplasts exposed to intercellular airspaces per unit leaf area (Sc; Evans et al., 1994). The thickness of the mesophyll cell wall is known to contribute significant resistance to internal CO2 diffusion (Terashima et al., 2011; Peguero-Pina et al., 2012). A simulation analysis indicated that the light response of gm would be affected by the three-dimensional structure of a leaf in which there are cells with different characteristics and light penetration is spatially variable (Théroux-Rancourt and Gilbert, 2017). In addition, the CO2 permeability of the plasma membrane and chloroplast envelope are major components of the internal resistance (Evans et al., 2009). Carriquí et al. (2019) reported in tobacco that while gm varied under different light intensities, morphological factors did not, concluding that the response of gm to light was likely due to changes in biochemical factors such as the activity of aquaporins and carbonic anhydrase. It should be noted that Carriquí et al. (2019) investigated variation in morphological factors and gm under different light intensities after adaptation to high light (1,500 µmol photons m−2 s−1) in which the morphological arrangement might be fully induced. Thus, in the present study, the induction response of gm after changing from darkness to low or high light could be attributable to changes in biochemical and/or morphological factors.

The chloroplast avoidance response induced by blue-light irradiation decreased Sc and then gm in Arabidopsis (Tholen et al., 2008), which may possibly suppress the induction of gm under high light after darkness. However, the rapid reduction of gm by blue-light irradiation that was completed within 2–3 min was insensitive to the addition of cytochalasin (Loreto et al., 2009), suggesting chloroplast movement probably does not contribute to the dynamics of gm following a step change in light. It has been shown that aquaporins function to regulate gm by affecting the CO2 permeability of the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis (Heckwolf et al., 2011; Uehlein et al., 2012), tobacco (Flexas et al., 2006; Uehlein et al., 2008), and rice (Hanba et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2019), respectively. Changes in membrane permeability associated with aquaporins are regulated by phosphorylation, heteromerization of isoforms, Ca2+ and proton concentrations, pressure, osmotic solute concentration, internal or external factors such as nutrient, temperature and reactive oxygen species, and subcellular trafficking (Chaumont et al., 2005), which might be associated with the regulation of the gm dynamics.

Gas diffusional and biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction

According to the biochemical model for C3 photosynthesis, A is limited by RuBP carboxylation, RuBP regeneration, or triose phosphate utilization (TPU, starch, and sucrose synthesis), depending upon CO2 and O2 partial pressures, light intensity, and temperature (Farquhar et al., 1980, Sharkey, 1985). A few studies have evaluated the responses of Vcmax and J during induction under ambient CO2 and O2 conditions based on dynamic A–Ci analysis. The responses of A to Ci were generated by varying ambient CO2 concentrations at different times during photosynthetic induction (Soleh et al., 2016; Taylor and Long, 2017; Salter et al., 2019; De Souza et al., 2019; Acevedo-siaca et al., 2020). These previous studies evaluated the stomatal and nonstomatal limitations during induction (Soleh, et al., 2016; Taylor and Long, 2017; Deans et al., 2019), and reported the primary limitation to A was imposed by either gs, Vcmax, or J, depending on the plant species or the measurement conditions. However, Vcmax and J estimated by a dynamic A–Ci analysis is not only affected by biochemical factors, but also by gm, meaning that the estimated limitations depend on what happens to gm. Under 21% O2, one could expect a lag between the oxygenase reaction by Rubisco and the release of CO2 from photorespiration. This lag could vary during photosynthetic induction and is evident as a CO2 burst in darkness following a period in the light (Vines et al., 1983). The lag could result in the overestimation of Vcmax. In the present study, we evaluated the induction response of Vcmax and J under 2% O2 condition knowing the dynamic changes in gm, and assumed A was under RuBP-carboxylation or RuBP-regeneration limiting conditions (Figures 3, 6). As photorespiration is virtually eliminated under 2% O2, photorespiration is unlikely to have influenced our estimation of Vcmax during induction. The induction response of Vcmax that we observed after changing from darkness to high light in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Figure 3) is similar to that reported for several plant species, while the response of J was much slower in the present study than that shown in Taylor and Long (2017). Notably, the present study revealed substantial limitations to A by gs, gm, and Vcmax or J during photosynthetic induction (Figures 4, 8), indicating that speeding up both gas diffusional and biochemical processes could achieve faster photosynthetic induction in plants after a step change in light. In particular, gs responded more slowly than gm and Vcmax to changing light, which resulted in much greater Lgs than Lgm and LVcmax during photosynthetic induction assuming the RuBP-carboxylation limiting condition (Table 1, Figures 4, 8). On the other hand, LJ was much greater than Lgs and Lgm during the induction assuming the RuBP-regeneration limiting condition. Taken together, faster stomatal opening and activation of electron transport could improve carbon gain during photosynthetic induction following a transition from darkness to high light (Yamori, 2016; McAusland et al., 2016; Lawson and Vialet-Chabrand, 2019; Matthews et al., 2019; Papanatsiou et al., 2019; Kimura et al., 2020; Yamori et al., 2020).

TPU can limit A under steady-state conditions of high CO2 and/or low O2 (Sharkey, 1985). TPU can also limit A under non-steady-state conditions under ambient CO2 and O2 (Stitt and Schreiber, 1988). In the present study, gas exchange measurements were conducted in 2% O2 to minimize the effect of photorespiration on carbon isotope discrimination, which might increase the likelihood for TPU limitation of A during the photosynthetic induction compared to that under 21% O2. If so, the limitations imposed by Vcmax or J may have been overestimated during induction.

In the present study, the induction responses of gs and Vcmax were shown after changing from darkness for 10 min to high light (Figure 6A). This suggests that a short period of darkness (even 10 min) would result in stomatal closure and Rubisco inactivation, which would then again require photosynthetic induction upon re-illumination. In addition, a rapid change in RuBP regeneration was reported to limit photosynthetic induction under high light after a short period of low light or darkness (Kobza and Edwards, 1987; Sassenrath-Cole and Pearcy, 1992), which would also apply in the present study. Although LVcmax was much larger than Lgs and Lgm when RuBP-carboxylation limiting conditions were assumed, Vcmax rapidly reached steady state under high light after 10 min darkness, while gs and gm slowly increased (Figures 6, 8). On the other hand, LJ was more than 95% throughout induction, while gs and gm showed slower responses than J. Lgm was smallest of all the limitations during most of the induction phase regardless of which limiting conditions were assumed following a step change in light, suggesting that the induction of mesophyll conductance would not greatly affect A when light intensity varies. These results suggest that the induction speed of A under high light following a short period of darkness would be mainly limited by stomatal opening and/or electron transport.

Conclusion

We characterized the dynamics of mesophyll conductance (gm) after changing from darkness to high or low light in Arabidopsis and tobacco. The induction speed of gm was similar irrespective of the light intensity during photosynthetic induction. Once gm was fully induced, the response speed of gm was faster the shorter the period of darkness. During the induction of photosynthesis, CO2 assimilation rate (A) was mainly limited by stomatal conductance (gs), the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation (Vcmax), or electron transport (J), whereas the limitation associated with gm varied little and was less important. The most effective targets for increasing carbon gain by plants in dynamic light conditions are therefore likely to be faster stomatal opening and activation of electron transport.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and cultivation

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh, “Columbia-0 (CS60000)”) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. “Petit Havana (N,N)”) were used as plant materials in the present study. Arabidopsis plants were sown and grown on soil under an air temperature of 22°C and a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The day/night length was set to 8/16h. Tobacco plants were sown on April 16, 2019 and transplanted to 4L pots containing Green Wizard potting mix with slow release fertilizer (Osmocote Exact, Scotts, NSW, Australia) on May 3, 2019. Tobacco plants were grown under sunlight in a greenhouse with the day/night temperature of 25°C/20°C. All the plants were watered and fertilized as needed. Gas exchange measurements were made 53 and 54 d after sowing for Arabidopsis, and 45 to 52 d after sowing for tobacco plants.

Dynamic analysis of mesophyll conductance

The gas exchange and carbon isotope discrimination measurements were simultaneously conducted as described by Evans and von Caemmerer (2013). Prior to the measurement, plants were kept under dark conditions overnight or for 5 h after sunlight illumination for 2 h. In addition, the whole plant was kept under dark conditions during gas exchange measurements except for the leaves clamped into the chamber. We set a flow rate of 200 µmol s−1, a CO2 concentration of 400 µmol mol−1, 2% O2, and an air temperature at 24°C in the leaf chamber. The 2% O2 gas was supplied to LI-6400 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) as described by Evans and von Caemmerer (2013) to minimize the effect of photorespiration on the estimation of gm. Various light sequences were generated in the leaf chamber as follows; a PPFD of 0 and 1,000-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10 min and 50 min (LS1); 0, 1,500, and 200-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, and 20 min (LS2); 0, 200, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 40, and 30 min (LS3); 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 10, and 30 min (LS4); and 0, 1,500, 0, and 1,500-μmol photons m−2 s−1 for 10, 50, 60, and 30 min (LS5). The leaf to air vapor pressure difference decreased from 1.76 to 1.04 kPa in Arabidopsis and from 2.30 to 0.95 kPa in tobacco, respectively, during induction. The water content of air entering the chambers was set by flowing it through Nafion tubing (Perma Pure LLC, Toms River, NJ, USA, MH-110-12P-4) surrounded by water circulating from a temperature-controlled water bath. Gas exchange measurements were coupled to a tunable diode laser (TDL, TGA100, Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA) for measurement of the carbon isotope composition. The 12CO2 and 13CO2 composition of five gases were each measured for 20 s in a repeating 100 s cycle: CO2-zero gas, then reference and sample gases from two LI-6400s. Gas exchange measurements were made to obtain CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance to CO2 (gs), and CO2 concentration in intercellular airspaces (Ci) every 100 s with eight leaves of Arabidopsis under LS1, and four to six leaves of tobacco under LS2, LS3, LS4, LS5, and LS6. The carbon isotope discrimination, gm, and CO2 concentration in the chloroplast stroma (Cc) were calculated as described by Evans and von Caemmerer (2013) and Busch et al. (2020). gm was calculated by using the following equation

| (1) |

where t is the ternary correction factor (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012), b is the discrimination in the carboxylation reaction by Rubisco and PEPC (29‰), ai is the fractionation factor for dissolution and diffusion through water (1.8‰), e is the fractionation factor for day respiration, Rd is the day respiration, Δi, Δo, Δe, and Δf are the fractionations assuming Ci = Cc in the absence of any respiratory fractionation (e = 0), the observed fractionation, the fractionation associated with respiration, and the fractionation associated with photorespiration, respectively. For a more detailed explanation of Equation 1, see Evans and von Caemmerer (2013) and Busch et al. (2020). We measured the respiration rate during the initial dark period for each leaf and used leaf temperature response functions described by Bernacchi et al. (2001) to estimate Rd and the CO2 compensation point in the absence of Rd (Γ*). The linear relationship between Γ* and O2 partial pressure was assumed to estimate Γ* under 2% O2 (Brooks and Farquhar, 1985).

Sensitivity analysis in the estimation of mesophyll conductance

Sensitivity of the gm estimation to changes in Rd, Ci, b, and Δo was evaluated by changing these parameters from -10%, -5%, +5%, or +10% of the true values. Sensitivity analysis was conducted on the data collected at 10 and 40 min after the light intensity was changed from darkness to 1,000 or 1,500 µmol photons m−2 s−1 in Arabidopsis and tobacco, respectively, with the dataset shown in Figure 1, A and C. In addition, potential errors in Δo depending on the measurement stability of the TDL system were calculated from the following equation

| (2) |

where δ13Cref was the carbon isotope composition of the reference gases from two LI-6400s. ξ was defined as Cref/(Cref - Csam), in which Cref and Csam are the CO2 concentrations of reference and sample gases. Subsequently, the potential variation range of Δo was calculated as the ratio of errors in Δo to the actual value of Δo at each time point.

It was reported that Ci can be overestimated when gs is low if cuticular conductance to water vapor (gcut) is ignored. This could result in the underestimation of gm (Mizokami et al., 2015). In the present study, we simulated the variability in gm with the change in gcut. Ci is calculated from the following equation according to Boyer et al. (1997)

| (3) |

where gsc is the stomatal conductance to CO2, Es is the transpiration rate via stomata, and Ca is the CO2 concentration in the leaf chamber. gsc and Es are defined as the following equations

| (4) |

| (5) |

where glw is the total stomatal conductance to water vapor, El is the total transpiration rate, Wl and Wa are the mole fraction of water vapor in the leaf and the leaf chamber, respectively. Ci and gm were calculated by assuming gcut of 0, 1, 3, or 5 mmol m−2 s−1 in Arabidopsis and tobacco with the dataset shown in Figure 1, A and C.

Analysis of gas diffusional and biochemical limitations of the photosynthetic induction

According to the biochemical model of photosynthesis developed by Farquhar et al. (1980), A under RuBP-carboxylation (Ac) or RuBP-regeneration (Ar) limiting condition are described as below

| (6) |

| (7) |

where Vcmax is the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation, C and O are the CO2 and O2 concentration, and Kc and Ko are the Michaelis constants for CO2 and O2, respectively. J is the rate of whole chain linear electron transport. Based on equations (6) and (7), we calculated Vcmax and J using the following equations

| (8) |

| (9) |

Here, the observed A at each measurement was substituted for Ac and Ar under a PPFD of 1,000 µmol m−2 s−1 in Arabidopsis or 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1 in tobacco in Equations 6 and 7, respectively. Kc and Ko are calculated by using leaf temperature response functions described by Bernacchi et al. (2002). We evaluated the dynamics of Vcmax and J under each light condition assuming that A would be limited either by RuBP carboxylation or regeneration throughout the measurements in the present study.

The limitations to A imposed by the stomatal (Lgs) and mesophyll (Lgm) conductance, and Vcmax (LVcmax) or J (LJ) were examined using the following equations as described in Grassi and Magnani (2005)

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

where gtot was the total conductance to CO2 from the leaf surface to chloroplast stroma assuming gcut of 0 mmol m−2 s−1. ∂Ac/∂Cc and ∂Ar/∂Cc, the partial differential of Equations 6 and 7 to Cc, were calculated using the following equations

| (13) |

| (14) |

Curve fitting and statistical analysis

The plot sequences of four parameters, A, gs, gm, Vcmax, and J, were fitted to a Boltzmann sigmoidal function of time (f(t)) as described in Supplemental Figure S4

| (15) |

where Xmin and Xmax are the minimum and maximum values for each parameter, respectively, and t50 is the time when each parameter reached 50% of the maximum value after switching on the light, dt is (Xmax − Xmin)/(4 × slope at the inflection point) for each parameter. In the present study, gm, Vcmax, and J under the dark condition were assumed to be zero for the curve fitting since these parameters were unmeasurable under such conditions. The time when each parameter reached 90% of the maximum value (t90) was also calculated from the curve-fitted function. Curve-fitting was performed with the dataset under a PPFD of 1,500 µmol m−2 s−1 shown in Figures 3, 6, B and C, using curve fitting tool in the SciPy optimize module of Python (Python Software Foundation, Delaware, USA).

Unreasonable values of gm (i.e. gm ≥ 0.8 or gm ≤ 0) were eliminated prior to the calculation of its average value and the other parameters, and statistical analysis. Unreasonable values of Cc, Vcmax, and J (≤0) were also eliminated. The time series dataset of gas exchange parameters shown in Figure 3 is provided in Supplemental Data Set S1. It includes the average value of A, gs, gm, Ci, Cc, Vcmax, and J, and the replication number and standard deviation (column, “SD”) of those parameters at each timepoint.

We evaluated the significance of the variations in t50 and t90 among parameters or t50 and t90 of gm among light sequences according to the Tukey–Kramer test. The variation in gm under the steady state was compared between the light intensity of 200 and 1,500 µmol photons m−2 s−1 using a boxplot analysis. The values of gm in the last 10 min under 1,500 and 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1 in LS2 and LS3 were compared in a boxplot analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using R software version 3. 6. 1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Response of mesophyll conductance after changing from darkness to high light.

Supplemental Figure S2. Variations in parameters related to carbon isotope discrimination.

Supplemental Figure S3. Response of CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, and CO2 concentration in the intercellular airspaces and chloroplast stroma, following transitions to low and high light for tobacco.

Supplemental Figure S4. Example of curve-fitting time sequence data for gas exchange parameters through time.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Time series dataset of CO2 assimilation rate, stomatal and mesophyll conductance, CO2 concentration in the intercellular airspaces and chloroplast stroma, the maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation, and electron transport after changing from darkness to high light.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Soumi Bala and Aleu Mani George for expert technical assistance with plant culture and gas exchange measurements.

Funding

This work was supported by KAKENHI to W.Y. (Grant Numbers: 16H06552, 18H02185, 18KK0170, and 20H05687) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Research Fellow to K.S. from JSPS (20J00594), and the Center of Excellence for Translational Photosynthesis to J.R.E. (Grant Number: CE140100015) from the Australian Research Council.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

K.S., W.Y., and J.R.E. conceived and designed this work. K.S. performed all the gas exchange experiments and data analyses with the support by M.G. K.S. wrote the manuscript with input from co-authors and all the authors contributed extensively to its finalization.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article are in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys) are: K.S. (sakoda@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp), W.Y. (yamori@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

References

- Acevedo-siaca LG, Long SP, Coe R, Wang Y, Kromdijk J, Quick WP (2020) Variation in photosynthetic induction between rice accessions and its potential for improving productivity. New Phytol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Portis AR, Nakano H, von Caemmerer S, Long SP (2002) Temperature response of mesophyll conductance. Implications for the determination of Rubisco enzyme kinetics and for limitations to photosynthesis in vivo. Plant Physiol 130: 1992–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchi CJ, Singsaas EL, Pimentel C, Portis AR, Long SP (2001) Improved temperature response functions for models of Rubisco-limited photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 24: 253–259 [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD (1985) Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta 165: 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch FA, Holloway-Phillips M, Stuart-Williams H, Farquhar GD (2020) Revisiting carbon isotope discrimination in C3 plants shows respiration rules when photosynthesis is low. Nature Plants 6: 245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JS, Chin Wong S, Farquhar GD (1997) CO2 and water vapor exchange across leaf cuticle (epidermis) at various water potentials. Plant Physiol 114: 185–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR (2015) Temperature responses of mesophyll conductance differ greatly between species. Plant Cell Environ 38: 629–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campany CE, Tjoelker MG, von Caemmerer S, Duursma RA (2016) Coupled response of stomatal and mesophyll conductance to light enhances photosynthesis of shade leaves under sunflecks. Plant Cell Environ 39: 2762–2773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Silva AE, Salvucci ME (2013) The regulatory properties of rubisco activase differ among species and affect photosynthetic induction during light transitions. Plant Physiol 161: 1645–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriquí M, Douthe C, Molins A, Flexas J (2019) Leaf anatomy does not explain apparent short-term responses of mesophyll conductance to light and CO2 in tobacco. Physiol Plant 165: 604–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont F, Moshelion M, Daniels MJ (2005) Regulation of plant aquaporin activity. Biol Cell 97: 749–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans RM, Farquhar GD, Busch FA (2019) Estimating stomatal and biochemical limitations during photosynthetic induction. Plant Cell Environ 42: 3227–3240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethier GJ, Livingston NJ (2004) On the need to incorporate sensitivity to CO2 transfer conductance into the Farquhar-von Caemmerer-Berry leaf photosynthesis model. Plant Cell Environ 27: 137–153 [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S (2013) Temperature response of carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance in tobacco. Plant Cell Environ 36: 745–756 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02591.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Sharkey TD, Berry JA, Farquhar GD (1986) Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Aust J Plant Physiol 13: 281–292 [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Setchell BA, Hudson GS (1994) The relationship between CO2 transfer conductance and leaf anatomy in transgenic tobacco with a reduced content of Rubisco. Aust J Plant Physiol 21: 475–495 [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I (2009) Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2235–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Cammerer S, Berry JA (1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA (2012) Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant Cell Environ 35: 1221–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Hanson DT, Bota J, Otto B, Cifre J, McDowell N, Medrano H, Kaldenhoff R (2006) Tobacco aquaporin NtAQP1 is involved in mesophyll conductance to CO2 in vivo. Plant J 48: 427–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Scoffoni C, Gago J, Sack L (2013) Leaf mesophyll conductance and leaf hydraulic conductance: An introduction to their measurement and coordination. J Exp Bot 64: 3965–3981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Magnani F (2005) Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ 28: 834–849 [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Sun Y (2014) Artefactual responses of mesophyll conductance to CO2 and irradiance estimated with the variable J and online isotope discrimination methods. Plant Cell Environ 37: 1231–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba YT, Shibasaka M, Hayashi Y, Hayakawa T, Kasamo K, Terashima I, Katsuhara M (2004) Aquaporin facilitated CO2 permeation at the plasma membrane: over-expression of a barley aquaporin HvPIP2;1 enhanced internal CO2 conductance and CO2 assimilation in the leaves of the transgenic rice plant. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD (1992) Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiol 98: 1429–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckwolf M, Pater D, Hanson DT, Kaldenhoff R (2011) The Arabidopsis thaliana aquaporin AtPIP1;2 is a physiologically relevant CO2 transport facilitator. Plant J 67: 795–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Kromdijk J, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Marcelis LFM (2017) Photosynthetic induction and its diffusional, carboxylation and electron transport processes as affected by CO2 partial pressure, temperature, air humidity and blue irradiance. Ann Bot 119: 191–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E, Morales A, Harbinson J, Heuvelink E, Prinzenberg AE, Marcelis LFM (2016) Metabolic and diffusional limitations of photosynthesis in fluctuating irradiance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Rep 6: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H, Hashimoto-Sugimoto M, Iba K, Terashima I, Yamori W (2020) Improved stomatal opening enhances photosynthetic rate and biomass production in fluctuating light. J Exp Bot 71: 2339–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobza J, Edwards GE (1987) The photosynthetic induction response in wheat leaves: net CO2 uptake, enzyme activation, and leaf metabolites. Planta 171: 549–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T, Vialet-Chabrand S (2019) Speedy stomata, photosynthesis and plant water use efficiency. New Phytol 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Tsonev T, Centritto M (2009) The impact of blue light on leaf mesophyll conductance. J Exp Bot 60: 2283–2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JSA, Vialet-Chabrand S, Lawson T (2019) Role of blue and red light in stomatal dynamic behaviour. J Exp Bot 71: 2253–2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAusland L, Vialet-Chabrand S, Davey P, Baker NR, Brendel O, Lawson T (2016) Effects of kinetics of light-induced stomatal responses on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency. New Phytol 211: 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami Y, Noguchi K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Terashima I (2019) Effects of instantaneous and growth CO2 levels and abscisic acid on stomatal and mesophyll conductances. Plant Cell Environ 42: 1257–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami Y, Noguchi K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Terashima I (2015) Mesophyll conductance decreases in the wild type but not in an ABA-deficient mutant (aba1) of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia under drought conditions. Plant Cell Environ 38: 388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanatsiou M, Petersen J, Henderson L, Wang Y, Christie JM, Blatt MR (2019) Optogenetic manipulation of stomatal kinetics improves carbon assimilation, water use, and growth. Science 363: 1456–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW (1990) Sunflecks and photosynthesis in plant canopies. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 41: 421–453 [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Way DA (2012) Two decades of sunfleck research: looking back to move forward. Tree Physiol 32: 1059–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Flexas J, Galmés J, Niinemets Ü, Sancho-Knapik D, Barredo G, Villarroya D, Gil-Pelegrín E (2012) Leaf anatomical properties in relation to differences in mesophyll conductance to CO2 and photosynthesis in two related Mediterranean Abies species. Plant Cell Environ 35: 2121–2129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons TL, Flexas J, von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Genty B, Ribas-Carbo M, Brugnoli E (2009) Estimating mesophyll conductance to CO2: methodology, potential errors, and recommendations. J Exp Bot 60: 2217–2234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter WT, Merchant AM, Richards RA, Trethowan R, Buckley TN (2019) Rate of photosynthetic induction in fluctuating light varies widely among genotypes of wheat. J Exp Bot 70: 2787–2796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassenrath-Cole GF, Pearcy RW (1992) The role of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate regeneration in the induction requirement of photosynthetic CO2 exchange under transient light conditions. Plant Physiol 99: 227–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD (1985) Photosynthesis in intact leaves of C3 plants: Physics, physiology and rate limitations. Bot Rev 51: 53–105 [Google Scholar]

- Shimadzu S, Seo M, Terashima I, Yamori W (2019) Whole irradiated plant leaves showed faster photosynthetic induction than individually irradiated leaves via improved stomatal opening. Front Plant Sci 10: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha A, Buckley TN, Lockhart EL, Barbour MM (2019) The response of mesophyll conductance to short- and long-term environmental conditions in chickpea genotypes. AoB Plants 11: 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleh MA, Tanaka Y, Nomoto Y, Iwahashi Y, Nakashima K, Fukuda Y, Long SP, Shiraiwa T (2016) Factors underlying genotypic differences in the induction of photosynthesis in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Plant Cell Environ 39: 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza AP, Wang Y, Orr DJ, Carmo-Silva E, Long SP (2019) Photosynthesis across African cassava germplasm is limited by Rubisco and mesophyll conductance at steady state, but by stomatal conductance in fluctuating light. New Phytol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Schreiber U (1988) Interaction between sucrose synthesis and CO2 fixation III. Response of biphasic induction kinetics and oscillations to manipulation of the relation between electron transport, Calvin cycle, and sucrose synthesis. J Plant Physiol 133: 263–271 [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Adachi S, Yamori W (2019) Natural genetic variation of the photosynthetic induction response to fluctuating light environment. Curr Opin Plant Biol 49: 52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SH, Long SP (2017) Slow induction of photosynthesis on shade to sun transitions in wheat may cost at least 21% of productivity. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 372:20160543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Badger MR, Evans JR (2009) Light and CO2 do not affect the mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion in wheat leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2291–2301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR (2011) Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ 34: 580–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tholen D, Niinemets U (2011) Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 155: 108–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théroux-Rancourt G, Gilbert ME (2017) The light response of mesophyll conductance is controlled by structure across leaf profiles. Plant Cell Environ 40: 726–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Boom C, Noguchi K, Ueda S, Katase T, Terashima I (2008) The chloroplast avoidance response decreases internal conductance to CO2 diffusion in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1688–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R (2008) Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. Plant Cell 20: 648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Sperling H, Heckwolf M, Kaldenhoff R (2012) The Arabidopsis aquaporin PIP1;2 rules cellular CO2 uptake. Plant Cell Environ 35: 1077–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vines HM, Tu Z, Armitage AM, Chen S, Black CC (1983) Environmental responses of the post lower illumination CO2 burst as related to leaf photorespiration. Plant Physiol 73: 25–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Ariza LS, Kaines S, Badger MR, Cousins AB (2013) Temperature response of in vivo Rubisco kinetics and mesophyll conductance in Arabidopsis thaliana: comparisons to Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Environ 36: 2108–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR (2008) Soil water deficits decrease the internal conductance to CO2 transfer but atmospheric water deficits do not. J Exp Bot 59: 327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Douthe C, Flexas J (2018) Differential coordination of stomatal conductance, mesophyll conductance, and leaf hydraulic conductance in response to changing light across species. Plant Cell Environ 41: 436–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Liu X, Liu L, Douthe C, Li Y, Peng S, Huang J (2015) Rapid responses of mesophyll conductance to changes of CO2 concentration, temperature and irradiance are affected by N supplements in rice. Plant Cell Environ 38: 2541–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Wang K, Yuan W, Xu W, Liu S, Kronzucker HJ, Chen G, Miao R, Zhang M, Ding M, et al. (2019) Overexpression of rice aquaporin OsPIP1;2 improves yield by enhancing mesophyll CO2 conductance and phloem sucrose transport. J Exp Bot 70: 671–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi K, Hanba YT, Terashima I (2006) Effects of internal conductance on the temperature dependence of the photosynthetic rate in spinach leaves from contrasting growth temperatures. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1069–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Evans JR, von Caemmerer S (2010) Effects of growth and measurement light intensities on temperature dependence of CO2 assimilation rate in tobacco leaves. Plant Cell Environ 33: 332–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Masumoto C, Fukayama H, Makino A (2012) Rubisco activase is a key regulator of non-steady-state photosynthesis at any leaf temperature and, to a lesser extent, of steady-state photosynthesis at high temperature. Plant J 71: 871–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W (2016) Photosynthetic response to fluctuating environments and photoprotective strategies under abiotic stress. J Plant Res 129: 379–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Kusumi K, Iba K, Terashima I (2020) Increased stomatal conductance induces rapid changes to photosynthetic rate in response to naturally fluctuating light conditions in rice. Plant Cell Environ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.