Abstract

Background

Necuparanib, a rationally engineered low molecular weight heparin, combined with gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel showed an encouraging safety and oncologic signal in a phase Ib trial. This randomized multi-center phase II trial evaluates the addition of necuparanib or placebo to gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in untreated metastatic pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

Patients and Methods

Eligibility included 18 years, histologically or cytologically confirmed metastatic PDAC, measurable disease and ECOG performance status of 0–1. Patients were randomly assigned to necuparanib (5 mg/kg subcutaneous injection once daily) or placebo (subcutaneous injection once daily) and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel on days 1, 8, 15 of 28-day cycles. The primary endpoint was median overall survival and secondary endpoints included median progression-free survival, response rates and safety.

Results

One-hundred and ten patients were randomized, 62 to necuparanib arm and 58 to placebo arm. The futility boundary was crossed at a planned interim analysis and the study was terminated by the Data Safety Monitoring Board. The median overall survival was 10.71 months (95% Confidence interval [CI] 7.95, 11.96) for necuparanib arm and 9.99 months (95% CI 7.85, 12.85) for placebo arm (Hazard Ratio: 1.12, 95% CI 0.66, 1.89, p-value: 0.671). The necuparanib arm had a higher incidence of hematologic toxicity relative to placebo patients (83% and 70%).

Conclusion

The addition of necuparanib to standard of care treatment for advanced PDAC did not improve overall survival. Safety was acceptable. No further development of necuparanib is planned although targeting the coagulation cascade pathway remains relevant in PDAC. NCT01621243

Keywords: Necuparanib, low-molecular-weight heparin, metastatic pancreatic cancer, gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for 94% of all pancreas tumors[1]. Despite its relatively low incidence, PDAC is currently the fourth cause of cancer-related mortality and is projected to be number two by 2030 [2]. The high case-fatality ratio is attributable to the absence of proven screening approaches, non-specific and late clinical presentation and the poor response to conventional chemotherapy.

To date, conventional cytotoxic therapy is the standard for patients with metastatic PDAC. The current front-line treatments include either FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, irinotecan), or gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel. Both have been demonstrated to be associated with a statistically significant increase in overall survival and progression-free survival when compared to gemcitabine alone as first line therapy [3, 4].

Novel agents are urgently needed and current approaches typically involve combining novel therapeutics with either FOLFIRINOX or, more often, gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel [5]. One interesting approach to decrease the rate of tumor growth and disease spread involves the use of heparins. Heparins are glycosaminoglycans physiologically produced by mast cells and basophils. Heparins are widely known for their anticoagulant effect through their binding and increased activation of the inhibitory enzyme antithrombin III. [6]. Multiple lines of evidence have demonstrated that heparins and their pharmacokinetically improved versions, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), have anti-neoplastic functions that are independent from anti-coagulation effects [7–9]. Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that heparins have both anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic properties, resulting in decreased growth and metastatic potential of the tumor [10–14]. This category of drugs is potentially also involved in chemotherapy and immune modulation [15, 16]. Furthermore, LMWH down-regulates the expression of heparanase, causing a decreased degradation of heparan sulfate proteoglycan and consequently preventing metastatic spread of neoplastic cells [17].

One of the main drawbacks of using heparins is the risk of bleeding. Necuparanib (M402, Momenta) is a non-cytotoxic heparan sulfate mimetic engineered to have decreased anticoagulant activity and a retained ability to bind to key factors important in tumor growth and metastasis [21]. Preclinical data has demonstrated that necuparanib successfully interferes with various pathways involved in tumor progression via inhibition of angiogenesis, along with stromal and immune modulation [21].

A phase I, open-label, dose-finding study of necuparanib was conducted to evaluate the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and antitumor activity of necuparanib combined with gemcitabine or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in metastatic PDAC [22]. Data from the N= 39 patients enrolled in this phase I trial indicated that necuparanib was safe to administer at the recommended phase II dose (RP2D) of 5 mg/kg subcutaneously daily, when combined with gemcitabine or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in metastatic PDAC. An encouraging efficacy signal with a response rate of 38% and a median overall survival of 13.1 months was observed. Herein, we report the results of a randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel with necuparanib or placebo in untreated metastatic PDAC (NCT01621243).

Materials and Methods

Study design

This phase II trial was a placebo-controlled, double-blind study evaluating the antitumor activity of necuparanib or placebo combined with gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in untreated metastatic PDAC. The primary endpoint was median overall survival (OS). The trial was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at all participating sites and all participants provided informed consent.

Patients

Patients were eligible if they were at least 18 years of age, had histologically/cytologically confirmed PDAC, at least one site of disease measurable by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 and an Eastern Co-Operative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0– 1. Other key inclusion criteria included acceptable coagulation parameters (obtained ≤ 14 days prior to randomization) as demonstrated by prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time within ± 15% of normal limits. Exclusion criteria included: prior systemic therapy for metastatic PDAC or prior adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. Patients were also ineligible if they had recent coronary artery stenting, myocardial infarction in the past year or thrombosis requiring anticoagulation.

Treatment

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive necuparanib (5 mg/kg administered by subcutaneous injection once daily) or placebo (subcutaneous injection once daily) along with nab-paclitaxel (125 mg/m2 administered intravenously on days 1, 8 and 15 and gemcitabine (1000mg/m2 intravenous on days 1, 8 and 15), in cycles of 28 days, until progression of disease, intolerable toxicity or withdrawal of consent.

Study Objectives and Endpoints

The primary endpoint was median OS. Secondary endpoints included evaluation of progression free survival (PFS), response rate (RR), Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) response, pharmacokinetic evaluation and safety. Exploratory objectives included investigation of thromboembolic events and of the risk of developing heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with necuparanib compared to placebo.

Study Assessments

Baseline tumor assessment was performed within 28 days prior to randomization.

Efficacy for all patients was assessed by tumor assessment through Computerized Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of chest, abdomen and pelvis every 8 weeks (2 cycles) during therapy. Survival information as well as the incidence of thromboembolic events was collected for all patients until death or termination of the study.

Biostatistical Plan

The primary analysis population was an intention-to-treat population, defined as all the patients randomized and assigned to one of the treatment arms. Toxicity information was collected on all patients who received a dose of treatment. One-hundred and ten events (deaths) were required to obtain 80% power when assuming a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.5 for overall survival, with testing at a 10% significance level one-sided, and 1:1 randomization. Under the further assumptions of a median overall survival of 8.5 months for placebo and nab-Paclitaxel and gemcitabine versus 12.75 months for the necuparanib arm, together with a 12-month duration of accrual, 30 months of planned follow-up, 2% of patients lost to follow-up, and allowing for an interim futility assessment, a total of 114 events in N= 148 randomized patients, were required. OS and PFS were assessed for significance in the two treatment groups using the log-rank test and both were described using the Kaplan-Meier method to account for censored observations. One interim analysis solely for futility assessment was planned after 57 deaths (50% of target events) had occurred. If the z-value was less than −0.148, then the futility boundary would have been crossed and the trial would stop.

The study was overseen by an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). A planned interim analysis was performed on July 18th, 2016 where the DSMB concluded that futility was met as the z-score crossed the pre-established boundary of −0.148 (z-score=−0.42) and it was unlikely that a difference would be seen between the arms with continuation of the trial. No new safety signals were identified. Therefore, the study was unblinded and patients discontinued protocol therapy and the trial was terminated. The final data cut-off for data analysis was in July 2016. No further data were collected, and no further analyses were conducted after this date.

Results

Cohort Summary

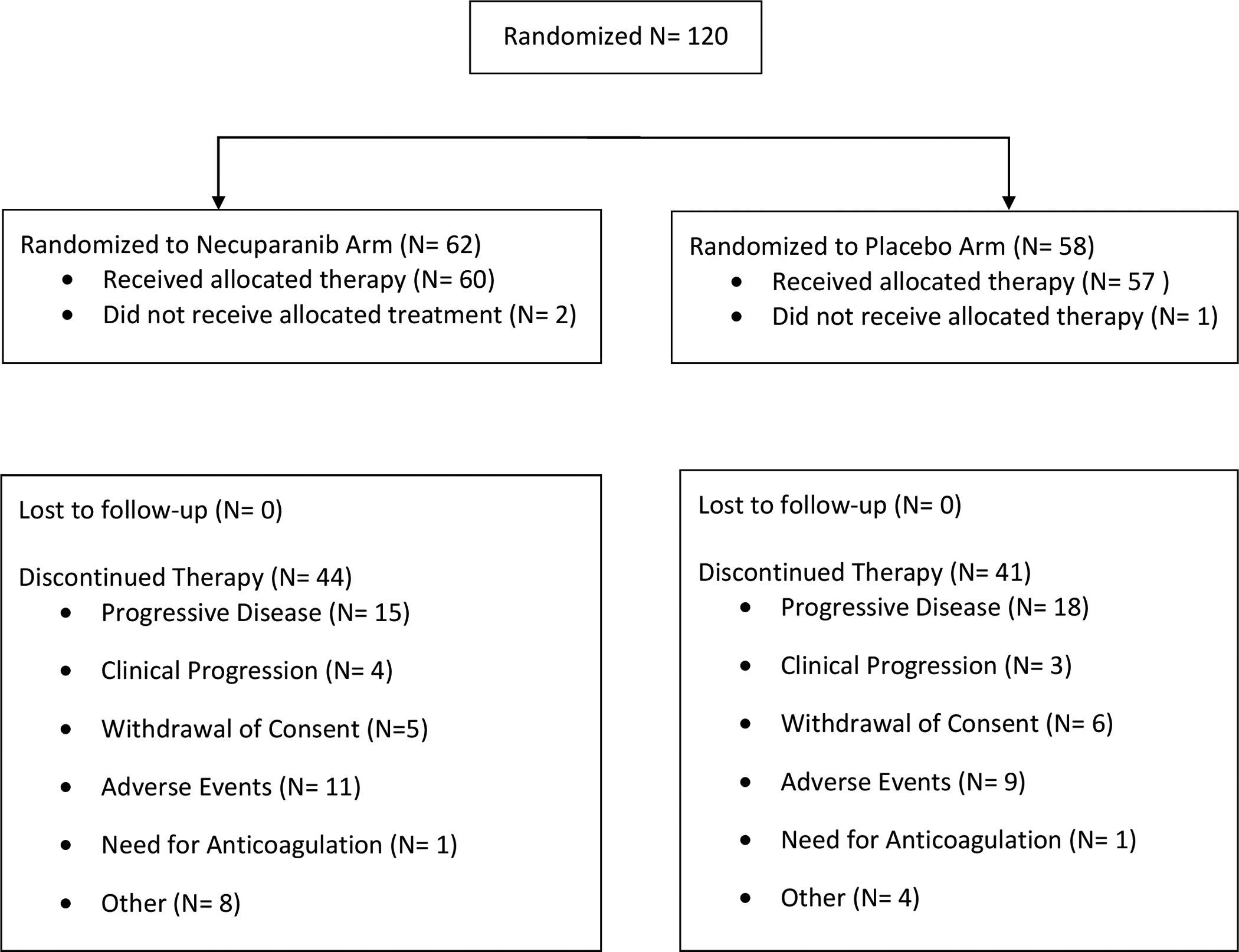

One hundred and twenty patients with metastatic PDAC were randomized to receive either gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel with necuparanib (N= 62) or gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel and placebo (N= 58). The median age for the entire cohort was 64 years. Forty-eight per cent were female and 87% were White. Baseline characteristics were evenly distributed in the two groups and are summarized in Table 1. One hundred and seventeen patients received therapy, corresponding to the safety population (60 necuparanib, 57 placebo). Patient disposition is summarized in the CONSORT diagram Figure 1.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics

| Necuparanib N=62 |

Placebo N=58 |

Total N=120 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number Randomized [n (%)] | 62 (100) | 58 (100) | 120 (100) |

| Number Treated [n (%)] | 60 (97) | 57 (98) | 117 (98) |

| Age | |||

| N | 62 | 58 | 120 |

| Median | 65.0 | 61.0 | 64.0 |

| Min, Max | 39, 81 | 43, 87 | 39, 87 |

| Sex [n (%)] | |||

| Female | 33 (53) | 25 (43) | 58 (48) |

| Male | 29 (47) | 33 (57) | 62 (52) |

| Race [n (%)] | |||

| Asian | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Black or African American | 3 (5) | 6 (10) | 9 (8) |

| White | 56 (90) | 48 (83) | 104 (87) |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (5) | 6 (10) | 9 (8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 58 (94) | 51 (88) | 109 (91) |

| Not Reported | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) |

| History of Smoking [n (%)] | |||

| Current | 5 (8) | 8 (14) | 13 (11) |

| Previous | 26 (42) | 30 (52) | 56 (47) |

| Never | 31 (50) | 19 (33) | 50 (42) |

| Alcohol Consumption [n (%)] | |||

| Current | 37 (60) | 25 (43) | 62 (52) |

| Previous | 6 (10) | 11 (19) | 17 (14) |

| Never | 19 (31) | 22 (38) | 41 (34) |

| Time since Initial Diagnosis (days) | |||

| N | 61 | 59 | 120 |

| Median | 18.0 | 18.0 | 18.0 |

Figure 1:

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Survival Outcomes and Tumor Response Rates

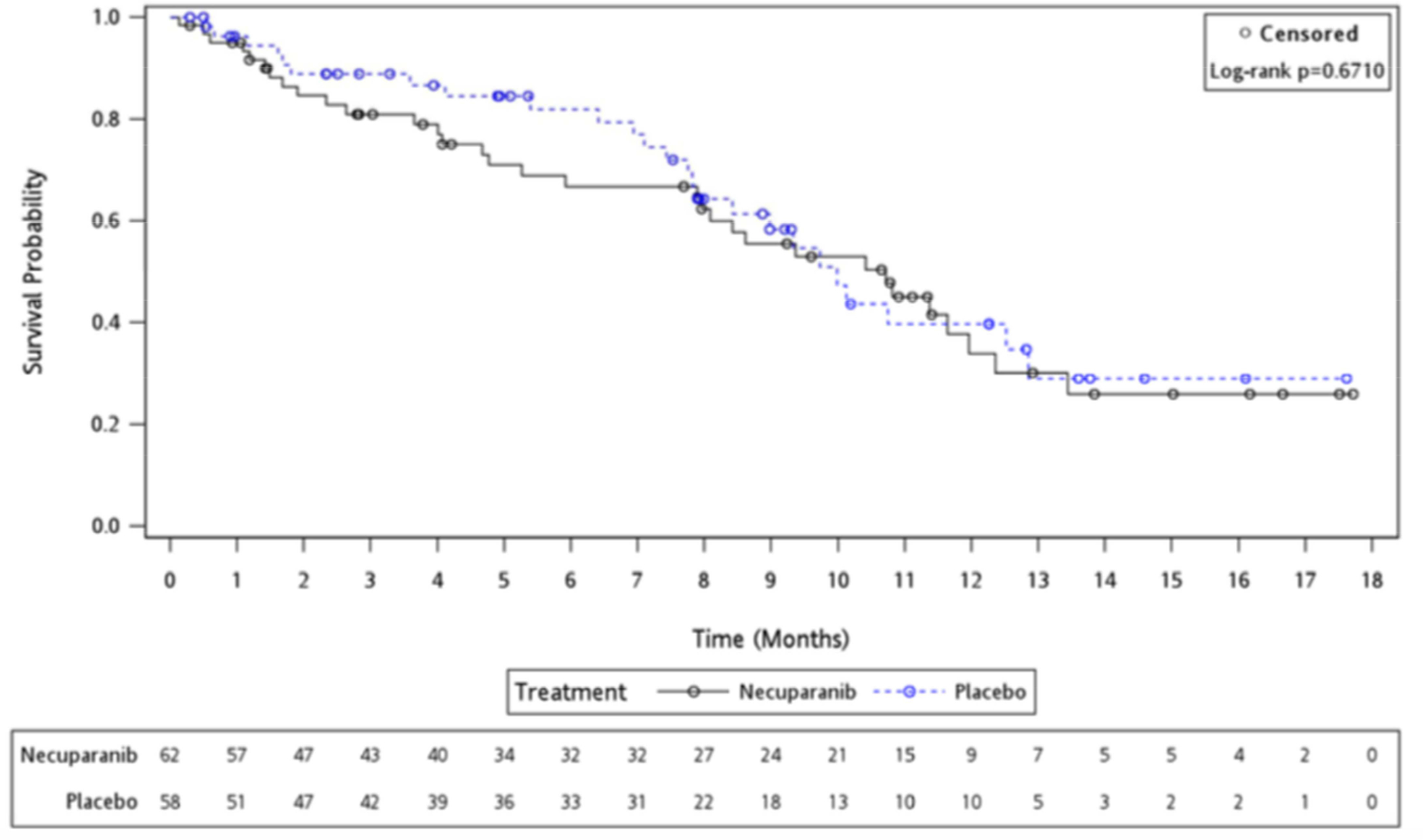

Results are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. For the primary endpoint median OS was 10.71 months (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 7.95 – 11.96 months) in the necuparanib arm and 9.99 months (95% CI 7.85 – 12.85 months) in the placebo arm (P= 0.671) and HR for survival for necuparanib over placebo was 1.12 (95% CI 0.66 – 1.89), in favor of the latter.

Table 2:

Efficacy Results

| Necuparanib N=62 |

Placebo N=58 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall Survival | ||

| Time to event (months) | ||

| Median | 10.71 | 9.99 |

| 95% CI for Median | 7.95, 11.96 | 7.85, 12.85 |

| Z-score for futility | −0.42 | |

| Hazard Ratio (Necuparanib Vs. Placebo) | 1.12 | |

| 95% CI | 0.66, 1.89 | |

| P-value (Necuparanib vs Placebo) | 0.671 | |

| 12-months Survival | ||

| Event Free Probability | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| 95% CI for Rate | 0.19, 0.49 | 0.23, 0.56 |

| Progression Free Survival | ||

| Time to event (months) | ||

| Median | 5.52 | 6.93 |

| 95% CI for Median | 3.65, 8.31 | 4.11, 7.75 |

| Hazard Ratio (Necuparanib Vs. Placebo) | 0.97 | |

| 95% CI | 0.61, 1.54 | |

| P-value (Necuparanib vs Placebo) | 0.886 | |

| Overall Response Rate | ||

| Best Response (confirmed) [n (%)] | ||

| Complete Response | - | 2 (3%) |

| Partial Response | 14 (23%) | 8 (14%) |

| Stable Response | 13 (21%) | 14 (24%) |

| Progressive Disease | 5 (8%) | 8 (14%) |

| Not Evaluable | 30 (48%) | 26 (45%) |

| Disease Control Rate (confirmed) (n [%]) | 27/62 (44%) | 24/58 (41%) |

| 95% exact CI or Objective Response rate | 0.310, 0.567 | 0.286, 0.551 |

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier Overall Survival Curve

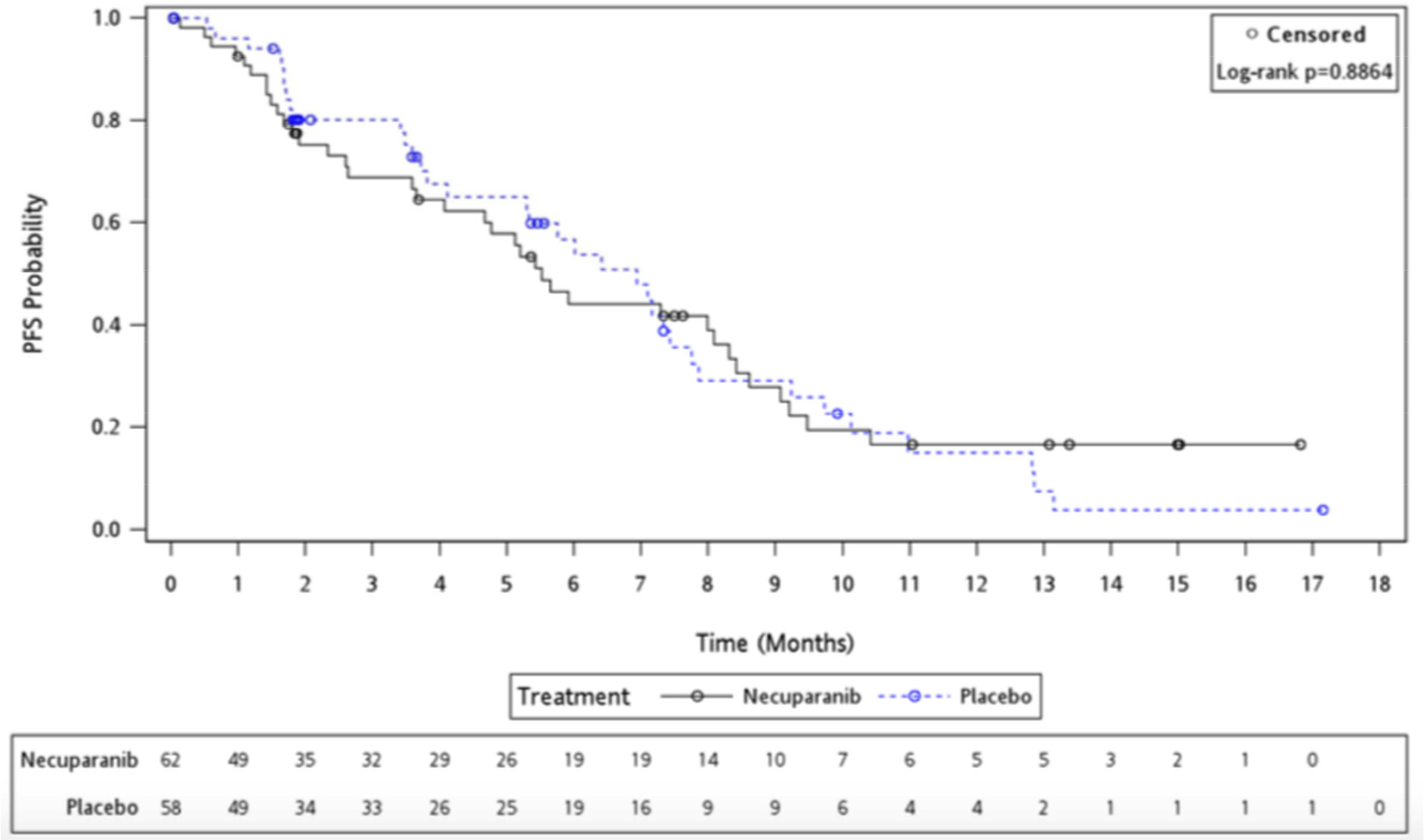

Median PFS was 5.52 months (95% CI 3.65 – 8.31) for the necuparanib arm and 6.93 months (95% CI 4.11 – 7.75) for placebo arm, with a HR of 0.97 (95% CI 0.61 – 1.54) (P= 0.886); Figure 3.

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier Progression-Free Survival Curve

There was no difference in RR between treatment arms. For the necuparanib arm: 14 (23%) patients had a partial response (PR), 13 (21%) had stable disease (SD), and 5 (8%) had disease progression (POD). For the placebo arm 2 (3%) patients had a complete response (CR), 8 (14%) had a PR, 14 (24%) had SD, and 8 (14%) had POD.

Safety

Safety data are summarized in Table 3. The Common Toxicity Criteria Adverse Event (CTCAE) version 4.03 was used. Treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE), irrespective of relationship, were observed in 58 (97%) patients in the necuparanib arm and 56 (98%) in the control arm. In the necuparanib arm, 48 (80%) patients had grade 3+ adverse events (AE), of whom 7 (12%) experienced grade 5 toxicity. In the placebo arm, 46 (81%) patients experienced grade 3+ toxicities, with 5 (9%) patients having grade 5 AE’s, primarily attributable to POD on study.

Table 3:

Summary of Safety Results

| Number of patients with at least one | Necuparanib N=60 |

Placebo N=57 |

Total N=117 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAE* | |||

| Any Grade | 58 (97%) | 56 (98%) | 114 (97%) |

| Grade 1 | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Grade 2 | 8 (13%) | 9 (16%) | 17 (15%) |

| Grade 3 | 30 (50%) | 30 (53%) | 60 (51%) |

| Grade 4 | 11 (18%) | 11 (19%) | 22 (19%) |

| Grade 5 | 7 (12%) | 5 (9%) | 12 (10%) |

| Related Grade 3+ TEAE | 21 (35%) | 9 (16%) | 30 (26%) |

| Serious Related Grade 3+ TEAE | 7 (12%) | 4 (7%) | 11 (9%) |

| Patients who died on study from TEAE related to Necuparib or Placebo | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

TEAE: Treatment Emergent Adverse Events (irrespective of causation)

The most common AE’s for (necuparanib versus placebo) were fatigue (36 [60%] vs 31 [54%]), thrombocytopenia (36 [60%] vs 17 [30%]), anemia (32 [53%] Vs 23 [40%]), nausea (32 [53%] vs 19 [33%]), diarrhea (30 [50%] vs 12 [21%]) and neutropenia (29 [48%] vs 24 [42%]). The most common grade 3 TEAE seen in a higher percentage in the necuparanib arm compared to the placebo arm were: thrombocytopenia (16 [27%] vs 3 [5%]), anemia (13 [22%] vs 6 [1%]), fatigue (8 [13%] vs 6 [11%]), increased liver function tests (elevated ALT in 7 [12%] vs 0 [0%]; elevated AST in 6 [10%] vs 1 [2%], diarrhea (7 [12%] vs 0 [0%]) and hyponatremia (5 [8%] vs 2 [4%]). Overall, necuparanib patients had a higher incidence, relative to placebo patients, of gastrointestinal disorders (85% vs 70%) and hematologic toxicity (83% vs 70%), including grade 3+ hematologic toxicity (65% vs 44%). Tables 4 and Table 5 summarize hematologic and non-hematologic toxicity, respectively.

Table 4:

Summary of Hematologic Toxicity and Events of Special Interest Related to Necuparanib

| Necuparanib N=60 |

Placebo N=57 |

Total N=117 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia | |||

| Any Grade | 36 (60%) | 17 (30%) | 53 (45%) |

| Grade 3 | 12 (20%) | 3 (5%) | 15 (13%) |

| Grade 4 | 4 (7%) | - | 4 (3%) |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Anemia | |||

| Any Grade | 32 (53%) | 23 (40%) | 55 (47%) |

| Grade 3 | 13 (22%) | 6 (11%) | 19 (16%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Neutropenia | |||

| Any Grade | 29 (48%) | 24 (42%) | 53 (45%) |

| Grade 3 | 17 (28%) | 14 (25%) | 31 (26%) |

| Grade 4 | 3 (5%) | 5 (9%) | 8 (7%) |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Lymphopenia | |||

| Any Grade | 8 (13%) | 6 (11%) | 14 (12%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Febrile Neutropenia | |||

| Any Grade | 3 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (3%) |

| Grade 5 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Necuparanib Related Toxicities | |||

| Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Catheter Site Hematoma | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Catheter Site Hemorrhage | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Device Related Thrombosis | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | _ | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Injection Site Hemorrhage | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Rectal Hemorrhage | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Hematochezia | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Skin Hemorrhage | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | - | - | - |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) Prolongation | |||

| Any Grade | 6 (10%) | 5 (9%) | 11 (9%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Epistaxis | |||

| Any Grade | 12 (20%) | 9 (16%) | 21 (18%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Pulmonary Embolism | |||

| Any Grade | - | 2 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 3 | - | 2 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Deep Vein Thrombosis | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (3%) |

| Grade 3 | - | 2 (4%) | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Superficial Vein Thrombosis | |||

| Any Grade | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

Table 5:

Summary of Non-Hematologic Toxicities

| Necuparanib N=60 |

Placebo N=57 |

Total N=117 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Disorders | |||

| Fatigue | |||

| Any Grade | 36 (60%) | 31 (54%) | 67 (57%) |

| Grade 3 | 8 (13%) | 6 (11%) | 14 (12%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal Disorders | |||

| Nausea | |||

| Any Grade | 32 (53%) | 19 (33%) | 51 (44%) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Diarrhea | |||

| Any Grade | 30 (50%) | 12 (21%) | 42 (36%) |

| Grade 3 | 7 (12%) | - | 7 (6%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Abdominal pain | |||

| Any Grade | 15 (25%) | 15 (26%) | 30 (26%) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (7%) | 9 (16%) | 13 (11%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | 1 (2%) | - |

| Metabolic Disorders | |||

| Hyponatremia | |||

| Any Grade | 13 (22%) | 7 (12%) | 20 (17%) |

| Grade 3 | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (5%) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Hypokalemia | |||

| Any Grade | 9 (15%) | 7 (12%) | 16 (14%) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (3%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Hypophosphatemia | |||

| Any Grade | 6 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (6%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Nervous System Disorders | |||

| Neuropathy Peripheral | |||

| Any Grade | 11 (18%) | 14 (25%) | 25 (21%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | |||

| Any Grade | 5 (8%) | 5 (9%) | 10 (9%) |

| Grade 3 | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (3%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Liver Function | |||

| AST Increase | |||

| Any Grade | 16 (27%) | 9 (16%) | 25 (21%) |

| Grade 3 | 6 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (6%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| ALT Increase | |||

| Any Grade | 21 (35%) | 7 (12%) | 28 (24%) |

| Grade 3 | 7 (12%) | - | 7 (6%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Infections | |||

| Pneumonia | |||

| Any Grade | 4 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (5%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 5 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Cardiopulmonary Disorders | |||

| Pericardial effusion | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 4 | 1 (2%) | - | 1 (1%) |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Edema Peripheral | |||

| Any Grade | 16 (27%) | 12 (21%) | 28 (24%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Pleural effusion | |||

| Any Grade | 4 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

| Hepatobiliary Disorders | |||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | |||

| Any Grade | 2 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 3 | 2 (3%) | - | 2 (2%) |

| Grade 4 | - | - | - |

| Grade 5 | - | - | - |

Treatment Discontinuation

Reasons for treatment discontinuation were balanced between arms except for progressive disease which occurred at a slightly lower frequency in the necuparanib arm in 19 (31%) patients versus 21 (36%) patients in placebo arm.

Antibody Response and Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT)

Twenty-three percent of necuparanib and 5% of placebo patients were IgG positive with an anti-heparin/PF4 antibody titer of ≥0.4 as measured at any timepoint during the study. Three patients had a positive serotonin release assay (SRA) result (a functional assay that measures heparin-dependent platelet activation). Of these three patients, one patient had a hemorrhagic stroke and two patients had no associated AEs (e.g., no thrombocytopenia or clinical events). Additional details are summarized in Table 4.

Subgroup Analyses

Univariate sensitivity analyses of efficacy (OS) were performed using each of the following as stratification factors: Ca 19-9, sex, age, ECOG, weight, prior surgery, number of cycles of therapy, hemoglobin level, platelets, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and number of metastatic sites. No differences in outcomes were observed between study arms.

Discussion

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is arguably the most lethal human malignancy. The high case-fatality rate and its increasing incidence underpin the need for new therapies. It is accepted that low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) has not only an anticoagulant role but also antineoplastic properties. Preclinical and clinical data have demonstrated an oncologic effect for patients taking LMWH with standard therapy [9–11, 15, 16]. An impact on survival from heparins is controversial and not definitively validated [18]. A retrospective analysis documented a modest survival advantage in patients with metastatic PDAC taking LMWH as an adjunct to standard chemotherapy when compared to those who did not receive LMWH (median survival 6.6 months [95% Confidence Interval CI, 5–8.2 months] for LMWH group and 3.8 months [95% CI, 2.5–5.1 months] for the non-LMWH group). However, the same benefit was not observed in patients who did not have metastatic disease [19]. A more recent multicenter, randomized, open-label trial investigated the effect on survival for the addition of LMWH to the best standard of care in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, hormone-refractory prostate cancer or locally advanced PDAC. A median survival of 13.1 months was observed in the low-molecular-weight heparin recipients compared to 11.9 months in the no-LMWH arm [20].

Given the conflicting results to date, the rationale for evaluating a novel therapeutic agent targeting this pathway is evident. The aim of the study reported herein was to assess whether the addition of necuparanib, an agent derived from unfractionated heparin and engineered for reduced anticoagulant activity, resulted in improved survival in chemo-naïve patients with metastatic PDAC when combined with standard therapy. Phase Ib evaluation determined that the addition of necuparanib to gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel was safe with a promising early efficacy signal [4, 22]. However, the addition of necuparanib to gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in this randomized phase II trial did not result in any improvement in overall survival and the study was stopped following a planned interim futility analysis. Grade 3+ thrombocytopenia and anemia were more commonly observed in the necuparanib arm relative to the placebo arm, as well as elevation of liver function enzymes and diarrhea. Overall, no new safety signals were obtained from this randomized phase II study.

The rationale for the use of necuparanib was compelling as a stromal/microenvironment modulator. Physiologically, glycosaminoglycans bind to cytokines and chemokines, resulting in an increased concentration which facilitates the interaction with their receptors [23]. Heparan sulfate mimetics act by altering angiogenesis, tumor-host cell trafficking, tumor cell mobility and tumor cell seeding. Notable binding targets are FGF2, VEGF and HGF, which are involved in the formation of new blood vessels [21, 24]. Another cytokine whose activity is modulated by necuparanib is SDF-1 [21]. This molecule acts primarily by recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells to the tumor site, which results in down-regulation of immune surveillance, thus facilitating tumor growth [25, 26]. Heparanase releases angiogenic factors, effectively promoting vascularization, endothelial cell migration and invasion [27]. Further, P-selectin expressed on activated endothelium contributes to cell extravasation and, when identified on activated platelets, induces the release of inflammatory agents [28]. Both the tumor-endothelium and tumor-platelet association increase the tumorigenic and progression potential [29].

The obvious question posed despite the compelling preclinical rationale is why the rationally engineered LMWH necuparanib was ineffective in patients with metastatic PDAC? A possible explanation could be that the RP2D, notwithstanding being associated with acceptable safety, was insufficient to overcome the barrier constituted by the tumor microenvironment. One can further hypothesize that the disease modifying effects of heparin sulfate mimetics seen in preclinical studies may not have the same influence in metastatic PDAC cells which may be resistant to the mechanisms exploited by necuparanib. It is also possible that the attenuation of the anti-coagulation effect of the drug may have led to loss of efficacy.

Limitations of this study include the early closure of the trial and no further outcome or safety data were collected following the DSMB recommendation for study termination.

To summarize, necuparanib combined with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel was generally safe however, there was no improvement in survival outcomes compared to standard therapy. Nonetheless, targeting the coagulation pathway remains of relevance in PDAC. These results provide a cautionary reminder regarding the need for prospective validation of promising signals seen in early trials conducted in select centers.

Highlights.

Preclinical data have demonstrated that necuparanib, a rationally engineered heparan sulfate mimetic with reduced anticoagulant effect, successfully decreased tumor growth and metastatic spread in relevant pancreas models.

Early phase Ib evaluation of gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel and necuparanib indicated safety for the combination and promising clinical activity.

A randomized phase II evaluation of gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel combined with necuparanib or placebo did not show a superior benefit for the addition of necuparanib and the study was terminated after a pre-planned interim analysis predicted futility for the experimental combination.

Acknowledgements

Paul Miller, Lou Vaikus

All patients and families

Research teams at all participating sites including the Academic and Community Research United (ACCRU)

Funding Sources

Momenta Pharmaceuticals

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant CA0008748

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presentation

Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium, San Francisco, California, January 20th, 2017.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosures/Competing Statements of Interest

EM O’R: Research funding to MSK: Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Roche, BMS, Celgene, MabVax Therapeutics, ActaBiologica, Parker Institute, AstraZenica, Silenseed. Consulting/Advisory: Cytomx, BioLineRx, Targovax, Celgene, Bayer, Loxo, Polaris.

DM: Research funding: Oncolytics and Merck. Consultant/Advisory: Amgen, Bayer, BMS, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelexis, Genentech

TBS: Consultant: Imugene, Immuneering, Bayer, Genentech, Incyte, Ipsen, Exelexis, Lilly, Astra-Zeneca, Merck and Array.

MR, JMR: Momenta Pharmaceuticals (former employee).

KTF: Board of Directors: Clovis Oncology, Strata Oncology, Vivid Biosciences, Checkmate Pharmaceuticals; Corporate Advisory Board: X4 Pharmaceuticals, PIC Therapeutics; Scientific Advisory Board: Sanofi, Amgen, Asana, Adaptimmune, Fount, Aeglea, Shattuck Labs, Tolero, Apricity, Oncoceutics, Fog Pharma, Neon, Tvardi, xCures, Monopteros, Vibliome; Consultant: Novartis, Genentech, BMS, Merck, Takeda, Verastem, Boston Biomedical, Pierre Fabre, Debiopharm.

DR: Equity: MPM Capital, Acworth Pharmaceuticals. Advisory Board: MPM Capital, Oncorus, Gritstone Oncology, Maverick Therapeutics. Publishing: Johns Hopkins University Press, Uptodate McGraw Hill.

All other authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018.

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014; 74(11):2913–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 2011; 364(19):1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med 2013; 369(18):1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiaravalli M, Reni M, O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: State-of-the-art 2017 and new therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treat. Rev 2017; 60:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee AYY, Levine MN, Baker RI et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 2003; 349(2):146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bochenek J, Püsküllüoğlu M, Krzemieniecki K. The antineoplastic effect of low-molecular-weight heparins – a literature review. Contemp. Oncol 2013; 17(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zacharski LR, Ornstein DL, Mamourian AC. Low-molecular-weight heparin and cancer. Semin. Thromb. Hemost 2000; 26 Suppl 1:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Low-molecular-weight heparins and cancer: focus on antitumoral effect. Ann. Med 2015; 47(2):116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balzarotti M, Fontana F, Marras C et al. In vitro study of low molecular weight heparin effect on cell growth and cell invasion in primary cell cultures of high-grade gliomas. Oncol. Res 2006; 16(5):245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu C-J, Ye S-J, Feng Z-H et al. Effect of Fraxiparine, a type of low molecular weight heparin, on the invasion and metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Oncol. Lett 2010; 1(4):755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abu Arab W, Kotb R, Sirois M, Rousseau E. Concentration- and time-dependent effects of enoxaparin on human adenocarcinomic epithelial cell line A549 proliferation in vitro. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 2011; 89(10):705–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norrby K Low-molecular-weight heparins and angiogenesis. APMIS 2006; 114(2):79–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debergh I, Van Damme N, Pattyn P et al. The low-molecular-weight heparin, nadroparin, inhibits tumour angiogenesis in a rodent dorsal skinfold chamber model. Br. J. Cancer 2010; 102(5):837–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niu Q, Wang W, Li Y et al. Low Molecular Weight Heparin Ablates Lung Cancer Cisplatin-Resistance by Inducing Proteasome-Mediated ABCG2 Protein Degradation. PLoS One 2012; 7(7):e41035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fluhr H, Seitz T, Zygmunt M. Heparins modulate the IFN-gamma-induced production of chemokines in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 2013; 137(1):109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasisekharan R, Shriver Z, Venkataraman G, Narayanasami U. Roles of heparan-sulphate glycosaminoglycans in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002; 2(7):521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang N, Lou W, Ji F et al. Low molecular weight heparin and cancer survival: clinical trials and experimental mechanisms. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 2016; 142(8):1807–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Delius S, Ayvaz M, Wagenpfeil S et al. Effect of low-molecular-weight heparin on survival in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Thromb. Haemost 2007; 98(2):434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Doormaal FF, Di Nisio M, Otten H-M et al. Randomized Trial of the Effect of the Low Molecular Weight Heparin Nadroparin on Survival in Patients With Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 2011; 29(15):2071–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou H, Roy S, Cochran E et al. M402, a Novel Heparan Sulfate Mimetic, Targets Multiple Pathways Implicated in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. PLoS One 2011; 6(6):e21106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Reilly EM, Roach J, Miller P et al. Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Antitumor Activity of Necuparanib Combined with Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: Phase I Results. Oncologist 2017; 22(12):1429–e139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoogewerf AJ, Kuschert GS, Proudfoot AE et al. Glycosaminoglycans mediate cell surface oligomerization of chemokines. Biochemistry 1997; 36(44):13570–13578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkman J, Klagsbrun M, Sasse J et al. A heparin-binding angiogenic protein--basic fibroblast growth factor--is stored within basement membrane. Am. J. Pathol 1988; 130(2):393–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamon M, Mbemba E, Charnaux N et al. A syndecan-4/CXCR4 complex expressed on human primary lymphocytes and macrophages and HeLa cell line binds the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1). Glycobiology 2004; 14(4):311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Linking Inflammation and Cancer. J. Immunol 2009; 182(8):4499–4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ilan N, Elkin M, Vlodavsky I. Regulation, function and clinical significance of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2006; 38(12):2018–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borsig L, Wong R, Feramisco J et al. Heparin and cancer revisited: Mechanistic connections involving platelets, P-selectin, carcinoma mucins, and tumor metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2001; 98(6):3352–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka NG, Tohgo A, Ogawa H. Platelet-aggregating activities of metastasizing tumor cells. V. In situ roles of platelets in hematogenous metastases. Invasion Metastasis 1986; 6(4):209–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Reilly EM, Mahalingam D, Roach JM et al. Necuparanib combined with nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: Phase 2 results. J. Clin. Oncol 2017; 35(4_suppl):370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]