Abstract

Legume plants form nitrogen (N)-fixing symbiotic nodules when mineral N is limiting in soils. As N fixation is energetically costly compared to mineral N acquisition, these N sources, and in particular nitrate, inhibit nodule formation and N fixation. Here, in the model legume Medicago truncatula, we characterized a CLAVATA3-like (CLE) signaling peptide, MtCLE35, the expression of which is upregulated locally by high-N environments and relies on the Nodule Inception-Like Protein (NLP) MtNLP1. MtCLE35 inhibits nodule formation by affecting rhizobial infections, depending on the Super Numeric Nodules (MtSUNN) receptor. In addition, high N or the ectopic expression of MtCLE35 represses the expression and accumulation of the miR2111 shoot-to-root systemic effector, thus inhibiting its positive effect on nodulation. Conversely, ectopic expression of miR2111 or downregulation of MtCLE35 by RNA interference increased miR2111 accumulation independently of the N environment, and thus partially bypasses the nodulation inhibitory action of nitrate. Overall, these results demonstrate that the MtNLP1-dependent, N-induced MtCLE35 signaling peptide acts through the MtSUNN receptor and the miR2111 systemic effector to inhibit nodulation.

Expression of a Medicago truncatula signaling peptide is upregulated by nitrate and inhibits nodulation through repression of the accumulation of a microRNA.

Introduction

Under nitrogen (N)-limited conditions, legume plants interact with rhizobia to form symbiotic root nodules, in which symbiotic bacteria fix atmospheric N that is then assimilated by the plant (Roy et al., 2020). Nodulation initiates following the relative recognition of the two compatible symbionts through the secretion of specific plant flavonoids in root exudates and of bacterial Nod Factor (NF) signals. This molecular dialogue triggers the infection of root hairs by rhizobia, which progress into infection threads toward inner root cell layers. Simultaneously, nodule organogenesis is initiated by the activation of cell divisions, which in the model legume Medicago truncatula occur mostly in inner cortical and pericycle cell layers (Xiao et al., 2014). The nodule primordium formed is later reached by growing infection threads, and then differentiates into a root nodule providing optimal conditions for symbiotic N fixation and assimilation. The energetic costs of nodule organogenesis, the metabolic support of the numerous rhizobia, and the carbon skeleton provision needed to support ammonium assimilation are all accomplished by the host legume plant, and thus the host plant tightly controls the number of nodules formed as well as N fixation activity per se (Suzaki et al., 2015).

One of the regulatory pathways that restrict the number of nodules formed on the root system is the long-distance (or systemic) “autoregulation of nodulation” (AON) pathway (Caetano-Anolles and Gresshoff, 1991). Initial rhizobial infection events activate a transcriptional reprogramming of root cells, and among those induced genes, several encode specific CLAVATA3/Embryo Surrounding Region (CLE) peptides, named MtCLE12 and MtCLE13 in M. truncatula (Mortier et al., 2010), LjCLE-root signaling (RS) 1, LjCLE-RS2, and LjCLE-RS3 in Lotus japonicus (Okamoto et al., 2009; Nishida et al., 2016), and Rhizobia-induced CLE 1 (RIC1) and RIC2 in soybean (Glycine max) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris; Lim et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2011; Hastwell et al., 2017). These CLE signaling peptides are matured from a precursor protein, secreted, and act noncell—autonomously in different developmental contexts (Hirakawa and Sawa, 2019; Fletcher, 2020). In Arabidopsis thaliana, their function is mostly associated with local regulations of cell proliferation and differentiation in meristems, requiring a short-distance movement of CLE peptides a few cell layers away, whereas in legumes, CLE peptides associated with the negative systemic regulation of nodulation induced by rhizobia (AON) or nitrate exhibit a long-distance movement from roots to shoots through the xylem vasculature. These CLE signaling peptides are then perceived by CLAVATA1-like Leucine-Rich Repeats Receptor-Like Kinases, which in the case of the negative regulation of nodule number are shoot-acting and named Super Numeric Nodules (SUNN) in M. truncatula, Hypernodulation and Aberrant Root Formation1 (HAR1) in L. japonicus, and Nodule Autoregulation Receptor Kinase (NARK) in soybean (Krusell et al., 2002; Searle et al., 2003; Schnabel et al., 2005). Downstream of the CLE peptide activation of these receptors in shoots, shoot-to-root systemic effectors are produced, which notably includes in L. japonicus and M. truncatula the downregulation of a specific mobile microRNA, miR2111, which reduces in roots the accumulation of Too Much Love gene transcripts (LjTML; and two homologous genes in M. truncatula, MtTML1 and 2: Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2020). TML genes encode Kelch-repeat F-box proteins that negatively regulate in roots the number of nodules downstream of the LjCLE-RS/LjHAR1 or of the MtCLE13/MtSUNN pathway (Magori et al., 2009; Takahara et al., 2013; Gautrat et al., 2019). These F-box proteins most probably target for ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis still unknown nuclear proteins critical for early nodulation, likely leading to the downregulation of genes involved in NF signaling and thus of rhizobial infections (Mortier et al., 2010; Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2019). Overall, the rhizobium-induced CLE/SUNN-HAR1/miR2111/TML pathway ensures a homeostatic inhibition of rhizobial infections and of the NF signaling pathway to optimize the number of nodules formed depending on environmental conditions and plant needs (Mortier et al., 2010; Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2019; Gautrat et al., 2020).

Legume CLE genes are indeed upregulated following rhizobial infections as well as by high-N conditions that are repressive for nodulation and N fixation (Suzaki et al., 2015). This includes the L. japonicus CLE-RS2, CLE-RS3, and CLE40 genes as well as the Nitrate-Induced CLE1 (NIC1) and NIC2 genes in soybean (Okamoto et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2011; Nishida et al., 2016). More recently, Nodule Inception (NIN)-Like Protein (NLP) transcription factors were shown to participate in the nitrate inhibition of nodulation (NON), with LjNLP4, also referred to as Nitrate unResponsive SYMbiosis 1 (NRSYM1), binding to the LjCLE-RS2 promoter and triggering its upregulation by nitrate (Nishida et al., 2018). Additionally, in M. truncatula, an NLP acts in roots to mediate the NON, MtNLP1, but no link with the nitrate-induced MtCLE/MtSUNN systemic inhibition of nodulation has been established (Lin et al., 2018).

Indeed, no CLE gene upregulated by nitrate has yet been identified in M. truncatula, in contrast to L. japonicus and soybean. Recent phylogenetic and clustering studies, however, revealed uncharacterized MtCLE genes closely related to the nitrate-regulated LjCLE-RS2 and NIC genes, namely MtCLE34 and MtCLE35 (Goad et al., 2017; Hastwell et al., 2017). However, MtCLE34 contains a mutation generating a premature stop codon, suggesting that it is not functional (Hastwell et al., 2017). In this study, we demonstrate that MtCLE35 expression is locally upregulated by high-N conditions, which depends at least on MtNLP1, and in turn negatively regulates nodule number depending on the MtSUNN receptor, indicating that this nitrate-inhibitory pathway regulating nodulation is conserved between legumes. We also show that a high N provision, or the ectopic expression of MtCLE35, represses the systemic accumulation of miR2111, and thus enhances MtTML1 and MtTML2 transcript accumulation, in agreement with the repressive effect on nodulation of these environmental conditions and signaling peptide. Finally, we show that the ectopic expression of miR2111, or the downregulation of MtCLE35 expression by RNA interference (RNAi), allows a partial bypass of the NON. Overall, we show that, in parallel to the now well-described rhizobium-induced AON pathway involving MtNIN/MtCLE12–MtCLE13/MtSUNN/MtmiR2111/MtTML1–MtTML2 in M. truncatula (Mortier et al., 2010; Gautrat et al., 2020), a very similar N-induced negative systemic pathway exists, involving MtNLP1/MtCLE35/MtSUNN/MtmiR2111/MtTML1–MtTML2.

Results

The upregulation of MtCLE35 expression by N relies on MtNLP1

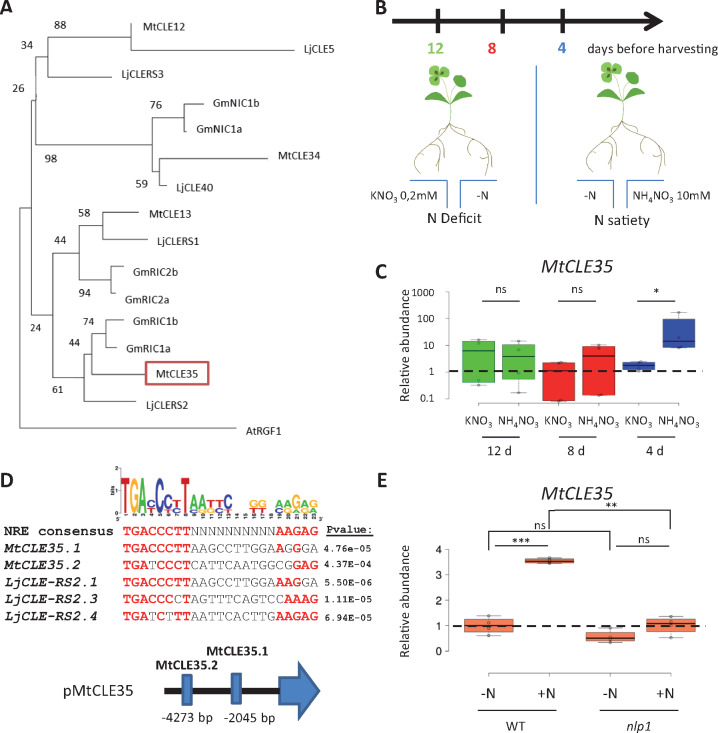

To identify a CLE peptide-encoding gene with expression induced by nitrate, we generated a phylogenetic tree focused on those CLE precursors from different legumes and already known to be related to AON (Figure 1A), revealing two previously non-characterized M. truncatula CLE peptide-encoding genes named MtCLE34 and MtCLE35. These genes are, respectively, closely related to the soybean NIC genes and the L. japonicus CLE40 gene, or to the soybean RIC1 genes and the L. japonicus CLE-RS2 gene (Reid et al., 2011; Nishida et al., 2016). To determine if the expression of these MtCLE genes was indeed upregulated by N, and if this was subject to local and/or systemic regulation, a split-root experiment was performed, designed based on previous knowledge gained on M. truncatula N responses (Figure 1B; Ruffel et al., 2008). Half of the root system of plants was thus placed in a low-N environment, namely KNO3 0.2 mM, previously shown to lead to a plant N deficit, whereas other plants were grown in a high-N environment, namely NH4NO3 10 mM, allowing plants to rapidly experience N satiety. In both cases, the other half of the root system was placed in a medium without N. This revealed that over the 4, 8, and 12 d N treatment kinetic, only MtCLE35 expression was locally induced at 4 d after the N treatment, independently of the KNO3 or NH4NO3 source used (Figure 1C), whereas MtCLE34 was not significantly regulated (Supplemental Figure S1). The CLE precursor protein encoded by MtCLE34 is mutated, and thus predicted not to generate a CLE signaling peptide, suggesting pseudogenization (Hastwell et al., 2017). Together with these expression data, this suggests that the locally N-upregulated MtCLE35 gene is the likely M. truncatula functional homolog of LjCLE-RS2 in L. japonicus. Using a similar split-root experimental set-up, but with a heterogeneous inoculation with rhizobium, MtCLE35 was additionally shown to be locally upregulated by rhizobium (Supplemental Figure S2), similar to LjCLE-RS2.

Figure 1.

MtCLE35 expression is upregulated by high N depending on MtNLP1. A, Similarity tree of CLE pre-propeptide sequences from M. truncatula, L. japonicus, and G. max, selected based on their similarity with MtCLE35, and including AtRGF1 as an outgroup. 1,000 bootstraps were performed, and confidence values (in percentage) are indicated. B, Experimental design of the split-root experiment, where treatments were applied during 4, 8, or 12 d and plants of the same age were collected. Split-root experiments were performed using two different local treatments, one to generate plant N deficit (KNO3 0.2 mM) and the other to generate plant N satiety (NH4NO3 10 mM). Systemic responses to N deficit or N satiety were analyzed in distant roots grown on a medium without N (−N) in both cases. C, Analysis of MtCLE35 expression by RT-qPCR in roots of WT plants grown in the split-root experimental system described in (B). To highlight local regulations, ratio between N-treated and non-treated (distant) roots is shown. Center lines show the medians of two biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between local N treatments (∗P < 0.05; ns, not significant). D, Putative MtNLP1 binding cis-elements in the promoter of MtCLE35. NRE cis-elements were identified in 5-kb promoters of LjCLE-RS2 and MtCLE35 using the consensus defined in L. japonicus by Nishida et al. (2018) and the FIMO software, and associated P-values are indicated on the right of each NRE identified. These NRE sequences were then aligned to generate a logo motif using Weblogo, and letters in bold red are identical to the LjNRE consensus. Below the alignment is a schematic representation of the MtCLE35 promoter indicating the two putative cis-elements. E, MtCLE35 gene expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR in roots of WT and nlp1 mutants grown with (+N) or without (−N) KNO3 10 mM. Center lines show the medians of two biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Data were normalized to 1 relatively to the WT control grown without N (−N), as indicated with dotted lines. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

LjCLE-RS2 upregulation by N relies on NLP transcription factors, so we thus searched for an NLP binding site motif, termed as NRE for “Nitrate Responsive Element” in L. japonicus (Nishida et al., 2018), in a 5-kb region upstream of the MtCLE35 open reading frame (Figure 1D;Supplemental Figure S3A). Using the Find Individual Motif Occurrences (FIMO) software (http://meme-suite.org/index.html), two regions of the MtCLE35 promoter, located 2,045 and 4,273 nucleotides upstream of the ATG, were identified as showing significant similarity with NRE cis-elements previously characterized in the LjCLE-RS2 promoter. This suggested that the upregulation of MtCLE35 by N could be mediated by NLP transcription factors as demonstrated in L. japonicus. A role for MtNLP1 in N inhibition of nodulation was recently characterized in M. truncatula (Lin et al., 2018), and the corresponding mutant allowed to test if the induction of MtCLE35 expression by N was altered (Figure 1E). Indeed, N induction of MtCLE35 expression was reduced in the nlp1 mutant compared to the wild-type (WT). Overall, this indicates that N upregulation of the AON-related MtCLE35 gene relies on the MtNLP1 transcription factor.

MtCLE35 negatively regulates nodule number depending on the MtSUNN receptor

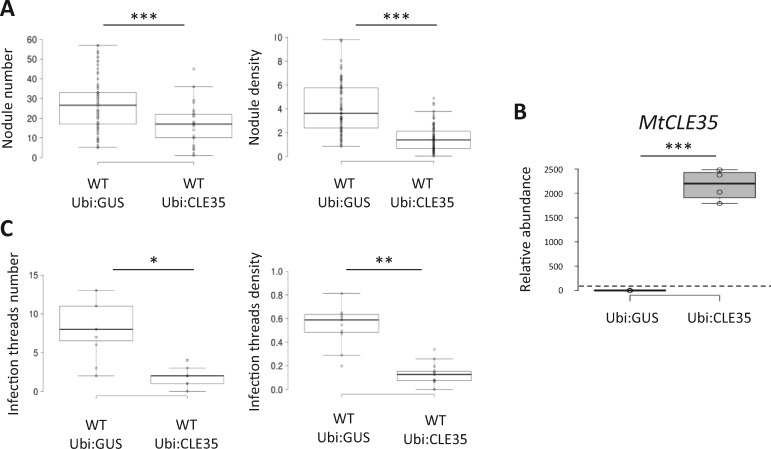

To determine if MtCLE35 regulates nodulation, and if so, in relation or not to the AON pathway, an overexpressing strategy was used in WT versus sunn mutant plants. In the WT, a significant decrease of the nodule number was observed in Ubi:CLE35 roots (Figure 2A, left panel). Moreover, a significant decrease in the nodule density (nodule number normalized to the root dry weight; Figure 2A, right panel) was also observed, indicating that the observed nodulation phenotype was independent of root growth. As expected, a high expression of the MtCLE35 transgene was detected in Ubi:CLE35 roots compared to Ubi:GUS control roots (Figure 2B). The rhizobium infection phenotype was then analyzed using a bacterial strain expressing a LacZ marker, revealing a reduction of the infection thread number and density (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

MtCLE35 ectopic expression inhibits nodulation and rhizobial infections. A, Nodule number (left panel) and density (nodules/mg of root dry weight; right panel) of WT roots transformed with a Ubi:GUS control construct or a Ubi:MtCLE35 construct, 14 dpi. Center lines show the medians of three independent experiments (n > 25 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess significant differences (*α < 0.05; **α < 0.01; ***α < 0.001). B, Analysis of MtCLE35 expression by RT-qPCR in roots transformed with an Ubi:GUS control construct or a Ubi:MtCLE35 construct. Center lines show the medians of two biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Data are normalized relative to the Ubi:GUS control to highlight fold changes, as indicated with the dotted line. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between genotypes (∗∗∗P < 0.001). C, Infection threads number (left panel) and density (infection threads/cm of roots; right panel) of WT roots transformed with an empty vector control or with a Ubi:MtCLE35 construct, 5 dpi. Center lines show the medians of two independent experiments (n > 5 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess significant differences (*α < 0.05; **α < 0.01; ***α < 0.001).

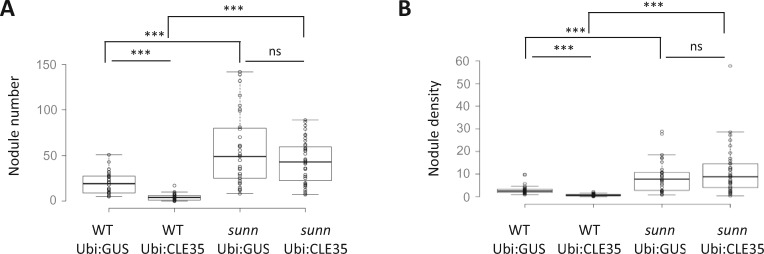

The MtCLE35 overexpression strategy was then comparatively performed in the WT and the sunn mutant (Figure 3). As expected, the “supernodulation” phenotype of sunn was observed, and in addition, the reduced nodule number (Figure 3A) and density (Figure 3B) induced by MtCLE35 ectopic expression was lost in the sunn mutant. Overall, these results indicate that the N-induced MtCLE35 peptide negatively regulates nodule number depending on the MtSUNN AON receptor.

Figure 3.

The SUNN receptor is required to mediate the MtCLE35 negative regulation of nodule number. Nodule number (A) and density (nodules/mg of root dry weight; B) of WT or sunn mutant roots transformed with a Ubi:GUS control construct or a Ubi:MtCLE35 construct, 14 dpi. Center lines show the medians of two independent experiments (n > 25 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (***α < 0.001; ns, not significant).

MtCLE35 represses the expression of miR2111

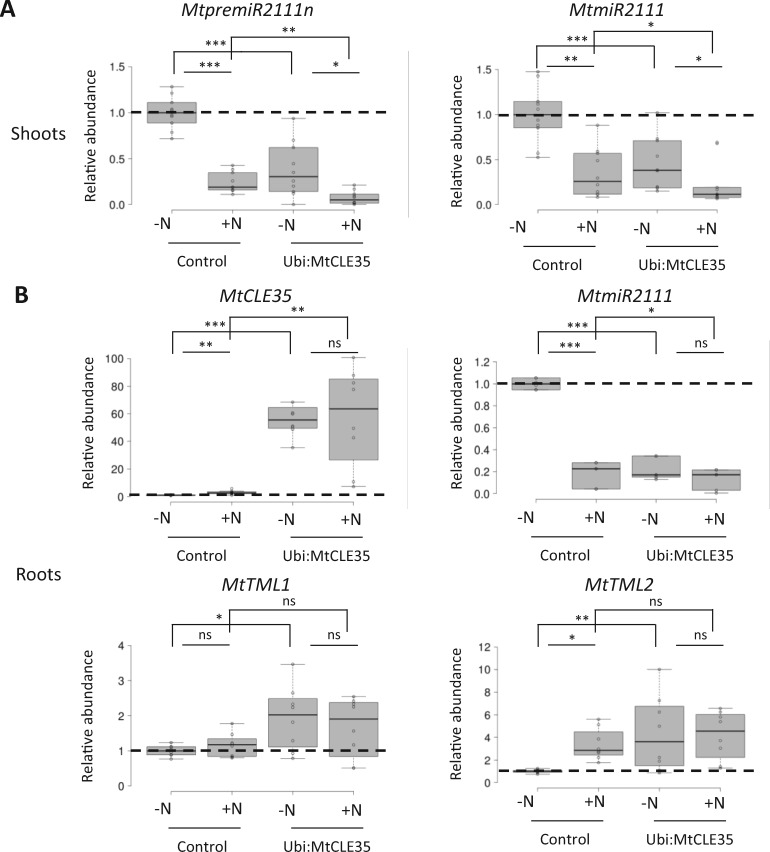

Knowing that the negative regulation of nodulation exerted by the MtSUNN pathway acts through the repression of miR2111 accumulation (Gautrat et al., 2020), we analyzed transcripts levels of MtpremiR2111 and MtTML genes, as well as miR2111 accumulation, in the shoots and roots of composite plants ectopically expressing MtCLE35 in their roots and grown under low- or high-N conditions (Figure 4). In WT plants, high N decreased the expression of MtpremiR2111 genes in shoots (Figure 4A;Supplemental Figure S4), the MtpremiR2111n precursor being previously demonstrated to be representative of the expression pattern of the different miR2111 precursors family (Gautrat et al., 2020). miR2111 accumulation was decreased as well in both shoots and roots (Figure 4, A and B). The ectopic expression of MtCLE35 in roots also decreased MtpremiR2111 expression in shoots (Figure 4A;Supplemental Figure S4) and miR2111 accumulation in both shoots and roots (Figure 4, A and B), independently of N levels. Conversely, MtTML1 and MtTML2 transcript levels were high in conditions where miR2111 levels were low, namely in WT roots grown on high N, and in MtCLE35 overexpressing roots, independently of N availability (Figure 4B). As a control, MtCLE35 transcripts were quantified, validating that Ubi:CLE35 roots indeed overexpressed the transgene (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

MtCLE35 ectopic expression represses miR2111 accumulation under low-N conditions and enhances TML transcripts accumulation. A, Analysis of MtpremiR2111n transcript levels by RT-qPCR (left panel) and of the accumulation of the major miR2111 isoform by stem–loop RT-qPCR (right panel), performed in shoots of WT plants with roots transformed with an Ubi:GUS control construct or an Ubi:MtCLE35 construct, which were grown for 8 d with (+N) or without (−N) NH4NO3 10 mM. B, Analysis of MtCLE35 (left upper panel), MtTML1 (left lower panel), and MtTML2 (right lower panel) transcript levels by RT-qPCR, and of the accumulation of the major miR2111 isoform by stem–loop RT-qPCR (right upper panel), in roots of the same plants as described in A. Center lines show the medians of five independent biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition) for shoots, and respectively of four and three independent biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition) for TML and miR2111 quantifications in roots; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Data were normalized to 1 relatively to the WT control grown without N (−N), as indicated with dotted lines. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ns, not significant).

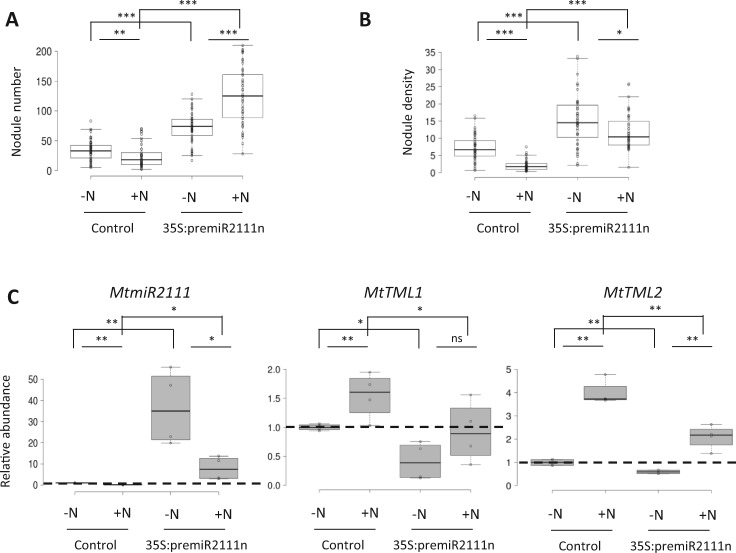

miR2111 ectopic expression partially bypasses N inhibition of nodulation

As MtCLE35 inhibits nodulation and represses miR2111 accumulation, we then tested if miR2111 ectopic expression was sufficient to bypass N inhibition of nodulation. In WT plants, N reduced the number of nodules formed (Figure 5A), as expected, as well as the nodule density (nodule number normalized to the root dry weight; Figure 5B), indicating that the observed nodulation phenotype was independent of N effects on root growth. MtpremiR2111n ectopic expression increased nodule number and density (Figure 5, A and B), under low-N conditions and also in the presence of N. The MtpremiR2111n transgene and miR2111 accumulated as expected in 35S:premiR2111n roots, independently of N conditions (Figure 5C). Conversely, transcript levels of MtTML1 and MtTML2 targets of miR2111 decreased in miR2111-overexpressing roots, also independently of N availability (Figure 5C). Overall, these results indicate that overexpression of miR2111 is sufficient to partially bypass N inhibition of nodulation.

Figure 5.

miR2111 ectopic expression partially bypasses the NON and represses TML transcripts accumulation. Nodule number (A) and density (nodules/mg of root dry weight; B) of WT plants with roots transformed with an empty vector control construct or a 35S:premiR2111n construct, 14 dpi with (+N) or without (−N) KNO3 2 mM. Center lines show the medians of two independent experiments (n > 22 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (*α < 0.05; **α < 0.01; ***α < 0.001). C, Analysis of the accumulation of the major miR2111 isoform by stem–loop RT-qPCR (left panel), and of MtTML1 (middle panel) or MtTML2 (right panel) transcript levels by RT-qPCR, performed in roots of plants described in A and B grown for 8 d with (+N) or without (−N) 10 mM NH4NO3. Center lines show the medians of two independent biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Data were normalized to 1 relatively to the WT control grown without N (−N), as indicated with dotted lines. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01).

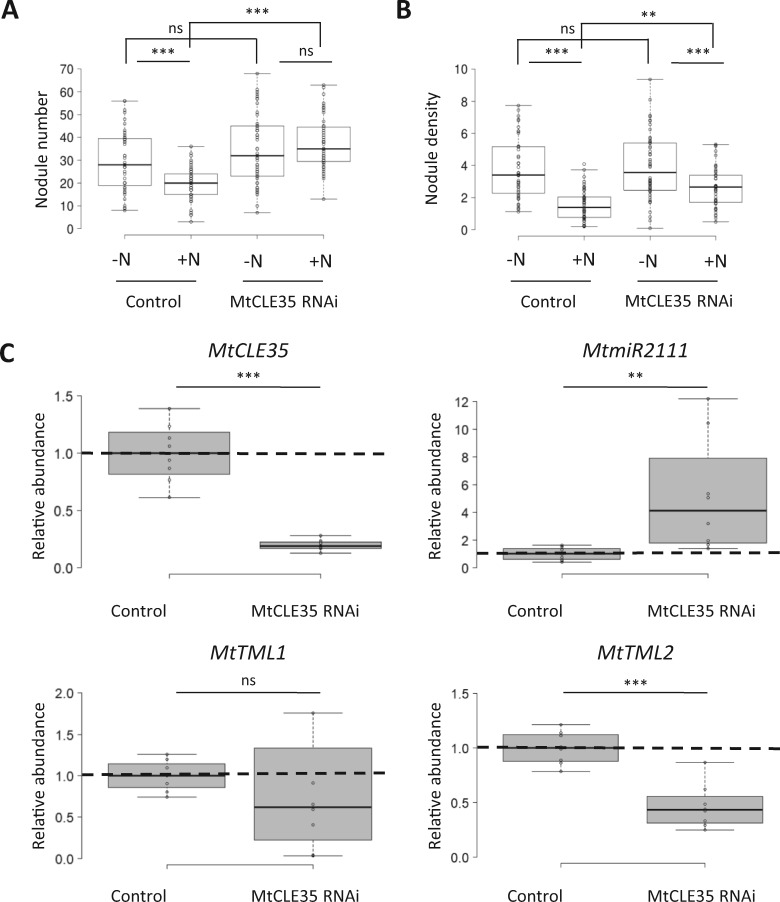

Downregulation of MtCLE35 expression upregulates miR2111 accumulation and is sufficient to partially bypass N inhibition of nodulation

As MtCLE35 ectopic expression constitutively repressed miR2111 independently of N availability, we thus tested if a MtCLE35 RNAi approach would lead to the opposite result, that is, a constitutive accumulation of miR2111 previously shown to allow a partial bypass of N inhibition of nodulation, using two independent RNAi constructs targeting different regions of the CLE35 gene (highlighted in yellow in the Supplemental Figure S3B). Independently of the construct used, MtCLE35 RNAi roots revealed an increased nodule number (Figure 6A;Supplemental Figure S5A) and density (Figure 6B;Supplemental Figure S5B), even under N conditions inhibiting nodulation in the WT. Analysis of CLE35 expression in Ubi:MtCLE35 RNAi roots, in comparison to the CLE12 and CLE13 genes that were previously also shown to inhibit nodulation (Mortier et al., 2010), validated the efficiency and the specificity of the RNAi approach (Supplemental Figure S6). Under high N, corresponding to the condition where CLE35 expression is induced (Figure 1C), the constitutive downregulation of CLE35 expression in MtCLE35 RNAi roots led to a significant accumulation of miR2111, whereas MtTML2 transcripts levels were repressed (Figure 6C). The expression of MtTML1 was, however, not significantly altered in MtCLE35 RNAi roots. Overall, these results show that downregulation of MtCLE35 expression is sufficient to partially impede N repression of miR2111 accumulation and to bypass N inhibition of nodulation.

Figure 6.

MtCLE35 RNAi partially bypasses the NON, increases miR2111 accumulation under high-N conditions, and represses TML2 transcript accumulation. Nodule number (A) and density (nodules/mg of root dry weight; B) of WT plants with roots transformed with a GUS RNAi control construct or a MtCLE35 RNAi construct, 14 dpi with (+N) or without (−N) KNO3 2 mM. Center lines show the medians of two independent experiments (n > 25 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. A Mann–Whitney test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (**α < 0.01; ***α < 0.001; ns, not significant). C, Analysis of MtCLE35 (left upper panel), MtTML1 (left lower panel), and MtTML2 (right lower panel) transcript levels by RT-qPCR, and of the accumulation of the major miR2111 isoform by stem–loop RT-qPCR (right upper panel), in roots of plants described in A and B grown for 8 d with 10 mM NH4NO3 (+N). Center lines show the medians of five independent biological replicates (n > 3 plants for each replicate and condition); box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots. Data were normalized to 1 relatively to the WT control grown without N (−N), as indicated with dotted lines. A Student’s t test was performed to assess significant differences between N treatments or between genotypes (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, we characterized a CLE peptide-encoding gene, MtCLE35, which is locally induced by high N and negatively regulates nodulation depending on the MtSUNN receptor, which was anticipated to exist based on previous knowledge gained in L. japonicus, soybean, and common bean (Okamoto et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2011; Nishida et al., 2016), but not yet functionally studied in M. truncatula. We show in addition that this MtCLE35/MtSUNN pathway recruits the miR2111/TML module, as recently reported for the rhizobium-induced AON pathway both in L. japonicus and M. truncatula (Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2020). Accordingly, the MtCLE35/MtSUNN and the miR2111/TML pathways inhibit rhizobial infections in both legume plants, as well as MtENOD11 expression and NF perception genes (Mortier et al., 2010; Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2020; this study). This indicates that an extensive overlap exists between nitrate-induced and rhizobium-induced systemic pathways that limit the number of nodules formed on plant root systems. In agreement with such overlap, several CLE peptide-encoding genes are induced by both rhizobium and nitrate, including the LjCLE-RS2 gene in L. japonicus and the closely related MtCLE35 gene in M. truncatula characterized in this study. In addition, the supernodulation phenotype of the sunn mutant is nitrate insensitive (Sagan et al., 1995). Accordingly, constitutive ectopic expression of miR2111 or downregulation of MtCLE35 is sufficient to cause partially nitrate-resistant nodulation. Overall, this extends the previously identified similarities between rhizobium- and nitrate-induced inhibition of nodulation, indicating that the NON pathway shares core components with the AON pathway.

This similarity also encompasses the regulation of CLE peptides inhibiting nodulation by rhizobium and/or nitrate. Indeed, rhizobium-induced CLE peptides, such as MtCLE12 and MtCLE13 in M. truncatula, require the activity of the NIN transcription factor (Mortier et al., 2010; Laffont et al., 2020), whereas the MtCLE35 gene requires the NIN-Like protein MtNLP1 for its nitrate induction (this study). NLP genes were previously related to nitrate root responses, initially in Arabidopsis (Castaings et al., 2009) and more recently in legumes in relation to the NON (Lin et al., 2018; Nishida et al., 2018). Indeed, LjNLP4/NRSYM1 mediates the nitrate induction of LjCLE-RS2, and even though a link with CLE genes was not established in M. truncatula, MtNLP1 is similarly required for the NON. Together with the observation that two putative NRE cis-elements are detected in the MtCLE35 promoter, these results reveal that the NLP requirement for upregulating NON CLE genes by nitrate is conserved between the two model legumes. It remains to be determined, however, if in non-legume plants, or even in nonsymbiotic plants such as Arabidopsis, NLP transcription factors also contribute to the regulation of N-related CLE peptides or not. In soybean, CLE peptides inhibiting nodulation seem to be either regulated by rhizobium (RIC) or by nitrate (NIC; Lim et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2011), which is in contrast to L. japonicus and M. truncatula where CLE genes upregulated both by nitrate and rhizobium have been identified (Okamoto et al., 2009; Nishida et al., 2016), such as MtCLE35, pointing to differential recruitment of NIN versus NLP transcription factors depending on legume species.

High N induces local MtCLE35 expression in roots and also systemically represses the expression of miR2111 precursors in shoots, and thus the systemic accumulation of miR2111 in both shoots and roots, mimicking the regulation observed in response to rhizobium (Tsikou et al., 2018; Gautrat et al., 2020; this study). This regulation is functionally linked to the NON, as inducing constitutive miR2111 levels or reducing CLE35 activity can partially bypass the NON. However, this nitrate-resistance phenotype is intermediate, suggesting the existence of alternative local and/or systemic N-induced pathways in addition to the MtNLP1/CLE35/SUNN/miR2111/TML pathway, as also previously proposed in L. japonicus (Nishida et al., 2018).

Surprisingly, whereas regulation of the MtTML2 miR2111 target by high N and its deregulation upon MtCLE35 RNAi downregulation were clearly observed, regulation of MtTML1 was much more subtle, or even not detected, respectively. The same result was previously noticed for MtTML gene regulation in response to rhizobium (Gautrat et al., 2020), highlighting differential expression control of the two M. truncatula TML homologs. Of note, miR2111 action on both TML targets is similar, based on ectopic miR2111 or mimicry approaches (Gautrat et al., 2020), and thus cannot explain such differential behavior. The functional relevance of the duplication of TML targets of miR2111 in M. truncatula, which seems not evolutionary conserved in L. japonicus where a single TML gene is reported (Takahara et al., 2013; Gautrat et al., 2019), remains unknown, similar to the signals that are causal for such differential expression independently of miR2111 post-transcriptional regulation.

In Arabidopsis, a subset of CLE peptide-encoding genes, AtCLE1/3/4/7, was linked to the regulation of root development and nitrate acquisition (Araya et al., 2014). Unexpectedly, these AtCLE genes are phylogenetically most closely related to the AON/NON legume CLE genes (Hastwell et al., 2017), even though their expression is upregulated by opposite N conditions, namely N deficit or N provision. It remains to be explored if CLE genes induced by N exist in Arabidopsis, and whether they regulate root development and/or N acquisition antagonistically to the already known AtCLE genes induced by N deficit. Conversely, low N-induced CLE peptides likely also exist in legumes, and notably in M. truncatula (De Bang et al., 2017); however, these remain to be characterized in relation to a potential function in regulating nodulation. The dynamic integration of these potential high- and low-N CLE peptides in the regulation of different stages of root and nodule development, as well as N acquisition, thus needs further research. Similarly, the integration of the role of these N-related CLE peptides with the low-N activation of another type of signaling peptide, the C-terminally Encoded Peptides (CEPs), which are evolutionary conserved between Arabidopsis and legume plants despite their differential role in the regulation of root system architecture (Imin et al., 2013; Mohd-Radzman et al., 2016; Chapman et al., 2019, 2020), should be explored. A detailed understanding of how these N-regulated signaling peptide regulatory pathways intersect to allow plant adaptation to N limitation depending on whole-plant needs is a promising avenue to improve plant N-use efficiency in heterogeneous and fluctuating environments, such as those faced in low-fertilizer, agro-ecological systems.

Materials and methods

Biological material, plant growth conditions, and experimental treatments

The M. truncatula Jemalong A17 genotype and the sunn-4 mutant derived from this genotype (Schnabel et al., 2005) were used in this study, as well as the R108 genotype and the nlp1.2 mutant derived from this genotype (Lin et al., 2018). Seeds were scarified by immersion in pure sulfuric acid for 3 min, washed 6 times with water, and then sterilized for 20 min in Bayrochlore (3.75 g/L; Bayrol, Chlorofix, Planegg, Germany). Seeds were washed again, transferred onto water/BactoAgar plates (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), stratified for 4 d in the dark at 4°C, and then germinated at 24°C in the dark for one night.

For in vitro experiments, seedlings were placed onto a growth culture paper (Mega International, https://mega-international.com/) in vertical 1.5% BactoAgar plates containing Fahraeus medium (Fahraeus, 1957) with N (NH4NO3 10 mM for split root experiments, following Ruffel et al. (2008), and KNO3 10 mM for the nlp1 R108 experiment, following Lin et al. (2018), in a growth chamber with a 16-h photoperiod, a light intensity of 150 µE, and a temperature of 24°C.

Split-roots were generated by cutting primary roots of seedlings 5-d post-germination, which were then grown in between two growth papers for 1 week to favor split-root growth, and an additional week without growth paper. Plants with two homogeneous neo-formed roots were then selected and transferred onto Fahraeus medium plates where the agar was separated into two parts. Two different split-root experimental set-ups were used: First, plants with half root systems on KNO3 0.2 mM as an N deficit-inducing condition, or on NH4NO3 10 mM as an N satiety-inducing condition, corresponding to the local treatments; and the other half of the root system being placed on a medium without N, corresponding to the systemic roots, distant from the local treatment. A second split-root experiment used plants with half root systems inoculated with rhizobium and without N (see below), corresponding to the local treatment, the other half of the root system being placed on a medium without rhizobium, corresponding to systemic roots. In each case, split-root plants challenged, respectively, with a homogenous N deficit or N satiety, or homogeneously inoculated with rhizobium, were used as controls.

For composite plant experiments (see below), seedlings grown in vitro were transferred on a medium with NH4NO3 10 mM for RT-quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses, based on Ruffel et al. (2008), and on KNO3 2 mM for experiments aiming to rescue the N inhibition of nodulation.

For nodulation experiments, plants were transferred into pots containing a sand:perlite 1:3 mixture, placed in a growth chamber with a 16-h photoperiod, a light intensity of 150 µE, a temperature of 24°C, and 65% relative humidity. Plants were watered with an ‘‘i’’ growth medium (Blondon, 1964) with low N (KNO3 0.25 mM) or high N (KNO3 2 mM or NH4NO3 10 mM), depending on experiments and as described before. A Sinorhizobium medicae WSM419 strain expressing a LacZ reporter gene (ProHemA:LacZ; Terpolilli et al., 2008) was used to nodulate M. truncatula plants. Bacteria were grown overnight at 30°C on a Yeast Extract Broth medium, and roots were then inoculated with a bacterial suspension at an Optical Density OD600nm = 0.05. Nodule number and root dry weight were measured 14-d post rhizobium inoculation (dpi).

Long and small RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNAs were extracted using the Quick-RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) from shoots and/or roots of non-inoculated or N-treated plants 8 d after transfer in sand:perlite pots, or from split-root plants 8 d after transfer in the ±N condition, or from split-root plants 5 d after transfer on the ± rhizobium condition. Extracted RNAs were then treated with a DNase1 RNase-free (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA), following manufacturer instructions. cDNAs were obtained using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/mL), following manufacturer instructions. A stem–loop Reverse Transcription was performed to amplify specifically mature miRNAs after including dedicated adapters (listed in the Supplemental Table S1), as described in Gautrat et al. (2020). Two independent cDNA samples were generated from each RNA sample, as technical replicates.

Gene expression was then analyzed by qPCR on a LightCycler96 apparatus (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), using the Light Cycler 480 SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and dedicated specific primers to amplify each gene of interest (listed in the Supplemental Table S1). Forty amplification cycles were performed (15 s at 95°C, 15 s at 60°C, 15 s at 72°C), and a final melting curve of 60°C–95°C was used to assess the amplification specificity. Amplicons were independently sequenced to confirm the specificity of the PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) amplification. Primer efficiency was systematically tested, and only those with an efficiency of 90% were retained. Gene expression was normalized using two different reference genes, MtActin11 and MtRNA-binding protein 1 (MtRBP1), whereas miRNA accumulation was normalized using the miR162 mature miRNA. In figures, the MtRBP1 reference gene was selected to normalize the data.

Similarity tree building

The similarity tree was built using the Seaview version 4 software (Gouy et al., 2010). CLE peptide precursor protein sequences were retrieved from the M. truncatula genome browser version 5.0 (https://medicago.toulouse.inra.fr/MtrunA17r5.0-ANR/; Pecrix et al., 2018), from Hastwell et al. (2017) for L. japonicus and G. max proteins, and the A. thaliana Root Growth Factor 1 (RGF1) protein was used to root the tree. Proteins were aligned using MUSCLE, genetic relationships were obtained with a maximum likelihood approach, and the similarity tree was generated with PhyML using an LG substitution model with 1,000 bootstraps.

LacZ staining

To quantify rhizobial infection events, a LacZ staining was performed to follow infection threads. Five dpi roots were stained, using a β-galactosidase histochemical assay as described in Ardourel et al. (1994); infection threads were observed as blue staining with a stereomicroscope (Axio Zoom, Zeiss) under bright field. The length of roots was measured using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012; https://imagej.nih.gov/) to calculate the infection thread density per centimeter of root.

Cloning procedures and root transformation

The Ubi:CLE35 construct was generated using a Golden Gate strategy and vectors described in Engler and Marillonnet (2014). The MtCLE35 open reading frame was amplified by PCR using primers indicated in Supplemental Table S1. This PCR amplicon was inserted into the L1 Golden Gate vector (EC47811, ampicillin resistant) together with the AtUbi promoter (EC15062) and the 35S terminator (EC41414) cassettes provided by the Engineering N Symbiosis for Africa (ENSA) project. After validation by sequencing of the L1 vector, an L2 vector (EC50507) was produced by adding a pNOS: Kanamycin cassette (EC15029) to allow plant selection on kanamycin. A AtUbi:GUS control vector was generated with the same strategy, using the GUS cassette (EC75111) available from the ENSA project.

Two independent MtCLE35 RNAi constructs were generated by amplifying by PCR a 259-nt MtCLE35 (RNAi#1) or a 211-nt MtCLE35 (RNAi#2) product corresponding to regions shown in the Supplemental Figure S3B, using primers shown in Supplemental Table S1, and inserted into the pDonR207 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). This entry vector was then recombined using Gateway technology with the pFRN vector (Gonzalez-Rizzo et al., 2006) containing a 35S-Cauliflower Mosaic Virus promoter, and the construct was validated by sequencing.

Final binary vectors were transformed into the Agrobacterium rhizogenes Arqua1 strain to generate “composite plants” having WT shoots and transformed roots, selected for 2 weeks on Fahraeus medium with kanamycin (25 mg/mL), following the protocol described in Boisson-Dernier et al. (2001).

Statistical analyses and softwares used

Statistical analyses were performed with R (http://www.R-project.org/) and the Rstudio software (http://www.rstudio.com/), using a Mann–Whitney test for nodulation phenotyping and a Student’s t test for RT-qPCR experiments.

Boxplots were generated using tools available at http://shiny.chemgrid.org/boxplotr/. The FIMO software (http://meme-suite.org/index.html) was used to identify NRE cis-elements in 5-kb promoters and calculate associated P-values (Cuellar-Partida et al., 2012). The logo motif was designed using Weblogo (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found using accession numbers listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 MtCLE34 expression in M. truncatula roots.

Supplemental Figure S2 The expression of MtCLE35 is locally induced by rhizobium.

Supplemental Figure S3 MtCLE35 gene, protein, and promoter sequences.

Supplemental Figure S4 The expression of miR2111 precursors is repressed by MtCLE35 overexpression and high N.

Supplemental Figure S5 An independent MtCLE35 RNAi construct also partially bypasses the NON.

Supplemental Figure S6 Efficiency and specificity of the MtCLE35 RNAi approach.

Supplemental Table S1 List of primers used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marc Lepetit (LSTM, INRA-Montpellier, France) for help in designing the conditions used for low N/N deficit and high N/N satiety in M. truncatula, Fang Xie (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) for providing seeds of the nlp1-2 mutant, and Carole Laffont (IPS2) for advice on some experiments. Golden Gate cassettes were provided by the ENSA project, and funding by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche through the Saclay Plant Sciences Labex/EUR and the PSYCHE project.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no competing interests.

F.F. designed the project; C.M. performed experiments, with help from P.G.; F.F. and C.M. analyzed and interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript, with help from P.G.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instruction for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys) is: Florian Frugier (florian.frugier@cnrs.fr).

References

- Araya T, Miyamoto M, Wibowo J, Suzuki A, Kojima S, Tsuchiya YN, Sawa S, Fukuda H, Von Wirén N, Takahashi H (2014) CLE-CLAVATA1 peptide-receptor signaling module regulates the expansion of plant root systems in a nitrogen-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 2029–2034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardourel M, Demont N, Debelle F, Maillet F, de Billy F, Prome JC, Denarie J, Truchet G (1994) Rhizobium meliloti lipooligosaccharide nodulation factors: different structural requirements for bacterial entry into target root hair cells and induction of plant symbiotic developmental responses. Plant Cell 6: 1357–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bang TC, Lundquist PK, Dai X, Boschiero C, Zhuang Z, Pant P, Torres-Jerez I, Roy S, Nogales J, Veerappan V, et al. (2017) Genome-wide identification of Medicago peptides involved in macronutrient responses and nodulation. Plant Physiol 175: 1669–1689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondon F (1964) Contribution à l’étude du développement des graminées fourragères ray-grass et dactyle. Thèse de l'Université de Paris, Faculté des Sciences, Paris, France

- Boisson-Dernier A, Chabaud M, Garcia F, Bécard G, Rosenberg C, Barker DG (2001) Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Medicago truncatula for the study of nitrogen-fixing and endomycorrhizal symbiotic associations. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14: 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano-Anolles G, Gresshoff PM (1991) Plant genetic control of nodulation. Annu Rev Microbiol 45: 345–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaings L, Camargo A, Pocholle D, Gaudon V, Texier Y, Boutet-Mercey S, Taconnat L, Renou JP, Daniel-Vedele F, Fernandez E. et al. (2009) The nodule inception-like protein 7 modulates nitrate sensing and metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant J 57: 426–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman K, Ivanovici A, Taleski M, Sturrock CJ, Ng JLP, Mohd-Radzman NA, Frugier F, Bennett MJ, Mathesius U, Djordjevic MA (2020) CEP receptor signalling controls root system architecture in Arabidopsis and Medicago. New Phytol 226: 1809–1821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman K, Taleski M, Ogilvie HA, Imin N, Djordjevic MA (2019) CEP-CEPR1 signalling inhibits the sucrose-dependent enhancement of lateral root growth. J Exp Bot 70: 3955–3967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar-Partida G, Buske FA, McLeay RC, Whitington T, Stafford Noble W, Bailey TL (2012) Epigenetic priors for identifying active transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 28: 56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C, Marillonnet S (2014) DNA cloning and assembly methods. Methods Mol Biol 1116: 1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahraeus G (1957) The infection of clover root hairs by nodule bacteria studied by a simple glass slide technique. J Gen Microbiol 16: 374–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JC (2020) Recent advances in Arabidopsis CLE peptide signaling. Trends Plant Sci 25: 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautrat P, Laffont C, Frugier F (2020) Compact root architecture 2 promotes root competence for nodulation through the miR2111 systemic effector. Curr Biol 30: 1339–1345.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautrat P, Mortier V, Laffont C, De Keyser A, Fromentin J, Frugier F, Goormachtig S (2019) Unraveling new molecular players involved in the autoregulation of nodulation in Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot 70: 1407–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goad DM, Zhu C, Kellogg EA (2017) Comprehensive identification and clustering of CLV3/ESR-related (CLE) genes in plants finds groups with potentially shared function. New Phytol 216: 605–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rizzo S, Crespi M, Frugier F (2006) The Medicago truncatula CRE1 cytokinin receptor regulates lateral root development and early symbiotic interaction with Sinorhizobium meliloti. Plant Cell 18: 2680–2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O (2010) Sea view version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol 27: 221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastwell AH, De Bang TC, Gresshoff PM, Ferguson BJ (2017) CLE peptide-encoding gene families in Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus, compared with those of soybean, common bean and Arabidopsis. Sci Rep 7: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa Y, Sawa S (2019) Diverse function of plant peptide hormones in local signaling and development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 51: 81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imin N, Mohd-Radzman NA, Ogilvie HA, Djordjevic MA (2013) The peptide-encoding CEP1 gene modulates lateral root and nodule numbers in Medicago truncatula. J Exp Bot 64: 5395–5409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusell L, Madsen LH, Sato S, Aubert G, Genua A, Szczyglowski K, Duc G, Kaneko T, Tabata S, De Bruijn F. et al. (2002) Shoot control of root development and nodulation is mediated by a receptor-like kinase. Nature 420: 422–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffont C, Ivanovici A, Gautrat P, Brault M, Djordjevic MA, Frugier F (2020) The NIN transcription factor coordinates CEP and CLE signaling peptides that regulate nodulation antagonistically. Nat Commun 11: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim CW, Lee YW, Hwang CH (2011) Soybean nodule-enhanced CLE peptides in roots act as signals in gmnark-mediated nodulation suppression. Plant Cell Physiol 52: 1613–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J shun, Li X, Luo ZL, Mysore KS, Wen J, Xie F (2018) NIN interacts with NLPs to mediate nitrate inhibition of nodulation in Medicago truncatula. Nat Plants 4: 942–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magori S, Oka-Kira E, Shibata S, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Hase Y, Tanaka A, Sato S, Tabata S, Kawaguchi M (2009) Too Much Love, a root regulator associated with the long-distance control of nodulation in Lotus japonicus. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 22: 259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Radzman NA, Laffont C, Ivanovici A, Patel N, Reid D, Stougaard J, Frugier F, Imin N, Djordjevic MA (2016) Different pathways act downstream of the CEP peptide receptor CRA2 to regulate lateral root and nodule development. Plant Physiol 171: 2536–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier V, den Herder G, Whitford R, van de Velde W, Rombauts S, D’haeseleer K, Holsters M, Goormachtig S (2010) CLE peptides control Medicago truncatula nodulation locally and systemically. Plant Physiol 153: 222–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida H, Handa Y, Tanaka S, Suzaki T, Kawaguchi M (2016) Expression of the CLE-RS3 gene suppresses root nodulation in Lotus japonicus. J Plant Res 129: 909–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida H, Tanaka S, Handa Y, Ito M, Sakamoto Y, Matsunaga S, Betsuyaku S, Miura K, Soyano T, Kawaguchi M. et al. (2018) A NIN-LIKE PROTEIN mediates nitrate-induced control of root nodule symbiosis in Lotus japonicus. Nat Commun 9: 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto S, Ohnishi E, Sato S, Takahashi H, Nakazono M, Tabata S, Kawaguchi M (2009) Nod factor/nitrate-induced CLE genes that drive HAR1-mediated systemic regulation of nodulation. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecrix Y, Staton SE, Sallet E, Lelandais-Brière C, Moreau S, Carrère S, Blein T, Jardinaud MF, Latrasse D, Zouine M, et al. (2018) Whole-genome landscape of Medicago truncatula symbiotic genes. Nat Plants 4: 1017–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid DE, Ferguson BJ, Gresshoff PM (2011) Inoculation- and nitrate-induced CLE peptides of soybean control NARK-dependent nodule formation. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 24: 606–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Liu W, Nandety RS, Crook A, Mysore KS, Pislariu CI, Frugoli J, Dickstein R, Udvardi MK (2020) Celebrating 20 years of genetic discoveries in legume nodulation and symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Plant Cell 32: 15–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffel S, Freixes S, Balzergue S, Tillard P, Jeudy C, Martin-Magniette ML, Van Der Merwe MJ, Kakar K, Gouzy J, Fernie AR, et al. (2008) Systemic signaling of the plant nitrogen status triggers specific transcriptome responses depending on the nitrogen source in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 146: 2020–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagan M, Morandi D, Tarenghi E, Duc G (1995) Selection of nodulation and mycorrhizal mutants in the model plant Medicago truncatula (Gaertn.) after γ-ray mutagenesis. Plant Sci 111: 63–71 [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel E, Journet EP, De Carvalho-Niebel F, Duc G, Frugoli J (2005) The Medicago truncatula SUNN gene encodes a CLV1-like leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase that regulates nodule number and root length. Plant Mol Biol 58: 809–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle IR, Men AE, Laniya TS, Buzas DM, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Carroll BJ, Gresshoff PM (2003) Long-distance signaling in nodulation directed by a CLAVATA1-like receptor kinase. Science 299: 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Yoro E, Kawaguchi M (2015) Leguminous plants: inventors of root nodules to accommodate symbiotic bacteria. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 316: 111–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahara M, Magori S, Soyano T, Okamoto S, Yoshida C, Yano K, Sato S, Tabata S, Yamaguchi K, Shigenobu S, et al. (2013) TOO MUCH LOVE, a novel kelch repeat-containing F-box protein, functions in the long-distance regulation of the LEGUME-rhizobium symbiosis. Plant Cell Physiol 54: 433–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpolilli JJ, O’Hara GW, Tiwari RP, Dilworth MJ, Howieson JG (2008) The model legume Medicago truncatula A17 is poorly matched for N2 fixation with the sequenced microsymbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021. New Phytol 179: 62–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikou D, Yan Z, Holt DB, Abel NB, Reid DE, Madsen LH, Bhasin H, Sexauer M, Stougaard J, Markmann K (2018) Systemic control of legume susceptibility to rhizobial infection by a mobile microRNA. Science 362: 233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao TT, Schilderink S, Moling S, Deinum EE, Kondorosi E, Franssen H, Kulikova O, Niebel A, Bisseling T (2014) Fate map of Medicago truncatula root nodules. Development 141: 3517–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.