Resumo

Fundamento

A relação entre velocidade de onda de pulso (VOP) e biomarcadores de mudanças estruturais do ventrículo esquerdo e artérias carótidas ainda é pouco elucidada.

Objetivo

Investigar a relação entre VOP e esses biomarcadores.

Métodos

Estudo transversal, retrospectivo e analítico. Revisamos prontuários médicos de pacientes com diabetes mellitus, dislipidemia, e pré-hipertensão ou hipertensão, que realizaram medida de pressão arterial central (PAC) utilizando o Mobil-O-Graph®, e doppler de carótida ou ecocardiografia três meses antes ou após a medida da PAC. Análise estatística realizada por correlação de Pearson ou de Spearman, análise de regressão múltipla e de regressão bivariada, e teste t (independente) ou de Mann-Whitney. Um p<0,05 indicou significância estatística.

Resultados

Prontuários de 355 pacientes foram avaliados, 56,1 ±14,8 anos, 51% homens. A VOP correlacionou-se com espessuras da íntima média (EIM) das carótidas (r=0,310) do septo do ventrículo esquerdo (r=0,191) e da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo (r=0.215), e com diâmetro do átrio esquerdo (r=0,181). A EIM associou-se com VOP ajustada por idade e pressão sistólica periférica (p=0,0004); uma EIM maior que 1mm aumentou em 3,94 vezes a chance de se apresentar VOP acima de 10m/s. A VOP foi significativamente maior em indivíduos com hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo (p=0,0001), EIM > 1 mm (p=0,006), placa de carótida (p=0,0001), estenose ≥ 50% (p=0,003), e lesões de órgãos-alvo (p=0,0001).

Conclusões

A VOP correlacionou-se com a EIM e com parâmetros ecocardiográficos, e se associou independentemente com EIM. Essa associação foi mais forte em pacientes com hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo, EIM aumentada, placa de carótida, estenose ≥ 50%, e lesões de órgãos-alvo. (Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020; 115(6):1125-1132)

Keywords: Doenças Cardiovasculares/mortalidade, Pressão Arterial, Fatores de Risco, Hipertensão, Disfunção Ventricular Esquerda, Diabetes Mellitus

Introdução

A alta prevalência e a elevada mortalidade das doenças cardiovasculares (DCVs) destacam a urgente necessidade de se implementar ferramentas para melhor estratificação de risco cardiovascular, identificar os pacientes em alto risco, e diagnosticar e tratar precocemente as doenças. Uma dessas ferramentas são os biomarcadores cardiovasculares, os quais conseguem detectar as DCVs em sua fase subclínica, com boa acurácia, melhorando, assim, a prevenção de eventos e o cenário epidemiológico.1 , 2

Alguns dos principais biomarcadores relacionados à estrutura e à função vascular são a espessura da íntima-média (EIM), presença de placas na artéria carótida, velocidade de onda de pulso (VOP), e o índice tornozelo-braquial (ITB).2Além disso, outros biomarcadores cardiovasculares são usados para identificar lesões de órgãos-alvo (LOA), tais como hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo, níveis elevados de creatinina sérica, excreção aumentada de albumina, e taxa de filtração glomerular reduzida.3 , 4

A VOP, um marcador de dano vascular utilizado na avaliação de rigidez arterial, é considerada um forte marcador independente de LOA e eventos adversos.5 A VOP também é um preditor de mortalidade por todas as causas, indicando o risco real do paciente.6 O aumento de um metro por segundo (1m/s) na VOP leva a um aumento de 14% no risco de eventos adversos e de 15% no risco cardiovascular e mortalidade por todas as causas.6 Entre suas vantagens, a VOP é um método não invasivo, fácil, de custo relativamente baixo, e amplamente validado,2 com valores de referência claramente estabelecidos.7 , 8Apesar dessas evidências, a VOP continua subutilizada na prática clínica, e poucos estudos analisaram sua relação com outros biomarcadores, especialmente utilizando o método oscilométrico. Assim, o objetivo deste estudo foi investigar a relação entre a VOP e outros biomarcadores das alterações estruturais cardiovasculares em pacientes com fatores de risco cardiovascular.

Métodos

Participantes

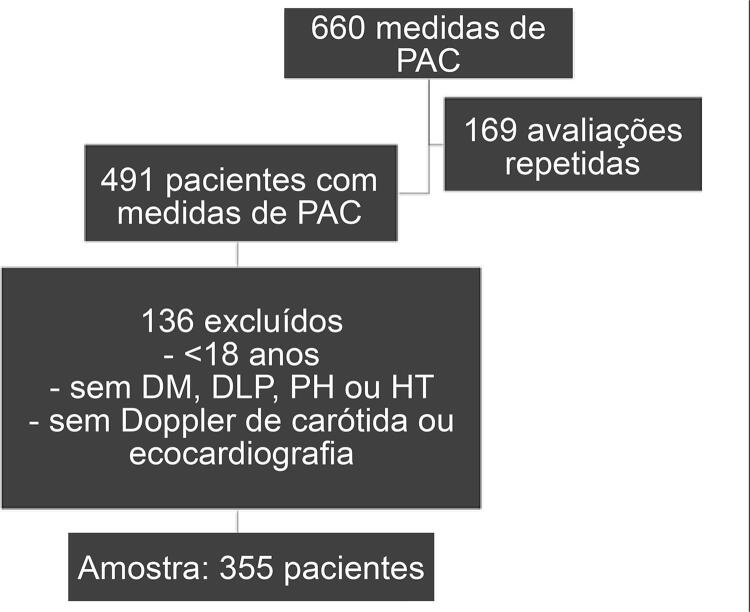

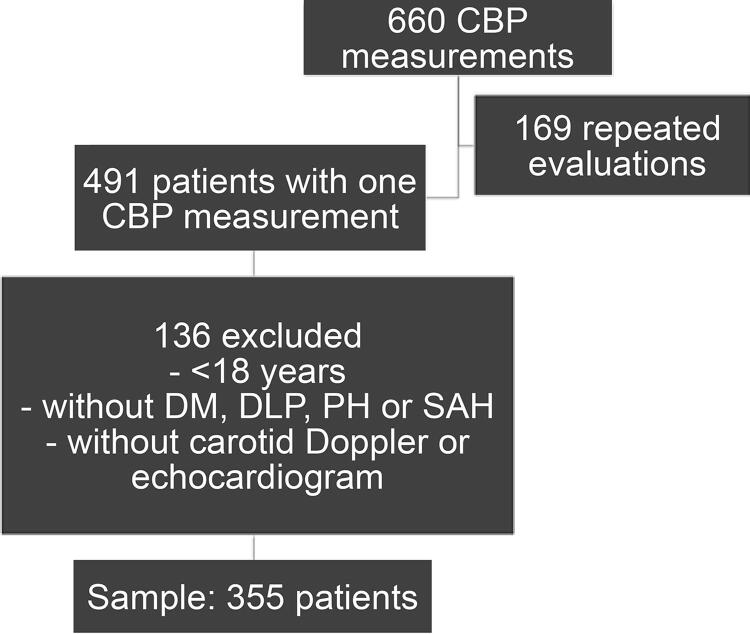

De setembro de 2012 a março de 2017, foram realizadas 660 medidas da pressão arterial central (PAC). Entre essas avaliações, 131 pacientes realizaram o exame duas vezes ou mais, totalizando 169 avaliações repetidas. Assim, a população do estudo foi composta por 491 pacientes que realizaram avaliações da PAC.

O cálculo da amostra baseou-se em um erro de 5% e nível de confiança de 95%, que indicou um tamanho amostral mínimo de 216 pacientes. A amostra do estudo consistiu em 355 pacientes brasileiros encaminhados a uma clínica de cardiologia para avaliação da PAC ( Figura 1 ).

Figura 1. – Fluxograma da seleção da amostra do estudo; PAC: pressão arterial central; DM: diabetes mellitus; PH: pré-hipertensão; HT: hipertensão.

Delineamento do Estudo e Procedimentos

Este estudo analítico, retrospectivo, transversal foi realizado a partir da análise de prontuários médicos e laudos de exames. Dados foram primeiramente coletados dos prontuários médicos do serviço de arquivo médico da instituição. Foram aplicados os seguintes critérios de exclusão: idade inferior a 18 anos, ausência dos seguintes diagnósticos: diabetes mellitus (DM), dislipidemia (DLP), pré-hipertensão (PH) ou hipertensão (HT); ausência de Doppler de carótida ou de ecocardiografia nos três meses antecedentes ou posteriores à medida de PAC ( Figura 1 ).

Os diagnósticos de todos os pacientes foram obtidos dos prontuários médicos e, quando esses não estavam disponíveis, os seguintes critérios diagnósticos foram usados – glicemia de jejum > 125 mg/dL ou uso de hipoglicemiantes para DM, níveis de triglicerídeos > 150 mg/dL e de lipoproteína de baixa densidade (LDL) > 100mg/dL e/ou de lipoproteína de alta densidade (HDL) < 40 mg/dL e/ou uso atual de estatinas para dislipidemia. Indivíduos com pressão arterial sistólica (PAS) periférica entre 121 e 139 mmHg e pressão arterial diastólica (PAD) entre 81 e 89 mmHg, medidas durante a avaliação da PAC, foram classificados como pré-hipertensos, e aqueles com pressão arterial igual ou superior a 140/90 mmHg foram classificados como hipertensos.4

Dados sobre as seguintes variáveis foram coletadas dos prontuários médicos: sexo (feminino ou masculino), tabagismo (sim ou não), e estado civil (com ou sem parceiro/a). Além dos resultados dos exames de imagem, resultados do Doppler de carótida e/ou ecocardiografia conduzidos nos três meses antes e após o exame de PAC foram analisados. Quando esses exames eram realizados mais de uma vez nesse período, os resultados do último teste antes da medida da PAC foram considerados para análise.

Medida da PAC

A PAC foi determinada pelo método validado, não-invasivo, oscilométrico, pelo equipamento Mobil-O-Graph® (IEM, Stolberg, Alemanha), com algoritmo ARCSolver.10 Todas as medidas foram realizadas pelo mesmo indivíduo, sempre das 13 horas às 14 horas, utilizando a análise tripla de onda de pulso e calibração MAD-c2 (pressão diastólica média).9 , 10 Idade foi calculada como a diferença entre a data de nascimento e a data da medida da PAC. Peso (Kg) e altura (m) foram usados para o cálculo do índice de massa corporal (IMC, Kg/m2) pela fórmula de Quetelet11 e sua classificação.12 PAS periférica (PASp), PAD periférica (PADp), PAS central (PASc), índice de aumento (IA), e VOP foram analisados.13 Todos os pacientes foram orientados a não fumar ou beber café antes do teste.

Doppler de Carótida e Ecocardiograma

Os exames de imagem foram realizados em diferentes centros de imagem, segundo escolha do paciente. Exames realizados na clínica de cardiologia em que ocorreu a coleta de dados foram conduzidos com equipamento de ultrassom Philips HD 11.

O Doppler de carótida foi realizado seguindo-se as diretrizes norte-americanas14 e europeia.15 Os valores mais altos obtidos das artérias carótidas comuns direita e esquerda foram considerados para a análise estatística.

Os parâmetros ecocardiográficos foram avaliados por ecocardiografia transtorácica bidimensional,16 com medidas da espessura do septo do ventrículo esquerdo (ESVE), da espessura da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo (EPPVE), e do diâmetro do átrio esquerdo (DAE).

Lesões de Órgãos-alvo

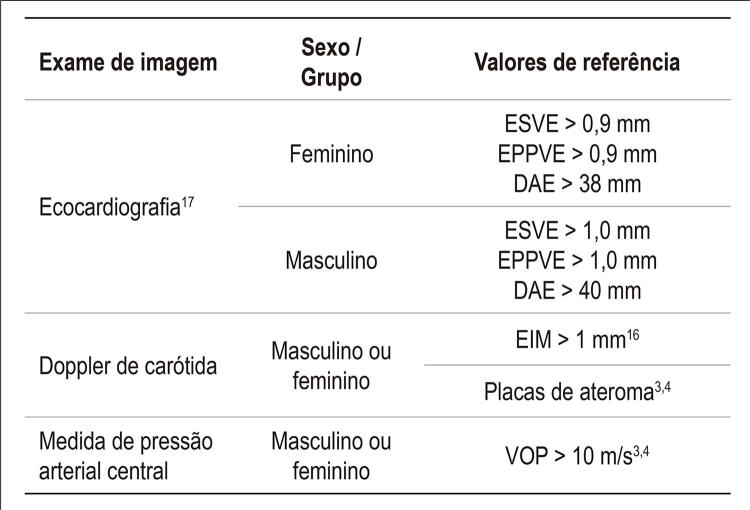

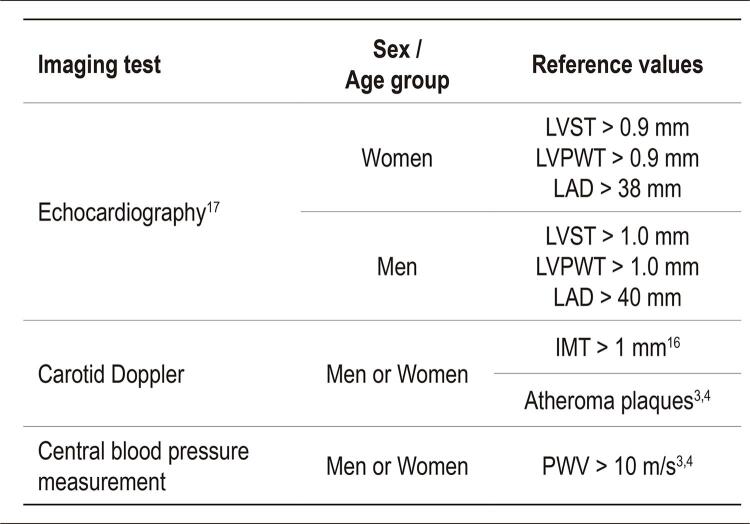

A identificação de LOA baseou-se na presença de EIM aumentada,17 placas de ateroma no Doppler de carótida,3 , 4 hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo (HVE) no ecocardiograma,18 e aumento da rigidez arterial identificado por uma VOP maior que 10m/s3 , 4 ( Figura 2 ).

Figura 2. – Exames e valores de referência considerados indicativos de lesões de órgãos-alvo. DAE: diâmetro do átrio esquerdo; EIM: espessura da íntima média; EPPVE: espessura da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo; ESVE: espessura do septo do ventrículo esquerdo; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso.

Análise Estatística

Os dados foram coletados e escaneados em duplicata por dois pesquisadores, utilizando o programa Epidata, versão 3.1. Após analisar e corrigir as inconsistências, os dados foram exportados para o programa Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), versão 18.0. O teste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov foi aplicado, e se realizou uma análise descritiva dos dados. A análise estatística foi realizada com base na distribuição dos dados, utilizando testes paramétricos e não paramétricos. Os dados numéricos foram descritos como média e desvio padrão ou média e intervalo interquartil, dependendo da distribuição dos dados. As variáveis categóricas foram apresentadas em frequência absoluta e relativa. O coeficiente de correlação de Pearson ou a correlação de Spearman foram usados para avaliar a correlação da VOP com os resultados obtidos no Doppler de carótida e ecocardiograma. As correlações foram classificadas como fraca (0 < r <0,30), moderada (0,30 ≤ r < 0,60), forte (0,60 ≤ r < 0,90) e muito forte (0,90 ≤ r < 1).19

A associação entre a VOP e outros biomarcadores (EIM, ESVE, EPPVE e DAE) foi avaliada por análise de regressão linear bivariada. As variáveis com p <0.020 foram usadas na análise de regressão múltipla. Todas as premissas para a aplicação da análise de regressão linear foram atendidas. A VOP foi comparada segundo magnitude da EIM, presença ou não de HVE, presença ou não de placa, dimensão da placa, e presença ou não de LOA, utilizando-se o teste para amostras independentes ou o teste de Mann-Whitney. Valores de p<0,05 foram considerados estatisticamente significativos.

Aspectos Éticos

O estudo foi conduzido de acordo com a resolução 466/12 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde, e foi aprovado pelo comitê de ética do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) (protocolo de aprovação número 1.500.463).

Resultados

Um total de 355 indivíduos, com idade média de 56,1 (±14,8) anos participaram no estudo. A maioria apresentou dislipidemia e/ou hipertensão arterial, 148 (41;7%) apresentavam sobrepeso e 130 (36.6%) eram obesos ( Tabela 1 ).

Tabela 1. – Características da amostra.

| Variáveis | Média (DP) / Mediana (25%-75%) / n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Idade | 56,1 (±14,8) | |

| IMC | 28,7 (±4,9) | |

| PASc | 113 (107-123) | |

| IA | 21,5 (±13,4) | |

| VOP | 8,2 (±2) | |

| Sexo | ||

| Masculino | 181 (51%) | |

| Feminino | 174 (49%) | |

| Estado civil | ||

| Com parceiro | 251 (70,7%) | |

| Sem parceiro | 102 (28,7%) | |

| Fatores de risco cardiovasculares | ||

| Sobrepeso | 148 (41.7%) | |

| Obesidade | 130 (36,6%) | |

| Tabagismo | 12 (3,4%) | |

| Diagnóstico | ||

| Dislipidemia | 306 (86,2%) | |

| Hipertensão arterial | 283 (79,7%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 65 (18.3%) | |

| Pré-hipertensão | 47 (13,2%) | |

IA: índice de aumento; IMC: índice de massa corporal; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso; PASc: pressão arterial sistólica central.

Uma correlação moderada e positiva foi encontrada entre a VOP e a EIM; e correlações positivas fracas foram identificadas entre a VOP e a ESVE, e entre a EPPVE e DAE) ( Tabela 2 ).

Tabela 2. – Correlação da velocidade de onda de pulso e biomarcadores cardiovasculares.

| EIM (n=178) | ESVE (n=313) | EPPVE (n=312) | DAE (n=312) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VOP | r | 0,310† | 0,191† | 0,215† | 0,181‡ |

| p | <0,001* | 0,001* | <0,001* | 0,001* |

*p < 0.05. †Correlação de Spearman; ‡Correlação de Pearson; EIM: espessura da íntima média; DAE: diâmetro do átrio esquerdo; EPPVE: espessura da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo; ESVE: espessura do septo ventricular esquerdo; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso.

A EIM foi associada com a VOP ajustada para idade e pressão sistólica periférica (p=0.0004). Um aumento de 1mm ou mais na EIM aumentou em 3.94 vezes a chance de se apresentar VOP acima de 10m/s ( Tabelas 3 e 4 ).

Tabela 3. – Análise de regressão linear bivariada da velocidade de onda de pulso com biomarcadores cardiovasculares.

| Variáveis | OR | IC95% (OR) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESVE | 2,49 | 1,38 – 4,49 | 0,003* |

| EIM | 3,94 | 1,53 – 10,15 | 0,004* |

| EPPVE | 2,34 | 1,29 – 4,22 | 0,005* |

| DAE | 2,55 | 1,18 – 5,49 | 0,017* |

IC: intervalo de confiança; EIM: espessura da íntima média; DAE: diâmetro do átrio esquerdo; EPPVE: espessura da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo; ESVE: espessura do septo ventricular esquerdo; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso; OR: odds ratio; * p < 0,05.

Tabela 4. – Análise de regressão múltipla da velocidade de onda de pulso com biomarcadores cardiovasculares.

| Variáveis | OR ajustado | IC 95% (OR) | p | OR ajustado* | IC 95% (OR) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVST | 1,64 | 0,59-4,5 | 0,340 | - | - | - |

| IMT | 3,94 | 1,53- 10,15 | 0,004 | 6,86 | 1,78-26,45 | <0,001 |

| LVPWT | 1,69 | 0,64-4,49 | 0,294 | - | - | - |

| LAD | 1,34 | 0,27-6,80 | 0,705 | - | - | - |

IC: intervalo de confiança; EIM: espessura da íntima média; DAE: diâmetro do átrio esquerdo; EPPVE: espessura da parede posterior do ventrículo esquerdo; ESVE: espessura do septo ventricular esquerdo; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso; OR: odds ratio; * p < 0,05.

A VOP foi significativamente maior em indivíduos com HVE, com EIM mais elevada, e indivíduos com placa de carótida, estenose igual ou maior que 50%, e com LOA ( Tabela 5 ).

Tabela 5. – Comparação da velocidade de onda de pulso de acordo com variáveis de Doppler de carótida e presença ou não de lesões de órgãos-alvo.

| Variável | Grupo | n | VOP | IC | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVE † | Não | 212 | 7,6 | 7,55 - 8,03 | <0,0001* |

| Sim | 105 | 9,1 | 8,74 – 9,53 | ||

| EIM ‡ | ≤ 1 mm | 152 | 8,07 | 7,79 - 8,35 | 0,006 |

| > 1 mm | 26 | 9,12 | 8,32 - 9,90 | ||

| Presença de placa ‡ | Não | 82 | 7,44 | 7,14 - 7,75 | <0,0001* |

| Sim | 172 | 9,09 | 8,83 - 9,35 | ||

| Tamanho da placa ‡ | < 50% | 146 | 8,92 | 8,64 - 9,20 | 0,003 |

| ≥ 50% | 25 | 10,0 | 9,42 - 10,63 | ||

| Lesões de órgãos-alvo** ,‡ | Não | 118 | 6,9 | 6,62 - 7,12 | <0,0001* |

| Sim | 237 | 8,9 | 8,69 - 9,17 |

IC: intervalo de confiança; EIM: espessura da íntima média; HVE: hipertrofia do ventrículo esquerdo; VOP: velocidade de onda de pulso; *p < 0,05. † Teste de Mann-Whitney. ‡ Teste t para amostras independentes. ** EIM>1mm, presença de placa, HVE ou VOP > 10 m/s.

Discussão

No presente estudo, a VOP correlacionou-se com todos os biomarcadores avaliados, e se associou com EIM, mesmo após ajuste para idade e pressão sistólica periférica. A chance de apresentar VOP acima de 10 m/s foi 3,94 vezes maior na presença de EIM maior que 1mm. A VOP apresentou um aumento linear com a presença e tamanho da placa de ateroma, e com a presença de LOA. Esses resultados estão de acordo com os de estudos publicados anteriormente,2 , 20 , 21 e reforçam o valor desse biomarcador e sua capacidade de identificar precocemente lesões cardiovasculares, além de seu excelente custo-benefício.

A correlação da VOP com parâmetros ecocardiográficos encontrada no presente estudo pode ser explicada pelo fato de que a rigidez arterial aumenta a PAS, o que causa um retorno precoce das ondas de pulso na sístole em vez de na diástole, e aumento da pós-carga do ventrículo esquerdo. Esse aumento de carga imposto sobre o miocárdio promove hipertrofia cardíaca, e consequente hipertrofia ventricular.22 - 24

A HVE, a qual pode ser identificada pelo aumento na espessura da parede do ventrículo esquerdo no ecocardiograma, correlaciona-se com a VOP, e valores de VOP são significativamente maiores em indivíduos com HVE.22 , 23 A sobrecarga sobre o ventrículo esquerdo é uma das principais causas de eventos cardiovasculares relacionados com a PAC.25

Muitos estudos apresentam não só uma correlação26 - 28 como também uma associação entre rigidez arterial e HVE.22 , 23 , 29 - 32 Portanto, a rigidez arterial aumentada pode ser usada como preditor de HVE, contribuindo para a prevenção e diagnóstico dessa condição.23

Em nosso estudo, não observamos uma associação independente da VOP com ESVE, EPPVE ou DAE, possivelmente por não termos realizado uma análise de associação entre hipertrofia e VOP como nos estudos citados, mas sim entre parâmetros ecocardiográficos e VOP. Ainda, em um dos estudos citados,22 foram utilizados achados eletrocardiográficos e não resultados ecocardiográficos, e a maioria dos estudos realizou essa análise de associação com base no índice da massa ventricular esquerda.23 , 28 , 30 , 32

A relação entre o aumento da rigidez arterial e o aumento da EIM pode ser explicada pela fisiopatologia da rigidez arterial, que engloba mudanças na matriz extracelular da camada média (túnica média), incluindo quebra de elastina, depósito de colágeno, e reticulação.24 , 33 Tais alterações morfológicas também estão relacionadas com envelhecimento vascular.34

Um aumento da EIM também está associado com a presença de fatores de risco para arteriosclerose; e idade, pressão arterial, lipídios séricos, e níveis de glicemia de jejum são todos preditores independentes de aterosclerose de carótida.35 EIM aumentada é uma das manifestações subclínicas da arteriosclerose.36 Existe uma associação independente entre a presença de múltiplos fatores de risco cardiovasculares com aumento na EIM e redução da complacência arterial.37

A correlação38 e a associação da EIM38 , 39 com a VOP também foram previamente relatadas na população idosa.

A avaliação da EIM e da VOP pode aumentar a reclassificação de risco, e esses biomarcadores podem ser utilizados na identificação de LOA.40 A combinação desses biomarcadores aumenta o poder preditivo de eventos cardiovasculares em idosos, fornecendo novas informações clínicas importantes.41

Em nosso estudo, valores significativamente maiores de VOP foram identificados em indivíduos com estenose igual ou maior que 50%. Valores mais elevados da VOP também se associaram significativamente com presença de placas de carótida.36 Além disso, uma redução na elasticidade da carótida está associada com presença de placas e risco de acidente vascular cerebral.42

A avaliação combinada de EIM e presença de placas melhora a predição de risco cardiovascular, e a avaliação quantitativa de placas aumenta ainda mais a sensibilidade preditiva.43Ainda, a VOP na carótida femoral e o número de placas de ateroma estão associados de maneira significativa e independente com morte cardiovascular, e pode melhorar a identificação de indivíduos em alto risco cardiovascular.44

Além das associações entre VOP e biomarcadores, a diferença significativa na VOP encontrada entre indivíduos com e sem LOA destaca a capacidade da VOP em detectar a lesão precocemente. A rigidez arterial é um preditor independente de mortalidade tanto para diabéticos como para a população em geral, e está relacionada com desenvolvimento e progressão de LOA.45

A rigidez arterial, avaliada pela VOP, associa-se independentemente com a presença de LOA subclínica, incluindo calcificação da artéria coronária, índice tornozelo-braquial reduzido (doença arterial periférica), e hiperintensidade da substância branca (doença arterial cerebral).46

Quando a LOA está presente, mas não é identificada, muitos pacientes são erroneamente classificados como em risco baixo a médio, quando na verdade estão em um risco cardiovascular alto.47

As ferramentas diagnósticas devem ser aprimoradas e estabelecidas para a identificação precoce de um risco aumentado, para prevenir o início de LOA e suas complicações. A identificação apropriada de indivíduos com baixo risco é igualmente importante para evitar tratamentos desnecessários e seus efeitos colaterais.48 O uso de biomarcadores vasculares é um método custo-efetivo, com valor agregado, na melhoria da identificação de indivíduos em alto risco, facilitando, assim, a prevenção de DCV.44

As limitações deste estudo incluem: (1) quando o diagnóstico de diabetes mellitus, dislipidemia e hipertensão arterial não estava disponível nos prontuários médicos, o diagnóstico foi feito durante o estudo, de maneira ad hoc , o que pode ter subestimado ou superestimado as frequências dessas doenças. (2) Algumas variáveis de exposição também estavam ausentes nos prontuários médicos. (3) Ainda, não podemos assegurar que todos os pacientes foram submetidos ao Doppler e à ecocardiografia no mesmo local e com o mesmo avaliador. Hipertrofia não pode ser detectada pelo índice da massa ventricular, uma vez que essa informação também não estava disponível nos prontuários.

Os prontuários médicos e os critérios diagnósticos foram avaliados com rigor científico, e os dados foram revisados por dois pesquisadores, com verificação cruzada. Todos esses procedimentos devem validar nossos achados.

O presente estudo destaca a importância do uso da VOP para a detecção precoce de rigidez arterial e LOA, com foco no aumento da EIM, presença de placas de carótida, e HVE. Em geral, a VOP pode otimizar a estratificação do risco cardiovascular para facilitar a intervenção precoce e prevenir DCV e suas complicações.

Conclusões

A VOP correlacionou-se significativamente com a EIM e com parâmetros ecocardiográficos, e se associou com a EIM. Uma EIM maior que 1mm aumentou a chance de se apresentar uma VOP maior que 10m/s em 3,94 vezes. A VOP foi maior nos indivíduos com HVE, EIM maior que 1mm, com estenose igual ou maior que 50%, e pacientes com LOA.

Vinculação Acadêmica

Este artigo é parte de dissertação de Mestrado de Rayne Ramos Fagundes pela Universidade Federal de Goiás.

Fontes de Financiamento .O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.. Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol.2017;70(1):1-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2017;70(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.. Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Aboyans V, Brodmann M, Cífková R, Cosentino F, et al. The role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary prevention. A position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripheral circulation. Endorsed by the Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology (ARTERY) Society. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241(2):507-32. [DOI] [PubMed]; Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Aboyans V, Brodmann M, Cífková R, Cosentino F, et al. The role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary prevention. A position paper from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on peripheral circulation. Endorsed by the Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology (ARTERY) Society. Atherosclerosis . 2015;241(2):507–532. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(28):2159-219. [DOI] [PubMed]; Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J . 2013;34(28):2159–2219. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.. Malachias MVB, Souza WKSB, Plavnik FL, Rodrigues CIS, Brandão AA, Neves MFT, et al. 7ª Diretriz Brasileira de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;107(Supl 3):1-83.; Malachias MVB, Souza WKSB, Plavnik FL, Rodrigues CIS, Brandão AA, Neves MFT, et al. 7ª Diretriz Brasileira de Hipertensão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol . 2016;107(Supl 3):1–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.. Mitchell GF. Does Measurement of Central Blood Pressure have Treatment Consequences in the Clinical Praxis? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(8):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Mitchell GF. Does Measurement of Central Blood Pressure have Treatment Consequences in the Clinical Praxis? Curr Hypertens Rep . 2015;17(8):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11906-015-0573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(13):1318-27. [DOI] [PubMed]; Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2010;55(13):1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.. The Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness’ Collaboration. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J. 2010;35(11):1367-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; The Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness’ Collaboration Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J . 2010;35(11):1367–1372. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.. Díaz A, Galli C, Tringler M, Ramírez A, Cabrera Fischer EI. Reference Values of Pulse Wave Velocity in Healthy People from an Urban and Rural Argentinean Population. Int J Hypertens. 2014;2014,653239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Díaz A, Galli C, Tringler M, Ramírez A, Cabrera Fischer EI. Reference Values of Pulse Wave Velocity in Healthy People from an Urban and Rural Argentinean Population. 653239 Int J Hypertens . 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/653239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.. Jatoi NA, Mahmud A, Bennett K, Feely J. Assessment of arterial stiffness in hypertension: comparison of oscillometric (Arteriograph), piezoelectronic (Complior) and tonometric (SphygmoCor) techniques. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2186-91. [DOI] [PubMed]; Jatoi NA, Mahmud A, Bennett K, Feely J. Assessment of arterial stiffness in hypertension: comparison of oscillometric (Arteriograph), piezoelectronic (Complior) and tonometric (SphygmoCor) techniques. J Hypertens . 2009;27(11):2186–2191. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833057e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.. Hametner B, Wassertheurer S, Kropf J, Mayer C, Eber B, Weber T. Oscillometric estimation of aortic pulse wave velocity: comparison with intra-aortic catheter measurements. Blood Press Monit. 2013;18(3):173-6. [DOI] [PubMed]; Hametner B, Wassertheurer S, Kropf J, Mayer C, Eber B, Weber T. Oscillometric estimation of aortic pulse wave velocity: comparison with intra-aortic catheter measurements. Blood Press Monit . 2013;18(3):173–176. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283614168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.. Quelet A. Antropométrie ou mesure des différentes facultés de l’homme. . Bruxelles: C. Muquardt; 1870.; Quelet A. Antropométrie ou mesure des différentes facultés de l’homme . Bruxelles: C. Muquardt; 1870. [Google Scholar]

- 12.. World Health Organization. (WHO). Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry Geneva;1995. [PubMed]; World Health Organization. WHO . Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry . Geneva: 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.. Wei W, Tolle M, Zidek W, van der Giet M. Validation of the mobil-O-Graph: 24 h-blood pressure measurement device. Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(4):225-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Wei W, Tolle M, Zidek W, van der Giet M. Validation of the mobil-O-Graph: 24 h-blood pressure measurement device. Blood Press Monit . 2010;15(4):225–228. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328338892f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.. Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, et al. Use of Carotid Ultrasound to Identify Subclinical Vascular Disease and Evaluate Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Consensus Statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine.J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008 2008;21(2):93-111. [DOI] [PubMed]; Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, et al. Use of Carotid Ultrasound to Identify Subclinical Vascular Disease and Evaluate Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Consensus Statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr . 2008;21(2):93–111. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.. Oates CP, Naylor AR, Hartshorne T, Charles SM, Fail T, Humphries K, et al. Joint Recommendations for Reporting Carotid Ultrasound Investigations in the United Kingdom. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37(3):251-61. [DOI] [PubMed]; Oates CP, Naylor AR, Hartshorne T, Charles SM, Fail T, Humphries K, et al. Joint Recommendations for Reporting Carotid Ultrasound Investigations in the United Kingdom. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg . 2009;37(3):251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1-39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed]; Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr . 2015;28(1):1–39. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.. Freire CMV, Alcantara ML, Santos SN, Amaral SI, Veloso O, Porto CLL, et al. Recomendação para a Quantificação pelo Ultrassom da Doença Aterosclerótica das Artérias Carótidas e Vertebrais: Grupo de Trabalho do Departamento de Imagem Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia – DIC -ABC Imag Cardiovasc,2015;28(especial):1-64.; Freire CMV, Alcantara ML, Santos SN, Amaral SI, Veloso O, Porto CLL, et al. Recomendação para a Quantificação pelo Ultrassom da Doença Aterosclerótica das Artérias Carótidas e Vertebrais: Grupo de Trabalho do Departamento de Imagem Cardiovascular da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia – DIC. ABC Imag Cardiovasc . 2015;28(especial):1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.. Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. United States: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.; Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine . United States: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.. Lira SA. Análise de correlação: Abordagem teórica de construção dos coeficientes com aplicações [tese]. Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2004.; Lira SA. Análise de correlação: Abordagem teórica de construção dos coeficientes com aplicações . Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2004. tese. [Google Scholar]

- 20.. Viola J, Soehnlein O. Atherosclerosis - A matter of unresolved inflammation. Semin Immunol. 2015;27(3):184-93. [DOI] [PubMed]; Viola J, Soehnlein O. Atherosclerosis - A matter of unresolved inflammation. Semin Immunol . 2015;27(3):184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.. Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Karafillis I, Nilsson P. Early vascular aging and the role of central blood pressure.J Hypertens. 2011;29(10):1847-53. [DOI] [PubMed]; Kotsis V, Stabouli S, Karafillis I, Nilsson P. Early vascular aging and the role of central blood pressure. J Hypertens . 2011;29(10):1847–1853. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834a4d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.. Chung CM, Lin YS, Chu CM, Chang ST, Cheng HW, Yang TY, et al. Arterial stiffness is the independent factor of left ventricular hypertrophy determined by electrocardiogram. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344(3):190-3. [DOI] [PubMed]; Chung CM, Lin YS, Chu CM, Chang ST, Cheng HW, Yang TY, et al. Arterial stiffness is the independent factor of left ventricular hypertrophy determined by electrocardiogram. Am J Med Sci . 2012;344(3):190–193. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318242a354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.. Yucel C, Demir S, Demir M, Tufenk M, Nas K, Molnar F, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and arterial stiffness in essential hypertension. Bratis Lek Listy. 2015;116(12):714-8. [DOI] [PubMed]; Yucel C, Demir S, Demir M, Tufenk M, Nas K, Molnar F, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and arterial stiffness in essential hypertension. Bratis Lek Listy . 2015;116(12):714–718. doi: 10.4149/bll_2015_140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.. Townsend RR, Wilkinson IB, Schiffrin EL, Avolio AP, Chirinos JA, Cockcroft JR, et al. Recommendations for Improving and Standardizing Vascular Research on Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension. 2015;66(3):698-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Townsend RR, Wilkinson IB, Schiffrin EL, Avolio AP, Chirinos JA, Cockcroft JR, et al. Recommendations for Improving and Standardizing Vascular Research on Arterial Stiffness. Hypertension . 2015;66(3):698–722. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.. Sabovic M, Safar ME, Blacher J. Is there any additional prognostic value of central blood pressure wave forms beyond peripheral blood pressure? Curr Pharmac Design. 2009;15(3):254-66. [DOI] [PubMed]; Sabovic M, Safar ME, Blacher J. Is there any additional prognostic value of central blood pressure wave forms beyond peripheral blood pressure? Curr Pharmac Design . 2009;15(3):254–266. doi: 10.2174/138161209787354249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.. Pizzi O, Brandão AA, Magalhães MEC, Pozzan R, Brandão AP. Velocidade de onda de pulso – o método e suas implicações prognósticas na hipertensão arterial. RevBras Hipertens. 2006;13(1):59-62.; Pizzi O, Brandão AA, Magalhães MEC, Pozzan R, Brandão AP. Velocidade de onda de pulso – o método e suas implicações prognósticas na hipertensão arterial. RevBras Hipertens . 2006;13(1):59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 27.. Su HM, Lin TH, Hsu PC, Lee CS, Lee WH, Chen SC, et al. Association of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, ankle-brachial index and ratio of brachial pre-ejection period to ejection time with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(4):289-94. [DOI] [PubMed]; Su HM, Lin TH, Hsu PC, Lee CS, Lee WH, Chen SC, et al. Association of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, ankle-brachial index and ratio of brachial pre-ejection period to ejection time with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Med Sci . 2014;347(4):289–294. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31828c5bee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.. Rabkin SW, Chan SH. Correlation of pulse wave velocity with left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension once blood pressure has been normalized. Heart Int. 2012;7(1):27-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Rabkin SW, Chan SH. Correlation of pulse wave velocity with left ventricular mass in patients with hypertension once blood pressure has been normalized. Heart Int . 2012;7(1):27–31. doi: 10.4081/hi.2012.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.. Bello H, Norton GR, Ballim I, Libhaber CD, Sareli P, Woodiwiss AJ. Contributions of aortic pulse wave velocity and backward wave pressure to variations in left ventricular mass are independent of each other. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11(5):265-74. [DOI] [PubMed]; Bello H, Norton GR, Ballim I, Libhaber CD, Sareli P, Woodiwiss AJ. Contributions of aortic pulse wave velocity and backward wave pressure to variations in left ventricular mass are independent of each other. J Am Soc Hypertens . 2017;11(5):265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.. Masugata H, Senda S, Hoshikawa J, Murao K, Hosomi N, Okuyama H, et al. Elevated brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients after stroke. Tohoku J Exper Med. 2010;220(3):177-82. [DOI] [PubMed]; Masugata H, Senda S, Hoshikawa J, Murao K, Hosomi N, Okuyama H, et al. Elevated brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients after stroke. Tohoku J Exper Med . 2010;220(3):177–182. doi: 10.1620/tjem.220.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.. Park KH, Park WJ, Kim MK, Jung JH, Choi S, Cho JR, et al. Noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(3):269-74. [DOI] [PubMed]; Park KH, Park WJ, Kim MK, Jung JH, Choi S, Cho JR, et al. Noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Hypertens . 2010;23(3):269–274. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.. Nitta K, Akiba T, Uchida K, Otsubo S, Otsubo Y, Takei T, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res. 2004;27(1):47-52. [DOI] [PubMed]; Nitta K, Akiba T, Uchida K, Otsubo S, Otsubo Y, Takei T, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res . 2004;27(1):47–52. doi: 10.1291/hypres.27.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.. Palombo C, Kozakova M. Arterial stiffness, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiologic mechanisms and emerging clinical indications. Vasc Pharmacol. 2016;77:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed]; Palombo C, Kozakova M. Arterial stiffness, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiologic mechanisms and emerging clinical indications. Vasc Pharmacol . 2016;77:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2015.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.. Costantino S, Paneni F, Cosentino F. Ageing, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2016;594(8):2061-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Costantino S, Paneni F, Cosentino F. Ageing, metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol . 2016;594(8):2061–2073. doi: 10.1113/JP270538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.. Ren L, Cai J, Liang J, Li W, Sun Z. Impact of Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Degree of Severity: A Cross-Sectional Study. PloS one. 2015;10(12):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Ren L, Cai J, Liang J, Li W, Sun Z. Impact of Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Degree of Severity: A Cross-Sectional Study. PloS one . 2015;10(12):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.. Selwaness M, van den Bouwhuijsen Q, Mattace-Raso FU, Verwoert GC, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Arterial stiffness is associated with carotid intraplaque hemorrhage in the general population: the Rotterdam study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34(4):927-32. [DOI] [PubMed]; Selwaness M, van den Bouwhuijsen Q, Mattace-Raso FU, Verwoert GC, Hofman A, Franco OH, et al. Arterial stiffness is associated with carotid intraplaque hemorrhage in the general population: the Rotterdam study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol . 2014;34(4):927–932. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.. Niu L, Zhang Y, Qian M, Meng L, Xiao Y, Wang Y, et al. Impact of multiple cardiovascular risk factors on carotid intima-media thickness and elasticity. PloS one. 2013;8(7):1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Niu L, Zhang Y, Qian M, Meng L, Xiao Y, Wang Y, et al. Impact of multiple cardiovascular risk factors on carotid intima-media thickness and elasticity. PloS one . 2013;8(7):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.. Costa LS, Cunha JVL, Tress JC, Pozzan R, Neto CD, Brandão AP. A importância das medidas de pressão arterial e da velocidade da onda de pulso no desenvolvimento da hipertrofia ventricular esquerda e no espessamento médio-intimal de carótidas em pacientes idosos. Revista da SOCERJ. 2005;18(2):160-71.; Costa LS, Cunha JVL, Tress JC, Pozzan R, Neto CD, Brandão AP. A importância das medidas de pressão arterial e da velocidade da onda de pulso no desenvolvimento da hipertrofia ventricular esquerda e no espessamento médio-intimal de carótidas em pacientes idosos. Revista da SOCERJ . 2005;18(2):160–171. [Google Scholar]

- 39.. van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, et al. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke. 2001;32(2):454-60. [DOI] [PubMed]; van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML, Asmar R, Topouchian J, Reneman RS, et al. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke . 2001;32(2):454–460. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.. Bruno RM, Bianchini E, Faita F, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L. Intima media thickness, pulse wave velocity, and flow mediated dilation. Ultrassom Cardiovsc 2014;12:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Bruno RM, Bianchini E, Faita F, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L. Intima media thickness, pulse wave velocity, and flow mediated dilation. 34 Ultrassom Cardiovsc . 2014;12 doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.. Nagai K, Shibata S, Akishita M, Sudoh N, Obara T, Toba K, et al. Efficacy of combined use of three non-invasive atherosclerosis tests to predict vascular events in the elderly; carotid intima-media thickness, flow-mediated dilation of brachial artery and pulse wave velocity. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(2):365-70. [DOI] [PubMed]; Nagai K, Shibata S, Akishita M, Sudoh N, Obara T, Toba K, et al. Efficacy of combined use of three non-invasive atherosclerosis tests to predict vascular events in the elderly; carotid intima-media thickness, flow-mediated dilation of brachial artery and pulse wave velocity. Atherosclerosis . 2013;231(2):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.. Boesen ME, Singh D, Menon BK, Frayne R. A systematic literature review of the effect of carotid atherosclerosis on local vessel stiffness and elasticity. Atherosclerosis. 2015;243(1):211-22. [DOI] [PubMed]; Boesen ME, Singh D, Menon BK, Frayne R. A systematic literature review of the effect of carotid atherosclerosis on local vessel stiffness and elasticity. Atherosclerosis . 2015;243(1):211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.. Naqvi TZ, Lee MS. Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque in cardiovascular risk assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Imag. 2014;7(10):1025-38. [DOI] [PubMed]; Naqvi TZ, Lee MS. Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque in cardiovascular risk assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Imag . 2014;7(10):1025–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.. Berard E, Bongard V, Ruidavets JB, Amar J, Ferrieres J. Pulse wave velocity, pulse pressure and number of carotid or femoral plaques improve prediction of cardiovascular death in a population at low risk. J Humman Hypertens. 2013;27(9):529-34. [DOI] [PubMed]; Berard E, Bongard V, Ruidavets JB, Amar J, Ferrieres J. Pulse wave velocity, pulse pressure and number of carotid or femoral plaques improve prediction of cardiovascular death in a population at low risk. J Humman Hypertens . 2013;27(9):529–534. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2013.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.. Prenner SB, Chirinos JA. Arterial stiffness in diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238(2):370-9. [DOI] [PubMed]; Prenner SB, Chirinos JA. Arterial stiffness in diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis . 2015;238(2):370–379. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.. Coutinho T, Turner ST, Kullo IJ. Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Is Associated With Measures of Subclinical Target Organ Damage. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2011;4(7):754-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Coutinho T, Turner ST, Kullo IJ. Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Is Associated With Measures of Subclinical Target Organ Damage. JACC Cardiovascular imaging . 2011;4(7):754–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.. Piskorz D, Bongarzoni L, Citta L, Citta N, Citta P, Keller L, et al. World Health Organization cardiovascular risk stratification and target organ damage. Hipertens. riesgo vasc. 2016;33(1):14-20. [DOI] [PubMed]; Piskorz D, Bongarzoni L, Citta L, Citta N, Citta P, Keller L, et al. World Health Organization cardiovascular risk stratification and target organ damage. Hipertens. riesgo vasc . 2016;33(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.hipert.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.. Øygarden H. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease. Am Heart J. 2017;6(1):1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Øygarden H. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease. Am Heart J . 2017;6(1):1–3. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]