Abstract

The GE81112 complex has garnered much interest due to its broad antimicrobial properties and unique ability to inhibit bacterial translation initiation. Herein we report the use of a chemoenzymatic strategy to complete the first total synthesis of GE81112 B1. By pairing iron- and α-ketoglutarate dependent hydroxylases found in GE81112 biosynthesis with traditional synthetic methodology, we were able to access the natural product in 11 steps (longest linear sequence). Following this strategy, ten GE81112 B1 analogs were synthesized, allowing for identification of its key pharmacophores. A key feature of our medicinal chemistry effort is the incorporation of additional biocatalytic hydroxylations in modular analog synthesis to rapidly enable exploration of relevant chemical space.

Introduction

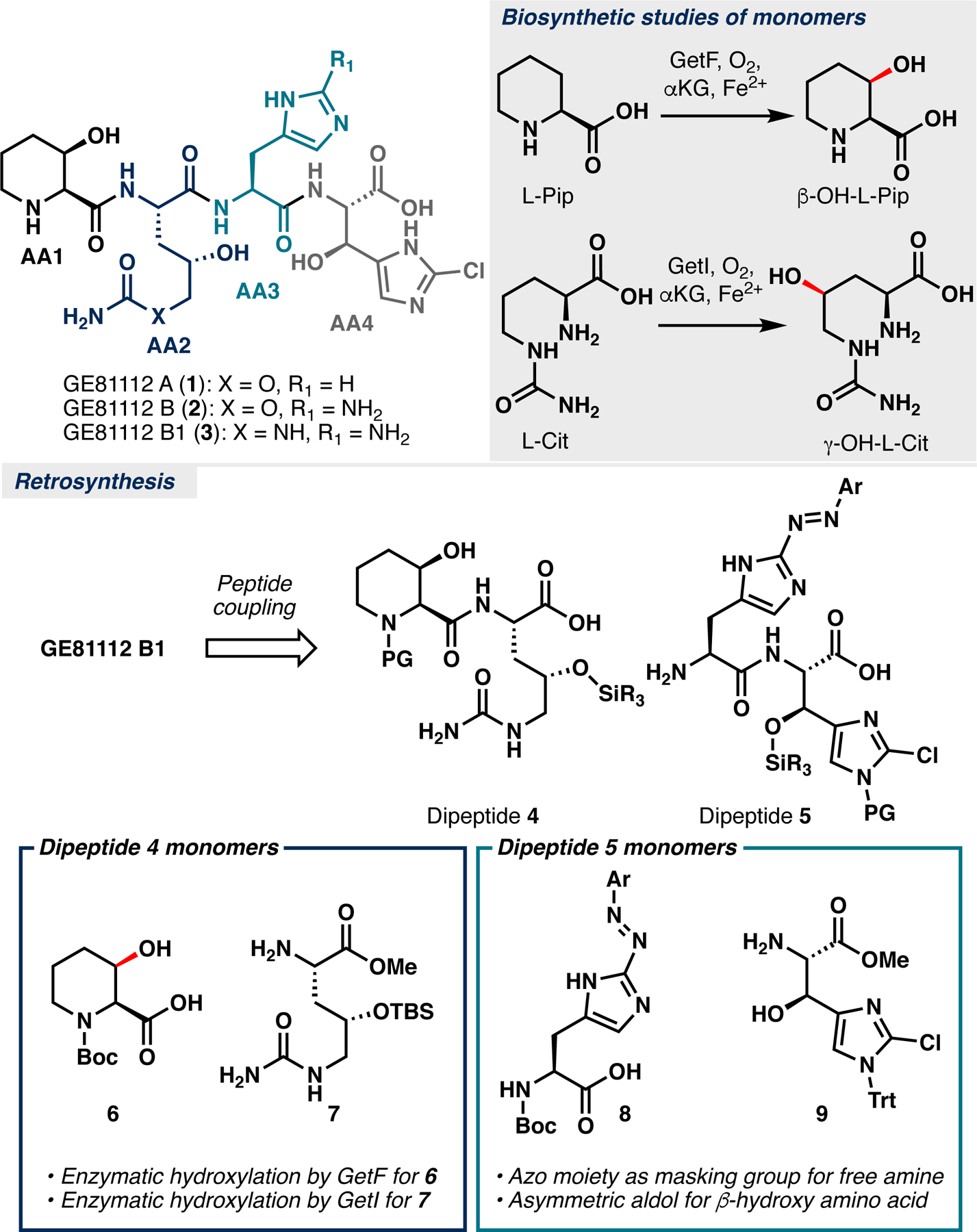

GE81112 is a complex of three related tetrapeptides identified in 2006 during a screen for new inhibitors of bacterial protein synthesis (Figure 1A).1 Structurally, GE81112 consists of several unusual amino acids, including 3-hydroxy-L-pipecolic acid (AA1), 4-hydroxy-L-citrulline or O-carbamoyl-2-amino-dihydroxyvaleric acid (AA2), 2-amino-L-histidine (AA3) and β-hydroxy-2-chloro-L-histidine (AA4). Each GE81112 tetrapeptide demonstrates broad antimicrobial properties conveyed by a unique mechanism of action: inhibition of bacterial translation initiation.1 Subsequent studies have confirmed that GE81112 binds to the 30S ribosome, inhibiting the P-site decoding of an mRNA’s initiation codon by fMet-tRNA’s anticodon.2 Although GE81112 displays broad-spectrum activity in minimal media, its activity is significantly attenuated against bacteria grown in rich media.1 Subsequent mechanistic studies indicate that illicit transport of GE81112 into its bacterial target is mediated by peptidyl transporter oligopeptide permease (Opp), but competition with peptides found in rich media results in reduced efficacy.3 Based on these findings, development of GE81112 analogs that can permeate the bacterial cell membrane without the aid of Opp presents a potential solution. To date, there is only one reported total synthesis of the GE81112s (GE81112 A, 2018) though minimal structure-activity relationship (SAR) has been established for this tetrapeptide.4 Additionally, the reported synthesis suffers from high step-count (7–8 steps per fragment) and poor stereocontrol (Figure 1A). In light of these shortcomings, we sought to develop a tractable chemoenzymatic synthesis of GE81112 B1 that will also be amenable for analog generation for SAR analysis.

Figure 1.

Structures of the GE81112 tetrapeptide complex. A. Known biosynthesis of its monomers. B. Our retrosynthetic analysis of GE81112 B1 (3).

Results and Discussion

Our synthetic design combines biocatalytic and contemporary chemical approaches to construct each fragment with minimal step count.5 To balance these synthetic paradigms, we devised a biocatalytic approach for the preparation of AA1 & AA2, and traditional chemical approach for AA3 & AA4. We envisioned utilizing C–H hydroxylation reactions present in GE81112 biosynthesis to construct AA1 & AA2 (Figure 1B). Previous reports established GetF and GetI as iron- and α-ketoglutarate dependent dioxygenase enzymes (Fe/αKG) responsible for hydroxylation of L-pipecolic acid (L-Pip) and L-citrulline (L-Cit), respectively (Figure 1B).6 Next, a chemoselective azo coupling would establish a “masked” 2-aminoimidazole motif present within AA3, aiding purification and imparting chemoselectivity in subsequent transformations.7 An asymmetric aldol transform would establish AA4 while also controlling the syn-1,2-amino alcohol stereochemistry. Convergent assembly of each fragment, followed by protecting group removal would afford GE81112 B1. This strategy was also designed with modularity in mind, as further analogs of GE81112 B1 could be prepared by tapping into the wealth of sequence diversity of Fe/αKG hydroxylases for preparing alternative AA1 and AA2 units and using alternative aldehyde partners for preparing alternative AA4 units. While seemingly straightforward, successful implementation of our strategy would still require careful choreography of protecting group manipulations and condition selections to avoid chemoselectivity issues. For example, late-stage hydrogenative unmasking of the 2-azoimidazole functionality in the presence of reduction-prone 2-chloro-imidazole could present a major concern. Here, we rationalized that introduction of a suitable protecting group on the 2-chloroimidazole unit would allow for chemoselective azo hydrogenation based on differing steric environments.

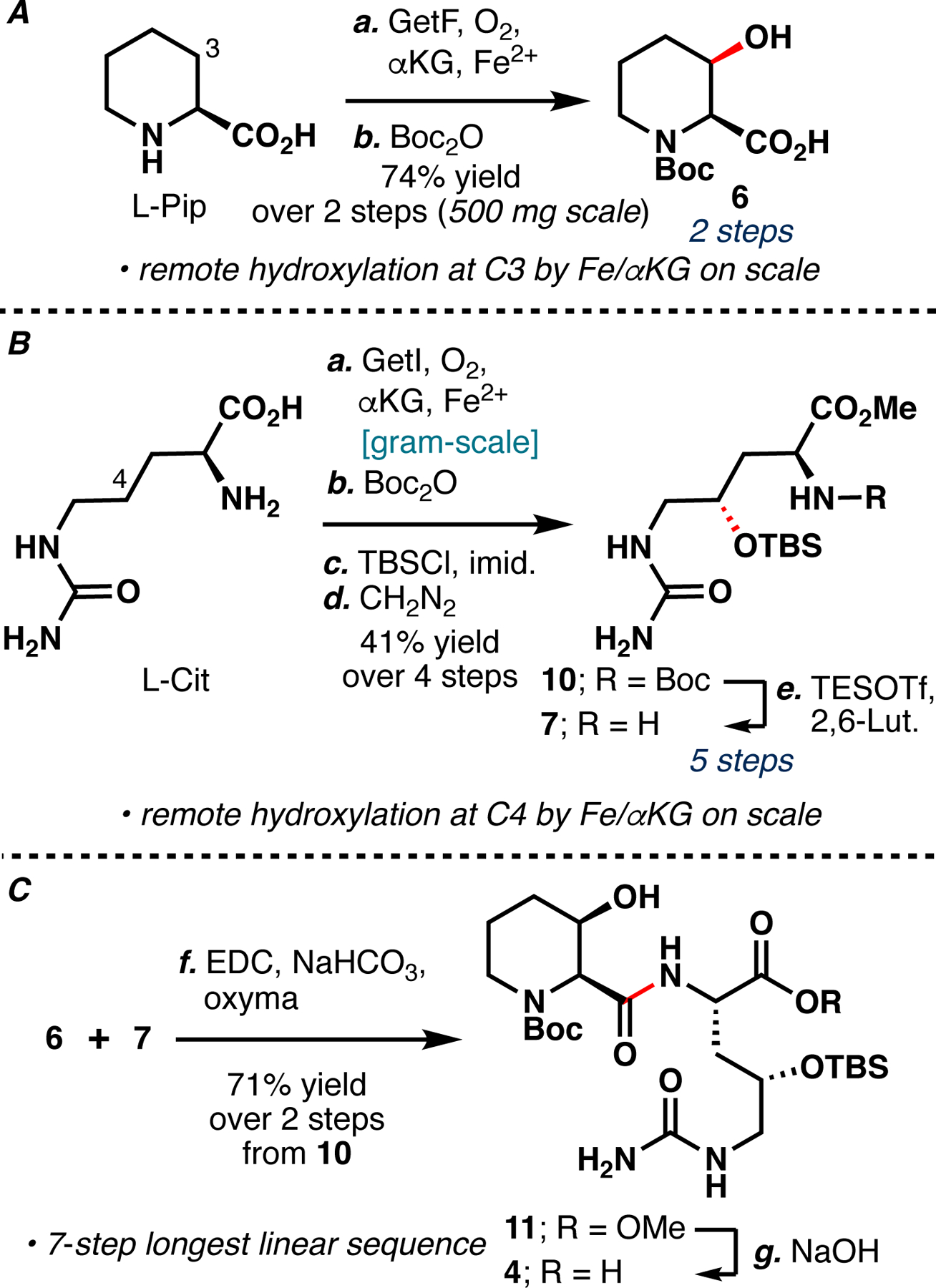

We first sought to establish GetF and GetI as robust biocatalysts for the preparation of monomers AA1 and AA2. GetF was recently used to hydroxylate 3-methylproline in the synthesis of 3-hydroxy-3-methylproline, although a large-scale reaction with L-Pip has not been reported.8 GetF was initially found to suffer from poor soluble expression when expressed as N-His6-tagged protein, but co-expression of chaperones GroES/GroEL resulted in a dramatic improvement in soluble enzyme expression.8,9 For large-scale reactions, L-Pip was combined with αKG, FeSO4, ascorbic acid (asc) and lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3) co-expressing GetF and GroES/GroEL chaperone proteins. Complete conversion on 500 mg scale was possible utilizing 20 mM substrate concentration, pH=8 kPi buffer and clarified lysate (Scheme 1A, Table SI1). Following ion-exchange purification, the resulting crude material was converted to the corresponding N-Boc derivative, affording 6 in 74% yield over two steps (Scheme 1A). Similarly, L-Cit was combined with αKG, FeSO4, asc and lysate of E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing GetI. Optimization of lysis conditions and head-space volume proved vital for obtaining complete conversion consistently on gram scale with 20 mM substrate concentration (Table SI2). Ion-exchange purification, Boc and TBS protections, followed by methyl esterification resulted in a 41% yield of 10 over four steps (Scheme 1B). Due to the acid labile nature of the 2° TBS group, removal of the Boc group necessitated the use of TESOTf buffered by 2,6-lutidine.10a,b These conditions presumably proceed through the intermediacy of a silyl carbamate, which is hydrolyzed upon work-up. The resulting amine 7 was carried on crude to peptide coupling with 6, yielding 4 after saponification (Scheme 1C).

Scheme 1.

A. GetF catalyzed hydroxylation of L-Pip and subsequent Boc protection. B. GetI catalyzed hydroxylation of L-Cit and subsequent protecting group manipulations. C. Peptide coupling between 6 and 7 followed by saponification.

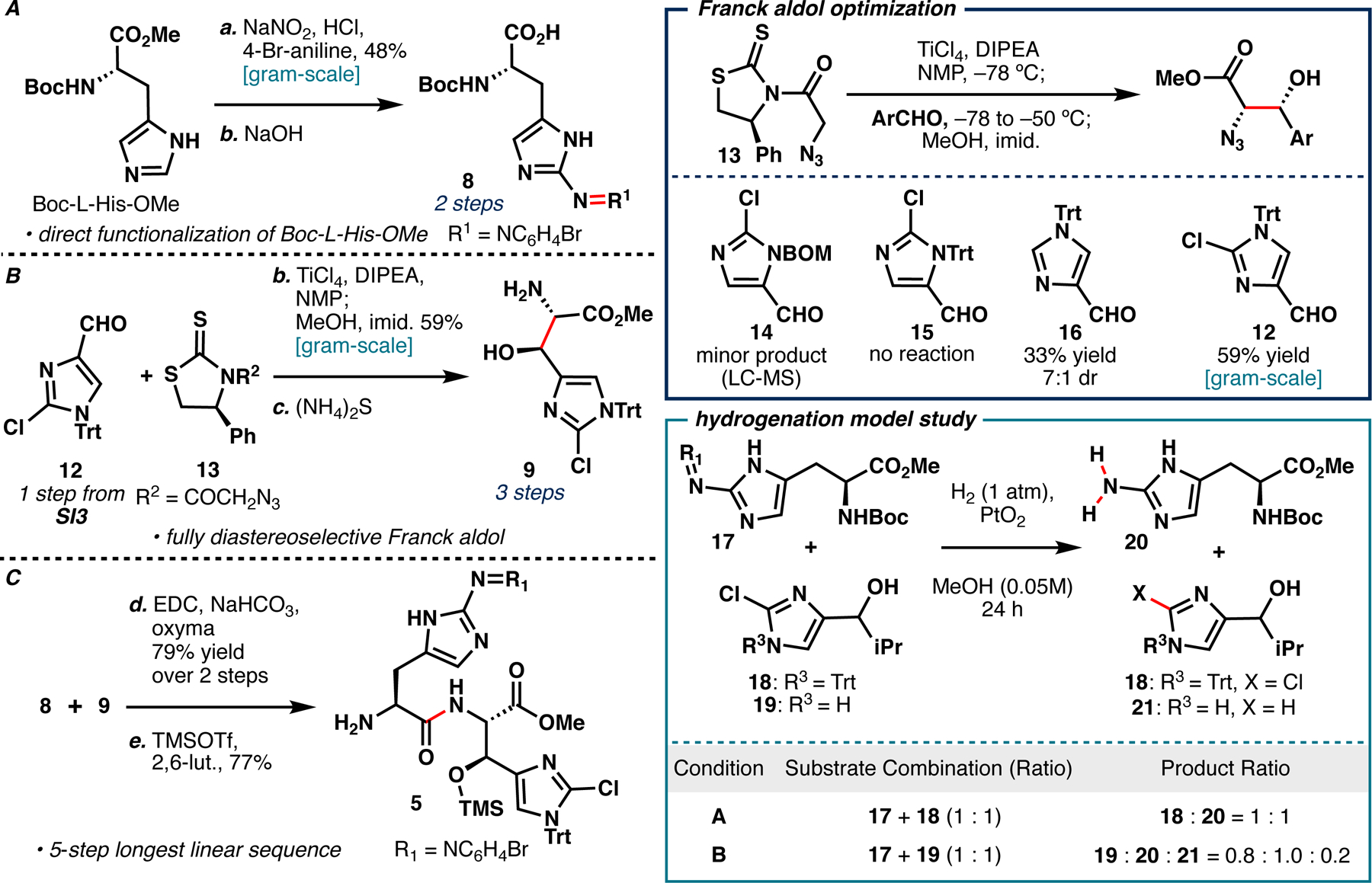

With access to 4, construction of dipeptide 5 could now commence (Scheme 2). Initially, we tested previously reported conditions for 2-azotisation of Boc-His-OMe (HCl, NaNO2, pH=10.5 Na2B4O7 buffer, 4-aminobenzoate, 65%), which unfortunately gave 6% yield in our hands.7 After testing a variety of azo coupling conditions (Table SI3), we eventually discovered that modulating the initially tested conditions by switching the coupling partner (4-aminobenzoate to 4-bromoaniline) gave 48% yield of our desired 2-azoimidazole (Scheme 2A). Saponification of the methyl ester gave acid 8, which was used crude in subsequent peptide coupling. To construct AA4, we initially attempted Myers’ asymmetric aldol using pseudophenamine glycinamide as a chiral auxiliary, but the resulting aldol adduct proved unstable to purification or subsequent transformations; in-line with their previous report.11 As an alternative, we investigated TiCl4-mediated aldol conditions previously reported by Franck for the synthesis of syn-1,2-azido-alcohols from azidoacetyl-4-phenylthiazolidin-2-thione (13, Scheme 2B).12 To our dismay, 2-chloro-5-formyl-BOM-imidazole (14) showed only minor product by LC-MS analysis, and no observable product upon work-up (Scheme 2, blue inset). Switching the BOM protecting group to Trt (15) showed no reaction by LC/MS or NMR. Based on these findings, we speculated that increased steric congestion proximal to the aldehyde might block the titanium enolate’s approach. In line with this hypothesis, 4-formyl-Trt-imidazole (16), which places the Trt protecting group distal to the aldehyde gave 7:1 dr and 33% isolated yield after methanolysis. The use of 2-chloro-4-formyl-Trt-imidazole (12, accessible from known SI4 in one step) in the reaction gave the syn-1,2-azido-alcohol product in 59% yield as a single diastereomer on gram-scale. Subsequently, azide reduction proved non-trivial, resulting in trityl deprotection, chloride reduction, or non-specific degradation under the conditions tested (Table SI4). A report by Boger used gaseous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) for azide reduction in the preparation of related histidine analogs.13 As hydrogen sulfide is toxic and not widely available, we instead tried aqueous ammonium sulfide ((NH4)2S), which very cleanly yielded the desired amino alcohol 9 without the need for subsequent purification (Table SI4, entry 9).14 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported use of these conditions for the reduction of alkyl azides.

Scheme 2.

A. Azo coupling on Boc-L-His-OMe to prepare the masked 2-aminohistidine motif and subsequent hydrolysis. B. Diastereoselective synthesis of 9 via Franck aldol between 12 and 13 followed by azide reduction. C. Synthesis of key dipeptide 5 by peptide coupling between 8 and 9 followed by Boc deprotection. Blue inset: substrate preference of Franck aldol with 13. Teal inset: Model study for chemoselective reduction of the 2-azoimidazole moiety.

Since late-stage chloride reduction was of concern, we designed a model system to probe the viability of performing a chemoselective 2-azoimidazole hydrogenation in the presence of a 2-chloroimidazole-containing molecule (Scheme 2, teal inset). Submitting an equimolar ratio of 17 and AA4 surrogate 18 to reaction with H2 and PtO2 gratifyingly yielded chemoselective azo hydrogenation.7 To confirm that chemoselectivity was imparted by the Trt, we also submitted an equimolar ratio of 17 and des-Trt-alcohol 19 to the same hydrogenation conditions, which gave a 4:1 mixture of 19 to des-chloro 21. These observations suggest that Trt protection imparts chemoselectivity between the azo and chloro functionality and that control of the steric environment around the 2-chloroimidazole would allow for late-stage removal of the azo functionality en route to GE81112 B1.

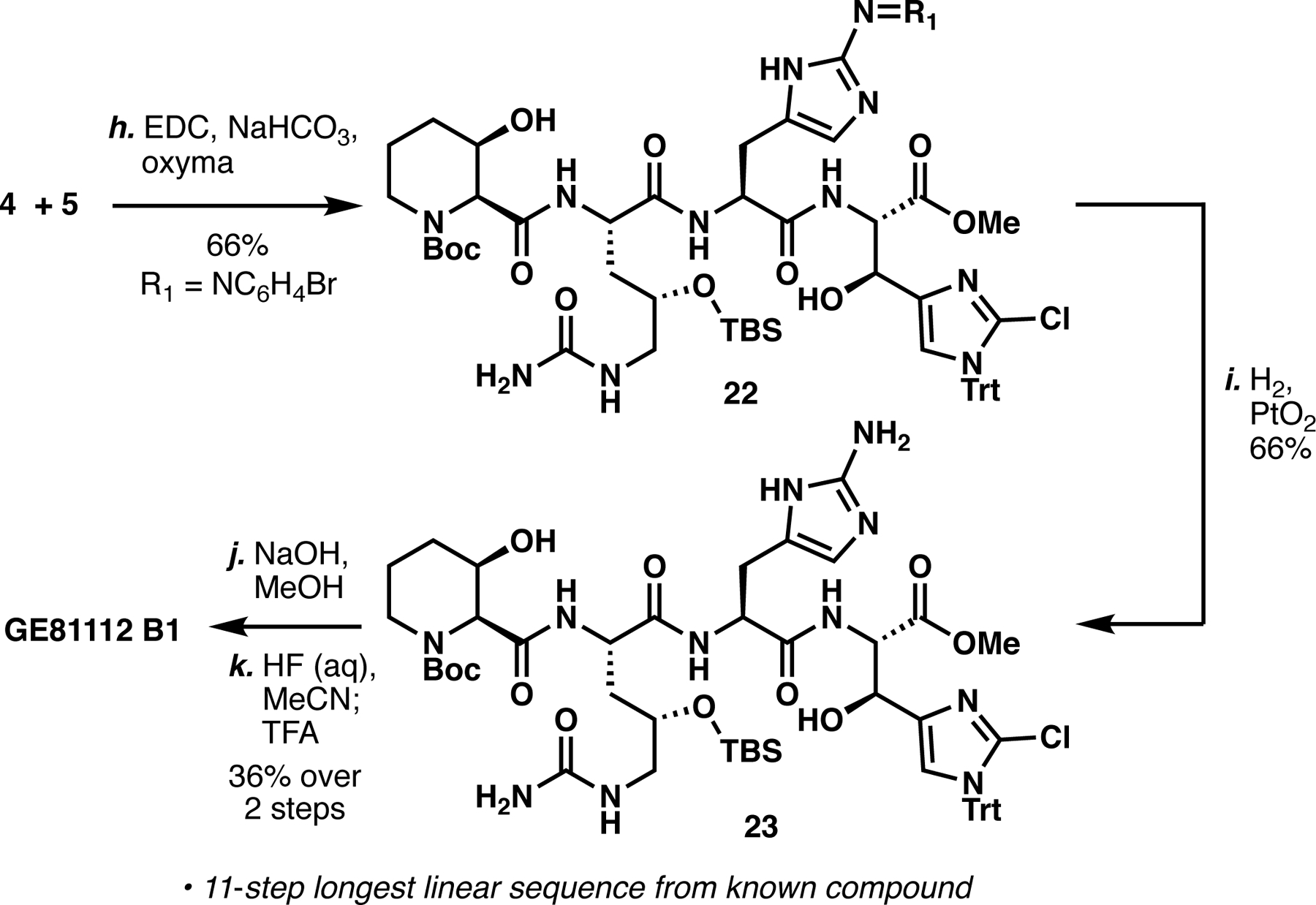

With conditions for late-stage azo removal in hand, we next targeted dipeptide 5 (Scheme 2C). Careful temperature control (e.g. slow warm from −40 °C to rt) proved necessary to avoid epimerization when coupling 8 and 9. Under these conditions, diasteriomerically pure product could be obtained in 79% over two steps.4 Similar to 10, Boc deprotection required exceptionally mild conditions to avoid Trt deprotection, therefore we tested silyltriflates buffered by 2,6-lutidine (Table SI5). While TBSOTf and TESOTf resulted in stable TBS carbamate and Trt deprotection respectively, TMSOTf cleanly afforded 5 in 77% isolated yield.10 With fragments 4 and 5 in hand, we proceeded to construct the core tetrapeptide of GE81112 B1 (Scheme 3). Slow addition of 4 to a solution of 5, EDC, Oxyma and NaHCO3 cleanly afforded 22 as a single diastereomer in 66% isolated yield.4 In line with our model hydrogenation, 22 was chemoselectively reduced to amine 23 in 66% yield under the action of H2 and PtO2. Subsequent methyl ester hydrolysis followed by global deprotection and HPLC purification yielded GE81112 B1 in 36% over two steps as the TFA salt.

Scheme 3.

Peptide coupling of 4 and 5 followed by deprotection sequence to complete the synthesis of GE81112 B1.

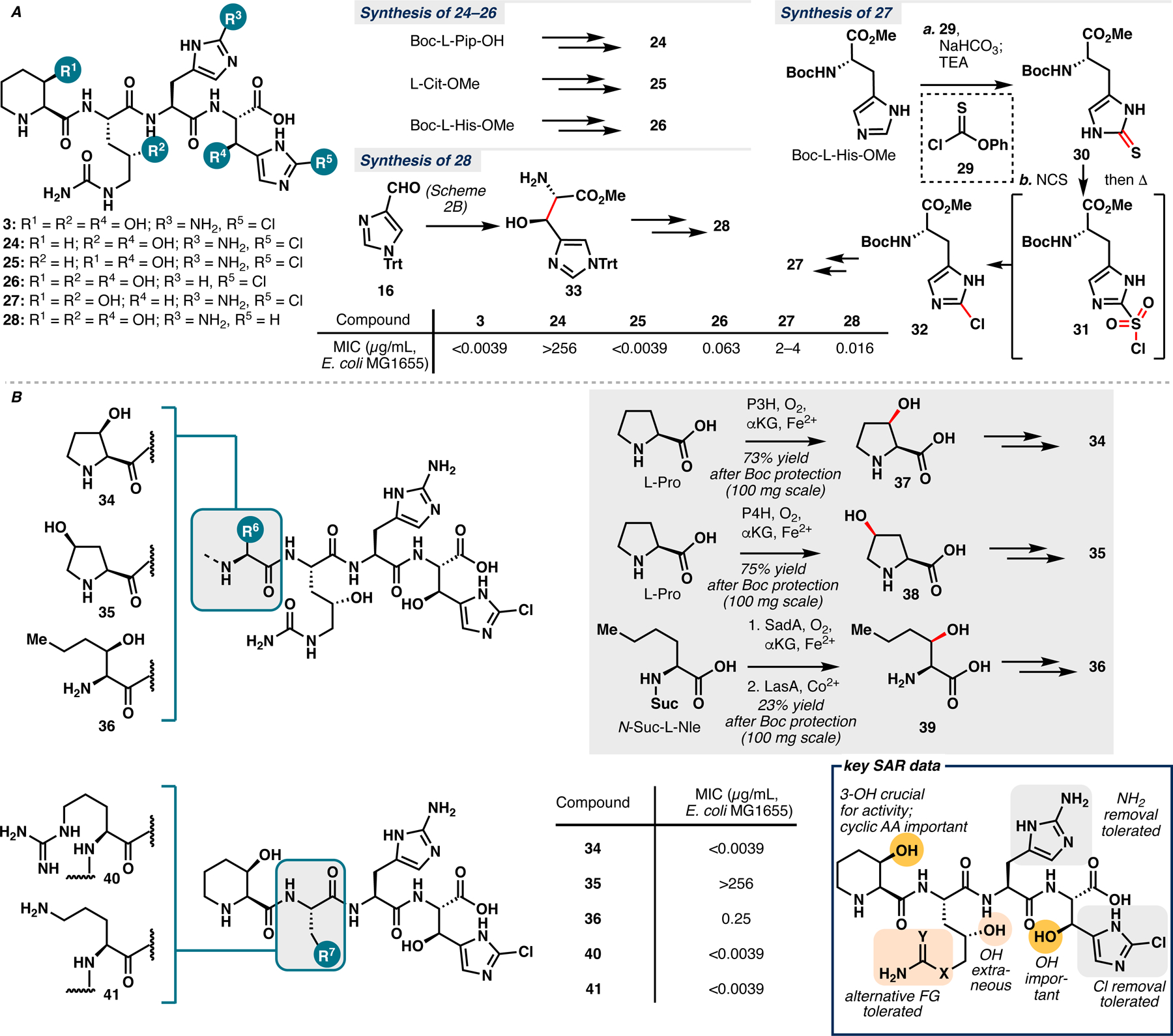

Having established a tractable route to GE81112 B1 (3), we set out to determine its key pharmacophores that significantly contribute to its antimicrobial activity. Prior effort by Fabbretti et al. has resulted in a solved crystal structure of 3:30S complex.2b However, we noted a lack of electron density around the ligand in this structure, which likely renders it unreliable for structure-based analog design. Conversely, SAR investigation between 3 and its antimicrobial activity would shed light into the contribution of each structural motif to the inhibitory activity of the tetrapeptide and aid future efforts in designing superior analog(s) or simplified analog(s) with comparable activity. First, we sought to assess the importance of the five peripheral modifications for inhibitory activity (Scheme 4A). To this end, we prepared five simplified analogs of 3 (24–28), each containing one less peripheral modification than the parent natural product. Synthesis of analogs 24, 25 and 26 proceeded in a routine fashion, requiring the use of readily available building blocks Boc-L-Pip-OH, L-Cit-OMe and Boc-L-His-OMe respectively in a route that is almost identical to Schemes 1–3.

Scheme 4.

A. Synthesis of simplified analogs 24–28 and their MIC measurements. B. Synthesis of analogs containing alternative hydroxylated amino acids at AA1 (34–36) and alternative amino acids at AA2 (40, 41) and their MIC measurements. MIC values are provided as a range obtained from three measurements.

Previously, we reported the synthesis of Cl-L-His-OMe 32 for functional characterization of GetI.6c While useful for analytical scale preparation of 32, our reported approach suffers from low yield and limited scalability. In turn, preparation of analog 27 necessitated the development of a novel strategy that remedies these synthetic shortcomings towards 2-chloro-L-histidine. Direct chlorination of Boc-L-His-OMe gave only C4 chlorination using SEAr conditions (NCS or PIDA/NaCl) or the ketone following lithiation (Figure SI4).15 An effective ANRORC reaction with phenyl chloroformate afforded oxo-Boc-L-His-OMe (SI29) in 85% yield, although only minor amounts of 32 were observed while testing various chlorination conditions from this intermediate.16a Success was finally achieved by developing an analogous ANRORC reaction utilizing phenyl thionochloroformate (29) to produce thio-Boc-L-His-OMe 30 in 90% yield.16b Chemoselective oxidation of 30 with NCS afforded the intermediate sulfonyl chloride (31), which was then converted to 32 following desulfination under gentle heating.17a This novel reaction sequence proceeds on >500 mg scale without any observable loss in isolated yield, solving the key limitations observed in our previous route. The unique desulfinative chlorination from 31 to 32 may proceed via the intermediacy of a chlorine radical that participates in ipso substitution of the sulfonyl chloride, regenerating chlorine radical following sulfur dioxide extrusion.17b Although the exact precursor to a chlorine radical is puzzling, this mechanism seems operative, given many analogous literature reactions that proceed under standard radical chlorination conditions.17b,c Another possibility involves concerted homolysis of the C–S and S–Cl bonds in 31, followed by recombination of the resulting carbon and chlorine radicals to 32.17a,d However, this mechanism seems less likely given the high bond dissociation energy (BDE) of C–S and S–Cl bonds (~67 kcal/mol).17d Further studies are underway to elucidate the mechanism of this transformation.

Further difficulty in the synthesis of 27 was experienced when the trityl-protected derivative of 32 proved to be more labile than 9, posing significant challenge in selective Boc deprotection after coupling with 8. As a workaround, linear assembly to a tripeptide intermediate consisting of 6, 7 and 8 was first prepared and submitted to a final peptide coupling with SI32, which provided analog 27 after deprotection. Our synthesis of 27 delineates an alternative assembly strategy to the GE81112 core that is additionally more well-suited to diversity-oriented synthesis in the production of large numbers of analogs. Finally, the use of a Franck aldol on aldehyde 16 and selective azide reduction provided protected β-hydroxy-L-histidine 33, albeit in diminished yield and diastereoselectivity. Nevertheless, 33 could be submitted to the same synthetic sequence described in Schemes 2 and 3 to afford analog 28.

Analogs 24–28 were next subjected to antibacterial assays, consisting of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) measurements against E. coli strain MG1655 in minimal media with 3 and gentamycin as a control. The MIC obtained for 3 was in close agreement with previous data in the literature.1,3,4 Analog 24 was found to be completely inactive. In conjunction with previous finding from Sanofi, this result suggests that the syn- β-hydroxy amino acid unit in AA1 is highly crucial for inhibitory activity.4 Analog 25, containing unmodified L-Cit at AA2 was found to maintain the antibacterial activity of the parent natural product. This finding points to the extraneous nature of the γ-OH unit in AA2 for activity and also the possibility of further developing simplified analog(s) of 3 with equipotent antibacterial activity. Removal of the C2-NH2 moiety in AA3 or C2-Cl in AA4 only reduced the activity of the resulting compounds by 5–15 fold, while removal of the β-OH in AA4 led to a more than 500-fold reduction in activity. These data show that the β-OH motif is the most crucial peripheral modification within the AA3-AA4 dipeptide for antibacterial activity.

In light of the above data, we next sought to further investigate the structural requirements for antibacterial activity at the AA1 and AA2 positions (Scheme 4B). The importance of the syn- β-hydroxy amino acid unit in AA1 begged the question whether this property is highly specific to 3-hydroxy-L-pipecolic acid or whether substitution with other hydroxylated amino acids, either cyclic or acyclic, is tolerated at this position. To this end, we synthesized three analogs containing cis-3-hydroxy-L-proline, cis-4-hydroxy-L-proline and cis-3-hydroxy-L-norleucine at AA1 (34, 35 and 36 respectively). The corresponding AA1 building blocks for these analogs were all prepared through the use of enzymatic hydroxylations with the appropriate Fe/αKGs. Thus, L-Pro was submitted to hydroxylation with two different Fe/αKG proline hydroxylases, P3H18a,b,c,d and P4H19, to afford 37 and 38. To synthesize 39, we leveraged a previous report describing a two-enzyme system20 that converts N-succinylated aliphatic amino acids to their β-hydroxylated free amino acid counterparts via hydroxylation with the Fe/αKG SadA, followed by N-desuccinylation with LasA. In our hands, modifications to the originally reported procedure were found necessary (see Supporting Information Table SI7 for details). Firstly, the reported one-pot protocol proved problematic in our hands. We elected instead for a two-step procedure consisting of β-hydroxylation of N-Suc-L-Nle with SadA, followed by C18 purification, and then subjection of the hydroxylated product to desuccinylation with LasA to afford 39. Additionally, adjustments to several key reaction parameters, such as relative enzyme concentrations, reaction time and temperature, for both SadA and LasA had to be made as well for robust production of 39. Conversion of 37, 38 and 39 to 34, 35 and 36 proceeded in a routine fashion following previously established route (Schemes 1–3). MIC measurements revealed that 34 is equipotent to 3 while 35 is completely inactive, suggesting strict requirement for syn-β-hydroxy amino acid at the AA1 position, which cannot be rescued even by syn-γ-hydroxy amino acid. On the other hand, analog 36 displayed almost 100-fold loss in activity. This observation shows the importance of cyclic amino acid motif at the same position, likely due to its superior conformational rigidity relative to its acyclic counterpart. It is worth emphasizing that the generation of these key SAR data is greatly facilitated by the use of biocatalytic hydroxylation, as some of the building blocks needed are not readily accessible by any other means. For example, 37 is only available commercially at $400/g and asymmetric aldol to prepare 39 using Franck’s method12 would be problematic as the method is known to be incompatible with aliphatic aldehydes.

In similar fashion, two other analogs, 40 and 41, were synthesized to probe the structural requirements at the AA2 position, specifically with regards to the functional group at its δ position. In light of prior SAR data with analog 25, no γ-OH group was introduced at the AA2 position of these analogs and their synthesis was accomplished in a straightforward fashion from suitably-protected L-Arg and L-Orn. We initially presumed that a ureido or a carbamate motif on AA2 is needed to elicit favorable polar or hydrogen bonding interactions in the binding based on the antibacterial profile of all three natural congeners of GE81112. Interestingly, analogs 40 and 41 were found to be just as potent as 3 in MIC tests with E. coli MG1655. These findings suggest that several alternative functional groups can be introduced at the δ position of AA2 without any deleterious effects on antibacterial activity against E. coli.

Conclusion

This work describes the development of a chemoenzymatic strategy to arrive at the first synthesis of GE81112 B1, and the application of this strategy for the synthesis of ten analogs. By combining biocatalytic hydroxylation and traditional chemical methods, we developed a strategy that requires only 2–5 steps (3 steps average) to synthesize each AA fragment. Additionally, our hybrid approach allows each key fragment to be prepared with high levels of stereocontrol. Thus, our strategy not only constitutes a distinct departure from contemporary approaches to morphed peptide synthesis, but also provides a robust solution to some of the shortcomings encountered in previous synthetic studies on GE81112 A.4

Similar to our previous work,8,9,21 this report highlights the strategic benefits of using enzymatic C–H oxidation to streamline access to complex, bioactive natural products. Our efficient strategy to access GE81112 B1 also enabled the preparation of ten analogs, which in turn allowed us to elucidate the key pharmacophores of GE81112 B1 and obtain the most exhaustive SAR insights into its inhibitory activity to date. Some of the key SAR insights obtained include the paramount importance of the syn-β-hydroxy amino acid at the AA1 position and the β-OH on AA4 for antibacterial activity and the surprising tolerance of the scaffold towards substitutions at the AA2 position. Though five of the analogs described in this work are just as active as the parent natural product in tests against E. coli, it is possible that some may display different antibacterial profiles against other pathogens. Additionally, some of these analogs may exhibit alternative uptake mechanism and the laxed SAR profile at the AA2 position may provide an opportunity to develop pro-drug or delivery strategies that bypass the need for Opp-mediated transport. Continued investigation on these issues is ongoing in our laboratory.

From a strategic perspective, this work provides a robust validation for the use of other Fe/αKG amino acid hydroxylases in generating unnatural analogs of GE81112 B1 through a chemoenzymatic approach, which should compare favorably to efforts relying solely on synthetic chemistry or biosynthetic engineering. As illustrated in our synthesis of 34–36, these hydroxylations can be applied in a modular fashion to generate analogs that are not readily accessible otherwise, thereby enabling efficient exploration of novel chemical space. The strategy outlined here is expected to be broadly applicable to the medicinal chemistry exploration of other highly-oxidized peptides wherein a pool of Fe/αKG hydroxylases could be employed to rapidly perform SAR studies on a lead molecule to elucidate key pharmacophores and identify superior analogs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM128895 (H.R.) and S10 OD021550 (for 600 MHz NMR instrumentation). We thank Prof. Ian Seiple for useful discussions on asymmetric aldol reactions. We thank Drs. Andrew Steele and Christiana Teijaro for providing assistance with MIC measurements. We acknowledge the Roush, Bannister, Kodadek and Shen labs for generous access to their reagents and instrumentation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS publications website.

Experimental details, analytical data, 1H and 13C NMR data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandi L; Lazzarini A; Cavaletti L; Abbondi M; Corti E; Ciciliato I; Gastaldo L; Marazzi A; Feroggio M; Fabbretti A; Maio L; Colombo L; Donadio S; Marinelli F; Losi D; Gualerzi CO; Selva E Novel Tetrapeptide Inhibitors of Bacterial Protein Synthesis Produced by a Streptomyces sp. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 3692–3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Brandi L; Abbondi M; Fabbretti A; Donadio S; Losi D; Gualerzi CO Specific, efficient, and selective inhibition of prokaryotic translation initiation by a novel peptide antibiotic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2006, 103, 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fabbretti A; Andreas S; Brandi L; Kaminishi T; Giuliodori AM; Garofalo R; Ochoa-Lizarralde B; Takemoto C; Yokoyama S; Connell SR; Gualerzi CO; Fucini P Inhibition of translation initiation complex formation by GE81112 unravels a 16S rRNA structural switch involved in P-site decoding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2016, 113, E2286–E2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) López-Alonso JP; Fabbretti A; Kaminishi T; Iturrioz I; Brandi L; Gil-Carton D; Gualerzi CO; Fucini P; Connell SR Structure of a 30S pre-initiation complex stalled by GE81112 reveals structural parallels in bacterial and eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation pathways. Nucleic Acids Research 2017, 45, 2179–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maio A; Brandi L; Donadio S; Gualerzi CO The Oligopeptide Permease Opp Mediates Illicit Transport of the Bacterial P-site Decoding Inhibitor GE81112. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jürjens G; Schuler SMM; Kurz M; Petit S; Couturier C; Jeannot F; Nguyen F; Wende RC; Hammann PE; Wilson DN; Bacqué E; Pöverlein C; Bauer A Total Synthesis and Structural Revision of the Antibiotic Tetrapeptide GE81112. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 12157–12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Turner NJ; O’Reilly E Biocatalytic retrosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol 2013, 9, 285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) de Souza ROMA; Miranda LSM; Bornscheuer UT A Retrosynthesis Approach for Biocatalysis in Organic Synthesis. Chem. -Eur. J 2017, 23, 12040–12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Binz TM; Maffioli SI; Sosio M; Donadio S; Müller R Insights into an Unusual Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetase Biosynthesis Identification and Characterization of the GE81112 Biosynthetic Gene Cluster. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285, 32710–32719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mattay J; Hüttel W Pipcolic Acid Hydroxylases: A Monophyletic Clade among cis-Selective Bacterial Proline Hydroxylases that Discriminates L-Proline. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1523–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zwick CR III; Sosa MB; Renata H Bioinformatics-Guided Discovery of Citrulline 4-Hydroxyalse from GE81112 Biosynthesis and Rational Engineering of Its Substrate Specificity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 18854–18858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaganathen A; Ehret-Sabatier L; Bouchet M-J; Goeldner MP Synthesis and Properties of a 2-Diazohistidine Derivative: A New Photoactivatable Aromatic Amino-Acid Analog. Helvetica Chimica Acta 1990, 73, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X; Renata H Efficient chemoenzymatic synthesis of (2S,3R)-3-hydroxy-3-methylproline, a key fragment in polyoxypeptin A and FR225659. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 3253–3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Zhang X; King-Smith E; Renata H Total Synthesis of Tambromycin by Combining Chemocatalytic and Biocatalytic C–H Functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 5037–5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Thomas JG; Ayling A; Baneyx F Molecular chaperones, folding catalysts, and the recovery of active recombinant proteins from E. coli. To fold or to refold. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol 1997, 66, 197–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Sakaitani M; Ohfune Y Selective Transformation of N-t-Butoxycarbonyl Group into N-Alkoxy-Carbonyl Group via N-Carboxylate Ion Equivalent. Tet. Lett 1985, 26, 5543–5546. [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang Y-H; Liu R; Liu B Total synthesis of nannocystin Ax. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 5549–5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li P; Evans CD; Wu Y; Cao B; Hamel E; Joullié MM Evolution of the Total Synthesis of Ustiloxin Natural Products and Their Analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 2351–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d). Nuhant P; Roush WR Enantio- and Diastereoselective Synthesis of N-Acetyl Dihydrotetrafibricin Methyl Ester. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5340–5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seiple IB; Mercer JAM; Sussman RJ; Zhang Z; Myers AG Stereocontrolled synthesis of syn-α-Hydroxy-β-amino acids by direct aldolization of pseudoephenamine glycinamide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 4642–4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel J; Clavé G; Renard P-Y; Franck X Straightforward Access to Protected syn α-Amino-β-hydroxy Acid Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008, 47, 4224–4227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boger DL; Colletti SL; Honda T; Menezes RF Total Synthesis of Bleomycin A2 and Related Agents. 1. Synthesis and DNA Binding Properties of the Extended C- Terminus: Tripeptide S, Tetrapeptide S, Pentapeptide S, and Related Agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 5607–5618. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubriks D; Sokolovs I; Suna E Indirect C–H Azidation of Heterocycles via Copper-Catalyzed Regioselective Fragmentation of Unsymmetrical l3-Iodanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 15436–15442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Jain R; Avramovitch B; Cohen LA Synthesis of Ring-Halogenated Histidines and Histamines. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 3235–3242. [Google Scholar]; b) Himabundu V; Parvathaneni SP; Rao VJ PhI(OAc)2/NaX-Mediated Halogenation Prodiving Access to Valuable Synthons 3-Haloindole Derivatives. New J. Chem 2018, 42, 18889–18893. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Adam W; Zhao C-G; Jakka K Dioxirane Oxidations of Compounds Other Than Alkenes. Org. React 2007, 1–346. [Google Scholar]; b) Xu J; Yadan JC Synthesis of L-(+)-Ergothioneine. J. Org. Chem 1995, 60, 6296–6301. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Ford ME; Dixon DD Novel Chlorination of the 1,3,4-Thiadiazole Ring. J. Heterocycl. Chem 1980, 17, 1311–1312. [Google Scholar]; b) Miller B; Walling C The Displacement of Aromatic Substituents by Halogen Atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1957, 79, 4187–4191. [Google Scholar]; c) Traynham JG Ipso Substitution in Free-Radical Aromatic Substitution Reactions. Chem. Rev 1979, 79, 323–330. [Google Scholar]; d) Navrotskii AV; Stepanov GV; Safronov SA; Gaidadin AN; Seleznev AA; Navrostskii VA Novakov IA Homolytic Decomposition of Sulfonyl Chlorides. Doklady Chemistry 2018, 480, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Mori H; Shibasaki T; Yano K; Ozaki A Purification and Cloning of a Proline 3-Hydroxylase, a Novel Enzyme Which Hydroxylases Free L-Proline to cis-3-Hydroxy-L-Proline. J. Bacteriol 1997, 179, 5677–5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shibasaki T; Sakurai W; Hasegawa A; Uosaki Y; Mori H; Yoshida M; Ozaki A Substrate Selectivities of Proline Hydroxylases. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 5227–5230. [Google Scholar]; c) Shibasaki T; Mori H; Ozaki A Cloning of an Isozyme of Proline-3-Hydroxylase and Its Purification from Recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett 2000, 22, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar]; d) Johnston RM; Chu LN; Liu M; Goldberg SL; Goswami A; Patel RN Hydroxylation of L-Proline to cis-3-Hydroxy-L-Proline by Recombinant Escherichia coli Expressing a Synthetic L-Proline-3-Hydroxylase Gene. Enzyme Microb. Technol 2009, 45, 484–490. [Google Scholar]; e) Du Y; Wang Y; Huang T; Tao M; Deng Z; Lin S Identification and Characterization of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster of Polyoxypeptin A, a Potent Apoptosis Inducer. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara K; Kino K Characterization of Novel 2-Oxoglutarate Dependent Dioxygenases Converting L-Proline to cis-4-Hydroxy-L-Proline. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2009, 379, 882–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibi M; Kasahara T; Kawashima T; Yajima H; Kozono S; Smirnov SV; Kodera T; Sugiyama M; Shimizu S; Yokozeki K; Ogawa J Multi-Enzymatic Synthesis of Optically Pure β-Hydroxy α-Amino Acids. Adv. Synth. Catal 2015, 357, 767–774. [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Zwick CR III; Renata H Remote C–H Hydroxylation by an α -Ketoglutarate-Dependent Dioxygenase Enables Efficient Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Manzacidin C and Proline Analogs. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 1165–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zwick CR III; Renata H Evolution of Biocatalytic and Chemocatalytic C–H Functionalization Strategy in the Synthesis of Manzacidin C. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 7407–7415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zwick CR III; Renata H A One–Pot Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of (2S,4R)-4-Methylproline Enables the First Total Synthesis of Antiviral Lipopeptide Cavinafungin B. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 6469–6473. [Google Scholar]; d) Amatuni A; Renata H Identification of a lysine 4-hydroxylase from the glidobactin biosynthesis and evaluation of its biocatalytic potential. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 1736–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.