Highlights

-

•

We used data from a large-scale, pandemic-focused, UK-wide cohort study.

-

•

Lower cognition was robustly associated with COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy.

-

•

Of concern, elsewhere, lower cognition is also related to higher COVID-19 rates.

Keywords: Cognitive function, Cognitive ability, IQ, Mental ability, COVID-19, Vaccine hesitancy, Cohort

Abstract

Background

Whereas several predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy have been reported, the role of cognitive function is largely unknown. Accordingly, our objective was to evaluate the association between scores from an array of cognitive function tests and self-reported vaccine hesitancy after the announcement of the successful testing of the first COVID-19 vaccine (Oxford University/AstraZeneca).

Methods

We used individual-level data from a pandemic-focused study ('COVID Survey'), a prospective cohort study nested within United Kingdom Understanding Society ('Main Survey'). In the week immediately following the announcement of successful testing of the first efficacious inoculation (November/December 2020), data on vaccine intentionality were collected in 11,740 individuals (6702 women) aged 16–95 years. Pre-pandemic scores on general cognitive function, ascertained from a battery of six tests, were captured in 2011/12 wave of the Main Survey. Study members self-reported their intention to take up a vaccination in the COVID-19 Survey.

Results

Of the study sample, 17.2% (N = 1842) indicated they were hesitant about having the vaccine. After adjustment for age, sex, and ethnicity, study members with a lower baseline cognition score were markedly more likely to be vaccine hesitant (odds ratio per standard deviation lower score in cognition; 95% confidence interval: 1.76; 1.62, 1.90). Adjustment for mental and physical health plus household shielding status had no impact on these results, whereas controlling for educational attainment led to partial attenuation but the probability of hesitancy was still elevated (1.52; 1.37, 1.67). There was a linear association for vaccine hesitancy across the full range of cognition scores (p for trend: p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Erroneous social media reports might have complicated personal decision-making, leading to people with lower cognitive ability being vaccine-hesitant. With individuals with lower cognition also experiencing higher rates of COVID-19 in studies conducted prior to vaccine distribution, these new findings are suggestive of a potential additional disease burden.

1. Introduction

Cognitive function – also known as mental ability or intelligence – refers to psychological functions that involve the storage, selection, manipulation, and organisation of information, and the planning of actions (Deary, 2012, Deary and Batty, 2007). Assessed using standard tests, there is marked inter-person variation in how rapidly and precisely people carry out these mental tasks (Deary, 2012, Deary and Batty, 2007). Health protection and health care can also be regarded as a complex set of assignments that require assimilation of knowledge, decision-making, and planning. It has been posited that people with higher cognitive function manage preventative behaviours and treatment more effectively (Gottfredson, 2004), and there is growing evidence that this is the case.

In well-characterised cohort studies, relative to their lower-performing counterparts, people with higher ability are more likely to have a healthy diet (Batty et al., 2007b), choose dietary supplements (Whalley et al., 2003), and be physically active (Batty et al., 2007b). Those who score better on cognitive tests also have a lower probability of smoking cigarettes (Batty et al., 2007a, Batty et al., 2007c), drinking harmful levels of alcohol (Batty et al., 2006), and having associated problems (Batty et al., 2008). Cessation rates are also elevated in smokers with higher mental ability Taylor et al., 2005). Further, in individuals with a greater risk of a first cardiovascular disease event (Deary et al., 2009), in those with a higher probability of re-infarction,(Wallert et al., 2017) and in patients with respiratory disease (O'Conor et al., 2019), improved compliance with known efficacious drug therapies is apparent with higher ability scores. Similarly, in people with an elevated risk of colorectal cancer, rates of participation in a free screening programme were elevated in persons with better performance on tests of cognition (Gale et al., 2015).

These observations provide circumstantial evidence for a link between cognitive ability and another health-protecting behaviour, vaccine uptake. Vaccination is central to controlling the present pandemic, with success reliant on a sufficiently high uptake to achieve herd immunity (Omer et al., 2020). In the only empirical investigation of which we are aware, a very brief measure of analytical reasoning was administered to people in two small cross-sectional studies from the UK (N = 2025) and Ireland (N = 1041) (Murphy et al., 2021). Relative to the group who indicated they would be likely to accept a COVID-19 inoculation if one became available, somewhat lower cognition scores were apparent in study members indicating vaccine reticence (Murphy et al., 2021). These data were collected in March/April 2020 when no efficacious vaccine had been tested. Around 8 months later, following periodic statements to the media of its on-going development, successful testing of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine, the first known efficacious inoculation against COVID-19, was announced (Gallacher, 2020). Time-series analyses across multiple countries potentially implicates this declaration and those for other vaccines in having a positive impact upon intentionality (YouGov, 2021). Accordingly, for the first time to our knowledge, we investigated the link between cognitive function and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a large UK general population-based sample in which data collection took place following the announcement of an efficacious vaccine.

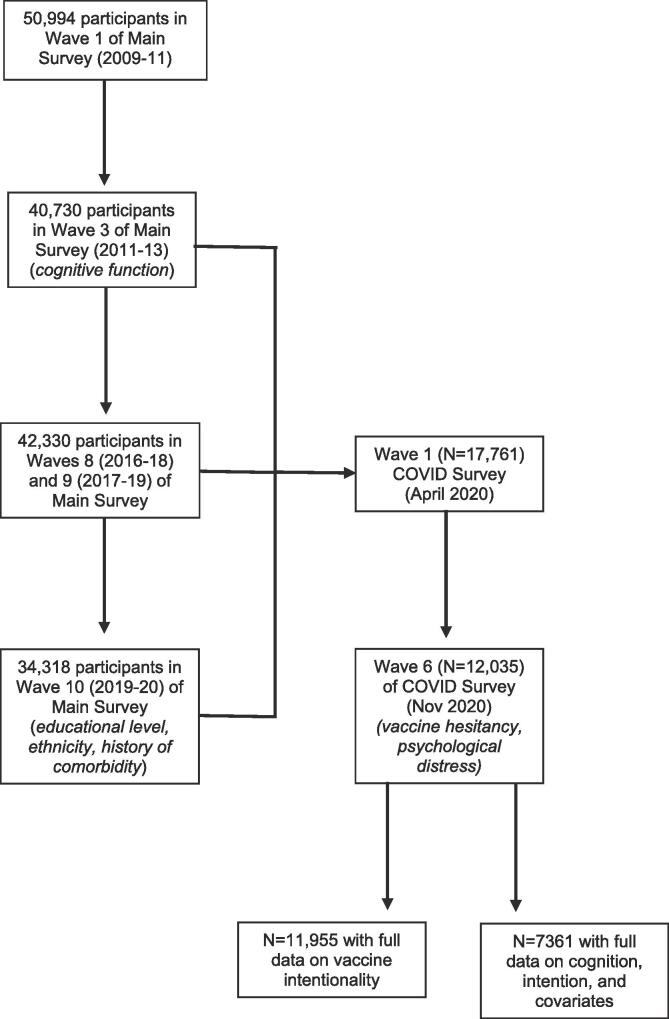

2. Methods

Understanding Society, also known as the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study, is a nationally-representative, on-going, open, cohort study (hereinafter, the ‘Main Survey’) (University of Essex, 2020). Based on a clustered-stratified probability sample of households, participants have been interviewed annually since 2009. Households who had participated in at least one of the two most recent waves of data collection (wave 8, 2016–18; wave 9, 2017–19) comprised the target sample for a pandemic-focused study initiated in April 2020 (hereinafter, the ‘COVID Survey’) (University of Essex, 2021). The derivation of the present analytical sample from the Main and COVID surveys, including the wave in which relevant data were collected, is depicted in Fig. 1. The University of Essex Ethics Committee gave approval for data collection in the COVID-orientated surveys (ETH1920-1271); no further ethical permissions were required for the present analyses of anonymised data.

Fig. 1.

Flow of cohort members into the analytical sample: Main Survey and COVID Survey in Understanding Society

The COVID Surveys took place monthly/bimonthly between April (wave 1) and, at the time of analyses, November 2020 (wave 6), with questions on vaccine intention first administered in the November wave when study members were aged 16–95 years (mean 53). Data collection in wave 6 (starting 24th November) commenced the day immediately following the announcement of the efficacy of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine (Gallacher, 2020) and continued for one week, comprising a total of 12,035 individuals of 19,294 invitations issued (response proportion, 62%).

2.1. Assessment of cognitive function

In the third wave of data collection in the Main Survey (2011–2013), six cognitive function tests were administered following piloting (Gray et al., 2011, McFall, 2013). Representing a range of cognitive skills, these tests have been repeatedly deployed in large-scale, population-based studies (Borsch-Supan et al., 2013, Lachman et al., 2010, Richards et al., 2004, Sonnega et al., 2014, Steptoe et al., 2013). Verbal declarative memory was assessed using both immediate word recall and delayed word recall tasks. Respondents listened to a list of ten words delivered by a computer; they were then asked to immediately recall the words and, again, at a later stage in the interview without having heard the words again. The number of correct responses was recorded on each occasion. For semantic verbal fluency, respondents named as many animals as they could in one minute; the final score was based on the number of unique correct responses. Using components of screening instruments for cognitive impairment including the Mini Mental State Examination (Crum et al., 1993) and the Cambridge Cognitive Examination (Huppert et al., 1995), respondents were asked to subtract 7 from 100 and then subtract 7 from their answer on four more occasions. The number of correct responses of a maximum of five was recorded. Fluid reasoning was assessed using a number sequence in which the respondent populated the gap(s) in a logical series. Respondents were initially presented with simple examples to test their understanding; those who seemed confused or unable to understand test requirements after the relaying of two examples were excused from the test. Remaining study members were administered two sets of three number sequences, with the difficulty of the second set determined by their performance on the first. A score was derived which accounts for the difficulty of the items. Lastly, for numerical reasoning skills, individuals were given three numerical problems to solve and, depending on their responses, were then administered a further one (simpler) or two (more difficult) problems. The total number of correct responses was recorded.

2.2. Assessment of covariates

Covariates were self-reported and included age; sex (both wave 10 [2019–20], Main Survey); ethnicity (wave 10, Main Survey; denoted as white or non-white); highest education level (wave 10, Main Survey; categorised as degree & other higher degree, A’ level or equivalent [Advanced Placement in the US], GCSE or equivalent [Grade 10 in the USA], other qualification, and none); and National Health Service-recommended shielding status for any household member (waves 1–5 [April-September 2020], COVID Surveys; denoted by yes/no). A history of physical morbidities was also captured (wave 10, Main Survey) and based on any mention of a cardiometabolic condition (congestive heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina, heart attack or infarction, stroke, diabetes, and/or hypertension); respiratory disease (respiratory disease comprised bronchitis, emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and/or asthma); or cancer of any type. Current psychological distress (wave 6 [November 2020], COVID Survey) was ascertained using the administration of the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire. Validated against standardised psychiatric interviews (Hankins, 2008, Holi et al., 2003), this is a widely used measure of distress (anxiety and depression) in population-based studies. Consistent with published analyses (Russ et al., 2011, Russ et al., 2015, Russ et al., 2012), we used a score of ≥ 3 to denote psychological distress.

2.3. Assessment of vaccine intentionality

At wave 6 in the COVID Survey, study members were asked “Imagine that a vaccine against COVID-19 was available for anyone who wanted it. How likely or unlikely would you be to take the vaccine?”. Possible responses were “Very likely”, “Likely”, “Unlikely” and “Very unlikely”. The latter two categories were combined to denote vaccine hesitancy.

3. Statistical analyses

It is well-replicated that performance on tests of cognitive abilities are positively inter-related, whereby people who score highly on one test of cognition tend to score well on another (Deary, 2012). This has led to the use of the term ‘general cognitive ability’, usually known as ‘g’. Accordingly, using scores from the six tests of cognitive function we generated a single general cognitive function variable. Computed using principal components analysis, the first unrotated component of the six cognitive tests was used as a single measure of cognitive function (variance explained: 42%; loadings: immediate recall 0.74, delayed recall 0.72, verbal fluency 0.59, serial sevens 0.49, number series 0.64, numerical problem solving 0.66). To summarise the relation between cognition and vaccine hesitancy, we used logistic regression to compute odds ratios with accompanying 95% confidence intervals. In these analyses we calculated effect estimates for tertiles of cognitive function scores (highest was the referent group) and those for a unit (standard deviation) disadvantage in score. The most basic analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity. Retaining these covariates, we then explored the impact of separately controlling for existing somatic medical conditions, mental health, education, and shielding status.

4. Results

In a sample of 11,955 individuals who responded in full to the enquiry regarding COVID-19 vaccine intentionality, 17.2% (N = 1842) indicated that they were hesitant. In Table 1 we show unadjusted study member characteristics according to vaccine intention. Relative to the group who indicated a willingness to have the vaccine, those who were hesitant were more likely to be young, female, from an ethnic minority background, and be less well educated. The hesitant were also less likely to carry an array of existing somatic morbidities and be shielding or live with someone who was. The prevalence of psychological distress was somewhat higher in the vaccine hesitant.

Table 1.

Study member characteristics according to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Understanding Society

| Vaccine hesitant |

P value for difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Numbers of people (%) | 1842 (17.2) | 10,113 (82.8) | - |

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 45.0 (14.5) | 54.6(15.6) | <0.0001 |

| Female, N (%) | 1162 (63) | 5530 (55) | <0.0001 |

| Non-white ethnicity, N (%) | 406 (22.0) | 698 (7.0) | <0.0001 |

| Socioeconomic factors | |||

| No university education, N (%) | 939 (51.0) | 4298 (42.5) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cardiometabolic disease, N (%) | 268 (15.0) | 2513 (25.2) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory disease, N (%) | 219 (12.3) | 1372 (13.8) | 0.144 |

| Any cancer, N (%) | 45 (2.5) | 525 (5.3) | <0.0001 |

| High psychological distress, N (%) | 509 (27.6) | 2399 (23.7) | <0.0001 |

| Shielding in the household, N (%) | 196 (10.6) | 1187 (11.7) | <0.0001 |

| Cognitive function | |||

| g factor, mean (SD) | 96.6 (15.7) | 100.5 (14.8) | <0.0001 |

Numbers of study members corresponds to those with complete data

on vaccine intentionality

There were also differences in cognitive function between the vaccine groups, whereby the vaccine hesitant study members had lower general ability scores (difference in mean score 3.9; p-value for difference: <0.0001). We investigated these differentials in more detail in Table 2 where we present the results of regression analyses incorporating potential explanatory variables in an analytical sample of 7361 people with full data for all the variables depicted; that is, a non-missing dataset (Fig. 1). In age-, sex- and ethnicity-adjusted analyses, a one standard deviation lower score in general cognitive ability was associated with a 76% greater risk of being vaccine hesitant (odds ratio; 95% confidence interval: 1.76; 1.62, 1.90). While separate adjustments for somatic comorbidity, psychological distress, and shielding had no impact on this relationship, adjustment for education led to some attenuation (1.52; 1.37, 1.67) – the Kendall rank correlation between cognition and educational attainment was 0.27 (p < 0.0001). Simultaneous adjustment for all covariates had no greater attenuating effect than the adjustment for education alone.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for the relation of general cognitive function with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Understanding Society

| Number hesitant/Total at risk | Age, sex, & ethnicity | Age, sex, ethnicity, & somatic comorbidity | Age, sex, ethnicity, & psychological distress | Age, sex, ethnicity, & shielding | Age, sex, ethnicity, & education | All covariates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 3 (high) | 236/2284 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 352/2918 | 1.28 (1.07, 1.54) | 1.29 (1.08, 1.55) | 1.28 (1.07, 1.54) | 1.29 (1.08, 1.55) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.41) | 1.18 (0.99, 1.42) |

| Tertile 1 | 365/2159 | 1.99 (1.66, 2.40) | 2.01 (1.67, 2.43) | 1.99 (1.66, 2.40) | 2.01 (1.67, 2.42) | 1.64 (1.35, 1.99) | 1.67 (1.37, 2.03) |

| P for trend | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | p < 0.0001 | |

| Per SD decrease | 953/7361 | 1.76 (1.62, 1.90) | 1.77 (1.63, 1.91) | 1.76 (1.62, 1.90) | 1.78 (1.64, 1.91) | 1.52 (1.37, 1.67) | 1.54 (1.40, 1.69) |

Numbers of study members in this sample corresponds to those with complete data on all variables in the analyses. Thresholds for categories of cognitive function: tertile 1 (>=108.3); tertile 2 (108.2–93.3); and tertile 1 (>=93.2). A standard deviation (SD) in general cognitive function was 15 units.

To gain insights into whether the association with vaccine hesitancy was linear, the analyses were repeated according to tertiles of cognitive function. In age-, sex- and ethnicity- adjusted analyses, relative to people in the highest-scoring cognition tertile, those in the lowest were twice as likely to be vaccine hesitant (1.99; 1.66, 2.40). People in the intermediate ability tertile had intermediate risk of hesitancy (1.28; 1.07, 1.54) such that an incremental effect was apparent across the cognition categories (p-value for trend: <0.0001). To explore the impact on loss to follow-up, we derived inverse probability weights. Repeating our main analyses, our results were essentially unchanged (Table 1a, appendix).

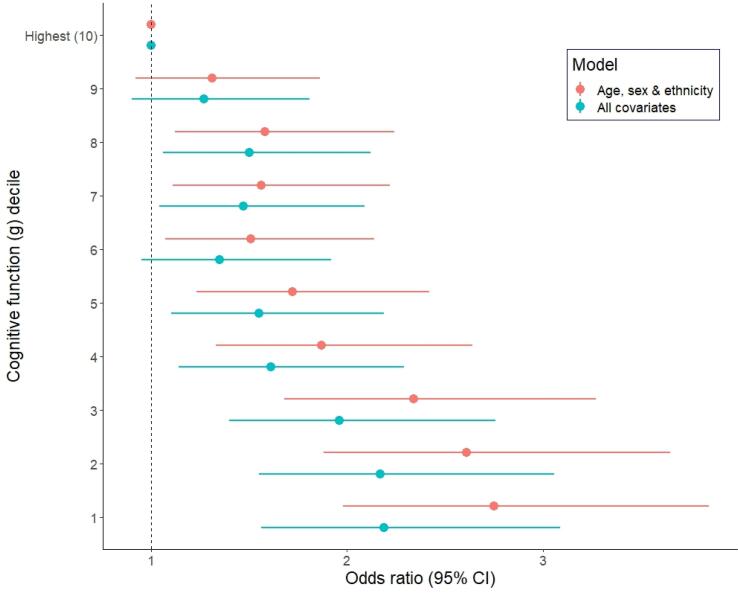

Lastly, in order to explore inflections in the cognition–hesitancy association, we utilised deciles of cognition in analyses. Again, there was evidence of a clear trend, although this was not perfectly stepwise across all categories (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for the relation of general cognitive function with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Understanding Society

5. Discussion

5.1. Principal findings

Our main finding was that, in data collected immediately following the announcement in the UK of an efficacious vaccine, and net of several covariates, people with lower scores on tests of cognitive function were less minded to take up an offer of vaccination for COVID-19 if it was made. These effects were apparent across the full range of cognition scores. That we were able to replicate known predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy – being female (Detoc et al., 2020, Freeman et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020), younger (Detoc et al., 2020, Freeman et al., 2020), non-white ethnicity,(Freeman et al., 2020, Robertson et al., 2021, Williams et al., 2021), and having a lower prevalence of physical morbidity(Ruiz and Bell, 2021) – gives us some confidence in our novel results for cognitive function.

5.2. Comparison with existing studies

To the best of our knowledge, as described, there has been one prior examination of the relationship between cognition and vaccine hestinacy (Murphy et al., 2021). Comprising two small cross-sectional studies where data collection took place before the announcement of vaccine test results, people who performed better on a short test of cognitive function were more likely to be vaccine-accepting (Murphy et al., 2021). We found similar results in using more detailed measures of cognitive function in a large sample which allowed us to explore the shape of the relationship across the full range of abilities. A closely related literature is that for education with which cognition is positively correlated (Neisser et al., 1996). This supports the present results whereby people with higher educational achievement were less likely to be vaccine-hesitant (Kuter et al., 2021, Nguyen et al., 2021).

5.3. Potential public health implications

We have recently shown that, in data collected prior to vaccine distribution, of a range of baseline psychosocial factors which included socioeconomic status, education, personality type, and mental health, cognitive function was the most strongly and robustly associated with subsequent incidence of severe COVID-19, such that a doubling of the risk of hospitalisation was apparent in the lowest scoring group (Batty et al., 2020a). This supports other data that individuals with higher cognitive function experience a lower risk of death from other respiratory diseases, including influenza and pneumonia (Gale et al., 2019). The notion that people with lower cognitive ability appear to have greater rates of severe COVID-19 (Batty et al., 2021a, Batty et al., 2020a) and, based on the present results are also less likely to take up the offer of vaccination, may further increase the disease burden in this group, as may also be the case for people from ethnic minority groups (Lassale et al., 2020, Robertson et al., 2021) and the socioeconomically disadvantaged (Batty et al., 2020a, Murphy et al., 2021).

5.4. Plausible explanations

Various explanations may be germane to the cognition–vaccine intention link, including the observation that people with higher cognitive ability are better equipped to obtain, process, and respond to disease prevention advice (von Wagner et al., 2009). There has been a deluge of health advice in the current pandemic during an era when news outlets and social media platforms have never been more ubiquitous and influential. Preventative information has ranged from the simple and practical to the complex, contradictory, false, and fraudulent. In order to diminish their risk of the infection, people have to acquire, synthesise, weigh-up, and deploy this information but the ability to do so seems to vary by levels of health literacy (Wolf et al., 2020) just as it may for its close correlate, cognitive function.

5.5. Study strengths and weaknesses

While the present study has its strengths, including its size, national representativeness, and timing, there are also some weaknesses. First, we used vaccine intentionality as an indicator vaccine uptake but the correlation is imperfect. In a small scale longitudinal study conducted during the period of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong, <10% of people who expressed a commitment to being inoculated reported that they had received a vaccination two months later (Liao et al., 2011). Elsewhere, in a US adult population at high risk of seasonal influenza, around half of those intending to be vaccinated had received the inoculation within the following 5 months (Harris et al., 2009). Second, there was inevitably some loss to follow-up (Fig. 1). While this attrition may have impacted upon the estimation of the prevalence vaccine hesitancy which is likely to be lower in our select sample relative to the general population (Fry et al., 2017), it is unlikely to have influenced our estimation of its relationship with cognitive function. Thus, in other contexts, we have shown that highly select cohorts reveal very similar risk factor–disease associations to those seen in studies with conventionally high response (Batty et al., 2020b). Also, as we have shown in sensitivity analyses, weighting had very little impact on the relation between cognitive function and vaccine hesitancy. Third, the 10 years period between cognitive testing and ascertainment of vaccine hesitancy raises concerns regarding the impact of changes in cognition function. While there was no retesting of cognition in the present study, findings from other studies suggest that cognitive function, even in older adults, is stable over a 10 year period, and, related, little mean decline will take place (Ritchie et al., 2019). Even less decline will have occurred in the present sample given that the age continuum covers all adulthood. There would also be modest inter-individual differences, such that people would largely retain their ranking from baseline. For context, all population characteristics are subject to some variation over time and cognition is no exception. As we have shown (Batty et al., 2021), in resurveys of samples of up to 31,000 individuals in UK Biobank, cognitive function scores (r = 0.63, p < 0.001, N = 9689) have comparable test–retest correlation coefficients compared with cigarette smoking (0.60, p < 0.001, N = 31,037), blood pressure (0.65, p < 0.001, N = 19,772), and diabetes (r = 0.63, P < 0.001, N = 31,037). As has been demonstrated (Clarke et al., 1999), this order of correlation may result in regression dilution that is likely to lead to underestimation of risk factor associations.

In conclusion, people with lower scores on standard tests of cognitive function reported being less willing to take up the future offer of vaccination for COVID-19. It is possible that erroneous social media news reports have complicated decision-making. Special efforts should be made to communicate clear information about vaccine efficacy and safety so that everyone—including those who report being less likely to choose vaccination—can make well-informed choices.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Batty, G.D., Deary, I., Gale, C., 2021a. Pre-pandemic cognitive function and COVID-19 mortality: prospective cohort study. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Gale C.R. Pre-pandemic cognitive function and COVID-19 mortality: prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10654-021-00743-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Luciano M., Altschul D.M., Kivimaki M., Gale C.R. Psychosocial factors and hospitalisations for COVID-19: Prospective cohort study based on a community sample. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89:569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., MacIntyre S. Childhood IQ and life course socioeconomic position in relation to alcohol induced hangovers in adulthood: the Aberdeen children of the 1950s study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:872–874. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., MacIntyre S. Childhood IQ in relation to risk factors for premature mortality in middle-aged persons: the Aberdeen Children of the 1950s study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61:241–247. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.048215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Schoon I., Emslie C., Hunt K., Gale C.R. Childhood mental ability and adult alcohol intake and alcohol problems: the 1970 British cohort study. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98:2237–2243. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.109488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Schoon I., Gale C.R. Childhood mental ability in relation to food intake and physical activity in adulthood: the 1970 British Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e38–e45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Schoon I., Gale C.R. Mental ability across childhood in relation to risk factors for premature mortality in adult life: the 1970 British Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61:997–1003. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Gale C.R., Kivimaki M., Deary I.J., Bell S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsch-Supan A., Brandt M., Hunkler C., Kneip T., Korbmacher J., Malter F., Schaan B., Stuck S., Zuber S. Data resource profile: the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:992–1001. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R., Shipley M., Lewington S., Youngman L., Collins R., Marmot M., Peto R. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999;150:341–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum R.M., Anthony J.C., Bassett S.S., Folstein M.F. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary I.J. Intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012;63:453–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary I.J., Batty G.D. Cognitive epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2007;61:378–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary I.J., Gale C.R., Stewart M.C., Fowkes F.G., Murray G.D., Batty G.D., Price J.F. Intelligence and persisting with medication for two years: Analysis in a randomised controlled trial. Intelligence. 2009;37:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detoc M., Bruel S., Frappe P., Tardy B., Botelho-Nevers E., Gagneux-Brunon A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine. 2020;38:7002–7006. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Loe B.S., Chadwick A., Vaccari C., Waite F., Rosebrock L., Jenner L., Petit A., Lewandowsky S., Vanderslott S., Innocenti S., Larkin M., Giubilini A., Yu L.M., McShane H., Pollard A.J., Lambe S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A., Littlejohns T.J., Sudlow C., Doherty N., Adamska L., Sprosen T., Collins R., Allen N.E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of UK Biobank Participants With Those of the General Population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017;186:1026–1034. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale C.R., Deary I.J., Batty G.D. Cognitive ability and risk of death from lower respiratory tract infection: findings from UK Biobank. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1342. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38126-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale C.R., Deary I.J., Wardle J., Zaninotto P., Batty G.D. Cognitive ability and personality as predictors of participation in a national colorectal cancer screening programme: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2015;69:530–535. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher, J., 2020. Covid-19: Oxford University vaccine is highly effective (BBC News). https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-55040635.

- Gottfredson L.S. Intelligence: is it the epidemiologists' elusive “fundamental cause” of social class inequalities in health? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004;86:174–199. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M., D’Ardenne, J., Balarajan, M., Uhrig, N., 2011. Cognitive testing of wave 3 understanding society questions. Institute for Social and Economic Research: University of Essex.

- Hankins M. The factor structure of the twelve item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): the result of negative phrasing? Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Mental Health. 2008;4:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K.M., Maurer J., Lurie N. Do people who intend to get a flu shot actually get one? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009;24:1311–1313. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holi M.M., Marttunen M., Aalberg V. Comparison of the GHQ-36, the GHQ-12 and the SCL-90 as psychiatric screening instruments in the Finnish population. Nord. J. Psychiatry. 2003;57:233–238. doi: 10.1080/08039480310001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert F.A., Brayne C., Gill C., Paykel E., Beardsall L. CAMCOG—A concise neuropsychological test to assist dementia diagnosis: Socio-demographic determinants in an elderly population sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;34:529–541. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuter, B.J., Browne, S., Momplaisir, F.M., Feemster, K.A., Shen, A.K., Green-McKenzie, J., Faig, W., Offit, P.A., 2021. Perspectives on the receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine: A survey of employees in two large hospitals in Philadelphia. Vaccine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lachman M.E., Agrigoroaei S., Murphy C., Tun P.A. Frequent cognitive activity compensates for education differences in episodic memory. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2010;18:4–10. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ab8b62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassale C., Gaye B., Hamer M., Gale C.R., Batty G.D. Ethnic disparities in hospitalisation for COVID-19 in England: The role of socioeconomic factors, mental health, and inflammatory and pro-inflammatory factors in a community-based cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Q., Cowling B.J., Lam W.W., Fielding R. Factors affecting intention to receive and self-reported receipt of 2009 pandemic (H1N1) vaccine in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall, S., 2013. Understanding Society: UK household longitudinal study: Cognitive ability measures. Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex.

- Murphy J., Vallières F., Bentall R.P., Shevlin M., McBride O., Hartman T.K., McKay R., Bennett K., Mason L., Gibson-Miller J., Levita L., Martinez A.P., Stocks T.V.A., Karatzias T., Hyland P. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisser U., Boodoo G., Bouchard Jnr T., Boykin A.W., Brody N., Ceci S.J., Halpern D.F., Loehlin J.C., Perloff R., Sternberg R.J., Urbina S. Intelligence: knowns and unknowns. Am. Psychol. 1996;51:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K.H., Srivastav A., Razzaghi H., Williams W., Lindley M.C., Jorgensen C., Abad N., Singleton J.A. COVID-19 Vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination - United States, September and December 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:217–222. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7006e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Conor R., Muellers K., Arvanitis M., Vicencio D.P., Wolf M.S., Wisnivesky J.P., Federman A.D. Effects of health literacy and cognitive abilities on COPD self-management behaviors: A prospective cohort study. Respir Med. 2019;160 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer S.B., Yildirim I., Forman H.P. Herd immunity and implications for SARS-CoV-2 control. JAMA. 2020;324:2095–2096. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M., Shipley B., Fuhrer R., Wadsworth M.E. Cognitive ability in childhood and cognitive decline in mid-life: longitudinal birth cohort study. BMJ. 2004;328:552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37972.513819.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie S.J., Hill W.D., Marioni R.E., Davies G., Hagenaars S.P., Harris S.E., Cox S.R., Taylor A.M., Corley J., Pattie A. Polygenic predictors of age-related decline in cognitive ability. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0372-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, E., Reeve, K.S., Niedzwiedz, C.L., Moore, J., Blake, M., Green, M., Katikireddi, S.V., Benzeval, M.J., 2021. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav. Immunity, 2020.2012. 2027.20248899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ruiz J.B., Bell R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ T., Hamer M., Stamatakis E., Starr J., Batty G. Psychological distress as a risk factor for dementia death. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011;171:1858–1859. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ T.C., Kivimaki M., Morling J.R., Starr J.M., Stamatakis E., Batty G.D. Association between psychological distress and liver disease mortality: a meta-analysis of individual study participants. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:958–966. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ T.C., Stamatakis E., Hamer M., Starr J.M., Kivimaki M., Batty G.D. Association between psychological distress and mortality: individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega A., Faul J.D., Ofstedal M.B., Langa K.M., Phillips J.W., Weir D.R. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43:576–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Breeze E., Banks J., Nazroo J. Cohort profile: the english longitudinal study of ageing. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:1640–1648. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.D., Hart C.L., Smith G.D., Starr J.M., Hole D.J., Whalley L.J., Wilson V., Deary I.J. Childhood IQ and social factors on smoking behaviour, lung function and smoking-related outcomes in adulthood: linking the Scottish Mental Survey 1932 and the Midspan studies. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2005;10:399–410. doi: 10.1348/135910705X25075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Essex, I.f.S.a.E.R., NatCen Social Research, Kantar Public, 2020. Understanding Society: Waves 1-10, 2009-2019 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 6614.

- University of Essex, I.f.S.a.E.R., NatCen Social Research, Kantar Public, 2021. Understanding Society: COVID-19 Study, 2020-2021. UK Data Service. SN: 8644.

- von Wagner C., Steptoe A., Wolf M.S., Wardle J. Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Educ. Behav. 2009;36:860–877. doi: 10.1177/1090198108322819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallert J., Lissåker C., Madison G., Held C., Olsson E. Young adulthood cognitive ability predicts statin adherence in middle-aged men after first myocardial infarction: a Swedish National Registry study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017;24:639–646. doi: 10.1177/2047487317693951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Jing R., Lai X., Zhang H., Lyu Y., Knoll M.D., Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8 doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley L., Fox H., Lemmon H., Duthie S., Collins A., Peace H., Starr J., Deary I. Dietary supplement use in old age: associations with childhood IQ, current cognition and health. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2003;18:769–776. doi: 10.1002/gps.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L., Flowers P., McLeod J., Young D., Rollins L. Social patterning and stability of intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in Scotland: Will those most at risk accept a vaccine? Vaccines. 2021;9:17. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.S., Serper, M., Opsasnick, L., O'Conor, R.M., Curtis, L.M., Benavente, J.Y., Wismer, G., Batio, S., Eifler, M., Zheng, P., Russell, A., Arvanitis, M., Ladner, D., Kwasny, M., Persell, S.D., Rowe, T., Linder, J.A., Bailey, S.C., 2020. Awareness, Attitudes, and Actions Related to COVID-19 Among Adults With Chronic Conditions at the Onset of the U.S. Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Survey. Annals of internal medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- YouGov, I.C.L., 2021. COVID-19 Behaviour Tracker. https://ichpanalytics.imperialcollegehealthpartners.com/t/BDAU/views/YouGovICLCOVID-19BehaviourTracker/4Allbehaviorsovertime?:iid=1&:isGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&:embed=y.