Abstract

SUMMARY: We describe the neuroradiologic findings in a 7-year-old boy with anomalous intracranial venous drainage and cerebral calcification. CT scans demonstrated that his scalp mass was a plexus of scalp veins filled through the emissary foramen, and there were cerebral calcifications. Angiography revealed bilateral sigmoid sinus atresia with most of the intracranial venous drainage via the prominent mastoid emissary veins into dilated scalp vein. The possible relationship between cerebral calcification and anomalous intracranial venous drainage is discussed.

Normally, most of the cerebral venous drainage collects ultimately into the transverse and sigmoid sinuses of the skull base, and the pathway from the dural sinuses of the posterior fossa into the internal jugular veins is anatomically obvious through the jugular foramen and numerous connections with the vertebral plexus.1,2

In this article, we present a very rare case of bilateral sigmoid sinus atresia with most of the cerebral venous drainage through the prominent mastoid emissary vein to a plexus of dilated scalp veins, presenting as a posterior auricular mass lesion and, more unusually, with a combination of basal ganglia and cerebral calcification.

Case Report

The patient was a 7-year-old boy who presented with a tender mass lesion in the left posterior auricular region and with left tinnitus. His parents first noticed the mass 2 years ago by accident, and the patient noticed left tinnitus 1 year ago. The mass had grown slowly during the past 2 years. The patient did not report nausea, vomiting, headache, or pain from the lesion. On his admission, physical examination revealed a fluctuant mass approximately 3 cm in diameter. Very soft thrill and bruit were noted on the surface of the mass. The mass disappeared when manually compressing the skull depression under the center of the mass. Physical examination showed no specific neurologic deficits. Neuropsychological testing, including Chinese translation of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Revised) and Chinese translation of the Wechsler Memory Scale for Children, suggested no impairment. Blood analyses for copper, coeruloplasmin, ferritin, calcium, and phosphorus levels, as well as thyroid and parathyroid profiles, were normal. Neurophysiologic studies, including an electroencephalogram and a determination of brain stem auditory-evoked potentials, were generally normal.

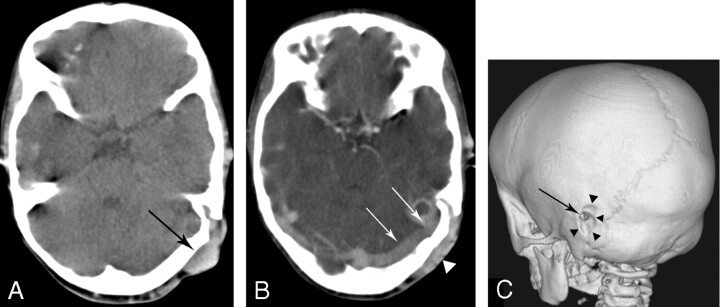

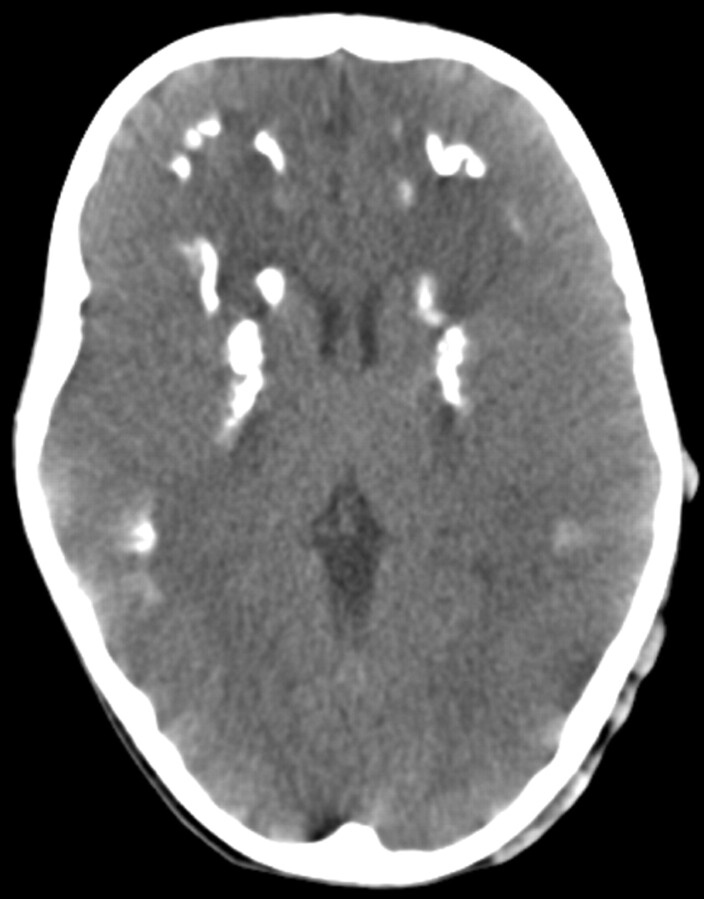

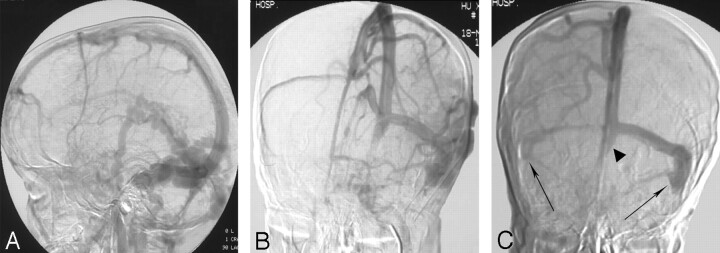

A CT scan suggested that the mass was a plexus of dilated scalp veins filled through the prominent mastoid emissary foramen (Fig 1). There were also diffuse calcifications on the bilateral basal ganglia and subcortical white matter in CT scan (Fig 2). Carotid artery angiography revealed grossly anomalous intracranial venous drainage (Fig 3). There was remarkable stenosis of the left transverse sinus and atresia of both sigmoid sinuses with florid collateral scalp vein drainage via the prominent mastoid emissary vein. Additionally, after manual compression of the mastoid emissary foramen, there was no other obvious collateral drainage passageway. On the basis of these findings, together with the normal growth and life of the patient, he was discharged with close follow-up.

Fig 1.

CT scan of the patient.

A, Noncontrast axial CT scan shows subcutaneous mass (arrow) and local skull defect on the upper portion of the petrous bone.

B, Contrast axial CT scan shows that the enhanced subcutaneous mass (arrow) is communicated with the lateral sinus (arrowheads) through the skull defect, which suggests that the mass lesion is dilated scalp veins filled through the prominent mastoid emissary foramen.

C, 3D CT-shaded surface display showing enlargement of the outer opening of the mastoid emissary foramen (arrow) and depression of the skull surface (arrowheads) around it.

Fig 2.

Noncontrast axial CT scan shows diffuse calcification on the bilateral basal ganglia and subcortical white matter.

Fig 3.

Digital subtraction angiogram.

A and B, Venous phase of left internal carotid artery angiogram in lateral view (A) and anterioposterior view (B) demonstrate nonopacification of right transverse sinus and left sigmoid sinus. There are tortuous collateral scalp veins via the enlarged mastoid emissary vein.

C, Late venous phase of internal carotid artery angiogram in lateral view with manual compressing of the outer opening of the mastoid emissary foramen shows marked narrowing of left transverse sinus and atresia of bilateral sigmoid sinus (arrow) and occipital sinus (arrowheads), suggesting the venous drainage of intracanial structures are mainly throught the mastoid emissary vein.

Discussion

Occlusion of the bilateral transverse-sigmoid sinus is rare, which may be idiopathic or caused by various disorders such as thrombosis and syndromic craniosynostoses.3-5 Anatomic and radiologic studies6 have shown extensive extracranial collateral drainage networks in the posterior fossa dural sinus via condylar/mastoid/occipital emissary veins, diploic veins, and marginal/occipital sinuses, and these studies have shown that the morphologic changes of the posterior fossa dural sinuses, emissary veins, and jugular bulb are closely related to development of the brain, shifts to postnatal types of circulation, and to postural hemodynamic changes. A MR venography study7 also showed multiple variants of intracranial venous drainage, including a patient absent of both transverse sinuses whose occipital sinuses were present on both sides, serving as alternative drainage pathways from torcular herophili to internal jugular veins. The etiology of the bilateral sigmoid sinus occlusion in this patient was unknown. He had no history of mastoiditis, meningitis, or head trauma. Also no sign of craniosynostoses was seen on CT scans. Thus, despite the lack of initial angiographic findings, we presumed that our patinet’s mass was from developmental morphologic anomalies.

When there is atresia at the bilateral sigmoid sinus or transverse sinus, venous drainage may occur via 2 routes: 1) by collateral emissary veins or, if absent, by the marginal/occipital sinus; or 2) by anterior drainage into the Galenic system or into the superior sagittal sinus and cavernous sinus.8,9 Cases with anomalous intracranial venous drainage present various manifestations depending on the different drainage routes. Tech et al9 reported a case of bilateral sigmoid sinus hypoplasia/aplasia with most of the cerebral venous drainage occurring through the right cavernous sinus and diploic emissary veins. The patient presented with swelling of the right eye and bluish discoloration over the periorbital region, mimicking a cavernous arteriovenous fistula. In our patient, anomalous intracranial venous drainage collected into dilated plexus of scalp veins via unilateral prominent mastoid emissary veins, mimicking a posterior auricular mass lesion.

Our patient was even more unusual in that he had bilateral (almost symmetrical) calcification involving basal ganglia and cerebral white matter. Brain calcification could be autosomal-dominant, family based, or secondary to a variety of developmental, metabolic, infectious, and other conditions.10 In the case of secondary causes, the major differential diagnosis is hypoparathyroidism. The exact mechanism of the cerebral calcification for our patient was unknown. He had no history of head trauma or cerebral chemoradiotherapy, and the obtained serum calcium and parathyroid hormone levels were normal. When considering the differential diagnosis in a patient with venous drainage abnormalities and intracranial calcification, considerations include Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), in which cerebral calcification and atrophy develop as a result of leptomeningeal angiomatous malformation and poor superficial cortical venous drainage. The representative radiologic features of SWS,11,12 such as lack of superficial cortical veins, enlarged regional transmedullary veins, parenchymal atrophy, and gyriform calcifications, were not found in our patient. Additionally, patients with SWS may have clinical findings such as facial cutaneous vascular malformation, seizures, glaucoma, transient strokelike neurologic deficits, and behavioral problems.13 Our patient had none of these symptoms or physical signs described previously.

The previously listed disorders are not likely, and we therefore considered whether our patient’s cerebral calcification might be related to the anomalous intracranial venous drainage. Cerebral calcification has been reported in patients with dural arteriovenous fistula and has been proposed to be an arterial steal phenomenon or persistent venous congestion that occurs in chronic hypoperfused brain parenchyma or secondary to dystrophic changes in the walls of congested veins.14,15 The basal ganglia and cerebral subcortical white matter regions are located in the watershed areas of the arterial supply and therefore are more sensitive to hypoxic or ischemic changes. In our patient, information concerning the initial status and development of collateral venous drainage was not available. However, an analysis of children with craniosynostosis16 indicated that the period of particular vulnerability to the effects of venous hypertension caused by abnormal intracranial venous drainage lasts until the affected child is approximately 6 years old, when collateral venous drainage through the stylomastoid plexus likely becomes sufficient. We therefore presumed that initial insufficient collateral venous drainage and chronic venous congestion may have existed despite the existence of florid collateral routes. Interruption of collateral emissary and superficial scalp veins in such cases may induce venous hypertension and should be taken into account in surgery. Thompson el al17 reported an important lesson during surgery on a patient with cloverleaf skull syndrome. During cranial vault remodeling surgery in their patient, unavoidable division of the emissary occipital veins for collateral drainage led to an acute and fatal rise in intracranial pressure. On the basis of radiologic findings of sufficient and normal neurologic development of our patient, no surgical procedure is considered.

In summary, our case was unusual because the anomalous intracranial venous drainage in our patient was mainly through the unilateral prominent emissary vein and dilated scalp veins, and he presented with a scalp mass lesion. We think that anomalous intracranial venous drainage associated with intracranial calcification as found in our patient has not been reported previously. Dilated collateral scalp veins should be included in the differential diagnosis of scalp lesions, especially before surgical procedures.

References

- 1.Hacker H. Superficial supratentorial veins and dural sinuses. In: Potts DG, Newton TH, eds. Radiology of the Skull and Brain, vol. 2. St Louis: The CV Mosby Company;1974. :1851–77

- 2.San Millan Ruiz D, Gailloud P, Rufenacht DA, et al. The craniocervical venous system in relation to cerebral venous drainage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002;23:1500–08 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KR Jr. Idiopathic bilateral sigmoid sinus occlusion in a child: case report. J Neurosurg 1968;29:427–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sindou M, Mercier P, Bokor J, et al. Bilateral thrombosis of the transverse sinuses: microsurgical revascularization with venous bypass. Surg Neurol 1980;13:215–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson CD, Mulliken JB, Robertson RL, et al. Prominent basal emissary foramina in syndromic craniosynostosis: correlation with phenotypic and molecular diagnoses. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1707–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okudera T, Huang YP, Ohta T, et al. Development of posterior fossa dural sinuses, emissary veins, and jugular bulb: morphological and radiologic study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:1871–83 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widjaja E, Griffiths PD. Intracranial MR venography in children: normal anatomy and variations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1557–62 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YP, Ohta T, Okudera T, et al. Anatomic variations of the dural venous sinuses. In: Kapp JP, Schmidek HH, eds. The Cerebral Venous System and Its Disorders. Orlando, Fla: Grune & Stratten;1984. :109–67

- 9.Tech KE, Becker CJ, Lazo A, et al. Anomalous intracranial venous drainage mimicking orbital or cavernous arteriovenous fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:171–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manyam BV. What is and what is not ‘Fahr’s disease’. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2005;11:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Probst FP. Vascular morphology and angiographic flow patterns in Sturge-Weber angiomatosis: facts, thoughts and suggestions. Neuroradiology 1980;20:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marti-Bonmati L, Menor F, Mulas F. The Sturge-Weber syndrome: correlation between the clinical status and radiological CT and MRI findings. Childs Nerv Syst 1993;9:107–09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas-Sohl KA, Vaslow DF, Maria BL. Sturge-Weber syndrome: a review. Pediatr Neurol 2004;30:303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai PH, Chang MH, Liang HL, et al. Unusual signs for dural arteriovenous fistulas with diffuse basal ganglia and cerebral calcification. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 2000;63:329–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang MS, Chen CC, Cheng YY, et al. Unilateral subcortical calcification: a manifestation of dural arteriovenous fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005;26:1149–51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor WJ, Hayward RD, Lasjaunias P, et al. Enigma of raised intracranial pressure in patients with complex craniosynostosis: the role of abnormal intracranial venous drainage. J Neurosurg 2001;94:377–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson DN, Hayward RD, Harkness WJ, et al. Lessons from a case of kleeblattschadel. Case report. J Neurosurg 1995;82:1071–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]