Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: The purpose of this work was to assess intertechnique and interobserver reproducibility of 64-row multisection CT angiography (CTA) used to detect and evaluate intracranial aneurysms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS: From October 2005 to November 2006, 54 consecutive patients with nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) underwent both CTA and digital substraction angiography (DSA). Four radiologists independently reviewed CT images, and 2 other radiologists reviewed DSA images. Aneurysm diameter (D), neck width (N), and the presence of a branch arising from the sac were assessed.

RESULTS: DSA revealed 67 aneurysms in 48 patients and no aneurysm in 6 patients. Mean sensitivity and specificity of CTA for the detection of intracranial aneurysms were, respectively, 94% and 90.2%. For aneurysms less than 3 mm, CTA had a mean sensitivity of 70.4%. Intertechnique and interobserver agreements were good for the detection of aneurysms (mean κ = 0.673 and 0.732, respectively) and for the measurement of their necks (mean κ = 0.753 and 0.779, respectively). Intertechnique and interobserver agreements were excellent for the measurement of aneurysm diameters (mean κ = 0.847 and 0.876, respectively). In addition, CTA was accurate in determining the N/D ratio of aneurysms and adjacent arterial branches. However, the N/D ratio was overestimated by all of the readers at CTA.

CONCLUSION: Sixty-four-row multisection CTA is an imaging method with a good interobserver reproducibility and a high sensitivity and specificity for the detection and the morphologic evaluation of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. It may be used as an alternative to DSA as a first-intention imaging technique in patients with SAH.

Rupture of an intracranial aneurysm causing subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) occurs with an incidence of between 6 and 8 per 100,000 in most Western populations.1 Mortality is high among patients with this condition, and prompt detection and evaluation of the aneurysm is critical for determining the appropriate endovascular or neurosurgical intervention. Digital substraction angiography (DSA) is currently the standard method for detection and evaluation of intracranial aneurysms.2 However, this method is invasive, time consuming, relatively expensive, and associated with a 0.5% risk of permanent neurologic complications.3 CT angiography (CTA) has increasingly been recognized as an efficient noninvasive imaging method in the evaluation of patients with suspected intracranial aneurysms. The reported sensitivity of single- and multidetector row CTA is in the range of 67%–98% depending on the size and location of the aneurysm.4–18 A recently published series has shown that multidetector row CT scanners have higher sensitivity than single-detector row CT scanners for the detection of intracranial aneurysms. However, only a few studies have evaluated the ability of CTA to characterize intracranial aneurysms to choose endovascular treatment (EVT) and surgical clipping.12–16 Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is only 1 study that has evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of 64-row multisection CTA for the detection and the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms.13 This latter study and most of the previously published ones have not evaluated the reproducibility of multisection CTA between observers. The aim of our study was, thus, to assess interobserver and intertechnique reproducibility of 64-row multisection CTA used to detect and evaluate intracranial aneurysms.

Patients and Methods

Population

Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained for this study. We reviewed the files of all of the patients who underwent both 64-row multisection CTA and DSA for nontraumatic SAH indicated by imaging findings at nonenhanced CT scan. Between October 2005 and November 2006, 54 patients were identified and included in the study. The 54 patients included 37 women and 17 men ranging in age from 18 to 85 years, with an average age of 55 years. Patients were graded according to the Hunt and Hess scale: 44 patients were graded 1 or 2, 3 were graded 3, and 7 were graded 4 or 5.19

Imaging

For their initial diagnostic evaluation and to choose appropriate treatment, all of the patients underwent CTA with a 64-row multisection CTA (Somaton Sensation 64; Siemens Medical Systems, Forcheim, Germany). All of the CT images were diagnostic, and there were no technical failures or complications during scanning. Patients were examined in supine position, and a lateral 26-cm scout view was first obtained at 120 kVp and 35 mA. This was followed by a 12-cm-high helical CTA acquisition in craniocaudal direction from the top of the frontal sinusal cavities to the second cervical vertebral body, with a detector collimation of 32 × 0.6 mm, rotation time of 0.5 seconds, pitch of 1, 100 kVp, and 200 effective milliamps, resulting in a CT dose index of 18.95 mGy and a dose-length product of 300 mGy.cm. As recommended by the manufacturer during acquisition in head mode, automatic exposure control device was not enabled. Each CTA acquisition was performed with intravenous injection of 80 mL of iodinated contrast material (iobitridol, Xenetix 350 [350 mg of iodine/mL]; Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) at 4 mL/s and with an imaging start delay determined by a bolus tracking facility and a threshold fixed at 100 Hounsfield units. From the raw data acquired, 0.75-mm-thick transversal sections were reconstructed with 0.4-mm increments. Reconstructed images were stored on compact discs and, for the purpose of the present study, were read on a clinical workstation with a multiplanar reformation, maximum intensity projection, and volume rendering technique display (Leonardo; Siemens Medical Systems). The radiologists could manipulate the images in a near-infinite number of projections with various amounts of time needed for review. The total examination time for CTA was approximately 10 minutes per case.

The etiologic diagnosis of SAH was confirmed by DSAs that were performed with femoral catheterization with a single (Angiostar; Siemens Medical Systems) or a biplane (Allura Xper 20/10; Philips, Best, the Netherlands) DSA unit. Three- or 4-vessel studies were obtained with standard frontal, lateral, and oblique views. Then, rotational spin angiograms with 3D reconstructions were obtained to avoid the limitation of 2D-DSA described in other articles.7–10,16–18 Therefore, our DSA protocol was considered as the “gold standard.” All of the DSA examinations were performed within 24 hours after CTA. If EVT or a surgical clipping was scheduled, DSA was performed before (surgical clipping) or at the beginning of EVT. Whenever the initial CTA was negative or did not provide enough information to choose the appropriate treatment, DSA was performed.

Image Interpretation

CTA and DSA images were independently interpreted by 6 radiologists (B.L., D.B., O.F., P.T., L.C., N.S.): 1 fellow in the last year of radiology fellowship (P.T.) and 5 senior neuroradiologists with 30 (D.B.), 15 (L.C.), 9 (N.S.), 6 (B.L.), and 4 years of experience (O.F.) in vascular diagnostic neuroradiology.

Four radiologists (O.F., reader 1; P.T., reader 2; L.C., reader 3; N.S., reader 4) retrospectively interpreted CTA images to detect and evaluate intracranial aneurysms. If an aneurysm was detected, several morphologic characteristics were evaluated: the aneurysm maximal diameter (D) and neck (N) were measured, and the presence of a branch arising from the sac was noted. All of the measures were performed on the workstation with an electronic caliper after appropriate magnification; the aneurysm diameter and neck dimensions were measured at a selected projection, which allowed the optimal demonstration of the neck of the aneurysm. Based on most of the previously published series,7,8,11,17,18 we have classified aneurysm diameter into 3 groups: less than 3 mm (group A), from 3 to 10 mm (group B), and more than 10 mm (group C). For an easier understanding of the results and the statistical analysis, we have classified aneurysms neck into 3 groups: less than 2 mm (group 1), from 2 to 4 mm (group 2), and more than 4 mm (group 3). For each detected aneurysm, N/D ratio was then calculated both on DSA and CTA images. Finally we asked our readers to note whether they were encountering a classic drawback to CTA,5–12 which is its tendency to “smooth” vessels adjacent to the neck into the wall of the aneurysm. CTA readers performed their readings independently, each being blinded to the results of the other's readings and DSA.

All of the DSAs were performed by an interventional neuroradiologist (B.L.) who performed all of the endovascular procedures as well. DSA images were interpreted by 2 neuroradiologists together (B.L. and D.B.).

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, 2 × 2 tables of the true-positive, false-positive, true-negative, and false-negative cases of cerebral aneurysms at CTA, using consensus interpretations of DSA as the standard of reference, were constructed. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of CTA for detection of aneurysms were calculated on both a per-aneurysm and a per-patient basis. The same 4 neuroradiologists with knowledge of the DSA findings retrospectively reviewed lesions that were considered false-positive or false-negative findings at the blinded review of the CTA images, and a consensus judgment was made as to the cause of the false-positive or false-negative results.

Interobserver agreement between readers and intertechnique agreement between CTA and DSA were determined by calculating κ statistics: poor agreement, κ = 0; slight agreement, κ = 0.01–0.20; fair agreement, κ = 0.21–0.40; moderate agreement, κ = 0.41–0.60; good agreement, κ = 0.61–0.80; and excellent agreement, κ = 0.81–1.00. The relationships between the N/D ratio by CTA and DSA were compared using linear regression and the Pearson correlation coefficient (R). P < .05 was considered significant. All of the statistical analyses were performed with commercially available software (SPSS 10.0 for Window; SPSS; Chicago, Ill).

Results

Etiologic Diagnosis of SAH

Of the 54 patients with SAH and DSA, 48 had aneurysmal SAH, 2 had a vertebral artery dissection, 1 had vasculitis, and 3 had no proved underlying arterial abnormality (1 diagnosed as perimesencephalic SAH and 2 with no detected reason for SAH). Reader 4 made correct diagnosis with CTA in all of the patients, whereas the other 3 readers made correct diagnosis in 53 of 54 patients. These 3 readers missed on CTA the diagnosis of vasculitis in the same patient. Concerning the detection of ruptured aneurysms, all of the CTA readers identified the culprit aneurysm in all 48 of the patients with SAH from an aneurysmal origin.

Aneurysm Detection

A total of 67 aneurysms in 48 patients were identified at DSA. Six patients had 2 aneurysms, 3 patients had 3 aneurysms, 1 patient had 4 aneurysms, and 1 patient had 5 aneurysms.

Diagnostic performance of CTA for aneurysms detection is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Of 67 aneurysms, reader 1 identified 62 aneurysms; reader 2 identified 63 aneurysms; reader 3 identified 63 aneurysms; and reader 4 identified 64 aneurysms. On a per-aneurysm basis, CTA sensitivity and specificity for aneurysms detection varied, respectively, from 92.5% to 95.5% (mean = 94%) and from 75% to 100% (mean = 90.2%). However, on a per-patient basis, all of the CTA readers achieved a sensitivity and specificity of 100%. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were also calculated according to the size of the aneurysm (Table 2). The sensitivity of CTA for the detection of aneurysms less than 3 mm varied from 63.6% to 81.8% (mean = 70.4%); for aneurysms at or more than 3 mm, the CTA sensitivity ranged from 96.4% to 100% (mean = 98.7%). Details of all of the false-negative and false-positive results of CTA are listed in Table 3.

Table 1:

Aneurysm detection: diagnostic performance of CT angiography on a per-aneurysm basis

| Reader | Sensitivity, % (n/N) | Specificity, % (n/N) | Positive Predictive Value, % (n/N) | Negative Predictive Value, % (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reader 1 | 92.5 (62/67) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (62/62) | 54.5 (6/11) |

| Reader 2 | 94 (63/67) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (63/63) | 60 (6/10) |

| Reader 3 | 94 (63/67) | 85.7 (6/7) | 98.4 (63/64) | 60 (6/10) |

| Reader 4 | 95.5 (64/67) | 75 (6/8) | 97 (64/66) | 66.7 (6/9) |

Note:—Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of aneurysms.

Table 2:

Diagnostic performance of CT angiography according to aneurysm size

| Aneurysm Size | Sensitivity, % (n/N) | Specificity, % (n/N) | Positive Predictive Value, % (n/N) | Negative Predictive Value, % (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 mm | ||||

| Reader 1 | 63.6 (7/11) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (7/7) | 60 (6/10) |

| Reader 2 | 81.8 (9/11) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (9/9) | 75 (6/8) |

| Reader 3 | 63.6 (7/11) | 85.6 (6/7) | 87.5 (7/8) | 60 (6/10) |

| Reader 4 | 72.7 (8/11) | 85.6 (6/7) | 88.8 (8/9) | 66.7 (6/9) |

| ≥3 mm | ||||

| Reader 1 | 98.2 (55/56) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (55/55) | 85.6 (6/7) |

| Reader 2 | 96.4 (54/56) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (54/54) | 75 (6/8) |

| Reader 3 | 100 (56/56) | 100 (6/6) | 100 (56/56) | 100 (6/6) |

| Reader 4 | 100 (56/56) | 85.6 (6/7) | 98.2 (56/57) | 100 (6/6) |

Note:—Numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of aneurysms.

Table 3:

Aneurysm detection: characteristics of false-negative and false-positive evaluations

| Aneurysm Location | Size, mm | Reader | Main Reason for Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| False-negative | |||

| Basilar tip | 1.5 | 1, 3 | Very small, multiple aneurysms |

| AchoA | 1 | All readers | Very small |

| PcomA | 3 | 2 | Considered as an infundibulum |

| Carotid-ophthalmic ICA | 2 | 3 | Very small, multiple aneurysms |

| Paraclinoid ICA | 3 | 1, 2 | Small, close to bony structures |

| MCA: M2 segment | 2 | All readers | Very small, unusual location |

| MCA bifurcation | 2 | 1 | Very small, multiple aneurysms |

| MCA bifurcation | 2 | 4 | Very small, obscured by overlapping vessels |

| False-positive | |||

| ACA: A2 segment | 2 | 3 | Vasculitis |

| PcomA | 2 | 4 | Prominent infundibulum |

| PcomA | 3 | 4 | Prominent infundibulum |

Note:—AchoA indicates anterior choroidal artery; PcomA, posterior communicating artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; ACA, anterior cerebral artery.

All of the missed aneurysms were at or less than 3 mm in diameter. Nevertheless, all of the ruptured aneurysms with a diameter less than 3 mm (n = 3) were detected by all of the readers. Moreover, all of the missed aneurysms were in patients with multiple aneurysms in whom the ruptured aneurysm was correctly identified by all of the readers at the CTA reading. All of the missed aneurysms were visible, by consensus of the 4 readers, when the CTA images were viewed retrospectively in conjunction with DSA images. There were 3 false-positive findings in 3 patients at CTA. In 2 patients, a posterior communicating artery (PcomA) aneurysm was described on CTA by reader 4, but with DSA, there were infundibular dilations at the origin of the PcomA. In the third patient, a small aneurysm distally located on an anterior cerebral artery was described on CTA by reader 3, but with DSA, there was a cerebral vasculitis without evidence of aneurysm.

The interobserver and intertechnique agreements for the detection of intracranial aneurysms are detailed in Table 4. The intertechnique agreement (mean κ = 0.673) was good for readers 1–3 (κ = 0.671–0.721) and moderate for reader 4 (κ = 0.578). The interobserver agreement was good to excellent for all of the readers (κ = 0.622–0.833; mean κ = 0.732).

Table 4:

Aneurysm detection: interobserver and intertechnique agreements

| Reader | CTA Reader 1 | CTA Reader 2 | CTA Reader 3 | CTA Reader 4 | DSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTA reader 1 | – | κ = 0.833 | κ = 0.833 | κ = 0.622 | κ = 0.671 |

| CTA reader 2 | κ = 0.833 | – | κ = 0.768 | κ = 0.668 | κ = 0.721 |

| CTA reader 3 | κ = 0.833 | κ = 0.768 | – | κ = 0.668 | κ = 0.721 |

| CTA reader 4 | κ = 0.622 | κ = 0.668 | κ = 0.668 | – | κ = 0.578 |

Note:—CTA indicates computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital substraction angiography; –, no data.

Aneurysm Characteristics

On DSA images, aneurysms size ranged from 1 to 21 mm (mean size = 5.1 mm). Eleven aneurysms were classified in group A, 45 aneurysms in group B, and 11 aneurysms in group C. The smallest aneurysm detected by CTA in this study was an unruptured 1-mm basilar tip aneurysm. The smallest ruptured aneurysm detected by CTA (Fig 1) was a ruptured 1.5-mm aneurysm located at the junction between the A2 segment from the right anterior cerebral artery and a second fenestrated anterior communicating artery (AcomA).

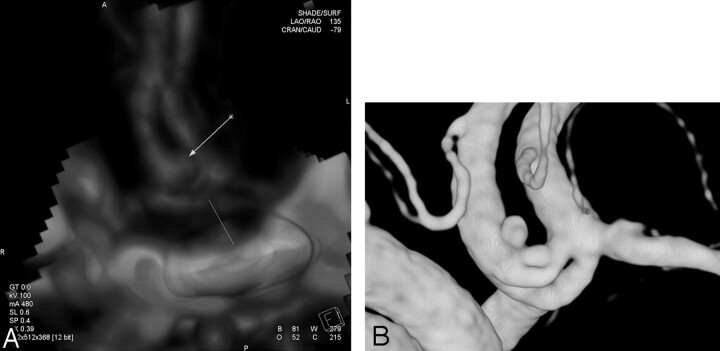

Fig 1.

Images obtained in a 49-year-old woman with SAH. A, 3D volume-rendered CTA image in lateral view shows a 1.5-mm ruptured aneurysm (arrow) at the junction between the A2 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery and a second anterior communicating artery that is fenestrated (line). B, Lateral projection from presurgical treatment 3D DSA shows the same aneurysm as in A.

The interobserver and intertechnique agreements for the measurement of aneurysm maximal diameter are detailed in Table 5. Both the intertechnique (κ = 0.823–0.883; mean κ = 0.847) and the interobserver (κ = 0.826–0.916; mean κ = 0.876) agreements were excellent for all of the readers. On DSA images, aneurysm necks were classified in 3 groups: 8 were classified in group 1, 49 were classified in group 2, and 10 were classified in group 3.

Table 5:

Aneurysm maximal diameter measurement: interobserver and intertechnique agreements

| Reader | CTA reader 1 | CTA reader 2 | CTA reader 3 | CTA reader 4 | DSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTA reader 1 | – | κ = 0.858 | κ = 0.916 | κ = 0.888 | κ = 0.829 |

| CTA reader 2 | κ = 0.858 | – | κ = 0.855 | κ = 0.826 | κ = 0.823 |

| CTA reader 3 | κ = 0.916 | κ = 0.855 | – | κ = 0.914 | κ = 0.854 |

| CTA reader 4 | κ = 0.888 | κ = 0.826 | κ = 0.914 | – | κ = 0.883 |

Note:—CTA, computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital substraction angiography; –, no data.

The interobserver and intertechnique agreements for the measurement of aneurysm necks are detailed in Table 6. The intertechnique agreement was good for all of the readers (κ = 0.732–0.778; mean κ = 0.753). The interobserver agreement was good to excellent for all of the readers (κ = 0.693–0.856; mean κ = 0.779).

Table 6:

Aneurysm neck measurement: interobserver and intertechnique agreements

| Reader | CTA reader 1 | CTA reader 2 | CTA reader 3 | CTA reader 4 | DSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTA reader 1 | – | κ = 0.788 | κ = 0.856 | κ = 0.795 | κ = 0.778 |

| CTA reader 2 | κ = 0.788 | – | κ = 0.725 | κ = 0.693 | κ = 0.732 |

| CTA reader 3 | κ = 0.856 | κ = 0.725 | – | κ = 0.815 | κ = 0.768 |

| CTA reader 4 | κ = 0.795 | κ = 0.693 | κ = 0.815 | – | κ = 0.734 |

Note:—CTA, computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital substraction angiography; –, no data.

On DSA images, mean N/D ratio was 0.56. There was a strong positive correlation between N/D ratio measured at CTA and at DSA for all of the readers (R varied from 0.977 to 0.988; P varied from .0001 to .0005). However, all of the CTA readers overestimated the N/D ratio by 0.052 (range, 0.047–0.061; P = .0005) for an N/D ratio ranging from 0.58 to 0.61.

On DSA images, there were 4 aneurysms that presented with a branch arising from the sac. All of the branches were identified on CTA images by readers 3 and 4. Reader 1 failed to describe only 1 branch, whereas reader 2 failed to describe 3 branches.

Finally, all of the CTA readers described its tendency to “smooth” vessels adjacent to the neck into the wall of the aneurysm in the same 3 cases. These aneurysms were located on the AcomA (n = 2) and on the middle cerebral artery (MCA) bifurcation (n = 1). All of the other adjacent branches could be depicted precisely by all of the readers.

Treatment Choice Based on CTA Images

In 48 patients, SAH was caused by a ruptured aneurysm. One patient who presented with a Hunt and Hess grade 419 SAH and several other comorbidities had not been treated. Among 47 treated patients, therapeutic options could be discussed and chosen by the neurovascular team in all of the cases without the need for DSA. Thirty-nine patients were referred for EVT, and 8 patients were referred for surgical clipping. In this study, we regarded successful coiling as proof that a correct treatment decision was made. Successful EVT was achieved in 37 (94.9%) of the 39 patients. One patient presented with a distal aneurysm on a posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) with an extracranial origin. Because of this anatomic variation, the PICA course presented with multiple loops that prevented a safe catheterization of the aneurysm. The other patient had a ruptured AcomA aneurysm with an associated internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis that was demonstrated on the pre-embolization DSA and that was judged as a contraindication for EVT. These latter 2 patients were referred for surgical clipping.

Discussion

This study shows a good interobserver and intertechnique reproducibility of 64-row multisection CTA used to detect and evaluate ruptured intracranial aneurysms. CTA appeared very useful to identify the SAH cause, and it also allowed for precise depiction of aneurysm morphology that is mandatory to promptly choose the appropriate treatment (EVT versus surgical clipping). Therefore, CTA may be used as an alternative to DSA as first-intention imaging technique in patients with SAH.

Diagnosis of Underlying Etiology of SAH Using CTA

Patients with SAH are generally in poor clinical condition that may include strong headaches, confusion, neurologic deficits, and even coma. DSA remains the reference method for SAH diagnostic evaluation, but it is invasive, time consuming, and, thus, more difficult to perform in patients with such a condition.2 Moreover, DSA is associated with a 0.5% risk of permanent neurologic complications.3 Therefore, noninvasive techniques, such as CTA, have been developed and are increasingly recognized as alternatives to DSA. However, these techniques must have a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity close to DSA if they have to be used as first-intention diagnostic methods in the future. Indeed, SAH is an emergency situation that requires prompt and precise etiologic diagnosis to appropriately and quickly treat the patient.

In our study, 3 CTA readers diagnosed the cause of SAH in all of the patients but 1 who had a vasculitis. The fourth reader made a correct diagnosis in all of the patients. Furthermore, in 48 patients with an aneurysmal SAH, the culprit aneurysm was identified in all of the cases by all of the readers. Therefore, in our institution, CTA has replaced DSA as a first-intention diagnostic technique for patients with SAH. These findings are in agreement with a recently published series.11,13,15,16 However, if CTA is considered normal, DSA is still performed, even in the case of perimesencephalic SAH. In this latter situation, we anticipate that, in the near future, CTA will replace DSA as suggested by the recent study by Kershenovich et al.20

Aneurysm Detection

Several authors have shown that CTA has high sensitivity and specificity to detect intracranial aneurysms.4,14–16 A recent series, concerning CTA with multidetector row scanner, reported sensitivity between 95.1% and 98% and specificity of 100% for the detection of intracranial aneurysms.11,13,15–17 In our study, these findings were confirmed as our readers reached a mean sensitivity and specificity of 94% and 90.2%, respectively. It is of interest to pinpoint that, despite a difference between the readers’ experience in vascular neuroradiology, there was no significant difference between their ability to detect intracranial aneurysms on CTA. All of the missed aneurysms were at or less than 3 mm in diameter, and all of the ruptured aneurysms with a diameter less than 3 mm (n = 3) were detected by all of the readers. Moreover, all of the missed aneurysms were in patients with multiple aneurysms in whom the ruptured aneurysm was correctly identified by all of the readers at the CTA reading. Thus, all of the aneurysms missed by the readers in our study were incidental, noncausative aneurysms. These findings are also in agreement with the published series that showed that the sensitivity of CTA for the detection of aneurysms less than 3 mm remains inferior to DSA.10–17 In these series, most authors have suggested that CT scanners with 64-detector rows would improve the sensitivity and specificity of CTA. However, in our study, the sensitivity of CTA for the detection of aneurysms less than 3 mm varied from 63.6% to 81.8% (mean = 70.4%). Thus, our study does not show a superiority of 64-row multisection CTA over these previously published series that have evaluated 4- or 16-row multisection CTA.8–17 This well-known limited diagnostic accuracy of CTA in the detection of aneurysms less than 3 mm, thus, remains present with 64-row multisection CTA. Therefore, DSA remains slightly superior over CTA, and it is still performed in our institution in cases of SAH with negative findings on CTA.

The other well-known limitation of CTA for aneurysm detection concerns PcomA aneurysms and aneurysms located close to bony structures, such as paraclinoid aneurysms.6,8,16,21,22 In our study, false-negative results in 2 cases and false-positive results in 2 cases were related to aneurysms in such locations. This limitation is due to the close relationship with the posterior clinoid process and similar morphologic features with infundibular dilations, which made their discrimination difficult. Therefore, we believe that considerable caution is required in the interpretation of small aneurysms (<3 mm) arising from the PcomA or the paraclinoid ICA at CTA. To potentially circumvent this limitation, a new technique of substracted CTA has recently been developed and showed its efficacy for the evaluation of aneurysms located close to the skull base.21,22 This new method is increasing the sensitivity of CTA and is currently under evaluation in our institution.

Aneurysm Characterization

Three characteristics, which we considered mandatory to choose the appropriate treatment, were defined for each aneurysm, including the aneurysm maximal diameter, the neck width, and the presence of branch arising from the sac. All of the CTA readers correctly evaluated these aneurysmal characteristics in most cases (Figs 2 and 3). Indeed, for aneurysm maximal diameter measurement, the intertechnique agreement was excellent for all of the CTA readers (κ = 0.823–0.883). For aneurysm neck measurement, the intertechnique agreement was good for all of the CTA readers (κ = 0.732–0.778). However, concerning the evaluation of a possible branch arising from the sac, reader 2 failed to identify these branches in 3 of 4 cases. This difference with the other 3 readers might be explained by the fact that reader 2 is the less-experienced radiologist. Nevertheless, the crucial role of a general radiologist is to detect the ruptured aneurysm rather than describe its precise morphologic characteristics. Indeed, in the process of deciding whether to coil or to clip an aneurysm, CTA images are reviewed by the neurovascular team that must include a neurointerventionalist and a vascular neurosurgeon so that a precise evaluation of aneurysm characteristics is always performed by experienced physicians.

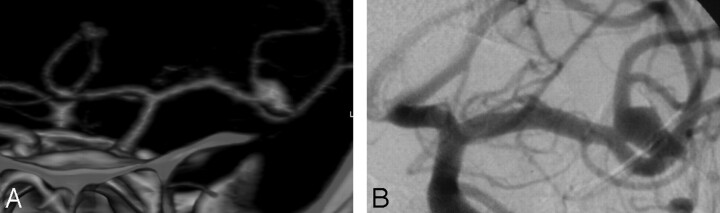

Fig 2.

Images obtained in a 48-year-old man with SAH. A, 3D volume-rendered CTA image in frontal view shows a left-ruptured MCA bifurcation aneurysm. The relationship between the aneurysm neck and the MCA bifurcation branches is clearly seen on CTA images. B, Frontal projection from pre-embolization DSA, performed with contrast material injection into the left ICA, shows the same aneurysm as in A.

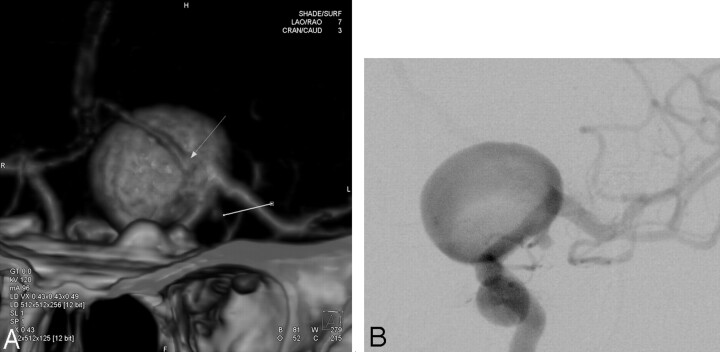

Fig 3.

Images obtained in a 64-year-old woman with SAH. A, 3D volume-rendered CTA image in frontal view shows 2 aneurysms: a large left-ruptured ICA bifurcation aneurysm with the A1 segment from the anterior cerebral artery arising from the sac (arrow) and a small left unruptured posterior communicating artery aneurysm (line). B, Frontal projection from pre-embolization DSA shows the same aneurysms as in A.

Concerning the N/D ratio, we found a strong and positive correlation between the N/D ratio measured at CTA and at DSA for all of the readers (R varied from 0.977 to 0.988; P varied from .0001 to .0005). However, all of the CTA readers overestimated the N/D ratio by 0.052, and this trend reached a statistical significance (range, 0.047–0.061, P = .0005). These results are in agreement with previous series.9,16 N/D ratio of aneurysm is important because it may affect the selection of the treatment options, and, in such cases, additional processing with the use of a virtual endoscopic image may reduce potential errors in the measurement of N/D ratio. Finally, our results also suggest that CTA can provide valuable information concerning the relationship between aneurysms and adjacent branches. In our series, the origin of adjacent branches was well demonstrated in all of the patients (Fig 2). However, in the same 3 patients with AcomA or MCA bifurcation aneurysms, all of the CTA readers described a well-known drawback of CTA, that is its tendency to smooth vessels adjacent to the neck into the wall of the aneurysm (Fig 4).

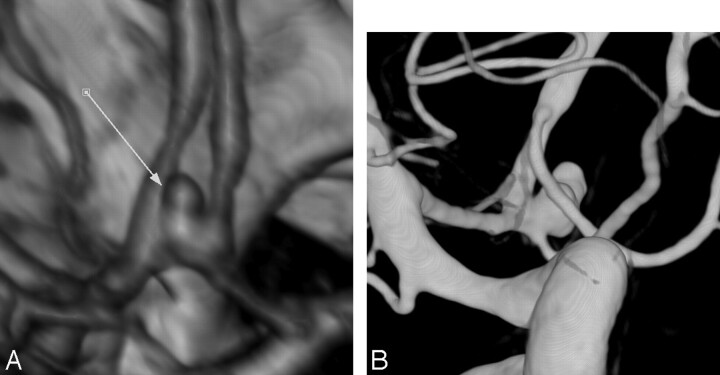

Fig 4.

Images obtained in a 44-year-old woman with SAH. A, 3D volume-rendered CTA image in oblique view shows a small anterior communicating aneurysm. Adjacent A2 segment from both anterior cerebral arteries “seem” to be incorporated within the aneurysm wall (arrow). B, Oblique view from pre-embolization DSA shows that both A2 segments are clearly separated from the aneurysm neck and sac.

CTA to Triage Patients between Clipping and Coiling

Current therapeutic options for ruptured intracranial aneurysms include EVT and surgical clipping. To choose the appropriate treatment, different factors related to the patient but also to the aneurysm must precisely be known. Concerning the aneurysm, needed information concern morphologic characteristics, including the sac maximal diameter, the neck width, and the presence of a branch arising from the sac. If DSA is to be replaced by CTA to choose the appropriate treatment, CTA must provide precise information concerning the aneurysm morphologic features. However, only a few studies have evaluated whether CTA may replace DSA in the process of choosing the most appropriate treatment for ruptured intracranial aneurysms.11–14 These authors showed that CTA may be used as the sole examination to triage patients for EVT or clipping in most cases. Hoh et al14 showed that a prospective CTA-only protocol was effective in permitting treatment in 86% of patients with SAH. In the most recent study by Agid et al,13 CTA could select between treatment options in 95.7% of patients with aneurysm. This difference may be explained by the fact that Hoh et al14 used a 4-detector-row scanner, whereas Agid et al13 used a 64-detector-row scanner. These findings were confirmed in this study, because our neurovascular team could rely on CTA images alone to choose the appropriate treatment in all of the patients treated for a ruptured aneurysm. In this study, we also regarded successful coiling as proof that a correct treatment decision was made.13 Successful EVT was achieved in 94.9% of the selected patients. Based on these results, we may, thus, conclude that CTA is very useful in the decision process regarding whether to coil or to clip an aneurysm. However, in 2 patients, EVT could not be performed because of insufficient information concerning the evaluation of the parent artery at the cervical level. One patient had a significant ICA stenosis and the other one had an extracranial PICA with multiple loops. These anatomic features prevented a safe catheterization of the aneurysm, and the patients were referred for surgical clipping. Therefore, we will change our CTA acquisition protocol to evaluate the parent artery at the cervical level. Indeed, with a 64-row multisection CT scanner, scrutiny of the larger proximal arteries (cervical segment) to evaluate suitability for endovascular access is possible at the same time as visualization of intracranial aneurysms because these scanners offer the ability to acquire images from the aortic arch to the vertex in a single acquisition.

Interobserver Agreements

Previously published series, concerning the use of single-23 or 4-row-multisection CTA,17 have evaluated interobserver agreements for aneurysm detection and morphologic evaluation. For aneurysms detection, Dammert et al17 and White et al23 reported mean κ values of 0.601 and 0.73, respectively. For aneurysm size and neck evaluations, Dammert et al17 reported mean κ values of 0.747 and 0.648, respectively. Although our study included more CTA readers, the mean interobserver agreements for aneurysm detection (κ = 0.732), aneurysm maximal diameter (κ = 0.876), and neck measurement (κ = 0.779) were slightly better than those reported in these studies.17,23 This difference is probably related to the use of a 64-row multisection CT scanner in our study. These improvements in technology have decreased acquisition time, improved spatial resolution, and increased the accuracy of CTA to detect and evaluate intracranial aneurysms.

Conclusion

CTA with a 64-section scanner is an accurate tool with a good interobserver and intertechnique reproducibility for the detection and the evaluation of ruptured intracranial aneurysms. It allows for precise depiction of aneurysm morphology that is mandatory to promptly choose the appropriate treatment. Moreover, CTA may determine the bleeding etiology in patients with SAH in most cases. Therefore, a strategy of using CTA as the primary imaging method for SAH appears to be effective, and DSA should be reserved for cases of uncertainty.

References

- 1.Linn FH, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, et al. Incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage: role of region year and rate of CT scanning: a meta-analysis. Stroke 1996;27:625–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayberg MR, Batjer HH, Dacey, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1994;25:2315–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloft HJ, Joseph GJ, Dion JE. Risk of cerebral angiography in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral aneurysms, and arteriovenous malformations: a meta-analysis. Stroke 1999;30:317–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz RB, Tice HM, Hooten SM, et al. Evaluation of cerebral aneurysms with helical CT: correlation with conventional angiography and MR angiography. Radiology 1994;192:717–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang EY, Chan M, Hsiang JH, et al. Detection and assessment of intracranial aneurysms: value of CT angiography with shaded-surface display. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995;165:1497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White PM, Wardlaw JM, Easton V. Can non-invasive imaging accurately depict intracranial aneurysms? A systematic review. Radiology 2000;217:361–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karamessini MT, Kagadis GC, Petsas T, et al. CT angiography with three-dimensional techniques for the early diagnosis of intracranial aneurysms: comparison with intra-arterial DSA and the surgical findings. Eur J Radiol 2004;49:212–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teksam M, McKinney A, Casey S, et al. Multi-section CT angiography for detection of cerebral aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1485–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wintermark M, Uske A, Chalaron M, et al. Multislice computerized tomography angiography in the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms: a comparison with intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography. J Neurosurg 2003;98:828–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayaraman MV, Mayo-Smith WW, Tung GA, et al. Detection of intracranial aneurysms: multi-detector row CT angiography compared with DSA. Radiology 2004;230:510–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tipper G, U-King-Im JM, Price SJ, et al. Detection and evaluation of intracranial aneurysms with 16-row multislice CT angiography. Clin Radiol 2005;60:565–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villablanca JP, Hooshi P, Martin N, et al. Three-dimensional helical computerized tomography angiography in the diagnosis, characterization, and management of middle cerebral artery aneurysms: comparison with conventional angiography and intra-operative findings. J Neurosurg 2002;97:1322–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agid R, Lee SK, Willinsky R, et al. Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage: using 64-slice multidetector CT angiography to “triage” patients’ treatment. Neuroradiology 2006;48:787–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoh BL, Cheung AC, Rabinov JD, et al. Results of a prospective protocol of computed tomographic angiography in place of catheter angiography as the only diagnostic and pretreatment planning study for cerebral aneurysms by a combined neurovascular team. Neurosurgery 2004;54:1329–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedashti AR, Rufenacht DA, Delavelle J, et al. Therapeutic decision and management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage based on computed tomographic angiography. Br J Neurosurg 2003;17:46–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon DY, Lim KJ, Choi CS, et al. Detection and characterization of intracranial aneurysms with 16-channel multidetector row CT angiography: a prospective comparison of volume-rendered images and digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007;28:60–67 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dammert S, Krings T, Moller-Hartmann W, et al. Detection of intracranial aneurysms with multislice CT: comparison with conventional angiography. Neuroradiology 2004;46:427–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kouskouras C, Charitanti A, Giavroglou C, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: evaluation using CTA and MRA. Correlation with DSA and intraoperative findings. Neuroradiology 2004;46:842–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt W, Hess R. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1968;28:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kershenovich A, Rappaport ZH, Maimon S. Brain computed tomography angiographic scans as the sole diagnostic examination for excluding aneurysms in patients with perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2006;59:798–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto S, Kiura Y, Shibukawa M, et al. Subtracted 3D CT angiography for evaluation of internal carotid artery aneurysms: comparison with conventional digital subtraction angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:1332–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomandl BF, Hammen T, Klotz E, et al. Bone-subtraction CT angiography for the evaluation of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:55–59 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White PM, Teasdale EM, Wardlaw JM, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: CT angiography and MR angiography for detection–prospective blinded comparison in a large patient cohort. Radiology 2001;219:739–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]