Abstract

Purpose

Treatment of typical atrial flutter (AFL) with cavo-tricuspid isthmus (CTI) ablation is associated with a high occurrence rate of new onset atrial fibrillation (AF) during follow-up. There are data to support the addition of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) to CTI ablation in patients with both AF and AFL, but the role of cryoballoon PVI only, with no CTI ablation, in AFL patients with no prior documentation of AF has not been studied.

Methods

CRAFT is an international, prospective, randomised, open with blinded assessment, multicentre superiority study comparing radiofrequency CTI ablation and cryoballoon PVI in patients with typical AFL. Participants with typical AFL are randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either treatment arm, with patients randomised to PVI not receiving CTI ablation. Post-procedural cardiac monitoring is performed using an implantable loop recorder. The primary endpoint is time to first recurrence of sustained symptomatic atrial arrhythmia. Key secondary endpoints include (1) total arrhythmia burden at 12 months, (2) time to first episode of AF lasting ≥ 2 min, (3) time to recurrence of AFL or AT and (4) procedural and fluoroscopy times. The primary safety endpoint is the composite of death, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, cardiac tamponade requiring drainage, atrio-oesophageal fistula, requirement for a permanent pacemaker, serious vascular complications requiring intervention or delaying discharge and persistent phrenic nerve palsy lasting > 24 h.

Conclusion

This study compares the outcomes of 2 different approaches to typical AFL—the conventional ‘substrate’-based strategy of radiofrequency CTI ablation versus a novel ‘trigger’-based strategy of cryoballoon PVI.

Trial registration

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10840-020-00746-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Atrial flutter, Cavo-tricuspid isthmus, Cryoballoon, Radiofrequency, Ablation, Atrial fibrillation

Background

Typical atrial flutter (AFL) is a macro-reentrant tachycardia with a circuit within the right atrium involving the cavo-tricuspid isthmus (CTI) as the critical isthmus. In patients with AFL, the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs (AADs) to maintain sinus rhythm has limited success [1]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of the CTI has a very high acute success rate and is often used as first line treatment. However, as many as half of these patients go on to develop atrial fibrillation (AF) during follow-up [2, 3]. The elevated risk of AF among patients with AFL indicates the presence of shared underlying disease processes that remain unchanged with only CTI ablation. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that pulmonary vein (PV) ectopy is a common initiating trigger for both arrhythmias [4, 5].

Previous studies have demonstrated the benefit of a combined pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and CTI ablation approach among patients with AFL [6–8]. A small single centre study even showed the efficacy of standalone PVI in patients with typical AFL compared with AADs or CTI ablation [1]. Despite this, CTI ablation has remained the preferred option for patients with typical AFL, partly because of the perceived complexity of traditional PVI with RFA, and the high possibility of requiring multiple procedures to achieve durable PVI [1]. As such, in spite of the recognition that CTI ablation often represents only a short-term or partial solution, it continues to be the recommended, first-line treatment approach for symptomatic, recurrent, typical AFL [9, 10].

In recent years, cryoballoon ablation has been developed for AF [11] and has been shown to be non-inferior to RFA in terms of efficacy and safety profile [12]. Cryoballoon ablation is also associated with a shorter learning curve, with more reproducible results across operators and shorter procedure times than RFA, while ensuring a high probability of creating durable PVI [13]. However, the use of cryoballoon PVI only in patients with typical AFL and no prior documentation of AF has not been studied.

Methods

Primary endpoint and hypothesis

The primary hypothesis of the CRAFT study is that cryoballoon PVI is superior to CTI ablation as first-line treatment for typical AFL in terms of recurrence of all atrial arrhythmias; it offers the prospect of more complete arrhythmia elimination with a single procedure, while resulting in no increase in procedural risk, or in-catheter laboratory resource utilisation. The primary endpoint is defined as time to first recurrence of sustained (> 30 s) symptomatic atrial arrhythmia, including AF, AFL and atrial tachycardia (AT), following a blanking period of 4 weeks as assessed by implantable loop recorder (ILR) data.

Secondary endpoints

Key secondary endpoints include (1) time to first episode of AF lasting ≥ 2 min, (2) total AF burden at 12 months, (3) time to recurrence of AFL or AT, (4) procedural and fluoroscopy times and radiation dose and (5) quality of life (QoL) changes at 12 months compared with baseline.

Safety analysis

The primary safety endpoint is the composite of death, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, cardiac tamponade requiring drainage, atrio-oesophageal fistula, requirement for a permanent pacemaker, serious vascular complications requiring intervention or delaying discharge and persistent phrenic nerve palsy lasting > 24 h. A list of possible procedure-related adverse events is shown in Table 1. A definition of terms is provided in Supplemental Material.

Table 1.

Procedure-related adverse events

| Air embolism | |

| Atrio-oesophageal perforation or fistula | |

| Atrio-septal defect | |

| Atrioventricular node damage | |

| Bleedings events, including groin haematoma | |

| Cardiac or coronary artery perforation | |

| Death | |

| Dysphagia | |

| Major vascular complication | |

| Myocardial infarction | |

| Need for unplanned cardiac or vascular surgery | |

| Pericardial effusion | |

| Pericarditis | |

| Persistent or sustained cardiac arrhythmia | |

| Phrenic nerve paralysis | |

| Pulmonary vein stenosis | |

| Site infection from loop recorder insertion | |

| Stroke or transient ischaemic attack |

Study design

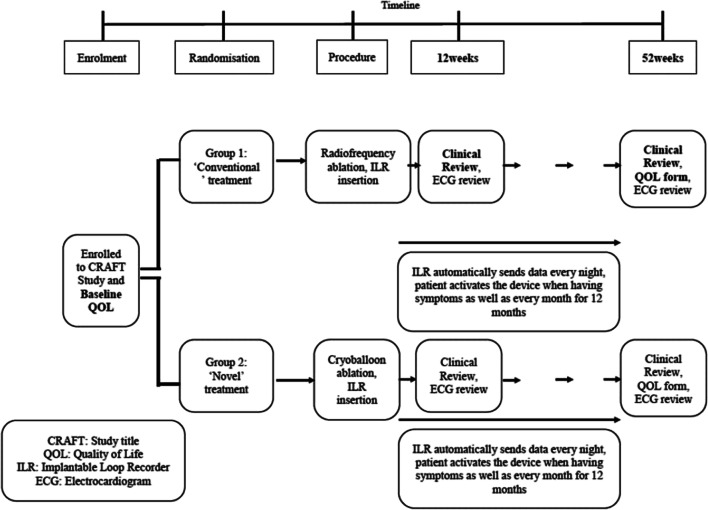

CRAFT study is an international, prospective, randomized, open with blinded assessment, multicentre superiority study being performed at 12 sites in the UK and Switzerland. The study is funded by Medtronic Saarl Ltd., but the investigators are solely responsible for the study design and conduct, data collection and analyses, manuscript writing and decision to publish. The study has been approved by the ethical review committees at each site. The trial is being conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Block randomisation is used to allocate participants in a 1:1 ratio to either:

‘Conventional’ treatment with radiofrequency CTI ablation, OR

‘Novel’ treatment with cryoballoon PVI

A study flowchart is included for illustration in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart for CRAFT

Participants

The study population consists of patients with persistent AFL in whom the flutter morphology on standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is felt to be compatible with typical, CTI-dependent-AFL. Any documentation of previous AF automatically excludes the patient from the study. At minimum, patients were required to have an ambulatory cardiac monitoring or ECGs recorded on at least 3 different dates to exclude AF. Other key exclusion criteria include flutter diagnosed solely on ambulatory Holter, suspected left atrial AFL, prior CTI ablation or PVI, severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction < 30%) and morbid obesity (body mass index ≥ 40). A full list of exclusion criteria is provided in the Supplemental Material. A signed, informed consent form is obtained from every participant prior to randomisation.

Interventions

Ultrasound-guided vascular access and fluoroscopy guidance are recommended for all cases. For participants presenting to the catheter laboratory in AFL, entrainment is performed from the proximal and distal poles of a catheter situated within the coronary sinus, and CTI to confirm the diagnosis of CTI-dependent AFL. Participants found to have non-CTI-dependent AFL or AF at the time of the procedure will be excluded from undergoing the allocated intervention they have been randomised to. Instead, the investigators will be free to offer them ablation treatment appropriate to their arrhythmia.

Radiofrequency CTI ablation

In the control arm, the choice of ablation catheter, settings and overall strategy is at the discretion of individual operators. Using fluoroscopy only, the aim is to achieve bidirectional conduction block across the CTI that persists for at least 15 min following the last radiofrequency application, as has previously been described [14, 15].

Cryoballoon PVI

A single trans-septal puncture is performed. Routine administration of heparin is used with a target activated clotting time of > 250. The Arctic Front Advance cryoballoon (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA) and Achieve Advance Mapping catheter (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA) are employed for all cases. The aim is to achieve a single 180-s ‘effective’ freeze for each pulmonary vein. A freeze is considered ‘effective’ if either of these criteria is met:

Time to PVI < 60 s if PV signals are discernible on any pole(s) of the Achieve Advance Mapping catheter, OR

If PV signals not discernible on any pole(s) of the Achieve Advance Mapping catheter, lowering of balloon temperature below − 40 °C at 60 s

In the event that an effective freeze is not achieved at 60 s, the freeze is terminated, and further ablation attempts are made with a better contrast seal. No ‘bonus’ freeze is routinely applied for any PV once an effective freeze has been delivered. In the case of 2 unsuccessful attempts to achieve an effective freeze for any PV, a 240-s freeze is delivered to the vein, followed by an additional 180-s freeze if PVI is not achieved by the former. Failure to achieve PVI with this maximum of 4 freezes is not pursued with further ablation attempts. Targeted treatment of non-PV triggers or use of focal RF catheter as an adjunct is not allowed by the protocol.

Prior to removal of the left atrial catheters, an assessment of each PV is undertaken with the Achieve Advance Mapping catheter. If spontaneous PV reconnection is identified, cryoballoon application is repeated, where required. Participants in persistent AFL will be cardioverted at the end of the procedure. Protamine administration is allowed prior to sheath removal.

Implantable loop recorder

The Reveal LINQ (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA) is implanted according to the manufacturer’s instructions during the ablation procedure. The programmed algorithm for arrhythmia detection is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Algorithm for programming LINQ devices

| Parameter | Settings |

|---|---|

| Reason for monitoring | Suspected AF |

| Detection | |

| Tachy | On |

| Interval rate | 146 bpm |

| Duration | 12 beats |

| Brady | On |

| Interval rate | 30 bpm |

| Duration | 4 beats |

| Pauses | On |

| Duration | 3 s |

| AT/AF detection | AF only |

| Sensitivity | Less sensitive (nominal) |

| Ectopy rejection | Nominal |

| AT/AF recording threshold | All episodes |

AF atrial fibrillation, AT atrial tachycardia, bpm beats per minute

Follow-up

The study ‘blanking period’ is defined as the initial 4 weeks following ablation. All AADs are discontinued after this period. Cross-overs are not permitted in the blanking period, with the exception of recurrent AFL with 1:1 atrio-ventricular conduction that is resistant to rate control measures. The use of oral anticoagulation is mandated for a minimum of 2 months and subsequently according to individual stroke risk as assessed by the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Participants are provided with a symptom diary and asked to transmit monthly ECG recordings from their loop recorder. In addition, participants are instructed to record and transmit ECG recordings following arrhythmia-related symptoms. Transmitted data are reviewed regularly by cardiac physiologists who are blinded to the randomisation status. The follow-up duration is 12 months, with planned study visits at 3 and 12 months, when quality of life assessments are performed with the validated EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. Recurrent atrial arrhythmias are treated at the discretion of the responsible clinician. Clinical events will be adjudicated by a panel of cardiologists, who will be blinded to treatment allocation.

Sample size calculation

In the PReVENT AF study, incidence of AF following CTI ablation for typical AFL was reported in 52% of participants at 12 months follow-up using an ILR [7]. In a meta-analysis by Maskoun et al., the incidence of AF in a similar patient cohort was 45% over a follow-up period of 16 months [16]. However, this included studies with any form of ambulatory ECG monitoring lasting > 7 days. Based on these data, a 50% incidence of atrial arrhythmias following CTI ablation for typical AFL at 12 months is assumed. We anticipate that cryoballoon PVI will reduce the risk of atrial arrhythmias to 25%. Therefore, with an alpha value of 0.05 and power of 80%, the number of participants required to detect a significant difference for a two-sided test is estimated at 58 per group. To cope with a potential loss to follow-up of 11%, a minimum of 130 subjects will be enrolled in the study.

Funding and sponsorship

CRAFT is funded by Medtronic International Trading Sarl as part of an Investigator Sponsored Study programme (Grant AF-3908) and is sponsored by Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (UK sites) and University Hospital Basel (Swiss sites).

Discussion

The CRAFT study is the first randomised controlled trial that compares cryoballoon PVI to radiofrequency CTI ablation for typical AFL. At present, the mode of treatment for symptomatic, recurrent, typical AFL by radiofrequency CTI ablation fails to address the PVs as potential initiating triggers of atrial arrhythmias [4, 5, 17, 18]. Despite evidence to demonstrate better clinical outcomes in terms of arrhythmia-free survival among such patients treated with additional PVI (Table 3), there has been limited uptake with this approach.

Table 3.

Randomised controlled trials on the role of PVI in isolated AFL

| Study | n | Ablation strategy | Cardiac monitoring | Follow-up period | Incidence of atrial arrhythmias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Navarette [6] | 48 | CTI vs CTI + PVI | 48-h Holter | 16 months | 56% vs 13% |

| PReVENT AF [7] | 50 | CTI vs CTI + PVI | ILR | 12 months | 52% vs 12% |

| REDUCE AF [8] | 216 | CTI vs CTI + PVI | ILR, event recorder or 7-day Holter | 18 months | 40% vs 29% |

| Triple A* [1] | 43 | CTI vs PVI | ILR | 17 months | 61% vs 10% |

AF atrial fibrillation, AFL atrial flutter, CTI cavo-tricuspid isthmus, ILR implantable loop recorder, PVI pulmonary vein isolation

*Subset of whole study cohort

Navarrete et al. found that combined CTI ablation and pulmonary vein isolation in patients with typical AFL was associated with a significant improvement in freedom from atrial arrhythmias over a follow-up duration of 16 months compared with CTI ablation alone (56% vs 13%) [6]. Similar findings were reported in PReVENT AF Study I, which was a prospective, single-blind, randomised controlled trial [7]. However, in REDUCE AF, the addition of PVI in patients who underwent CTI ablation for typical AFL only resulted in a significantly lower rate of AF or atrial tachycardia recurrence among those aged > 55 years [8].

The Triple A study has previously demonstrated superiority of standalone PVI over CTI ablation in patients with isolated AFL [1]. However, the limitations of this study include the single-centre study design, small sample size and need for repeat ablation procedures in more than a third of patients in the PVI arm to achieve durable PVI, likely because of the use of RF catheters without contact force measurement capability. However, with the rapidly expanding field of cryoballoon PVI which allows more efficient and durable lesion formation in the PVs, there is a need to evaluate the use of this technology in typical AFL.

Conclusion

The CRAFT study is an international, multicentre, randomised study comparing clinical outcomes with 2 different approaches to typical AFL—cryoballoon PVI versus radiofrequency CTI ablation. It will increase our understanding of the role of PV triggers in AFL and provide data on whether cryoballoon PVI could be used as an alternative to radiofrequency CTI ablation as a first-line treatment for typical AFL.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 25 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Prof Rodney Stables, Chair, British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Collaborative, for his invaluable help in designing the trial and providing research governance oversight.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

WYD, EW, LT, MT, GH, CM, KR, MB, IPT, ZC, RB, CR, NC and SM have no relevant disclosures to declare. MD has received fellowship funding from Biosense and speaker fees from Boston-Scientific. For work outside the submitted study, TR has received research grants from the Goldschmidt-Jacobson Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Swiss Heart Foundation, the European Union (Eurostars 9799–ALVALE), the Professor Max Cloëtta Foundation, the Cardiovascular Research Foundation Basel, the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel; speaker/consulting honoraria or travel support from Abbott/SJM, Astra Zeneca, Brahms, Bayer, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston-Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Pfizer-BMS and Roche; and support for his institution’s fellowship programme from Abbott/SJM, Biosense-Webster, Biotronik, Boston-Scientific and Medtronic. CS reports grants and lecture fees from Biosense Webster and Medtronic and served as a proctor for Biosense Webster and Medtronic. DG is a speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific; proctor for Abbott and has received research grants from Medtronic, Biosense Webster and Boston Scientific.

Footnotes

Wern Yew Ding and Emmanuel Williams joint first authors

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schneider R, Lauschke J, Tischer T, Schneider C, Voss W, Moehlenkamp F, et al. Pulmonary vein triggers play an important role in the initiation of atrial flutter: initial results from the prospective randomized atrial fibrillation ablation in atrial flutter (triple a) trial. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:865–71. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Chinitz JS, Gerstenfeld EP, Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation is common after ablation of isolated atrial flutter during long-term follow-up. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(8):1029–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celikyurt U, Knecht S, Kuehne M, Reichlin T, Muehl A, Spies F, et al. Incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cavotricuspid isthmus ablation for atrial flutter. Europace. 2017;19(11):1776–80. 10.1093/europace/euw343. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Waldo AL, Feld GK. Inter-relationships of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter mechanisms and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(8):779–86. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Waldo AL. Mechanisms of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation: distinct entities or two sides of a coin? Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54(2):217–229. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarrete A, Conte F, Moran M, Ali I, Milikan N. Ablation of atrial fibrillation at the time of cavotricuspid isthmus ablation in patients with atrial flutter without documented atrial fibrillation derives a better long-term benefit. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22(1):34–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinberg JS, Romanov A, Musat D, Preminger M, Bayramova S, Artyomenko S, et al. Prophylactic pulmonary vein isolation during isthmus ablation for atrial flutter: the PReVENT AF study I. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(9):1567–72. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mohanty, S., Natale, A., Mohanty, P., DI Biase, L., Trivedi, C., Santangeli, P., … Dixit, S. (2015). Pulmonary vein isolation to reduce future risk of atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing typical flutter ablation: results from a randomized pilot study (REDUCE AF). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol, 26(8), 819–825. doi:10.1111/jce.12688. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Camm AJ, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(15):1493–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, Arribas F, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The task force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2019;41(5):655–720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, Irwin JM, Champagne J, Guerra PG, et al. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first results of the North American Arctic Front (STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(16):1713–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuck K-H, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KRJ, et al. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2235–45. 10.1056/NEJMoa1602014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Reddy VY, Sediva L, Petru J, Skoda J, Chovanec M, Chitovova Z, et al. Durability of pulmonary vein isolation with cryoballoon ablation: results from the sustained pv isolation with Arctic Front Advance (SUPIR) study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:493–500. doi: 10.1111/jce.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah DC, Takahashi A, Jais P, Hocini M, Clementy J, Haissaguerre M. Local electrogram-based criteria of cavotricuspid isthmus block. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10(5):662–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallès E, Cabrera S, Benito B, Alcalde O, Jiménez J, Martí-Almor J. Burning the gap: electrical and anatomical basis of the incremental pacing maneuver for cavotricuspid isthmus block assessment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27(6):694–698. doi: 10.1111/jce.12965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maskoun W, Pino MI, Ayoub K, Llanos OL, Almomani A, Nairooz R, Hakeem A, Miller J. Incidence of atrial fibrillation after atrial flutter ablation. JACC Clinical electrophysiology. 2016;2(6):682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):659–66. 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Chen SA, Hsieh MH, Tai CT, Tsai CF, Prakash VS, Yu WC, et al. Initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins: electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological responses, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1999;100(18):1879–86. 10.1161/01.cir.100.18.1879. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 25 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.