Abstract

Entomopathogenic fungi show great promise as pesticides in terms of their relatively high target specificity, low non-target toxicity, and low residual effects in agricultural fields and the environment. However, they also frequently have characteristics that limit their use, especially concerning tolerances to temperature, ultraviolet radiation, or other abiotic factors. The devastating ectoparasite of honey bees, Varroa destructor, is susceptible to entomopathogenic fungi, but the relatively warm temperatures inside honey bee hives have prevented these fungi from becoming effective control measures. Using a combination of traditional selection and directed evolution techniques developed for this system, new strains of Metarhizium brunneum were created that survived, germinated, and grew better at bee hive temperatures (35 °C). Field tests with full-sized honey bee colonies confirmed that the new strain JH1078 is more virulent against Varroa mites and controls the pest comparable to current treatments. These results indicate that entomopathogenic fungi are evolutionarily labile and capable of playing a larger role in modern pest management practices.

Subject terms: Evolution, Microbiology

Introduction

Biological pesticides based on naturally occurring microbes that infect pest species have been available to growers in the U.S. and global markets for decades, but they have failed to find widespread use1. These microbial biopesticides are considered to have inherently reduced risk by the U.S Environmental Protection Agency due to a suite of favorable toxicological characteristics2. Compared to traditional chemical synthetic pesticides, microbial biopesticides generally have very low toxicity to humans and other vertebrates, fast decomposition leading to reduced residues and environmental pollution, and high species specificity leading to reduced non-target effects2. Additionally, microbial biopesticides are easily integrated into the growing market for certified organic food3, and pests may be slower to evolve resistance to microbial biopesticides than to traditional chemical pesticides4.

Although biopesticides make up an increasing percentage of global pesticide usage, they have generally failed to supplant traditional synthetic chemical pesticides outside of certain niche markets5. One of the primary reasons is that the effectiveness of microbes for pest control is frequently limited by the susceptibility of the microbes to temperature, ultraviolet radiation, pH, or other abiotic factors6–8. This susceptibility to environmental stress shortens the duration of treatment and lowers the overall pest control gained from each application. Increasing the tolerance of microbial biopesticides to abiotic factors is acknowledged as an elusive yet key transformation step if they are to find wider use1,7.

Varroa destructor is an ectoparasite of honey bees widely considered to be the primary driver of declining honey bee health in recent decades. Although a variety of interacting factors including pathogens, pesticides, and nutritional stress have contributed to declining honey bee health9–12, the Varroa mite is the most commonly reported cause of colony loss for commercial beekeepers in the United States13,14 and is considered the single greatest threat to apiculture world-wide15. This, in turn, threatens the ~ $238 billion in crops worldwide that require insect pollination16. Varroa feed on adult and immature honey bees by puncturing the exoskeleton with sharp mouthparts and consuming bee tissues through extra-oral digestion17. Feeding by Varroa weakens bees, reduces worker life-span and foraging capability, and vectors some of the most destructive honey bee viruses including Deformed Wing Virus, Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus, Kashmir Bee Virus, and Sacbrood Virus18,19. If left untreated, Varroa infected colonies have an expected lifespan of 1–3 years15,19. Additionally, Varroa infected bees are more likely to drift to neighboring colonies, introducing Varroa and associated viruses to uninfected colonies20,21. This is especially problematic for bees in commercial pollination settings where thousands of hives from different beekeepers and locations are crowded seasonally into orchards and agricultural fields22,23.

Currently, beekeepers are largely reliant on chemical acaricides to control Varroa despite the dangers that these chemicals pose to bees and the ongoing issues with chemical resistance in the mites. These acaricides have been linked to numerous honey bee health problems, and many studies have shown that residues can accumulate in the hive over time24–26. Unintended effects on honey bees include increased mortality in brood and adults27 and an increased susceptibility to pathogens and agrichemicals28–30. There is a growing body of evidence that links acaricides to reproductive issues in both queens31–33 and drones34,35. Additionally, interactions between different chemical acaricides can increase their toxicity to bees36,37 and breakdown metabolites have been shown to have toxic effects as well38,39. Compounding the situation further are the many other insecticides, fungicides, and other agrichemicals that honey bees encounter while foraging in and around agricultural fields40. Traditional chemical acaricides also present logistical issues to beekeepers including increased personal protection equipment requirements and prohibition of treatment during honey production. Varroa have repeatedly evolved resistance to the chemical acaricides most commonly used by beekeepers, including multiple pyrethroids41, the organophosphate coumaphos42, and the amidine amitraz43.

Several laboratories have demonstrated that Varroa are susceptible to entomopathogenic fungi, including Beauvaria bassiana, Hirsutella thompsonii, and Metarhizium anisopliae44–47. Field tests with Metarhizium showed the fungus was capable of controlling mites47,48, sometimes with results comparable to the commonly used chemical acaricides of the time49,50. However, despite attempts with several different formulations, commercially available entomopathogenic fungi that were tested generally suffered from low consistency in their ability to control Varroa51. Researchers repeatedly noted that the relatively warm temperatures found in honey bee hives, 35 °C52, was detrimental to the survival and infection potential of spores, leading to rapid decreases in treatment efficacy43,53. This situation is compounded by the life cycle of Varroa, which spend much of their life living inside closed brood cells with developing bee pupae. This shelters the mites from treatments with short persistence, allowing mite levels to quickly reestablish51,54.

Although researchers have now screened and tested dozens of existing strains of entomopathogenic fungi for their potential for Varroa control, no one has yet attempted to create a strain specifically for Varroa control through any means of genetic manipulation or repetitive selection. In addition to showing promise as a microbial biopesticide against Varroa, the Metarhizium PARB clade (including the species M. anisopliae and M. brunneum), has shown itself to be modifiable through genetic engineering55 or mutagenesis sectorization screening56. In the following experiments, we subjected a strain of Metarhizium brunneum to repeated cycles of selection using both directed evolution in laboratory incubators and repetitive selection in full-sized honey bee colonies. This resulted in strains that are better able to survive under bee hive conditions and are better able to control Varroa than parental strains.

Results and discussion

Initial trials of Metarhizium for Varroa control used 30 established full-sized honey bee colonies that were divided into three groups, balancing each group for colony population and starting mite levels. The F52 strain of Metarhizium brunneum (ATCC #90448) was chosen for testing because of its reported efficacy against Varroa47–49, its genetic manipulability55, and evidence that the pathogenicity and control potential of current strains can be improved57. In addition, we tested a related strain of Metarhizium brunneum56 that displays delayed spore production to test for behavioral or pest control differences of Metarhizium hyphae as compared to spores. Control colonies received uninoculated agar. The treatment of hives consisted of inverting agar discs from a 95 mm plastic petri dish onto the top bars of the frames of comb in the hive, one disc per box.

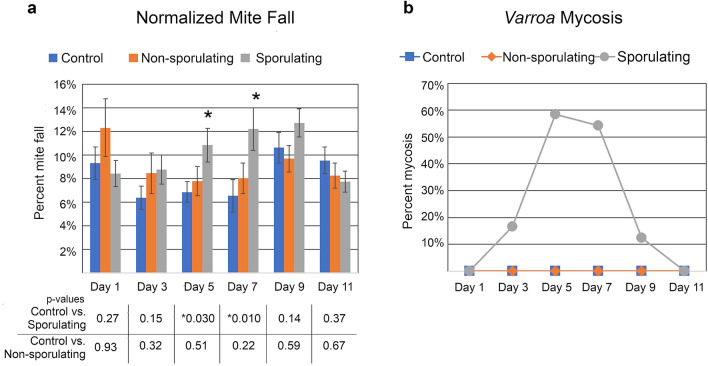

Treatment with M. brunneum F52 that was producing mitospores (asexual spores, sometimes referred to as conidia in Metarhizium) significantly increased the number of dead mites collected off bottom board sticky cards compared to hives that received uninoculated agar plates (Fig. 1a; day 5 and 7 p < 0.03). Varroa control by this sporulating strain, estimated to have delivered 8.76 × 108 mitospores per treatment, peaked between days 5–7 after treatment, corresponding to peak mycosis (Fig. 1b), and then declined back to non-significant levels from day 9 onward. The rapid loss of mitospore viability in this first trial was somewhat expected, as previous researchers have noted the susceptibility of Metarhizium to temperatures found in honey bee hives. Worker bees were observed cleaning living fungus off the agar disk promptly after treatment, suggesting that mitospore production by the treatment declined rapidly as the living fungus was removed. However, this action may have facilitated the spread of mitospores from the dish onto living bees and around the colony.

Figure 1.

The effects of Metarhizium treatment on Varroa mite levels. (a) Mite fall onto sticky cards in hives treated with pre-sporulating or sporulating strains of Metarhizium. Data are normalized to total number of fallen mites for each colony. Number of colonies = 10 (control), 10 (non-sporulating), 10 (sporulating). (b) Percentage of mites killed by Metarhizium. Fallen mites were surface sterilized and plated onto nutrient agar. Varroa growing Metarhizium were considered to have died from mycosis. N = 84 (control), 156 (non-sporulating), 168 (sporulating). T tests were used to determine significance.

Metarhizium that was not producing mitospores did not show any effect of treatment (p > 0.2 for all days) (Fig. 1). Although Metarhizium produces destruxins and other compounds with pesticidal properties, these results confirm previous research51 showing that mitospores are the necessary infectious agent of Metarhizium for Varroa control. Although Metarhizium hyphae can display some mycoattractant effects56, we did not observe any attraction by Varroa to the fungus. Therefore, the primary mode of action for Varroa control is highly likely through mitospore adhesion and germination on the mite exoskeleton, followed by hyphal penetration through the exoskeleton and proliferation throughout internal tissues of the mite.

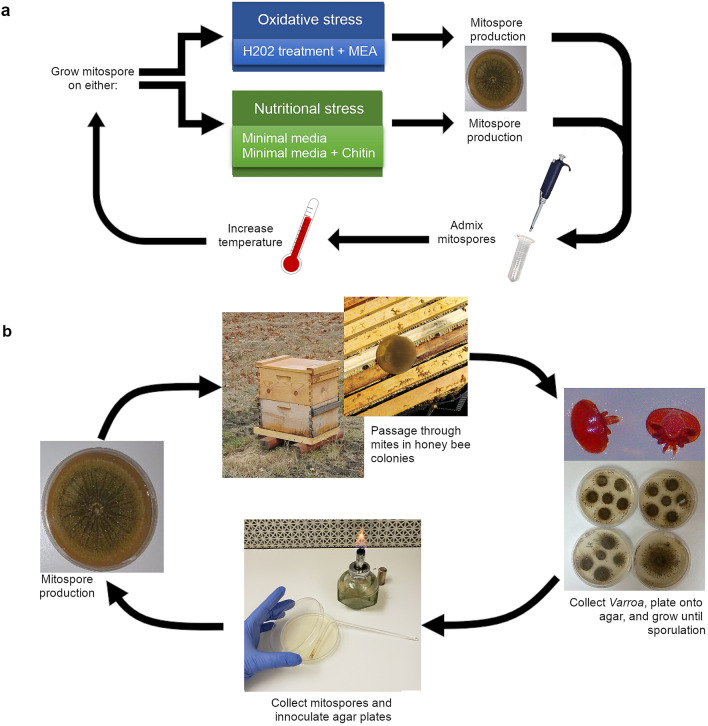

Mites from this initial field trial were collected off sticky cards, surface sterilized, and plated on agar. Metarhizium that grew out of infected mites were subcultured and used as the starting population for a directed evolution process we designed to induce thermotolerance. The fungus was subjected to repetitive cycles of growth and reproduction under stressful conditions at increasing temperatures (Fig. 2a). The stressful conditions were either oxidative stress and mild mutagenicity induced by hydrogen peroxide treatments or nutritional stress induced by growth on minimal media agar amended with or without chitin. Spores exposed to nutritional stress are better able to withstand UV-stress and heat stress and exhibit increased infectivity7,58. There is, however, a tradeoff for fungi grown in nutritionally deficient media; hyphal development is slowed, and mitospore production is decreased59. With each repeated cycle the mitospore population was admixed, and the incubator temperature was gradually increased from the ideal growth temperatures for the starting F52 strain (27 °C) to the temperature found in honey bee hives (35 °C).

Figure 2.

Visual representation of the Metarhizium strain creation process. (a) In vitro workflow for increasing thermotolerance with directed evolution in Metarhizium. (b) Workflow procedure for field selection after directed evolution in the laboratory. Mitospores from mycosed Varroa cadavers are used to create the next generation of treatment.

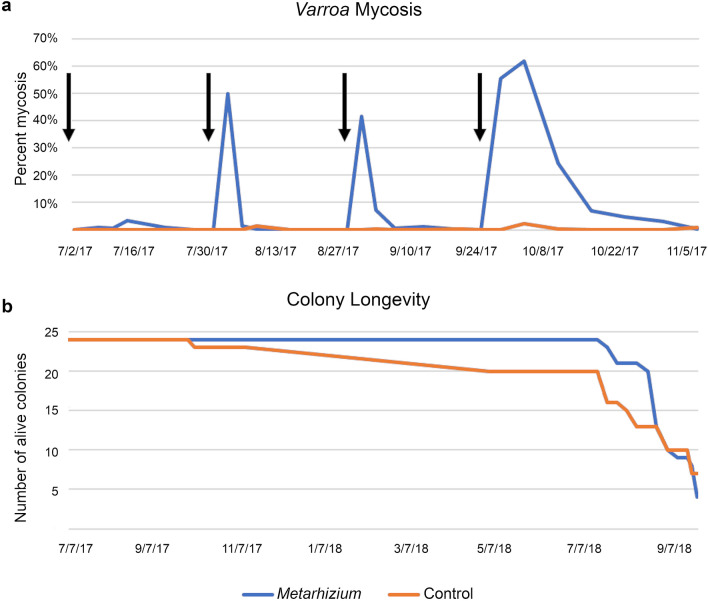

The last generation of spores resulting from the directed evolution process was then used as the starting population for repetitive rounds of field selection. The mitospores were germinated on malt extract agar (MEA) plates, allowed to grow and to produce another generation of mitospores, and then the agar disc was inverted onto the top bars of the frames of comb in full-sized outdoor honey bee colonies (Fig. 2b). A new apiary, designated as the stationary apiary, was established using full-sized colonies started from “two-pound packages” (0.91 kg of bees taken from a common population), with a total of 48 colonies being allocated for repeated treatment with either Metarhizium or uninoculated agar discs as controls. The first round of treatment after the directed evolution procedure did not result in high levels of infection in the mites; we were able to reculture living Metarhizium from 3.38% of mites collected off of sticky cards (Fig. 3a), indicating that a low number of mites were killed by the fungus. This low number was not unexpected, as many of the genetic changes acquired during the directed evolution process would not be favorable for virulence in living hosts under field conditions. Additionally, repeated subculturing on artificial media is known to decrease virulence in as little as 20 subcultures60. Living fungus that was recultured from the infected mites was then grown to sporulation, and the subsequent generation was used to treat the same population of hives again (Fig. 3a). After a single generation of selection through Varroa hosts, this treatment resulted in 49.9% of mites dying from mycosis. The process of harvesting mitospores from dead mites, growing another generation, and treating the colony again was repeated two additional times that field season. The final treatment exhibited extended efficacy, lasting up to 5 weeks post treatment (Fig. 3a), indicating increased tolerance to bee hive conditions. No negative effects were detected and the colonies in the treatment and control groups went into winter with similar bee population estimates (t test p = 0.72 see Supplementary Fig. S1 online).

Figure 3.

Effects of Metarhizium treatment on honey bee colonies. (a) Percentage of Varroa mites dying from Metarhizium mycosis. Black arrows indicate the treatment dates. Following each treatment, Metarhizium was recultured from dead mites and used to create the next generation of treatment. Colony N = 24, 24 (treatment, control). (b) Longevity of hives in the Stationary Apiary. Metarhizium treated hives exhibited longer life span compared to controls (p = 0.022). All hives after August 2018 experienced extreme predation from yellow jackets and eventually perished.

The colonies in the stationary apiary continued to receive treatment of either Metarhizium or uninoculated agar the subsequent year, using the same protocol as before. Hives treated with Metarhizium survived significantly longer than untreated hives (Fig. 3b; p < 0.02), although 42 of the 48 hives succumbed to Varroa, pathogen pressure, and intense yellow jacket predation by the end of year two. Metarhizium treatment delayed the exponential increase in Varroa levels but did not total prevent it (see Supplementary Fig. S2 online). The presence of untreated colonies in the apiary created what are known colloquially as “mite bombs”61. Colonies with high Varroa infestation levels continuously inoculate colonies in the area with mites and associated viruses through drifting bees and honey robbing, leading to health problems for all colonies in the apiary. The spreading of mites from untreated colonies to all colonies can be seen in measurements of mite levels from the stationary apiary (see Supplementary Fig. S3 online).

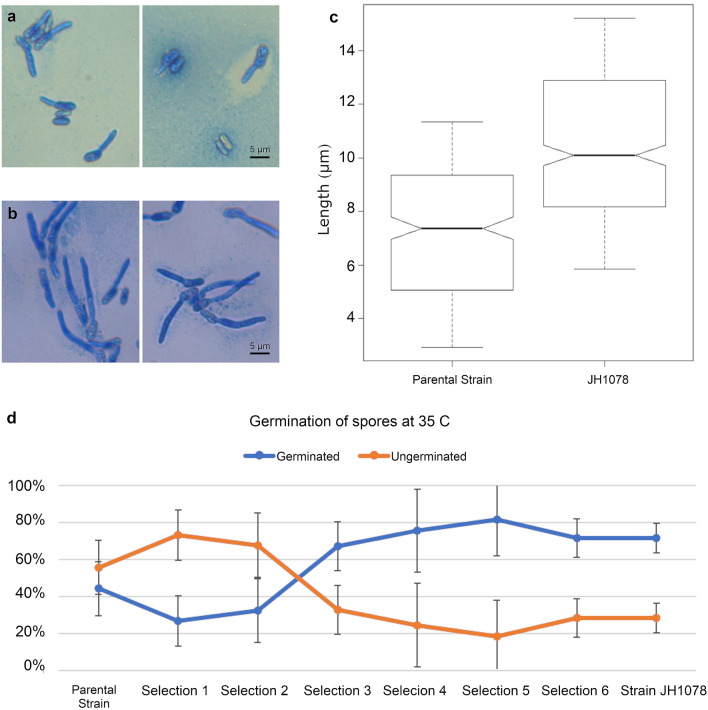

A strain resulting from the selection process at the end of the stationary apiary experiments, designated as strain JH1078, was compared against the parental strain for growth and germination characteristics at 35 °C in a laboratory incubator. There are several significant differences in morphology and longevity between the parental strain F52 and strain JH1078 (Fig. 4a,b). After 24 h incubation at 35 °C, only 44% of the parental strain mitospores were able to germinate, whereas over 70% of strain JH1078 mitospores germinated at 35 °C (Fig. 4d). Of the germinated spores, the parental strain germination tube was on average 4.8 ± 0.20 µm long. Strain JH1078 germination tube was significantly longer (t test p = 8.5 × 10–27), on average 10.48 ± 0.17 µm (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Parental and new strains of Metarhizium have distinct phenotypes at 35 °C. (a,b) Typical germinated mitospores stained with lactophenol cotton blue 24 h after plating and incubation. (a) Parental strain, F52; (b) strain JH1078; (c) average length of germination tube after 24 h of incubation (t test p = 8.5 × 10–27). (d) Germination success rate of mitospores at 35 °C.

To test Metarhizium JH1078 in the context of modern beekeeping operations, full-sized hives that had participated in migratory commercial pollination from February to June were treated with Metarhizium or a common EPA approved Varroa control treatment, a 2.8% oxalic acid drip treatment62. For these experiments, the JH1078 strain was grown on brown rice and placed into natural fiber mesh bags. Each hive was treated with 120 g of colonized grain bearing 2.63 × 108 spores per gram. Both the Metarhizium and oxalic acid treatments were applied twice, 7 days apart. Colonies were sampled for Varroa levels using ethanol washes before the treatments and at the end of the experiment 18 days later. In this field relevant situation, Metarhizium treated colonies did not differ significantly from the oxalic acid treating colonies and trended towards controlling mites better (Kruskall–Wallis p = 0.33; See Supplementary Fig. S4 online).

Conclusions

These results reveal the plasticity of Metarhizium as a biocontrol agent and demonstrate that novel beneficial phenotypes can be created and selected for with a combination of directed evolution in the laboratory and field selection. Importantly, in an era of declining honey bee health, the strains of Metarhizium created in these experiments were able to control Varroa mites and may provide beekeepers with an alternative to chemical acaricides. Additionally, it is possible that the methods presented here could be applied to fungi or other biocontrol agents targeting other arthropod pests. Susceptibility to environmental stressors like heat is frequently noted as a factor limiting the efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi, but these results indicate that such barriers can be overcome.

Materials and methods

Fungal isolates

The starting strain of Metarhizium brunneum that acted as the parental strain before selection was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC #90448). The pre-sporulating strain isolate (US Patent #8501207B2) was obtained from Fungi Perfecti LLC. (Olympia, Washington, USA). The strains were stored in the dark on Malt Extract Agar (MEA) at 4 °C. With the exception of growth during the directed evolution experiments using incubators, Metarhizium for hive treatment was grown on 95 mm MEA Petri plates at room temperature (25 °C) until the plate was fully colonized and producing mitospores, usually after 12–16 days.

Initial field trials of starting strains

In August of 2016, fully established honey bee colonies from four different apiaries in Eastern Washington were evaluated for Varroa mite levels, amount of brood, and total hive population. Thirty colonies were selected for the experiment and assigned to one of three groups, balancing the groups for these health-related traits. The hives were then moved to a new apiary in Troy, Idaho and installed with raised bottom boards that could accommodate sticky cards. In September, the colonies were treated with either sporulating Metarhizium, pre-sporulating Metarhizium, or uninoculated MEA substrate. At the end of the trial, hives were treated with a single strip per brood box of CheckMite+ (Bayer Animal Health, USA; active ingredient is the organophosphate Coumophos) to kill the remaining mites and provide an estimate of overall level of mites remaining in the hives. The data presented in Fig. 1a were compiled by normalizing the number of mites caught on the sticky cards over time to the total number of mites that fell throughout the experiment, including in the 1 week after CheckMite+ treatment. Significance was analyzed using t tests (Microsoft Excel).

In vitro thermotolerance selection

Mitospores were either treated with H2O2 or grown on minimal media (Czapek Dox Agar without sucrose: NaNO3 0.2%, K2HPO4 0.1%, MgSO4 0.05%, KCl 0.05%, FeSO4 0.001%, Bacto Agar 1.5%) with or without chitin (4 g chitin/1 L). Spores treated with H2O2 were submerged in a 0.3% or 0.03% H2O2 solution for 60 min. The solution was prepared fresh before use and spores were covered during the treatment to prevent light degradation of H2O2. After 60 min, the spores were rinsed three times with sterile water before plating on MEA. Agar plates (95 mm; 10 for each treatment) were inoculated with 1 × 105 mitospores mL−1 and allowed to grow to sporulation. Plates were incubated at successively increasing temperatures, starting at 27 °C and rising to 35 °C in one degree increments over eight generations.

Field trials

Stationary apiary establishment and maintenance

A stationary apiary consisting of 48 full-sized colonies was established in Moscow, Idaho in April 2017 for long-term field treatment and selection experiments. To limit contact with pesticides and diseased bees from other operations, these hives did not participate in any migratory commercial pollination activity. The field site was within 2 km proximity to urban areas and farms with other small honey bee operations which may have served as sources for mite and pathogen inoculation into our hives. All hives were started using new hive woodware (hive boxes, bottom boards, and lids) and new “two-pound packages” of bees (0.91 kg or ~ 7000 worker bees and a mated queen) from the same commercial bee supplier based in California, USA. Hives were started with two frames of honey, three frames of foundation, four frames of empty drawn comb, and a one-gallon (3.8 L) feeder for sucrose solution feeding during times of low floral abundance.

The hives were placed into four clusters at least 20 m apart with plots of pine trees serving as barriers between clusters. Each cluster contained 12 hives in a horseshoe pattern, with individual hives being spaced 2–3 m apart. Hive entrances were marked with unique color and texture patterns to reduce drift of workers between colonies. The apiary was monitored regularly for 6–8 weeks to ensure all colonies had established and were of approximately similar sizes and health before beginning field tests. During this establishment phase, frames of brood were occasionally moved from strong hives to weak hives to equalize hive populations. Hives were maintained with minimal beekeeper intervention but frequent hive monitoring. Because a swarming event would have considerably affected mite levels, queen cells were removed and honey supers were added as needed. Hives were monitored for brood and frame number to determine what, if any, negative effects treatment might have on colony health.

To prevent colonies that were succumbing to intense Varroa infestation from spreading their infections to neighboring hives, hives that were measured to be over 15 mites per 100 bees (five times higher than the treatment threshold) in ethanol samples were removed from the apiary and considered functionally dead for the experiment.

Stationary apiary treatment

The colonies in the stationary apiary received either treatment with sporulating Metarhizium on MEA agar discs (N = 24) or uninoculated MEA agar discs as a control (N = 24). Hemocytometer counts in the laboratory showed that each Metarhizium treatment plate contained on average 8.76 × 108 spores. Hives were treated every 4 weeks over the course of the 2017 and 2018 field seasons. Treatment consisted of inverting Petri dishes (95 mm × 15 mm plates) and removing the agar discs onto the top bars of the honey comb of the hives, one disc for each hive box. Hemocytometer counts in the laboratory showed that each plate contained on average 8.76 × 108 spores.

Stationary apiary data collection and analysis

Varroa mite population levels in the stationary apiary were assayed twice the first year (July, November) and four times the second year (April, June, August, September) using ethanol sampling of adult bees (after Dietemann63, but with increased shaking time to dislodge mites). In addition, bottom board sticky cards were maintained continuously throughout the field season to capture all Varroa dying in the hive. The sticky cards were 46 cm × 33 cm cardstock with a thin layer of petroleum jelly (Vaseline) applied to the top side. A screen made from 3.18 mm mesh hardware cloth was placed over the card; bees could walk on the screen, while dead mites and small hive debris could fall through onto the card. Sticky cards were changed every 3 days for the first 15 days after treatment, and then every 7 days until the next treatment. For each card, the number of dead mites were counted, and 12 mites were selected to be analyzed for mycoses. Mites were surface sterilized with 95% ethanol to minimize the possibility of growing Metarhizium that was external on mite bodies rather than fungus that had internally infected mites. Surface-sterilized mites were then plated onto 1/4 strength PDA + streptomycin/penicillin antibiotics and incubated at 25 °C until fungal growth was visible. Mites that grew Metarhizium colonies after surface sterilization were considered to have died by mycosis. Spores from Metarhizium colonies that grew out of mites in these cultures were collected with a dissecting needle and transferred to a 0.01% Tween 80 solution; 15 µL of this solution was spread onto an MEA plate to create the next generation of treatments. Honey bee colony mortality differences were analyzed with OASIS 264. Mantel-Cox tests were used to determine significant differences in mortality between treatments.

Mitospore germination/germination tube

Metarhizium colonies were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA). Mitospores were harvested after 2 weeks of growth using a sterile microbiological loop and transferred to a 0.01% Tween 80 solution. Mitospore suspensions (105 mitospores mL−1) were shaken using a vortex for 30 s before dropping, without spreading, 30 µL onto 20 mL of 1/4 PDA medium in polystyrene petri dishes (95 mm × 15 mm). Three different mitospore samples were inoculated onto each petri dish. Samples were incubated for 24 h at 35 °C in the dark, an environment that most closely simulates the honey bee hive. Three drops of lactophenol cotton blue stain was added after 24 h, to fix and stain mitospores and prevent further germination. The droplets were covered with a coverslip and examined under a light microscope at 400× magnification. Mitospores were considered germinated if the germ tube was longer than the length of the mitospore65. A minimum of 300 mitospores were observed per sample and the percent germination was calculated according to Braga et al.65. Germ tube length was measured for a minimum of 300 mitospores per sample using Zen software (Carl Zeiss AG).

Metarhizium JH1078 and oxalic acid comparison

In June of 2020, 20 hives in an apiary near Moscow, Idaho were chosen at random to receive Metarhizium JH1078 or oxalic acid treatments. Metarhizium inoculum was grown on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) at room temperature to sporulation (~ 20 days). Organic short grain brown rice (Lundberg Family Farms, Richvale, California) was rinsed and then soaked in 82.2 °C water for 15 min. 3 kg of hydrated grain was then transferred to fungal grow bags (Unicorn Corp.) and sterilized in an autoclave. After cooling, the bags were inoculated with spores from the starting culture by tapping the agar plates upside down over the opening of the bag. The bags were shaken to evenly distribute the spores. Bag cultures were grown to sporulation, and then the sporulating grain was transferred into 7 cm × 10 cm banana fiber bags with 3.18 mm mesh. Oxalic acid treatment was prepared as a 2.8% oxalic acid solution in 1:1 (w/v) sucrose syrup. Five milli litre of this solution was dripped in the gaps between all frames in the hive that were covered with bees. Mite levels were measured with ethanol washes at the start and end of the experiment.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sylena Harper, Fadime Yetis, and Rodrigo Guizar for their technical support in the field and laboratory. This work was funded in part by the WWW Foundation under direction by Bryce, Emery, and Adam Rhodes; Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA) Specialty Crop Block Grant K2531; the Thurber Endowment for Pollinator Ecology; and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch 1007314.

Author contributions

J.O.H., N.L.N., L.M.C., and W.S.S. designed the research. J.O.H., N.L.N., and B.K.H. performed the research. P.E.S. and D.S. provided live cultures and valuable discussion. J.O.H. provided all images used. J.O.H. and N.L.N. analyzed the data. J.O.H., N.L.N., and W.S.S. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. A type specimen of M. brunneum JH1078 has been deposited in the United States Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (NRRL), accession number NRRL 68016.

Competing interests

J.O.H., N.L.N, L.M.C., and W.S.S. have filed for intellectual property associated with strain JH1078 and the methods used to produce it. B.K.H., D.S., and P.E.S. declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-89811-2.

References

- 1.Glare TR, et al. Have biopesticides come of age? Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leahy, J., Mendelsohn, M., Kough, J., Jones, R. & Berckes, N. Biopesticide oversight and registration at the US Environmental Protection Agency. In Biopesticides: State of the Art and Future Opportunities (eds Gross, A. D. et al.) 3–18 (American Chemical Society Symposium Series, 2014).

- 3.Arthurs S, Dara SK. Global status of microbial control programs and practices. J. Invert. Pathol. 2019;165:3. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubovskiy M, et al. Can insects develop resistance to insect pathogenic fungi? PLoS One. 2013;8:e60248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damalas CA, Koutroubas SD. Current status and recent developments in biopesticide use. Agriculture. 2018;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts DW, Campbell AS. Stability of entomopathogenic fungi. Misc. Publ. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1977;10(3):19–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovett B, St. Leger RJ. Stress is the rule rather than the exception for Metarhizium. Curr. Genet. 2015;61:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortiz-Urquiza A, Luo Z, Keyhani NO. Improving mycoinsecticides for insect biological control. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:1057–1068. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthoud H, Imdorf A, Haueter M, Radloff S, Neumann P. Virus infections and winter losses of honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera) J. Apic. Res. 2010;49(1):60–65. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Conte Y, Ellis M, Ritter W. Varroa mites and honey bee health: Can Varroa explain part of the colony losses? Apidologie. 2010;41:353–363. doi: 10.1051/apido/2010017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Engelsdorp D, Meixner MD. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J. Invert. Pathol. 2010;103:S80–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray EL. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science. 2015;347:6229. doi: 10.1126/science.1255957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KV, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2013–2014 annual colony losses in the USA. Apidologie. 2015;46:292–305. doi: 10.1007/s13592-015-0356-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinhauer NA, et al. A national survey of managed honey bee 2012–2013 annual colony losses in the USA: Results from the Bee Informed Partnership. J. Apic. Res. 2014;53:1–18. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.53.1.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boecking O, Genersch E. Varroosis—the ongoing crisis in bee keeping. J. Consum. Protect. Food Saf. 2008;3(2):221–228. doi: 10.1007/s00003-008-0331-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallai N, Salles J-M, Settele J, Vaissière BE. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. J. Ecol. Econ. 2009;68:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey SD, et al. Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019;116:1792–1801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818371116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YP, Siede R. Honey bee viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2007;70:33–80. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(07)70002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drummond F, et al. Managed pollinator CAP coordinated agricultural project: The first two years of the stationary hive project: Abiotic site effects. Am. Bee J. 2012;152(4):369–372. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodwin RM, Taylor MA, Mcbrydie HM, Cox HM. Drift of Varroa destructor infested worker honey bees to neighbouring colonies. J. Apicult. Res. 2006;45(3):155–156. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2006.11101335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kralj J, Brockmann A, Fuchs S, Tautz J. The parasitic mite Varroa destructor affects non-associative learning in honey bee foragers, Apis mellifera L. . J. Comp. Physiol. 2007;193:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00359-006-0192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeley TD, Smith ML. Crowding honeybee colonies in apiaries can increase their vulnerability to the deadly ectoparasite Varroa destructor. Apidologie. 2015;46:716–727. doi: 10.1007/s13592-015-0361-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolan MP, Delaplane KS. Distance between honey bee Apis mellifera colonies regulates populations of Varroa destructor at a landscape scale. Apidologie. 2017;48:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s13592-016-0443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallner K. Varroacides and their residues in bee products. Apidologie. 1999;30:235–238. doi: 10.1051/apido:19990212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mullin CA, et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: Implications for honey bee health. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulton CA, Huff Hartz KE, Reeve JD, Lydya MJ. An examination of exposure routes of fluvalinate to larval and adult honey bees (Apis mellifera) Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2019;38:1356–1363. doi: 10.1002/etc.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berry JA, Hood WM, Pietravalle S, Delaplane KS. Field-level sublethal effects of approved bee hive chemicals on honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) PLoS One. 2013;8:76536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boncristiani H, et al. Direct effect of acaricides on pathogen loads and gene expression levels in honey bees Apis mellifera. J. Insect Physiol. 2012;58:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neal ST, Brewster CC, Bloomquist JR, Anderson TD. Amitraz and its metabolite modulate honey bee cardiac function and tolerance to viral infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017;149:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Locke B, Forsgren E, Fries I, de Miranda JR. Acaricide treatment affects viral dynamics in Varroa destructor infested honey bee colonies via both host physiology and mite control. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:227–235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haarmann T, Spivak M, Weaver D, Weaver B, Glenn T. Effects of fluvalinate and coumaphos on queen honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in two commercial queen rearing operations. J. Econ. Entomol. 2002;95:28–35. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-95.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettis JS, Collins AM, Wilbanks R, Feldlaufer MF. Effects of coumaphos on queen rearing in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Apidologie. 2004;35:605–610. doi: 10.1051/apido:2004056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins M, Pettis JS, Wilbanks R, Feldlaufer MF. Performance of honey bee (Apis mellifera) queens reared in beeswax cells impregnated with coumaphos. J. Apic. Res. 2004;43:128–134. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2004.11101123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burley LM, Fell RD, Saacke RG. Survival of honey bee (hymenoptera: Apidae) spermatozoa incubated at room temperature from drones exposed to miticides. J. Econ. Entomol. 2008;101:1081–1087. doi: 10.1093/jee/101.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins M, Pettis JS. Correlation of queen size and spermathecal contents and effects of miticide exposure during development. Apidologie. 2013;44:351–356. doi: 10.1007/s13592-012-0186-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson RM, Pollock HS, Berenbaum MR. Synergistic interactions between in-hive miticides in Apis mellifera. J. Econ. Entomol. 2009;102:474–479. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forkpah C, Dixon LR, Fahrbach SE, Rueppell O. Xenobiotic effects on intestinal stem cell proliferation in adult honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) workers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhooria S, Agarwal R. Amitraz, an underrecognized poison: A systematic review. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016;144:348–358. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.198723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knowles CO, Gayen AK. Penetration, metabolism and elimination of amitraz and N-(2,4-dimethylphenyl)-N-methylformamidine in Southwestern corn borer larvae (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 1983;76:410–413. doi: 10.1093/jee/76.3.410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krupke CH, Hunt GJ, Eitzer BD, Andino G, Given K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez-Cabrera J, et al. A single mutation is driving resistance to pyrethroids in European populations of the parasitic mite, Varroa destructor. J. Pest Sci. 2018;91:1137–1144. doi: 10.1007/s10340-018-0968-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettis JS. A scientific note on Varroa destructor resistance to coumaphos in the United States. Apidologie. 2004;35:91–92. doi: 10.1051/apido:2003060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elzen PJ, Baxter JR, Spivak M, Wilson WT. Amitraz resistance in Varroa: New discovery in North America. Am. Bee J. 1999;139:362. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chandler D, et al. Fungal biocontrol of Acari. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2000;10:357–384. doi: 10.1080/09583150050114972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanga LHB, James RR, Boucias DG. Hirsutella thompsonii and Metarhizium anisopliae as potential microbial control agents of Varroa destructor, a honey bee parasite. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2002;81:175–184. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2011(02)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meikle WG, Mercadier G, Holst N, Nansen C, Girod V. Impact of a treatment of Beauveria bassiana (Deuteromycota: Hyphomycetes) on honeybee (Apis mellifera) colony health and on Varroa destructor mites (Acari: Varroidae) Apidologie. 2008;39:247–259. doi: 10.1051/apido:2007057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez M, Gerding M, France A, Ceballos R. Evaluation of Metarhizium anisopliae var anisopliae qu-M845 isolate to control Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in laboratory and field trials. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2009;69:541–547. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanga LHB, Adamczyk J, Patt J, Gracia C, Cascino J. Development of a user-friendly delivery method for the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae to control the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor in honey bee, Apis mellifera, colonies. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010;52:327–342. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanga LHB, Jones WA, James RR. Field trials using the fungal pathogen, Metarhizium anisopliae (Deuteromycetes: Hyphomycetes) to control the ectoparasitic mite, Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in honey bee, Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies. J. Econ. Entomol. 2003;96:1091–1109. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-96.4.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanga LHB, Jones WA, Gracia C. Efficacy of strips coated with Metarhizium anisopliae for control of Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) in honey bee colonies in Texas and Florida. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2006;40:249. doi: 10.1007/s10493-006-9033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.James RR. Microbial control for invasive arthropod pests of honey bees. In: Hajek AE, Glare TR, O’Callaghan M, editors. Progress in Biological Control, Use of Microbes for Control and Eradication of Invasive Arthropods. Springer; 2009. pp. 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraus B, Velthuis HHW, Tingek S. Temperature profiles of the brood nests of Apis cerana and Apis mellifera colonies and their relation to Varroosis. J. Apic. Res. 1998;37:175–181. doi: 10.1080/00218839.1998.11100969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodríguez M, Gerding M, France A. Selection of entomopathogenic fungi to control Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae) Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2009;69:534–540. [Google Scholar]

- 54.James RR, Hayes G, Leland JE. Field trials on the microbial control of Varroa with the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Am. Bee J. 2006;146:968–972. [Google Scholar]

- 55.St. Leger RJ, Wang C. Genetic engineering of fungal biocontrol agents to achieve greater efficacy against insect pests. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:901–907. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2306-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stamets, P. Mycoattractants and mycopesticides, U.S. Patent No. 8501207B2. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (2013).

- 57.Lovett B, St Leger RJ. Genetically engineering better fungal biopesticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:781–789. doi: 10.1002/ps.4734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rangel DEN, Anderson AJ, Roberts DW. Growth of Metarhizium anisopliae on non-preferred carbon sources yields conidia with increased UV-B tolerance. J. Invert. Pathol. 2006;93:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ibrahim L, Butt TM, Jenkinso P. Effect of artificial culture media on germination, growth, virulence and surface properties of the entomopathogenic hyphomycete Metarhizium anisopliae. Mycol. Res. 2002;106(6):705–715. doi: 10.1017/S0953756202006044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nahar PB, et al. Effect of repeated in vitro sub-culturing on the virulence of Metarhizium anisopliae against Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2008;18:337–355. doi: 10.1080/09583150801935650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peck DT, Seeley TD. Mite bombs or robber lures? The roles of drifting and robbing in Varroa destructor transmission from collapsing honey bee colonies to their neighbors. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):0218392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gregorc A, Knight PR, Adamczyk J. Powdered sugar shake to monitor and oxalic acid treatments to control Varroa mites (Varroa destructor Anderson and Trueman) in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies. J. Apic. Res. 2017;56:71–75. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2017.1278912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dietemann V, et al. Standard methods for Varroa research. J. Apic. Res. 2013;52(1):1–54. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han SK, et al. OASIS 2: Online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56147–56152. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braga GUL, Flint SD, Messias CL, Anderson AJ, Roberts DW. Effect of UV-B on conidia and germlings of the entomopathogenic hyphomycete Metarhizium anisopliae. Mycol. Res. 2001;105(7):874–882. doi: 10.1017/S0953756201004270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. A type specimen of M. brunneum JH1078 has been deposited in the United States Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection (NRRL), accession number NRRL 68016.