Abstract

Deep fungal infections rarely involve the oral cavity and most commonly affect immunocompromised patients. Oral deep fungal infections typically manifest as chronic mucosal ulcerations or granular soft tissue overgrowths. Since these lesions are non-specific and can mimic malignancy, it is crucial to obtain a thorough clinical history and an adequate biopsy to render the appropriate diagnosis. We report four new cases of deep fungal infections, diagnosed as histoplasmosis, blastomycosis and chromoblastomycosis, exhibiting unique oral and perioral presentations. Awareness of these unusual entities can help dental and medical practitioners expedite proper multidisciplinary care and minimize morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Invasive fungal infections, Mycoses, Oral, Mouth, Blastomycosis, Histoplasmosis, Chromoblastomycosis

Introduction

Fungal infections may present as superficial cutaneous or mucosal disease, with evidence of local invasion or as more serious disseminated systemic infections [1]. While candidiasis is the most common superficial fungal infection routinely encountered in the oral cavity, deep fungal infections can also occur intraorally. Associated risk factors include immunodeficiency, use of immunosuppressive/immune-modulatory medications or chemotherapeutic agents [2]. Fortunately, when the host has an intact immune system, exposure to fungal organisms typically does not progress to infection [1]. Herein, we present four challenging cases of deep fungal infection involving the oral and perioral mucosa. Awareness of these varied clinical presentations, their unique occurrence in immunocompetent individuals, and the importance of supportive medical management are highlighted in this case series. This study was approved by The Ohio State University Biomedical Sciences Institutional Review Board (Study ID 2019H0451).

Case 1

A 72-year-old male presented to the head and neck surgical oncology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcers involving the oral commissures bilaterally. The patient reported that these lesions had been present for one month with gradual increase in size. Oral intake was limited due to increasing pain, which resulted in a 40 lb. weight loss. A course of Augmentin and topical application of Vaseline failed to improve his condition. His past medical history was significant for shortness of breath and a cutaneous malignancy of the right infraorbital region, which had been surgically excised 6 months previously without evidence of recurrence. The patient was a former smoker and consumed alcohol occasionally.

Extraoral examination revealed deep ulcerations with indurated borders bilaterally involving the oral commissures with significant destruction of the perioral facial skin (Fig. 1a). No evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy was noted on manual palpation. With a clinical diagnosis of ulcerated angular cheilitis, an incisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Histopathologic evaluation showed chronically inflamed granulation tissue and staining by the Grocott–Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) method revealed numerous yeast forms, consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum (Fig. 1b, c). Serum studies confirmed the presence of histoplasma antigen. Systemic itraconazole (100 mg twice daily) was initiated and complete resolution of the ulcerations was noted after 2 months of treatment (Fig. 1d). The patient remained free of disease at 1-year follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Initial presentation of deep ulcerations at the oral commissures bilaterally (a) H&E* and GMS** stained sections showing granulation tissue in association with numerous yeast forms consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum: × 600 (b, c) and complete resolution of the ulcers following 2 months of antifungal therapy (d). *Hematoxylin and eosin **Grocott–Gomori methenamine silver

Case 2

A 49-year-old male presented for evaluation of a non-healing extraction socket of the left posterior mandible of 1-month duration. He also reported paresthesia of the left mandible and left lower face. The patient had previously visited his general dentist and was prescribed multiple rounds of antibiotics without resolution. The patient’s medical history was significant for renal cell carcinoma treated with complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney 7 months prior. He reported shortness of breath and a 25 lb. unintentional weight loss over the past 6 months. He was not taking any medications, had no known drug allergies, was a never smoker and used alcohol occasionally.

Extraoral examination revealed tender lymphadenopathy of the left submandibular region. Intraoral examination showed an exophytic soft tissue mass extruding from the extraction sockets of teeth #20 and #21, with significant mobility of the adjacent dentition. The mass was tender on palpation, ulcerated and exhibited purulent discharge (Fig. 2a). A periapical radiograph showed an ill-defined radiolucency with loss of the lamina dura around teeth #22–24 (Fig. 2b), concerning for metastatic renal cell carcinoma or a second primary malignancy. An incisional biopsy was performed and showed subacutely inflamed granulation tissue with multinucleated giant cells and occasional large yeast forms, consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis (Fig. 2c, d). The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who ordered a chest computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast, which showed numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules. Serum and urine analyses revealed the presence of Blastomyces antigen. The patient was prescribed itraconazole (200 mg twice daily), which clinically resulted in soft tissue healing, however progressive bony destruction of the mandible was noted radiographically (Fig. 2e, f). The patient experienced increasing pain with difficulty masticating and a pathologic jaw fracture ensued. Surgical resection with plate reconstruction was initially performed (Fig. 2g), followed by definitive reconstruction with a fibula free flap completed 14 months subsequently.

Fig. 2.

Ulcerated, granular proliferation at the extraction site of teeth #20–21 (a) periapical radiograph of tooth #22 showing an irregular radiolucency with widened PDL and loss of lamina dura (b) H&E and GMS stained sections showing subacutely inflamed granulation tissue and necrotic debris in association with large and occasionally budding yeast forms consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis: × 600 (c, d) clinical resolution of the soft tissue lesion with persistent bone destruction 2 months after initiation of antifungal treatment (e, f) and post-operative panoramic radiograph depicting surgical resection with plate reconstruction (g)

Case 3

A 39-year-old female presented with a palatal mass of 2 years duration with recent onset of pain over the previous month. Her medical history was significant for type II diabetes under fair control and gastroesophageal reflux disease. She had never smoked and did not consume alcohol. She had previously undergone an extensive medical work-up with upper GI endoscopy, routine blood work, diverse laboratory studies (including HIV antibody / antigen testing and rapid plasma reagin, which were negative) and two palatal biopsies. The most recent biopsy performed 1-year prior showed epithelial hyperplasia and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, with no evidence of microorganisms identified on special stains. The initial sample revealed marked acute inflammation, focal abscess and reactive epithelial changes.

On clinical examination, an erythematous, granular, exophytic mass measuring 2.0 × 1.5 cm was noted on the anterior hard palate, just right of the midline (Fig. 3a). It felt spongy and was tender on palpation. Tooth #7 showed a pinkish-grey discoloration and teeth #7 and #8 were deemed necrotic on vitality testing. A limited field of view cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan revealed a well-defined, irregular radiolucency apical to tooth # 7 with mild external root resorption (Fig. 3b). The lesion extended superiorly and posteriorly with marked erosion of both the palatal cortical bone and floor of the nasal fossa (Fig. 3b, inset). An incisional biopsy was performed through a focal buccal bone dehiscence and intra-operative findings showed abundant necrotic debris filling a bony cavity within the maxilla (Fig. 3c), which appeared to extend from the pyriform rim superior to tooth #8 to the anterior right palate with broad perforation of the palatal cortical bone. Histopathologic evaluation revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the surface epithelium with prominent leukocytic exocytosis. The underlying connective tissue supported collections of epithelioid histiocytes consistent with granuloma formation, some of which exhibited central necrosis. A significant portion of the specimen was composed of extensive tissue necrosis containing neutrophilic debris, as well as occasional refractile and budding yeast forms exhibiting double-contoured walls with a diameter of approximately 15 μm noted by GMS staining (Fig. 3d, e). These findings were most consistent with a deep fungal infection with morphologic features suggestive of blastomycosis. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further evaluation and antibodies directed against Blastomyces were detected in serum and urine analyses. Daily itraconazole (Tolsura; 130 mg daily) was initiated and increased to 260 mg daily at 3 months. At 5 months follow-up, a 4 × 3 mm mucosal depression with a fully epithelialized surface was present on the right palate (Fig. 3f). Despite clinical resolution of the soft tissue mass, imaging studies revealed persistence of the large maxillary defect which exhibited no appreciable bone fill. The patient was asymptomatic and refused further surgical intervention. She continues radiographic observation and daily itraconazole for a planned duration of 1 year.

Fig. 3.

Granular soft tissue mass affecting the anterior hard palate (a) CBCT showing an osteolytic process of the anterior maxilla with cortical bone destruction (b) buccal bone dehiscence and tissue necrosis observed upon surgical exploration (c) H&E and GMS stained sections showing large yeast forms consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis in a background of extensive tissue necrosis: × 600 (d, e) and clinical resolution of the soft tissue mass following 4 months of itraconazole therapy (f)

Case 4

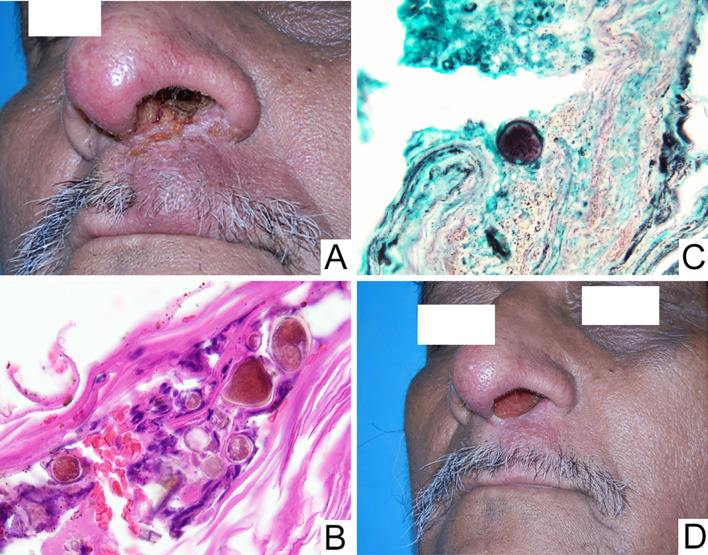

A 59-year-old male presented with a 2-year history of tender swelling of the upper lip. This reportedly began as a pinpoint crusted lesion at the left base of the nose with gradual onset of soft tissue swelling. A previous incisional biopsy showed chronic inflammation with non-caseating granuloma formation. It is unknown whether special stains for microorganisms were performed on those histologic sections. Subsequent management with a nasal steroid (betamethasone) and mupirocin reportedly yielded a modest decrease in size. The patient was on no additional medications and had no significant medical history.

Clinical examination revealed diffuse soft tissue swelling of the cutaneous aspect of the upper lip, just left of the midline. Mild superficial crusting extended from the ipsilateral nasal orifice to the lip vermilion (Fig. 4a). Given the clinical history and geographic region where the patient was residing (Honduras), the possibility of a specific infection such as leishmaniasis was suspected and a repeat biopsy was performed.

Fig. 4.

Tender lip swelling with superficial crusting extending into the nasal orifice (a) H&E and GMS stained sections showing large, pigmented yeast forms with irregular “cerebriform” conformation, consistent with Chromoblastomycosis: × 600 (b, c) and incomplete clinical resolution after 1 year of daily itraconazole and terbinafine (d)

Histopathologic assessment revealed an ulcerated surface epithelium exhibiting prominent superficial hemorrhagic and keratinaceous crusting. The underlying connective tissue supported a heavy influx of chronic inflammatory cells exhibiting numerous collections of epithelioid histiocytes associated with occasional multinucleated giant cells and a dense lymphocytic infiltrate. Focal large diameter (20–40 μm) pigmented yeast forms exhibiting an irregular cerebriform or “muriform” conformation were focally identified in the superficial keratin as well as deeper within the sample (Fig. 4b, c). A final diagnosis of ulcerated, non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation consistent with a deep fungal infection suggestive of chromoblastomycosis was rendered. Further medical evaluation with culture confirmed this diagnosis and combination antifungal therapy, comprised of 100 mg itraconazole and 500 mg terbinafine daily, was initiated. While dramatic improvement was noted at 1-year follow-up, complete resolution was not attained (Fig. 4d).

Discussion

Many fungal organisms, such as H. capsulatum, B. dermatitidis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, and Cryptococcus neoformans, have a predilection for lung involvement and can cause acute or chronic respiratory illness [3, 4]. Deep mycoses are relatively rare in the oral region and are thought to arise from either local inoculation or dissemination by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. As defined by the Fungal Infections Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and Mycoses Study Group of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (EORTC/IFICG), diagnosis of a disseminated mycosis requires either a positive blood culture result or antigen detection in urine or serum [5, 6]. Deep fungal infections of the oral cavity and perioral structures have been reported in a variety of anatomic sites, including the alveolar processes, palate, tongue, buccal mucosae, lips and maxillary sinuses [1, 7–10]. In the current series, we discuss four unique cases of Histoplasmosis, Blastomycosis and Chromoblastomycosis presenting with oral or perioral lesions.

Histoplasmosis was first described by Samuel Darling in 1905. It is caused by H. capsulatum, a saprophyte and dimorphic fungus, and is commonly seen in patients living along the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys [9, 11]. Although this infection is considered endemic to this region, it is now also being reported in non-endemic zones and has become an emerging infection worldwide [12]. The organisms are present in soil enriched with bird or bat droppings [13]. Their spores may become aerosolized and inhaled, establishing pulmonary infections with a broad range of severity. While the majority of cases result in an asymptomatic, self-limiting reaction, some patients may experience symptomatic acute or chronic pulmonary infections. Typical signs and symptoms are non-specific and can include fever, malaise, weight loss, chest pain, cough and shortness of breath [14–16]. The chronic form closely resembles tuberculosis and individuals with a compromised immune status are at greatest risk for developing this infection [11]. Additional contributing factors include agricultural or construction work, street cleaning and recreational activities such as exploring caves or fishing [9, 11].

Histoplasmosis is primarily a lung disease, which is most often asymptomatic and may be identified on routine imaging studies as the presence of calcified hilar lymph nodes [4, 8]. It is estimated that less than 0.5% of patients with acute infection develop progressive disseminated disease, though a reliable estimate of incidence has not been defined in part due to reporting bias [17]. Disseminated disease is the predominant form in solid organ transplant recipients and occurs in up to 5% of patients with HIV in endemic regions [14, 15, 18, 19]. Oral histoplasmosis is considered rare across all forms of the infection; however, it has been reported to occur in 20–76% of patients with progressive disseminated disease [11, 13, 20]. Very rarely, oral lesions may be the only sign of infection, supporting a diagnosis of primary oral histoplasmosis [11]. Intraorally, the most common sites of involvement include the tongue, palate, gingiva and buccal mucosa [21–23]. Interestingly, only one case mimicking angular cheilitis has been reported previously in the English language literature [24]. Oral lesions usually occur as nodules, plaque-like granular proliferations or deep, non-remitting ulcers [11, 12, 25, 26]. The ulcero-proliferative lesions usually have firm, rolled borders and closely mimic a malignant process [27, 28]. Rare cases have shown alveolar bone involvement with progressive lesions simulating osteomyelitis or periodontal disease [11, 13]. The clinical differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma, syphilitic chancre, oral involvement of tuberculosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and major aphthous ulcer [8, 9]. The diagnosis is typically established with incisional biopsy, fungal cultures, and antigen and/or antibody testing of serum or urine [6, 11, 14]. Inadequate tissue sampling may lead to an incorrect diagnosis [27]. Systemic therapy with liposomal Amphotericin-B remains a mainstay treatment for patients with disseminated disease, particularly in immunocompromised settings [29]. Itraconazole is highly active against H. capsulatum and is the drug of choice for most outpatient treatments [1, 30]. The overall prognosis is variable. Even with treatment, mortality ranges between 2 and 23% for disseminated infection, with the higher rates occurring in an immunocompromised setting [14, 31].

Blastomycosis was first described by Gilchrist in 1894 as an uncommon disease caused by dimorphic fungi B. dermatitidis. In the United States, the estimated annual incidence is 1–2 cases per 100,000 population [32, 33]. Similar to histoplasmosis, blastomycosis is endemic to the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys, and is also identified in areas of Canada and the Mid-western United States surrounding the Great Lakes [34–36]. Other endemic areas include South America, Africa and parts of Asia [36]. The disease is caused by inhalation of aerosolized spores, which are converted to yeast forms in the lungs [35]. Pulmonary infection may be asymptomatic, but most patients with blastomycosis (pulmonary and disseminated) will present with non-specific signs and symptoms which can include hemoptysis, cough, chest pain, dyspnea, night sweats, malaise and fever [33, 37–41]. Extrapulmonary involvement occurs in 25–48% of cases [35, 36, 38, 41]. From the pulmonary focus, infection can disseminate via lymphatic or hematogenous spread to the bones, skin, mucosa, central nervous system, and genitourinary tract [32, 34]. Skin and oral mucosal involvement may also result from direct inoculation [36]. Chronic forms of blastomycosis can be seen in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals [32]. Risk factors include engaging in outdoor recreational activities and living by the waterways [10, 42].

In the head and neck region, the larynx is the most commonly affected site of Blastomyces infection followed by the oral cavity [7]. While oral involvement is unusual, the most frequent intraoral sites include the gingiva, alveolar mucosa and buccal mucosa [34]. Oral lesions may present as granular plaques, ulcers with rolled borders, or soft tissue swellings, which may be accompanied by pain, purulent discharge or lymphadenopathy [7, 32, 34]. Bony involvement of the mandible or maxilla, presenting as a radiolucent lesion or non-healing extraction socket, has also been reported [10]. The clinical differential diagnosis is similar to that for histoplasmosis, and includes other specific infections as well as squamous cell carcinoma, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and major aphthous ulcer [32, 43]. Diagnosis is generally multimodal and established based on histopathologic assessment, tissue culture, sputum or respiratory culture, antigen and/or antibody testing [36]. Unfortunately, diagnostic delays have been reported in up to 40% of patients [37]. Current practice guidelines recommend itraconazole as first-line therapy in non-life-threatening cases [44]. The overall mortality rate is approximately 2–6%, but reaches close to 50% in cases of disseminated Blastomycosis [35, 37, 38]. This further emphasizes the importance of prompt diagnosis.

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic, slowly progressive, non-contagious, granulomatous infection caused by several species of fungi mainly from three genera—Fonsecaea, Pialophora and Cladophialophora [45–47]. It has a worldwide distribution and is commonly seen in tropical and subtropical climates. The disease is endemic in Venezuela; however, the highest incidence is reported in Africa [45, 48]. These slow-growing fungi have a low virulence and a high tolerance to heat [48]. Chromoblastomycosis is mainly acquired by patients engaged in outdoor activities and occupations (i.e. agriculture, wood-cutting, latex gathering, etc.) through inoculation trauma [45, 48]. Familial predisposition has been noted and infection is seen 3.5 times more commonly in members of common ancestry. Genetic factors including HLA A29 have been associated with a tenfold increased risk of acquiring this disease [45]. Skin of the extremities is usually involved and lesions initially present as a scaly papule, which is occasionally pruritic [45, 48]. As the process progresses, warty-appearing lesions may develop and continue to evolve into larger verrucous or “cauliflower-like” growths. Propagation to other sites can occur through self-inoculation or hematogenous/lymphatic dissemination [49]. Although rare, cases of dissemination to the central nervous system and oral cavity have been reported [46, 50].

Histopathologically, chromoblastomycosis is characterized by the presence of sclerotic cells, also called “medlar bodies” or “muriform bodies”, which are globe-shaped, cigar-colored, thick-walled organisms measuring 4–12 μm in diameter [46, 51]. The fungal elements are seen in association with non-necrotizing granulomas and neutrophils. Diagnosis is usually established by microscopic evaluation of soft tissue biopsy and/or culture [52]. Therapeutic agents include itraconazole, terbinafine and 5-flucytosine, however, chromoblastomycosis is often refractory to treatment, especially to monotherapy [45, 46]. Physical methods of removal, including surgical excision, cryosurgery and CO2 laser, have also been used. Despite treatment, 14–70% of cases will persist over 1 year, depending on the therapeutic modality employed and the severity of the condition [50, 53].

Oral involvement of deep fungal infections is unusual and infrequently reported in the dental and medical literature. Hence, clinicians are often unaware of the clinical spectrum of disease, which may lead to delayed diagnosis and negatively impact prognosis. Interestingly, while disseminated fungal infections are generally regarded as exclusive to immunocompromised individuals, all cases in the current series occurred in patients who lacked overt evidence of immune suppression. Moreover, in the first three cases, oral and perioral lesions were the initial sign of serious underlying systemic infections. These unique cases underscore the importance of including deep fungal infection as a potential diagnostic consideration in an appropriate clinical setting, such as persistent ulceration or granular soft tissue mass, regardless of the patient’s immune status. While diagnosis may be initiated in the dental setting, multidisciplinary care with immediate referral to an infectious disease specialist is imperative to optimize management and promote a favorable outcome.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Mark Lustberg, MD, Department of Infectious Diseases at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Enver Ozer, MD, Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Matthew Old, MD, Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Marcus Joy, DDS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Hany Emam, BDS, MS, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, Dr. Leona Ayers, MD, Emeritus Professor, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio and Dr. Timothy Bartholomew, DDS in private practice in Mansfield, Ohio.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Vimi S. Mutalik and Caroline Bissonnette have contributed equally.

References

- 1.Telles DR, Karki N, Marshall MW. Oral fungal infections: diagnosis and management. Dent Clin N Am. 2017;61:319–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnan PA. Fungal infections of the oral mucosa. Indian J Dent Res. 2012;23:650–659. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.107384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abreu e Silva MA, Salum FG, Figueiredo MA, Cherubini K. Important aspects of oral paracoccidioidomycosis—a literature review. Mycoses. 2013;56:189–199. doi: 10.1111/myc.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlos WG, Rose AS, Wheat LJ, Norris S, Sarosi GA, Knox KS, et al. Blastomycosis in Indiana: digging up more cases. Chest. 2010;138:1377–1382. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, Bennett JE, Bille J, Crokaert F, et al. Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:7–14. doi: 10.1086/323335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rucci J, Eisinger G, Miranda-Gomez G, Nguyen J. Blastomycosis of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briody A, Santosh N, Allen CM, Mallery SR, McNamara KK. Chronic ulceration of the tongue. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:744–748. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barket S, Collins B, Halusic E, Bilodeau E. A chronic nonhealing gingival mass. histoplasmosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:491–494. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page LR, Drummond JF, Daniels HT, Morrow LW, Frazier QZ. Blastomycosis with oral lesions. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;47:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akin L, Herford AS, Cicciu M. Oral presentation of disseminated histoplasmosis: a case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mota de Almeida FJ, Kivijarvi K, Roos G, Nylander K. A case of disseminated histoplasmosis diagnosed after oral presentation in an old HIV-negative patient in Sweden. Gerodontology. 2015;32:234–236. doi: 10.1111/ger.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figueira JA, Camilo Junior D, Biasoli ER, Miyahara GI, Bernabe DG. Oral ulcers associated with bone destruction as the primary manifestation of histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:e429–e430. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, Walker RC. Systemic histoplasmosis: a 15-year retrospective institutional review of 111 patients. Medicine (Baltim) 2007;86:162–169. doi: 10.1097/md.0b013e3180679130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Avery RK, Lard M, Budev M, Gordon SM, Shrestha NK, et al. Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients: 10 years of experience at a large transplant center in an endemic area. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:710–716. doi: 10.1086/604712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzer HJF, Burchard G, Cornely OA, Lange C, Rolling T, Schmiedel S, et al. Diagnosis and management of systemic endemic mycoses causing pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2018;96:283–301. doi: 10.1159/000489501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodwin RA, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, Thurman SS, Des Prez RM. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltim) 1980;59:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assi M, Martin S, Wheat LJ, Hage C, Freifeld A, Avery R, et al. Histoplasmosis after solid organ transplant. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1542–1549. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Iguacel R, Kurtzhals J, Jouvion G, Nielsen SD, Llibre JM. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in the HIV population in Europe in the HAART era. Case report and literature review. Infection. 2014;42:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0611-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tompsett R, Portera LA. Histoplasmosis: Twenty years experience in a general hospital. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1976;87:214–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng KH, Siar CH. Review of oral histoplasmosis in Malaysians. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy P, Sutaria MK, Christianson CS, Brasher CA. Oral lesions as presenting manifestation of disseminated histoplasmosis. Report of five cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1970;79:389–397. doi: 10.1177/000348947007900220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folk GA, Nelson BL. Oral histoplasmosis. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:513–516. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0797-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doleschal B, Rödhammer T, Tsybrovskyy O, Aichberger K, Lang F. Disseminated histoplasmosis: a challenging differential diagnostic consideration for suspected malignant lesions in the digestive tract. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10:653–660. doi: 10.1159/000452203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chroboczek T, Dufour J, Renaux A, Aznar C, Demar M, Couppie P, et al. Histoplasmosis: an oral malignancy-like clinical picture. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018;19:45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pincelli T, Enzler M, Davis M, Tande AJ, Comfere N, Bruce A. Oropharyngeal histoplasmosis: a report of 10 cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:e181–e188. doi: 10.1111/ced.13927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iqbal F, Schifter M, Coleman HG. Oral presentation of histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient: a diagnostic challenge. Aust Dent J. 2014;59:386–388. doi: 10.1111/adj.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viswanathan S, Chawla N, D’Cruz A, Kane SV. Head and neck histoplasmosis—a nightmare for clinicians and pathologists! Experience at a tertiary referral cancer centre. Head Neck Pathol. 2007;1:169–172. doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey DS, Loyd JE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825. doi: 10.1086/521259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munante-Cardenas J, de Assis AF, Olate S, Lyrio MC, de Moraes M. Treating oral histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1373–1376. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:115–132. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00027-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruse AL, Zwahlen RA, Bredell MG, Gengler C, Dannemann C, Gratz KW. Primary blastomycosis of oral cavity. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:121–123. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181c4680c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cano MV, Ponce-de-Leon GF, Tippen S, Lindsley MD, Warwick M, Hajjeh RA. Blastomycosis in Missouri: epidemiology and risk factors for endemic disease. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:907–914. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803008987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mincer HH, Oglesby RJ., Jr Intraoral North American blastomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:36–41. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2016;30:247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367–381. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS. Clinical manifestations and treatment of blastomycosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38:435–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McBride JA, Sterkel AK, Matkovic E, Broman AT, Gibbons-Burgener SN, Gauthier GM. Clinical manifestations and outcomes in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients with blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, Meece J. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49–56. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piv081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lohrenz S, Minion J, Pandey M, Karunakaran K. Blastomycosis in southern Saskatchewan 2000–2015: unique presentations and disease characteristics. Med Mycol. 2018;56:787–795. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crampton TL, Light RB, Berg GM, Meyers MP, Schroeder GC, Hershfield ES, et al. Epidemiology and clinical spectrum of blastomycosis diagnosed at Manitoba hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1310–1316. doi: 10.1086/340049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McDonald R, Dufort E, Jackson BR, Tobin EH, Newman A, Benedict K, et al. Notes from the field: blastomycosis cases occurring outside of regions with known endemicity—New York, 2007–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1077–1078. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuzel AR, Lodhi MU, Syed IA, Zafar T, Rahim U, Hanbazazh M, et al. Cutaneous, intranasal blastomycosis infection in two patients from southern West Virginia: diagnostic dilemma. Cureus. 2018;10:e2095. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, Bradsher RW, Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801–1812. doi: 10.1086/588300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez-Blanco M, Hernandez Valles R, Garcia-Humbria L, Yegres F. Chromoblastomycosis in children and adolescents in the endemic area of the Falcon State, Venezuela. Med Mycol. 2006;44:467–471. doi: 10.1080/13693780500543238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fatemi MJ, Bateni H. Oral chromoblastomycosis: a case report. Iran J Microbiol. 2012;4:40–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma A, Hazarika NK, Gupta D. Chromoblastomycosis in sub-tropical regions of India. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s11046-009-9270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, Arenas R. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.López Martínez R, Méndez Tovar LJ. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwal R, Singh G, Ghosh A, Verma KK, Pandey M, Xess I. Chromoblastomycosis in India: review of 169 cases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Procop GW, Pritt BS. Atlas of infectious disease pathology. Northfield: College of American Pathologists; 2018. pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hay R, Denning DW, Bonifaz A, Queiroz-Telles F, Beer K, Bustamante B, et al. The diagnosis of fungal neglected tropical diseases (fungal NTDs) and the role of investigation and laboratory tests: an expert consensus report. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed4040122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang CS, Chen CB, Lee YY, Yang CH, Chang YC, Chung WH, et al. Chromoblastomycosis in Taiwan: a report of 30 cases and a review of the literature. Med Mycol. 2018;56:395–405. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]