Abstract

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) is a rare malignancy that accounts for approximately 1% of all head and neck cancers. This neoplasm is characterized by slow but often relentless growth and dissemination. Our aim was to retrospectively evaluate the clinical-pathological features of patients diagnosed with head and neck AdCC and to identify possible prognostic factors. This retrospective observational study analyzed 87 cases of AdCC of the head and neck. Clinical parameters (tumor size, lymph node and distant metastasis, clinical stage, and survival) were obtained from the records. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. There was a slight predominance of cases diagnosed in female patients (54%). The mean age at diagnosis was 51.5 years. Analysis using Cox’s proportional hazards model considering 10-year disease-specific survival identified histologic pattern and presence of perineural invasion as independent prognostic variables. Primary tumor size and distant metastasis were prognostic predictors of 5- and 10-year disease-free survival. Detailed analysis of the association between clinical-pathological parameters and prognosis can assist professionals with cancer treatment planning and adequate patient management. Considering the long-term aggressive behavior of AdCC, rigorous patient follow-up is important to identify possible locoregional or distant recurrences.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Adenoid cystic carcinoma, Prognostic factors, Survival

Introduction

Malignant salivary gland tumors comprise a heterogenous group with distinct histopathological features and biological behaviors. Their diagnosis and management often represent a challenge [1]. Adenoid cystic carcinoma (AdCC) accounts for approximately 22% of all malignant salivary gland tumors [2, 3]. This neoplasm can be diagnosed in the major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual) and in the minor salivary glands found in the oral mucosa, as well as in the secretory units found throughout the upper aerodigestive tract and other glands (lacrimal) [4]. Although AdCC can occur at different sites in the head and neck region, the major salivary glands are the most affected [1].

Clinically, AdCC is characterized by slow and progressive growth and is often associated with painful symptoms because of its propensity for perineural invasion [5, 6]. The tumor shows a female predilection and is mainly diagnosed in patients at about 50 years of age. However, AdCC can affect patients of all age groups [2, 7]. Local recurrences and late distant metastases are common findings and AdCC is frequently associated with a poor prognosis [3, 6].

Several factors have been suggested as prognostic indicators of AdCC. Previous studies reported that the presence of perineural invasion, histopathological pattern, status of surgical margins, anatomical location, clinical stage, and treatment used are directly associated with the control of the disease and survival [5, 8, 9]. Thus, a survey of updated data on the clinical-pathological profile, therapeutic approach, and recurrence and survival rates of patients with head and neck AdCC is fundamental considering its aggressive biological behavior and grim prognosis.

Within this context, the aim of the present study was to retrospectively evaluate the clinical–pathological features of patients with head and neck AdCC seen at a cancer referral center, as well as to identify parameters associated with the prognosis of these patients.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Issues and Study Design

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liga Norte-Riograndense Contra o Câncer (CEP/LNRCC) (Approval number 1.714.150), and the protocol was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The records of all patients diagnosed with AdCC between 2002 and 2016 were revised and the following data were collected: sex, age anatomical location, clinical stage, histopathological pattern, perineural invasion, surgical margins, treatment modality, recurrence, follow-up, and clinical outcome.

For survival analysis, the parameters were categorized as follows: age ≤ 50 or > 50 years; T stage as small (T1 or T2) or large (T3 or T4); N stage as negative (N0) or positive (N1, N2 or N3); clinical stage as early (stage I/II) or advanced (stage III/IV); histopathological pattern as predominantly cribriform/tubular or solid; perineural invasion as absent or present; surgical margins as negative or positive, and treatment as surgery, surgery combined with radiotherapy, and surgery combined with adjuvant radio/chemotherapy.

All cases were diagnosed by a group of experienced pathologists. The clinical staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 7th edition) was used to classify all cases [10]. Each tumor was examined to determine the proportion of tubular, cribriform or solid patterns. Briefly, tumors with predominantly tubular growth and absence of solid component were classified as tubular pattern; tumors exhibiting predominantly cribriform pattern and less than 30% solid growth were considered as cribriform pattern; and tumors containing > 30% of solid areas were classified as pattern. Neural invasion was defined as invasion of neoplastic cells into the perineural space (perineural) or between nerve fascicles (intraneural), irrespective of the size of the nerve.

Disease-specific survival (DSS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were analyzed based on the extracted data. The DSS was defined as the time between the beginning of treatment and death due to AdCC or the last date of clinical follow-up. The DFS was established as the time between the beginning of treatment and diagnosis of first recurrence (local, regional, or distant) or the last date of follow-up (for cases without recurrences).

Statistical Analyses

The SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) and STATA 12.0 (Stata Corporation, USA) programs were used for statistical analysis. Possible associations between the clinical-pathological variables were investigated using Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ2) and Fisher’s exact test. The survival curves (DSS and DFS) were constructed by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. In multivariate analysis, Cox’s proportional hazards model was applied to determine the hazard ratio (HR) and adjusted hazard ratio (HRa), assuming a 95% confidence interval (CI). A level of significance of 5% (p ≤ 0.05) was adopted for all tests.

Results

Clinicopathological Characteristics and Therapeutic Modality

A total of 3367 cases of malignant head and neck tumors were diagnosed during the study period at the cancer center (excluding tumors in the central nervous system, thyroid and parathyroid and metastases). Among all malignancies, 87 (2.5%) were AdCC. The age of patients with AdCC ranged from 24 to 90 years (mean = 51.5 ± 14.8). Most patients were diagnosed at 50 years or older (n = 45; 51.7%). The most affected anatomical site was the parotid gland (31%). There was a higher incidence of the tumor among women (n = 47; 54.0%), with a male/female ratio of 0.85:1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of patients with head and neck AdCC

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 40 (46.0) |

| Female | 47 (54.0) |

| Age | |

| ≤ 50 years | 42 (48.3) |

| > 50 years | 45 (51.7) |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 51.5 ± 14.8 |

| Primary site | |

| Parotid gland | 27 (31.0) |

| Submandibular gland | 15 (17.2) |

| Palate | 19 (21.8) |

| Tongue | 5 (5.7) |

| Nasal cavity/paranasal sinus/nasopharynx | 10 (11.4) |

| Lacrimal gland | 4 (4.6) |

| Other sites | 7 (8.0) |

| Tumor size (T) | |

| T1 | 23 (26.4) |

| T2 | 21 (24.1) |

| T3 | 14 (16.1) |

| T4 | 29 (33.3) |

| Lymph node metastasis (N) | |

| N0 | 75 (86.2) |

| N1 | 7 (8.0) |

| N2 | 3 (3.4) |

| N3 | 2 (2.3) |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| M0 | 73 (83.9) |

| M1 | 14 (16.1) |

| TNM stage | |

| I | 21 (24.1) |

| II | 17 (19.5) |

| III | 10 (11.5) |

| IV | 39 (44.8) |

| Histopathological pattern | |

| Tubular | 31 (35.6) |

| Cribriform | 36 (41.4) |

| Solid | 20 (23.0) |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Absent | 33 (37.9) |

| Present | 54 (62.1) |

| Surgical margins | |

| Negative | 50 (57.5) |

| Positive | 37 (42.5) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 16 (18.4) |

| Surgery + RT | 38 (43.7) |

| Surgery + ChT | 2 (2.3) |

| Surgery + RT + ChT | 26 (29.9) |

| RT + ChT | 4 (4.6) |

| ChT | 1 (1.1) |

| Recurrence | |

| No | 57 (65.5) |

| Yes | 30 (34.5) |

| Survival statusa | |

| Remission | 40 (49.4) |

| Disease in progression | 12 (14.8) |

| Death caused by tumor | 29 (35.8) |

| Total | 87 (100.0) |

TNM tumor-node-metastasis, RT radiotherapy, ChT chemotherapy

aSix cases had no information regarding survival status

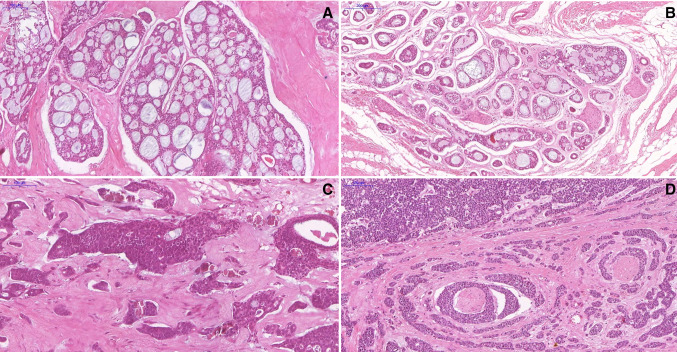

For the clinicopathological analysis, lesions were classified according to the predominant histologic pattern (cribriform, solid, and tubular). The most frequent predominant histologic pattern was the cribriform pattern (n = 36; 41.4%), followed by the tubular (n = 31; 35.6%) and solid (n = 20; 23.0%) patterns (Fig. 1). Perineural invasion was observed in 62.1% (n = 54) of the cases included in the study. Positive margins were found in 42.5% (n = 37) of the cases. The margins were defined as positive if the tumor was located ≤ 5 mm from the resection margin.

Fig. 1.

Microscopic features of AdCC of the head and neck. a Photomicrograph showing a typical AdCC with cribriform features. b Tumor cells arranged in tubular growth pattern. c Histopathological image showing tumor cells arranged in solid pattern. d AdCC solid pattern with perineural invasion

Surgery combined with adjuvant radiotherapy was the most common treatment (n = 38; 43.7%), followed by surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy (n = 26; 29.9%) and surgery alone (n = 16; 18.4%). Regarding radiotherapy, the patients received between 90 and 200 cGy per fraction, with the number of fractions ranging from 20 to 64 (maximum dose of 4000–12,800 cGy). The chemotherapy protocol used in the AdCC cases consisted of different combinations of cisplatin, carboplatin, docetaxel, methotrexate, and paclitaxel.

Lymph node and distant metastases were diagnosed in 13.7% (n = 12) and 16.1% (n = 14) of cases, respectively. The site most affected by metastases was the lung (n = 9; 47.4%), followed by the central nervous system (n = 2; 10.5%), bones (n = 2; 10.5%), and concomitant involvement of bones and liver (n = 2; 10.5%). In our sample, 34.5% of the cases (n = 30) developed recurrences and 35.8% (n = 29) of the patients died from the cancer. The mean time between the initial diagnosis of AdCC and recurrence was 3.4 years. In some cases, recurrence occurred 7 years after the initial diagnosis of AdCC. In cases of death due to AdCC, the mean time between diagnosis and the registration of death was 5.6 years (range 0.4–14.1 years).

With respect to associations between clinical and pathological parameters, tubular and cribriform AdCCs were significantly associated with early clinical stages (p = 0.020), a smaller tumor size (p = 0.009) and absence of distant metastases (p = 0.001), but not with the degree of lymph node involvement (p = 0.098). A predominance of the solid pattern was significantly associated with location in the major salivary gland (p = 0.048). Positive surgical margins were associated with T3/T4 tumors (p < 0.001), lymph node involvement (p = 0.003), distant metastases (p < 0.001), and advanced clinical stage (p < 0.001). Additionally, the presence of perineural invasion was significantly associated with distant metastases (p = 0.014).

Most cases of AdCC with predominant tubular and cribriform patterns had free surgical margins (p = 0.021). The presence of perineural invasion was significantly associated with compromised surgical margins (p = 0.024) but not with the histopathological pattern (p = 0.405).

Analysis of Survival and Prognostic Factors

The DSS and DFS rates were considered for prognostic analysis of patients with AdCC (Tables 2, 3). Among the 81 cases submitted to survival analysis, 10 (12.3%) patients died within 5 years and 27 (33.3%) died within 10 years after the beginning of treatment.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for the 5-year and 10-year DSS in patients (n = 81) with head and neck AdCC

| Parameter | n | 5-year | p | 10-year | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSS (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | DSS (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| ≤ 50 years | 38 | 94.74 (80.56–98.66) | 3.63 (0.77–17.14) | 0.080 | 78.95 (62.29–88.87) | 2.43 (1.06–5.56) | 0.029 |

| > 50 years | 43 | 81.40 (66.22–90.23) | 55.81 (39.85–69.10) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 37 | 89.19 (73.71–95.80) | 1.22 (0.34–4.34) | 0.752 | 56.76 (39.43–70.84) | 0.54 (0.25–1.17) | 0.114 |

| Female | 44 | 86.36 (72.14–93.63) | 75.00 (59.42–85.30) | ||||

| Primary site | |||||||

| Major SG | 43 | 86.05 (71.55–93.48) | 0.75 (0.21–2.66) | 0.659 | 67.44 (51.31–79.25) | 1.07 (0.50–2.29) | 0.844 |

| Minor SG/other sites | 38 | 89.47 (74.34–95.91) | 65.79 (48.48–78.49) | ||||

| Tumor size (T) | |||||||

| T1/T2 | 38 | 94.74 (80.56–98.66) | 3.77 (0.80–17.76) | 0.071 | 86.84 (71.23–94.30) | 4.81 (1.81–12.72) | < 0.001 |

| T3/T4 | 43 | 81.40 (66.22–90.23) | 48.84 (33.34–62.65) | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis (N) | |||||||

| N0 | 69 | 85.51 (74.74–91.93) | a | 0.172 | 68.12 (55.73–77.71) | 1.23 (0.46–3.25) | 0.672 |

| N1/N2/N3 | 12 | a | 58.33 (27.01–80.09) | ||||

| Distant metastasis (M) | |||||||

| M0 | 67 | 97.01 (88.59–99.24) | 27.11 (5.72–128.52) | < 0.001 | 80.60 (68.94–88.24) | 16.15 (7.19–36.24) | < 0.001 |

| M1 | 14 | 42.86 (17.73–66.04) | 7.14 (0.45–27.52) | ||||

| Clinical stage | |||||||

| I/II | 32 | 96.88 (79.82–99.55) | 6.27 (0.79–49.57) | 0.045 | 96.88 (79.82–99.55) | 22.83 (3.09–168.50) | < 0.001 |

| III/IV | 49 | 81.63 (67.67–89.99) | 46.94 (32.59–60.04) | ||||

| Histopathological pattern | |||||||

| Tubular/cribriform | 62 | 93.55 (83.72–97.53) | 5.35 (1.50–18.98) | 0.003 | 77.42 (64.87–85.95) | 3.94 (1.84–8.42) | < 0.001 |

| Solid | 19 | 68.42 (42.79–84.39) | 31.58 (12.91–52.25) | ||||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||

| Absent | 29 | 96.55 (77.9–99.51) | 5.29 (0.67–41.79) | 0.076 | 86.21 (67.31–94.59) | 3.84 (1.32–11.13) | 0.007 |

| Present | 52 | 82.69 (69.38–90.59) | 55.77 (41.32–67.99) | ||||

| Surgical margins | |||||||

| Negative | 44 | 95.45 (83.02–98.84) | 5.26 (1.11–24.78) | 0.018 | 95.45 (83.02–98.84) | 22.45 (5.29–95.24) | < 0.001 |

| Positive | 37 | 78.38 (61.39–88.55) | 32.43 (18.23–47.47) | ||||

| Treatment | |||||||

| Surgery | 12 | 91.67 (53.90–98.78) | 1.83 (0.65–5.17) | 0.403 | 83.33 (48.17–95.55) | 4.20 (1.91–9.25) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery + RT | 36 | 91.67 (76.35–97.23) | 88.89 (73.05–95.68) | ||||

| Surgery + RT + ChT | 26 | 80.77 (59.81–91.51) | 34.62 (17.46–52.48) | ||||

Seven cases were not included in analysis of association between DSS and treatment: two patients submitted to surgery and ChT; four patients submitted to RT and ChT; and one submitted to ChT

Bold values indicate statistically significant results

DSS disease-specific survival, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, SG salivary gland, RT radiotherapy, ChT chemotherapy

aIt was not possible to determine

Table 3.

Univariate analysis for the 5-year and 10-year DFS in patients (n = 81) with head and neck AdCC

| Parameter | n | 5-year | p | 10-year | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFS (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | DFS (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| ≤ 50 years | 38 | 60.53 (43.29–74.00) | 0.88 (0.43–1.79) | 0.734 | 50.00 (33.40–64.52) | 1.01 (0.55–1.86) | 0.954 |

| > 50 years | 43 | 62.79 (46.63–75.29) | 46.51 (31.24–60.44) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 37 | 64.86 (47.30–77.86) | 1.11 (0.54–2.28) | 0.759 | 45.95 (29.55–60.88) | 0.91 (0.49–1.67) | 0.774 |

| Female | 44 | 59.09 (43.19–71.91) | 50.00 (34.59–63.60) | ||||

| Primary site | |||||||

| Major SG | 43 | 67.44 (51.31–79.25) | 1.46 (0.72–2.97) | 0.288 | 53.49 (37.65–66.98) | 1.37 (0.74–2.51) | 0.305 |

| Minor SG/other sites | 38 | 55.26 (38.26–69.34) | 42.11 (26.42–57.00) | ||||

| Tumor size (T) | |||||||

| T1/T2 | 38 | 78.95 (62.29–88.87) | 3.23 (1.44–7.24) | 0.002 | 76.32 (59.42–86.90) | 4.86 (2.31–10.23) | < 0.001 |

| T3/T4 | 43 | 46.51 (31.24–60.44) | 23.26 (12.05–36.60) | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis (N) | |||||||

| N0 | 69 | 63.77 (51.27–73.86) | 1.55 (0.63–3.78) | 0.329 | 52.17 (39.82–63.15) | 1.85 (0.88–3.88) | 0.094 |

| N1/N2/N3 | 12 | 50.00 (20.85–73.61) | 25.00 (6.01–50.48) | ||||

| Distant metastasis (M) | |||||||

| M0 | 67 | 68.66 (56.09–78.30) | 3.07 (1.44–6.54) | 0.002 | 58.21 (45.51–68.94) | 4.30 (2.21–8.36) | < 0.001 |

| M1 | 14 | 28.57 (8.83–52.37) | 7.14 (0.45–27.52) | ||||

| Clinical stage | |||||||

| I/II | 32 | 84.38 (66.46–93.18) | 4.31 (1.65–11.26) | 0.001 | 84.38 (66.46–93.18) | 7.44 (2.90–19.05) | < 0.001 |

| III/IV | 49 | 46.94 (32.59–60.04) | 24.49 (13.60–37.08) | ||||

| Histopathological pattern | |||||||

| Tubular/cribriform | 62 | 64.52 (51.28–75.01) | 1.49 (0.68–3.24) | 0.306 | 54.84 (41.69–66.20) | 1.91 (1.00–3.64) | 0.042 |

| Solid | 19 | 52.63 (28.72–71.88) | 26.32 (9.58 – 46.77) | ||||

| Perineural invasion | |||||||

| Absent | 29 | 72.41 (52.34–85.13) | 1.67 (0.75–3.75) | 0.200 | 65.52 (45.41–79.73) | 2.01 (0.99–4.11) | 0.047 |

| Present | 52 | 55.77 (41.32–67.99) | 38.46 (25.43–51.34) | ||||

| Surgical margins | |||||||

| Negative | 44 | 84.09 (69.50–92.08) | 6.01 (2.57–14.01) | < 0.001 | 81.82 (66.92–90.46) | 10.04 (4.56–22.10) | < 0.001 |

| Positive | 37 | 35.14 (20.40–50.25) | 8.11 (2.09–19.57) | ||||

| Treatment | |||||||

| Surgery | 12 | 75.00 (40.84–91.17) | 1.53 (0.86–2.70) | 0.318 | 75.00 (40.84–91.17) | 2.23 (1.32–3.75) | 0.004 |

| Surgery + RT | 36 | 66.67 (48.83–79.50) | 61.11 (43.35–74.82) | ||||

| Surgery + RT + ChT | 26 | 53.85 (33.29–70.58) | 23.08 (9.38–40.31) | ||||

Seven cases were not included in analysis of association between DFS and treatment: two patients submitted to surgery and ChT; four patients submitted to RT and ChT; and one submitted to ChT

Bold values indicate statistically significant results

DFS disease-free survival, CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, SG salivary gland, RT radiotherapy, ChT chemotherapy

The 5- and 10-years DSS rates were 87.65% (CI 78.27%–93.16%) and 66.67% (CI 55.28%–75.78%), respectively. Table 2 shows the associations between DSS and clinical-pathological variables. At both intervals, the risk of death due to AdCC was significantly higher among cases with distant metastases, advanced clinical stage (III/IV), positive margins, and a predominantly solid histopathological pattern (p < 0.05). Patients older than 50 years (p = 0.029), with T3/T4 tumors (p < 0.001), with evidence of perineural invasion (p = 0.007), or submitted to multiple treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) (p < 0.001) had lower 10-year DSS rates. Patient sex or location of the primary tumor was not significantly associated with DSS.

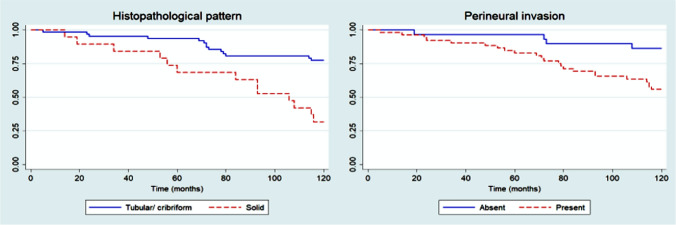

In multivariate analysis of 5-year DSS, no independent prognostic variables could be identified (p > 0.05), possibly because of the limited number of deaths (n = 10) over this follow-up period. Considering 10-year DSS, Cox’s proportional hazards model revealed that histopathological pattern (p = 0.001) and the presence of perineural invasion (p = 0.025) were independent prognostic parameters (Fig. 2; Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for 10-year disease-specific survival rate of patients with head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards model for multivariate analysis of AdCCs

| Parameter | HR (95% CI) | HRa (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSS (10-year) | |||

| Histopathological pattern | 3.94 (1.84–8.42) | 3.55 (1.65–7.61) | 0.001 |

| Perineural invasion | 3.84 (1.32–11.13) | 3.39 (1.16–9.87) | 0.025 |

| DFS (5-year) | |||

| Tumor size (T) | 3.23 (1.44–7.24) | 2.77 (1.21–6.32) | 0.015 |

| Distant metastasis (M) | 3.07 (1.44–6.54) | 2.39 (1.10–5.18) | 0.026 |

| DFS (10-year) | |||

| Tumor size (T) | 4.86 (2.31–10.23) | 4.08 (1.91–8.72) | < 0.001 |

| Distant metastasis (M) | 4.30 (2.21–8.36) | 3.09 (1.57–6.08) | 0.001 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant results

DSS disease-specific survival, DFS disease-free survival, HR hazard ratio, HRa adjusted hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

The following events after the beginning of treatment were considered in the analysis of DFS: recurrence, metastasis (lymph node or distant), and death. The 5- and 10-year DFS rates were 61.73% (CI 50.24–71.31%) and 48.15% (CI 36.95–58.48%), respectively. A significant reduction in DSS was observed in patients with T3/T4 tumors, distant metastases, advanced clinical stage (III/IV), and positive surgical margins 5 and 10 years after the beginning of treatment. The solid pattern (p = 0.042) and perineural invasion (p = 0.047) were associated with lower 5-year DFS. Patients submitted to surgical excision of the tumor combined with radio- and chemotherapy exhibited lower DFS rates than individuals of the other groups (p = 0.004). The remaining clinical-pathological variables were not significantly associated with DFS (Table 3).

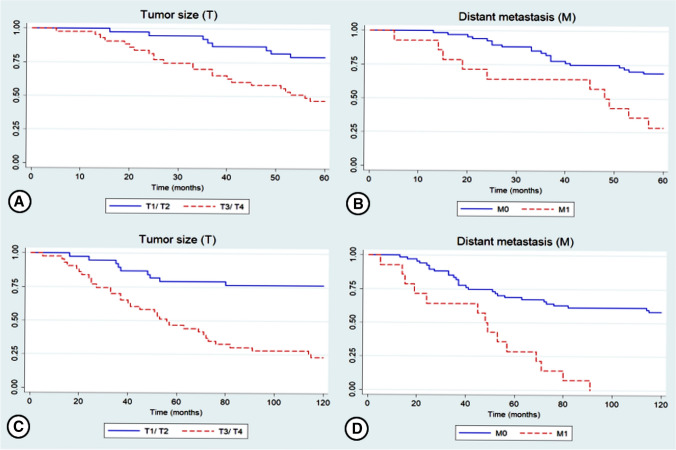

Multivariate analysis using Cox’s proportional hazards model showed that tumor size (T) (p = 0.015) and distant metastasis (M) (p = 0.026) were independent predictors of 5-year DFS. Similarly, analysis of 10-year DFS revealed the independent prognostic value of tumor size (p < 0.001) and presence of distant metastasis (p = 0.001) (Fig. 3; Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for 5-year (a, b) and 10-year (c, d) disease-free survival rate of patients with head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma

Discussion

Among malignant salivary gland tumors, AdCC is characterized by an insidious biological behavior that results in an unfavorable long-term prognosis [11, 12]. In our sample, AdCC cases corresponded to 2.5% of all head and neck malignancies. The most affected anatomical site was the parotid gland. Among cases diagnosed in the minor salivary glands, the palate was the most common site. The present findings agree with those described in the literature [11, 13, 14]. There was a slight female predilection among the cases analyzed here and most patients were diagnosed in their 5th and 6th decades of life.

The term “wolf in sheep’s clothing” is frequently used to characterize AdCC of the head and neck because of its slow but relentless growth and dissemination [15, 16]. Within this context, the identification of clinical-pathological predictors of recurrence and survival in head and neck AdCC is important for a better understanding of this cancer and the consequent prognostic prediction and management of diagnosed cases.

In the present study, lymph node metastasis at diagnosis was observed in 13.7% of the patients. A similar percentage was reported in the recent study of Atallah et al. [17] who evaluated 470 cases of head and neck AdCC. On the other hand, we observed a larger number of cases with distant metastases at diagnosis (16.1%) than those frequently reported in the literature [17, 18]. It should be noted that AdCC is more likely to spread to distant sites than to regional lymph nodes [1].

A decline in long-term survival was observed in our study, with a high death rate due to AdCC (32.1%), demonstrating the aggressive nature of this tumor. Thus, the likelihood of locoregional and distant recurrence is high in AdCC and rigorous long-term follow-up of diagnosed cases is necessary [17, 19, 20]. Univariate analysis considering the short-term prognosis (5 years) showed that distant metastasis (p < 0.001), advanced clinical stage (p = 0.045), histopathological pattern (p = 0.003), and positive surgical margins (p = 0.018) were associated with poor DSS. Furthermore, age (p = 0.029), tumor size (p < 0.001), distant metastasis (p < 0.001), advanced clinical stage (III,IV) (p < 0.001), solid pattern (p < 0.001), perineural invasion (p = 0.007), compromised surgical margins (p < 0.001), recurrence (p = 0.029), and treatment (p < 0.001) had a negative impact on the long-term prognosis (10 years) of the cases analyzed. In multivariate analysis considering 10-year DSS, the solid pattern (p = 0.001) and perineural invasion (p = 0.025) were associated with a poor prognosis. Tumor size (p = 0.015 and p < 0.001) and distant metastasis (p = 0.026 and p = 0.001) were independent predictors of 5- and 10-year DFS, respectively.

The solid pattern is frequently associated with a poor prognosis [20–22], as observed here in the analysis of DSS. In the renowned histopathological grading systems proposed by Perzin et al. [23] and Szanto et al. [24], a frequency of the solid pattern of 30% and 50%, respectively, in histopathological analysis was associated with a poor prognosis. In the recent histopathological grading system developed by van Weert et al. [21], the authors considered the presence of a solid component in histopathological analysis to be associated with a poor prognosis of AdCC, regardless of its proportion in the specimen.

A meta-analysis conducted by Ju et al. [25] indicated that perineural invasion is strongly associated with poor overall survival and DFS. The neural tropism of AdCC and the capacity of neoplastic cells to migrate along nerve fibers are strong predictors of recurrence of AdCC [5]. According to Amit et al. [26], intraneural invasion is more strongly correlated with a poor prognosis than perineural invasion and is a reliable prognostic predictor of AdCC. Perineural invasion was associated with poor 10-year DSS (p = 0.025) in our study, corroborating the results of other studies.

Amit et al. [27] analyzed the role of surgical margins in 507 cases of head and neck AdCC in an international multicenter study. As observed in our study, the authors found a high rate of positive surgical margins (50% of the cases analyzed) and concluded that positive margins are predictors of poor survival in head and neck AdCC, while negative proximal margins (tumor-free margins < 5 mm) are associated with a favorable prognosis. The ability to achieve broad tumor-free margins depends on a range of factors, including location and size of the tumor, histopathological pattern and previous treatment. In many cases, surgery is limited by the proximity of vital structures. Studies demonstrated that patients with AdCC arising at sites close to the skull base (nasopharynx, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses) have a significantly higher risk of local recurrence [27, 28]. Although positive margins were associated with a poor 5- and 10-year prognosis in univariate analysis (p = 0.018 and p < 0.001, respectively), surgical margin status showed no independent prognostic value in multivariate analysis.

Like in the present study, surgical treatment combined with radiotherapy remains the most common therapeutic modality for the management of patients with AdCC [4, 17, 19]. Systemic therapy is generally reserved for palliative treatment. Many biomarkers are currently emerging as prognostic and predictive factors of targeted therapies. In this respect, C-kit, VEGF and Notch-1 are described as important molecular prognostic markers [29, 30]. Future studies that thoroughly evaluate possible therapeutic targets considering the molecular features of AdCC will pave the way for targeted therapies.

In conclusion, the present results confirm that clinical stage of the tumor, histopathological pattern and perineural invasion are important prognostic predictors in patients with AdCC. Other parameters such as surgical margins also exert a significant influence on clinical outcome. Considering the long-term aggressive behavior of AdCC, rigorous follow-up of patients is important to identify possible locoregional or distant recurrences. Detailed analysis of clinical–pathological parameters can assist professionals with treatment planning and prognostic prediction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Postgraduate Program in Oral Pathology of the UFRN and Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—CAPES. RAF and LBS are Research Productivity Fellows at National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing fnancial interests. There is no confict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.El-Naggar AK, Chan JK, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ. World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Silva LP, Serpa MS, Viveiros SK, Sena DAC, de Carvalho Pinho RF, de Abreu Guimarães LD, et al. Salivary gland tumors in a Brazilian population: a 20-year retrospective and multicentric study of 2292 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46(12):2227–2233. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh AS, Khawaja A, Puram SV, Srikanth P, Tjoa T, Lee H, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in parotid gland malignancies: a 10-year single center experience. Laryng Investig Otolaryngol. 2019;4(6):632–639. doi: 10.1002/lio2.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjørndal K, Krogdahl A, Therkildsen MH, Kristensen CA, Charabi B, Andersen E, et al. Salivary gland carcinoma in Denmark 1990e2005: a national study of incidence, site and histology. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) Oral Oncol. 2011;47(7):677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dantas AN, Morais EF, Macedo RA, Tinôco JM, Morais ML. Clinicopathological characteristics and perineural invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma: a systematic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81(3):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cordesmeyer R, Schliephake H, Kauffmann P, Tröltzsch M, Laskawi R, Ströbel P, et al. Clinical prognostic factors of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma: a single-center analysis of 61 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(11):1784–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girelli L, Locati L, Galeone C, Scanagatta P, Duranti L, Licitra L, et al. Lung metastasectomy in adenoid cystic cancer: is it worth it? Oral Oncol. 2017;65:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mays AC, Hanna EY, Ferrarotto R, Phan J, Bell D, Silver N, et al. Prognostic factors and survival in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sinonasal cavity. Head Neck. 2018;40(12):2596–2605. doi: 10.1002/hed.25335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg M, Tudor-Green B, Bisase B. Current thinking in the management of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57(8):716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2019.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang S, Patel PN, Kimple RJ, McCulloch TM. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(6):3045–3052. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins-Andrade B, Dos Santos Costa SF, Sant'ana MSP, Altemani A, Vargas PA, Fregnani ER, et al. Prognostic importance of the lymphovascular invasion in head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019;93:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang CY, Xia RH, Han J, Wang BS, Tian WD, Zhong LP, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: clinicopathologic analysis of 218 cases in a Chinese population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(3):368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang CF, Hsieh MY, Chen MK, Chou MC. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of head and neck: a retrospective clinical analysis of a single institution. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(4):831–837. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordesmeyer R, Kauffmann P, Laskawi R, Rau A, Bremmer F. The incidence of occult metastasis and the status of elective neck dissection in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma: a single center study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(6):516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosconi C, de Arruda JAA, de Farias ACR, Oliveira GAQ, de Paula HM, Fonseca FP, et al. Immune microenvironment and evasion mechanisms in adenoid cystic carcinomas of salivary glands. Oral Oncol. 2019;88:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atallah S, Casiraghi O, Fakhry N, Wassef M, Uro-Coste E, Espitalier F, et al. A prospective multicentre REFCOR study of 470 cases of head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma: epidemiology and prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2020;130:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amit M, Binenbaum Y, Sharma K, Ramer N, Ramer I, Agbetoba A, et al. Analysis of failure in patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. An international collaborative study. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):998–1004. doi: 10.1002/hed.23405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko JJ, Siever JE, Hao D, Simpson R, Lau HY. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of head and neck: clinical predictors of outcome from a Canadian centre. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(1):26–33. doi: 10.3747/co.23.2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takebayashi S, Shinohara S, Tamaki H, Tateya I, Kitamura M, Mizuta M, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: a retrospective multicenter study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138(1):73–79. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2017.1371329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Weert S, van der Waal I, Witte BI, Leemans CR, Bloemena E. Histopathological grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: analysis of currently used grading systems and proposal for a simplified grading scheme. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubal PM, Unsal AA, Chung SY, Patel AV, Park RC, Baredes S, et al. Population-based trends in outcomes in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the oral cavity. Am J Otolaryngol. 2016;37(5):398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perzin KH, Gullane P, Clairmont AC. Adenoid cystic carcinomas arising in salivary glands: a correlation of histologic features and clinical course. Cancer. 1978;42(1):265–282. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197807)42:1<265::AID-CNCR2820420141>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szanto PA, Luna MA, Tortoledo ME, White RA. Histologic grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands. Cancer. 1984;54(6):1062–1069. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840915)54:6<1062::AID-CNCR2820540622>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ju J, Li Y, Chai J, Ma C, Ni Q, Shen Z, et al. The role of perineural invasion on head and neck adenoid cystic carcinoma prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(6):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amit M, Binenbaum Y, Trejo-Leider L, Sharma K, Ramer N, Ramer I, et al. International collaborative validation of intraneural invasion as a prognostic marker in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2015;37(7):1038–1045. doi: 10.1002/hed.23710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amit M, Na'ara S, Trejo-Leider L, Ramer N, Burstein D, Yue M, et al. Defining the surgical margins of adenoid cystic carcinoma and their impact on outcome: an international collaborative study. Head Neck. 2017;39(5):1008–1014. doi: 10.1002/hed.24740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garden AS, Weber RS, Morrison WH, Ang KK, Peters LJ. The influence of positive margins and nerve invasion in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck treated with surgery and radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;32(3):619–626. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00122-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitani Y, Li J, Rao PH, Zhao YJ, Bell D, Lippman SM, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the MYB-NFIB gene fusion in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma: Incidence, variability, and clinicopathologic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(19):4722–4731. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sajed DP, Faquin WC, Carey C, Severson EA, Afrogheh HA, Johnson AC, et al. Diffuse staining for activated NOTCH1 correlates with NOTCH1 mutation status and is associated with worse outcome in adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(11):1473. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]