Abstract

Dermal filler injections are common cosmetic procedures and are growing in popularity. While frequently performed, dermal filler injections carry a risk of adverse events including vascular compromise and foreign body granulomas. Here, we discuss an unusual case of a patient with a history of dermal filler injections presenting with a parotid mass and an eyebrow mass requiring surgical resection. This case demonstrates the risk of delayed granuloma formation many years after dermal filler injection and highlights the importance of awareness and management of these potential long-term complications.

Keywords: Parotid mass, Dermal filler, Injectable, Complications

Introduction

Injection of dermal fillers are a common cosmetic procedure aimed at reducing the appearance of wrinkles in the face. Fillers have a long history in the United States, and a variety of substances have been approved for cosmetic use since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved collagen injections for correction of facial contour deficiencies in 1981 [1]. Temporary fillers approved by the FDA include collagen, hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxyapatite and poly-l-lactic acid. The only permanent dermal filler approved by the FDA is polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) [2]. Dermal fillers have become an increasingly common form of cosmetic rejuvenation, made popular because of their relatively low cost and minimal invasiveness compared with cosmetic surgery. For instance, over 2.6 million soft tissue fillers were injected in the United States in 2017 according to data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, a significant increase from the 1.7 million soft tissue fillers injected in 2010 [3, 4]. Dermal fillers are often performed by physicians such as dermatologists and plastic surgeons including oculoplastic and facial plastic surgeons. However, as the market continues to expand, many other healthcare providers including dentists, mid-level providers and aestheticians are now trained and equipped to inject dermal fillers.

While these procedures are generally safe, they are not without risk of complications. Immediate adverse events include vascular occlusion, necrosis, and blindness. Delayed adverse events include granuloma formation such as the case here [5]. Complication risks vary widely by the type of filler injected and the injection site. The reported incidence of specific adverse events varies from 0.09% for necrosis and abscess, to 1% for granuloma formation [5, 6]. One multicenter study found that the adverse event rate for dermal filler procedures was 0.74%, with lumps and nodules being the most common adverse event, though this study was limited to data only from board-certified dermatologists [7]. The increased use of such fillers demands an increased awareness of their potential complications from providers who perform the injections, as well as from providers who may be tasked with treating the long-term complications of dermal filler injections.

Case Description

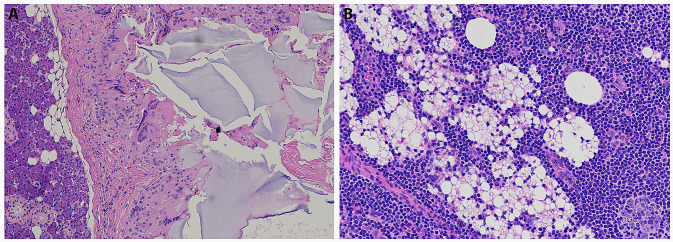

A 69-year old Caucasian female presented with a right parotid mass located at the angle of the mandible. MRI demonstrated a focal dilation of the right Stensen’s duct and a 2 mm nodule in the right superficial parotid suggestive for benign pleomorphic adenoma. (Fig. 1) On physical exam, the mass was palpable and approximately 0.5 cm. Subsequent fine needle aspiration demonstrated “cohesive groups of epithelioid cells and abundant chondroid matrix like material,” and could not rule out pleomorphic adenoma.

Fig. 1.

Axial view of T2-weighted images of MRI face that demonstrates high intensity of a small right parotid mass

The patient had a history of multiple dermal filler injections to the forehead performed many years prior to presentation by a licensed dermatologist. Other medical history included breast cancer, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and heart disease.

The patient underwent superficial parotidectomy with facial nerve preservation for the removal of the mass. The procedure was noted for difficulty in locating the small mass. Postoperatively, patient developed a sialocele, which was drained and subsequently resolved. Otherwise, she did not experience any additional complications of the parotidectomy.

Final pathology of the specimen showed epithelioid histiocytic and giant cell reaction of amorphous, non-polarizable foreign material (0.5 cm) involving periparotid soft tissue and one benign intraparotid lymph node with histiocytic reaction also consistent with a foreign body-type reaction. No neoplasm was identified on cytopathology assessment.

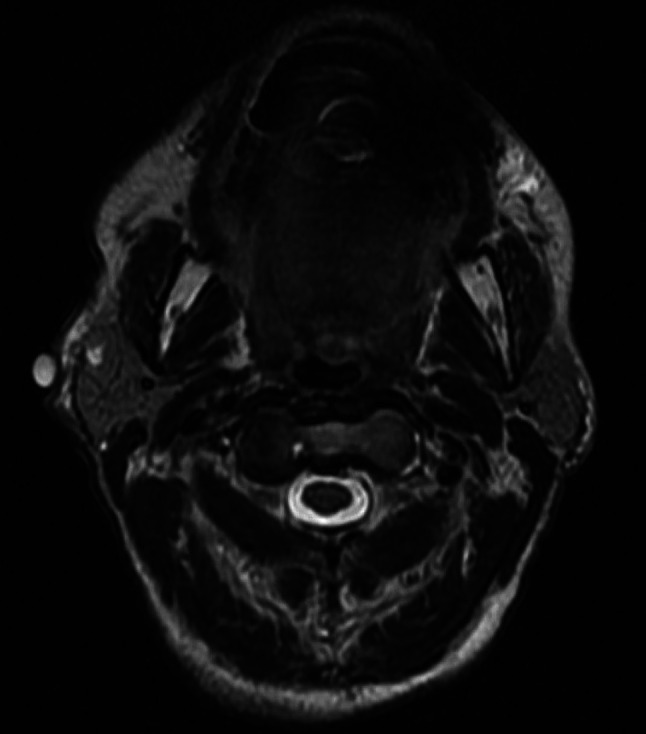

Pathology images demonstrated two distinct patterns of foreign bodies, suggesting this patient may have in fact received various forms of soft tissue filler injections, or a combination of substances. The images of the periparotid soft tissue (Fig. 2a) contained amorphous, slightly basophilic foreign bodies on H&E staining, suggestive of hyaluronic acid or polyacrylamide gel [8].

Fig. 2.

a Histological image (H&E stain) of the parotid mass demonstrating evidence of foreign body reaction. b Histological image (H&E) of intraparotid lymph node demonstrating foreign body substance and reaction

In the pathology image of the involved intraparotid lymph node (Fig. 2b), there are many small, round, nonstaining spaces in the tissue, suggestive of silicone, which is another permanent injectable and one that is more likely to present with delayed adverse reactions [8]. However, the original filler material could not be identified on histological review.

Two months after her initial parotidectomy, the patient presented again with a 1–2 cm, firm, mobile, non-tender mass over her right eyebrow. The mass was removed and pathological examination revealed a foreign body granuloma secondary to injection of a foreign substance. She recovered from this procedure with no issues.

Discussion

We present a rare case of a delayed adverse event attributable to dermal filler injection. Foreign body granuloma incidence ranges from 0.02 to 1% in recipients of dermal filler injections and have been reported to occur in a wide variety of filler types [6, 9]. Although the patient did not provide information on the type of filler used, the lapse of many years between filler injections and granuloma presentation suggests the use of more permanent type of filler, such as PMMA or polyacrylamide gel. It is possible for patients who present with extremely delayed reactions to not remember the type of filler used, which may delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment [10]. The pathogenesis of such foreign body granulomas is still unclear, but may be triggered by a systemic infection or a pharmacologic stimulus [6].

This case contributes to a growing recognition of the long-term risks of injectable filler use. As the popularity of dermal fillers grows, patients and providers must be aware of the risk of long-term complications, which may require surgical intervention in some cases [10, 11]. A recent analysis found that two-thirds of litigations concerning dermal fillers noted an alleged lack of informed consent, demonstrating the importance of reviewing risks with patients from both an ethical and legal perspective [12]. Additionally, this patient recalls her filler injections were performed by a licensed dermatologist. In recent years, as demand for dermal fillers has grown, there has been an increase in variably trained providers offering dermal filler injections [5, 12]. Risk of complication exists even with experienced providers, and that risk only increases when the injection is performed by providers with less training and poorer technique [5, 13]. In all situations, it is vital that patients understand the potential risks of what is often a cosmetic procedure, and that physicians recognize and appropriately treat both the short-term and long-term adverse events associated with this increasingly popular procedure.

The presentation of the granuloma in the patient’s parotid and eyebrow regions suggests either a delayed reaction or a migration of dermal filler material that may have initially been injected to the forehead or cheeks. It is possible that filler material was injected in these areas purposefully to provide volume or define the mandibular angle. With time, natural atrophy and jowling of facial structures may have accentuated these injection materials. Presentation of filler migration from original injection sites have been reported previously. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested including poor injection technique, excessive injection volume, muscle activity, gravity, and lymphatic spread [13–15]. The migration of this patient’s filler material to her parotid and eyebrow areas suggest that the filler may have migrated over years as a result of gravity and muscle activity. If the foreign material in the patient’s lymph node is silicone, this may suggest that injected silicone can migrate through the lymphatic system, perhaps through interaction and transport via phagocytes [13, 16]. Additionally, the FDA specifically warns against using injectable silicone for body contouring and lists silicone as an unapproved dermal filler, in part due to its potential to migrate through blood vessels [17, 18].

This case highlights a unique presentation of a delayed complication from dermal fillers. The patient underwent two surgeries as a result of this complication. Her superficial parotidectomy was complicated by sialocele formation. Although she did not experience major complications, the patient did have to take on the potential risk for facial nerve damage during parotidectomy as well as the stress and cost of undergoing additional workup for abnormal facial lesions. Providers must recognize that dermal filler complications may occur distant from the site of injection and discuss this potential with patients as a part of the informed consent process. Future research should focus on categorizing the types and rates of all potential adverse events related to dermal fillers.

Conclusion

There are known complications of dermal fillers but few present as delayed adverse events years after initial injections. We present a patient who underwent two excisions of abnormal facial lesions that was discovered to be foreign body reaction to filler material. She underwent superficial parotidectomy that was complicated by sialocele formation that required subsequent drainage as an outpatient. This case demonstrates the importance of explaining potential long-term complications of dermal filler injections as a part of the informed consent process.

Funding

The authors have no funding, financial relationships.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Klein AW, Elson ML. The history of substances for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(12):1096–1105. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballin AC, Brandt FS, Cazzaniga A. Dermal fillers: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16(4):271–283. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surgeons ASoP. Plastic surgery statistics report. 2017.

- 4.Surgeons ASoP. Plastic surgery statistics full report. 2010.

- 5.Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse reactions to injectable fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016;32(5):532–555. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N, Wolters M, Eisemann-Klein M, Zimmermann U, Duffy DM. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 1. Possible causes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(6):1842–1863. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818236d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam M, Kakar R, Nodzenski M, et al. Multicenter prospective cohort study of the incidence of adverse events associated with cosmetic dermatologic procedures: lasers, energy devices, and injectable neurotoxins and fillers. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(3):271–277. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haneke E. Adverse effects of fillers and their histopathology. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(6):599–614. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1396755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers, part I. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(4):561–575. doi: 10.1177/1090820X13484492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe NJ, Maxwell CA, Patnaik R. Adverse reactions to dermal fillers: review. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1616–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, Zimmermann US, Kutzner H, Cerroni L. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayess HM, Svider PF, Hanba C, et al. A cross-sectional analysis of adverse events and litigation for injectable fillers. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(3):207–214. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2017.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jordan DR, Stoica B. Filler migration. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(4):257–262. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chae SY, Lee KC, Jang YH, Lee SJ, Kim DW, Lee WJ. A case of the migration of hyaluronic acid filler from nose to forehead occurring as two sequential soft lumps. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(5):645–647. doi: 10.5021/ad.2016.28.5.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shahrabi-Farahani S, Lerman MA, Noonan V, Kabani S, Woo SB. Granulomatous foreign body reaction to dermal cosmetic fillers with intraoral migration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117(1):105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki KAM, Kawana S, Hyakusoku H, Miyazawa S. Metastatic silicone granuloma: lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei–like facial nodules and sicca complex in a silicone breast implant recipient. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(4):537–538. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Administration USFD. FDA warns against use of injectable silicone for body contouring and enhancement: FDA safety communication. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safety-communications/fda-warns-against-use-injectable-silicone-body-contouring-and-enhancement-fda-safety-communication.

- 18.Administration USFD. Dermal fillers approved by the center for devices and radiological health. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/cosmetic-devices/dermal-fillers-approved-center-devices-and-radiological-health-0#unapproved.