Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gastric cancers can be categorized into diffuse- and intestinal-type cancers based on the Lauren histopathological classification. These two subtypes show distinct differences in metastasis frequency, treatment application, and prognosis. Therefore, accurately assessing the Lauren classification before treatment is crucial. However, studies on the gastritis endoscopy-based Kyoto classification have recently shown that endoscopic diagnosis has improved.

AIM

To investigate patient characteristics including endoscopic gastritis associated with diffuse- and intestinal-type gastric cancers in Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected patients.

METHODS

Patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic were enrolled. The Kyoto classification included atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, nodularity, and diffuse redness. The effects of age, sex, and Kyoto classification score on gastric cancer according to the Lauren classification were analyzed. We developed the Lauren predictive background score based on the coefficients of a logistic regression model using variables independently associated with the Lauren classification. Area under the receiver operative characteristic curve and diagnostic accuracy of this score were examined.

RESULTS

A total of 499 H. pylori-infected patients (49.6% males; average age: 54.9 years) were enrolled; 132 patients with gastric cancer (39 diffuse- and 93 intestinal-type cancers) and 367 cancer-free controls were eligible. Gastric cancer was independently associated with age ≥ 65 years, high atrophy score, high intestinal metaplasia score, and low nodularity score when compared to the control. Factors independently associated with intestinal-type cancer were age ≥ 65 years (coefficient: 1.98), male sex (coefficient: 1.02), high intestinal metaplasia score (coefficient: 0.68), and low enlarged folds score (coefficient: -1.31) when compared to diffuse-type cancer. The Lauren predictive background score was defined as the sum of +2 (age ≥ 65 years), +1 (male sex), +1 (endoscopic intestinal metaplasia), and -1 (endoscopic enlarged folds) points. Area under the receiver operative characteristic curve of the Lauren predictive background score was 0.828 for predicting intestinal-type cancer. With a cut-off value of +2, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the Lauren predictive background score were 81.7%, 71.8%, and 78.8%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Patient backgrounds, such as age, sex, endoscopic intestinal metaplasia, and endoscopic enlarged folds are useful for predicting the Lauren type of gastric cancer.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Lauren classification, Endoscopy, Pathology, Gastritis, Kyoto classification

Core Tip: Accurately assessing the Lauren classification before the treatment of gastric cancer is crucial. Factors independently associated with intestinal-type cancer were age ≥ 65 years, male sex, high endoscopic intestinal metaplasia score, and low endoscopic enlarged folds score when compared to diffuse-type cancer. The Lauren predictive background score was defined as the sum of +2 (age ≥ 65 years), +1 (male), +1 (intestinal metaplasia), and -1 (enlarged folds) points. Area under the curve of the Lauren predictive background score was 0.828 (cut-off: +2) for predicting intestinal-type cancer. Age, sex, intestinal metaplasia, and enlarged folds are useful for predicting tumor type.

INTRODUCTION

The International Agency for Research on Cancer reported in GLOBOCAN 2018 that stomach cancer was the third leading cause of mortality worldwide[1]. Gastric cancers are epidemiologically crucial and can be categorized into two types based on the Lauren histopathological classification: diffuse and intestinal-types[2]. Intestinal-type cancers are associated with a Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-induced chronic inflammatory process, known as the Correa pathway, which includes atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer[3], whereas diffuse-type gastric cancers directly undergo a highly active inflammation-based carcinogenesis without having to pass through the Correa pathway[4,5]. The two histological subtypes of gastric tumors proposed by Lauren exhibit several distinct clinical and molecular characteristics[6-8]. Depending on the Lauren type, the frequency of lymph node metastasis[2,9,10] and peritoneal metastasis[11,12], application of endoscopic mucosal dissection[13,14], recommended surgical margin[15], response to chemotherapy[16], and prognosis[2,16,17] differ. The Lauren classification is diagnosed by pathology; however, it would be useful if subtypes could be endoscopically predicted.

In recent years, advancement in endoscopy has enabled diagnosis that is highly consistent with histology[18,19]. In 2013, the endoscopy-based Kyoto classification of gastritis was advocated by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society with the aim of unifying the endoscopic diagnosis of gastritis in clinical practice and match it with the pathological diagnosis of gastritis[20]. The Kyoto classification adopted and scored atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, nodularity, diffuse redness, and the regular arrangement of collecting venules (RAC) as endoscopic findings of gastritis. Among them, the Kyoto score, which is the sum of the scores of these factors, has been vigorously reported to be associated with gastric cancer[21,22], gastric cancer risk[20,23], and H. pylori infections[24]. Evaluating the risk of gastric cancer on the basis of endoscopic findings is an important alternative to biopsy.

Since there are few reports regarding the relationship between the Lauren classification and endoscopic findings based on the Kyoto classification[21,22], we investigated the background patient characteristics and endoscopic gastritis of patients with diffuse- and intestinal-type gastric cancers, focusing on H. pylori infected patients. Based on these outcomes, a score was created to predict the Lauren classification, and its accuracy was examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and oversight

We conducted a retrospective case-control study at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, which is an outpatient endoscopy-specialized clinic located in Tokyo, an urban area in Japan. This study was approved by the certificated review board of the Hattori Clinic on September 4, 2020 (approval No. S2009-U04, registration number UMIN000018541). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study received no financial support.

Study population

Eligibility criteria included patients with gastric cancer and an H. pylori infection who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic from September 2008 to February 2020. We excluded patients who did not have H. pylori infection, patients in whom H. pylori was successfully eradicated, and those whose H. pylori status was unavailable. Patients with gastric cancer and past gastrectomy were also excluded. As control group, patients with H. pylori-positive gastritis and without gastric cancer were enrolled. This criterion included patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and initial assessments for an H. pylori infection from December 2013 to March 2016 and from January 2018 to February 2019.

Diagnosis of Lauren classification and H. pylori infection

The Lauren classification was diagnosed from resected specimens or, if unresectable, biopsy specimens.

An H. pylori infection was diagnosed using pathology (hematoxylin and eosin staining) or the urea breath test.

Endoscopic gastritis based on the Kyoto classification

The Kyoto score for endoscopic gastritis, which ranges from 0 to 8, is based on the total scores of the following five endoscopic findings: atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, nodularity, and diffuse redness. A high score represents an increased risk of gastric cancer[20-23] and H. pylori infection[24].

Endoscopic atrophy was classified based on the extent of mucosal atrophy (the Kimura Takemoto classification)[26]. Non-atrophy and C1 atrophy were scored as atrophy score 0, C2, and C3 atrophies as atrophy score 1, and O1 to O3 atrophies as atrophy score 2.

Endoscopically, intestinal metaplasia typically appears as grayish-white and slightly elevated plaques surrounded by mixed patchy pink and pale areas of the mucosa, forming an irregular uneven surface. A villous appearance, whitish mucosa, and rough mucosal surface are useful indicators for the endoscopic diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia. Intestinal metaplasia score 0 was defined as the absence of intestinal metaplasia, score 1 as the presence of intestinal metaplasia within the antrum, and score 2 as intestinal metaplasia extending into the corpus. The intestinal metaplasia score was calculated based on the diagnosis of metaplasia using white-light imaging.

An enlarged fold is defined as ≥ 5 mm width that is not flattened or is only partially flattened by stomach insufflation. The absence and presence of enlarged folds were scored as enlarged fold scores of 0 and 1, respectively.

Nodularity is a condition in which a miliary pattern similar to “goosebumps” is mainly located in the antrum. The absence and presence of nodularity were scored as nodularity scores of 0 and 1, respectively.

Diffuse redness refers to uniformly reddish mucosa with continuous expansion located in the non-atrophic mucosa, mainly in the corpus. The RAC is a condition in which collecting venules are arranged in the corpus. From a distance, the venules look like numerous dots; however, up close, the venules appear like a regular pattern of starfish-like shapes. The absence of diffuse redness, presence of mild diffuse redness or diffuse redness with RAC, and severe diffuse redness or diffuse redness without RAC were scored as diffuse redness scores of 0, 1, and 2, respectively.

Data collection and outcomes

We obtained data for cancer and participants background information from the endoscopic database of the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic from September 2008 to February 2020. Two expert endoscopists reviewed all images and scored them according to the Kyoto classification.

Clinical data of this study consisted of variables including gastric cancer type according to the Lauren classification, age, sex, and endoscopic gastritis score based on the Kyoto classification (Kyoto score, atrophy score, intestinal metaplasia score, enlarged folds score, nodularity score, and diffuse redness score).

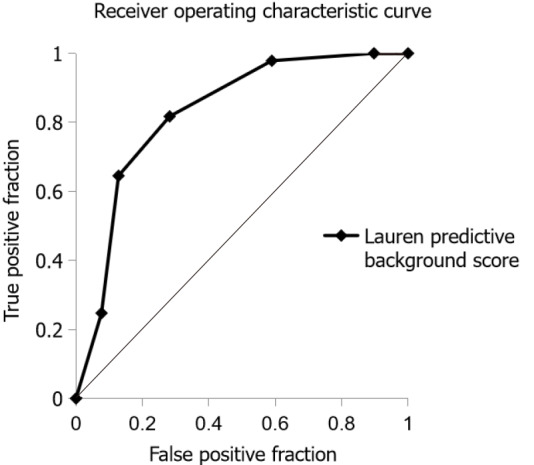

The main outcome of this study was the differences in patient backgrounds and the endoscopic gastritis between patients with diffuse- and intestinal-type gastric cancers. To predict the Lauren type of cancer, this study developed a Lauren predictive background score using variables associated with the Lauren classification. We assessed the discrimination of the Lauren predictive background score using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the corresponding area under the ROC curve (AUC), and the diagnostic accuracy of predicting the Lauren type of tumor.

We also compared H. pylori-infected patients with cancer (whole, diffuse-, and intestinal-type cancers, respectively) and cancer-free H. pylori-infected controls.

Statistical analyses

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted using a binomial logistic regression analysis. The multivariate analysis included age, sex, and each score of the Kyoto classification, excluding the Kyoto score. Age was categorized based on the average number of patients with gastric cancer. A multivariate analysis was conducted, using a backward stepwise logistic regression, for variables with P values < 0.1; these values were determined by a univariate analysis. Regarding missing data, we used complete case analysis.

We developed the Lauren predictive background score based on the coefficients of a logistic regression model, using variables with P values < 0.05 in a multivariate analysis. The AUC for predicting intestinal-type cancer and the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the Lauren predictive background score were measured. The optimal cut-off value of the ROC curve was calculated using the Youden index.

A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Ekuseru-Toukei 2015 (Social Survey Research Information company, Limited, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

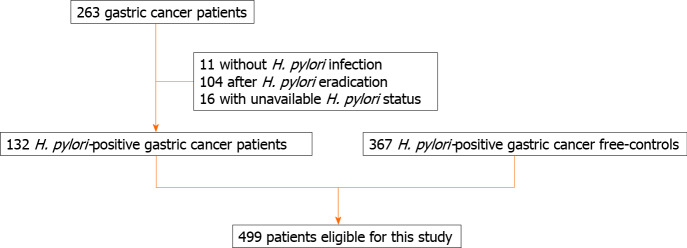

A total of 132 patients with H. pylori-positive gastric cancers (39 diffuse- and 93 intestinal-type, 105 early, and 27 advanced cancers) were included; 11 patients were excluded as they did not have an H. pylori infection, 104 due to successful eradication, and 16 due to an unavailable H. pylori status. The control group comprised 367 patients with H. pylori-positive gastritis (gastric cancer free controls). A total of 499 patients were enrolled in this study. We show patient flowchart in Figure 1. The mean age in this study was 54.9 ± 14.1 (range: 23-89) years, and 49.6% of patients were male; the Kyoto score was 4.93 ± 1.58, (atrophy: 1.53 ± 0.61; intestinal metaplasia: 0.83 ± 0.92; enlarged folds: 0.42 ± 0.49; nodularity: 0.33 ± 0.47; and diffuse redness: 1.83 ± 0.48).

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

H. pylori-positive gastritis with vs without gastric cancer

Univariate analysis showed that patients with H. pylori-infected cancer patients were older (66.4 vs 50.9 years) and had a higher Kyoto score (5.63 vs 4.69) than H. pylori-infected non-cancer patients. Among the scores of the items of the Kyoto classification, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia scores for gastric cancer were higher than those for cancer-free gastritis; however, nodularity scores for gastric cancer were lower than those for cancer-free gastritis. There was no significant difference in the enlarged folds and diffuse redness scores. Based on the results of a multivariate analysis, H. pylori-infected gastric cancer was independently associated with an age of 65 years or more [odds ratio (OR): 4.01], a high atrophy score (OR: 2.80), high intestinal metaplasia score (OR: 1.57), and a low nodularity score (OR: 0.51, Table 1).

Table 1.

Endoscopic gastritis based on Kyoto classification of Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with vs without gastric cancer

|

|

Gastric cancer (+)

|

Cancer (-)

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|

|

|

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| n | 132 | 367 | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 66.4 (12.4) | 50.9 (12.4) | 1.099 | 1.078-1.120 | < 0.001 | |||

| Age ≥ 65 yr, % | 60.6 | 15.3 | 8.544 | 5.446-13.405 | < 0.001 | 4.010 | 2.436-6.603 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex, % | 55.3 | 47.7 | 1.357 | 0.910-2.024 | 0.134 | |||

| Atrophy score, mean (SD) | 1.871 (0.336) | 1.411 (0.642) | 6.173 | 3.635-10.486 | < 0.001 | 2.800 | 1.583-4.954 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia score, mean (SD) | 1.402 (0.809) | 0.624 (0.878) | 2.570 | 2.031-3.253 | < 0.001 | 1.567 | 1.188-2.067 | 0.001 |

| Enlarged folds score, mean (SD) | 0.364 (0.483) | 0.441 (0.497) | 0.723 | 0.480-1.090 | 0.121 | |||

| Nodularity score, mean (SD) | 0.152 (0.360) | 0.387 (0.488) | 0.283 | 0.168-0.476 | < 0.001 | 0.508 | 0.282-0.913 | 0.024 |

| Diffuse redness score, mean (SD) | 1.841 (0.507) | 1.823 (0.466) | 1.085 | 0.706-1.667 | 0.709 | |||

| Kyoto score, mean (SD) | 5.629 (1.149) | 4.687 (1.637) | 1.568 | 1.342-1.831 | < 0.001 | |||

P value was calculated using the binomial logistic regression analysis. CI: Confidence interval; SD: Standard deviation.

H. pylori-infected gastritis with diffuse-type gastric cancer vs without gastric cancer

On comparing H. pylori-infected patients with diffuse-type cancer and those without gastric cancer (gastric cancer-free controls), a univariate analysis showed that patients with diffuse-type cancer were older (58.0 vs 50.9 years) and had a higher Kyoto score (5.33 vs 4.69), higher atrophy score, and higher intestinal metaplasia score than gastric cancer-free patients. In a multivariate analysis, a high atrophy score was independently associated with diffuse-type gastric cancer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Endoscopic gastritis based on Kyoto classification of Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with diffuse-type gastric cancer vs without gastric cancer

|

|

Diffuse-type cancer (+)

|

Cancer (-)

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|

|

|

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| n | 39 | 367 | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 58.00 (13.00) | 50.88 (12.41) | 1.044 | 1.018-1.072 | 0.001 | |||

| Age ≥ 65 yr, % | 28.2 | 15.3 | 2.182 | 1.027-4.634 | 0.042 | 1.434 | 0.633-3.246 | 0.388 |

| Male sex, % | 38.5 | 47.7 | 0.686 | 0.348-1.349 | 0.275 | |||

| Atrophy score, mean (SD) | 1.692 (0.468) | 1.411 (0.642) | 2.327 | 1.223-4.428 | 0.010 | 2.327 | 1.223-4.428 | 0.010 |

| Intestinal metaplasia score, mean (SD) | 0.974 (0.903) | 0.624 (0.878) | 1.516 | 1.065-2.158 | 0.021 | 1.313 | 0.905-1.906 | 0.152 |

| Enlarged folds score, mean (SD) | 0.564 (0.502) | 0.441 (0.497) | 1.638 | 0.842-3.186 | 0.146 | |||

| Nodularity score, mean (SD) | 0.282 (0.456) | 0.387 (0.488) | 0.622 | 0.300-1.290 | 0.202 | |||

| Diffuse redness score, mean (SD) | 1.821 (0.556) | 1.823 (0.466) | 0.990 | 0.495-1.978 | 0.976 | |||

| Kyoto score, mean (SD) | 5.333 (1.402) | 4.687 (1.637) | 1.306 | 1.044-1.632 | 0.019 | |||

P value was calculated using the binomial logistic regression analysis. CI: Confidence interval; SD: Standard deviation.

H. pylori-infected gastritis with intestinal-type gastric cancer vs without gastric cancer

H. pylori-infected intestinal-type gastric cancer and H. pylori-infected non-cancer gastritis were compared. Univariate analysis showed that H. pylori-infected patients with intestinal-type gastric cancer were older (69.9 vs 50.9 years), comprised more of males (62.4% vs 47.7%), and had a higher Kyoto score (5.75 vs 4.69), higher atrophy score, higher intestinal metaplasia score, lower enlarged folds score, and lower nodularity score than those with non-cancer gastritis. Similar results were obtained in multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Endoscopic gastritis based on Kyoto classification of Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with intestinal-type gastric cancer vs without gastric cancer

|

|

Intestinal-type cancer (+)

|

Cancer (-)

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||

|

|

|

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| n | 93 | 367 | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 69.86 (10.29) | 50.88 (12.41) | 1.138 | 1.107-1.169 | < 0.001 | |||

| Age ≥ 65 yr, % | 74.2 | 15.3 | 15.967 | 9.261-27.527 | < 0.001 | 6.220 | 3.394-11.400 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex, % | 62.4 | 47.7 | 1.818 | 1.140-2.900 | 0.012 | 1.794 | 0.955-3.372 | 0.069 |

| Atrophy score, mean (SD) | 1.946 (0.227) | 1.411 (0.642) | 15.312 | 6.147-38.144 | < 0.001 | 6.167 | 2.321-16.382 | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal metaplasia score, mean (SD) | 1.581 (0.697) | 0.624 (0.878) | 3.368 | 2.499-4.539 | < 0.001 | 1.683 | 1.166-2.430 | 0.005 |

| Enlarged folds score, mean (SD) | 0.280 (0.451) | 0.441 (0.497) | 0.491 | 0.299-0.808 | 0.005 | 0.453 | 0.237-0.867 | 0.017 |

| Nodularity score, mean (SD) | 0.097 (0.297) | 0.387 (0.488) | 0.170 | 0.083-0.348 | < 0.001 | 0.323 | 0.141-0.742 | 0.008 |

| Diffuse redness score, mean (SD) | 1.849 (0.488) | 1.823 (0.466) | 1.135 | 0.681-1.891 | 0.626 | |||

| Kyoto score, mean (SD) | 5.753 (1.007) | 4.687 (1.637) | 1.696 | 1.407-2.004 | < 0.001 | |||

P value was calculated using the binomial logistic regression analysis. CI: Confidence interval; SD: Standard deviation.

H. pylori-infected gastritis with diffuse- vs intestinal-type gastric cancer

Table 4 shows a comparison of endoscopic background gastritis between H. pylori-infected patients with diffuse- and intestinal-type cancers. Univariate analysis showed that patients with intestinal-type cancer were older (69.9 vs 58.0 years), comprised more of males (61.5% vs 37.6%), had a higher atrophy score (1.95 vs 1.69), higher intestinal metaplasia score (1.58 vs 0.97), lower enlarged folds score (0.28 vs 0.56), and lower nodularity score (0.10 vs 0.28). There was no significant difference in the Kyoto and diffuse redness scores. In a multivariate analysis, factors independently associated with intestinal-type cancer were an age of 65 years or more (coefficient: 1.98; OR: 7.26), male sex (coefficient: 1.02; OR: 2.78), high intestinal metaplasia score (coefficient: 0.68; OR: 1.97), and low enlarged folds score (coefficient: -1.31; OR: 0.27).

Table 4.

Endoscopic gastritis based on Kyoto classification of Helicobacter pylori-infected patients with diffuse- vs intestinal-type gastric cancer

|

|

Diffuse-type

|

Intestinal-type

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

Coefficient

|

95%CI

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P

value

|

| n | 39 | 93 | ||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 58.00 (13.00) | 69.86 (10.29) | 1.091 | 1.051-1.132 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Age ≥ 65 yr, % | 28.2 | 74.2 | 7.318 | 3.166-16.917 | < 0.001 | 1.983 | 1.045, 2.921 | 7.263 | 2.843-18.553 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex, % | 38.5 | 62.4 | 2.651 | 1.228-5.724 | 0.013 | 1.021 | 0.069, 1.973 | 2.776 | 1.071-7.193 | 0.036 |

| Atrophy score, mean (SD) | 1.692 (0.468) | 1.946 (0.227) | 7.822 | 2.530-24.188 | < 0.001 | 0.727 | -0.927, 2.381 | 2.069 | 0.396-10.816 | 0.389 |

| Intestinal metaplasia score, mean (SD) | 0.974 (0.903) | 1.581 (0.697) | 2.473 | 1.544-3.959 | < 0.001 | 0.678 | 0.128, 1.228 | 1.970 | 1.136-3.413 | 0.016 |

| Enlarged folds score, mean (SD) | 0.564 (0.502) | 0.280 (0.451) | 0.300 | 0.138-0.653 | 0.002 | -1.308 | -2.261, -0.356 | 0.270 | 0.104-0.701 | 0.007 |

| Nodularity score, mean (SD) | 0.282 (0.456) | 0.097 (0.297) | 0.273 | 0.102-0.726 | 0.009 | -0.237 | -1.621, 1.147 | 0.789 | 0.198-3.149 | 0.737 |

| Diffuse redness score, mean (SD) | 1.821 (0.556) | 1.849 (0.488) | 1.116 | 0.545-2.288 | 0.764 | |||||

| Kyoto score, mean (SD) | 5.333 (1.402) | 5.753 (1.007) | 1.355 | 0.987-1.860 | 0.060 | |||||

P value was calculated using the binomial logistic regression analysis. CI: Confidence interval; SD: Standard deviation.

Based on the coefficients of a multivariate analysis, the equation for the scoring system was calculated based on an assumption that patients receive +2 points if they were aged 65 years or more, +1 point if they were male, +1 point if they had intestinal metaplasia, and -1 point if they had enlarged folds. We defined the Lauren predictive background score as the sum of these points, ranging from -1 to +4.

The ROC curve based on the Lauren predictive background score in 132 patients with diffuse- or intestinal-type cancer is shown in Figure 2. AUC of the Lauren predictive background score for predicting intestinal-type cancer was 0.828 (95% confidence interval: 0.744-0.912). The optimal cut-off value of the Lauren predictive background score for correlation with intestinal-type gastric cancer was +2, based on the Youden index. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the Lauren predictive background score were 81.7%, 71.8%, and 78.8%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for predicting intestinal-type gastric cancer. Receiver operating characteristics curve was based on the Lauren predictive background score in 132 patients with diffuse- or intestinal-type gastric cancer according to Lauren classification. The Lauren predictive background score was defined as a sum of the following points: +2 points for an age of 65 years or older, +1 point for male sex, +1 point for endoscopic intestinal metaplasia, and -1 point for endoscopic enlarged folds.

DISCUSSION

This study showed that old age, male sex, the presence of endoscopic intestinal metaplasia, and the absence of endoscopic enlarged folds were independently associated with intestinal-type gastric cancer compared to diffuse-type cancer among H. pylori-infected patients. The Lauren predictive background score created based on these variables was good, with AUC of 0.828, sensitivity of 81.7%, and accuracy of 78.8%. It is well known that old age, male sex[2,27], and endoscopic intestinal metaplasia[28] are indicators of intestinal-type cancers and that endoscopic enlarged folds[5,29] are characteristics of diffuse-type tumors. The strength of this study is that independent variables related to cancer type were investigated using the currently vigorously studied endoscopic gastritis evaluation method (Kyoto classification), and Lauren predictive background score was newly created using these variables; moreover, the score was accurate. Predicting cancer types without a biopsy may lead to faster treatment choices. A pathological diagnosis before endoscopic resection, surgery, or chemotherapy is vital to determine the line of treatment of lesions[13-16]. However, cases in which there are differences between the histological diagnoses of biopsy and resected specimens amount to 20%–30% of all cases[30-32]. Biopsy results are supported when the Lauren predictive background score is consistent with the biopsy diagnosis; however, the treatment should be carefully selected when discrepancies are observed. Furthermore, some endoscopic features of cancer are indicated by the Lauren classification. For example, diffuse-type cancers are frequently located in the proximal stomach[33]. The endoscopic gross appearance of an elevated-type cancer predominantly indicated intestinal-type cancer, whereas flat and depressed types of cancers indicated difuse-type cancer[34,35]. In the early stages of gastric cancer, intestinal-type cancer is usually reddish, whereas diffuse-type cancer is pale. While magnifying with narrow-band imaging, a well-demarcated area[36] and a white opaque substance[37] serve as an indicator of intestinal-type cancer, an ill-defined area[36] and a high proportion of the area with an absent microsurface pattern[38] are specific markers for diffuse-type cancer. In contrast, our study is unique in predicting the Lauren classification from background information rather than tumor information. In the future, a combination of both background and tumor information may allow for more accurate predictions, and a diagnosis by artificial intelligence may help.

We previously showed that corpus-predominant gastritis (5.96) has a higher Kyoto score than pangastritis (5.21)[20]. Corpus-predominant gastritis and pangastritis are risk factors for intestinal- and diffuse-type cancers, respectively[39], and a similar tendency was observed in this study.

Next, this study demonstrated that the Kyoto score of gastric cancer patients was higher than that of cancer-free patients among H. pylori-infected participants, regardless of whether the cancer was diffuse- or intestinal-type. This result is concordant with that of a previous report by Sugimoto et al[21]. While examining each item of the Kyoto classification, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia showed a positive association with gastric cancer; however, nodularity was negatively correlated with gastric cancer. This tendency is also the same as that reported in a previous study[21]. Nodularity has been reported as a risk factor for stomach cancer in young patients[40]; however, our observation might indicate a negative association since it covers all ages. When we previously investigated the association of the ABC classification, which consisted of a combination of serum H. pylori antibody and pepsinogen, with endoscopic gastritis, the simplified Kyoto score using only atrophy and intestinal metaplasia scores was more dramatically related to the ABC classification[27]. Combined with the results of this study, we suggest that nodularity and diffuse redness scores be not included in the gastric cancer risk score. Particularly, enlarged folds scores should be excluded from the risk score for intestinal-type cancer. However, further verifications are required for this matter.

This study has some limitations. The subjects of our study were limited to H. pylori-infected patients. Gastric cancer is detected even after H. pylori eradication[41]. Take et al[42] described an increased incidence of diffuse-type cancer more than 10 years after H. pylori eradication. Studying subjects after H. pylori eradication or H. pylori-uninfected subjects in the future is warranted. The gastric cancer-free control group in this study was extracted from a shorter period than the gastric cancer group. In the future, comparisons between the endoscopic background diagnosis of patients with gastric cancer (especially according to the Lauren classification) and that of non-cancer controls during the same period is desired. In addition, further investigations using prospective study designs are needed to evaluate the accuracy of the Lauren predictive background score. The sample size for that study would be 26 (8 patients with diffuse type cancer, and 19 patients with intestinal type cancer).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, patient backgrounds, such as age, sex, endoscopic intestinal metaplasia, and endoscopic enlarged folds are useful for predicting tumor type.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The accurate diagnosis of gastric cancer using the Lauren classification is crucial.

Research motivation

The relationship between the Lauren classification and endoscopic findings based on the Kyoto classification is not clear.

Research objectives

To investigate the background patient characteristics and endoscopic gastritis of patients with diffuse- and intestinal-type gastric cancers, focusing on Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected patients.

Research methods

This study included participants who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy at the Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic. The endoscopy-based Kyoto classification of gastritis consisted of atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, enlarged folds, nodularity, and diffuse redness. The effects of age, sex, and Kyoto classification score on gastric cancer according to the Lauren classification were analyzed.

Research results

A total of 499 H. pylori-infected patients (49.6% males; average age, 54.9 years) were enrolled. A total of 132 patients with gastric cancer (39 diffuse- and 93 intestinal-type) and 367 cancer-free controls were eligible. Gastric cancer was independently associated with age ≥ 65 years, high atrophy score, high intestinal metaplasia score, and low nodularity score when compared to the control. Factors independently associated with intestinal-type cancer were age ≥ 65 years, male sex, high intestinal metaplasia score, and low enlarged folds score when compared to diffuse-type cancer. The Lauren predictive background score was defined as the sum of the following points: +2 points for an age of ≥ 65 years, +1 point for male sex, +1 point for intestinal metaplasia, and -1 point for enlarged folds. The area under the curve of the Lauren predictive background score was 0.828 for predicting intestinal-type tumors. With a cut-off of +2, the sensitivity and specificity of the Lauren predictive background score were 81.7% and 71.8%, respectively.

Research conclusions

Patient backgrounds such as age, sex, endoscopic intestinal metaplasia, and endoscopic enlarged folds are useful for predicting tumor type.

Research perspectives

Studying subjects after H. pylori eradication or H. pylori-uninfected subjects in the future is warranted. Furthermore, comparisons between the endoscopic background diagnosis of patients with gastric cancer (especially according to Lauren classification) and that of non-cancer controls is desired.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Certificated Review Board, Hattori Clinic on September 4th, 2020 (approval no. S2009-U04, registration no. UMIN000018541).

Informed consent statement: Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. For full disclosure, the details of the study are published on the home page of Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All other authors have nothing to disclose.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: January 13, 2021

First decision: February 10, 2021

Article in press: April 14, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yu CH S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

Contributor Information

Osamu Toyoshima, Department of Gastroenterology, Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, Tokyo 157-0066, Japan. t@ichou.com.

Toshihiro Nishizawa, Department of Gastroenterology, Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, Tokyo 157-0066, Japan; Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, International University of Health and Welfare, Narita Hospital, Narita 286-8520, Japan.

Shuntaro Yoshida, Department of Gastroenterology, Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, Tokyo 157-0066, Japan.

Tomonori Aoki, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan.

Fumiko Nagura, Internal Medicine, Chitosefunabashi Ekimae Clinic, Tokyo 157-0054, Japan.

Kosuke Sakitani, Department of Gastroenterology, Toyoshima Endoscopy Clinic, Tokyo 157-0066, Japan; Department of Gastroenterology, Sakiatani Endoscopy Clinic, Narashino 275-0026, Japan.

Yosuke Tsuji, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan.

Hayato Nakagawa, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan.

Hidekazu Suzuki, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tokai University School of Medicine, Isehara 259-1193, Japan.

Kazuhiko Koike, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan.

Data sharing statement

Not available.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nardone G, Rocco A, Malfertheiner P. Review article: helicobacter pylori and molecular events in precancerous gastric lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:261–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe M, Kato J, Inoue I, Yoshimura N, Yoshida T, Mukoubayashi C, Deguchi H, Enomoto S, Ueda K, Maekita T, Iguchi M, Tamai H, Utsunomiya H, Yamamichi N, Fujishiro M, Iwane M, Tekeshita T, Mohara O, Ushijima T, Ichinose M. Development of gastric cancer in nonatrophic stomach with highly active inflammation identified by serum levels of pepsinogen and Helicobacter pylori antibody together with endoscopic rugal hyperplastic gastritis. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2632–2642. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Study Group of Millennium Genome Project for Cancer. Sakamoto H, Yoshimura K, Saeki N, Katai H, Shimoda T, Matsuno Y, Saito D, Sugimura H, Tanioka F, Kato S, Matsukura N, Matsuda N, Nakamura T, Hyodo I, Nishina T, Yasui W, Hirose H, Hayashi M, Toshiro E, Ohnami S, Sekine A, Sato Y, Totsuka H, Ando M, Takemura R, Takahashi Y, Ohdaira M, Aoki K, Honmyo I, Chiku S, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Yanagihara K, Yoon KA, Kook MC, Lee YS, Park SR, Kim CG, Choi IJ, Yoshida T, Nakamura Y, Hirohashi S. Genetic variation in PSCA is associated with susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:730–740. doi: 10.1038/ng.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma J, Shen H, Kapesa L, Zeng S. Lauren classification and individualized chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2959–2964. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SK, Kim HJ, Park JL, Heo H, Kim SY, Lee SI, Song KS, Kim WH, Kim YS. Identification of a molecular signature of prognostic subtypes in diffuse-type gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10120-019-01029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura R, Omori T, Mayanagi S, Irino T, Wada N, Kawakubo H, Kameyama K, Kitagawa Y. Risk of lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated-type mucosal gastric carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:32. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou Y, Wu L, Yang Y, Shen X, Zhu C. Risk factors of tumor invasion and node metastasis in early gastric cancer with undifferentiated component: a multicenter retrospective study on biopsy specimens and clinical data. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:360. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawicz-Pruszyński K, Mielko J, Pudło K, Lisiecki R, Skoczylas T, Murawa D, Polkowski WP. Yield of staging laparoscopy in gastric cancer is influenced by Laurén histologic subtype. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:1148–1153. doi: 10.1002/jso.25711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong D, Tang L, Li ZY, Fang MJ, Gao JB, Shan XH, Ying XJ, Sun YS, Fu J, Wang XX, Li LM, Li ZH, Zhang DF, Zhang Y, Li ZM, Shan F, Bu ZD, Tian J, Ji JF. Development and validation of an individualized nomogram to identify occult peritoneal metastasis in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:431–438. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shim CN, Lee SK. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer: do we have enough data to support this? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3938–3949. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdelfatah MM, Barakat M, Lee H, Kim JJ, Uedo N, Grimm I, Othman MO. The incidence of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer according to the expanded criteria in comparison with the absolute criteria of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlth F, Bollschweiler E, Drebber U, Hoelscher AH, Moenig S. Pathohistological classification systems in gastric cancer: diagnostic relevance and prognostic value. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5679–5684. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiménez Fonseca P, Carmona-Bayonas A, Hernández R, Custodio A, Cano JM, Lacalle A, Echavarria I, Macias I, Mangas M, Visa L, Buxo E, Álvarez Manceñido F, Viudez A, Pericay C, Azkarate A, Ramchandani A, López C, Martinez de Castro E, Fernández Montes A, Longo F, Sánchez Bayona R, Limón ML, Diaz-Serrano A, Martin Carnicero A, Arias D, Cerdà P, Rivera F, Vieitez JM, Sánchez Cánovas M, Garrido M, Gallego J. Lauren subtypes of advanced gastric cancer influence survival and response to chemotherapy: real-world data from the AGAMENON National Cancer Registry. Br J Cancer. 2017;117:775–782. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrelli F, Berenato R, Turati L, Mennitto A, Steccanella F, Caporale M, Dallera P, de Braud F, Pezzica E, Di Bartolomeo M, Sgroi G, Mazzaferro V, Pietrantonio F, Barni S. Prognostic value of diffuse vs intestinal histotype in patients with gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:148–163. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura S, Terao S, Adachi K, Kato T, Ida K, Watanabe H, Shimbo T Research Group for Establishment of Endoscopic Diagnosis of Chronic Gastritis. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastric mucosal activity and inflammation. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:136–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimentel-Nunes P, Libânio D, Marcos-Pinto R, Areia M, Leja M, Esposito G, Garrido M, Kikuste I, Megraud F, Matysiak-Budnik T, Annibale B, Dumonceau JM, Barros R, Fléjou JF, Carneiro F, van Hooft JE, Kuipers EJ, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:365–388. doi: 10.1055/a-0859-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Yoshida S, Sakaguchi Y, Nakai Y, Watanabe H, Suzuki H, Tanikawa C, Matsuda K, Koike K. Endoscopy-based Kyoto classification score of gastritis related to pathological topography of neutrophil activity. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5146–5155. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i34.5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimoto M, Ban H, Ichikawa H, Sahara S, Otsuka T, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Furuta T, Andoh A. Efficacy of the Kyoto Classification of Gastritis in Identifying Patients at High Risk for Gastric Cancer. Intern Med. 2017;56:579–586. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, Hayakawa Y, Yamada A, Koike K. Association between gastric cancer and the Kyoto classification of gastritis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1581–1586. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishizawa T, Toyoshima O, Kondo R, Sekiba K, Tsuji Y, Ebinuma H, Suzuki H, Tanikawa C, Matsuda K, Koike K. The simplified Kyoto classification score is consistent with the ABC method of classification as a grading system for endoscopic gastritis. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2021;68:101–104. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.20-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Sakitani K, Yamakawa T, Takahashi Y, Yamamichi N, Hata K, Seto Y, Koike K, Watanabe H, Suzuki H. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody titer and its association with gastric nodularity, atrophy, and age: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4061–4068. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshii S, Mabe K, Watano K, Ohno M, Matsumoto M, Ono S, Kudo T, Nojima M, Kato M, Sakamoto N. Validity of endoscopic features for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection status based on the Kyoto classification of gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2020;32:74–83. doi: 10.1111/den.13486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;3:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaneko S, Yoshimura T. Time trend analysis of gastric cancer incidence in Japan by histological types, 1975-1989. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:400–405. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung SJ, Park MJ, Kang SJ, Kang HY, Chung GE, Kim SG, Jung HC. Effect of annual endoscopic screening on clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment modality of gastric cancer in a high-incidence region of Korea. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2376–2384. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishibayashi H, Kanayama S, Kiyohara T, Yamamoto K, Miyazaki Y, Yasunaga Y, Shinomura Y, Takeshita T, Takeuchi T, Morimoto K, Matsuzawa Y. Helicobacter pylori-induced enlarged-fold gastritis is associated with increased mutagenicity of gastric juice, increased oxidative DNA damage, and an increased risk of gastric carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1384–1391. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jónasson L, Hallgrímsson J, Olafsdóttir G. Gastric carcinoma: correlation of diagnosis based on biopsies and resection specimens with reference to the Laurén classification. APMIS. 1994;102:711–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1994.tb05224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansson LE, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Can endoscopic biopsy specimens be used for reliable Laurén classification of gastric cancer? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:711–715. doi: 10.3109/00365529609009155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Kim JH, Rhee K, Huh CW, Lee YC, Yoon SO, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI. Undifferentiated early gastric cancer diagnosed as differentiated histology based on forceps biopsy. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waldum HL, Fossmark R. Types of Gastric Carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19124109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung DH, Park YM, Kim JH, Lee YC, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI, Kim JW, Choi SH, Hyung WJ, Noh SH. Clinical implication of endoscopic gross appearance in early gastric cancer: revisited. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3690–3695. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanesaka T, Nagahama T, Uedo N, Doyama H, Ueo T, Uchita K, Yoshida N, Takeda Y, Imamura K, Wada K, Ishikawa H, Yao K. Clinical predictors of histologic type of gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1014–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yao K, Oishi T, Matsui T, Yao T, Iwashita A. Novel magnified endoscopic findings of microvascular architecture in intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Yao K, Ishida T, Togo K, Yanai Y, Fukuda M, Motomura M, Narita R, Murakami K. Histologic differentiation and mucin phenotype in white opaque substance-positive gastric neoplasias. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E597–E604. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanesaka T, Sekikawa A, Tsumura T, Maruo T, Osaki Y, Wakasa T, Shintaku M, Yao K. Absent microsurface pattern is characteristic of early gastric cancer of undifferentiated type: magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 80: 1194-1198. :e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamada T, Tanaka A, Yamanaka Y, Manabe N, Kusunoki H, Miyamoto M, Tanaka S, Hata J, Chayama K, Haruma K. Nodular gastritis with helicobacter pylori infection is strongly associated with diffuse-type gastric cancer in young patients. Dig Endosc. 2007;19:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ford AC, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2020;69:2113–2121. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Kusumoto C, Imada T, Hamada F, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Mitsuhashi T, Okada H. Risk of gastric cancer in the second decade of follow-up after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:281–288. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01639-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not available.