Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine experiences and attitudes toward care offered by chiropractors and prescription drug therapy offered by medical physicians for patients who have back pain.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey measured patients with back pain (n = 150) seeking care within an academic primary care setting. A survey assessed patient experiences, beliefs, and attitudes regarding chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy. Two samples of patients in the New Hampshire region included 75 patients treated by a doctor of chiropractic (DC) and 75 treated by a medical primary care physician (PCP). The 30-item survey was sent to existing and new patients between February 2019 and January 2020. Between-group comparisons were examined to test rates of reporting and to determine the mean difference in the total number of office visits between the 2 samples.

Results

Patients treated by both DCs and PCPs reported high overall satisfaction with chiropractic care received for low back pain with no significant differences between groups. The majority in both groups reported that seeing a DC for back pain made sense to them (95% of patients treated by a DC and 75% of patients treated by a PCP) whereas the minority reported that taking prescription drugs for back pain made sense (25% of patients treated by a DC and 41% of patients treated by a PCP). There was no statistical difference between groups when patients were asked if seeing a chiropractor changed their beliefs or behaviors about taking pain medication. Significant differences were found between groups for agreement that chiropractic care would be a suitable treatment for back pain (79% of patients treated by a DC and 45% of patients treated by a PCP). There were 7% of patients treated by PCP and 23% of the patients treated by DC who agreed that a DC would be the first health care provider they would like to see for their general health needs.

Conclusions

In this sample of patients, patient satisfaction regarding chiropractic care received for back pain was high. There were differences between patient groups about preferences for treatment for back pain. Our results indicate that patients reported that seeing a DC for back pain did not change their beliefs or behaviors regarding prescription drug therapy provided by their medical PCP.

Key Indexing Terms: Chiropractic; Patient Satisfaction; Prescription Drug; Medication Therapy Management; Back Pain; Physicians, Primary Care

Introduction

Spine pain, which includes back and neck pain, impose high costs, disability, and decreased quality of life on patients, and back and neck pain are 2 of the most common reasons for individuals to seek chiropractic care.1 Back pain–related care is the largest contributing factor to increased outpatient health care expenditures.2 Moreover, the medical management of back pain can be hazardous, as evidenced by the crisis of opioid prescribing–back pain is the most common condition for which opioids are prescribed.3 Evidence-based clinical guidelines now recommend nonpharmacological therapies such as spinal manipulation, rather than opioid analgesics, as the first-line approach to care of back pain.4 Spinal manipulation has been found to be a cost-effective addition to usual medical care and was associated with increased levels of quality-adjusted life-years in patients with back pain compared to usual medical care alone.5 Chiropractors frequently treat back pain with spinal manipulation, and prior research has demonstrated a cost advantage to seeing a chiropractor first. Paid costs associated with an episode of care for low back pain initiated with a doctor of chiropractic (DC) clinician were shown to be nearly 40% less compared to paid costs initiated by a medical doctor.6

The National Health Interview Study reported that the prevalence of chiropractic care use among US adults was relatively stable, with estimates ranging between 7.5% and 8.6%.7,8 Owing to the increasing importance of patient satisfaction within the health care system, numerous studies have examined patient satisfaction with chiropractic care.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 In a national phone survey, attitudes and utilization among chiropractic users and nonusers were assessed and an overall high satisfaction rate with chiropractic care was found.13 However, among patients receiving health care in an academic primary care setting, little is known about their experiences and beliefs regarding chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy. Thus, an examination of patient experiences, attitudes, and beliefs regarding the treatment of back pain is timely and warranted. A recent national survey study surveyed over 5,000 respondents with the aim of examining patient experiences of chiropractic care.9 A total of 13.7% of those surveyed said that they had seen a DC in the last 12 months. The authors reported that 61.4% of respondents believed that chiropractic care was effective at treating neck and back pain and 52.6% thought that DCs were trustworthy. However, according to their study, 24.2% of the respondents said that chiropractic care was dangerous. The authors noted that as respondents’ likelihood to use a DC increased, their perceptions of effectiveness and trustworthiness of chiropractic care also increased, and patient perceptions of danger decreased. Respondents were also more likely to be white, married, female, and employed.9

Another recent study reported on 544 patients’ expectations with various aspects of their chiropractic care using a cross-sectional survey design.10 According to the authors, 92% of patients reported reduced pain and 80% reported increased mobility owing to their chiropractic care. Additionally, 20% of the patients who responded to the survey reported unforeseen or unpleasant reactions, including tiredness or fatigue and extra pain, and some reported concern about pain, tingling, and numbness after a chiropractic visit.10 According to the authors, patients reported a high level of satisfaction with their chiropractic care; however, there were some areas where patients reported that their expectations were not fully met—these included determining the cost of their treatment plan during their first consultation, connecting with a patient's primary care physician, and having a discussion about a referral to another health care provider.10

Although interest in understanding patient expectations and experiences is growing, there are still patient perspectives on chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy that should be investigated. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to assess patient perspectives on prescription drug therapy vs chiropractic care and to examine patients’ overall beliefs and attitudes regarding their chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy for back pain. This study examined experiences, beliefs, and attitudes between 2 samples of patients: (1) those who were seen and treated for their back pain by a DC, and (2) those who were seen and treated for their back pain by a medical primary care physician (PCP) in the same academic primary care facility. Based on previous literature,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 we hypothesized that patients’ views on chiropractic care would predominantly be positive and those who received chiropractic care would be more likely to disagree with prescription drug therapy treatment for back pain. Additionally, we were interested in examining whether being treated by a chiropractor for back pain had an influence on a patient's beliefs and behaviors regarding prescription drug therapy. We expected that patients treated by the DC would be less inclined to use prescription medications for back pain and this would result in a self-reported change in beliefs or behaviors toward prescription drug therapy due to seeing or being treated by a chiropractor. This study differs from previous surveys, because all the respondents were receiving care in the same primary care office at an academic medical center.

Methods

Setting and Survey Development

The clinical site of this research was an outpatient primary care clinic at an academic medical center in the New Hampshire region. Patient services offered by the primary care clinic included those of a DC who provided care to patients with back pain. Chiropractic care focused on primary spine care model protocols to determine the most likely cause of the patient's pain, and then the most appropriate care was implemented (ie, joint-related pain: manipulation, disc-related pain: McKenzie-based therapy, chronic nerve pain: neuromobilization, myofascial pain: various manual therapies). For spinal manipulation, diversified technique was the primary chiropractic technique used. All patients treated by a DC received education on the natural history of back pain, guideline-concordant recommendations on remaining active, and appropriate exercises based on evaluation.

Usual care provided by medical PCPs for patients with acute back pain included recommendations to rest, use some type of topical cream, apply heat or ice packs, and take medications for pain (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen) unless contraindicated, and also include referral to a physical therapist. Patients with persistent pain or those with subacute cases would receive usual care and may be prescribed an oral steroid prescription medication instead of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Physical therapy may have been used for most patients being seen by their medical PCP. Usual care provided by medical PCPs for chronic care included variations in the treatment recommendations noted above and referral to the pain clinic and/or a functional restoration program with some patients receiving a steroid epidural injection. When indicated, non-habituating muscle relaxants and opioids might be considered.

We developed a self-report patient survey to administer to patients seeking treatment for spine-related pain to assess and examine whether the inclusion of a DC within a primary care setting is beneficial as assessed by patient overall satisfaction. Specifically, we developed a patient survey to assess patient experiences and attitudes with their treatment and care for their spine-related pain as well as patient satisfaction and the effectiveness of the treatments from the perspective of the patient. The anonymous survey was approved by the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Southern California University of Health Sciences institutional review boards and administered online through Research Electronic Data Capture, which is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant browser-based software developed by Vanderbilt University.

Before administration of the survey, the survey was reviewed and validated by multiple DCs, a primary care physician, and university students and staff. Feedback from the reviewers was incorporated and the survey was accordingly revised for administration to patients. The survey consisted of 30 questions in total and used multiple response formats including multiple choice, open-ended, and Likert-type scales. The items pertaining to beliefs about treatment come from the Low Back Pain Short Form questionnaire developed by Dima et al.14 In addition to inquiring about chiropractic care for back pain, we included items pertaining to patient perspectives on prescription drug therapy.

Participants

Between February 2019 and January 2020, we administered the survey anonymously to existing and new adult patients seen in an academic primary care setting for a complaint of spinal pain. Patients self-selected their provider type. The survey was administered online via tablets using the university's Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant data collection and management software Research Electronic Data Capture15 (which is a secure research electronic data capture software). Patients were administered the survey at the medical center, typically during a follow-up health care visit appointment. A total of 156 patients were administered the survey, but 150 patients completed the survey of a possible 500 to 600 patients who could have potentially been seen for back pain during February 2019 to January 2020. Since the survey was anonymous, signatures were not required on informed consent documents; however, for patients who volunteered to participate, prior to administering the survey, medical staff verbally reviewed all elements of informed consent and emphasized that participation in this study was voluntary. Patients who agreed to participate were asked to report about their level of agreement (or disagreement) regarding various aspects of their treatment (experiences and attitudes). Participants were instructed to select the most appropriate response based on their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs regarding chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy. A copy of the survey is provided as a supplementary file (see supplementary file available online).

Ethics

This study received expedited review and approval from the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (study 00030288.)

Analysis

Two groups of patients were assembled for comparison: (1) those treated by a DC, and (2) those treated by a medical PCP. We had an initial goal to obtain at least 75 respondents with complete data in each group. Descriptive statistics were used for an overall examination of the respondents’ demographic data. Group differences in rates of agreement were examined using chi-square analyses, and group mean differences in the number of visits to the clinic were examined using t tests. For most items, patients were instructed to provide their level of agreement with the statement where response options ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree. For purposes of analyses, response options strongly agree and agree were combined together and similarly, the response options strongly disagree and disagree were combined together for all subsequent analyses presented. Combining responses helps to limit rare responding and small cell sizes.

We conducted a preliminary analysis on the first 25 respondents of the survey to examine clarity of the items, including rates of responding to each item. Some respondents provided feedback regarding the clarity of the items pertaining to our inquiries about prescription medications (not including over-the-counter medications). Accordingly, we revised those items to clarify that we are inquiring about prescription medications. We included responses from the first 25 respondents in our overall analyses.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 156 respondents were administered the survey and 150 respondents completed the patient survey, with 75 in each sample. The 2 samples were comparable in mean age, distribution of sex, and education, and over 90% of each sample identified as white or Caucasian. However, the 2 samples significantly differed on number of visits to the clinic for low back pain with patients treated by a DC reporting a significantly higher number of visits (t = 5.813; df = 148; P < .001) (Table 1). In personal (prior) experience with seeing a DC, 85% (n = 64) of the patients treated by a DC said that they had seen a DC in the last 6 months compared with only 13.4% of the patients treated by a PCP who reported that they had seen a DC in the last 6 months. Approximately 13% of those who were treated by a medical PCP said that they had seen an external chiropractor within the last 6 months; thus, patients treated by a PCP may have had experiences with a DC in the past, which may have influenced their responding to our survey.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 150)

| Patient Sample | Mean Age (SD), Range in Years | Sex (% Female) |

Race/Ethnicity | Education (% college and above) | Average No. (SD), Range of Visits for LBPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC clinician (n = 75) |

47 (17.6) Range: 17-77 |

69% (n =52) |

93% white (n = 70) |

80% (n = 60) |

4.68* (4.4) 0-25 |

| Primary care physician (n = 75) |

47 (17.3) Range: 18-90 |

64% (n = 48) |

95% white (n = 71) |

76% (n = 57) |

1.43 (2.0) 0-12 |

Question asks, ”In the last 12 months, approximately how many visits have you made to this office for low back pain? (1, 2, 3,…).” Patients who reported 0 may be indicating a first-time visit for low back pain.

Significant difference in average number of visits to the clinic between the 2 groups P < .001.

DC, doctor of chiropractic; PCP, primary care physician; SD, standard deviation.

Patients’ Overall Satisfaction With Care and Prescription Drug Therapy

We examined patients’ level of agreement regarding overall satisfaction with chiropractic care between the 2 patient groups; 90% of the patients treated by a DC agreed that they were satisfied with their care. Seventy-three percent of patients treated by a PCP also agreed that the chiropractic care they received presumably at some point in the past was satisfactory (however, the overall response pattern between the 2 groups was not significant (χ2 = 5.49; P = .06). Patients’ level of agreement regarding their overall satisfaction with conventional medical care also revealed similar response rates of satisfaction (approximately 60% for each group) between the 2 patient groups with no observed difference in the distribution of responses between the 2 patient groups; χ2 = 1.10; P = .58; n = 137. Lastly, we examined respondents’ level of agreement with their overall satisfaction with prescription drug therapy for back pain. Of those who indicated that this question was applicable to them, approximately one-third agreed that they were satisfied with the prescription drug therapy they had received, while another third reported being neutral (undecided). Thus, no significant association between the patients treated by a DC and patients treated by a PCP was observed for this item (χ2 = 1.14; P = .565; n = 58).

Beliefs and Attitudes About Chiropractic Care and Prescription Drug Therapy

Table 2 displays patient beliefs and attitudes regarding chiropractic care and prescription drug therapy between the 2 patient groups (those treated by a DC or PCP). We observed significant associations between the 2 patient samples for their reported levels of agreement/disagreement for several items. Seven percent of the patients treated by a PCP and 23% of the patients treated by a DC agreed that a DC was the first health care provider that they would like to see for their general health needs; this observed difference in the reported levels of agreement/disagreement between the 2 patient samples was significant (χ2 = 7.69; P = .02).

Table 2.

Patient Reported Experiences and Beliefs Regarding Chiropractic Care and Prescription Drug Therapy (N = 150)

| Question | Agree + Strongly Agree, % |

Neutral (undecided), % |

Disagree + Strongly Disagree, % |

Chi-square | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC (%) | PCP (%) | DC (%) | PCP (%) | DC (%) | PCP (%) | |||

| A chiropractor is the first health care provider I want to see about my general health. | 23 | 7 | 24 | 28 | 53 | 65 | 7.69 | .021 |

| A PCP is the first health care provider I want to see about my general health. | 80 | 88 | 13.3 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 2.06 | .328 |

| Seeing a chiropractor as a patient for low back pain changed my beliefs about taking pain medication (n = 87). | 45 | 42 | 34 | 26 | 21 | 32 | 1.38 | .501 |

| Seeing a chiropractor as a patient for low back pain changed my behaviors about taking pain medication (n =83). | 40 | 35.5 | 29 | 29 | 31 | 35.5 | 0.254 | .881 |

| Seeing a chiropractor for back pain makes sense. | 95 | 75 | 5.3 | 24 | 0 | 1.3 | 11.68 | .001 |

| Taking/having prescription drugs for back pain makes a lot of sense. | 25 | 41.3 | 35 | 37.3 | 40 | 21.3 | 7.215 | .027 |

| I think seeing a chiropractor for back pain is useless. | 0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 20 | 97.3 | 79 | 12.43 | <.001 |

| I think taking prescription drugs is pretty useless for people with back pain. | 19 | 8 | 25 | 31 | 56 | 61 | 3.76 | .152 |

| I have concerns about seeing a chiropractor for my back pain. | 2.7 | 24 | 6.7 | 16 | 91 | 60 | 20.36 | P < .001 |

| I have concerns about taking/having prescription drugs for my back pain. | 52 | 40 | 12 | 29 | 36 | 31 | 6.946 | .031 |

| I am confident chiropractic care would be a suitable treatment for my back pain. | 79 | 45 | 20 | 41.3 | 1.3 | 13.3 | 19.65 | P < .001 |

| I am confident prescription drugs would be a suitable treatment for my back pain. | 15 | 19 | 24 | 48 | 61.3 | 33.3 | 12.57 | .002 |

| In general, I have been satisfied with the chiropractic care I have received. | 90.4 | 73.5 | 4.1 | 14.7 | 5.5 | 11.8 | 5.49 | .064 |

| In general, I have been satisfied with the prescription drug therapy I have received for low back pain. (n = 58) | 37.5 | 29.4 | 32.4 | 37.5 | 38.2 | 25 | 1.14 | .565 |

Items regarding beliefs about back pain are modified from Dima et al Treatment Beliefs in LBP questionnaire14; responses for agree and strongly agree were collapsed together owing to smaller sample sizes; likewise responses for disagree and strongly disagree were collapsed together; The neutral response undecided was left as is; P = probability value. Fisher Exact test was conducted to determine the probability for items with cell counts smaller than 5 –in these instances, the exact probability is reported in Table 2.

DC, doctor of chiropractic; PCP, primary care physician.

Additional significant overall associations to note include 25% of the patients treated by a DC agreed that taking prescription drugs for their back pain made sense compared with 41% of patients treated by a PCP (40% of patients treated by a DC disagreed with this statement compared to 21% of patients treated by a PCP). Regarding the statement “I have concerns with taking/having prescription drugs for my back pain,” 52% of patients treated by a DC agreed with this statement compared to 40% of patients treated by a PCP. Twenty-nine percent of patients treated by a PCP reported they were neutral (undecided).

In Table 2, 79% of patients treated by a DC agreed with the statement “I am confident chiropractic care would be a suitable treatment for my back pain” compared to 45% of patients treated by a PCP who also agreed with this statement; however, 41% of patients treated by a PCP reported being neutral (Table 2).

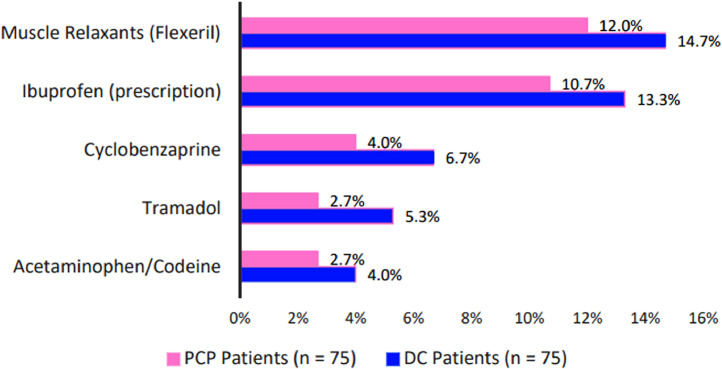

For the question “Have you used prescription medication(s) for low back pain?,” of the patients who said that this question was applicable to them, 50% of the patients treated by a DC reported they had taken prescription medications for low back pain at some point, whereas 55% of patients treated by a PCP said that they had taken prescription medications for their low back pain. The prescription medications that had the highest endorsement rate included prescription ibuprofen and muscle relaxants such as Flexeril (cyclobenzaprine) and Zanaflex (tizanidine) (with approximately 10% to 15% of the patients endorsing these) (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Top 5 patient-endorsed prescription medications used for low back pain. Of the patients who said that they had taken prescription medications at some point for their low back pain, these are the top prescription medications that they reported taking.

Discussion

The present study examined patient perspectives, attitudes, and beliefs on prescription drug therapy and chiropractic care between 2 groups of patients: (1) those who were seen and treated for their back pain by a DC; and (2) those who were seen and treated for their back pain by a PCP. We expected that patients’ views on chiropractic care would predominantly be positive even within a primary care setting and those who received chiropractic care would be more likely to disagree with the effectiveness of prescription drug therapy as a treatment for their back pain.

Overall, the results confirmed our expectations, and patient reports demonstrated high agreement that it made sense to see a DC for back pain. Additionally, there were no significant group differences between the patients treated by a DC and those treated by a PCP regarding their agreement with overall satisfaction with the chiropractic care received for low back pain; both groups reported high overall satisfaction with the chiropractic care. Additionally, similar to the 2015 Weeks et al. study,9 most of the respondents for the present study agreed that chiropractic care was a suitable treatment for back pain, although the response rates for the 2 groups significantly differed. A very small percentage of patients treated by a DC said that they had concerns regarding chiropractic care for their back treatment, which is similar to the notion and findings reported by Weeks et al., suggesting that as patients’ experience with a DC increases their reported rates of concerns decrease.9 Presumably, the respondents in the DC group had more experience with a chiropractor compared to the patients treated by a PCP, thus potentially explaining their respective reported rates of concern.

This survey examined whether being treated by a DC for back pain may have had an influence on a patient's beliefs and behaviors regarding prescription drug therapy (ie, if the patients treated by a DC would report higher rates of agreement). We did not observe significant differences in the reported rates of agreement between the 2 patient samples, thereby suggesting that seeing a DC for back pain does not influence attitudes toward drug therapy. This may have been because the setting of the survey was an academic primary care medical center where patients are prescribed medications for various ailments including pain, which patients may see as necessary or effective depending on the condition being treated. Thus, there may also be an inherent bias in the samples because the survey was conducted within a primary care facility. Additionally, it may be that with a larger sample size we may have observed trends indicating or suggesting a change in beliefs and/or behavior toward prescription drug therapy. Moreover, the patients treated by a DC were administered the survey during a follow-up visit (typically, during a second or third visit); thus they may not have had the chance to develop and solidify any beliefs associated with change in behavior. Moreover, both samples of patients agreed that a PCP was the first health care provider that they want to see for their general health needs.

Current evidence-based guidelines for low back pain include that nonpharmaceutical services, such as chiropractic care, should be considered as first-line therapy before considering drug therapy.4 The patients in this study, who were likely unaware of these guidelines, reported they valued trying chiropractic care but at the same time may have been conditioned to reach for ubiquitous painkillers like ibuprofen. These findings suggest that the medical system could do a better job in (1) medical education about the American College of Physicians guidelines to medical physicians on the application of and including recommendations for nonpharmacological approaches as initial interventions for back pain, (2) development of a workforce able to provide guideline-concordant care, (3) seamless integration of conventional (ie, medical) and complementary (ie, chiropractic) care services, and (4) making such care more easily accessible and affordable.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this research is a putative reduction in selection bias, because both the chiropractic and the medical samples received care in the same academic primary care setting. Thus, not only was the academic primary care setting relatively novel for a study of chiropractic care, but also the propensity for seeking chiropractic care vs medical care was likely equivocal between groups.

However, the results from the present survey study should also be considered with a few limitations in mind. First, the patient survey was administered at only 1 clinical site therefore the findings may not necessarily be applicable to patients in other regions of the United States. The study of 1 site enabled us to examine patient perspectives, attitudes, and beliefs regarding their care within an academic primary care setting (and direct comparisons could be made between the perspectives of patients treated by PCPs and DCs). By collecting data on 150 respondents, we had the statistical power to determine whether group differences between the 2 samples were significant. However, some items where we did not observe significant differences between the groups could have resulted from a smaller valid N (meaning that those items were applicable to a fewer number of patients), which could have affected the ability to detect a difference. Additionally, the patients treated by PCP may have seen an external DC at some point, therefore it is unknown if their responses to items pertaining to experience with chiropractic care may have reflected their prior experience. For example, we would estimate that approximately 25% to 30% of patients with back pain would have seen a DC before seeing a PCP. Similarly, perspectives of patients treated by a DC on seeing a PCP for their general health care needs was also positive. This in turn may have been influenced prior positive experiences with a PCP. Moreover, as typically observed in patient self-reported surveys, it is possible that the current survey results may have been affected by response bias as patients in each group would favorably rate their chosen provider type. Patients typically self-select to their preferred provider type, which may have also affected the survey findings. We also altered the anchors for the survey questions from the original Dima study (changing “neither agree nor disagree” to “undecided”),14 which could have changed how people answered each item. And we did not fully test this survey instrument for validity with patients before using it in this study.

A future direction would be to more clearly distinguish between over-the-counter medications and prescription medications as well as differentiate between patients with acute and chronic back pain with our survey.

Conclusion

The present study of 150 patients with low back pain provides information about patient experiences, beliefs, and attitudes toward chiropractic care provided by DCs and prescription drug therapy provided by medical PCPs for patients with back pain in an academic medical care setting. Overall, our study showed high rates of satisfaction with chiropractic care. Although most patients reported that a DC would not be their choice for the first health care provider they would see for their general health care needs, most patients agreed that it makes sense to see a DC for the treatment of their back pain, which is consistent with current evidence-based back pain treatment guidelines. Most reported preference for a medical PCP for their general health care needs, which supports models that integrate care that is valued for other concerns, such as chiropractic care for back pain, within primary care settings. Patients from both groups agreed that chiropractic care would be a suitable treatment for back pain and most disagreed that prescription drugs would be a suitable treatment for their back pain. Ultimately, our survey results indicate that seeing a DC for back pain did not change patient beliefs or behaviors regarding prescription drug therapy provided by their medical PCP.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2021.02.003.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

Contributorship Information

Concept development (provided idea for the research): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Design (planned the methods to generate the results): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Supervision (provided oversight, responsible for organization and implementation, writing of the manuscript): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Data collection/processing (responsible for experiments, patient management, organization, or reporting data): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G.

Analysis/interpretation (responsible for statistical analysis, evaluation, and presentation of the results): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Literature search (performed the literature search): S.B., J.M.W.

Writing (responsible for writing a substantive part of the manuscript): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Critical review (revised manuscript for intellectual content, this does not relate to spelling and grammar checking): S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Other (list other specific novel contributions):Paper Revisions: S.B., J.M.W., J.M.G., L.A.K.

Practical Applications.

-

•

Most patients in this study agreed that it made sense to them to see a DC.

-

•

Most patients reported that they would not choose a chiropractor for their general health care needs.

-

•

The field of medicine should do a better job to discourage the use of prescription medications (opioids) for back and spine pain.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin R. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2008. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children: United States, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK, Lee MJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997-2006. Spine. 2009;34:2077–2084. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1fad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson TJ, Edlund MJ, Steffick DE, Tripathi SP, Sullivan MD. Epidemiology of regular prescribed opioid use: results from a national, population-based survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;7(166):514–530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UK BEAM Trial Team United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation (UK BEAM) randomised trial: effectiveness of physical treatments for back pain in primary care. BMJ. 2004;329(7479):1377. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38282.669225.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liliedahl RL, Finch MD, Axene DV, Goertz CM. Cost of care for common back pain conditions initiated with chiropractic doctor vs. medical doctor/doctor of osteopathy as first physician: experience of one Tennessee-based general health insurer. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(9):640–643. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;(343):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Public perceptions of doctors of chiropractic: results of a national survey and examination of variation according to respondents’ likelihood to use chiropractic, experience with chiropractic, and chiropractic supply in local health care markets. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(8):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacPherson H, Newbronner E, Chamberlain R, Hopton A. Patients’ experiences and expectations of chiropractic care: a national cross-sectional survey. Chiropr Man Therap. 2015;23(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12998-014-0049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gemmell HA, Hayes BM. Patient satisfaction with chiropractic physicians in an independent physicians’ association. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(9):556–559. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.118980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowell RM, Polipnik J. A pilot mixed methods study of patient satisfaction of chiropractic care for back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(8):602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaumer G. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with chiropractic care: survey and review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(6):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dima A, Lewith GT, Little P. Patients’ treatment beliefs in low back pain: development and validation of a questionnaire in primary care. Pain. 2015;156(8):1489–1500. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – ametadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.