Abstract

This database study analyzes the risk of medical malpractice associated with the use of telemedicine for the diagnosis or management of skin cancer.

Telemedicine use has increased substantially in recent years, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 Although patients and dermatologists have become more comfortable with telemedicine and its benefits, concerns remain regarding suboptimal diagnosis and management, image quality, internet access, patient triage, uncoordinated care by direct-to-consumer companies, and insurance coverage.3 In dermatology, issues related to the diagnosis and management of skin cancer are among the most common malpractice claims and account for the largest sums awarded.4 Although research suggests that telemedicine has a low risk for malpractice,1 to our knowledge, the malpractice risk associated with the use of telemedicine for the of management skin cancer has not been studied. This study sought to assess all publicly reported cases of malpractice associated with the telemedicine management of skin cancer.

Methods

This database study used only publicly available data and did not involve human participants. It was therefore exempt from review by the institutional review boards at Yale University and Massachusetts General Hospital and the requirements for patient informed consent.

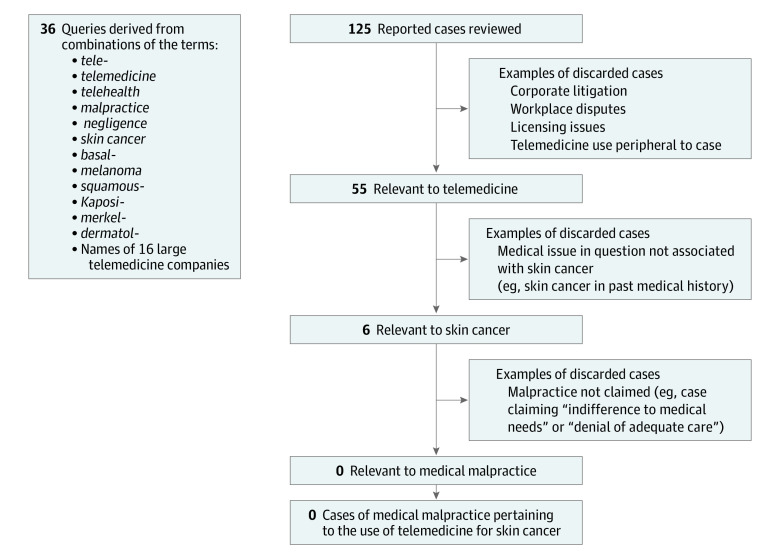

Using previously described methodologies,1,5 we performed a search of the LexisNexis legal case database between January 15 and February 15, 2021, for all publicly reported cases from federal and state courts. A reported case includes any judicial action of a court, including judgments, rulings, opinions, dismissals, or other official actions. We searched for cases dated from January 1, 1950, to January 1, 2021, using 36 queries derived from relevant terms, including telemedicine, malpractice, and skin cancer (Figure).

Figure. Search Methodology and Inclusion Criteria.

One of us (A.L.F.) reviewed the reported cases for their relevance to telemedicine. Cases were excluded if they did not involve medical practice allegations or if the medical issues did not pertain to the diagnosis or management of skin cancer. Cases were not limited by medical specialty.

Results

The search queries identified 125 reported cases (Figure). No cases with a judgment or final finding of malpractice or medical negligence in conjunction with the use of telemedicine for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer were identified. In 6 identified cases, incarcerated patients filed lawsuits claiming “indifference to medical needs” or “denial of adequate care” associated with the management of skin cancers in which telemedicine was a component of diagnosis or management. These cases did not include claims of medical malpractice.

Discussion

In this study, there were no reported cases with findings of medical malpractice associated with the telemedicine management of skin cancer. Given that approximately 25% of medical malpractice claims are associated with reported court cases, these findings suggest low historical malpractice risk.6

Several factors may account for the findings. Telemedicine may mitigate malpractice risk in ways not yet understood, possibly by enabling expedited management and triage. Physicians may limit telemedicine to rashes rather than lesions of concern, or they may expedite in-person visits for patients with lesions of concern. Patients who use telemedicine may be less likely to bring malpractice claims owing to lowered expectations for outcomes or the possibility to seek traditional care. Plaintiff lawyers may be hesitant to bring malpractice claims because of disclaimers on the limited ability to evaluate lesions via telemedicine, the option to seek traditional care, or because the process, marketing, and case law to litigate telemedicine cases has not yet developed. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, but each possibility is difficult to quantify with precision because, despite the accumulated historical volume of telemedicine consultations, robust national data on teledermatology visits by diagnosis code are lacking.

This database study was limited by the inability to assess non–reported malpractice claims, such as those in process or decided via confidential arbitration or settlement prior to a court decision, as well as potential lag-time bias given that legal claims typically arise years after a medical visit. Further research on malpractice claims from insurers, telemedicine companies, or health systems could provide additional perspective on this topic.

References

- 1.Fogel AL, Kvedar JC. Reported cases of medical malpractice in direct-to-consumer telemedicine. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1309-1310. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):349-358. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogel AL, Teng J, Sarin KY. Direct-to-consumer teledermatology services for pediatric patients: room for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(5):887-888. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornmehl H, Singh S, Adler BL, Wolf AE, Bochner DA, Armstrong AW. Characteristics of medical liability claims against dermatologists from 1991 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(2):160-166. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Souza LS, Jalian HR, Jalian C, et al. Medical professional liability claims for Mohs micrographic surgery from 1989 to 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(5):529-532. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.4495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jena AB, Chandra A, Lakdawalla D, Seabury S. Outcomes of medical malpractice litigation against US physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(11):892-894. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]