This cohort study examines the long-term clinical implications of living in a socioeconomically disadvantaged area and other markers of socioeconomic status among adults who survived their first myocardial infarction.

Key Points

Question

Is neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage associated with higher long-term mortality after a first myocardial infarction at a young age?

Findings

In this cohort study of 2097 patients who experienced their first myocardial infarction at or before 50 years of age, living in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with a statistically significantly higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality over an 11-year follow-up period.

Meaning

Results of this study suggest that, among individuals who experienced their first myocardial infarction at a young age, neighborhood and socioeconomic factors played a role in long-term survival.

Abstract

Importance

Socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with poor health outcomes. However, whether socioeconomic factors are associated with post–myocardial infarction (MI) outcomes in younger patient populations is unknown.

Objective

To evaluate the association of neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage with long-term outcomes among patients who experienced an MI at a young age.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study analyzed patients in the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI Registry (at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts) who experienced an MI at or before 50 years of age between January 1, 2000, and April 30, 2016. Each patient’s home address was mapped to the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) to capture higher rates of socioeconomic disadvantage. The median follow-up duration was 11.3 years. The dates of analysis were May 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020.

Exposures

Patients were assigned an ADI ranking according to their home address and then stratified into 3 groups (least disadvantaged group, middle group, and most disadvantaged group).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The outcomes of interest were all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Cause of death was adjudicated from national registries and electronic medical records. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to evaluate the association of ADI with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Results

The cohort consisted of 2097 patients, of whom 2002 (95.5%) with an ADI ranking were included (median [interquartile range] age, 45 [42-48] years; 1607 male individuals [80.3%]). Patients in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to be Black or Hispanic, have public insurance or no insurance, and have higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes. Among the 1964 patients who survived to hospital discharge, 74 (13.6%) in the most disadvantaged group compared with 88 (12.6%) in the middle group and 41 (5.7%) in the least disadvantaged group died. Even after adjusting for a comprehensive set of clinical covariates, higher neighborhood disadvantage was associated with a 32% higher all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.10-1.60; P = .004) and a 57% higher cardiovascular mortality (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.17-2.10; P = .003).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that, among patients who experienced an MI at or before age 50 years, socioeconomic disadvantage was associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality even after adjusting for clinical comorbidities. These findings suggest that neighborhood and socioeconomic factors have an important role in long-term post-MI survival.

Introduction

Although meaningful improvements in cardiometabolic health on a population level have been made throughout the United States over the past 2 decades,1,2,3 substantial disparities persist.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Socioeconomic factors have been associated with poor health outcomes and decreased lifespan even after adjusting for conventional risk factors.4,5,11,12,13,14,15,16 Working to understand and reduce these stark disparities has been a major focus of governments and national societies, as recently highlighted by the American Heart Association’s 2030 Impact Goals.3,10,12,17,18,19,20

A growing body of evidence suggests that lower socioeconomic status is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes among younger adults.21 Although the association between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease is well established, less is known about the role of neighborhood socioeconomic factors in outcomes after a myocardial infarction (MI), particularly in a young patient population.

Previous studies of the association of neighborhood characteristics with health outcomes have used key data from the American Community Survey.22 From this robust repository, factor-based composite measures have been created that incorporate poverty, employment, housing, and educational data to characterize the overall degree of disadvantage in distinct geographic regions.6,22,23,24,25 These measures were found to be associated with hospital readmissions, the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and cause-specific mortality.4,6,13,26,27,28 Understanding whether neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with worse outcomes after an MI among younger adults could inform targeted interventions and public health efforts to reduce mortality.11,29,30,31,32,33

In this cohort study, we aimed to evaluate the association between neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage and long-term outcomes among patients who experienced an MI at a young age (≤50 years), as part of the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI Registry. We hypothesized that neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage would be an independent risk factor in long-term mortality among this patient population.

Methods

The design of the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI Registry has been previously described.34 Briefly, it was a retrospective cohort study from 2 large academic medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts (Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital), that included all consecutive patients who experienced a first MI at or before age 50 years between January 1, 2000, and April 30, 2016. The dates of analysis were May 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. All medical records underwent adjudication by a team of study physicians who used the third universal definition of MI.35 The present analysis included only those patients whose MI was adjudicated to be caused by atherothrombotic coronary artery disease (type 1 MI) and excluded individuals with known coronary artery disease (defined as a previous MI or coronary revascularization). In addition, patients who died during their index hospitalization were excluded from this analysis. Study approval for the YOUNG-MI Registry was granted by the institutional review board at Mass General Brigham, and informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

Risk Factors and Baseline Covariates

For each patient, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors was ascertained through a detailed review of medical records that corresponded to the period up to and including the index admission. Risk factor definitions are provided in eAppendix 1 in the Supplement.

Medical insurance data were obtained from the hospital encounter for MI. Patients were categorized as having commercial, Medicare, Medicaid, no insurance, or unclassified insurance type. If insurance information was not available or missing from the encounter for MI, it was obtained from an alternate encounter within 60 days before or 60 days after the MI. We classified patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid as having Medicaid.

Data on self-reported race/ethnicity for each study member was obtained from the Mass General Brigham medical record.

Home Addresses and Area Deprivation Index

Each patient’s home address was ascertained during the study query period (August 1, 2016, to November 30, 2019) from the electronic data repository at Mass General Brigham, geocoded using the Google Geocoding Application Programming Interface, and mapped to its corresponding census block group. The census block group is a geographically compact region that approximates a typical neighborhood and contains approximately 600 to 3000 people. Patients with an address that could not be accurately geocoded (eg, PO Box addresses) or that was international were excluded. Of the 2097 patients in the cohort, 2002 (95.5%) had a geocodable address (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement has further details).

Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage was measured using the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a standardized score based on census variables. Developed initially in 2003 by Singh23 and updated by Kind et al6 in 2014, the ADI combines 17 measures of employment, income, housing, and education from the American Community Survey.13,14,23,26,27,28 The ADI is freely available and is computed for each census block group in the United States.36 The ADI rankings indexed to the characteristics of each state, ranked from 1 to 10 by groupings of neighborhood deprivation, were linked to each patient according to their home address. A census block group in ADI rank 1 represents the lowest level of socioeconomic disadvantage, whereas a census block group in ADI rank 10 indicates the highest level of socioeconomic disadvantage. Components of the ADI are presented in eAppendix 3 in the Supplement.

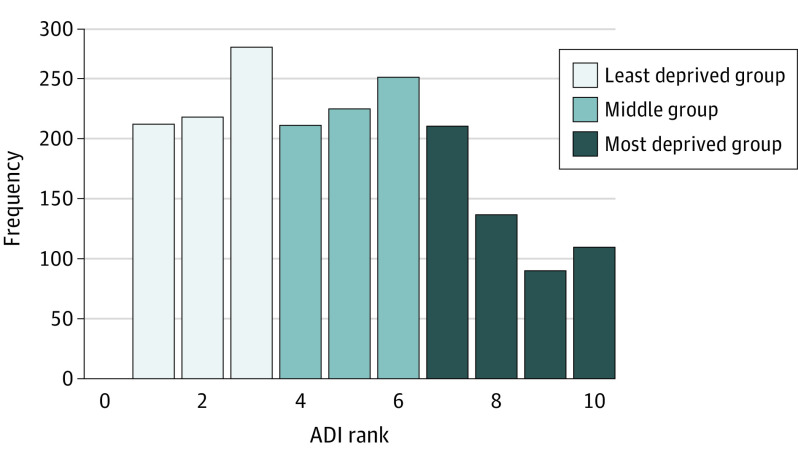

Patients were disproportionately clustered in the more advantaged (lower ADI) state-defined ranks (Figure 1). For simplicity and clarity of presentation, we used the ADI rankings to divide the patients in this study into 3 similarly sized groups: ADI ranks 1 through 3 were categorized into the least disadvantaged group (n = 729), ranks 4 through 6 were categorized into the middle group (n = 709), and ranks 7 through 10 were categorized into the most disadvantaged group (n = 564).

Figure 1. Distribution of the Cohort’s Neighborhood Deprivation by Rank of Area Deprivation Index (ADI).

ADI ranks 1 to 3 were grouped into the least disadvantaged group, 4 to 6 into the middle group, and 7 to 10 into the most disadvantaged group.

Outcomes of Interest

The outcomes of this analysis were all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Determination of vital status is detailed in eAppendix 4 in the Supplement. Cause of death was categorized as cardiovascular, noncardiovascular, or undetermined. The definition of cardiovascular death was adapted from the 2014 American College of Cardiology definitions for cardiovascular end point events.37 Cause of death was assessed while blind to patient demographics or home address.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed with Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC). Categorical variables are reported as frequencies and proportions and were compared using χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. Continuous variables are reported as means or medians and were compared using 2-tailed t tests or Mann-Whitney tests, as appropriate. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by analyzing the Schoenfeld residuals. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to assess the association of neighborhood deprivation as measured by ADI state-indexed rank and to obtain corresponding hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Patients were censored on the date that their source of vital statistics was queried. In the analyses of cardiovascular mortality, individuals who died from noncardiovascular or undetermined causes were conservatively labeled as not experiencing cardiovascular mortality and were censored at their respective dates of death.

Multivariable models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, sex, race, medical insurance, risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia status; tobacco smoking; and marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol use), creatinine level, cardiac catheterization, statin at discharge, and aspirin at discharge. In cases of missing data on baseline covariates, such individuals were omitted from all relevant multivariable analyses.

Medical insurance status was incorporated into the multivariable analyses in 3 distinct ways to explore how insurance may mediate the association of ADI with mortality. The first way, insurance specification 1, was used in the main analysis and incorporated the raw categories of insurance (commercial, public [Medicare and/or Medicaid], and no insurance). The second way, insurance specification 2, grouped insurance categories ([1] commercial and Medicare, and [2] Medicaid and no insurance) to create a marker of personal socioeconomic status. The third way, insurance specification 3, created a binary variable, grouping all insurance types together vs no insurance.

Results

The cohort consisted of 2097 patients, of whom 2002 (95.5%) had a geocodable address with an associated ADI ranking. Among the 2002 patients (median [interquartile range (IQR)] age, 45 [42-48] years; 1607 were male [80.3%] and 395 were female [19.7%]), 729 (36.4%) were in the least disadvantaged group, 709 (35.4%) were in the middle group, and 564 (28.2%) were in the most disadvantaged group (Figure 1).

Across the groupings of ADI ranking, those in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to be Black or Hispanic individuals, to have a higher proportion of public insurance or no insurance, and to have higher rates of traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes (Table 1). A higher proportion of female patients were living in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods compared with other areas (Table 1). In addition, individuals in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods were more likely to smoke tobacco products and use illicit drugs. Finally, individuals in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods were less likely to receive cardiac catheterization and subsequent revascularization during their hospitalization. Other baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The temporal patterns of MI over the study period are shown in eAppendix 9 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics Stratified by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value difference | P value for trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least disadvantaged group (n = 729) | Middle group (n = 709) | Most disadvantaged group (n = 564) | |||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age at the time of MI, median (IQR), y | 45.0 (42.0-48.0) | 45.0 (41.0-48.0) | 45.0 (41.0-48.0) | .18 | .11 |

| Male sex | 621 (85.2) | 554 (78.1) | 432 (76.6) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 108 (14.8) | 155 (21.9) | 132 (23.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 598 (82.0) | 521 (73.5) | 355 (62.9) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Black | 16 (2.19) | 52 (7.33) | 73 (12.94) | ||

| Hispanic | 16 (2.19 | 50 (7.05) | 74 (13.12) | ||

| Other or unknown | 99 (13.58) | 86 (12.13) | 62 (10.99) | ||

| Insurance category | |||||

| Commercial | 571 (78.3) | 472 (66.6) | 296 (52.5) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Public (Medicare or Medicaid) | 72 (9.9) | 131 (18.5) | 144 (25.5) | ||

| None | 32 (4.4) | 57 (8.0) | 73 (13.0) | ||

| Unclassified | 8 (1.1) | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.9) | ||

| Missing insurance data | 46 (6.3) | 43 (6.1) | 46 (8.2) | .28 | .22 |

| History of premature CAD in a first-degree relative | 170 (23.3) | 176 (24.8) | 147 (26.1) | .52 | .25 |

| Index LVEF, mean (SD)a | 54.9 (11.5) | 53.0 (11.7) | 52.8 (11.6) | .003 | .001 |

| ST-elevation MI | 375 (51.4) | 370 (52.2) | 319 (56.6) | .15 | .08 |

| Depression | 74 (10.2) | 87 (12.3) | 91 (16.1) | .005 | .001 |

| Anxiety | 98 (13.4) | 83 (11.7) | 82 (14.5) | .32 | .64 |

| Psychotic disorder | 14 (1.9) | 22 (3.1) | 24 (4.3) | .05 | .01 |

| Length of index hospital stay, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | >.99 | .92 |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension status | 327 (44.9) | 326 (46.0) | 285 (50.5) | .11 | .048 |

| Hyperlipidemia status | 669 (91.8) | 646 (91.1) | 510 (90.4) | .70 | .40 |

| Diabetes status | 108 (14.8) | 155 (21.9) | 132 (23.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Tobacco smoking | 283 (39.4) | 397 (56.7) | 367 (65.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Illicit substance use | 61 (8.4) | 74 (10.4) | 88 (15.6) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Cocaine use | 20 (2.8) | 36 (5.1) | 39 (7.0) | .002 | <.001 |

| Marijuana use | 43 (6.0) | 52 (7.4) | 60 (10.8) | .005 | .002 |

| Alcohol use | 70 (9.7) | 74 (10.5) | 108 (19.5) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Obesity | |||||

| BMI stage 1: ≥30 | 280 (39.7) | 260 (37.5) | 213 (39.4) | .66 | .88 |

| BMI stage 2: ≥35 | 90 (12.7) | 92 (13.3) | 71 (13.1) | .96 | .82 |

| BMI stage 3: ≥40 | 29 (4.1) | 42 (6.1) | 30 (5.6) | .24 | .22 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8 (1.1) | 14 (2.0) | 16 (2.9) | .07 | .02 |

| ASCVD score, median (IQR) | 4.2 (2.3-7.4) | 5.2 (3.2-8.9) | 5.9 (3.7-9.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) | |||||

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 203.1 (289.3) | 202.7 (229.0) | 194.5 (159.0) | .80 | .53 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 193.9 (66.7) | 192.2 (50.3) | 190.8 (49.3) | .64 | .73 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 37.7 (10.5) | 36.4 (10.5) | 36.4 (9.5) | .03 | .04 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 119.4 (54.8) | 119.4 (41.0) | 118.5 (42.3) | .94 | .96 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 88.0 (18.2) | 87.5 (19.3) | 84.5 (22.7) | .005 | .08 |

| Creatinine level, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.5) | <.001 | .73 |

| Patient management | |||||

| Cardiac catheterization | 699 (95.9) | 669 (94.4) | 519 (92.0) | .01 | .003 |

| Coronary revascularization | 637 (87.4) | 613 (86.5) | 455 (80.7) | .002 | .001 |

| Medical therapy at dischargeb | |||||

| Statin | 653 (90.6) | 624 (89.5) | 474 (86.8) | .10 | .04 |

| Aspirin | 691 (95.8) | 663 (95.1) | 505 (92.5) | .03 | .01 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 596 (82.7) | 567 (81.3) | 445 (81.5) | .79 | .57 |

| β-Blocker | 657 (91.1) | 642 (92.1) | 495 (90.7) | .64 | .83 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 435 (60.3) | 419 (60.1) | 355 (65.0) | .15 | .11 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CAD, coronary artery disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction.

SI conversion factors: To convert triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113; HDL, LDL, and total cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; creatinine level to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

For index LVEF, 350 of 2002 patients (17.5%) did not have an available ejection fraction. Such missing observations were distributed as 125 patients (17.1%) in the most deprived group, 123 patients (17.3%) in the middle group, 102 patients (18.1%) in the least deprived group (P = .90). All of the other baseline characteristics had complete or nearly complete data.

For the 1964 patients who survived to hospital discharge.

Outcomes Stratified by Area Deprivation Index

All-Cause Mortality

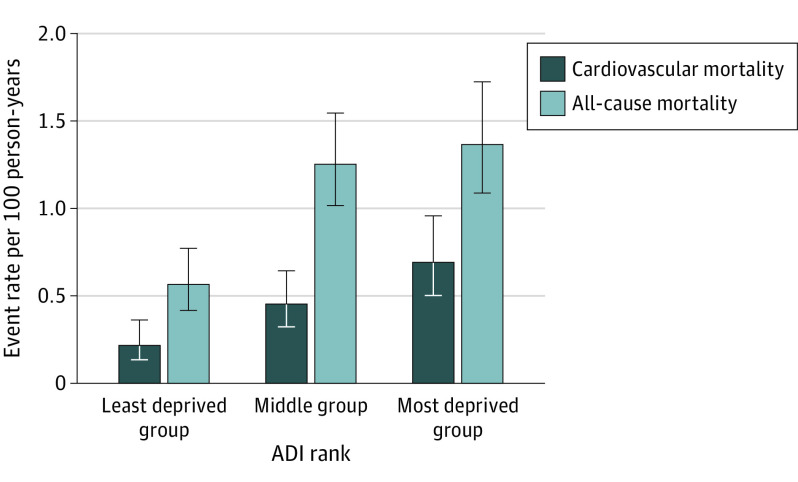

Over a median (IQR) follow-up duration of 11.3 (7.3-14.2) years, 241 of 2002 patients (12.0%) died. Among the 1964 patients who survived to hospital discharge, 74 (13.6%) in the most disadvantaged group compared with 88 (12.6%) in the middle group and 41 (5.7%) in the least disadvantaged group died over the follow-up period (P for trend < .001) (Table 2). In-hospital deaths stratified by grouping of neighborhood disadvantage are shown in eAppendix 10 in the Supplement. Figure 2 shows the corresponding annual all-cause mortality rate for each group.

Table 2. Postdischarge Deaths Stratified by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage.

| Mortality | No. (%) | P value difference | P value for trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least disadvantaged group (n = 721) | Middle group (n = 697) | Most disadvantaged group (n = 546) | |||

| All causes | 41 (5.7) | 88 (12.6) | 74 (13.6) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 16 (2.2) | 32 (4.6) | 37 (6.8) | <.001 | <.001 |

Figure 2. All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Rates per 100 Person-Years by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage After Myocardial Infarction .

The all-cause mortality rate was 1.37 deaths per 100 person-years in the most disadvantaged group, 1.26 deaths per 100 person-years in the middle group, and 0.57 deaths per 100 person-years in the least disadvantaged group. The cardiovascular mortality rate was 0.70 deaths per 100 person-years in the most disadvantaged group, 0.46 deaths per 100 person-years in the middle group, and 0.22 deaths per 100 person-years in the least disadvantaged group. ADI indicates area deprivation index.

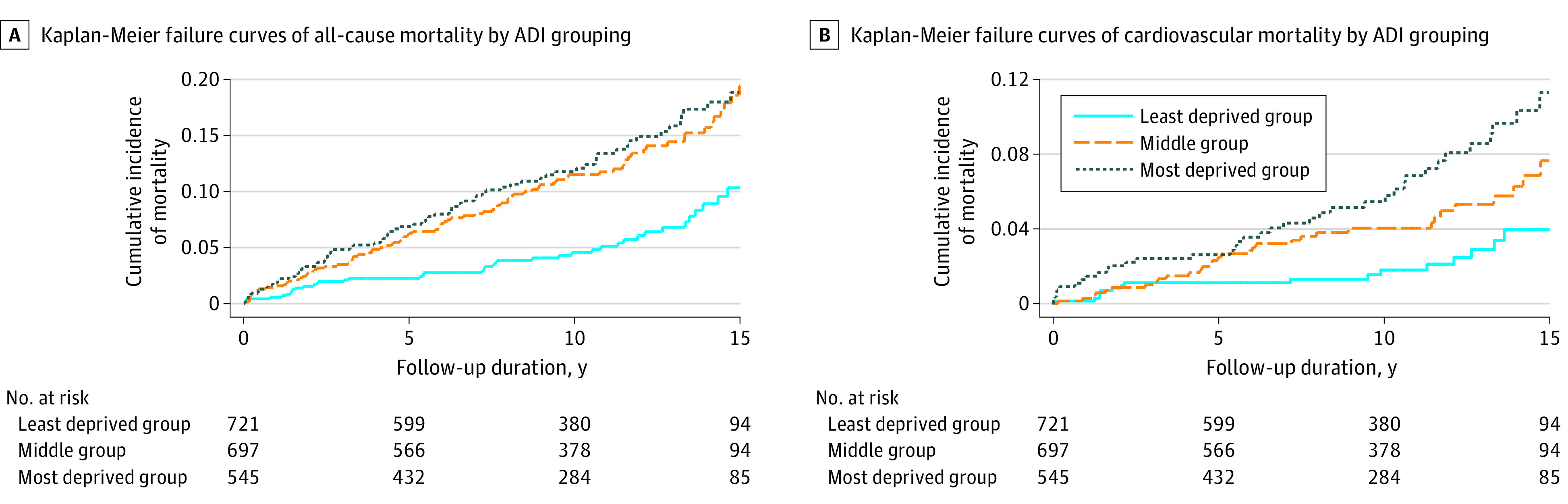

Each single ADI rank increase in neighborhood disadvantage was associated with an unadjusted HR of 1.13 (95% CI, 1.07-1.19; P < .001) for all-cause mortality. After adjusting for available covariates, we found a statistically significant association of rank of neighborhood disadvantage with all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15; P = .006). These findings remained significant when evaluating groups with higher neighborhood disadvantage, as is shown in Figure 3A, with an unadjusted HR of 1.49 (95% CI, 1.25-1.77; P < .001) and an adjusted HR of 1.32 (95% CI, 1.10-1.60; P = .004) for all-cause mortality.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Failure Curves of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Rates by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage After Myocardial Infarction .

Multivariable models were adjusted for the following covariates: age, sex, race, medical insurance, creatinine level, risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia status; tobacco smoking; and marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol use), cardiac catheterization, statin at discharge, and aspirin at discharge. ADI indicates area deprivation index.

CV Mortality

Over the same follow-up period, 115 of the 241 deaths (47.7%) were adjudicated to be cardiovascular in nature. Among the 1964 patients who survived to hospital discharge, 37 (6.8%) individuals in the most disadvantaged group compared with 32 (4.6%) in the middle group and 16 (2.2%) in the least disadvantaged group died of cardiovascular causes (P for trend < .001) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows the corresponding annual cardiovascular mortality rate for each group.

Each single ADI rank increase in neighborhood disadvantage was associated with an unadjusted HR of 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26; P < .001) for cardiovascular mortality. After adjusting for available covariates, we found a statistically significant association of rank of neighborhood disadvantage with cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.23; P = .007). These findings remained significant when evaluating groups with higher neighborhood disadvantage, as is shown in Figure 3B, with an unadjusted HR of 1.72 (95% CI, 1.31-2.27; P < .001) and an adjusted HR of 1.57 (95% CI, 1.17-2.10; P = .003) for cardiovascular mortality. Additional sensitivity analyses with alternate multivariable model inputs are provided in eAppendix 8 in the Supplement.

Association of Insurance Classification With Observed Outcome

We incorporated medical insurance status into the multivariable models in 3 ways as described in the Methods section. The goal was to isolate whether insurance status, either as the category of insurance or by using insurance type and/or status as a marker for individual socioeconomic status, mediates the role of neighborhood disadvantage on long-term mortality. Regardless of how insurance status was incorporated, the multivariable-adjusted results remained statistically significant, with minimal change in effect size (eAppendix 5 in the Supplement).

Sensitivity Analyses

Two separate sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the findings. The first sensitivity analysis related to the medical insurance classification for patients with missing or unclassified insurance data (n = 154 patients [7.7% of the cohort]). Regardless of whether the missing or unclassified insurance data were categorized as commercial or no insurance, the multivariable-adjusted results remained statistically significant, with minimal change in effect size (eTable 1 and eAppendix 6 in the Supplement).

The second sensitivity analysis related to Massachusetts residents vs non-Massachusetts residents. When we limited the analysis to Massachusetts residents (n = 1880 [94.0% of the cohort]), the multivariable-adjusted results remained statistically significant, with minimal change in effect size (eTable 2 and eAppendix 7 in the Supplement).

Discussion

The association between socioeconomic factors and cardiometabolic health has been well documented across a variety of domains.4,8,15 We believe that the findings of this study further demonstrate the role that these factors play in long-term outcomes among a unique cohort of individuals who had an MI at a young age. As illustrated through a robust neighborhood-level deprivation index, individuals who lived in geographic areas with a higher socioeconomic disadvantage experienced higher rates of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality over an approximately 11-year follow-up period. These findings were significant and clinically meaningful even after controlling for an extensive set of clinical and demographic variables.

As a particularly vulnerable group, given the major cardiovascular event they experienced at an early age, the study findings demonstrate the independent association of neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors with mortality. Specifically, we found an 8% (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02-1.15) increase in all-cause mortality and a 13% (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.23) increase in cardiovascular mortality for each single rank increase in socioeconomic disadvantage over a median follow-up duration of 11.3 years. Taken into clinical context, individuals who lived in areas with the highest level of socioeconomic disadvantage had an approximately 80% higher risk for all-cause mortality and an approximately 130% higher risk for cardiovascular mortality compared with those who lived in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods.

We incorporated medical insurance status into the multivariable models in 3 distinct ways, accounting for both the type of insurance and insurance categories as personal markers of poverty. Regardless of how insurance was controlled for in the analyses, the results remained significant, with a negligible change to the effect size. This finding suggests that the presence and type of insurance alone do not mediate the impact of neighborhood-level disadvantage and that neighborhood-level disadvantage is associated with long-term mortality risk beyond personal markers of poverty (eg, Medicaid enrollment or no insurance).

Instead of relying on socioeconomic measures gathered from large geographic areas, such as zip code–level or county-level data, we used census block groups, geographically compact regions comprising between 600 and 3000 people. By linking each patient address with a corresponding census block group, we were able to accurately connect individuals to their local neighborhood, a method that better represents a patient’s immediate socioeconomic surroundings.14,27 The ADI has been implemented widely and has demonstrated the association between neighborhood disadvantage and a host of clinical outcomes.6,13,14,23,26,27

Previous public health research has analyzed how varying neighborhood characteristics may mediate the association between socioeconomic disadvantage and health outcomes. Such mediators include pollution and air quality, exposure to chronic stress, availability of healthy food, and limited access to health care services.10,15,38,39,40,41,42 Specific to the YOUNG-MI Registry, those patients who have had an MI are prescribed a host of medications, such as statins and antiplatelet agents, which have been shown to improve outcomes. For individuals with limited economic resources, medication adherence may be especially challenging.29,30,43 Taken together, the multiple factors associated with living in a disadvantaged neighborhood likely combine to independently impact long-term cardiometabolic outcomes. Although many of these mediators may be challenging to modify, health care systems should actively work to identify patients who are living in conditions of socioeconomic deprivation and focus efforts to ensure robust outpatient care after MI and aggressive secondary prevention measures in an effort to reduce these disparities in outcomes.

The women in this cohort were more likely to reside in neighborhoods with greater disadvantage. Although the relatively small proportion of female patients (19.7%) makes it difficult to generalize, this finding parallels previous research that women are often overrepresented among those living in poverty and may be disproportionately affected by low socioeconomic status.16,44,45,46,47

Although the present study was underpowered to assess the differential role of race/ethnicity in the association of neighborhood deprivation with long-term outcomes, previous work has demonstrated the association of racial/ethnic background with health outcomes.8 The sources of these disparities likely include access to care, unconscious bias, and structural racism.18,19,48,49,50,51,52,53 Future investigations in this field may help inform health policy and targeted interventions for addressing the interplay of racial/ethnic background and neighborhood disadvantage.

As health disparities between racial/ethnic and geographic groups continue to widen throughout the United States,9,10 the present study adds to the growing body of literature that demonstrates that socioeconomic factors contribute to health outcomes. Although prevention efforts have traditionally focused on the underlying risk factors and disease of the individual patient, interventions that target communities and sources of socioeconomic stress may lead to improvements in outcomes. We believe this study reinforces the need to better understand the underlying mechanisms that link socioeconomic disadvantage to poor outcomes in cardiovascular disease as well as the need to identify robust and comprehensive strategies to reduce this excess risk.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has multiple strengths. Among these strengths were the detailed adjudication of patient-level data, the linkage of patients to neighborhoods at a highly granular level, and the long-term follow-up of patients in the YOUNG-MI Registry. We believe that the use of the ADI as a comprehensive measure of social risk places this study within the growing body of literature linking indices of neighborhood disadvantage to key health outcomes. Furthermore, given that the study population largely resides within the catchment area served by 2 tertiary care medical centers, the findings demonstrate that, even among patients living within close proximity to advanced medical care, neighborhood-level outcomes can differ systematically. Although the retrospective nature of this cohort limited our ability to draw definitive conclusions, we did find small differences in the rates of cardiac catheterization and subsequent revascularization (Table 1) between ADI ranking groups. Accordingly, health care organizations and policy makers should work to ensure that patients have not only equal access to comprehensive medical services but also equitable care and specialized services that help reduce these disparities in health outcomes. In addition, the study demonstrated the independent association of neighborhood socioeconomic factors with long-term cardiovascular outcomes in a cohort of individuals who experienced a first MI at a young age.

This study also has several limitations. First, patient addresses were collected from the electronic health data repository over the query period (August 1, 2016, to November 30, 2019). Although some patients may have changed addresses from the time of their MI to the query period, most patients who moved over the study period likely moved to socioeconomically similar neighborhoods.4 This presumption was supported by our analysis of 319 patients with more than 1 available home address that revealed little variability in neighborhood deprivation scores (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement). Second, as this was a retrospective cohort study, unmeasured and residual confounding may have been present even after extensive clinical adjustment.

Third, given that most of the patients lived in Massachusetts and that the 2 medical centers were located in 1 geographic region, the findings may be less generalizable to other areas or practice settings in the US. In particular, Massachusetts has a robust medical insurance safety net along with a health insurance mandate. Despite this reality, which would likely bias the findings toward the null, we still found a significant association between neighborhood deprivation and long-term mortality. We anticipate the findings to be amplified in other US states with a less robust social safety net.

Although we could not ascertain individual social risk factors, we were able to use a summary socioeconomic measure of the census block groups in which the patients lived. Neighborhood characteristics may be thought of as proxies for personal characteristics; they may also be conceptualized as independently conferring ecological risks and benefits on all who live there. For these reasons, measures like the ADI have been extensively used to characterize socioeconomic risk.4,6,13,23

Conclusions

Findings of this cohort study suggest that neighborhood and socioeconomic factors have a role in long-term post-MI survival among a young patient population, reinforcing the need for a better understanding of the association between socioeconomic disadvantage and poor outcomes in cardiovascular disease. The study also highlighted the need to identify patients who are living in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas and to establish robust post-MI outpatient care and comprehensive prevention strategies to reduce disparities in outcomes.

eAppendix 1. Definition of Risk Factors and Baseline Covariates

eAppendix 2. Patient Home Addresses: Additional Classification Details

eAppendix 3. Components of the Area Deprivation Index

eAppendix 4. Vital Status Determination

eAppendix 5. Medical Insurance Categorization

eAppendix 6. Sensitivity Analysis 1: Missing or Unclassified Insurance Data

eAppendix 7. Sensitivity Analysis 2: Massachusetts Resident Analysis

eAppendix 8. Additional Sensitivity Analyses With Alternate Multivariable Models

eAppendix 9. Temporal Trends of Myocardial Infarction

eAppendix 10. In-Hospital Deaths Stratified by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Insurance Classification

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Massachusetts Residency

eReferences

References

- 1.Shah NS, Lloyd-Jones DM, O’Flaherty M, et al. Trends in cardiometabolic mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(8):780-782. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Jaffe MG, et al. Recent trends in cardiovascular mortality in the United States and public health goals. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(5):594-599. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pahigiannis K, Thompson-Paul AM, Barfield W, et al. Progress toward improved cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2019;139(16):1957-1973. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diez Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99-106. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107123450205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1509-1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadhera RK, Wang Y, Figueroa JF, Dominici F, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. Mortality and hospitalizations for dually enrolled and nondually enrolled Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years or older, 2004 to 2017. JAMA. 2020;323(10):961-969. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233-1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Stroke Council . Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong G, Phillips SG, Hudson C, Curti D, Philips BU. Higher US rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2003-2010. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington RA, Califf RM, Balamurugan A, et al. Call to action: rural health: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Circulation. 2020;141(10):e615-e644. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh GK, Lin CC. Area deprivation and inequalities in health and health care outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(2):131-132. doi: 10.7326/M19-1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Increasing inequalities in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among US adults aged 25-64 years by area socioeconomic status, 1969-1998. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(3):600-613. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: a review of the literature. Circulation. 1993;88(4 Pt 1):1973-1998. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.4.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultz WM, Kelli HM, Lisko JC, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: challenges and interventions. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2166-2178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wall HK, Ritchey MD, Gillespie C, Omura JD, Jamal A, George MG. Vital signs: prevalence of key cardiovascular disease risk factors for million hearts 2022—United States, 2011-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(35):983-991. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6735a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666-668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angell SY, McConnell MV, Anderson CAM, et al. The American Heart Association 2030 Impact Goal: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e120-e138. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamad R, Penko J, Kazi DS, et al. Association of low socioeconomic status with premature coronary heart disease in US adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(8):899-908. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey. Accessed June 3, 2020. https://www.census.gov/history/www/programs/demographic/american_community_survey.html

- 23.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137-1143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ash AS, Mick EO, Ellis RP, Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Clark MA. Social determinants of health in managed care payment formulas. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1424-1430. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1013-1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jencks SF, Schuster A, Dougherty GB, Gerovich S, Brock JE, Kind AJH. Safety-net hospitals, neighborhood disadvantage, and readmissions under Maryland’s all-payer program: an observational study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(2):91-98. doi: 10.7326/M16-2671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making neighborhood-disadvantage metrics accessible—the neighborhood atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2456-2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadhera RK, Bhatt DL, Kind AJH, et al. Association of outpatient practice-level socioeconomic disadvantage with quality of care and outcomes among older adults with coronary artery disease: implications for value-based payment. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(4):e005977. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanaroff AC, Peterson ED, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Association of a P2Y12 inhibitor copayment reduction intervention with persistence and adherence with other secondary prevention medications: a post hoc analysis of the ARTEMIS cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(1):38-46. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Das SR, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence in adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States, 2013 to 2017. Circulation. 2019;140(25):2067-2075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldin J, Lurie IZ, McCubbin J. Health insurance and mortality: experimental evidence from taxpayer outreach. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. December 2019. Accessed May 25, 2020. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26533

- 32.Silverstein M, Hsu HE, Bell A. Addressing social determinants to improve population health: the balance between clinical care and public health. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2379-2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yurkovic A, Silverstein M, Bell A. Housing mobility and addressing social determinants of health within the health care system. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2082-2083. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh A, Collins B, Qamar A, et al. Study of young patients with myocardial infarction: design and rationale of the YOUNG-MI Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(11):955-961. doi: 10.1002/clc.22774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. ; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction; Authors/Task Force Members Chairpersons; Biomarker Subcommittee; ECG Subcommittee; Imaging Subcommittee; Classification Subcommittee; Intervention Subcommittee; Trials & Registries Subcommittee; Trials & Registries Subcommittee; Trials & Registries Subcommittee; Trials & Registries Subcommittee; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG); Document Reviewers . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1581-1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health . About the Area Deprivation Index v2.0. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.neighborhoodatlas.medicine.wisc.edu/

- 37.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(4):403-469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Lombard J, Rundek T, et al. Relationship of neighborhood greenness to heart disease in 249 405 US Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(6):e010258. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505-1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1224648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hajat A, Diez-Roux AV, Adar SD, et al. Air pollution and individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status: evidence from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(11-12):1325-1333. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diez Roux AV, Mujahid MS, Hirsch JA, Moore K, Moore LV. The impact of neighborhoods on CV risk. Glob Heart. 2016;11(3):353-363. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mensah GA. Socioeconomic status and heart health–time to tackle the gradient. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choudhry NK, Bykov K, Shrank WH, et al. Eliminating medication copayments reduces disparities in cardiovascular care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):863-870. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenkins KR, Ofstedal MB. The association between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk factors among middle-aged and older men and women. Women Health. 2014;54(1):15-34. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2013.858098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Bittner V, et al. ; WISE Investigators . Importance of socioeconomic status as a predictor of cardiovascular outcome and costs of care in women with suspected myocardial ischemia: results from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(7):1081-1092. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Backholer K, Peters SAE, Bots SH, Peeters A, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Sex differences in the relationship between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(6):550-557. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeFilippis EM, Collins BL, Singh A, et al. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI Registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(42):4127-4137. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Essien UR, Holmes DN, Jackson LR II, et al. Association of race/ethnicity with oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the outcomes registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation II. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(12):1174-1182. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(11):e006214. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nathan AS, Geng Z, Dayoub EJ, et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities in the prescription of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with venous thromboembolism in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(4):e005600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Rathore SS, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Racial differences in the use of cardiac catheterization after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(19):1443-1449. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson JB, Jackson LR II, Ugowe FE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in treatment and outcomes of severe aortic stenosis: a review. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(2):149-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.08.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618-626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Definition of Risk Factors and Baseline Covariates

eAppendix 2. Patient Home Addresses: Additional Classification Details

eAppendix 3. Components of the Area Deprivation Index

eAppendix 4. Vital Status Determination

eAppendix 5. Medical Insurance Categorization

eAppendix 6. Sensitivity Analysis 1: Missing or Unclassified Insurance Data

eAppendix 7. Sensitivity Analysis 2: Massachusetts Resident Analysis

eAppendix 8. Additional Sensitivity Analyses With Alternate Multivariable Models

eAppendix 9. Temporal Trends of Myocardial Infarction

eAppendix 10. In-Hospital Deaths Stratified by Grouping of Neighborhood Disadvantage

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Insurance Classification

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics by Massachusetts Residency

eReferences