Abstract

The European Parliament requested EFSA to develop a holistic risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees. To this end, a systems‐based approach that is composed of two core components: a monitoring system and a modelling system are put forward with honey bees taken as a showcase. Key developments in the current scientific opinion (including systematic data collection from sentinel beehives and an agent‐based simulation) have the potential to substantially contribute to future development of environmental risk assessments of multiple stressors at larger spatial and temporal scales. For the monitoring, sentinel hives would be placed across representative climatic zones and landscapes in the EU and connected to a platform for data storage and analysis. Data on bee health status, chemical residues and the immediate or broader landscape around the hives would be collected in a harmonised and standardised manner, and would be used to inform stakeholders, and the modelling system, ApisRAM, which simulates as accurately as possible a honey bee colony. ApisRAM would be calibrated and continuously updated with incoming monitoring data and emerging scientific knowledge from research. It will be a supportive tool for beekeeping, farming, research, risk assessment and risk management, and it will benefit the wider society. A societal outlook on the proposed approach is included and this was conducted with targeted social science research with 64 beekeepers from eight EU Member States and with members of the EU Bee Partnership. Gaps and opportunities are identified to further implement the approach. Conclusions and recommendations are made on a way forward, both for the application of the approach and its use in a broader context.

Keywords: agent‐based simulation, Apis mellifera, ApisRAM, bee biological agents, EU Bee Partnership, plant protection products, sentinel hives

Short abstract

This publication is linked to the following EFSA Supporting Publications articles: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/sp.efsa.2021.EN-6608/full

Summary

The introduction of this scientific opinion clarifies the background and Terms of Reference of this mandate (Section 1.1 ), but also provides background information on the MUST‐B project (‘EU efforts towards a holistic and integrated risk assessment approach of multiple stressors in bees’) and the EU Bee Partnership that are referred to in the mandate (Section 1.2 and Table 1 ) as well as to specific EU projects that are supporting MUST‐B (Appendix A ).

Table 1.

Overview of the key milestones achieved by EFSA in bee health, between 2012 and 2021

| Years | Key milestones (references) |

|---|---|

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2015 |

|

| 2016 |

|

| 2017 |

|

| 2018 |

|

| 2019 |

|

| 2020 |

|

| 2021 |

|

The Coordinators of the ENVI committee of the European Parliament endorsed a request for a scientific opinion by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) on the science behind the development of an integrated holistic approach for the risk assessment of multiple stressors in managed honey bees (Apis mellifera). This request is composed of four Terms of Reference. Three of them are focused on the development of a methodology that takes into account multiple stressors including single or multiple chemicals (i.e. coming from the environment, whether regulated or not; see Appendix B for clarifications of the terminology) and their various types of effects on bees (i.e. additive, synergistic, acute, chronic and sublethal). This development needs to include the work carried out by MUST‐B and the EFSA Scientific Panels. The last term of reference is on the EU Bee Partnership and the guidance needed for harmonised data collection.

The MUST‐B project is a multidisciplinary and multi‐annual scientific project that was initiated as a self‐task of the EFSA Scientific Committee and Emerging Risks Unit (Section 1.2.1 ). MUST‐B is composed of a task force represented by several units from ESFA's Scientific and Communication departments, four working groups (from the Scientific Committee and Emerging Risks Unit, the Animal Health and Welfare Unit, the Pesticides Unit and the Communication Unit), a discussion group of stakeholders called the ‘EU Bee Partnership’ (composed of representative stakeholders) and several outsourcing activities (i.e. risk factors analysis on EPILOBEE data set; chemical mixtures risk assessment in managed and wild bees; modelling development for an agent‐based honey bee colony model; field data collection to calibrate the honey bee colony model; and development of a prototype platform for the EU Bee Partnership to collect and exchange standardised data on bee health and beekeeping). Ongoing research projects such as ‘PoshBee’ and ‘B‐GOOD’ from Horizon 2020 support specifically the MUST‐B project and other EU‐funded projects such as ‘INSIGNIA’, ‘IoBee’ and ‘SAMS’ that are relevant to MUST‐B. Further description on these research projects is detailed in Appendix A . Data play a central role in MUST‐B, and the FAIR principles (findability, accessibility, interoperability, reusability) are very relevant. In addition, MUST‐B promotes data quality, reliability, openness and transparency, and supports stakeholder engagement to increase trust and evidence‐based risk assessment (Section 1.2.2 ). A willingness to increase trust is demonstrated by the shared goal of the EU Bee Partnership on the collection and sharing of harmonised data on bee health and beekeeping in Europe (Section 1.2.2 ).

The request from the European Parliament and the EFSA MUST‐B project fit into the actions and measures that were outlined in the European Green Deal for the European Union and its citizens. These specifically seek to make the EU's economy sustainable by supporting Member States to improve and restore damaged ecosystems, by promoting an environment that is free from pollution including multiple pollutants such as chemicals, by reducing the use and risk of chemical pesticides and by promoting data access and interoperability with the support of artificial intelligence and digitalisation (see Section 1.2.3 ).

In the interpretations of the Terms of Reference (Section 1.3 ), it is clarified that this scientific opinion presents ideas and concepts for consideration and future development. This opinion is aligned to aspirations outlined in the EU Green Deal and the prospective EFSA strategy 2027, presenting ideas and facilitating discussion, leading to practical solutions, in this critical area of environmental risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees. Further clarification of the terminologies used in the mandate and in this opinion is provided in Appendix B .

To contextualise the need for the development of a holistic and integrated environmental risk assessment approach for honey bees suffering exposure to multiple stressors, two overviews are provided in Section 2 . The first one on the regulatory background of the current framework for the environmental risk assessment of plant protection products (Section 2.1 ) and the second on the environmental risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees (Section 2.2.1 ) with insights into the challenges met (Section 2.2.2 ). Those challenges are linked to the complexity of a honey bee colony (Section 2.2.2.1 and Appendix C ) and to the landscape in which colonies are located (Section 2.2.2.2 ).

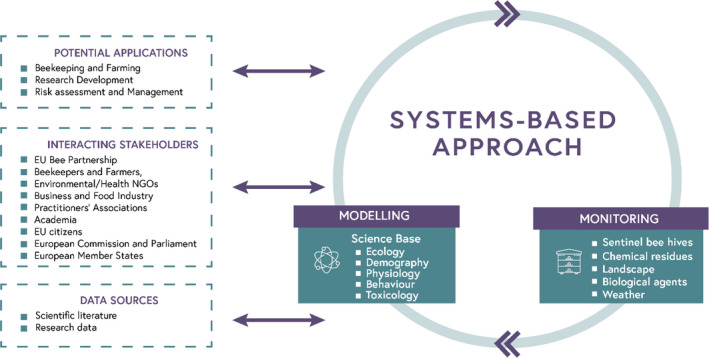

The proposed holistic and integrated environmental risk‐assessment approach for honey bees is based on a ‘systems‐based approach’ (Section 3.1 ), which has two core components linked by data flows (modelling and monitoring) and that is further developed in this scientific opinion (Section 3.2 ).

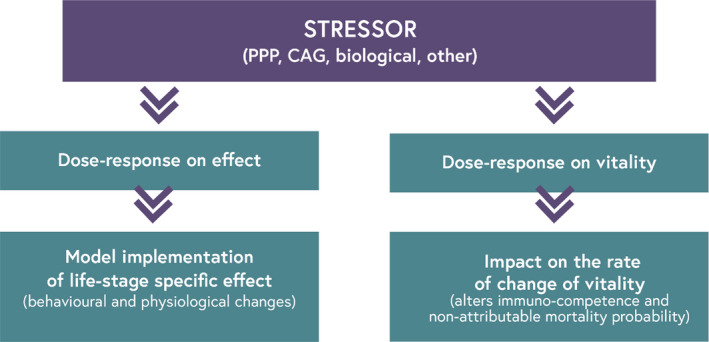

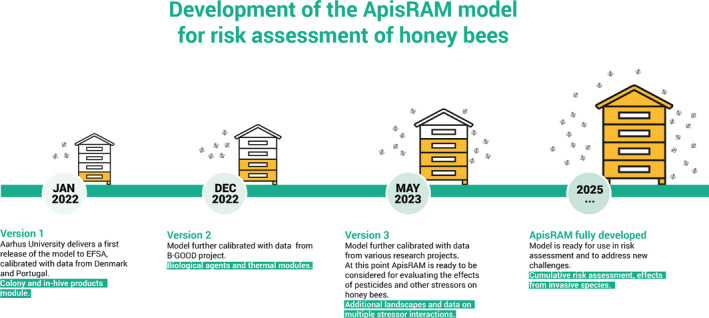

The modelling system is based on the development of ApisRAM, the agent‐based simulation model that EFSA has outsourced to assess either a single or two chemicals, including plant protection products, in interaction with other stressors such as biological agents (Varroa, Nosema, deformed wing virus and acute bee paralysis virus), beekeeping management practices and environmental factors relevant to the colony, including weather and floral resources (Section 3.2.1 ). This agent‐based simulation was formalised by the MUST‐B working group to address some shortcomings identified by EFSA when evaluating the usefulness of BEEHAVE as a regulatory tool (Section 3.2.1.1 ). ApisRAM is built in ALMaSS (an Animal, Landscape and Man Simulation System) with landscapes being simulated in substantial spatial detail (10 × 10 km area at a resolution of 1 m2) (Section 3.2.1.2 ). ApisRAM integrates multiple stressors (Section 3.2.1.3 ) and will also include sublethal effects such as reproductive performance of queens, development of hypopharyngeal glands and homing ability (Section 3.2.1.4 ). Any future development of ApisRAM will include the possibility to assess multiple chemicals (i.e. more than two compounds) and several other additional features, including several colonies, additional biological agents such as predators, nutrition quality and interaction with other stressors (see Section 3.2.1.5 ).

Regarding the monitoring system of the systems‐based approach, it will be composed of a network of sentinel hives located in various regions of Europe and connected to a platform for data storage and analysis (Section 3.2.2 ). Data will be collected to inform ApisRAM on the status of the honey bee colony. This will be defined by the HEALTHY‐B toolbox and indicators (Section 3.2.2.1 and Appendix D for a description of the (digital) tools to assess honey bee colony status). Additional data will be collected on exposure to chemical residues both inside and outside the sentinel hives (Section 3.2.2.2 ), and about the structure, management and dynamics of the landscapes, including around sentinel beehives (Section 3.2.2.3 ).

The systems‐based approach would have applications in, and potential benefit to, beekeeping, farming, research, risk assessment, risk management and the broader society (NGOs, Industry and EU citizens) (Section 4 ). As a tool for risk assessment and risk management, each of the following attributes is relevant: holistic, protective, integrative, adaptive, responsive, inclusionary, transparent and by being effectively communicated (Section 4.3 ).

A societal outlook on the systems‐based approach is included to understand and integrate the views of beekeepers and stakeholders (Section 5 and Appendices E and F ). Targeted research was conducted with beekeepers in selected EU countries to assess their views on the proposed approach, their needs and expectations in terms of data for managing their colonies, digital advancements and requirements for communication of applied research. Several stakeholders could interact with the system, including the members of the EU Bee Partnership, to promote accessible and reliable data collection and management. This systems‐based approach could contribute to risk assessment of bee health that is more open, transparent and trustworthy, contributing to the long‐term prosperity of honey bee colonies and beekeeping in Europe (Section 5.1 and Appendix E ). This work addresses the first term of reference of the mandate on the inclusion of beekeeping management practices in the development of a holistic risk assessment approach. In addition, interviews were conducted with members of the EU Bee Partnership to determine their perceived involvement and collaboration, the efficiency of the partnership, their views on harmonised data collection and sharing as well as the future involvement of new partners and the wider community of beekeepers (resources and coordination) (Section 5.2 and Appendix F ). This work is aligned to the Term of Reference on the need for guidance to the EU Bee Partnership on harmonised data collection and sharing in bee health and beekeeping in Europe. This work was also published as a standalone report, providing more details on the material, methodologies and results (EFSA, 2021).

The scientific opinion identified gaps and opportunities for the implementation of the systems‐based approach (Section 6 ). These related to environmental risk assessment, including the risk assessment of combined exposure to chemical mixtures (Section 6.1 ), the systems‐based approach (Section 6.2 ) comprising the modelling and monitoring (Section 6.2.1 ) and data flows into the systems‐based approach (Section 6.2.2 ).

Finally, conclusions and recommendations are made (Section 7 ). The importance of the socio‐political context (EU Green Deal) of this work was highlighted, as was the support of social sciences in facilitating exchanges with stakeholders in this opinion. This work goes beyond the ‘one substance approach’ by adopting a ‘systems‐based approach for a holistic and integrated risk assessment of multiple stressors’. The opinion highlights the importance of data in the systems‐based approach, and the spectrum of beneficiaries and players (Section 7.1 ). It was recommended that a systems‐based approach be introduced on a phased basis, seeking a more holistic and integrated environmental risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees. That is, from the simpler assessment of single substances through to the more complex assessment of multiple chemicals, landscape and indirect effects. Additional recommendations highlight the need for a more systematic inclusion of social sciences in EFSA's risk assessments to take into account stakeholders’ perspectives and make more fit‐for‐purpose risk assessments; the development of a Pan‐EU data collection effort through the sentinel hive network; the establishment of specific indicators of the health status of a honey bee colony, including the fine tuning of appropriate tools; and research investigations to fill the gaps in environmental risk assessment, model testing and data harmonisation. It is recommended that the systems‐based approach reports relevant information in a manner that gives EU citizens a better understanding of the possible causes and underlying mechanisms of bee health decline in Europe and worldwide. The proposed approach developed in this opinion on honey bees as a showcase could be used more broadly to advance environmental risk assessments (i.e. on other bee types, non‐target arthropods and other terrestrial or aquatic organisms) (Section 7.2 ).

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the European Parliament

On 28 June 2018, the Coordinators of the ENVI committee endorsed a request for a scientific opinion by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) on the science behind the development of an integrated and holistic approach for the risk assessment of multiple stressors in managed honey bees (Apis mellifera).

This request was submitted in accordance with Article 29 of Regulation (EC) No 178/20021 on ‘laying down the general principles and requirements of food law, setting up the European Food Safety Authority and laying down procedures in matters of food safety’, which provides that the European Parliament may request the Authority to issue a scientific opinion on matters falling within the Authority's mission.

The request was introduced taking into account the world‐wide importance of bees and pollinators, as 84% of plant species and 76% of Europe's food production depend on pollination by bees and this represents an estimated economic value of EUR14.2 billion a year. However, the health of honey bee colonies has been declining and there have been intensive scientific efforts to better understand the reasons for this decline, which may be related to intensive agriculture and pesticides use, poor bee nutrition, viruses and attacks by invasive species, as well as environmental changes and habitat loss.

The ENVI committee, therefore, considered it opportune for Parliament to request that EFSA deliver a scientific opinion on the science behind the development of an integrated and holistic approach for the risk assessment of multiple stressors in managed honey bees (Apis mellifera). The following issues have been identified for the development of a scientific opinion on the risk assessment of multiple stressors from both the in‐hive environment and the surrounding landscape:

The development of a methodology to take into account not only cumulative and synergistic effects of plant protection products (PPPs) but also include issues related to bees’ genetic variety, bee pathogens, bee management practices and the colony environment (Term of Reference ToR 1).

The assessment of acute and chronic effects of multiple stressors on honey bees including colony survival and sublethal effects (Term of Reference ToR 2).

The work being developed by stakeholders to achieve harmonised data collection and sharing on bee health in EU and, by doing so, support the EU Bee Partnership initiative by providing guidance for harmonised data collection and evidence‐based risk assessments (Term of Reference ToR 3).

The work conducted by EFSA under its project MUST‐B that integrates the work being developed in EFSA's various panels (Term of Reference ToR 4).

This scientific opinion, to be delivered by June 2021, should integrate efforts already conducted and propose a framework for risk assessment that can ensure the protection of managed honey bees in Europe.

1.2. The MUST‐B project

1.2.1. Activities within EFSA

Honey bee colony health decline finds its origin in a complex socioecological system. It can be considered as a multifactorial and multistakeholder issue given the number of factors and stressors that affect honey bee colony health, and the number of stakeholders who are involved. However, the current risk assessment approaches remain compartmentalised and intradisciplinary, and more holistic, multidisciplinary and integrated approaches are required to resolve such complexity.

At EFSA, a multidisciplinary task force was set up to move towards the development of such a transversal and holistic approach for the risk assessment of multiple stressors in bees. The task force published a review of the work carried out on bee health by EFSA, the European Member States (MS) and the European Commission (EFSA, 2012, 2014a). The task force highlighted knowledge gaps and research needs that would assist the development of a harmonised environmental risk assessment scheme for bees. This work was further discussed with stakeholders (EFSA, 2013a) and the European Commission (EFSA and European Commission Directorate‐General for Agriculture and Rural Development, 2016) to support EFSA's efforts to develop a holistic risk assessment for bees and to determine research priorities on bee health under the H2020 framework. In this context, two EU research calls were launched and granted in 2018 and 2019. The first project, ‘PoshBee’ (‘Pan‐European assessment, monitoring and mitigation of stressors on the health of bees’) (Appendix A ), should prove useful for the further implementation of this holistic risk assessment approach by gathering more evidence on exposure and risk characterisation of multiple chemicals for bee health, taking into account interactions with other stressors and factors in the environment of bees, such as biological stressors, nutrition and the broader environment (weather, climate and landscape characteristics). Within this project, it is intended to gather data on lethal, chronic and sublethal effects including toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics, full dose relationships and to develop new protocols and markers based on ‘omics (transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics) of chemical and biological stressors exposure/effects to be used in monitoring plans. The second project, ‘B‐GOOD’ (‘Giving beekeeping guidance by computational‐assisted decision making’) (Appendix A ), focuses on the development of ready‐to‐use tools for operationalising the ‘health status index’ developed by EFSA (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2016) to enable data collection and return to beekeepers, while exploring various socioeconomic and ecological factors beyond bee health. Within this project, the plan is to create an EU platform to collect and share knowledge, science and practice related to honey bees, their environment and agricultural and beekeeping practices. The ultimate project goal is to validate technologies for monitoring colonies and indicators of bee health in an automated or semi‐automated way to facilitate standardised and accurate data collection and transfer. In addition to these two research projects that specifically refer to MUST‐B, there is a third project that was initiated in 2018 called ‘INSIGNIA’ (‘A citizen science protocol for honey bee colony as bio‐sampler for pesticides’) which is building on the knowledge gained from the COLOSS Citizen Scientist Initiative (CSI) – Pollen project. This citizen science project (using beekeepers) will provide innovative methods to sample and analyse pesticides residues and botanical origin of the pollen brought back by foragers to the colony and determine pesticides exposure across various landscapes in EU (Appendix A ).

In parallel with the above research, which will generate data, tools and methodologies supporting EFSA's initial work in bee health, EFSA initiated a large 5‐year project in 2015 called ‘MUST‐B’ (‘EU efforts towards a holistic and integrated risk assessment approach of multiple stressors in bees’) to move further towards the development of a more holistic and integrated approach to the risk assessment of multiple stressors in bees, focusing to start with on honey bees.

MUST‐B was rooted in EFSA's strategic objectives 2020 (EFSA, 2015), in particular on the prioritisation of public and stakeholder engagement in the process of scientific assessment, on the widening of EFSA's evidence base, on the optimisation of access to its data and on preparing for future risk assessment challenges. MUST‐B focuses on three pillars: (i) the development of tools and methodologies for the risk assessment of multiple stressors in bees at the landscape level, (ii) gathering robust data (i.e. harmonised and standardised) for evidence‐based risk assessment of bee health and (iii) the engagement of stakeholders for harmonised data collection and data sharing in EU on bee health.

The MUST‐B working group has developed a framework incorporating modelling, experimental and field‐monitoring approaches. These complementary approaches are being combined to extrapolate risks from individual to colony levels, to assess the complexity of co‐exposures from multiple stressors coming from both the hive environment and the landscape and to determine their relative contribution to colony losses and weakening. Modelling is at the core of the MUST‐B framework with the development of a predictive agent‐based simulation of a honey bee colony, ‘ApisRAM’, in real Geographic Information System (GIS) landscapes and that is currently outsourced by EFSA. This computer simulation is being developed as a quantitative tool for regulatory risk‐assessment purposes and as a predictive and explanatory tool to better understand the (relative) risks and impacts of multiple stressors on honey bee colonies, including the overall complexity of interactions. The conceptual model (a qualitative description of the system to be modelled, including insights into the environmental and biological processes and their interactions and interdependencies) was defined by a group of experts, the MUST‐B working group (EFSA, 2016a,b), who took account of recommendations on the usefulness and suitability of an existing model, BEEHAVE (Becher et al., 2014), for use in a regulatory context (EFSA PPR Panel, 2015). The working group followed the EFSA scientific opinion on good modelling practices for model development and testing (EFSA PPR Panel, 2014). Criteria, derived based on minimum requirements, were described to design a field data collection to be conducted in the three EU regulatory zones to validate and calibrate the model as a regulatory tool for the risk assessment of PPPs in interaction with other stressors and factors such as biological stressors (Varroa destructor, Nosema spp. and their associated viruses, deformed wing virus (DWV) and acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV)), resources in the landscape, beekeeping management practices and weather conditions, on honey bee colonies (EFSA, 2017a,b). This is further described in Section 4.2 . EFSA outsourced the data collection in two EU MS, Denmark and Portugal (validating two EU zones, the north and the south). When designing the field data collection, the working group took into account lessons learnt from the EPILOBEE project (Laurent et al., 2016), a programme of active surveillance conducted across 17 EU MS during 2012–2014 (Jacques et al., 2016), in particular the lack of data on monitoring chemicals in contact with bees and bee products (e.g. PPP and veterinary products) and the importance of the preparatory phase for the fine tuning of field protocols, training field operators and setting a database to promote, as much as possible, automatic and harmonised entry and reduced field operator bias. In this exercise, the working group considered the work of the Healthy‐B working group (EFSA AHAW Panel, 2016) who developed a toolbox of methods and indicators to assess colony health in a standardised way across the EU.

In the Scientific Opinion and Guidance Document on the risk assessment of PPPs in bees (Apis mellifera, Bombus spp. and solitary bees) (EFSA PPR Panel, 2012; EFSA, 2013b), EFSA highlighted some shortcomings regarding semi‐field and field studies. An obvious one for field studies is the lack of control in exposure of bees that can forage freely over large areas in the landscape, usually beyond the limits of the tested plots and sometimes across (control and tested) plots and can be exposed not only to the single tested chemical but also to others present in the landscape. Another is the intrinsic variability between colonies and plots, leading to a much larger sampling size than currently used in regulatory tests to reach a meaningful statistical power. In addition, the methodologies and technologies used are not always adequate to detect chronic, small or sublethal effects and long‐term effects, which in time can become detrimental at the colony level. Finally, the spatial and temporal diversity of the agro‐environmental conditions in the EU may not be covered by the regulatory studies currently performed (European Parliament, 2018). This is further described in Section 2.2 .

ApisRAM is a honey bee colony model that has been developed in support of the MUST‐B work. It could be used in a range of different contexts including risk assessment (support to field testing) and research (e.g. to understand the relative importance of different stressors on colony weakening and losses). ApisRAM has been built in ALMaSS (Topping et al., 2003), which is an existing simulation system used to model human and other impacts on animals at landscape scales using detailed agent‐based simulation (ABS). ALMaSS has been used extensively in pesticide risk assessment, relevant to each of the following species: a carabid beetle Bembidion lampros (Topping et al., 2009; Topping and Lagisz, 2012; Topping et al., 2014; EFSA PPR Panel, 2015; Topping et al., 2015), the Eurasian skylark, Alauda arvensis (Odderskaer et al., 2003, 2004; Sibly et al., 2005; Topping et al., 2005; Topping et al., 2005; Jacobsen et al., 2008; Topping and Luttik, 2017), the European Brown Hare, Lepus europaeus (Topping et al., 2016; Topping and Weyman, 2018), the field vole, Microtus agrestis (Topping et al., 2008; Dalkvist et al., 2009; Dalkvist et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2016), the linyphiid spider, Erigone atra (Thorbek and Topping, 2005; Topping et al., 2014) and the rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus (Topping and Weyman, 2018). In each case, ALMaSS includes a landscape model as an environment into which an animal model is placed (Topping et al., 2003).

The current project, as a show case, is focused on honey bees. However, key developments in the current scientific opinion (including systematic data collection from sentinel beehives and agent‐based modelling) have the potential to substantially contribute to the future development of risk assessments of multiple stressors in other organisms at larger spatial and temporal scales.

An overview of the activities conducted at EFSA on bee health, including the MUST‐B project is provided in Table 1.

1.2.2. The EU Bee Partnership

Since 2012, the European Parliament has coordinated the activities of the European Week of Bees and Pollination comprising a high‐level conference and a scientific symposium with beekeepers. Conscious that bee mortality observed across the world was likely to be due to a number of factors, stakeholders involved in EU Bee Week activities have stressed the need for better collaboration between all interested parties through greater dialogue. They have also called for the establishment of an operational technical platform to improve exchanges between beekeepers and scientists.

In 2017, the European Parliament's Apiculture and Bee Health Working Group tasked EFSA with coordinating the Bee Week's scientific symposium with a focus on the collection and sharing of harmonised bee health data in Europe. The event brought together around 130 stakeholders (i.e. beekeepers, farmers, industry, scientists, risk assessors and managers, the public and policy makers), and ended with a general agreement among all representative stakeholders to work towards setting up an EU Bee Partnership (EUBP). This Partnership has been facilitated by EFSA, and the European Commission (DG AGRI, SANTE, ENV, RTD, CONNECT) (EFSA, 2017a,b) has also participated. Further to recommendations by stakeholders, EFSA supported the establishment of a discussion group composed of representative stakeholders to define the Terms of Reference (ToR) of the EUBP (EFSA, 2018a). Progress has been reported back to the annual European Parliament Bee Week High Level Conference.

This 2017 event highlighted the need for harmonising data collection and collaborations across all involved stakeholders, underpinning improvements to the sharing, analysis and management of data on bee health throughout EU (EFSA, 2017a,b). Data standardisation was discussed, including the development of a common format (data models) and a common representation (terminologies, vocabularies, coding schemes). EFSA had prior expertise in this area, having developed harmonised and standardised field data collection to assess bee health (e.g. the Standard Sample Description for Food and Feed version 2.0, SSD2; DATA Unit, 2017) for the calibration and validation of the ApisRAM model (EFSA, 2013c) (see Appendix A in EFSA, 2017a,b). At this event, the need for increased data quality and reliability (with quality controls in place) was also emphasised, including electronic capture of data from laboratory information management systems and digital hives (e.g. hive sensors, hive scales, weather stations, etc.). These data need to be validated with proper business rules following the EFSA Guidance on Data Exchange version 2.0 (EFSA, 2014b) to ensure transparency and openness regarding the way in which the data are collected and analysed. A final theme of discussion was the need for efficient data exchange using specific files format for data transmission. In the beekeeping community, the XML standard for exchange about bees and beekeeping data and information (Cazier et al., 2018; Haefeker, 2018) was adopted by the EUBP when developing a prototype platform for harmonised data exchange in EU on bee health and beekeeping.

In 2019, with the knowledge gained from IoBee (Appendix A ), a European‐funded Fast‐Track‐to‐Innovation project coordinated by BeeLife, a proof of concept (PoC) was developed for the EUBP platform to store, exchange and analyse data from different sources on bee health. The PoC uses XML format for data interoperability, a standard that was endorsed by the EUBP as a self‐describing data format that can allow data exchange.

In 2020, EFSA supported the EUBP in developing the PoC into a prototype platform. This prototype forms the basis for an operational platform to be further developed and that would integrate all relevant information, knowledge and data to be collected by, and exchanged among, stakeholders on bee health and beekeeping. This operational platform would make relevant data accessible to end users such as beekeepers, beekeeping or farming associations, researchers, agencies and policymakers. The platform will ultimately be expanded to include other bee species and more widely to other pollinators both within and outside EU, where cheap and easy‐to‐use open source Information and Communications Technology (ICT) applications are being developed (e.g. see SAMS project in Appendix A ).

The ambition to develop the operational platform in the future to include data on wild bees (i.e. bumblebees and solitary bees) and other pollinators could lead to a number of synergies with the European Commission's EU Pollinators Initiative.

1.2.3. In the context of the EU Green Deal

In December 2019, the European Commission set out the European Green Deal for the European Union and its citizens to make the EU economy sustainable by turning climate and environmental challenges into opportunities (European Commission, 2019a). For this purpose, a new paradigm and specific Sustainable Development Goals were defined (European Commission, 2019b) with a roadmap of key actions and measures, including legislative ones, to achieve these goals, to be undertaken between 2020 and 2021 (European Commission, 2019c).

Many of these actions and measures are particularly relevant to the overall approach that has been developed under MUST‐B, including:

helping MSs to improve and restore damaged ecosystems by addressing the main drivers of biodiversity loss;

promoting a toxic‐free environment through better monitoring, reporting, preventing and remedying pollution and addressing combined effects from multiple pollutants (e.g. multiple chemicals);

significantly reducing the use and risk of chemical pesticides by encouraging innovation for the development of safe and sustainable alternatives;

promoting data access and interoperability with innovation, e.g. digitalisation and artificial intelligence for evidence‐based decisions regarding environmental challenges.

1.3. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

This scientific opinion presents ideas and concepts for consideration and future development. The document is not prescriptive, nor is it constrained by or aligned to specific EU legislation. Rather, the opinion seeks to present a framework, and supporting rationale, that is robust and forward thinking, while acknowledging that some detail will require further elaboration, which in part will be reliant on new scientific discoveries. This scientific opinion is aligned to aspirations outlined in the EU Green Deal and the EFSA Strategy 2027 (EFSA, 2019a,b,c), presenting ideas and facilitating discussion, leading to practical solutions in this critical area of environmental risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees.

The ToR 1 and ToR 2 refer to the development of a holistic and integrated risk assessment methodology taking into account various factors (i.e. ‘bee genetic diversity’, ‘beekeeping management practices’, ‘resource providing unit’) and stressors (‘chemical’ and ‘biological’) as well as various effect types (‘acute’, ‘chronic’, ‘sublethal’, ‘cumulative’, ‘synergistic’, ‘antagonistic’) on colony health status. For one colony, this would mean an adequate size, demographic structure and behaviour; an adequate production of bee products (both in relation to the annual life cycle of the colony and the geographical location); and provision of pollination services (see Section 3.2.2.1 ). ToR 1 refers to ‘PPPs’ and ‘cumulative effects’. Clarifications on the definitions of those terms (i.e. ‘PPPs’ and ‘cumulative effects’) are provided in Appendix B . In their environment, bees are exposed to PPPs as well as other chemicals (e.g. biocides, veterinary products and contaminants), which are referred to in this scientific opinion as ‘multiple chemicals’ or ‘chemical stressors’. The term ‘cumulative effects’ is functionally synonymous to ‘cumulative impacts’ and frequently used in the area of environmental impact assessment under Annex IV of the Directive 2011/92/EU2 (see Appendix B for more details). In the context of this scientific opinion, which is focused on environmental risk assessment of multiple chemicals and stressors in honey bees, ‘cumulative effects’ refer to ‘combined effects from exposure to multiple chemicals’ at a given time (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2019) or to ‘combined effects from exposure to multiple chemicals and/or other multiple stressors’ at a single or multiple time points. E.g. foragers might be exposed in time and space to several and different types of stressors, resulting in complex (non‐linear) responses at the colony level.

To address these two ToRs, an integrated and holistic approach is presented in Section 3.1 ‘A proposal for a systems‐based approach to multiple stressors in honey bees. Findings from social research have informed the holistic approach by providing an understanding of the perspectives of the interested parties (e.g. beekeepers). This is further developed under Section 5.1 in which targeted research was conducted among beekeepers in EU to assess their understanding of the proposed approach, their needs and expectations in terms of data for managing their colonies, digital advancements and requirements for communication of applied research.

Furthermore, methodologies for risk assessment sought in ToR 1 and ToR 2 are addressed under Section 3.2 ‘the core components of the systems‐based approach’ and some clarifications on the terminology used under these ToRs are provided by the working group (Appendix B ). The proposed approach is in line with the recommendations for actions made under the EU Green Deal (see Section 1.2.3 ) and is based on the work achieved under the auspice of the MUST‐B project (see Section 1.2.1 ) and the knowledge gained on the risk assessment of combined exposure to multiple chemicals (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2019) applied to honey bee colonies (Spurgeon et al., 2016).

The third term of reference (ToR 3) refers to harmonised data collection and sharing among stakeholders as developed by the EUBP, which has the goal to improve data collection, management, sharing and communications to achieve a holistic assessment of bee health in EU and beyond (see Sections 1.2.1 and 1.2.2 ). EFSA supports this initiative which is aligned to its mission to facilitate discussion among stakeholders, by providing guidance for harmonised data collection in the context of bee health assessment (Jacques et al., 2016, 2017; EFSA, 2017a,b) and by promoting research in this field (EFSA, 2014a; EFSA and European Commission's Directorate‐General for Agriculture and Rural Development, 2016), with the support of developments under the research framework H2020. This Term of Reference (ToR 3) is addressed under Section 5.2 and supported by feedback obtained from members of the EUBP.

The inclusion of the need to take into account beekeeping management practices in the Terms of Reference of the request (ToR 1), as well as the work being developed to achieve harmonised data collection (ToR 3), have prompted EFSA to bring social science skills to the interdisciplinary mix of expertise working together on this project. In line with EFSA's social science roadmap, targeted social research was commissioned to provide an understanding of the perspectives of the interested parties and thus strengthen engagement and communication with target audiences.

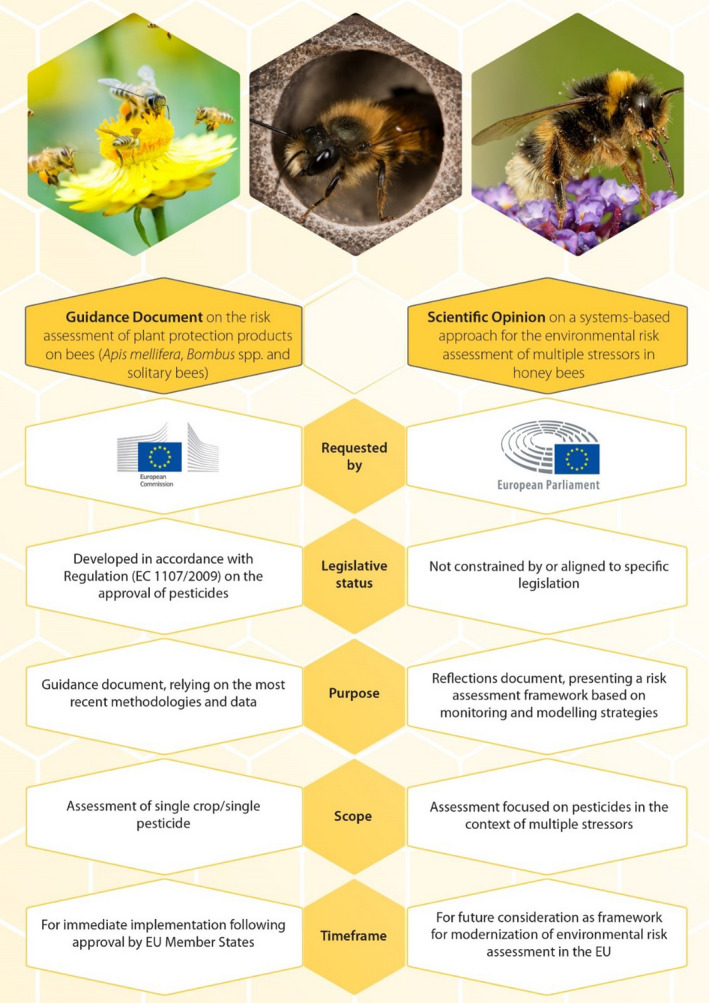

The ToR 4 is on the inclusion of EFSA's work on bee health through the MUST‐B project. As highlighted in Section 1.2.1 and Table 1 , MUST‐B is rooted in EFSA's work, through the multidisciplinary Bee Task Force representing all Panels and Units involved in bee health (EFSA, 2012). This work is based on stakeholder engagement for a participative, inclusionary and integrated approach to environmental risk assessment, taking into account multiple chemical and biological stressors and combining modelling and monitoring strategies. This work might provide additional lines of evidence to risk assessors and may already have been implemented as part of the current predictive risk assessment that is under review through the EFSA Bee Guidance on the risk assessment of PPPs in bees (EFSA, in preparation). The main differences between the Guidance Document and this Scientific Opinion in terms of requestor, legislative status, purpose, scope and timeframe are summarised below (Figure 1). However, beyond those differences, the two documents each contribute, within their respective remits, to the future of environmental risk assessment (More et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Main differences, in terms of requestor, legislative status, purpose, scope and timeframe, between the Guidance Document (the reviewed guidance document on the risk assessment of PPPs in bees; EFSA, in preparation) and this Scientific Opinion (on the systems‐based approach for the ERA of multiples stressors in honey bees) (figure from More et al. (2021))

Finally, a description of the terms in the mandate that require clarification to avoid any misinterpretation is presented in Appendix B . In addition, a glossary of the widely used terms and concepts in the multiple‐stressor research (e.g. ‘multiple‐stressor’, ‘cumulative effect’, ‘stressor interaction’, ‘additive’, ‘antagonist’) is provided by Orr et al. (2020).

2. The need for a holistic and integrated approach to the environmental risk assessment for honey bees

2.1. Environmental risk assessment of PPPs

The EU legal framework regarding placing on the market of PPPs (i.e. Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093) provides for a two‐phase procedure before they can be placed on the market: an EU‐level approval of the active substance used in PPPs and a national level authorisation of the PPPs. Directive 2009/128/EC4 (the Sustainable Use Directive) sets up a framework to achieve the sustainable use of pesticides. Any actions for PPP risk reductions, including some mitigation measures, belong to this Directive.

An environmental risk assessment of PPPs is required under Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093 to demonstrate that residues of a PPP, following its use according to good agricultural practices, under realistic conditions of use, does not pose any unacceptable effect on the environment. For the risk assessment for bees, a guidance document was developed by EFSA (EFSA, 2013b) and is currently under review (EFSA, in preparation). This guidance includes recommendations for conducting the risk assessment for bees (honey bees, bumble bees and solitary bees) that are exposed to residues of a PPP and its metabolites. In particular, the document provides guidance on how the exposure estimation for a specific use can be performed by considering the various routes of exposure (oral uptake of contaminated pollen/nectar and contact exposure) and the various sources of exposure. The document also outlines how the hazard characterisation will be conducted by considering acute, chronic, sublethal and accumulative effects. The risk assessment, based on the exposure and hazard characterisation, seeks to demonstrate whether the PPP under evaluation and its use have an unacceptable effect on bees (namely ‘has no unacceptable acute or chronic effects on colony survival and development, taking into account effects on honey bee larvae and honey bee behaviour’). Operationally, this is demonstrated by compliance of the risk assessments with the specific protection goals defined by the risk managers. The risk assessment of mixtures of PPPs regarding formulations or preparations that contain at least one active substance (see Appendix B for further definitions) is part of the evaluation of a PPP under Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093, and it is also covered by the EFSA Guidance Document (EFSA, 2013b).

Recently, EFSA published the MIXTOX Guidance on ‘harmonised methods for human health, animal health and ecological risk assessment of combined exposure to multiple chemicals’. MIXTOX provides stepwise approaches for problem formulation and for each step of the risk assessment process, i.e. exposure assessment, hazard assessment and risk characterisation using whole mixture and component‐based approaches as well as a reporting table to summarise the outcome of the risk assessment (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2019). This Guidance is relevant to bee health risk assessment of multiple chemicals (PPPs, biocides, veterinary products and contaminants) and provides an example to investigate combined toxicity in honey bees, regarding interactions between multiple chemicals, using component‐based approaches. In addition, these methodologies have been further adapted to the risk assessment of multiple stressors in a honey bee colony using the ApisRAM model (Sections 3.2.1.3 and 3.2.1.5 ). It is foreseen that these methodologies provide further opportunities to develop fit‐for‐purpose environmental risk assessment approaches for single and multiple PPPs applied at the same time, or in the same crops/fields applied at different time points, on bees. Indeed, the co‐exposure of honey bee colonies with multiple PPPs is the result of the complexity of landscapes, but also of the succession of crops on the same plot, taking into account the persistence of PPPs in the environment. With the complexity of the landscapes, this implies to consider the mobility of PPPs in the environment, especially by surface water and potential drift from spray applications. Co‐exposure to bees can also be explained by the large surface areas foraged by bees and the accumulation of residues in the hive (pollen/beebread, nectar/honey and wax).

Of all the areas in EFSA's remit that could contribute to the EU Green Deal, advancing the environmental risk assessment of PPPs is expected to have the highest possible impact. Although Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093 and the Sustainable Use Directive provide a robust framework for the environmental risk assessment of PPPs, several improvements are demanded by recent scientific evidence, increasingly complex environmental challenges and evolving societal concerns. The opportunity for enhancing the environmental risk assessment of PPPs is also driven by: (1) the new EFSA mandate given by the transparency regulation (EU) 2019/13815; and (2) European Commission's REFIT process of the Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093 (Group of Chief Scientific Advisers, 2018).

2.2. Environmental risk assessment of multiple stressors in honey bees

2.2.1. Overview

Managed colonies of honey bees (Apis mellifera spp.) represent an important source of goods and income. For the honey market, while Europe is the second world producer (2,80,000 tons), it is only 60% self‐sufficient in honey (European Commission, 2020a,b). Further, honey bee colony losses are reported globally, and particular in Europe and North America, reaching high mortality rates of about 30% (Laurent et al., 2016; Steinhauer et al., 2014). Such mortality rates are not specific to honey bee populations, but also affect other bee species, insects and biodiversity more widely (Potts et al., 2010; Dirzo et al., 2014; Hallmann et al., 2017; Wagner, 2019; Skarbek et al., 2021). Such concerns have been raised in the context of inefficiencies in the current environmental risk assessment framework (EFSA, 2012; Brühl and Zaller, 2019; Sgolastra et al., 2020; Topping et al., 2020).

Building on this body of evidence, there are several key issues related to bee health risk assessment of multiple chemicals and stressors, and broadly speaking for terrestrial organisms, that need to be addressed:

The environmental risk assessment of regulated products (e.g. PPPs, biocides, veterinary products) is following the ‘one substance’ approach even though data on formulations with multiple active substances are reviewed for the registration of formulated products (see previous Section 2.1). Further work is needed to take account of current practices that lead to the co‐occurrence, co‐exposure and potential combined effects (additive, synergistic or antagonistic) of multiple chemicals on organisms through time. E.g. current farming practices can lead to mixture applications (Fryday et al., 2011), multiple applications to single crops (Garthwaite et al., 2015; Luttik et al., 2017) and also the application of veterinary products inside the hives (Mullin et al., 2010; Lozano et al., 2019).

The risk assessments of regulated chemical products need to be conducted in the context of multiple stressors such as non‐regulated chemicals, biological agents and beekeeping management practices and potentially impacted by habitat, weather and climate.

There is a need for a link between the temporal dynamics of the exposed populations in the landscape and the desired level of protection of the organisms. A proper hazard and exposure assessment should be developed enabling a spatio‐temporal landscape for environmental risk assessment to be performed. E.g. given the lifespan of worker bees (~ 40 days, during the foraging season, approximately from spring to autumn), and an awareness that bees and their colonies can be continuously exposed to chemicals throughout all the beekeeping seasons (Tosi et al., 2018), a longer chronic timeframe would be more realistic to allow chronic lethal and sublethal effects occurring beyond 10‐days to be captured (OECD, 2017; Simon‐Delso et al., 2018; Tosi et al., in press).

There is a requirement for evidence regarding species‐specific traits in relation to chemical toxicity, in particular for surrogate species used to cover main taxa/guilds.

Sublethal effects are not fully addressed by the current regulatory risk assessment schemes because of the lack of knowledge of such effects on individual bees and at the colony level (for social bees such as honey bees) over a range of time scales, from relatively short to long (i.e. from a few hours to a few months).

Indirect effects that have been recognised as significant at the ecosystem level (e.g. effects on pollination services) are currently not accounted for.

A scientific rationale is needed for the derivation of assessment factors taking into account variability and uncertainty about extrapolations from laboratory experiments to field trials. While representativeness is higher in field than laboratory conditions, variability and uncertainty are likely higher in the field because of the foraging range of the bees (which covers larger surface areas than those covered in the higher tier studies, leading to underestimating the foragers’ exposure).

Context dependency should be addressed to quantify exposure and susceptibility at individual and population levels, considering both regulated and non‐regulated stressors. Furthermore, there is a scientific need for more data on realistic, context‐specific risk assessment scenarios, reflecting the choice and importance of landscape management, and the timing and frequency of PPPs (Topping et al., 2016).

Data gaps on pre‐existing conditions related to habitat, nutritional status as well as effects from other stressors on bee populations need to be filled. Such pre‐existing conditions might be the result of several carry over effects, as seen with pollen scarcity that influence colony development over the longer term (Requier et al., 2016) and therefore, long‐term monitoring will be needed to cover such effects.

There is limited quantitative information on the actual exposure and toxicity (including colony recovery and resilience) of pesticides in honey bees.

2.2.2. Current challenges to honey bee health risk assessment

There is a series of challenges faced with the risk assessment of PPPs for honey bee colony health in the context of multiple stressors. In particular, risk assessments need to consider:

-

The biological complexity of the honey bee colony, the role of individuals within the superorganism, the reliance on appropriate behaviours of many individual bees on the proper functioning and health of the colony and the factors that influence colony dynamics (noting that the current risk assessment guidelines cannot capture the complexity of the dynamics of a superorganism):

-

–

The challenge in seeking to connect individual bee responses to colony‐level impact.

-

–

The challenge in linking the specific protection goals to sublethal endpoints that affect individual bees and in turn the colony that is functioning as a superorganism.

-

–

The challenges faced in risk assessment, including multiple routes of exposure (i.e. acute vs. chronic, oral vs. contact), co‐exposure to multiple chemicals, delayed exposure through honey stores and comb wax and variability of chemical toxicity in relation to multiple factors (such as seasonality, bee age, bee genetics).

-

–

The genetic diversity of honey bees, including variations within and between colonies and between the subspecies present in EU that may be sufficient to influence a risk assessment.

-

–

-

The complex landscape in which the colony is situated and foraging, with implications for many aspects of the risk assessment, including PPP co‐exposure:

-

–

The temporal co‐occurrence of multiple stressors.

-

–

The spatial scale affecting potential recovery.

-

–

The interactions that occurs between these stressors (both regulated and non‐regulated).

-

–

Indirect effects due to loss in food/habitat.

-

–

Although many of these issues are relevant to environmental risk assessment more broadly, honey bee risk assessment presents several particular challenges that are considered further in Sections 2.2.2.1 and 2.2.2.2 . As examples, honey bee colonies are superorganisms with complex feedback loops, buffering effects and emergent properties. Stressor effects occur at the level of the individual bee, indirectly leading to effects at the colony level that can be difficult to predict. Environmental risk assessment in mammals and birds (EFSA, 2009) is conducted at the level of the individual for the acute effects and at the level of the population for the long‐term effects. In non‐target arthropods, the risk assessment is conducted at the level of the population (EFSA PPR Panel, 2014). Furthermore, foraging from a single honey bee colony can occur over a landscape that is both large (e.g. for a foraging distance of 5 km, the foraged surface area goes up to 80 km2) and complex, with the potential for combined exposure of the colony to multiple chemicals and other stressors. The complexity of landscapes varies in different agricultural contexts, from homogeneous (e.g. intensive agriculture presenting less diverse floral resources) to more heterogeneous (e.g. mixed cropping systems presenting more diverse floral resources and non‐cultivated areas such as gardens, field edges, roadside areas (ditchbanks, streambanks), urban/suburban lands, etc.).

2.2.2.1. The complexity of a honey bee colony

Honey bee colonies are biologically complex. Each colony is comprised of one fertile female queen, tens of thousands of unfertile female workers and hundreds of fertile male drones (Winston, 1987). Honey bees are eusocial insects, and colonies are characterised by cooperative brood care, overlapping generations within a colony of adults and a division of labour into reproductive and non‐reproductive groups (Seeley, 1985; Winston, 1987). The individuals have differing life stages, with differing diets and energy requirements across these life stages and castes (Michener, 1974). Although each individual has specialised tasks (nursing, foraging, etc.), the colony members work cooperatively as a ‘superorganism’ to support functions that are comparable with those of cells in a multicellular organism (Wilson and Sober, 1989; Moritz and Southwick, 1992; Page et al., 2016). The proper functioning and health of the colony is reliant on the appropriate behaviours of many individual bees.

The dynamics of honey bee colonies is influenced by a range of factors, given that the colony (e.g. demographic status) interacts closely with its environment (e.g. resource availability, weather conditions). As a result, the egg‐laying rate of the queen, a primary driver of colony dynamics, will be influenced by key feedback loops, including those between colony demography, colony size and egg laying. The number of nurse bees and food influx (from the environment) will each affect egg laying and brood survival, and hence the future colony structure (Robinson, 1992; Becher et al., 2013). A colony is able to control the ratio of in‐hive and forager bees through mechanisms of social feedback (Russell et al., 2013).

From individuals to colony effects

A key feature of honey bee colonies, as with other superorganisms, is the development of emergent properties, these being properties that emerge within a system that are different from those of the components (i.e. individual bees) that make up the system (Seeley, 1989; Wilson and Sober, 1989; Moritz and Southwick, 1992). Emergent system properties (e.g. colony size, brood production) are a function of long‐causal chains and feedback loops (positive and negative) between the interacting bees and their local environment. Examples of these emergent properties include thermoregulation (which is considered in further detail here), initiation of comb construction and colony population dynamics.

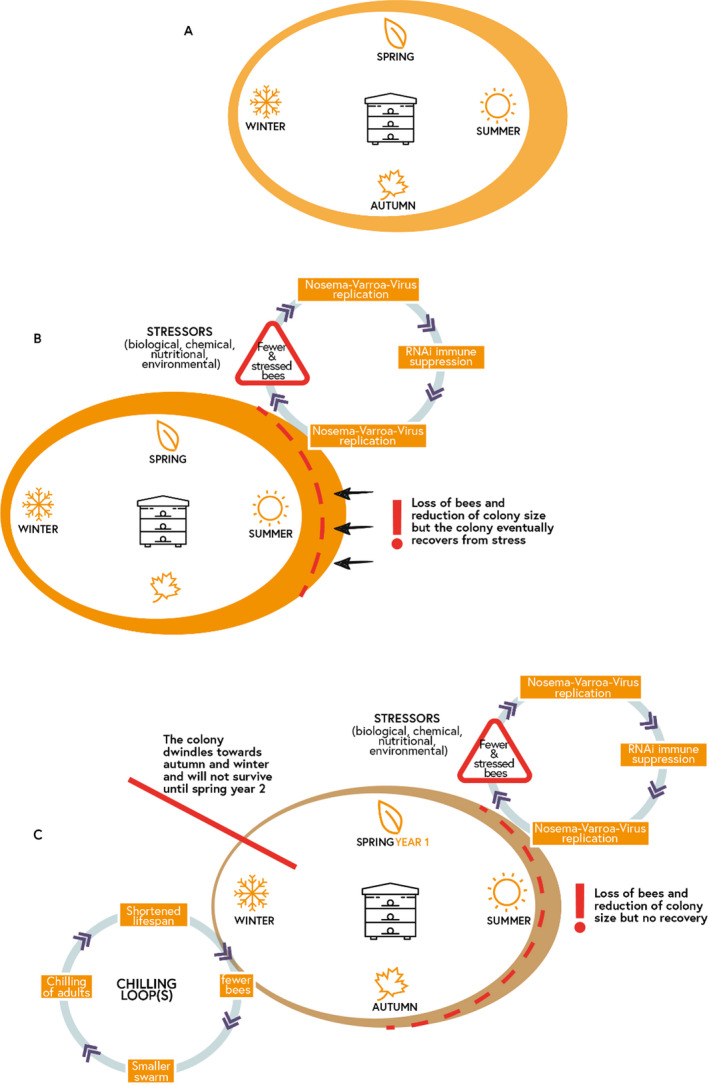

Thermoregulation of a colony is achieved through the actions of bees responding to temperature conditions in their immediate vicinity. As temperatures fall, bees cluster together with heat being generated by mature bees by shivering their flight muscles. Younger bees, which cannot generate heat in this way, are found at the centre of the cluster. In response to the surrounding environment, therefore, worker bees can warm up or cool the colony and brood combs by various mechanisms such as shielding and fanning (Stabentheiner et al., 2010). Thermoregulation in honey bee colonies is costly in terms of energy budget, particularly during the winter (EFSA PPR Panel, 2012). In addition, in Europe, winter mortalities in honey bee colonies are of concern (Laurent et al., 2016). A hypothetical and explanatory scenario was made to describe the possible complex mechanisms from the individual to colony level behind such mortalities (Figure 2). The example used the context of exposure to multiple stressors and included a failure in thermoregulation (Figure 2). These processes demonstrate the various mechanisms by which a colony may lose individual bees from spring to autumn (via intoxication and infection loops) and result in a colony of bees that is not large enough to thermoregulate efficiently in winter (first chilling loop), which in turn may lead to a much smaller swarm (second chilling loop; step 4) and ultimately lead to the loss of the colony. There could be several chilling loops by which the colony loses bees more or less rapidly over time, depending on the strength of the colony before wintering (initial population size).

Figure 2.

Development and size of a colony under different situations: from an average colony maintained by good beekeeping practices (A) and from a robust or weak colony (B and C, respectively). Exposure to chemical, biological and/or nutritional (i.e. food quality and quantity) stressors leads to either recovery (B) or winter colony mortality (C)

This example of emergent effects highlights the complex relationship between individual bees and colony effects. Responses are multifaceted and occur at different levels: at the level of the individual (e.g. thermoregulating bees, wax‐producing bees, nursing bees, foraging bees); at the level of the process (with associated feedback loops) (e.g. production of heat or ventilation, production of wax, egg laying and brood care); and through emergent properties (e.g. thermoregulation, comb construction, colony population dynamics). Furthermore, these systems are complex and adaptive (sensu Holland, 2006), and stressors can be multiple and interacting. The various internal and external aspects of a colony interact dynamically in both space and time and are composed of many components interacting with each other in non‐linear ways, including learning. In summary, therefore, the link between these factors and overall colony behaviour and characteristics is not simple, with the potential for an apparent disconnection between individual responses and colony effects.

Stressors that do not lead to direct mortality of individual bees can still substantially and adversely affect colony health. E.g. Varroa destructor, a parasitic mite that feeds on honey bees represents a major threat for the colonies (Bailey and Ball, 1991). Another example is neonicotinoid pesticides which can impair forager flight, locomotion, navigation and orientation (Tison et al., 2016; Tosi and Nieh, 2017; Tosi et al., 2017b), leading to a significant reduction in the number of foragers returning to the nest after a day's activity (Henry et al., 2012). In response, there are short‐term compensatory effects at a colony level, but at a cost to the colony. Nurse bees are assigned to forage at an earlier age, and drone brood production is delayed in favour of increased worker brood production (Henry et al., 2015). In the long term, however, adverse colony impacts can be substantial, leading to significantly reduced adult bee populations, a decrease in brood surface areas and average frame weights and reduced in‐hive temperature control (Meikle et al., 2016; Tsvetkov et al., 2017). As one example, in the mid and long term for the bee population in a given area, the reduction in the number of males produced could affect the fertilisation of the virgin queens, with possible negative consequences on the dynamics of bee populations in this area. Indeed, queens artificially inseminated with a smaller quantity of semen than normal present physiological disorders and exhibited lower rates of overwintering survival than normal (see the review by Brutscher et al., 2019).

Importance of sublethal effects for bee colony health

There is increasing evidence of adverse impacts on honey bee colony health from sublethal effects that may translate into lethal effects, including those affecting communication (Eiri and Nieh, 2012), memory (Decourtye et al., 2005), navigation/orientation (Fischer et al., 2014; Henry et al., 2015; Tison et al., 2016), locomotion such as bee activity and motor functions (Tosi and Nieh, 2017; Wu et al., 2017), thermoregulation (Vandame and Belzunces, 1998; Tosi et al., 2016), reproduction (Wu‐Smart and Spivak, 2016), development (i.e. HPGs) (Hatjina et al., 2013), social immunity (Brandt et al., 2016), food consumption (Blacquiere et al., 2012; Tosi and Nieh, 2017) and preference (Kessler et al., 2015), phototaxis (Tosi and Nieh, 2017) and detoxification (Han et al., 2018; Tarek et al., 2018). Some authors have highlighted the impact of sublethal effects (Desneux et al., 2007) on colony health when bees are exposed to neonicotinoids (e.g. Pisa et al., 2015; Meikle et al., 2016; Wu‐Smart and Spivak, 2016; Pisa et al., 2017), sulfoximine (Siviter et al., 2018) and butenolide (Tosi and Nieh, 2019) insecticides. While pesticides are the most studied factor to cause sublethal effects on honey bees (Thompson, 2012; ANSES, 2015), other stressors may be involved.

These studies highlighted the need to capture sublethal effects which, at the time of writing, are currently not considered in environmental risk assessment, and to link sublethal effects to specific protection goals (SPGs). The association between sublethal effects (measured at the level of the individual) and SPGs (defined at the level of the colony) has not previously been made. Furthermore, the current system cannot appropriately capture the impact of sublethal effects either in the laboratory (lower tiers) or in the field (higher tiers) due to the limitations of the current tests (Tosi and Nieh, 2019). Nonetheless, a solution specific for highly social honey bees should be found: standard SPGs and risk assessment guidelines are not designed for superorganisms with a complex behavioural repertoire fundamental for honey bee colony functioning and fitness (Berenbaum and Liao, 2019). This has become a major challenge, as the criteria for PPP approval as listed in Regulation (EC) No 1107/20093 specifically requires the impact of PPPs on colony survival and development to be considered, taking into account larvae and behaviour of honey bees. Because chemicals such as PPPs can jeopardise both individual and colony health via sublethal alterations, we propose to specifically protect behavioural and physiological traits via novel definition of SPGs. A specific assessment of the variety of sublethal alterations caused by chemicals such as PPPs, together with an assessment of the best methods to implement in risk assessment, are urgently needed. Procedures described by the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD, 2005, 2009) for the development of novel methodologies could be implemented in risk assessments, allowing the assessment of sublethal effects that are relevant to bee health and applicable in risk assessment schemes. Possible candidates are tests in which the design and outcome are close to real world conditions, thus requiring little extrapolation. E.g. tests assessing bee locomotion ability using freely moving individuals to measure endpoints that can be relatively easy to connect to the real world in a quantitative manner (i.e. variation in distance travelled) would be preferred. Risk assessment should obtain high‐quality sublethal effect data that can feed both the classic risk assessment scheme and the novel (i.e. modelling) system‐based approach.

Multiple routes of exposures to chemicals

Honey bees are exposed to chemicals such as PPPs through multiple routes (EFSA PPR Panel, 2012). A honey bee colony is comprised of tens of thousands of bees who live inside their nest but also fly freely outside, with the potential for contact with chemicals both in their nest and in the field.

Honey bees can be exposed to chemicals through ingestion, contact and inhalation. The exposure can occur at a single point in time (acute) or over prolonged periods (chronic).

Bee exposure is influenced by multiple aspects:

Application methods: PPPs can reach the bees via multiple application methods, including e.g. spray, seed dressing, granules, fumigation and soil drenching.

Contaminated material: PPPs can contaminate the air (i.e. through spray treatments), the food (i.e. nectar, honeydew, pollen, water) and other materials (i.e. resin, water collected for thermoregulation purposes and in rare occasions guttation water) to which bees are exposed in the environment, as well as within their nest (i.e. wax, propolis, honey, beebread). Further information is provided in Section 3.2.2.2 .

Bee type: Exposure depends on the level of development (i.e. larvae, adults), the sex and caste (workers, queen, drones), the task performed (i.e. nurses, wax‐producing bees, foragers) and the season (i.e. summer vs. winter bees), as each one of these aspects underlies different nutritional and behavioural habits.

The genetic diversity of honey bees

Honey bees (Apis mellifera), both in managed and feral colonies, are represented by a complex of about 26 subspecies, of which 11 are present in EU, including the strain Buckfast that is distributed all over EU (Ruttner, 1988; Sheppard and Meixner, 2003; Appendix C ). In addition, there are some local populations that are well adapted to the local flora and area (Büchler et al., 2014; Hatjina et al., 2014). These locally adapted populations are referred to as ‘ecotypes’ (Strange et al., 2007; Meixner et al., 2013). E.g. the honey bee population from the Landes region, in France, has its annual brood cycle perfectly matched with the locally abundant floral source (Strange et al., 2007).

Apiculture in Europe is facing a rapid loss of biodiversity. Hybridisation due to increased movement of bees for honey production, pollination and overwintering in more favourable regions as well as trade of honey bee queens are currently the main threats to the diversity and conservation of the native and locally adapted populations (Meixner et al., 2010; Büchler et al., 2014; Momeni et al., 2021).

Under EU legislation, testing for approval of the use of an active substance is requested and conducted at the species level, without regard to the subspecies. The Western (A. m. mellifera), Italian (A. m. ligustica) and Carnolian (A. m. carnica) subspecies or the Buckfast strain are the most often studied, but rarely confirmed by DNA testing. These species cover mostly the Western and central zones of EU, under‐representing the southern part (e.g. Spain, Malta, Portugal, Sardinia, Greece, Cyprus). Before a PPP is authorised, its use needs to be tested and approved across three EU regulatory zones, where each zone corresponds to the natural range of distribution of some honey bee subspecies and ecotypes (Appendix C ). The South Zone is comprised of nine EU MS and is the most diverse (10 subspecies), whereas the North and Centre Zones, comprising six and 13 EU MS, respectively, have only one and two subspecies, respectively.

From a regulatory perspective, it is relevant to determine whether genetics (in terms of variations in behavioural and physiological responses to environmental changes as well as in terms of adaptation to local conditions and stressors) can influence the outcome of the risk assessment, e.g. are some subspecies more sensitive to pesticides than others and are some subspecies more resistant to other stressors, which could interact with pesticides, than others?

Knowledge on the influence of genetics on the sensitivity of honey bee subspecies to pesticides remains scarce. Too few studies have been conducted to allow robust conclusions to be drawn. Rinkevich et al. (2015) demonstrated different sensitivities to exposure to multiple chemicals in three honey bee subspecies, with toxicity to a mixture of acaricide and insecticides increasing sevenfold in A. m. primorski (a synthetic subspecies) and by five‐fold in A. m. ligustica, each compared with A. m. carnica. Further studies conducted on A. m. mellifera, A. m. ligustica and A. m. carnica found differences in sensitivity to neonicotinoids between colonies rather than between subspecies, highlighting the importance of the colony genetic pool (Laurino et al., 2013). Although such studies tend to demonstrate genetics as a significant factor to consider when assessing the toxicity of pesticides in honey bees, substantive evidence is currently missing.

In contrast, studies assessing resistance of honey bees to other stressors such as Varroa are more abundant. Survival to infestation by the mite was reported most notably in the African race A. m. scutellata in Brazil (Moretto et al., 1991; Rosenkranz, 1999; Locke, 2016), and in small subpopulations of European races as in Sweden (Gotland island) (Fries et al., 2003; Fries and Bommarco, 2007) and Russia (Danka et al., 1995; Rinderer et al., 2001, 2010) and others (review in Locke, 2016). However, to date, no specific bee subspecies in Europe has been shown to have more resistance to Varroa than others.

Finally, given the (hyper)polyandrous mating system of honey bees (a queen is inseminated by several males, supposedly on average 12, but most probably by dozens of males (Baudry et al., 1998; Withrow and Tarpy, 2018)), the genetic diversity of honey bees is translated into significant variability between and within colonies. Such diversity has an impact on risk assessments, as a considerable number of colonies would need to be tested in field conditions to detect expected field‐realistic effects such as sublethal effects (Cresswell, 2011).

2.2.2.2. The complexity of the environment of a honey bee colony

Bees operate in landscapes that are comprised of a range of stressors/factors, drivers and structures that determine the context for the expression of the exposure to PPPs. As noted in Section 2.2.2.1 , the colony is a complex adaptive system that is highly responsive to changes in this context. Therefore, the dynamism of the superorganism honey bee plays a central role in predictive models for multiple stressors and bees, influencing the time‐ and space‐specific conditions of individual bees, finally altering individual and societal decisions, resulting in emergent colony dynamics.

Context features of particular importance to the bee complex adaptive system include each of the following:

Landscape structure interacts with stressor exposure, resource availability, land use and bee decisions and dynamics through variation in landscape element structure. The composition of the landscape in terms of heterogeneity and structural pattern will interact with bee behaviour and ultimately result in colony variation. Landscape structure is therefore a complex confounding variable influencing the effect of land use and management.

Land use and management alters the landscape in complex ways. In many EU locations, agricultural land use predominates as a series of fields of differing sizes, usage and management, resource availability and patterns of PPP application (European Union, 2018). In complex landscapes, there will be co‐occurrence of PPPs, at a single point in time and/or sequentially, leading to co‐exposure of honey bee colonies to multiple chemicals throughout a single foraging season (Mullin et al., 2010; Tosi et al., 2018), including in honey stores and comb wax (Mitchell et al., 2017). Bee colonies living in complex landscapes are also co‐exposed to multiple stressors which prevalence and level varies dynamically, such as biological agents and nutritional stress.

Resource availability for bees varies depending on the landscape surrounding the colony. This variation depends on plant species and leads to spatial and temporal differences for each colony. Each plant has a peculiar blooming period with specific production of pollen and/or nectar in terms of quantity and quality (Couvillon et al., 2014; Donkersley et al., 2014; Baude et al., 2016). Thus, given the variability of both climate, weather and land use in EU, resource availability can vary greatly at smaller and broader geographic scales. Resource availability can also influence competition among bees, in particular between honey bees and bumble bees (Herbertsson et al., 2016). As a result of competition between honey bees and other plant‐pollinators, high‐density beekeeping in natural areas appears to have more serious negative, long‐term impacts on native pollinator biodiversity than was previously assumed (Valido et al., 2019).

Nutritional stress occurs in dearth of food that lead to suboptimal levels of food quality and quantity (i.e. decrease or lack of nutritional intake, also including its nutrients diversity), which can lead to an adverse impact on bee health (Naug, 2009).

Individual decisions made by honey bee foragers, including forager preference for particular fields, crops and non‐crops, are a key feature of bee colonies.

Climate and weather are crucial parameters driving bee health as they deeply influence their environment, e.g. leading to a seasonal sublethal and lethal impact of stressors (Tong et al., 2019) that can even impair winter colony survival.

-

Biological agents:

-

–

Infectious agents. Nosemosis is a disease in adult bees that affects the digestive tract and can cause acute diarrhoea, and in some cases mortality, in affected colonies (Fries, 1993). Nosema fungi are members of the microsporidia flora, a group of eukaryotic, obligate intracellular, single‐cell parasites. Two species of Nosema are found in honey bees: Nosema apis and N. ceranae (Fries, 1993; Higes et al., 2006).

-

–

Macroparasites. The mite Varroa destructor is a parasite of adult honey bees and their brood and the course of this parasitism is usually lethal (OIE, 2008). However, the role of V. destructor alone is not clear, because the mite is often a carrier and amplifier of viruses, in particular the DWV (Lanzi et al., 2006).

-

–

Bacteria. Paenibacillus larvae and Melissococcus plutonius are the agents responsible for American Foulbrood and European Foulbrood, respectively (Forsgren, 2010; Genersch, 2010).

-

–

Viruses. ABPV has been detected in several MS (Ribière et al., 2008; de Miranda et al., 2010). When fed, sprayed on or injected into, healthy bees, it makes them tremble and paralysed within a few days (Bailey, 1967). The virus can infect larvae, pupae and adult bees (de Miranda et al., 2010). ABPV commonly occurs at low levels in apparently healthy bee colonies and causes no reliable field symptoms (Aubert et al., 2008). However, several studies have reported that ABPV can be a major cause in several MS of mortality in colonies infected with V. destructor (Ribière et al., 2008; de Miranda et al., 2010). DWV is can be transmitted with V. destructor (Ribière et al., 2008). It is one of the most implicated predictors of honey bee health decline from various studies conducted in several MS (Budge et al., 2015). Individual infections with DWV may cause deformation of emerging bees and earlier death in adults, reducing the survival of winter honey bees (Dainat et al., 2012).

-

–

Predators. Vespa velutina (yellow‐legged hornet) is an Asian hornet species introduced in EU, reported for the first time in 2004 in France (Haxaire et al., 2006). It is an insect predator, in particular of honey bee colonies, and attacks foragers departing and returning to the hive (Arca et al., 2014; Monceau et al., 2014).

-

–

Beekeeping practices that deviate from best practices (Bee Research Institute, 2009; EFSA AHAW Panel, 2016) can substantially influence honey bee colony health.

Other stressors of anthropogenic origin, e.g. pollutants, roads and manicured parklands (etc.), may also be relevant (Winfree et al., 2009; Søvik et al., 2015; Bellucci et al., 2019).

3. A systems‐based approach of multiple stressors in honey bee colonies

3.1. A proposed systems‐based approach