Introduction

Information capturing the U.S. Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) workforce is at best nebulous in federal data repositories. Having an understanding of CNS human capital may provide direction for stakeholders to expand CNS workforce capacity and challenge policies which historically prevented CNSs from being recognized as Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs). This study expands on previous work presented on CNSs registered in the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) with a National Provider Identifier (NPI).1 The objective of this study was to describe the U.S. CNS workforce based on self-reported publicly available information from the NPPES NPI Registry.2

Background

Depending on state-specific rules and regulations, many CNSs have the authority to order tests, diagnose, prescribe treatments, and manage patients as an independent licensed provider. In addition to direct patient care, the CNS impacts nurses and nursing, organizations and systems, making the CNS the most versatile advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) working in the acute, post-acute, and ambulatory settings.3,4 In 1997, Congress recognized the unique role of the CNS when it passed the Balanced Budget Act. This act allowed CNSs to directly bill for their services through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) under Part B participation in Medicare. With the Affordable Care Act signed into law in 2010, the role of the CNS became pivotal to meet the challenges for transforming healthcare systems by providing care that is safe, high quality, affordable and accessible.

The NACNS position paper Impact of the Clinical Nurse Specialist Role on Costs and Quality of Healthcare describes research where CNSs improved prenatal care, provided preventive and wellness screenings for employers, psychiatric/behavioral care to reduce depression, reduced costs of chronic care, prevented hospital-acquired conditions, reduced the length of stay in acute and community based settings, and prevented readmissions.5 A critical review of the literature also reported improved patient satisfaction, shorter hospital length of stay and lower costs when patients with chronic illness were managed by a CNS.6 Nonetheless, more than a decade after the landmark national paper, Consensus Model for APRN Regulation: Legislation, Accreditation, Certification and Education,7 articulated the unique criteria and scope of practice of each APRN, the CNS role continues to face challenges of role ambiguity and visibility.

The Administrative Simplification provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, mandated the adoption of standard, unique NPIs for healthcare providers.8 The purpose of these provisions were to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the electronic transmission of health information. CMS developed the NPPES to assign NPIs to healthcare providers. The NPI is a unique, unduplicated, 10-digit identification number used to identify healthcare providers who practice in HIPAA covered entities.

All healthcare providers that bill Medicare for services, are required to obtain an NPI and use this identifier in all HIPAA related transactions (i.e. electronic exchange of information between two parties to carry out financial or administrative activities related to healthcare)9. However, often, the healthcare organization’s NPI is used when CNSs work within those entities. Provider information in the NPPES is self-reported, and some of the data generated include: the provider’s NPI number, name, location of practice, self-proprietorship, sex, and clinical specialty. Each provider (regardless of profession) can enter up to 15 different clinical specialties using specific taxonomy codes. Much of the information supplied in NPPES, is available in a searchable public database.2 Although the CNS has a long and substantial history as an APRN, little is known about the number, specialties, and geographic distribution of CNSs registered with an NPI. Therefore, the research question posed was: What are the different clinical practices, population foci/specialty, and geographic locations of the CNSs in the United States?

Methods and Analysis

A descriptive exploratory approach was employed to identify CNSs in the NPI registry. The publicly available file from the NPPES website containing accumulative NPI data through December 201910 was downloaded. The data were imported into Stata11 for cleaning and preparation followed by import into R12 for analyses. The significance level α=0.05 was used in all analyses. Healthcare entities/organizations were removed and extracted self-reported CNSs from the dataset by isolating CNS designated taxonomy codes.13

The total sample was summarized using tabulated frequencies for a variety of characteristics: sex, if sole proprietor, region of U.S., urban/rural status, nurse practitioner (NP) status, and state/location. To determine rurality of CNS practice, NPI zip codes were matched with the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) eligible zip code dataset.14 Nurse Practitioner (NP) taxonomy codes were matched to CNS taxonomy codes to identify those individuals who were both CNS and NP. The count and percent of nurses in each CNS and NP specialty were reported for the total sample and stratified by urban/rural status. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess whether the proportions differed by urban/rural status. Maps of the U.S. were created to display the spatial location of all CNSs using the usmap R package.15

Among the subset of CNSs who identified as an NP, Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the association between various CNS and NP specialties (i.e. whether nurses who identified with a particular CNS specialty were also likely to identify with a particular NP speciality). When reporting p-values in tables, both the original p-values and multiple-testing adjusted p-values were included, which can be used to control a false-discovery-rate (FDR)16. The FDR p-values penalize the original p-values by accounting for the total number of statistical tests performed. Thus, the FDR p-values tend to be larger and reduce the chance of a false positive result.

To detect any potential trends in CNS population foci and clinical specialties, new CNS NPI enumerations were examined between 2015–2019. Run charts were used to visually assess changes in new NPI enumerations over time (i.e. line graphs of new NPI enumerations plotted over calendar quarters). Run charts can be used to assess trends (e.g. new NPI enumerations increasing or decreasing over time) and use rules to determine whether there is evidence of non-random change over time.17,18

Results

The NPI dataset contained 6,195,389 healthcare providers and healthcare entities/organizations; of these, 10,000 self-reported as CNSs (Table 1). The majority of CNSs were female (92.0%), and 2,642 (26.4%) were sole proprietors. Geographically, a minority practice rurally. Most practice in the Midwest (29.8%) or the South (31.7%). Nearly 20% of CNSs identifying themselves as an NP. The geographic region of practice by state is displayed in Figure 1 and in supplement Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of 10,000 Clinical Nurse Specialists

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 9199 (92.0) |

| Sole Proprietor | 2642 (26.4) |

| Also Practices as Nurse Practitioner | 2230 (22.3) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 1981 (19.8) |

| Midwest | 2978 (29.8) |

| South | 3171 (31.7) |

| West | 1846 (18.5) |

| Other | 24 (0.2) |

| Rural | 1016 (10.2) |

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Clinical Nurse Specialists by zip code

Map of 9897 CNSs due to 17 CNSs in Puerto Rico and Ontario, and 86 within armed forces’ zip codes that we were unable to retrieve the necessary latitude and longitude coordinates.

There are 34 specific clinical specialty taxonomy codes for CNSs to utilize when registering for an NPI number (Table 2).13 The majority of CNSs (94.7%) reported one clinical specialty. Surprisingly, 530 CNSs reported working in up to 8 different specialties (Table 3.). Many (1576, 16.6%) of the CNSs that did not choose a population foci/specialty (i.e. identifying themselves as a Clinical Nurse Specialist absent of a clinical specialty). These CNSs without a specialty were relabeled in the tables as “not otherwise specified” [CNS-NOS]). The specialties most frequently identified were: Adult Health (1447, 15.2%), Mental Health Adult (1289, 13.6%), and Psychiatric/Mental Health (1128, 11.9%), exceeded 1,000, indicating Mental Health CNSs as a major area of practice among CNSs.

Table 2.

Clinical Nurse Specialist reporting one specialty/foci by taxonomy code

| Description | Clinical Nurse Specialist Taxonomy Code | n=9470 |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | 364S00000X | 1576 |

| Acute Care | 364SA2100X | 443 |

| Adult Health | 364SA2200X | 1447 |

| Chronic Care | 364SC2300X | 14 |

| Community Health/Public Health | 364SC1501X | 147 |

| Critical Care Medicine | 364SC0200X | 170 |

| Emergency | 364SE0003X | 90 |

| Ethics | 364SE1400X | 19 |

| Family Health | 364SF0001X | 803 |

| Gerontology | 364SG0600X | 361 |

| Holistic | 364SH1100X | 0 |

| Home Health | 364SH0200X | 57 |

| Informatics | 364SI0800X | 5 |

| Long-term Care | 364SL0600X | 29 |

| Medical-Surgical | 364SM0705X | 315 |

| Neonatal | 364SN0000X | 113 |

| Neuroscience | 364SN0800X | 51 |

| Occupational Health | 364SX0106X | 26 |

| Oncology | 364SX0200X | 229 |

| Oncology, Pediatrics | 364SX0204X | 9 |

| Pediatrics | 364SP0200X | 393 |

| Perinatal | 364SP1700X | 34 |

| Perioperative | 364SP2800X | 66 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health | 364SP0808X | 1128 |

| Mental Health, Adult | 364SP0809X | 1289 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health, Child & Adolescent | 364SP0807X | 253 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health, Child & Family | 364SP0810X | 64 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health, Chronically Ill | 364SP0811X | 5 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health, Community | 364SP0812X | 24 |

| Psychiatric/Mental Health, Geropsychiatric | 364SP0813X | 27 |

| Rehabilitation | 364SR0400X | 27 |

| School | 364SS0200X | 9 |

| Transplantation | 364ST0500X | 4 |

| Women’s Health | 364SW0102X | 243 |

Table 3.

Number of Clinical Nurse Specialist specialties by region

| Specialties | Northeast | Midwest | South | West | Other* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1881 | 2818 | 3008 | 1740 | 23 | 9470 |

| 2 | 84 | 133 | 131 | 89 | 1 | 438 |

| 3 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 8 | 0 | 62 |

| 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 15 |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 1981 | 2978 | 3171 | 1846 | 24 | 10000 |

Other: Armed Forces, Guam, Ontario, Canada, and Puerto Rico

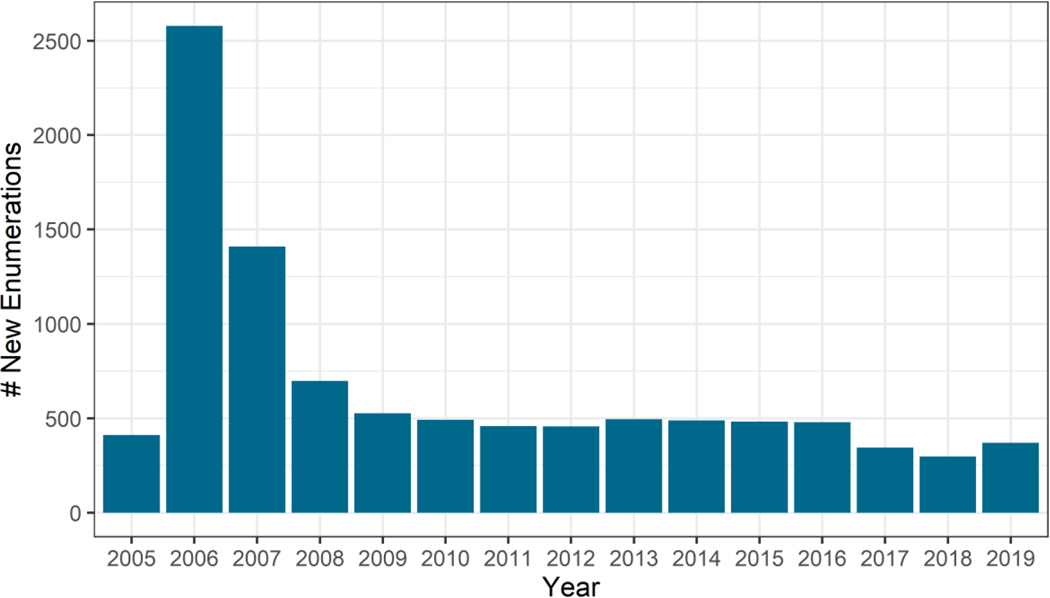

Historical data related to new NPI enumerations (initial registrations) when NPIs became required for billing purposes were examined. New NPI enumerations began in 2005 but peaked in 2006 with >2500 registrants. This figure gradually tapered off to approximately 500 and plateaued in 2009 to present (Figure 2). These data, point to a slowing of CNSs obtaining a new NPI. Despite the benefit of having an NPI, surprisingly, 3,122 (31.2%) of CNSs have not updated their NPI information since their initial registration.

Figure 2.

New national provider identifier enumerations by year

CNS practice in urban/rural locations

Among the 9,470 nurses who identify with only a single CNS specialty (Table 4), the majority worked in Psychiatry (29.5%), Adult Geriatrics (22.4%), CNS-NOS (16.6%), Family Health (8.5%), and Acute Care (8.1%). The majority of CNSs work in urban (90.0%) vs rural (10.0%) areas. The distribution of CNSs by urban and rural locations significantly differed for Family Health, CNS-NOS, Acute Care, Adult Geriatrics, Community Public Health, Oncology, and Post Acute (FDR p-value <0.05). However, most of these differences were relatively small, for example, only two specialties differed by more than 4%: Family Health (Urban 7.7%, Rural 15.5%) and CNS-NOS (Urban 17.1% vs. Rural 12.6%). To visualize the concentration and geographic location of CNSs practicing in the rural settings, rural Zip Codes were plotted by location (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Clinical Nurse Specialists with only one specialty by urban/rural status [count(%)]

| Speciality1 | Total N=9470 | Urban N=8517 | Rural N=953 | p-value | FDR p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| family_health | 803(8.5) | 655(7.7) | 148(15.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| cns_nos3 | 1576(16.6) | 1456(17.1) | 120(12.6) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| acute_care4 | 769(8.1) | 723(8.5) | 46(4.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| adult_gero5 | 2123(22.4) | 1940(22.8) | 183(19.2) | 0.012 | 0.030 |

| community_public_health | 147(1.6) | 109(1.3) | 38(4.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| cns_psych6 | 2790(29.5) | 2490(29.2) | 300(31.5) | 0.155 | 0.220 |

| oncology7 | 238(2.5) | 226(2.7) | 12(1.3) | 0.006 | 0.018 |

| post_acute8 | 113(1.2) | 91(1.1) | 22(2.3) | 0.002 | 0.008 |

| pediatrics | 393(4.1) | 361(4.2) | 32(3.4) | 0.230 | 0.279 |

| womens_health9 | 277(2.9) | 242(2.8) | 35(3.7) | 0.155 | 0.220 |

| neonatal | 113(1.2) | 107(1.3) | 6(0.6) | 0.113 | 0.199 |

| neuro | 51(0.5) | 50(0.6) | 1(0.1) | 0.058 | 0.124 |

| holistic | 19(0.2) | 15(0.2) | 4(0.4) | 0.117 | 0.199 |

| school | 9(0.1) | 7(0.1) | 2(0.2) | 0.227 | 0.279 |

| chronic_care | 14(0.1) | 12(0.1) | 2(0.2) | 0.645 | 0.731 |

| informatics | 5(0.1) | 5(0.1) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| transplant | 4(0.0) | 4(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

Specialties are sorted from largest to smallest absolute difference in proportions |Urban – Rural|

False discovery rate (FDR) multiple testing adjusted p-value

CNSs not choosing a population foci/specialty labeled as “not otherwise specified” [cns-nos]

Includes- acute care, perioperative, critical care medicine, and emergency

Includes- adult health, medical-surgical, and gerontology

Includes – all psych/mental health specialties

Includes- oncology and oncology, pediatrics

Includes- home health, long-term care, and rehabilitation

Includes- women’s health and perinatal

Figure 3.

Location of Clinical Nurse Specialists practicing within rural zip codes (n=1016)

Table 5 reports on the 1,932 CNSs who identify with a single NP specialty by urban/rural status. Acute-care specialty was the only NP specialty that significantly differed between urban and rural locations (6.8 vs. 2.3%, p-value = 0.007), however, the multiple testing adjusted p-value was not significant (FDR p-value = 0.131).

Table 5.

Clinical Nurse Specialists also practicing as Nurse Practitioners urban versus rural status [count(%)]

| Speciality1 | Nurse Practitioner Taxonomy Code | Total N=1932 | Urban N=1712 | Rural N=220 | p-value | FDR p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| np_psych | 363LP0808X | 451(23.3) | 388(22.7) | 63(28.6) | 0.052 | 0.294 |

| np_acutecare | 363LA2100X | 122(6.3) | 117(6.8) | 5(2.3) | 0.007 | 0.131 |

| np_family | 363LF0000X | 435(22.5) | 377(22.0) | 58(26.4) | 0.146 | 0.405 |

| np-nos3 | 363L00000X | 401(20.8) | 347(20.3) | 54(24.5) | 0.157 | 0.405 |

| np_adulthealth | 363LA2200X | 257(13.3) | 236(13.8) | 21(9.5) | 0.091 | 0.328 |

| np_pediatrics | 363LP0200X | 94(4.9) | 89(5.2) | 5(2.3) | 0.065 | 0.294 |

| np_gero | 363LG0600X | 58(3.0) | 56(3.3) | 2(0.9) | 0.057 | 0.294 |

| np_womenshealth | 363LW0102X | 38(2.0) | 31(1.8) | 7(3.2) | 0.191 | 0.429 |

| np_neonatalcc | 363LN0005X | 16(0.8) | 16(0.9) | 0(0.0) | 0.243 | 0.437 |

| np_pediatricscc | 363LP0222X | 2(0.1) | 1(0.1) | 1(0.5) | 0.215 | 0.430 |

| np_primarycare | 363LP2300X | 24(1.2) | 22(1.3) | 2(0.9) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_criticalcare | 363LC0200X | 5(0.3) | 5(0.3) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_communityhealth | 363LC1500X | 4(0.2) | 4(0.2) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_obgyn | 363LX0001X | 12(0.6) | 11(0.6) | 1(0.5) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_occupational | 363LX0106X | 2(0.1) | 2(0.1) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_neonatal | 363LN0000X | 10(0.5) | 9(0.5) | 1(0.5) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_perinatal | 363LP1700X | 1(0.1) | 1(0.1) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| np_school | 363LS0200X | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

Specialties are sorted from largest to smallest absolute difference in proportions |Urban – Rural|

False discovery rate (FDR) multiple testing adjusted p-value

NPs not choosing a population foci/specialty labeled as “not otherwise specified” [np-nos]

Association between NP and CNS specialties

Spearman’s correlation (“”) was used to assess the association between various CNS and NP specialties to determine whether CNSs who identified with a particular CNS specialty, were also likely to identify with a particular NP specialty. Table 6 identifies the highest correlations from 0.36 to 0.70 (p-values <0.001). Thus CNSs who identified working in pediatrics, were likely to identify as NP pediatrics (=0.70); neonatal (=0.61); Women’s Health (=0.58), Acute Care (=0.48); and Family Health (=0.36). Supplemental Table 2 provides a comprehensive list of all correlations between CNS and NP specialties, along with multiple-testing adjusted p-values. Note: the majority of correlations were relatively small (e.g. <0.1) suggesting little connection between the CNS and NP’s population foci/specialties.

Table 6.

Highest Clinical Nurse Specialist and Nurse Practitioner correlations

| Clinical Nurse Specialist | Nurse Practitioner | Spearman’s |

|---|---|---|

| pediatrics | pediatrics | 0.70 |

| neonatal | neonatal | 0.61 |

| womens_health1 | womenshealth | 0.58 |

| acute_care2 | acutecare | 0.48 |

| family_health | family | 0.36 |

Includes- women’s health and perinatal

Includes- acute care, perioperative, critical care medicine, and emergency

CNS population foci and clinical specialty run charts

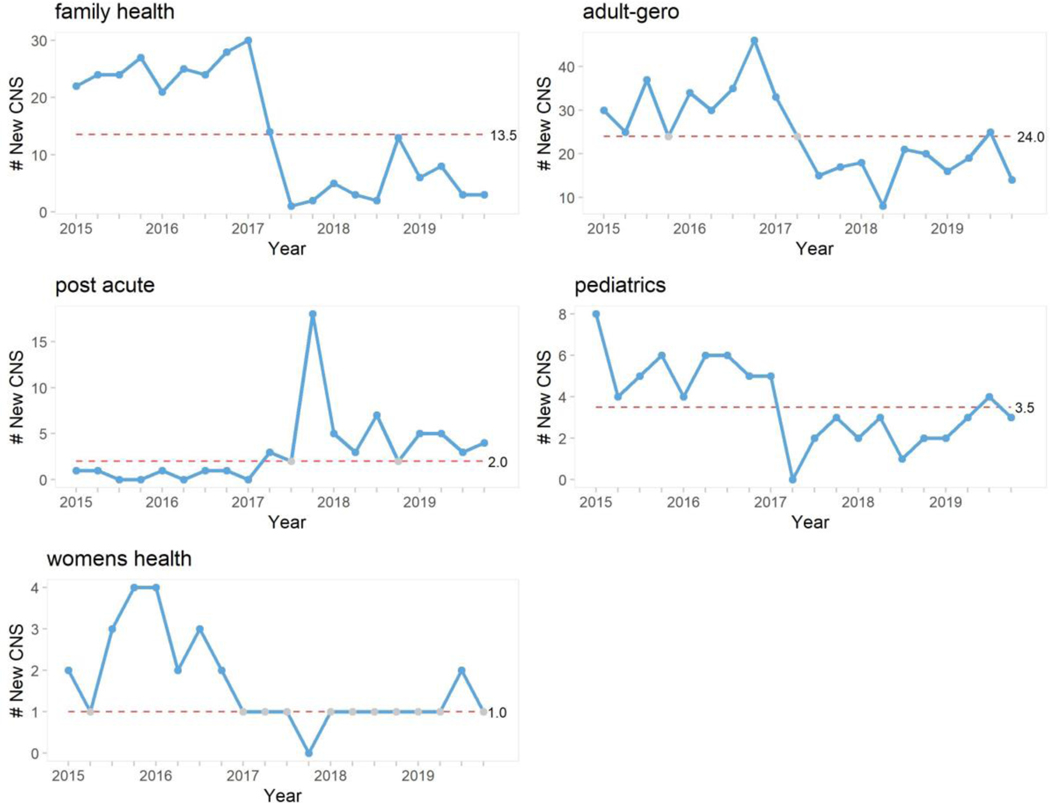

Run charts were used to evaluate the quarterly trends of CNSs (frequency ≥100) by population foci/specialty from 2015–2019. Run charts plot a series of measures (new CNSs) over time, with the median as a horizontal line. Using the rules of Anhøj,18 five CNS specialties had evidence of non-random change in new NPI enumerations (Figure 4.): Family Health, Adult-Gero, Pediatrics and Women’s Health had decreasing trends over time, while Post Acute had an increasing trend. In addition, when evaluating the trend lines for the past 3-years, there were positive upward trends (all points above the median) in CNS-NOS, CNS-Psych (Supplemental Figure 1.), and Post Acute; however, only Post Acute had evidence for non-random change.

Figure 4.

Run charts of quarterly trends of new national provider identifier enumerations by clinical specialty/foci

These run charts identified five changes in new NPI enumerations from 2015 with family health, adult gero, pediatrics and women’s health showing a decline and post acute showing a trend toward increasing enumerations. The horizontal dashed middle line gives the median number of new enumerations. Run charts were made using the qicharts2 R package (Anhøj O. Qicharts2: Quality Improvement Chart, 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/qicharts2/vignettes/qicharts2.html). Adult-gero includes adult health, medical-surgical, and gerontology; post acute includes home health, long-term care, and rehabilitation; and women’s health includes women’s health and perinatal.

Discussion

Findings from this study differ from previously presented data1 because of the taxonomy codes used, instead of free-text credentials. When registering for an NPI, the provider has an opportunity to free-text their credentials such as CNSs identifying themselves as an advanced practice nurse (APN) or APRN while using the taxonomy code “364S00000X” (Clinical Nurse Specialist). Use of “APN or “APRN” in the free-text credentialing field tends to be nebulous and leaves the reader with a question on type of APN or APRN the provider is self-reporting. Utilizing the NPI data by taxonomy code for interpretation, clarified and classified the CNS population foci/specialty.

The establishment in recent years of an NPI, offers a different method for counting and categorizing the healthcare workforce involved in clinical care.19 In particular, the NPI registry was utilized to identify CNSs in clinical practice who are most likely billing for their services. However, in a recent National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS) webinar of 110 CNSs, only 3.6% reported billing for their services.20 Rationale for CNSs’ not registering for an NPI unknown. Potentially, if CNSs understood the importance of being counted in the healthcare workforce (e.g. changes in local and national regulation/legislation), there would be greater participation. Since there is no charge for enrolling in the NPI, cost should not be a factor in the CNS’s decision. Additionally, some issues surrounding the accuracy of the NPI are, once a CNS has an NPI, there are no scheduled requests for updated information. Despite instructing providers to update their information in NPPES within 30 days of a change, the data suggest this may not be happening. The date a change is made within the NPI profile is identified, however there is no record on the frequency of changes performed. Obsolete information in the NPPES does not de-activate or suspend a provider’s NPI, and there is no explicit penalty for a provider having outdated information within NPPES.

The majority of CNSs work in the urban environment, which is not surprising since more opportunities for CNS occur in urban areas especially in acute care centers. On the other hand, it was interesting to see the percentage of CNSs specializing in psychiatry were similar among urban and rural areas (~30% each). Overall, large differences in the percentages of CNS specialties between urban and rural areas were not found. For example, only two specialties differed by more than 4% (urban, rural): Family Health (7.7%, 15.5%) and CNS-NOS (17.1%, 12.6%). When assessing whether CNSs who identified with a particular CNS specialty was also likely to identify with a particular NP specialty, the strongest associations in pediatrics, neonatal, women’s health, acute care, and family health (Table 6.)

Analysis of quarterly patterns of NPI enrollment (2015–2019), demonstrated a trend toward decrease in family health, adult-gero, pediatrics, and women’s health; with a slight increasing trend for post acute. However, most specialties had small numbers, suggesting further monitoring of trends is necessary as CNSs register for an NPI expands. Although run charts did not find significant change in new psychiatric/mental health NPI enumerations, there was a run of 4-consecutive points above the median line in the last 4-quarters of 2019, suggesting an upward trend. This is interesting because the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) retired the psychiatric-mental health clinical nurse specialist (PMHCNS) board certification in 2014. Potentially, CNSs are moving from a previous area of healthcare into psychiatric mental health or becoming boarded in a population foci (e.g. adult-gero) and working in psychiatric/mental health.

Implications

Research

Recently, NACNS advocated for all practicing CNSs to obtain an NPI so that each CNS can be counted to demonstrate the CNS workforce’s strength in numbers.21 However, the CNS role continues to be strikingly absent in workforce titles and federal databases. A recent 2018 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Nursing Workforce analysis estimates there are 89,122 CNSs.22 The same report estimates 47,078 are actively certified as a CNS with 10,395 new graduates from 2014 to 2018. This analysis indicate only 10,000 CNSs are registered with an NPI. So where are the other 79,122 CNSs, and what population foci/specialty are they working in?

Research is necessary to better understand the roles and practices of the U.S. CNS workforce and identify potential locality and specialty based CNS shortages and surpluses. Linking the NPI registry with other federal databases such as the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) could reveal the workforce gaps CNSs can fill while clarifying U.S. health workforce projections. Research identifying the direct CNS to population ratio is necessary to strengthen the CNS workforce especially in rural, frontier, and underserved localities where the CNS can impact patient/populations, nurses/nursing, and systems/organizations.

Policy and Practice

Imagine for a moment if every CNS obtained an NPI. The ability to impact policy impeding against CNS title recognition would be easier to change. From a federal perspective, an example might be the U.S. government system of classifying occupations, the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) System. The SOC system, classifies nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists as separate APRNs.23 The CNS is the only APRN classified within the category of registered nurses. Embedding CNS workforce data within the SOC registered nurse category hides CNSs contributions and further confusion and misunderstanding about the CNS role as an APRN.24 Having over 70,000 CNSs in a federal database (e.g. NPI Registry) could move the SOC policy to exclude CNSs from the registered nurse category, and thereby providing a new precedent for CNS title recognition. From a state-level perspective, using a federal database as leverage to demonstrate CNS workforce numbers may contribute to changing resistant state rules and regulations in recognizing the CNS as an APRN and confer equivalent privileges and title protection.

Another example of policy change surrounding CNS practice and title recognition resides in the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). CNSs who prescribe with a DEA number, must indicate they are a mid-level practitioner. However, when applying for a DEA number, the only choice for APRNs is NP.25 That said, recent APRN Consensus Model data indicate CNSs can prescribe in 23 states.26 This disconnect between practice reality and policy needs to be addressed and reconciled. Rationale for the DEA to alter policy and include CNS taxonomy within the application and registration process for a DEA number could be supported by overwhelming evidence of a large CNS workforce with an NPI.

CNS Education

All CNSs and CNS students should obtain an NPI regardless of billing status.21 Requiring CNS students to register for an NPI helps prepare them for professional practice and should receive the same emphasis as licensure and certification. Having a federal database with up to date records on current CNSs practicing in the U.S. by location and population foci/specialty can inform universities and their community partners with needs assessment data in developing new or enhanced CNS education programs. Understanding current CNS localities coupled with population foci/specialty practice could be indicative for government funding and private philanthropic activities for student scholarships aimed to expand the CNS workforce.

NPPES NPI Registry Database

This project reveals opportunities for NPPES to refresh its database into a more robust healthcare provider workforce repository. Recommendations to enhance this database include 1) requirement to update NPI provider data every 2–5 years to enhance accuracy; 2) review and update the APRN taxonomy codes to better reflect contemporary clinical practice; 3) metrics that inform workforce to population ratios, access to care shortages, and employment at a critical shortage facility; and 4) indicator of highest academic achievement (e.g. DNP or MS). These changes in the NPI registry would help further research, policy, practice and education efforts for the APRN community.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study is a snapshot of limited data points the NPPES provides in describing the type of work CNSs perform. Second, as indicated earlier, approximately 11.2% of the estimated CNSs working in the U.S. were captured in this study, and therefore the findings cannot be generalized throughout the entire CNS profession. The fact that 31.2% of CNSs with an NPI, have not updated their record since their initial enumeration, leads to questions about the accuracy in numbers of CNSs currently in practice. This is especially true because there is no penalty or automation to remove providers in the NPI registry, even if no billing or activity has occurred since the initial enumeration. Finally, the plotting of CNS practice locations may not be accurate with sole proprietors because it is unclear if their business address is the CNS’s home or actual practice location.

Conclusion

Of the estimated 89,122 CNSs in the U.S., only 11.2% of the CNS workforce is registered in the NPI registry. This study provides evidence that every CNS must register for an NPI to be counted in the total workforce denominator. Further research is necessary to understand the rationale for CNSs not registering for an NPI. The lack of an accurate, federal, comprehensive, CNS workforce database, may undermine the ability to monitor and enhance healthcare policies designed to improve access to care and to intervene when necessary to address barriers to care.19 The findings also suggest the need to continue monitoring new NPI enumerations within CNS population foci and clinical specialties to identify increasing or decreasing trends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging award number: 5T32AG044296-05.

Disclosures: Dr. Reed is the President of the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. Dr. Arbet and Mrs. Staubli declares no conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Sean M. Reed, University of Colorado, College of Nursing, ED 2 North 13120 E. 19th Ave Room 4317, Aurora, Colorado 80045, Phone: 303-724-0735.

Jaron Arbet, Colorado School of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics and Informatics, Fitzsimons Building, Room W4167, Aurora, Colorado 80045, Phone: 303-724-3827.

Linda Staubli, UCHealth – Denver Metro Region, 12605 E. 16th Ave, Aurora, Colorado 80045, Phone: 720-848-8656.

References

- 1.Reed SM, Staubli L, Thurby-Hay L. The clinical nurse specialist: Findings within the national provider identifier registry. Podium presented at the: National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists Annual Conference; 2019; Orlando. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Plan & Provider Enumeration System: National Provider Identifier Registry. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/

- 3.Reed SM. Response to “Description of work processes used by clinical nurse specialists to improve patient outcomes.” Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(2):137–138. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. Statement on Clinical Nurse Specialist Practice and Education (3rd Ed). NACNS; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Impact of the Clinical Nurse Specialist Role on Costs and Quality of Healthcare. National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists; 2013. Accessed July 31, 2020. https://nacns.org/advocacy-policy/position-statements/impact-of-the-clinical-nurse-specialist-role-on-the-costs-and-quality-of-health-care/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore J, McQuestion M. The clinical nurse specialist in chronic diseases. Clin Nurse Spec CNS. 2012;26(3):149–163. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3182503fa7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.APRN Joint Dialogue Group. Consensus Model for APRN Regulation: Licensure, Accreditation, Certification & Education. Published online July 7, 2008. https://www.ncsbn.org/Consensus_Model_for_APRN_Regulation_July_2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). National Plan and Provider Enumeration System: National Provider Identifier Registry. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Transactions Overview | CMS. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/Transactions/TransactionsOverview

- 10.NPI Files. Accessed December 13, 2019. http://download.cms.gov/nppes/NPI_Files.html

- 11.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. StataCorp LLC; 2019. https://www.stata.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. The R Foundation; 2018. https://www.r-project.org/sss [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Care Provider Taxonomy Code Set. Accessed December 13, 2019. http://www.wpc-edi.com/reference/codelists/healthcare/health-care-provider-taxonomy-code-set/

- 14.Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA). Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Data Files. Official web site of the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Lorenzo P Usmap: US Maps Including Alaska and Hawaii.; 2019. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/usmap/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):46–51. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anhøj J, Olesen AV. Run charts revisited: a simulation study of run chart rules for detection of non-random variation in health care processes. PloS One. 2014;9(11):e113825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bindman AB. Using the National Provider Identifier for health care workforce evaluation. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(3). doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.b03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed SM. Resurgence of the Clinical Nurse Specialist: Elevating the Visibility and Value of the CNS. Presented at the: National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists Webinar; September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed SM. National Provider Identifier: Why Every Clinical Nurse Specialist Needs One. Clin Nurse Spec CNS. 2020;34(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses Codebook. Nursing Workforce Survey Data. Published 2018. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/nursing-workforce-survey-data [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018. Standard Occupational Classification System. Accessed May 18, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/soc/2018/major_groups.htm#29-0000

- 24.Horner SD. Letter to the Standard Occupational Classification Policy Committee. Published online September 16, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2020. http://nacns.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/SOC-Comments160916.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.DEA Form 224. Accessed May 19, 2020. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugreg/reg_apps/224/224_instruct.htm#1

- 26.The National Council of State Boards of Nursing. NCSBN scoring grid: APRN consensus model by state updated April 2019. NCSBN. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://www.ncsbn.org/APRN_Consensus_Grid_Apr2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.