Abstract

Background

Examination of the format and framing of the graphic health warnings (GHWs) on tobacco products and their impact on tobacco cessation has received increasing attention. This review focused on systematically identifying and synthesizing evidence of longitudinal studies that evaluate different GHW formats and specifically considered GHW influence on perceived risk of tobacco use and quit intentions.

Methods

Ten databases were systematically searched for relevant records in December 2017 and again in September 2019. Thirty-five longitudinal studies were identified and analyzed in terms of the formatting of GHWs and the outcomes of perceived risk and quit intentions. Quality assessment of all studies was conducted.

Results

This review found graphics exceeding 50% of packs were the most common ratio for GHWs, and identified an ongoing reliance on negatively framed messages and limited source attribution. Perceived harms and quit intentions were increased by GHWs. However, wear-out effects were observed regardless of GHW format indicating the length of time warnings are present in market warrants ongoing research attention to identify wear out points. Quit intentions and perceived harm were also combined into a cognitive response measure, limiting the evaluation of the effects of each GHW format variables in those cases. In addition, alternative GHW package inserts were found to be a complimentary approach to traditional GHWs.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated the role of GHWs on increasing quit intentions and perceptions of health risks by evaluating quality-assessed longitudinal research designs. The findings of this study recommend testing alternate GHW formats that communicate quit benefits and objective methodologies to extend beyond self-report.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-021-10810-z.

Keywords: Tobacco, Graphic health warning, Systematic review

Background

Understanding cognitive reactions after exposure to graphic health warnings (GHWs), is crucial when considering the design and format of GHWs. This review focuses on perceived harm reactions that are operationalized in the literature as thinking about the risks of smoking [1], perceived likelihood of harm from smoking [2] and identifying that smoking causes tobacco related diseases [3], as well as quitting intentions, that are measured as the intention to quit smoking in a certain period of time (i.e. next week) [4] or the extent to which health warning labels make the person more likely to quit smoking [5].

The literature offers theoretical explanations of health risk communications that explain GHWs constructs (perceived risk, cessation intention, smoking behavior) and their relationships [6]. For instance, the extended parallel process model (EPPM) indicates that if a high level of severity from engaging in certain unhealthy behaviors was perceived, individuals will be motivated to behave in order to avoid such risks [7]. Similarly, if individuals hold the belief that they are capable of changing their behavior (perceived self-efficacy) as well as their risk of negative outcomes (perceived response efficacy), the healthier behavior will be motivated to happen. Thus, the EPPM suggests that GHWs messaging that aims to increase smokers’ motivation to quit should include convey messages that contain both threat and efficacy [6].

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) specifies the importance of labelling health warnings describing the harmful effects of tobacco use in Article 11 [8] but did not provide detailed instructions on the design and format of GHWs apart from generic descriptions of being “large, clear, visible and legible” (p. 10). Depending on the design and format of GHWs, they can have varying effects on cognitive reactions (including perceived risks and quit intentions). The main GHW variable evaluated is format, which includes text vs. graphic warning (or a combination of both), size of the warning on package (i.e. 50%), location (i.e. front of the package) and color. A recent study indicated that a combined disclosure format (text with low/high emotion images) increased risk perceptions and quit intentions relative to text-only [9]. Other evidence suggests that emotionally evocative images depicting hazards (i.e. GHWs proposed by the US FDA) are not effective in communicating wider smoking risks when compared to text featuring irrelevant pictures (e.g. depictions of a car accident), or text-only [10].

Other contradictions are evident for message framing. Positive versus negative framing of tobacco warning messages have been recently examined, contrasting the effects of GHWs communicating the harmful effects of smoking (negative framing) or the benefits of quitting (positive framing). Studies that investigated text message framing effects of tobacco health warnings have found greater efficacy when messages are framed in the negative [11, 12]. However, others identify support for the use of positive message framing when targeting illness prevention behaviors including smoking cessation [13] and yet others have identified reactance to negative messages (fear appeals) for smoker groups [14]. Examination of a wider evidence base for message framing indicates support for the effectiveness of positively framed messages to invoke behavioral change. Examination of 14 direct tests of positive versus negative appeals indicate that 11 studies offer evidence that positive appeals are stronger when compared to negative approaches [14–24]. Hence there remains some uncertainty regarding the role of alternate message framing formats that may further enhance the effectiveness of GHWs. A systematic and comprehensive review of message framing and GHW format is required.

Recent literature reviews have reported the effects of strengthened GHW formats (i.e. larger in size and message) on knowledge and attitudes, attention [25], active smoker’s behavior [26], and young adults including adolescents [27, 28]. Noar et al’s review has a similar focus on longitudinal studies and examines several of the outcomes of interest in the current study. Yet, there is no recent systematic review that has examined the impact of different formats of GHWs on communicating smoking health risks and quit intentions. Because of the paucity of evidence from independent sources, it is important to look at evidence from peer-reviewed journals reporting empirical data. Therefore, this review aims to systematically identify and synthesize evidence from longitudinal studies that have examined GHW formats and their effect on perceived risk of tobacco use and quit intentions of both smokers and non-smokers. The research question of this review is:

What warning and/or disclosure formats are optimal for communicating the risk of smoking on health and quit intentions?

Method

The PRISMA guidelines [29] were followed to conduct the systematic search in order to ensure completeness and transparency.

Key search terms

The following search terms were used for this review:

tobacco OR cigar* OR bidis OR beedi OR e-cigar* OR heat-not-burn OR shisha OR “heat not burn” OR “roll your own” OR roll-your-own

AND.

warning* OR pictorial OR graphic OR packag*

AND.

intervention* OR evaluation OR trial OR campaign* OR program* OR experiment* OR effect* OR impact*

The asterisk allowed for the inclusion of term variations (e.g., singular vs plural).

Databases

Ten databases were systematically searched by three researchers (J.K., T.S., P.S.) for relevant records in December 2017 and again in September 2019. Database names and the number of records retrieved from each database are shown in Table 1. Variation in the number of records retrieved from the different databases is explained by the size and the subject specialization of each database.

Table 1.

Number of records retrieved by database

| Database | Number of records retrieved |

|---|---|

| Cochrane | 182 |

| EBSCO (All Databases) | 234 |

| Ovid (All Databases) | 984 |

| PubMed | 313 |

| Web of Science (All Databases) | 621 |

| Embase | 783 |

| ProQuest (All Databases) | 320 |

| Australasian Medical Index (via Informit) | 0 |

| Emerald | 72 |

| Grand total | 3509 |

| Total after duplicates removed | 1359 |

The combined total of records downloaded from all databases was 3430. All downloaded records were imported into EndNote X9. From the initial records collected, 2071 duplicate records were removed (first by EndNote, then by reviewers T.S. and P.S.), leaving 1359 unique sources.

All downloaded records were imported into Endnote X9. After duplications were removed, two reviewers (T.S., P.S.) reviewed titles and abstracts of the remaining papers were reviewed for eligibility. Any papers that were

not peer-reviewed (e.g., newspapers, theses, or conference proceedings);

not written in English;

not tobacco focused;

not GHW focused;

systematic literature reviews;

cross-sectional studies with only one time point

were excluded.

Longitudinal studies with empirical data that consisted of the following information were included:

Published in peer-review journals;

Published between 2008 and 2019, only studies that were published in the past 10 y were included to ensure the recency of this review;

Reporting detailed information on the formats of GHWs;

Reporting on outcomes pertaining to either: communicating the risk of smoking on health, or the benefits of quitting, or quit intention.

Selected studies were qualified for inclusion considering the operationalization of perceived risk and quit intentions, given the diversity of measurements for each behavioral outcome. Perceived risks were operationalized as thinking about the risks of smoking, perceived likelihood of harm from smoking and identifying that smoking causes tobacco related diseases. Quit intentions, were operationalized as the intention to quit smoking in a certain period of time or the extent to which health warning labels make the person more likely to quit smoking.

Data extraction and coding framework

A coding framework was developed to enable a standardized method for extraction of the following information from qualified records, as shown in Table 2.

Bibliographic information, such as authors, title, and publication year;

Study characteristics, such as study location, study design, and sample size;

Formats of GHWs, such as the size and location of graphics;

Outcome evaluation, such as the effectiveness of GHWs on communicating the risk of smoking on health and the benefits of quitting, as well as quit intentions.

Table 2.

Coding framework

| Construct | Code(s) |

|---|---|

| A. Bibliographic Information | |

| Authors(s) | As stated in article |

| Title | As stated in article |

| Publication year | As stated in article |

| B. Study Characteristics | |

| Study design | 1. Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) or Controlled Clinical Trial (CCT) |

| 2. Quasi Experiment (two or more groups pre and post) | |

| 3. Cohort (one group pre and post) | |

| 4. Interrupted time series (or Longitudinal) | |

| Location | Country, Region |

| Study aim(s) | As stated in article |

| Product | cigarette, e-cigar, shisha, beedis, roll your own, etc. |

| GHWs disclosure formats - Graphics |

Location i. Both the front and back ii. On principal display areas (top, bottom) iii. Package inserts iv. Others Size v. 51% or more vi. Between 31% ~ 50% vii. Less than 30% Colors viii. Black and white ix. Others (specify) Image concept x. Positive outcome focused xi. Negative outcome focused Others – Congruency – whether the image is congruent with the text warnings |

| GHWs disclosure formats - Texts |

Location xii. All sides of a package xiii. Both the front and back xiv. On principal display areas (top, bottom) xv. Package inserts xvi. Others Size xvii. Legible font size xviii. Not legible font size Color xix. Black and white xx. Others (specify) Language Message content xxi. Positive outcome focused xxii. Negative outcome focused Source attribution (specify) |

| Others (specify) | |

| Intervention sample | Sample description (e.g. people aged 18–25, smokers) |

| C. Outcome Evaluation | |

| Outcome measure - Benefits of quitting/Quit intentions | Pre-post changes across different groups |

| Outcome measure - Perceived risk of smoking | Pre-post changes across different groups |

Trained coders (T.S., P.S.) extracted data from each record according to the published details contained in the publication. All of the records were cross checked by at least two independent coders to ensure consistency of data extraction.

Quality assessment

To assess the risk of bias in included studies we applied either the Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies - of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I) [30] or Risk of Bias tool 2 (RoB2) [31] to each study selected into the systematic review. The ROBINS-I tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias in the results of non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI) that compare the health effects of two or more interventions. This tool is highly applicable to the evaluation of GHW label studies because the types of NRSIs that can be evaluated using this tool are quantitative studies estimating the effectiveness (harm or benefit) of an intervention, which did not use randomization to allocate units (individuals or clusters of individuals) to comparison groups. This description applies to the majority of the studies selected into our review. The designs include studies where allocation occurs during the course of usual treatment decisions or peoples’ choices. In our systematic search results, the studies were of NRSI designs and nine papers were RCTs. For those RCTs, a Cochrane developed quality assessment framework – Risk of Bias Ver. 2 (RoB2) was used. RoB2 is a tool used to assess the risk of bias of the intervention effect between two intervention groups (the experimental and comparator group) [23]. This tool is applicable to the evaluation of quantitative GHW label studies ascertaining the effect of adhering to a controlled intervention (i.e. pictorial GHW, text only GHW or no GHW) where individuals were randomly assigned to intervention or comparator groups.

Each study was carefully examined and coded considering all the ways in which it might be put at risk of bias with close reference to the guidelines. Two independent reviewers (T.S., P.S.) coded each study and coding was compared. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved with the help of a third and fourth reviewer (B.P., K.K.).

Results

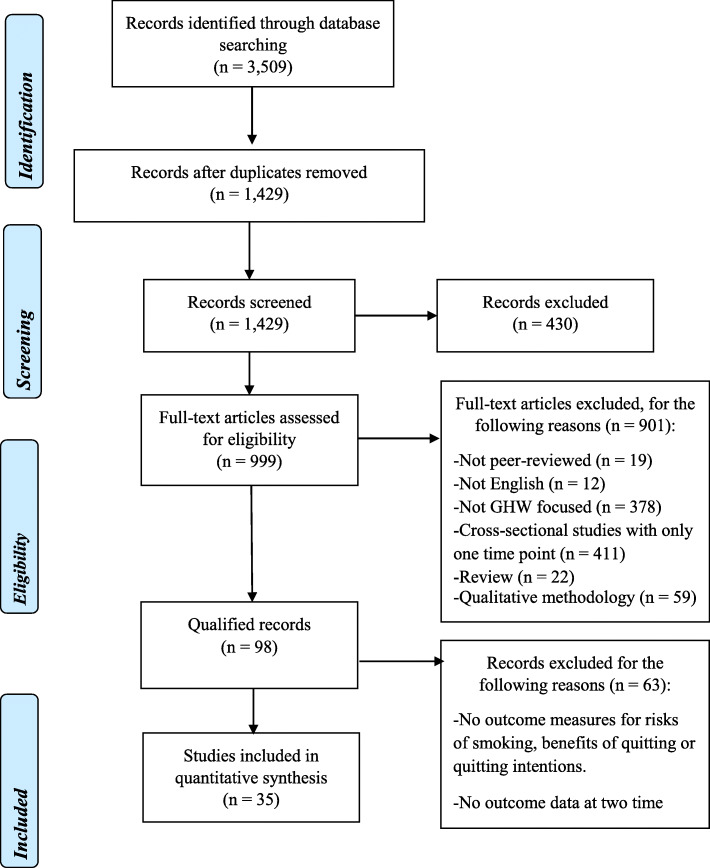

After removing duplicates and ineligible articles, 35 studies met the inclusion criteria, resulting in the sample of qualified records. The PRISMA flow diagram summarizing the exclusion and inclusion process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study Demographics

Overall, 40% of the studies were conducted across multiple countries (n = 14) such as Australia, Canada and Mexico [3, 32, 33], while 60% of interventions were conducted in one country (n = 21). Out of the 35 qualified studies, 63% of interventions were conducted in developed countries (n = 22), 29% in countries in development (n = 10), and 8% in both types of populations (n = 3). Frequently, data across a range of countries were reported in a single study, therefore, the quantity of counties mentioned is higher than the total of 35 studies. Developed countries evaluated include Australia (n = 12) [32, 34], the United States (n = 12) [35, 36], Canada (n = 11) [3, 33], Europe (n = 9) (five in the UK [1, 35], three in Germany [37–39], one in France and the Netherlands [38], and one in Italy [40]. Interventions conducted in countries in development (n = 10) included Asia (n = 6) (five in Malaysia [5, 41], three in Thailand [42, 43], one in China [5], one in India [4] and one in Vietnam [44], Latin America (n = 5) (four in Mexico [45], one in Uruguay [46] and one in Africa (in Mauritius [47]).

Regarding types of tobacco product packages that were tested, 86% of interventions were conducted on generic cigarette packs (n = 30), three were conducted on RYO cigarette packs [41, 43, 48], one was conducted on smokeless tobacco [4] and one was conducted on moist snuff, snus, and e-cigarettes [49]. The intervention group sample sizes varied from 44 [39] to 5991 [4]. Most of the studies were focused on smokers.

Over 70% of interventions were non-randomized designs (n = 26) followed by 26% of randomized interventions (n = 9) [39, 50]. Table 3 summaries the study demographics as well as key findings of included papers.

Table 3.

Study characteristics

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Location | Product | Study design | Sample size | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anshari et al., 2018 | Australia, Canada, Mexico | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 1671 | Over time, pictorial GHWs responses significantly changed in terms of increased noticing pictorial GHWs in Canada and Mexico, increased negative affect in Australia and decreased negative affect in Mexico. |

| CA: 2357 | ||||||

| MX: 2537 | ||||||

| 2 | Borland et al., 2009 | Australia, Canada, UK, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 4111 | AU: all four indicators of impact increased following the introduction of GHW. Findings show partial wear-out of both graphic and text-only warnings, but the Canadian warnings have more sustained effects than UK ones. |

| UK: 4273 | ||||||

| CA: 4305 | ||||||

| 3 | Brewer et al., 2016 | US | Cigarette packs | RCT | 1071 | Smokers who had pictorial GHWs were more likely than those with text-only GHWs to attempt to quit smoking during trial. Pictorial GHWs increased forgoing, intentions to quit, negative emotional reactions, thinking about the harms, and conversations about quitting. |

| 4 | Brewer et al., 2019 | US | Cigarette packs | RCT | 2149 | Pictorial GHWs increased attention to, reactions to, and social interactions about warnings. However, pictorial GHWs changed almost no belief or attitude measures. Mediators of the impact of pictorial GHWs included harms of smoking and intentions to quit. |

| 5 | Cho et al., 2018 | Australia, Canada, Mexico, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 1036 | Perceived risks significantly increased over time (AU & CA), where new more prominent GHWs included diseases that had not been described on prior GHWs. In MX, where pictures were changed but the diseases they described did not, perceived risks also increased. |

| CA: 1190 | ||||||

| MX: 1166 | ||||||

| 6 | Durkin et al., 2015 | Australia | Cigarette packs and roll-your-own (RYO) packs | Longitudinal | N (weighted) = 5441 | Plain Packaging (PP) early transition respondents showed significantly greater increases in stopping themselves from smoking and quit attempts. PP late transition respondents showed greater increases in intentions to quit and pack concealment. PP first year respondents showed higher levels of pack concealment, more premature stubbing and higher quit attempts. |

| 7 | Elton-Marshall et al., 2015 | China, Malaysia | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | 2883 | Significant changes prior to the new GHW introduction in noticing and reading GHWs. Compared to Malaysia, text-only GHWs in China led to a significant change in only two of six key indicators of GHW effectiveness: forgoing and reading the GHWs. The change to pictorial GHWs in Malaysia led to significant increases in five of six indicators (noticing, reading, forgoing, avoiding, thinking about quitting). |

| 8 | Fathelrahman et al., 2010 | Malaysia | Cigarette packs | RCT | 70 | Exposure to pictorial GHWs increased awareness of risks, behavioral response and quitting intention. Interest in quitting increased significantly more in those exposed to pictorial GHWs. |

| 9 | Fathelrahman et al., 2013 | Malaysia, Thailand | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Pre GHW: 1018 | Multivariate predictors of “interest in quitting” were comparable across countries, but predictors of quit attempts varied. In both countries, cognitive reactions, forgoing and baseline knowledge were positively associated with interest in quitting at that wave. Thailand only: cognitive reactions, forgoing a cigarette” and interest in quitting were positively associated with quit attempts over the following inter-wave interval. |

| Post GHW: 803 | ||||||

| 10 | Glock & Kneer, 2009 | Germany | Cigarette packs | RCT | 60 | There was no major effect from the intervention condition, and after being confronted with warning labels, smokers decreased their perceived smoking-related risk. |

| 11 | Gravely et al., 2016a | Uruguay | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Wave 2: 1294 | All indicators of GHW effectiveness increased significantly, including salience, thinking about risks, thinking about quitting, avoiding looking, and stopping from having a cigarette ‘many times’. |

| Wave 3: 452 | ||||||

| 12 | Gravely et al., 2016b | India | Smokeless tobacco | Longitudinal | Scorpion GHW: 5991 | GHW label change in India from symbolic (scorpion) to pictorial GHWs did not result in significant increases on any of the GHW outcome indicators. |

| New pictorial GHW: 4634 | ||||||

| 13 | Green et al., 2014 | Mauritius | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Pre (w1): 598 | All indicators of warning effectiveness (salience, cognitive, and behavioral reactions) and the Label Impact Index (weighted combination of 4 indicators) increased significantly between Waves 1 and 2. However, between Waves 2 and 3, there was a significant decline in the proportion of smokers who reported “avoiding looking” at labels. |

| Post 12 months (w2): 555 | ||||||

| 14 | Green et al., 2019 | Canada | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | 5863 | Adding messages to GHWs significantly increased awareness that smoking causes blindness and bladder cancer. Adding the warning that nicotine causes addiction did not significantly impact smokers’ awareness. Removing messages was shown to decrease awareness that cigarette smoke contains carbon monoxide and smoking causes impotence. |

| 15 | Hall et al., 2018 | US | Cigarette packs | RCT | 1071 | Pictorial GHWs increased negative affect, message reactance and quit intentions, but not perceived risk. Negative affect mediated the impact of pictorial warnings on quit intentions. |

| 16 | Hitchman et al., 2014 | Canada, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | CA: 5309 | The effectiveness of both pictorial GHWs (CA) and text-only GHWs (US) warnings declined significantly over time. Pictorial GHWs showed greater declines in effectiveness than the text-only warnings. Despite the greater decline in pictorial GHWs, they were significantly more effective than the text-only GHWs throughout the study. |

| 17 | Kasza et al., 2017 | Australia, Canada, UK, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | CA: 4884 | Between 2002 and 2015, smokers’ concern for personal health was the most frequently endorsed reason for thinking about quitting in the UK, Canada, the US and Australia, and across all reasons to quit smoking, concern for personal health had the strongest association with making a quit attempt at follow-up wave. |

| AU: 4482 | ||||||

| 18 | Kennedy et al., 2012 | Australia, Canada, UK, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 3151 | After the introduction of the blindness warning, Australian smokers were more likely than before the blindness warning to report that they know that smoking causes blindness. In Australia, smokers aged over 55 years were less likely than those aged 18 to 24 to report that smoking causes blindness. |

| 19 | Li et al., 2015 | Australia, Canada, UK | Cigarette packs | Cohort | AU (t1): 1801 | The impact of warnings declined over time in all three countries. Having two rotating sets of warnings does not appear to reduce wear-out over a single set of warnings. Warning size may be more important than warning type in preventing wear-out, although both probably contribute interactively. |

| AU (t2): 1104 | ||||||

| 20 | Li et al., 2016 | Malaysia, Thailand | Cigarette packs and RYO packs | Longitudinal | TH (w3): 2465 | The main outcome was subsequent quit attempts. Following the implementation of GHWLs in Malaysia, reactions increased, in some cases to levels similar to the larger Thai warnings, but declined over time. In Thailand, reactions increased following implementation, with no decline for several years, and no clear effect of the small increase in warning size. Reactions, mainly cognitive responses, were consistently predictive of quit attempts in Thailand, but this was only consistently so in Malaysia after the change to GHWLs. |

| Th (w5): 2132 | ||||||

| MY (w2): 1640 | ||||||

| MY (w4): 2045 | ||||||

| MY (w6): 2000 | ||||||

| 21 | Mannocci et al., 2019 | Italy | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Pre: 788 | Significant increases of knowledge of health risk after pictorial GHWs introduction in a short period (8–18 months). The awareness about gangrene, blindness, premature labour and erectile dysfunction registered the higher increase before and after law implementation. |

| Post: 455 | ||||||

| 22 | Mays et al., 2014 | US | Cigarette packs | RCT | 740 | Gain-framed warnings generated significantly greater motivation to quit among smokers with high perceived risks compared with smokers with low perceived risks. Among smokers with high perceived risks, gain-framed messages were superior to loss-framed messages. |

| 23 | McQueen et al., 2015 | US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | 202 | Participants reported low avoidance and consistent use of the stickers. Smokers consistently paid more attention to graphic than text-only labels. Only 5 of the 9 GHWs were significantly associated with greater thoughts of health risks. Thinking about quitting and stopping smoking did not differ by label. |

| 24 | Nagelhout et al., 2016 | France, Germany, Netherlands | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | UK: 1643 | Salience decreased between the surveys in France and showed a non-significant increase in the UK, cognitive responses increased in the UK and decreased in France, forgoing cigarettes increased in the UK and decreased in France, and avoiding warnings increased in France and the UK. |

| FR: 1540 | ||||||

| 25 | Ngan et al., 2016 | Vietnam | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Wave 1: 1462 | Two years after implementation, salience of the pictorial GHWs was higher than one year after implementation. The proportion of respondents who tried to avoid noting pictorial GHWs decreased from 35% in wave 1 to 23% in wave 2. However, avoidance increased 1.5 times the odds of presenting quit intention compared to those respondents who did not try to avoid looking/thinking about the pictorial GHWs |

| Wave 2: 1509 | ||||||

| 26 | Nicholson et al., 2017 | Australia | Cigarette packs | Cohort | 642 | Forgoing increased significantly only for those first surveyed prior to the introduction of plain packaging (PP); however, there were no significant interactions between forgoing and the introduction of new and enlarged graphic warning labels on PP in any model. |

| 27 | Osman et al., 2016 | Mexico | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | 1340 | All GHW responses increased over time, except putting off smoking. |

| 28 | Parada et al., 2017 | US | Cigarette packs | RCT | Intervention: 1071 | Smokers in the intervention (pictorial GHWs) group thought more about the warning message and harms of smoking, reported higher levels of fear due to warnings, experienced more negative affect, expressed more intention to quit, and forewent smoking cigarettes more than participants in the control group. |

| Control: 1078 | ||||||

| 29 | Partos et al., 2013 | Australia, Canada, UK, US | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 576 | Reporting that GHWs make quitting over time ‘a lot’ more likely (compared with ‘not at all’ likely) was associated with a lower likelihood of relapse 1 year later and this effect remained robust across all models tested, increasing in some. Reporting that GHWs make you more likely to remain smoking free was strongly correlated with reporting that GHWs make you think about health risks. |

| CA: 478 | ||||||

| UK: 512 | ||||||

| 30 | Popova & Ling, 2014 | Canada | Moist snuff, snus, and e-cigarettes | RCT | 76 | Pictorial GHWs increased perceived harm of moist snuff and e-cigarettes. Current warning label and pictorial GHW significantly lowered positive attitudes towards e-cigarettes. |

| 31 | Schneider et al., 2012 | Germany | Cigarette packs | RCT | 44 | Pictorial GHWs were associated with a significantly higher motivation to quit. A pictorial GHW was also associated with higher fear intensity. The effect of warnings appears to be independent of nicotine dependence and self-affirmation. |

| 32 | Swayampakala et al., 2014 | Australia, Canada, Mexico | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | AU: 1001 | Smokers in countries with GHWs describing specific health risks had greater awareness and knowledge of those specific health risks (with only few exceptions) compared to smokers in countries that do not include the same GHWs health risks (e.g., risk of blindness in Australia, but not Mexico). |

| CA: 1001 | ||||||

| MX: 1000 | ||||||

| 33 | White et al., 2008 | Australia | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | 2432 | Attention to and processing of warning labels increased from T1 to T2. Smokers considered quitting more at follow-up (T2). |

| 34 | Yong et al., 2013 | Thailand, Malaysia | Cigarette packs and RYO packs | Longitudinal | TH (w1): 3067 | After GHW change smokers’ awareness, cognitive, and behavioral reactions increased, with cognitive and behavioral effects sustained at follow-up (Thailand). Compared to smokers who smoke generic cigarettes, smokers of RYO reported lower salience but greater cognitive reactions to the new pictorial GHWs. |

| TH (w2): 1986 | ||||||

| 35 | Yong et al., 2016 | Australia | Cigarette packs | Longitudinal | Pre: 1104 | Attentional orientation towards GHWs and reported frequency of noticing warnings increased significantly after the policy change, but not more reading. Smokers also thought more about the harms of smoking and avoided the GHWs more after the policy change, but frequency of forgoing cigarettes did not change. |

| Post: 1093 |

Quality assessment

Two tools were used to assess study quality. These are presented in turn. The ROBINS-I tool was applied to 26 of the 35 included studies due to the NRSI nature of the studies. The majority (96.2%) of the 26 studies were found to be at moderate risk of bias in at least one of the domains. The moderate overall bias was attributed mostly to ‘confounding’ variables. Confounding was predominately due to introduction of enhanced pictorial health warnings [3, 35], other marketing campaigns and smoking policies (e.g. price increases) during the course of the longitudinal study [34, 48], or due to variance in smoking quantity amongst participants [32, 38, 51]. One study was found to be serious in at least one domain [1]. Partos, Borland [1] was rated as serious in the ‘selection of participants’ domain because selection into the study was based on self-report of quitting smoking and the main outcome measures were quit-related with no note on whether selection bias was taken into account. Over half of the studies (18 out of 26 studies) were at low risk of bias due to missing data. Many studies had almost complete outcome data or used suitable data analysis methods to minimise the bias from missing data. Table 4 summarizes risk of bias ratings for individual studies.

Table 4.

Quality assessment

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Risk of bias due to confounding | Risk of bias in selection of participants | Risk of bias in classification of interventions | Risk of bias due to deviations from intended intervention | Risk of bias due to missing data | Risk of bias in measurement of outcomes | Risk of bias in selection of the reported result | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anshari et al., 2018 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 2 | Borland et al., 2009 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 5 | Cho et al., 2018 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 6 | Durkin et al., 2015 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 7 | Elton-Marshall et al., 2015 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| 9 | Fathelrahman et al., 2013 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate |

| 11 | Gravely et al., 2016a | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 12 | Gravely et al., 2016b | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 13 | Green et al., 2014 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 14 | Green et al., 2019 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 16 | Hitchman et al., 2014 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 17 | Kasza et al., 2017 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| 18 | Kennedy et al., 2012 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 19 | Li et al., 2015 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | NI | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 20 | Lin et al., 2016 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 21 | Mannocci et al., 2019 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | NI | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 22 | Mays et al., 2014 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 24 | Nagelhout et al., 2016 | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 25 | Ngan et al., 2016 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 26 | Nicholson et al., 2017 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 27 | Osman et al., 2016 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| 29 | Partos et al., 2013 | Moderate | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Serious |

| 32 | Swayampakala et al., 2014 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 33 | White et al., 2008 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 34 | Yong et al., 2013 | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| 35 | Yong et al., 2016 | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

RoB2

The RoB2 tool was applied to accurately address bias in nine studies that were identified as RCTs. Six studies were judged to be at a low risk of bias among all domains [37, 39, 49, 50, 52, 53]. Two studies were judged to have some concerns in at least one domain [36, 54]. Parada, Hall [36] was low in all domains except for bias due to missing outcome data. One paper [36] stated “Proportions of participants who completed the follow-up surveys at each of the follow up weeks included 86% at week 1, 82% at week 2, 81% at week 3 and 84% at week 4” (p 878). No information regarding how missing data was handled or if the missing data biased the final result was provided lowering assessment scores. Fathelrahman, Omar [54] was rated as some concerns in effect of assignment to interventions but was low in all other domains. There was unclear information on whether participants were blinded to the intervention because “In both groups, participants were given the packs all at the same time and instructed to take a few minutes to examine them” (p. 4091). In addition, research staff were aware of the intervention that was assigned to participants as they assigned the cigarette packaging.

One study was judged to be a high risk of bias overall as a result of a high risk from the randomization process [55]. There was no description of the randomization process. Furthermore, there were substantial differences between intervention group sizes, compared with the intended allocation ratio. Group differences were not examined “because of small cell sizes, we did not examine statistical differences in socio-demo- graphics by study condition” (p. 787). For all other domains, McQueen, Kreuter [55] was judged to be at low risk of bias. Table 5 presents details on RoB2 assessment applied to randomized controlled trials included in this review.

Table 5.

Quality assessment

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Risk of bias arising from the randomization process | Risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions (effect of assignment to intervention) | Risk of bias due to missing outcomes data | Risk of bias in measurement of the outcome | Risk of bias in selection of the reported result | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Brewer et al., 2016 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 4 | Brewer et al., 2019 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 8 | Fathelrahman et al., 2010 | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| 10 | Glock & Kneer, 2009 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 15 | Hall et al., 2018 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 23 | McQueen et al., 2015 | High | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| 28 | Parada et al., 2017 | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| 30 | Popova & Ling, 2014 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| 31 | Schneider et al., 2012 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

RoB2

GHW formats

GHWs vary in formatting according to the size of image, placement on the package, message framing, congruence, colour, text size, message attribution (source), and the inclusion of Quitline information. The included studies described warning formats for images, with sizes ranging from 30 to 90% coverage of cigarette packaging. Formats in front of the cigarette package varied from 30% (n = 13) [35, 56], 50% (n = 15) [41, 50] to 75% (n = 8) [32, 34], and included other sizes (n = 10) between 40% [5] and 90% [33]. Formats on the back of the cigarette package varied from 30% (n = 1) [37], 50% (n = 14) [41, 50] to 75% (n = 4) [33, 57]. Once again other sizes (n = 7) such as 40% [38], 80% [46], 90% (n = 13) [34, 48] and 100% (n = 3) were described [3, 32, 33].

In regard to the location of the images on the cigarette pack, 77% of the studies (n = 27) evaluated front and back image formats. Twelve studies evaluated other location formats including only the front image (n = 5) [39, 54], front, back & sides (n = 1) [32], front, back & package inserts (n = 4) [3, 33, 47, 57], and no location on the pack (GHW images shown on a screen) (n = 2) [37, 49].

In regard to message framing, 91% of the studies (n = 32) evaluated negatively framed message formats. Negative framing refers to fear-based images, for instance, a graphic photo of a severe disease (e.g. mouth cancer) in Australian GHWs [35]. Nine studies evaluated other types of message framing including symbolic messages (n = 3), for example, an image of a scorpion to communicate danger for Indian GHWs on smokeless tobacco [4], or an empty cradle paired with the message ‘tobacco hurts everyone’ in Canadian GHWs [58], and mixed (n = 6) framing where negative and symbolic GHW formats in the same groups [3, 32, 33, 47, 57, 59] were evident.

GHW formats where the message was presented in images and text communicating a consistent, aligned message is a key factor for GHW effectiveness. One study evaluated an incongruent message format, notably a scorpion GHW that was not congruent with the message ‘tobacco kills’ that was implemented when the GHW was changed in India [4]. Likewise, 94% of the studies (n = 33) evaluated color GHW image formats. Only two studies evaluated black and white formats from RYO cigarette packs in Thailand [41, 43].

In regards to text formats that accompany GHWs, text size varies from approximately 10% of the package, for instance in Malaysia [5] and the UK [1], to 100% of the back of the package in the case of Mexico [3]. Fifty-four percent of studies evaluated formats that displayed a text source of attribution (n = 19). For instance, the ‘Health Authority Warning’ source that appeared in 2006–2012 Australian GHWs (n = 9) [34, 35], Health Canada (n = 8) [32, 47], and US Department of Health and Human Services (US HHS) (n = 5) [55, 60]. 46% of studies evaluated formats that did not display any source of attribution (n = 16) [42, 46]. Forty-three percent of studies tested formats that displayed a quit line number (n = 15), for instance, Australian GHW formats before and after plain packaging policy [34]. Finally, 37% of studies tested formats that did not display any quit line number (n = 13), such as Uruguay [46], and 17% of studies tested both formats (n = 6). Table 6 summarizes the formatting features of included studies.

Table 6.

Formatting of GHWs

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Group | Graphic: Size (front) % | Graphic: Size (back) % | Graphic: Location | Graphic: Image concept1 | Graphic: congruency2 | Graphic: Colour | Text: Size % | Text: Location | Text: Source attribution | Text only GHW | Quitline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anshari et al., 2018 | Australia | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes |

| Canada | 75 | 75 | Front, back & sides | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 37 | Front, back & sides | Health Canada | No | Yes | ||

| Mexico | 30 | 100 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 100 | Back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 2 | Borland et al., 2009 | Australia (Wave2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No |

| Australia (Wave5) | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes | ||

| UK | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No | ||

| Canada | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 20 | Front & back | Health Canada | No | No | ||

| 3 | Brewer et al., 2016 | Pictorial (Pre & Post) | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 12.5 | Front & back | US HHS | No | No |

| 4 | Brewer et al., 2019 | Complete sample | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | US HHS | No | No |

| 5 | Cho et al., 2018 | Australia | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes |

| Canada | 75 | 75 | Front, back & package inserts | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 37 | Front, back & package inserts | Health Canada | No | Yes | ||

| Mexico | 30 | 100 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 100 | Back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 6 | Durkin et al., 2015 | Pre PP | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| Late transition & Post PP | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 7 | Elton-Marshall et al., 2015 | Malaysia (Pre) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No |

| Malaysia (Post) | 40 | 60 | Front & back | Negative | NA | Colour | 10 | Front | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 8 | Fathelrahman et al., 2010 | Complete sample | 60 | NA | Front | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 40 | Front | No source | No | Yes |

| 9 | Fathelrahman et al., 2013 | Pre GHW | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No |

| Post GHW | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 10 | Front | No source | No | No | ||

| 10 | Glock & Kneer, 2009 | Complete sample | 30 | 30 | No location on pack (screen) | Negative | Congruent | Colour | NA | NA | NA | No | No |

| 11 | Gravely et al., 2016a | Wave 2 | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Symbolic | NA | Colour | 30 | Front | No source | No | No |

| Wave 3 | 80 | 80 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 30 | Front & back | No source | No | No | ||

| 12 | Gravely et al., 2016b | Scorpion GHW | 40 | NA | Front | Symbolic | Incongruent | NA | NA | Front | NA | No | NA |

| New pictorial GHW | 40 | NA | Front | Negative | Congruent | Colour | NA | Front | NA | No | NA | ||

| 13 | Green et al., 2014 | Pre pictorial GHW (Wave1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 | NA | NA | Yes | NA |

| Post 12 months (Wave2) | 60 | 70 | Front & back | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 65 (side) | Front & back | No source | No | No | ||

| 14 | Green et al., 2019 | Complete sample | 75 | 90 | Front, back & package inserts | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 37 | Front, back & package inserts | Health Canada | No | Yes |

| 15 | Hall et al., 2018 | Complete sample | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | US HHS | No | YES |

| 16 | Hitchman et al., 2014 | Canada | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Symbolic | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | Health Canada | No | No |

| 17 | Kasza et al., 2017 | Canada (Wave1) | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | Health Canada | No | No |

| Canada (Wave9) | 75 | 75 | Front, back & package inserts | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 37 | Front, back & package inserts | Health Canada | No | Yes | ||

| Australia (Wave1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | No | ||

| Australia (Wave9) | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 18 | Kennedy et al., 2012 | Australia (Waves 1–7) | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| 19 | Li et al., 2015 | Australia | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| 20 | Li et al., 2016 | Thailand (Wave3) | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Black & white | 10 | Front & back | No source | No | No |

| Thailand (Wave5) | 55 | 55 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | black & white | 10 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| Malaysia (Wave2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 70 | Sides | NA | Yes | No | ||

| Malaysia (Wave4 and6) | 40 | 60 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 10 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 21 | Mannocci et al., 2019 | Italy (Post) | 65 | 65 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 50 | Sides | No source | No | No |

| 22 | Mays et al., 2014 | Intervention | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | NA | Colour | NA | Front & back | US HHS | No | Yes |

| 23 | McQueen et al., 2015 | Graphic condition | 50 | NA | Front | Negative | Congruent | Colour | NA | Front | US HHS | No | Yes |

| 24 | Nagelhout et al., 2016 | UK (Pre) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 (front), 40 (back) | 3 | NA | Yes | NA |

| UK (Post) | 43 | 53 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 10 | Front & back | No source | No | No (only 1/14 has Quitline) | ||

| FR (Pre) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 (front), 40 (back) | 3 | NA | Yes | NA | ||

| FR (Post) | 0 | 40 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 20 | Front | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 25 | Ngan et al., 2016 | Wave 1 & 2 | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 12 | Front & back | No source | No | No |

| 26 | Nicholson et al., 2017 | Pre PP | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| Post PP | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 27 | Osman et al., 2016 | Complete sample | 30 | 0 | Front | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 100 | Back | No source | No | Yes |

| 28 | Parada et al., 2017 | Pictorial GHW (Waves 1–4) | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | NA | Front & back | No source | No | No |

| 29 | Partos et al., 2013 | AU | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| CA | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | Health Canada | No | No | ||

| UK | 30 | 40 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 10 | Front | No source | No | No | ||

| 30 | Popova & Ling, 2017 | NA | NA | No location on pack (screen) | Negative | Congruent | Colour | NA | No location on pack (screen) | No source | No | No | |

| 31 | Schneider et al., 2012 | Pictorial GHW | 45 | 0 | Front | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 20 | Front | No source | No | No |

| 32 | Swayampakala et al., 2014 | AU (Pre) | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| AU (Post) | 90 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 30 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| CA (Pre) | 75 | 75 | Front & back | Mixed | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | Health Canada | No | Yes | ||

| CA (Post) | 75 | 75 | Front, back & package inserts | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front, back & package inserts | Health Canada | No | Yes | ||

| MX (Pre-Post) | 30 | 100 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 100 | Back | No source | No | Yes | ||

| 33 | White et al., 2008 | AU 2006 GHW | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| 34 | Yong et al., 2013 | TH (Wave1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 33 | Front & back | NA | Yes | NA |

| TH (Wave 3) | 50 | 50 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | black & white | 12 | Front & back | No source | No | No | ||

| 35 | Yong et al., 2016 | Pre PP | 30 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 15 | Front & back | Health authority warning | No | Yes |

| Post PP | 75 | 90 | Front & back | Negative | Congruent | Colour | 25 | Front & back | No source | No | Yes |

1Positive image concept refers to graphics portraying the benefits of quitting smoking while negative images show the harmful effects of smoking.

2Congruency refers to GHW formats where the message is presented in images and text communicating a consistent, aligned message

Perceived harm outcomes

Thirty-four studies measured the impact of changes to GHWs on perceived risk using various measures across studies and countries. To be noted that the measurement of perceived risks is substantially inconsistent across included studies. In eight studies, a single measure of “To what extent, if at all, do the health warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking” (or slight variation of wording) was used to measure the perceived risk of smoking [1, 5, 41, 45, 46, 54, 55, 58, 59]. Seven studies used combined “cognitive response” measures [4, 34, 35, 38, 42, 43, 61]. See the Table 7 for the detailed measures. The perceived risk measure of “extent to which the warnings made the respondent think about the health risks of smoking” was often combined with the “if the health warnings made them more likely to quit” to cognitive reactions. Other commonly used measures were perceived likelihood of harm which were used in three studies [50, 52, 53] and identifying that smoking causes tobacco related diseases was used in six studies [3, 33, 37, 47, 56, 62]. A brief summary of the findings is presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Perceived harm outcomes

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Group | Perceived risk | OR or Beta | Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | |||||

| 1 | Anshari et al., 2018 | Australia | 0.22 (0.03 to 0.40) | 0.36 (0.09 to 0.63) | NA | Negative affect: “How much does this warning make you feel worried about the health risks of smoking?” |

| Canada | 0.06 (−0.08 to 0.20) | 0.03 (−0.23 to 0.28) | NA | |||

| Mexico | 0.00 (−0.14 to 0.15) | −0.25 (−0.47 to 0.02) | NA | |||

| 2 | Borland et al., 2009* | Australia | 1.68 | 2.04 | NA | Cognitive responses combined two questions: “Extent to which the warnings both made the respondent think about the health risks of smoking” and “made them more likely to quit smoking” |

| UK | 1.95 | 1.81 | NA | |||

| Canada | 1.93 | 1.84 | NA | |||

| 3 | Brewer et al., 2016 | NA | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | NA | Combined three perceived harm questions: “What is the chance that you will one day get cancer if you continue to smoke cigarettes?”, “What is the chance that you will one day get heart disease if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” and “What is the chance that you will one day get a permanent breathing problem if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” |

| 4 | Brewer et al., 2019 | NA | 0.04 (−0.04, 0.13) | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.11) | NA | Perceived likelihood of harm from smoking combined 3 questions: “What is the chance that you will one day get cancer if you continue to smoke cigarettes?”, “What is the chance that you will one day get heart disease if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” and “What is the chance that you will one day get a permanent breathing problem if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” |

| 5 | Cho et al., 2018 | Australia | 1.14 | 1.22 | NA | “Indicate which illnesses, if any, are caused by smoking cigarettes (emphysema, heart attacks, bladder cancer, blindness, impotence in male smokers, gangrene, hepatitis, and diseases that lead to amputation)” and ‘Their own chance of getting the disease in the future to the chance of a nonsmoker if they continue to smoke the amount that they currently do’ |

| Canada | 1 | 1.22 | NA | |||

| Mexico | 1.25 | 1.26 | NA | |||

| 7 | Elton-Marshall et al., 2015 | NA | 6.90% | 11.80% | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings on cigarette packs make you more likely to think about the health risks (health danger) of smoking?” |

| 8 | Fathelrahman et al., 2010 | NA | 8 (11.6%) | 20 (29.0%) | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings on the cigarette pack designs make you more likely to quit smoking” |

| 9 | Fathelrahman et al., 2013 | NA | 3.6 (1.9) | 3.8 (2.0) | NA | Cognitive reactions combined two measures: “thinking about health risk because of them (think-harm)” and thinking about quitting because of them (think-quit)” |

| 10 | Glock & Kneer, 2009 | NA | 5.50 (2.05) | 4.67 (1.63) | NA | Pre health warning viewing: Six smoking-related and six non-smoking-related diseases were rated between 0 (no risk of developing disease) and 9 (highest risk of developing disease). Post health warning viewing: rated another 12 diseases under the same conditions |

| 11 | Gravely et al., 2016a | NA | 31.5% | 43.3% | OR: 1.66 | “To what extent do the health warnings make you think about the dangers from smoking?” |

| 12 | Gravely et al., 2016b | NA | 15.0 (95% CI 11.9; 18.8) | 17.5 (95% CI 12.1; 24.6) | NA | Cognitive reactions two questions: “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on smokeless tobacco packages make you more likely to think about the health risks (health danger) of using it?” and “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on smokeless tobacco packages make you more likely to quit using it?” |

| 13 | Green et al., 2014 | NA | 24.50% | 41.80% | OR: 2.47 (95% CI = 1.87–3.26) | “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking” |

| 14 | Green et al., 2019 | Blindness | 14.70% | 36.70% | NA | “based on what you know or believe, does smoking cause (stroke, impotence, bladder cancer and blindness)” Note: blindness, bladder cancer and addiction were chosen because they were the new messages added to health warning labels |

| Bladder Cancer | 26.80% | 44.00% | NA | |||

| Addiction | 90.50% | 89.60% | NA | |||

| 15 | Hall et al., 2018 | NA | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.55 (0.63) | NA | Perceived likelihood of harm combined 3 questions: “What is the chance that you will one day get heart disease if you continue to smoke cigarettes?”, “What is the chance that you will one day get cancer if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” and “What is the chance that you will one day get a permanent breathing problem if you continue to smoke cigarettes?” |

| 16 | Hitchman et al., 2014* | NA | NA | NA | Log OR: −0.320 (×2 = 5.45) | “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking” |

| 17 | Kasza et al., 2017 | Canada | NA | NA | OR: 1 (CI 1.00 to 1.01) | Concern/ risk reasons: “concern for personal health”, “setting example for children” and “concern for health of others” |

| Australia | NA | NA | OR: 1.01 (CI 1.00 to 1.01) | |||

| 18 | Kennedy et al., 2012 | Australia (Waves 1–7) | 50.1 | 69.5 | NA | ‘I am going to read you a list of health effects and diseases that may or may not be caused by smoking cigarettes. Based on what you know or believe.’ This statement was followed by possible health effects, including, ‘does smoking cause blindness?’ |

| Australia (Wave 8) | 69.5 | 57.5 | ||||

| 19 | Li et al., 2015 | NA | 2.1 | 1.9 | NA | Cognitive response combined 3 questions: “made them think about the health risks of smoking”, “made them more likely to quit smoking” and “if ‘warning labels on cigarette packages’ motivated them to think about quitting in the past 6 months” |

| 20 | Li et al., 2016 | Thailand | 0.49 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.06) | NA | Cognitive response combined 2 questions: “made them think about the health risks of smoking” and “made them more likely to quit smoking” |

| Malaysia (Waves 2–4) | 0.07 (0.06) | 1.01 (0.06) | NA | |||

| Malaysia (Waves 4–6) | 1.01 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | NA | |||

| 21 | Mannocci et al., 2019 | NA | 11.6 (2.5) | 14.6 (1.8) | NA | “Identify tobacco related illnesses (from a list of 20 diseases)” |

| 22 | Mays et al., 2014 | NA | 2.2 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.3) | NA | Perceptions of warnings “warnings convey risks” |

| 23 | McQueen et al., 2015 | NA | 146 (79%) | 158 (86%) | NA | “Made them think about the health risks of smoking” |

| 24 | Nagelhout et al., 2016 | UK | NA | NA | OR: 1.34 | Cognitive responses combined 3 questions: “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking?”, “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?” and “In the past 6 months, have warning labels on cigarette packages led you to think about quitting?” |

| France | NA | NA | OR: 0.7 | |||

| 25 | Ngan et al., 2016 | NA | 12.7 | 18.8 | NA | “Do you worry about the health consequences of smoking?” |

| 26 | Nicholson et al., 2017 | NA | 35 | 38 | NA | “Very worried that smoking will damage your health in future” |

| 27 | Osman et al., 2016 | NA | NA | NA | b = 0.23, SE = 0.03, p < .001 | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings make you think about the health risks of smoking?” |

| 28 | Parada et al., 2017* | NA | 3.2 (mean) | 3.1 | NA | two questions: “In the last week, how often did you think about the harm your smoking might be doing to you?” and “In the last week, how often did you think about the harm your smoking might be doing to other people?.” |

| 29 | Partos et al., 2013* | Australia (Waves 4–6) | 1.89 | 2.42 | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking” |

| Canada (Waves 2–6) | 2.46 | 2.4 | NA | |||

| UK (Waves 2–6) | 2.49 | 2.07 | NA | |||

| 30 | Popova & Ling, 2014 | NA | 6.86 | 7.57 | NA | Two questions: ‘In your opinion, how harmful is … (moist snuff, snus, e-cigarettes) to general health?’ and ‘In your opinion, to what extent does … cause cancer?’ |

| 31 | Schneider et al., 2012 | NA | NA | NA | 18.59 (6.31) | Motivation to quit was assessed with four items: What extent the warnings induced them to: “consider ceasing their cigarette consumption”, “consider reducing their cigarette consumption”, “think about the health risks associated with smoking” and “refrain from smoking a cigarette at the moment” |

| 32 | Swayampakala et al., 2014 | Australia | 62.83 | 65.5 | NA | “To the best of your knowledge, indicate which illness (emphysema, heart attacks, bladder cancer, blindness, impotence in male smokers, gangrene and hepatitis (non-smoking related disease), if any, are caused by smoking cigarettes?” Note: percentages of the six risks were averaged for pre and post result |

| Canada | 56.5 | 61 | NA | |||

| Mexico | 55.5 | 55.3 | NA | |||

| 33 | White et al., 2008 | Experimental smoker | 69.6 | 79 | NA | Agreed or disagreed that smoking caused a number of different illnesses or harms (disease in toes and fingers, mouth cancer, clogs arteries, emphysema, leading cause of death). Note: percentages of the five risks were averaged for pre and post result |

| Established smoker | 67.4 | 78.4 | NA | |||

| 34 | Yong et al., 2013 | NA | 30.9 (2.14) | 48.3 (2.16) | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings make you think about the health risks (health danger) of smoking?” |

| 35 | Yong et al., 2016 | NA | 1.82 | 1.95 | NA | Cognitive reactions combined 3 questions: “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking?”; “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?”; “In the past 6 months, have warning labels on cigarette packages led you to think about quitting?”. |

*Results generated online from web plot digitize

Twenty-four studies showed an increase in perceived harm over time after the implementation of GHWs [3, 5, 34, 50, 59]. Gravely, Fong [46] reported an increase of perceived risk between pre-policy wave 2 (31.5%) and post-policy wave 3 (43.3%). Similarly, Elton-Marshall, Xu [5] and Fathelrahman, Li [42] showed an increase in perceived risk from pre-policy (6.90%) and (M = 3.6, SD = 1.9) and post-policy (11.80%) and (M = 3.8, SD = 2.0) respectively, in Malaysia. However, Li, Fathelrahman [43] showed that whilst there was an increase in perceived harm in Malaysia from pre to post-policy (M = 0.07, SD = 0.06); M = 1.01, SD = 0.06), there was a continued decrease in perceived harm over the years after implementation of GHW (M = 0.47, SD = 0.06). It is noteworthy that all studies that increased perceived risks have GHWs that are 50% and greater, and most of them have credible sources listed next to the warning messages.

Furthermore, the remaining 10 studies found a decrease in perceived harm over the period of the study. As briefly introduced above, a further six studies showed a decrease over a number of years after policy implementation of graphic health or improved graphic [1, 32, 35, 58, 61, 62]. As found in Borland, Wilson [35], Canada in wave 1 had implemented its GHWs and over the four survey waves, the measure of perceived harm decreased from 1.93 (response strength) to 1.84. Hitchman, Driezen [58] confirmed that there was a decrease (OR: − 0.320) in the effectiveness of Canada’s GHWs over the period 2003–2011. Likewise, similar results were found in Australia with Kennedy, Spafford [62], investigating the impact of blindness tobacco warning labels, finding that 69.5% of Australians were aware of the risk that smoking causes blindness, however 3 y later that decreased to 57.5% of Australians. The wear-out effects seem to be evident regardless of GHW formats.

Three studies found that GHWs had a negative impact on perceived risk [36, 37, 52]. All of these studies had short exposure periods with Brewer, Parada [52] and Parada, Hall [36] only testing pre and post exposure to health warnings. Brewer, Parada [52] decreased perceived risk from 0.04 to 0.03 over the period of the study and similarly Parada, Hall [36] showed the same trend of perceived risk decreasing from 3.2 to 3.1 over the course of the four weeks. No clear conclusions can be drawn about GHW formats in relation to perceived risks.

Quit intention outcomes

Twenty-one of the 35 studies measured the impact of GHW on people’s intention to quit smoking. In four of the studies, quit intentions and perceived risk measures were combined into a cognitive response measure [35, 38, 43, 61] therefore it is not possible to separate the effect of warning format variables on quit intentions from the effect on perceived harm variables for the combined measures. Measures used for intention to quit focused on the “extent to which health warning labels make you more likely to quit smoking” in some studies [5, 41, 46, 59]. In other studies, measures of quit intention focused around planning or intending to quit smoking in the next week, month or year [4, 45, 48, 54].

Eleven studies showed an increase in quit intentions over the course of the study [4, 5, 36, 38, 41, 45, 46, 50, 51, 53, 59]. Gravely, Fong [46] found an increase in thinking about quitting from 21.6% of respondents at pre-policy to 31.3% post-policy in India. Likewise, the implementation of policy in Mauritius [59] resulted in quit intentions increase from 13.5% pre-policy to 26.6% post-policy which was 10–12 months later. In comparison to others, Hall, Sheeran [53] was a short study comprising of a four-week trial, though it had similar findings of an increase in quit intentions over this period. Baseline measures of quit intention among participants in the pictorial warning trial were M = 2.3, SD = 0.9 and at week four, after exposure to pictorial warnings on their cigarette package, quit intentions significantly increased to M = 2.57, SD = 1.07. However, Brewer, Parada [52] followed a comparable study design over a four-week period and found a decrease in quit intentions from baseline (Cohen’s D = 0.26) to week four follow-up (Cohen’s D = 0.16).

Six of the studies identified a decrease in quit intentions after completion of the study [35, 43, 48, 52, 58, 61]. Like perceived risk, a few studies highlighted the immediate impact that new GHW have in increasing quit intentions but an overall decline in the impact months or years later [35, 43, 48, 58]. Hitchman, Driezen [58] and Borland, Wilson [35] both confirmed that for Canada there was a decrease in the impact of its GHW from when they were introduced in 2002 to 2011. Borland, Wilson [35] found that the strength of response for quit intentions (Range from 1 to 3.67) decreased from 1.93 in Wave 1 (2002) to 1.84 in Wave 4 (2006). Similarly, Hitchman, Driezen [58] reported that quit intentions decreased by − 0.504 (OR) over an eight-year period. Durkin, Brennan [48] found a related pattern in Australia. Prior to the introduction of plain packaging 36.10% of smokers intended to quit. During the last stage of the study, quit intentions increased to 42%. However, one-year post implementation of the plain packaging quit intentions decreased back to 35.60%. Taken together, studies identify a positive impact of GHW on intentions to quit that can decline over time. Table 8 presents detailed findings from each relevant study.

Table 8.

Quit intention outcomes

| No. | Author(s), publication year | Group | Quit Intentions | OR or Beta | Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | |||||

| 2 | Borland et al., 2009* | Australia | 1.68 | 2.04 | NA | Cognitive responses combined two questions: “Extent to which the warnings both made the respondent think about the health risks of smoking” and “made them more likely to quit smoking” |

| UK | 1.95 | 1.81 | NA | |||

| Canada | 1.93 | 1.84 | NA | |||

| 3 | Brewer et al., 2016 | NA | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.7 (1.0) | NA | Quit intentions combined three questions: “How likely are you to quit smoking in the next month?”, “How much do you plan to quit smoking in the next month?” and “How interested are you in quitting smoking in the next month?” |

| 4 | Brewer et al., 2019 | NA | 0.26 (0.18, 0.35) | 0.16 (0.07, 0.24 | NA | Quit intentions combines 3 questions: “How interested are you in quitting smoking in the next month?”, “How likely are you to quit smoking in the next month?” and “Are you planning to quit smoking” |

| 6 | Durkin et al., 2015 | Pre PP | NA | NA | 36.10% (OR:1.00) | “Do you intend to quit in the next month?” |

| Late transition | NA | NA | 42% (OR: 1.42) | |||

| Post 1 year PP | NA | NA | 35.60% (OR: 0.98) | |||

| 7 | Elton-Marshall et al., 2015 | NA | 9.0% | 18.0% | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?” |

| 8 | Fathelrahman et al., 2010 | NA | 30 (42.9%) | 28 (40.0%) | NA | “Planning to quit smoking in the future (within the next month, within the next 6 months, sometime in the future beyond six months or not planning to quit)” |

| 9 | Fathelrahman et al., 2013 | NA | 418 (41.1%) | 239 (29.8%) | NA | “any interest in quitting” |

| 11 | Gravely et al., 2016a | NA | 20.6 | 31.3 | OR: 1.76 | “To what extent do the health warnings on cigarette packs make you think about quitting smoking?” |

| 12 | Gravely et al., 2016b | NA | 19.8% (95% CI 14.6; 26.4) | 20.5% (95% CI 15.2; 27.0) | NA | “Are you planning to quit using smokeless tobacco”: Within the next month; Within the next 6 months; Sometime in the future beyond 6 months; Not planning to quit |

| 13 | Green et al., 2014 | NA | 13.50% | 26.60% | OR: 2.69 (95% CI = 1.75–4.15) | “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking” |

| 15 | Hall et al., 2018 | NA | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.57 (1.07) | NA | Quit intentions combined 3 questions: “How much do you plan to quit smoking in the next month?”, “How interested are you in quitting smoking in the next month?” and “How likely are you to quit smoking in the next month?” |

| 16 | Hitchman et al., 2014 | NA | NA | NA | OR: −0.504 (×2 = 6.48) | “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking” |

| 19 | Li et al., 2015 | NA | 2.1 | 1.9 | NA | Cognitive response combined 3 questions: “made them think about the health risks of smoking”, “made them more likely to quit smoking” and “if ‘warning labels on cigarette packages’ motivated them to think about quitting in the past 6 months” |

| 20 | Lin et al., 2016 | Thailand | 0.49 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.06) | NA | Cognitive response combined 2 questions: “made them think about the health risks of smoking” and “made them more likely to quit smoking” |

| Malaysia (wave 2–4) | 0.07 (0.06) | 1.01 (0.06) | NA | |||

| Malaysia (wave 4–6) | 1.01 (0.06) | 0.47 (0.06) | NA | |||

| 23 | McQueen et al., 2015 | NA | 130 (71%) | 133 (73%) | NA | “made them think about quitting” |

| 24 | Nagelhout et al., 2016 | UK | NA | NA | OR: 1.34 | Cognitive responses combined 3 questions: “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels make you think about the health risks of smoking?”, “To what extent, if at all, do the warning labels on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?” and “In the past 6 months, have warning labels on cigarette packages led you to think about quitting?” |

| France | NA | NA | OR: 0.7 | |||

| 26 | Nicholson et al., 2017 | NA | 50 | 54 | NA | “Perceive warning labels effective to quit or stay quit” |

| 27 | Osman et al., 2016 | NA | NA | NA | OR: 1.21 | “Their intention to quit smoking” |

| 28 | Parada et al., 2017* | NA | 2.4 (mean) | 2.6 | NA | Three questions: “How interested are you in quitting smoking in the next month,” “How much do you plan to quit smoking in the next month?” and “How likely are you to quit smoking in the next month?” |

| 31 | Schneider et al., 2012 | NA | NA | NA | 18.59 (6.31) | Motivation to quit was assessed with four items: What extent the warnings induced them to: “consider ceasing their cigarette consumption”, “consider reducing their cigarette consumption”, “think about the health risks associated with smoking” and “refrain from smoking a cigarette at the moment” |

| 34 | Yong et al., 2013 | NA | 27.9 (2.37) | 42.0 (2.19) | NA | “To what extent, if at all, do the health warnings on cigarette packs make you more likely to quit smoking?” |

*Results generated online from web plot digitize

Discussion

GHWs are an important component of the suite of tobacco control policies [63–65]. Literature has identified that a significant wear out becomes present when GHW are left in market over sustained periods [36, 66, 67]. To contribute to the evidence base, this review aimed to systematically identify and synthesize evidence from longitudinal studies which tested different GHW formats and message frames to understand the effects on perceived risk of smoking and benefits of quitting and intentions to quit smoking. Taken together, a total of 35 studies demonstrated that GHWs increase awareness of health risks over time and they have desired outcomes including changing beliefs about smoking, increasing intention to quit and many more. The current review delved deeper into the mechanics of GHWs relationship to perceived health risks and intentions to quit smoking. The contributions of this study are fourfold. Each contribution is detailed in turn.

Firstly, the review identified that pictorial GHWs deliver a superior performance when compared to text only messages both in terms of magnitude and the number of positive outcomes achieved. Pictorial GHWs that are prominent (bigger than 50%) increase perceived health risks and intentions to quit smoking. This review found that GHWs exceeding 50% or more of pack size were most common, and most GHWs were printed on both the front and the back of packs. This review also identified that all studies that increased perceived health risks featured GHWs that exceeded 50% or more of cigarette pack size. The implications are clear that any country that has not mandated that GHWs be 50% of the pack or more should move to do so, given that health risks and intentions to quit smoking can result. Studies have called for more distribution channels of GHWs beyond tobacco packaging [68, 69]. Four studies [3, 33, 47, 57] in this review used package inserts as a complimentary approach to traditional GHWs. Other studies also call for GHWs to be displayed at the point-of-sale [70], via national TV ads [71] and digital channels [68]. Schmidt, Ranney [69] identified that GHWs in public service announcements can improve GHW persuasion.

Secondly, this study illuminates an ongoing reliance on negatively framed messages. Support for the use of positive message framing when targeting illness prevention behaviors including smoking cessation is available [13]. Evidence demonstrates that smokers react to negative messages (fear appeals) harming the quit intention relationship [12]. This review identifies a landscape dominated by negatively framed messages and whilst this approach is effective in increasing understanding of the risks smokers face, other approaches may be needed to induce smokers who are fully aware of health risks to quit smoking. Examination of the wider message framing evidence base indicates that positively framed messages can invoke behavioral change [72, 73]. Accordingly, research examining positive framing is called for to identify messages that can be utilized to increase quit intentions and quitting behavior. This systematic literature review has identified there is no work utilizing a longitudinal research design that has examined the positive benefits of quitting indicating there is a need to extend understanding of the role communication of the benefits of quitting (saving money, having more energy) has on quitting intentions. Further, most of the GHWs are fear-based images with strong visual and direct stimuli and only a few studies have symbolic images. The usage of symbolic images or more subtle cues needs to be studied further to draw conclusive evidence.

Thirdly, this review unveiled that source attribution is not common, although research has indicated credibility strongly contributes to believability [69, 74–76]. Only half of the studies specified credible sources for their warning messages (e.g., Health Canada or US HHS). Perceived risks are a cognitive measure that is heavily influenced by trustworthiness of expertise [77] and perceived authoritativeness [78]. Schmidt, Ranney [69] argued that source credibility needs to be further investigated, either topic-specific, or organization-specific, in order to improve long-term behavioral change in response to tobacco control communications.

Lastly, this review also identified that perceived harms and quit intentions were generally increased by GHWs, and confirmed prior literature [32, 43], noting that wear-out was observed across a range of GHW formats. While understanding the role of GHW formats and message framing must remain a priority, research focused on identifying GHW wear out points is needed to ensure GHW efficacy is optimized. Practically, changing sets of GHWs at the beginning of wear-out is the key to maximize the effectiveness.

Limitations and Future Research