Abstract

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) surrogate neutralization assays that obviate the need for viral culture offer substantial advantages regarding throughput and cost. The cPass SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Kit (GenScript) is the first such commercially available assay that detects antibodies that block receptor-binding domain (RBD)/angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 interaction. We aimed to evaluate cPass to inform its use and assess its added value compared with anti-RBD enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs).

Methods

Serum reference panels comprising 205 specimens were used to compare cPass to plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT) and a pseudotyped lentiviral neutralization (PLV) assay for detection of neutralizing antibodies. We assessed the correlation of cPass with an ELISA detecting anti-RBD immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgM, and IgA antibodies at a single timepoint and across intervals from onset of symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

Compared with PRNT-50, cPass sensitivity ranged from 77% to 100% and specificity was 95% to 100%. Sensitivity was also high compared with the pseudotyped lentiviral neutralization assay (93%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 85–97), but specificity was lower (58%; 95% CI, 48–67). Highest agreement between cPass and ELISA was for anti-RBD IgG (r = 0.823). Against the pseudotyped lentiviral neutralization assay, anti-RBD IgG sensitivity (99%; 95% CI, 94–100) was very similar to that of cPass, but overall specificity was lower (37%; 95% CI, 28–47). Against PRNT-50, results of cPass and anti-RBD IgG were nearly identical.

Conclusions

The added value of cPass compared with an IgG anti-RBD ELISA was modest.

Keywords: COVID-19, ELISA, neutralizing antibodies, SARS-CoV-2, Serology

The results of the current evaluation demonstrate the ability of cPass SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Kit (GenScript) to detect blood specimens with anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. However, the added value of the cPass compared with an IgG anti-RBD ELISA was modest.

Use cases for serological testing for prior exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been reviewed in detail [1, 2]. Despite a rapid increase in the number and availability of serological assays detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, critical knowledge gaps remain regarding the magnitude and kinetics of the correlation between results of these assays and the presence of neutralizing antibodies.

Only a subset of antibodies against a specific antigen can neutralize viral replication. Assays that measure neutralizing antibody levels, such as plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) and microneutralization methods, provide essential data; these assays can help validate candidate diagnostic tests and define serological correlates of immunity. However, functional cell-based assays of SARS-CoV-2 neutralization can only be performed in a Biosafety Level (BSL)-3 laboratory, which is labor-intensive, costly, and limits testing throughput. Pseudotyped viruses have been developed that incorporate the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 and can be cultivated in BSL-2 conditions [3]. Assays incorporating such pseudotyped viruses provide a functional assessment of the host neutralizing antibody responses as an alternative to using the wild-type (WT) virus [4–7]. By contrast, surrogates of neutralization that bypass the need for viral culture would offer substantial advantages in terms of throughput, cost, and scalability. At least 1 direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detecting antibodies to the whole spike protein has received regulatory approval in Europe for assessment of neutralizing antibodies [8]. Furthermore, several groups have proposed blocking assays, leveraging different signal detection methods to quantify the presence of host antibodies that can block the interaction of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with human angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 receptor [9–12].

On November 6, 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for the cPass SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Kit (cPass; GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) [13], which is the first such surrogate neutralization assay to be commercially available. The cPass uses a blocking ELISA format with human ACE-2 receptor molecules coated on an ELISA plate [9, 14]. Human sera preincubated with labeled epitopes of the receptor-binding domain (RBD on S1 proteins) are then transferred to the plate. This blocking ELISA serves as a surrogate assay to inform on the capacity of human sera to block the interaction between the spike fusion protein (through its RBD) and its cellular receptor ACE-2.

The objective of this study was to inform the use of the cPass and assess its added value compared with laboratory-developed anti-RBD ELISA assays by performing an evaluation using a variety of well characterized specimens. Several reference panels were used to better understand the ability of the cPass assay to detect significant titers of neutralizing antibodies assessed by culture-based reference methods. We compared cPass to PRNT and to a pseudotyped virus neutralization assay. We also sought to describe the correlation of cPass with a laboratory-developed indirect ELISA detecting anti-RBD IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies at a single timepoint and across different time frames among specimens collected at a known interval from onset of symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

METHODS

Ethics

All work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in terms of informed consent and approval by an appropriate institutional board. Convalescent plasmas were obtained from donors who consented to participate in this research project at Héma-Québec, the agency responsible for blood supply in Quebec, Canada (Research Ethics Board [REB] no. 2020-004) and the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal ([CR-CHUM] REB no. 19.381). The donors met all donor eligibility criteria: previous confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and complete resolution of symptoms for at least 14 days. At the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), where cPass testing was performed, an REB exemption was granted on the basis that this work was considered to be a laboratory quality improvement project with no risk to participants, and all specimens analyzed were denominalized.

Source of Specimens Tested

We assembled several well characterized SARS-CoV-2 serological specimen panels to assess the performance characteristics of the cPass culture-free neutralization antibody detection kit (Table 1). These panels included the following: a first panel from the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory comprising serological samples from COVID-19 patients, healthy individuals, as well as patients with non-SARS-CoV-2 infections (NML Panel 1) (Supplemental Table 1); NML Panel 2 (the National SARS-CoV2 Serological Panel [NSSP]), comprising 60 serum or plasma specimens from persons with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection documented by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) and 21 specimens from healthy blood donors collected in Canada before July 2019; the World Health Organization (WHO)’s “First WHO International Reference Panel for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin” (NIBSC code 20/268) [15]; and 2 separate curated panels from Héma-Québec and CR-CHUM. The later panels comprised convalescent plasma donors (confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and complete resolution of symptoms for at least 14 days) with either single time point or longitudinal follow-up. In addition to panels using neutralization assays as the reference standard, we assembled 136 specimens from healthy blood donors who tested negative for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by both a laboratory-developed anti-RBD IgG ELISA and a commercial assay detecting anti-nucleocapsid antibodies (Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG Assay). These specimens, collected between May 25 and July 9, 2020, were acquired to help assess the ability of the cPass assay to detect specimens that test negative by other serological methods.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Accuracy of the GenScript cPass Surrogate Viral Neutralization Assay to Detect Neutralizing Antibodies Among Well Characterized Specimen Panels, According to Reference Standard Used

| Source | Number | Reference Standard | Cutoff for Reference Positivitya | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity% (95% CI) | Specificity% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Microbiology Laboratory panel no. 1b (Canada) | 20 (+)/20 (−) | WT PRNT-50 | 1:20 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 100 (82–100) | 95 (76–100) |

| 1:50 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 100 (81–100) | 91 (71–99) | |||

| WT PRNT-90 | 1:20 | 7 | 13 | 0 | 20 | 100 (59–100) | 61 (42–77) | ||

| 1:50 | 5 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 100 (48–100) | 57 (39–74) | |||

| PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 19 | 92 (64–100) | 70 (50–86) | ||

| PLV ID80 | 1:50 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 100 (69–100) | 67 (47–83) | ||

| National Microbiology Laboratory panel no. 2b (Canada) | 60 (+)/21 (−) | WT PRNT-50 | 1:20 | 46 | 0 | 14 | 21 | 77 (64–87) | 100 (84–100) |

| 1:50 | 45 | 1 | 13 | 22 | 78 (65–87) | 96 (78–100) | |||

| PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 24 | 22 | 1 | 34 | 96 (80–100) | 61 (47–74) | ||

| WHO panel (UK)c | 3 (+)/2 (−) | WT PRNT-50 | 1:20 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 100 (16–100) | 67 (9–99) |

| Live Virus (CPE) | 1:20 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 75 (19–99) | 100 (3–100) | ||

| VSV-PV | 1:20 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 (29–100) | 100 (16–100) | ||

| HQ Blood bank -convalescent plasma donors with longitudinal follow-upd | 15 patients, 6 weeks postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 100 (69–100) | 60 (15–95) |

| 14 patients, 10 weeks postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 100 (63–100) | 17 (0–64) | |

| HQ blood bank -convalescent plasma donors with single timepoint follow-upd | 50 patients, any time postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 24 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 86 (67–96) | 45 (24–68) |

| 0–6 weeks postsymptom onset | 11 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 92 (62–100) | 0 (0–46) | |||

| >6 weeks postsymptom onset | 13 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 81 (54–96) | 62 (35–85) | |||

| Overall (vs PLV ID50)e | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 78 | 49 | 6 | 67 | 93 (85–97) | 58 (48–67) |

Abbreviations: anti-S-RBD, antibodies against receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein; CI, confidence interval; CPE, cytopathic effect; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; HQ, Héma-Québec; PRNT, plaque-reduction neutralization test; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; UK, United Kingdom; VSV PV, vesicular stomatitis virus pseudovirus; WHO, World Health Organization; WT, wild type.

aCutoff used to determine cPass positivity was ≥30% inhibition.

b(+) denotes serological specimens positive by severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and (−) denotes serological specimens negative by SARS-CoV-2 PCR but positive for related infections.

c(+) denotes serological specimens positive for SARS-CoV-2 and (−) denotes serological specimens negative for SARS-CoV-2.

dFrom patients meeting public health case definitions of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with either nucleic acid amplification test-confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection or an epidemiological link to a known case of COVID-19 (SARS CoV-2 infection). Specimens characterized by antibodies against receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and PLV ID50.

eResults from the same PLV ID50 neutralization assay were available for all panels except the WHO panel; PLV ID50 assay was used to calculate overall diagnostic accuracy values.

NOTE: WT PRNT-50 or PRNT-90 denotes neutralization titers required for a 50% or 90% plaque reduction, respectively, using SARS-CoV-2 viral culture; PLV ID50 or PLV ID80 denotes the serum dilution to inhibit 50% or 80% of the infection of 293T-ACE2 cells by recombinant viruses bearing the indicated surface glycoproteins.

Culture-Free Neutralization Antibody Detection Assay (cPass)

All specimens and controls were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (including a 10× dilution factor of the primary specimen) and were tested in triplicate. The percentage of inhibition calculation was based on the mean of optical density for each triplicate. A cutoff of 30% inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding was used to determine the presence of neutralizing antibodies, based on the manufacturer’s instructions for use.

Detection of Neutralizing Antibodies by Culture-Based Reference Methods

Neutralizing antibodies were detected via either assessment of plaque reduction neutralization titers using wild-type SARS-CoV-2, or by determining the neutralization half-maximal inhibitory dilution (PLV ID50), or the neutralization 80% inhibitory dilution (PLV ID80) of pseudotyped lentiviral vector [16].

Assessment of plaque-reduction neutralization using wild-type SARS-CoV-2 was performed at the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Reference Laboratory for Microbiology. In brief, heat-inactivated serological specimens were diluted 2-fold from 1:10 to 1:320 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and challenged with an equal volume of 50 plaque-forming units of SARS-CoV-2 (hCoV-19/Canada/ON_ON-VIDO-01-2/2020, EPI_-ISL_425177), which were titrated by plaque assay, for final dilutions of 1:20 to 1:640 [17]. After 1 hour of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, the sera-virus mixtures were added to 12-well plates containing Vero E6 cells at 90% to 100% confluence and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 hour. After adsorption, a liquid overlay comprising 1.5% carboxymethylcellulose diluted in minimal essential medium supplemented with 4% FBS, L-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and sodium bicarbonate was added to each well and plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 72 hours. The liquid overlay was removed, and cells were fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 1 hour at room temperature. The monolayers were stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 10 minutes and washed with 20% ethanol. Plaques were enumerated and compared with controls. The highest serum dilution resulting in 50% and 90% reduction in plaques compared with controls were defined as the PRNT-50 and PRNT-90 endpoint titers, respectively. The PRNT-50 titers and PRNT-90 titers ≥1:20 were considered positive for SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies.

Pseudoviral neutralization testing was performed as previously described [16]. In brief, target cells were infected with single-round luciferase-expressing lentiviral particles. HEK 293T cells were transfected by the calcium phosphate method with the lentiviral vector pNL4.3 R-E- Luc (NIH AIDS Reagent Program) and a plasmid encoding for SARS-CoV-2 spike at a ratio of 5:4. Experiments were calibrated using a Luc signal of approximately 1 million relative luciferase units (RLU). Two days posttransfection, cell supernatants were harvested and stored at –80°C until use. 293T-ACE2 target cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well luminometer-compatible tissue culture plates (PerkinElmer) 24 hours before infection. Recombinant viruses in a final volume of 100 µL were incubated in dilutions of heat-inactivated sera of 1:50, 1:250, 1:1250, 1:6250, and 1:31250 (we have observed nonspecific neutralization of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) pseudotyped virions occurring at concentrations of serum <1:50) for 1 hour at 37°C and were then added to the target cells followed by incubation for 48 hours at 37°C; cells were lysed by the addition of 30 µL passive lysis buffer (Promega) followed by 1 freeze-thaw cycle. An LB942 TriStar luminometer (Berthold Technologies) was used to measure the luciferase activity of each well after the addition of 100 µL luciferin buffer (15 mM MgSO4, 15 mM KPO4 [pH 7.8], 1 mM ATP, and 1 mM dithiothreitol) and 50 µL of 1 mM d-luciferin potassium salt (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The neutralization half-maximal inhibitory dilution (ID50) or the neutralization 80% inhibitory dilution (ID80) represents the sera dilution to inhibit 50% or 80% of the infection of 293T-ACE2 cells by recombinant viruses bearing the indicated surface glycoproteins.

Indirect Anti-Receptor-Binding Domain Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays

Specimens were analyzed with a laboratory-developed indirect ELISA detecting anti-RBD IgG, IgM, and IgA as previously described [16, 18]. Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S RBD proteins (or OC43 S RBD proteins) (2.5 mg/mL), or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (2.5 mg/mL) as a negative control, were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline and were adsorbed to plates (MaxiSorp; Nunc) overnight at 4°C. Coated wells were blocked with blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20, 2% BSA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Wells were washed 4 times with washing buffer (Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% Tween 20). CR3022 monoclonal antibody ([mAb] 50 ng/ mL) or sera from SARS-CoV-2-infected or uninfected donors (1/100; 1/250; 1/500; 1/1000; 1/2000; 1/4000) were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated with the RBD-coated wells for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were washed 4 times with washing buffer followed by incubation with secondary Abs (diluted in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by 4 washes. Horseradish peroxidase enzyme activity was determined after the addition of a 1:1 mix of Western Lightning oxidizing and luminol reagents (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Light emission was measured with a LB942 TriStar luminometer (Berthold Technologies). Signal obtained with BSA was subtracted for each serum and were then normalized to the signal obtained with CR3022 mAb present in each plate. Alternatively, the signal obtained with each serum on OC43 RBD was normalized with the signal obtained with 4.3E4 mAb present in each plate. The seropositivity threshold was established using the following formula: mean RLU of all COVID-19-negative sera normalized to CR3022 (or 4.3E4) + (3 standard deviations of the mean of all COVID-19 negative sera).

Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG Assay

The Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG assay (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, United States) detecting anti-nucleocapsid IgG was performed on the Architect i2000sr platform according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specimens were thawed on the day of testing and were centrifuged 10 000 ×g for 10 minutes before each run.

Statistical Analysis

The diagnostic accuracy of the cPass surrogate viral neutralization assay was estimated compared with different reference standards (WT PRNT-50; WT PRNT-90; PLV ID50; PLV ID80, live virus [cytopathic effect], and VSV-pseudovirus). Sensitivities and specificities are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The effect of varying the cutoff value (ie, %inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding) for cPass positivity on the diagnostic accuracy of the cPass against a PLV ID50 reference standard was investigated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The association between cPass %inhibition and results obtained using laboratory-developed ELISA detecting anti-S-RBD IgG, IgM, and IgA, or against PLV ID50 are presented in scatterplots with the strength of these associations informed by Pearson correlation. Finally, among specimens from individuals with a known interval from onset of SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms and repeated testing over time, spaghetti plots were created to investigate any change in signal over time for the cPass and direct anti-S-RBD ELISA with statistical significance assessed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test (P < .05 denoted by *). Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.2 (R Core Team; Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Diagnostic Accuracy for the Detection of Anti-Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus 2 Neutralizing Antibodies, and the Impact of Using Different Reference Standards

Table 1 shows the estimated diagnostic accuracy of the GenScript cPass neutralization antibody detection assay among well characterized specimen panels, according to different reference standards. Among various reference standards, results from the same PLV ID50 assay were available for all panels except the WHO panel, and this was used to estimate aggregate diagnostic accuracy values across several panels.

Overall, cPass had sensitivity ranging from 77% to 100% and specificity of 95% to 100% compared with the reference standard of a 50% plaque reduction neutralization using SARS-CoV-2 viral culture (WT PRNT-50) (Table 1). Changing the WT PRNT-50 cutoff titer from 1:20 to 1:50 had minimal impact on specimen categorization. Sensitivity remained very high compared with the reference standard of a neutralization half-maximal inhibitory dilution using a validated pseudotyped lentiviral vector neutralization assay (PLV ID50) with a cutoff titer of 1:50, but specificity was lower than that compared with WT PRNT-50, ranging from 17% to 70% (Table 1).

The effect of cutoff values on the diagnostic accuracy of the GenScript cPass assay is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve using the reference standard of PLV ID50 yielded an area under the ROC curve of 0.858.

Effect of Serial Dilution on the Accuracy for Detecting Sera With Positive Plaque-Reduction Neutralization Test-90 Titers

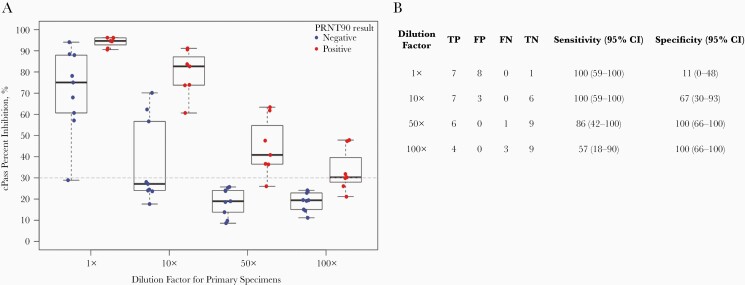

Against the most stringent reference standard of 90% plaque reduction neutralization using SARS-CoV-2 viral culture (WT PRNT-90), estimated specificity was reduced compared with WT PRNT-50. Specificity remained similar whether a cutoff WT PRNT-90 titer for positivity of 1:20 or 1:50 was used (61% [95% CI, 42–77] and 57% [95% CI, 39–74], respectively) (Table 1). We performed serial dilution of the 16 primary specimens from the National Microbiology Laboratory Panel with WT PRNT-50 titers ≥1:20 to determine whether we could establish a dilution that increased specificity for detecting those with WT PRNT-90 titers ≥1:20 without sacrificing sensitivity (Figure 1). A 50-fold dilution of specimens with positive WT PRNT-50 titers increased specificity for those with positive WT PRNT-90 titers from 11% (95% CI, 0–48) to 100% (95% CI, 66–100), with 1 missed PRNT-90-positive specimen.

Figure 1.

Effect of serial dilution on the accuracy for detecting sera with positive plaque-reduction neutralization test (PRNT)-90 titers. Serial dilution of 16 of the primary specimens with wild-type (WT) PRNT-50 titers ≥1:20 was performed to establish a dilution that increased specificity for detecting those with WT PRNT-90 titers ≥1:20. Three of the 19 specimens with WT PRNT-50 titers ≥1:20—all [PRNT-50 1:20 (+)/PRNT-90 1:20 (−)]—were not available in sufficient quantity to perform serial dilution testing. (A) shows individual data points according to dilution and WT PRNT-90 status (positive ≥1:20). Box plots depict the median and interquartile range. The horizontal dashed line depicts the manufacturer’s recommended cutoff for cPass positivity. (B) details results and estimates of sensitivity and specificity for serial dilution factor. All dilution factors are additional to the 10× dilution required in the manufacturer’s instructions. WT PRNT-90 denotes neutralization titers required for a 90% plaque reduction using severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 viral culture. FP, false positive; FN, false negative; TN, true negative; TP true positive.

Agreement of the GenScript cPass Assay With Laboratory-Developed Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Detecting Anti-Receptor-Binding Domain Immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgM, and IgA

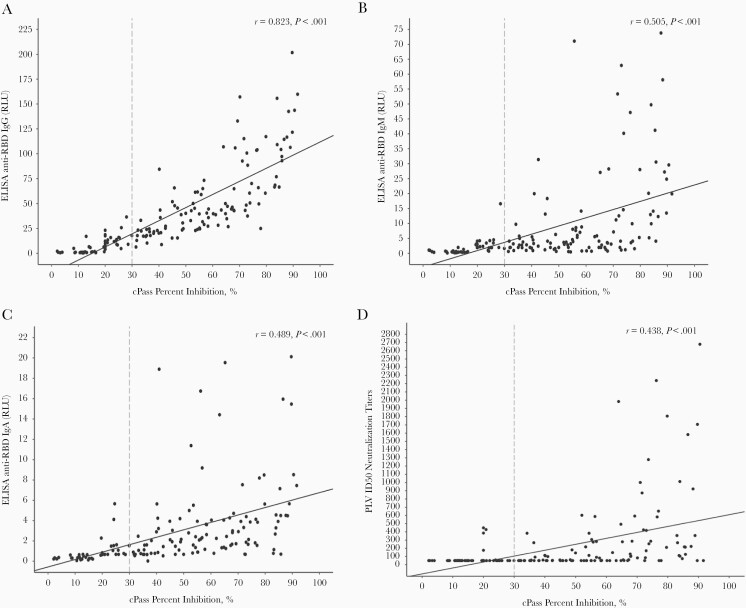

Results obtained with cPass were compared with those obtained using laboratory-developed ELISA detecting anti-RBD IgG, IgM, and IgA and to those of PLV ID50 (Figure 2). Highest agreement between cPass percentage inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding and ELISA readout was seen for anti-RBD IgG (Pearson correlation coefficitient r = 0.823), compared with that observed with anti-RBD IgM, IgA, and PLV ID50 (r = 0.505, 0.489, and 0.438, respectively). The diagnostic accuracy of categorical anti-RBD IgG results for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies was very similar to that observed with the cPass for most panels and reference standards (Tables 1 and 2). Compared with PLV ID50, cPass overall sensitivity was 93% (95% CI, 85–97) and specificity 58% (95% CI, 48–67), whereas anti-RBD IgG overall sensitivity was 99% (95% CI, 94–100) and specificity 37% (95% CI, 28–47).

Figure 2.

Correlation of the GenScript cPass assay with antibodies against receptor binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (anti-S-RBD) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and PLV ID50. Correlation of the GenScript cPass assay with the anti-S-RBD ELISA normalized relative luciferase units (RLU) for each plasma tested at a dilution (1:500) is presented. Scatterplots and Pearson correlation coefficient for results obtained with cPass compared with those obtained using laboratory-developed ELISA detecting anti-RBD immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgM, IgA and to the reciprocal titer of PLV ID50 (A, B, C, and D, respectively). The vertical dashed line depicts the manufacturer’s recommended cutoff for cPass positivity. Cutoffs for anti-S-RBD ELISA positivity were as follows:; 4.335 for IgG, 2.983 for IgM, and 1.084 for IgA. Cutoff for the reciprocal titer of PLV ID50 was 50. Specimens from the NML panel 2 and Héma-Québec convalescent plasma donors panel are included in the above figure. Specimens from the NML panel no. 1 were excluded because anti-S-RBD ELISA for IgM and IgA were not performed.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Accuracy of a Laboratory-Developed IgG Anti-RBD ELISA to Detect Neutralizing Antibodies

| Source | Number | Reference Standard | Cutoff for Positivitya | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Microbiology Laboratory panel no. 1b (Canada) | 20 (+)/20 (−) | WT PRNT-50 | 1:20 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 100 (82–100) | 95 (76–100) |

| 1:50 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 100 (81–100) | 91 (71–99) | |||

| WT PRNT-90 | 1:20 | 7 | 13 | 0 | 20 | 100 (59–100) | 61 (42–77) | ||

| 1:50 | 5 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 100 (48–100) | 57 (39–74) | |||

| PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 19 | 92 (64–100) | 70 (50–86) | ||

| PLV ID80 | 1:50 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 100 (69–100) | 67 (47–83) | ||

| National Microbiology Laboratory panel no. 2b (Canada) | 60 (+)/21 (−) | WT PRNT-50 | 1:20 | 59 | 0 | 1 | 21 | 98 (91–100) | 100 (84–100) |

| 1:50 | 57 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 98 (91–100) | 91 (72–99) | |||

| PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 25 | 34 | 0 | 22 | 100 (86–100) | 39 (26–53) | ||

| HQ blood bank -convalescent plasma donors with longitudinal follow-upc | 15 patients, 6 weeks postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 100 (69–100) | 40 (5–85) |

| 14 patients, 10 weeks postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 100 (63–100) | 0 (0–46) | |

| HQ blood bank -convalescent plasma donors with single time point follow-upc | 50 patients, any time postsymptom onset | PLV ID50 | 1:50 | 28 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 100 (88–100) | 0 (0–15) |

| 0–6 weeks postsymptom onset | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 100 (74–100) | 0 (0–46) | |||

| >6 weeks postsymptom onset | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 100 (79–100) | 0 (0–21) | |||

| Overall (vs PLV ID50) | 1:50 | 83 | 73 | 1 | 43 | 99 (94–100) | 37 (28–47) |

Abbreviations: anti-S-RBD, antibodies against receptor binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; HQ, Héma-Québec; PRNT, plaque-reduction neutralization test; TN, true negative; TP, true positive; WT, wild type.

aCutoff used to determine immunoglobulin (Ig)G anti-RBD ELISA positivity was ≥4.335.

b(+) denotes serological specimens positive by SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and (−) denotes serological specimens negative by SARS-CoV-2 PCR but positive for related infections.

cFrom patients meeting public health case definitions of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with either nucleic acid amplification test-confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection or an epidemiological link to a known case of COVID-19 (SARS CoV-2 infection). Specimens characterized by anti-S-RBD ELISA and PLV ID50.

NOTE: WT PRNT-50 or PRNT-90 denotes neutralization titers required for a 50% or 90% plaque reduction, respectively, using SARS-CoV-2 viral culture; PLV ID50 or PLV ID80 denotes the serum dilution to inhibit 50% or 80% of the infection of 293T-ACE2 cells by recombinant viruses bearing the indicated surface glycoproteins.

However, when NML Panel 2 was considered in isolation, categorical results for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies differed substantially between cPass and anti-RBD IgG in terms of sensitivity compared with WT PRNT-50 (cPass 77% [95% CI, 64–87], anti-RBD IgG 98% [95% CI, 91–100]) and specificity compared with PLV ID50 (cPass 61% [95% CI, 47–74], anti-RBD IgG 39% [95% CI, 26–53]). If a cutoff of 20% RBD-ACE2 binding inhibition were used instead of the 30% cutoff recommended by the manufacturer, cPass sensitivity against WT PRNT-50 would rise to 92% (95% CI, 82–97) with a lower estimated specificity of 46% (95% CI, 33–60).

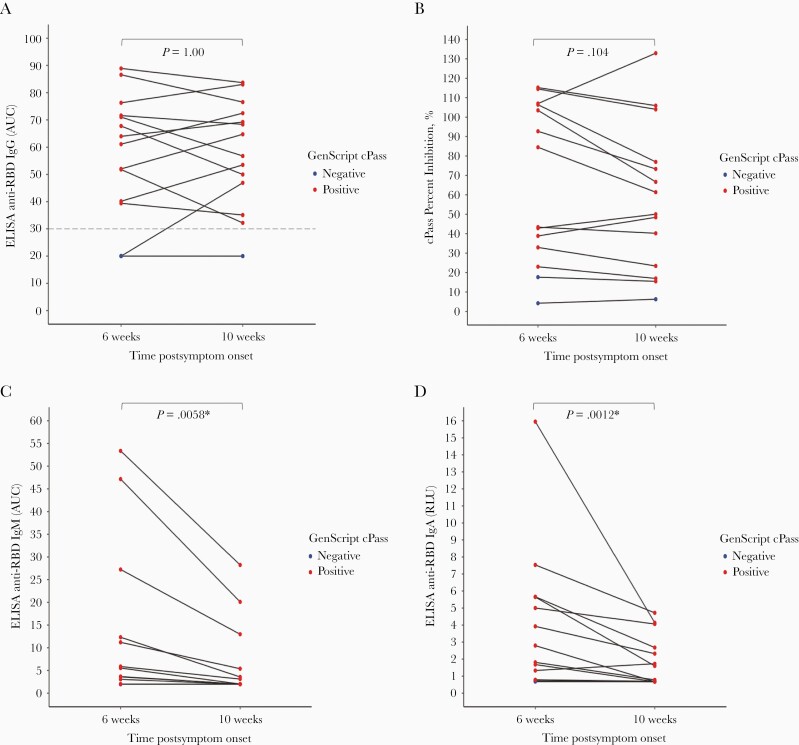

Among paired specimens from the same individual collected at a known interval from SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, aggregate results of both cPass and direct anti-RBD IgG ELISA did not change between 6 weeks and 10 weeks after diagnosis (P = 1.00 and .104, respectively, by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test) (Figure 3). In contrast, ELISA readouts decreased significantly over the same time frame for direct anti-RBD IgM (P = .0058) and IgA (P = .0012).

Figure 3.

Change of signal over time for GenScript cPass and antibodies against receptor binding domain of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 ([SARS-CoV-2] anti-RBD) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Spaghetti plot of results obtained with cPass (A), and the plots shown in B, C, and D represent (B and C) the areas under the curve (AUC) calculated from relative luciferase units (RLU) obtained with serial plasma dilutions or (D) the normalized RLU for 1 plasma dilution (1:500) for laboratory-developed ELISA detecting anti-RBD immunoglobulin (Ig)G, IgM, and IgA (B, C, D, respectively) among specimens collected at a known interval from SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Horizontal lines indicate paired specimens form the same individual. P values are calculated via the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and values <.05 are designated with an asterisk. In all panels, red dots denote specimens with positive cPass results, and blue dots denote specimens with negative cPass results. cPass positivity based on a cutoff of ≥30% inhibition. Cutoffs for anti-S-RBD ELISA positivity were as follows: 4.335 for IgG, 2.983 for IgM, and 1.084 for IgA.

Negative Agreement Between cPass and Other Serological Assays

Among 136 specimens from healthy blood donors who tested negative for the presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by both a laboratory-developed anti-RBD IgG ELISA and the Abbott Architect SARS-CoV-2 IgG Assay (anti-N protein), cPass yielded negative results for 134 specimens (negative agreement 98.5%; 95% CI, 94.8–99.8).

DISCUSSION

Rapid and high-throughput surrogates for PRNT or pseudovirus neutralization assays that bypass the need for cell culture are awaited with the belief that they will offer additional information to that from standard direct immunoassays, such as a higher specificity for neutralizing antibodies. The cPass SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Kit (cPass) is the first such assay to be commercially available and to receive FDA EUA in the United States. An evaluation of a cPass prototype, using a cutoff value of 20% inhibition, found that it could provide a high-throughput screening tool for confirmatory PRNT testing [19]. The results of the current evaluation support the ability for cPass to detect neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, although specificity varied considerably depending on the reference assay used. Our data also extend these findings by showing that cPass performed similarly to a nonblocking anti-RBD ELISA among varied well characterized specimen panels.

Among 205 specimens evaluated by a SARS-CoV-2 reference neutralization assay in the current work—either WT PRNT-50 or PLV ID50—the overall estimated sensitivity of cPass for detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies was high, regardless of the reference standard technique or reference standard cutoff titer for positivity. The lower sensitivity of cPass compared with WT PRNT-50 observed for specimens in NML Panel 2 (Table 1) appears related to the choice of 30% RBD-ACE2 binding inhibition cutoff recommended by the manufacturer, which may result in false-negative results for specimens with low titers of neutralizing antibodies. Among all specimens evaluated, however, reducing the inhibition cutoff to 20% would have a minimal impact on overall sensitivity and yield substantial reduction in overall specificity compared with PLV ID50 (Supplemental Figure 1). Our results do not suggest that the cPass assay, targeting only RBD-ACE2 blockade, would miss a substantial proportion of patients with neutralizing antibodies that target non-RBD epitopes [20–22]. This may be because neutralizing antibodies to non-RBD epitopes usually occur concomitantly with anti-RDB neutralizing antibodies, instead of in isolation.

By contrast, estimates of the specificity of cPass for the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies were contingent of the reference standard used (Table 1). There was near-perfect negative agreement with WT PRNT-50 using a cutoff titer of either 1:20 or 1:50. However, negative agreement was much lower when cPass was compared with either PLV ID50 or WT PRNT-90. Our data raise the unresolved questions of which reference technique (ie, wild-type or pseudotyped live viral culture), level of stringency (eg, 50% inhibition of infection vs 80%, 90%, etc), and cutoff titer (eg, 1:20 vs 1:50) best represent serocorrelates of protection to SARS-CoV-2, or other relevant applications. Moreover, protocols can vary widely for the same technique across different laboratories, requiring caution in the interpretation of these and other data [23]. In the current manuscript, PLV ID50 with a cutoff titer of 1:50 was used as the overall comparator because it was the technique applied to all available specimen panels except the 5-member panel from WHO. Our results must be interpreted in context with this potential source of bias. However, we note that this technique has been used by other groups and thus offers a high degree of generalizability with other results [24, 25].

The cPass assay detected all specimens with positive WT PRNT-90 titers, with a significant proportion of false positives (Figure 1). A 50-fold dilution of the 16 primary specimens with WT PRNT-50 titers ≥1:20 increased specificity for detecting those with WT PRNT-90 titers ≥1:20 from 11% (95% CI, 0–48) to 100% (95% CI, 66–100). This may represent a useful approach for using the cPass assay to identify blood specimens with positive WT PRNT-90 titers, which has been proposed as a desirable characteristic for sera used in convalescent plasma trials by some regulatory agencies.

Finally, results of the cPass assay are best correlated with those of a laboratory-developed indirect anti-RBD ELISA detecting IgG, both at a single time point (Table 2, Figure 2) and across time among paired specimens from the same individual collected at a known interval from symptoms onset (Figure 3). However, a slightly higher specificity for the detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies was observed for cPass compared with anti-RBD IgG ELISA across most panels (Tables 1 and 2). The fact that results of cPass and anti-RBD IgG remained stable between 6 and 10 weeks postsymptom onset, while ELISA readouts decreased significantly over the same time frame for anti-RBD IgM and IgA, is potentially concerning given recent work suggesting a major role of IgM and IgA in the neutralizing activity of convalescent plasma against SARS-CoV-2 [18, 26–28]. The observed trend toward lower specificity of cPass at later time points among convalescent plasma donors with longitudinal follow-up (ie, 60% [95% CI, 15–95] at 6 weeks vs 17% [95% CI, 0–64] at 10 weeks) may thus be related to loss of neutralizing IgM (Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that a positive cPass result in the context of a remote infection may not accurately predict the presence of neutralizing antibodies. In addition, specificity of the cPass may be affected by the possibility that part of the inhibition of binding in the cPass assay could be due to steric hindrance by the abundant antispike antibodies of the IgG isotype rather than by true neutralization (as occurs in vivo).

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the current evaluation demonstrate the ability of cPass to detect blood specimens with anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. However, the added value of cPass compared with an IgG anti-RBD ELISA was modest.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the convalescent plasma donors who participated in this study; the Héma-Québec team involved in convalescent donor recruitment and plasma collection; the staff members of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CR-CHUM) Biosafety Level 3 Platform for technical assistance; and Stefan Pöhlmann (Georg-August University, Göttingen, Germany) for the plasmid coding for SARS-CoV-2 S.

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support. C. P. Y. and J. Pa. hold a “Chercheur-boursier clinicien” career award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé. This work was partially funded by le Ministère de l’Économie et de l’Innovation du Québec (Program de soutien aux organismes de recherche et d’innovation), the Fondation du CHUM, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (via the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force) (to A. F.). A. F. is the recipient of a Canada Research Chair on Retroviral Entry (RCHS0235 950-232424). G. B.-B., and J. Pr. are supported by CIHR fellowships. R. G. is supported by a MITACS Accélération postdoctoral fellowship. cPass kits were provided in kind by GenScript.

Potential conflicts of interest. J. Pa. reports grants from MedImmune, grants from Sanofi Pasteur, grants and personal fees from Seegene, and grants and personal fees from AbbVie, outside the submitted work. M. P. C. reports personal fees from GEn1E Lifesciences (as a member of the scientific advisory board) and personal fees from nplex biosciences (as a member of the scientific advisory board), both outside the submitted work. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Cheng MP, Yansouni CP, Basta NE, et al. Serodiagnostics for severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173:450–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Caeseele P, Bailey D, Forgie SE, et al. ; Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network; Canadian Society of Clinical Chemists; Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada; Canadian Association for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; COVID-19 Immunity Task Force. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) serology: implications for clinical practice, laboratory medicine and public health. CMAJ 2020; 192:E973–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crawford KHD, Eguia R, Dingens AS, et al.. Protocol and reagents for pseudotyping lentiviral particles with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for neutralization assays. Viruses 2020; 12:513–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nie J, Li Q, Wu J, et al. Establishment and validation of a pseudovirus neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9: 680–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amanat F, Stadlbauer D, Strohmeier S, et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat Med 2020; 26:1033–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li Q, Liu Q, Huang W, Li X, Wang Y. Current status on the development of pseudoviruses for enveloped viruses. Rev Med Virol 2018; 28:e1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hyseni I, Molesti E, Benincasa L, et al. Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 lentiviral pseudotypes and correlation between pseudotype-based neutralisation assays and live virus-based micro neutralisation assays. Viruses 2020; 12:1011–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DiaSorin S.p.A. Liaison(R) SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG brochure -A quantitative assay with correlation to neutralizaing antibodies. 2020; 6. https://www.diasorin.com/sites/default/files/allegati_prodotti/liaisonr_sars-cov-2_s1s2_igg_m0870004366-d_lr.pdf

- 9. Tan CW, Chia WN, Qin X, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike protein-protein interaction. Nat Biotechnol 2020; 38:1073–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muruato AE, Fontes-Garfias CR, Ren P, et al. A high-throughput neutralizing antibody assay for COVID-19 diagnosis and vaccine evaluation. Nat Commun 2020; 11:4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danh K, Karp DG, Robinson PV, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies with a cell-free PCR assay [preprint ]. medRxiv 2020; 2020.05.28.20105692. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abe KT, Li Z, Samson R, et al. A simple protein-based surrogate neutralization assay for SARS-CoV-2. JCI Insight 2020; 5:e142362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes first test that detects neutralizing antibodies from recent or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. FDA News Release, Published November 6, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-first-test-detects-neutralizing-antibodies-recent-or. Accessed 20 January 2021. 2020.

- 14. GenScript USA Inc. cPass(TM) SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Kit -Instructions for use. 2020; 18. https://www.fda.gov/media/143583/download. Accessed 14 December 2020.

- 15. The National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC). First WHO International Reference Panel for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin (NIBSC code: 20/268). 2020; 2. https://www.nibsc.org/documents/ifu/20-268.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2021.

- 16. Prévost J, Gasser R, Beaudoin-Bussières G, et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 spike. Cell Rep Med 2020; 1: 100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendoza EJ, Manguiat K, Wood H, Drebot M. Two detailed plaque assay protocols for the quantification of infectious SARS-CoV-2. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2020; 57:ecpmc105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beaudoin-Bussières G, Laumaea A, Anand SP, et al. Decline of humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 spike in convalescent individuals. mBio 2020; 11:e02590-02520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valcourt EJ, Manguiat K, Robinson A, et al. Evaluation of a commercially-available surrogate virus neutralization test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021; 99:115294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Voss WN, Hou YJ, Johnson NV, et al. Prevalent, protective, and convergent IgG recognition of SARS-CoV-2 non-RBD spike epitopes in COVID-19 convalescent plasma. Science 2021; eabg5268. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wec AZ, Wrapp D, Herbert AS, et al. Broad neutralization of SARS-related viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. Science 2020; 369:731–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu L, Wang P, Nair MS, et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against multiple epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 spike. Nature 2020; 584:450–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferrara F, Temperton N. Pseudotype neutralization assays: from laboratory bench to data analysis. Methods Protoc 2018; 1:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muecksch F, Wise H, Batchelor B, et al. Longitudinal serological analysis and neutralizing antibody levels in coronavirus disease 2019 convalescent patients. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:389–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gaebler C, Wang Z, Lorenzi JCC, et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021; 591:639–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gasser R, Cloutier M, Prévost J, et al. Major role of IgM in the neutralizing activity of convalescent plasma against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep 2021; 34: 108790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klingler J, Weiss S, Itri V, et al. Role of IgM and IgA antibodies in the neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:957–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sterlin D, Mathian A, Miyara M, et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci Transl Med 2021; . 13:eabd2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.