Abstract

Objective

Serious mental illness is associated with physical health comorbidities, however most research has focused on adults. We aimed to synthesise existing literature on clinical and behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors of young people on mental health inpatient units.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted, using electronic searches of PsycINFO, EMBASE, AMED, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Ovid MEDLINE. Eligible studies included child/adolescent mental health inpatient units for <25 years, reporting clinical/behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors. Studies containing adult samples, case-studies, or eating disorder populations were excluded. The main clinical outcome was weight, and main behavioral outcome was tobacco use.

Results

Thirty-nine studies were identified (n = 809,185). Pooled prevalence rates of young people who were overweight (BMI > 25) was 32.4% (95% CI 26.1%–39.5%; n = 2789), and who were obese (BMI > 30) was 15.5% (95% CI 4.5%–41.6%; n = 2612). Pooled prevalence rates for tobacco use was 51.5% (95% CI 32.2–70.2; N = 804,018). Early signs of metabolic risk were observed; elevated blood cholesterol, presence of physical health conditions, and behavioral risk factors (e.g. physical inactivity).

Conclusions

This review highlights the vulnerability of young people admitted to inpatient units and emphasises the opportunity to efficiently monitor, treat and intervene to target physical and mental health.

Keywords: Metabolic health, Inpatient psychiatry, Youth mental health, Child and adolescent psychiatry, Physical health risk

1. Introduction

People with serious mental illness (SMI) experience poor physical health, resulting in a 15–20 year mortality gap [[1], [2], [3]]. They are more likely to develop cardiovascular disease and obesity, display frequent behavioral and lifestyle risk factors, receive substandard physical health care, and experience cardiometabolic side effects of medication [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Improving the physical health of people with SMI is an international priority, as the extent of these health inequalities has been labelled a human rights scandal. This recognition has resulted in various international health bodies producing guidelines on addressing physical health in people with SMI, including the World Health Organisation [5], the World Psychiatric Association [6], a Lancet Commission [7], along with national guidance from Public Health England [8].

Currently, much of the attention in this area focuses on the physical health of adults with SMI, as adulthood is when cardiovascular morbidity and mortality become most apparent. However, there is evidence that cardiometabolic risk (the likelihood of developing conditions such as cardiovascular disease) is present at an early stage, thus affording the opportunity to intervene to prevent comorbid conditions [[9], [10], [11]]. Research suggests people experiencing a first episode of psychosis have poor physical health [12], and even antipsychotic naive individuals who are at-risk for SMI display evidence of metabolic ill-health [[9], [10], [11]]. Additionally, adolescents requiring mental health care for a range of transdiagnostic conditions are more likely to experience additional barriers to living a healthy lifestyle, such as low motivation, and social withdrawal [10,13,14]. It is important to address this at an early stage, as physical health problems which occur during childhood, and early adolescence are often persistent, and as recognised by the World Health Organisation can have a detrimental effect on long-term physical and mental health development [15].

Young people who receive care from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) are a vulnerable group in relation to physical health, particularly those on inpatient units. As well as the associated poor physical health of SMI, this has been linked to the ‘obesogenic nature’ of the inpatient environment [16,17]. Increased restrictions on movement, lack of access to outdoor space and community facilities, reduced opportunities to be active, less control over dietary intake, and increased access to calorie dense foods, all impede a young person's ability to live a healthy lifestyle. Indeed, previous research has found physical health problems are common on adolescent inpatient units, but often go undetected and untreated [18]. Our recent service evaluation also found evidence of poor physical health upon admission to CAMHS inpatient units, including high levels of obesity which increased suddenly over time, metabolic dysfunction and behavioral risk [19]. However, to date there has been no synthesis of the literature on physical health or cardiometabolic risk of adolescent inpatients receiving mental health care.

2. Aims

This study aims to synthesise the existing literature on cardiometabolic risk, both clinical and behavioral of young people in these settings. The review questions were:

-

1.

What is the clinical cardiometabolic risk in young people on mental health inpatient units?

-

2.

What behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors are present in young people on mental health inpatient units?

3. Method

This review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting systematic reviews [20]. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO, (CRD: CRD42019161295, 2019).

3.1. Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were original research articles published in peer-reviewed English-language journals. Eligible populations were from specialised child, adolescent and young people's inpatient services. This included any inpatient mental health service for people up to 25 years. All psychological disorders and diagnoses were eligible, with the exception of specialist eating disorder inpatient services. The upper age limit was decided according to literature highlighting the growing evidence recommending young people's mental health services (both inpatient and outpatient services) should extend to 25 years, in line with definitions of adolescence based on young people's cognitive development [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. It also allowed inclusion of specialist international services which extend up to 25 years. Studies reporting clinical or behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors within this population were eligible. Clinical assessments included weight, height, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP); carbohydrate metabolism-related biomarkers including markers of diabetes risk (glucose, HbA1c), central adiposity (waist circumference), and common lipid outcomes associated with cardiometabolic risk (cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides (TG)). Behavioral risk factors included tobacco, alcohol, physical activity and diet. Observational studies (including prospective, retrospective, cross-sectional, case-control, cohort) and intervention studies (which report physical health at baseline) were eligible.

Studies including older populations, mixed samples including individuals under 25 whose data could not be separated from the whole sample, and studies which did not report physical health or cardiometabolic risk were excluded. Case studies, conference abstracts, reviews and non-English language papers were also excluded. Although all mental health diagnoses were eligible, studies which reported populations from specialist intensive eating disorder services were excluded due to the significant physical health implications associated with these disorders. Data from intervention studies targeting smoking cessation or alcohol dependence in psychiatric populations were also excluded, as the whole sample would not have been representative of a broader inpatient group.

3.2. Search strategy

An electronic database search was conducted on 10th January 2020 using PsycINFO, EMBASE, AMED, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Ovid MEDLINE. Search terms associated with ‘inpatient settings’, ‘mental health’, ‘children/adolescents’ and ‘physical health’ were used (search strategy available). A search of Google Scholar was also conducted and reference lists of eligible papers were scanned to identify additional papers. Search strategy was intentionally broad to cover all publications from database conception until the search date.

3.3. Study selection/data extraction

Four reviewers independently screened articles for eligibility, two independent reviewers checked each paper for inclusion at both title/abstract and full text, using the online platform Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Two reviewers extracted data using a Microsoft Excel tool designed to record: (a) study characteristics (author, publication year, country, study design); (b) sample characteristics (sample size, gender, age); (c) clinical demographics (diagnoses, description of service, medication, length of stay); (d) physical health measures (measure, sample mean/prevalence); (e) behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors (measure, sample mean/prevalence), and (f) summary of findings. Accuracy of the data was checked by independent members of the study team. Data extracted was grouped into specific risk factors, and narrative synthesis was conducted.

3.4. Quality assessment

Quality and risk of bias was assessed by two independent reviewers using a modified version of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale for assessing quality of non-randomised studies [25] (Supplementary data).

3.5. Meta-analysis

Meta-analyses were used to determine the prevalence and weighted averages for cardiometabolic risk factors containing three or more samples using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3. Proportionate random-effects meta-analyses were conducted on the data to calculate pooled estimates (such as smoking rates). Measures of central tendency were calculated for comparable quantifiable date with 95% CI. Variance was estimated using Cochran's Q and indexed using I2 (which estimates the extent of variance caused by between-study heterogeneity rather than chance). DerSimonian and Laird [26], random-effects models were used throughout to account for heterogeneity between studies.

4. Results

4.1. Search results

Study selection and exclusion is summarised in Fig. 1. Database searches retrieved 1721 unique citations after the removal of duplicates, of which 1553 were excluded at title-abstract stage, and a further 130 after full text review (Fig. 1). One additional paper was identified through reference lists. Thirty-nine unique studies were included (Table 1). Studies were conducted in 11 countries across North America (n = 19), Europe (n = 10), Asia (n = 5), Australia (n = 4), Africa (n = 1). Study characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Almost all studies were cross-sectional studies, and only two included a healthy control group. Quality assessments found the risk of bias was high (n = 19), medium (n = 16), and low (n = 4) (Supplementary Data). Thirty-nine studies were included in the synthesis and 36 were included in at least one of the meta-analyses below.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Table 1.

Details of included studies.

| Study (+ Country) | Patient Characteristics | Sample Size | Mean Age | Gender | Setting | Average Length of Stay | Diagnoses | Medication | Study Type | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Haidar et al., (2003) [27] Saudi Arabia |

Children and adolescents with a range of psychiatric diagnoses receiving treatment from an inpatient hospital. | 109 | Not reported. | Not reported | Child and adolescent consultation-liaison psychiatric team for under 18 s. | Not reported | 29% (n = 32) no psychiatric illness, 24% (n = 26) MDD, 10% (n = 11) adjustment disorder, 6.5% (n = 7) deliberate self harm, 5.5% (n = 6) acute organic brain syndrome, 3% (n = 3) conversion disorder, 3% (n = 3) ADHD, 19% (n = 21) other not described | 56% (n = 61) none, 24% (n = 26) antidepressant, 10% (n = 11) anticonvulsant, 8% (n = 9) antipsychotic, 2% (n = 2) CNS stimulant | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | Prevalence of physical health condition (diabetes) | 6.5% young people had comorbid diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. |

| Barzman et al., (2013) [28] USA |

Young boys hospitalized with a range of psychiatric conditions classified as at high or low risk of aggression, between the ages of 7–9. | 17 | No Aggression = 8.4 (sd 0.7) High Aggression = 8 (sd 0.8) |

100% (n = 17) male | Children's mental health hospital. | Not reported | 65% (n = 11) mood disorder, 53% (n = 9) ADHD. Range of other disorders in minority including PTSD, oppositional defiant disorder, disruptive behaviour disorder. | Atypical antipsychotic 76.5% (n = 13), Bupropion 29% (n = 5), clonidine/ guanfacine 29% (n = 5), stimulant 41% (n = 7) | Cross-sectional | BMI, Weight, Height | BMI for young boys was within the healthy range. |

| Boxer et al., (2007) [29] USA |

Individuals aged between 10 and 17 years admitted to secure publically funded inpatient psychiatric hospital in the Midwest USA, most of the sample had a mood disorder. | 484 | 13.9 (sd 2.1) | 47% female (n = 227), 53% male (n = 257) | Secure psychiatric facility for young people. | 97.4 days (sd 117.9) | 63% (n = 305) Mood Disorder, 15% (n = 73) thought disorder, 12% (n = 58) behavioral disorder, 4% (n = 19) PTSD | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | BMI | Average BMI for the sample was above the healthy weight range. |

| Bustan et al., (2018) [30] Israel |

Adolescents aged 10–19 hospitalized to an acute adolescent ward without any evidence of affective episodes (depressive, manic, hypomanic or mixed), all patients classed as either psychotic or non-psychotic. | 366 | Psychosis Group = 15.9 (sd 1.6) Non-Psychosis Group = 14.7 (sd 1.8) |

47% female (n = 172), 53% male (n = 194) | Adolescent acute ward at the Geha Mental Health Centre, a regional mental health centre with a catchment area of approximately 500,000 inhabitants. | Psychosis Group = 81.5 days (sd 98.9) Non-Psychosis Group = 42.2 days (sd 60.5) |

Psychosis Group mainly schizophrenia (87.7%, n = 71); Non-Psychosis Group = conduct/ADHD (47.7%, n = 136), adjustment disorders (24.6%, n = 70), neurodevelopmental but hospitalized due to non-psychotic behavioral deterioration (15.1%, n = 43) | Antispychotics for Psychosis Group 33.3% (n = 27), Non-Psychosis Group 33.7% (n = 93) | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | BMI, Weight, Tobacco Use | 24.9% young people smoked and individuals with non-psychotic disorders had slightly higher average BMI scores than psychotic disorders (although both were within the healthy weight range). |

| Carney et al., (2019) [19] UK |

Adolescent inpatients aged 13–18 in generic or secure mental health inpatient unit in the UK, presenting with a range of complex mental health needs which cannot be met safely within the community. | 50 | 15.84 (sd 1.46) | 52% female (n = 26), 48% male (n = 24) | Mixed gender generic adolescent inpatient service providing evidence based treatments for young people with complex mental health needs. Additionally, young person male forensic unit which is a specialised national medium secure inpatient service for adolescents who have needs that cannot be met safely within the community. | 49 days (sd 44.1) | Primarily mood disorders (MDD) (n = 9, 18%), adjustment disorders (n = 8, 16%) and mixed anxiety/ depressive disorders (n = 7, 14%); also autism/asperger (n = 4, 8%); ADHD (n = 3, 6%), psychotic disorders (n = 3, 6%), conduct disorders (n = 3, 6%), ED (n = 2, 4%), anxiety disorders (n = 2, 4%), OCD (n = 1, 2%), LD (n = 1, 2%), intentional feigning of symptoms (n = 1, 2%) | 66% (n = 33) prescribed medication on admission | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | BMI, Weight, Height, BP, HbA1C, Plasma, Lipids, TG, HDL, Prolactin, Physical Activity, Diet, Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | Evidence for poor physical health including high levels prolactin, obesity, and dysregulated blood metabolites. Smoking rates higher than UK average. |

| Clark et al., (1990) [31] USA |

Adolescents aged 15–18 who were admitted to a psychiatric inpatient practice, compared with age matched students from local high schools. | 264 | Not reported. Range 15–18 |

100% male (n = 264) | Adolescent inpatient unit at one of two metropolitan psychiatric hospitals in Chicago, USA. | 75 days | Not reported | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Comparative study) | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | Individuals in adolescent inpatient facilities had high levels of smoking and history of alcohol use and abuse. |

| Dosman et al., (2002) [32] Canada |

34 young people admitted to intermediate psychiatric inpatient services aged 6–12. | 34 | Not reported. Range 6y8m – 12y9m |

15% female (n = 5), 85% male (n = 29) | Intermediate psychiatry inpatient services. | Not reported | ODD (32%, n = 11), ADHD (11.8%, n = 4), Tourettes (8.8%, n = 3), Depression (8.8%, n = 3), SZ (5.9%, n = 2), BP, GAD, BPD, (all 2.9%%, n = 1), | 1.2 psychotropic medications per patient | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | Obesity rates | High rates of obesity and increased weight associated with the use of psychotropic medication in a young sample of psychiatric inpatients. |

| Dullur et al., (2012) [33] Australia |

50 consecutive admissions to an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit aged between 13 and 17. | 50 | 15.75 | 78% female (n = 39), 22% male (n = 11) | Adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit in Australia. | Not reported | MDD (50%, N = 25), BP (16%, n = 8), psychotic disorder (10%, n = 5), BPD (36%, n = 18) | 66% (N = 33) SGAs | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | BMI, Obesity rates, Rate of Metabolic Syndrome, Physical Activity, Tobacco Use, | New admissions to adolescent inpatient units had high rates of obesity, metabolic syndrome and risk factors for metabolic syndrome which was higher in people taking SGAs. |

| Eapen et al., (2012) [18] Australia |

107 adolescents aged 10–18 admitted to two inpatient mental health units over 12 months. | 107 | Not reported. 3.7% (n = 4) 10–12 years 41% (n = 44) 13–15 years 55% (n = 59) 16–18 years |

73.9% female (n = 79), 26.1% male (n = 28) | Two inpatient mental health units in Australia. | Not reported | Not reported | Any medication for mental health 71% (n = 76), SGA 49.5% (n = 53) | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | BMI, BP, Raised Blood Sugar, TG, HDL, Risk factors for MS, Physical Activity | 53% had one of more risk factors for adverse health outcomes. |

| Ford et al., (2009) [34] USA |

397 consecutive admissions to a child psychiatric inpatient unit for long term residential care, classified as high-risk and seriously emotionally disturbed. | 397 | 13.4 (sd 2.6) | 19% female (n = 75), 81% male (n = 312) | Not-for profit residential inpatient treatment centre for high risk and emotionally disturbed young people aged betwee 6 and 19 in USA. | Not reported | Internalising disorder (56%, n = 60), disruptive behaviour (74%, n = 79), psychotic disorders (15%, n = 16), developmental disorders (41%, n = 44), SUD (20%, n = 21) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | BMI | Young people at the facility had an average BMI at the higher end of normal. |

| Garner et al., (2008) [35] Australia |

32 young people recently admitted to inpatient units with a range of psychiatry diagnoses who were taking part in a non-randomised trial of TAU v TAU plus massage therapy, all aged 15–25. | 32 | TAU = 20.1 (sd 1.7) MT = 20.9 (sd 2.3) |

47% female (n = 15), 53% male (n = 17) | Youth health inpatient unit in Melbourne, service for young people aged 15–25, providing medical and behavioral therapies to young people with a range of serious mental illnesses. | (at time of study) TAU 9.7 days (sd 3.3), MT 9.3 days (sd 7.6) | Non-affective psychosis (31%, n = 10), affective psychosis (12.5%, n = 4), mood disorders (25%, n = 8), BP (9.3%, n = 3), substance induced psychosis (3.1%, n = 1), BPD (15.6%, n = 5), other (3.1%, n = 1) | Not reported | Non-randomised trial | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | High rates of smoking and alcohol use in a young inpatient sample |

| Grover et al., (2015) [36] India |

54 adolescents with severe mental illness admitted to an inpatient unit. | 54 | 16.4 (sd 1.9) | 38.9% female (n = 21), 61.1% male (n = 33) | Adolescent inpatient unit in India | Not reported | Psychotic disorder (48.1%, n = 26), affective psychosis (51.9%, n = 28), BP (35.2%, n = 19), MDD (!6.7%, n = 9) | Antipsychotics 77.8% (n = 42), antidepressant 24.1% (n = 13), mood stabliser 33.3% (n = 18) | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | BP, Waist Circumference, Elevated Blood Sugar, HDL, MS | Individuals admitted to mental health inpatient units in India had high levels of MS, and signs of poor physical health. |

| Grudnikoff et al., (2019) [37] USA |

Consecutive admissions to a freestanding psychiatric hospital, including single hospitalizations and readmissions | 999 | 14.6 (sd 2.7) | 59.4% female (n = 583), 41.6% male (n = 416) | Freestanding psychiatric hospital in NY containing one preadolescent unit (5–12.9y) and 3 adolescent units (13–17.9y) | Single hospitalization 7.4 days (sd 6); First time readmission 13.4 days (sd 13.4) | Depressive disorders 49.5% (n = 494), BP 40.2% (n = 402), psychotic disorders 4.6% (n = 46), ADHD 2.8% (n = 28), PTSD 0.5% (n = 5), ID/PDD 0.7% (n = 7), Other 1.7% (n = 17) | 48.7% (n = 486) discharged on antipsychotic medication | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | Obesity Rate | Low rate of obesity for new admissions. |

| Guillon et al., (2007) [38] France |

223 adolescents receiving a first admission to specialised adolescent inpatient unit in France | 223 | Female 16.54 (sd 1.79), Male 16.39 (sd 2.03) | 62.78% female (n = 140), 37.22% male (n = 83) | Specialised adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit | Not reported | MDD 15.7% (n = 35), anxiety disorders e.g. PTSD, panic disorder 15.7% (n = 35), psychotic disorders 14% (n = 31), ED 4% (n = 9), conduct disorders 50.6% (n = 113) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco Use | High rates of smoking in newly admitted adolescent to an inpatient unit |

| Haw et al., (2012) [39] UK |

95 individuals in a psychiatric medium secure service for adolescents and young people between 14 and 21 | 95 | 17^ | 48.4% female (n = 46), 51.6% male (n = 49) | Independent charity providing specialist psychiatric inpatient treatment, containing 2 medium secure units for adolescents and young people, with severe mental illness or conduct disorder, and some for mild LD | 1 year^ (0.1–4.3) | Not reported | Antipsychotic 76.8% (n = 73), mood stablisers 34.7% (n = 33) | Cross-sectional (Routine data) | BMI, Weight, Cholesterol, Hypertension | Obesity levels high and associated with antipsychotic medication. |

| Hulvershorn et al., (2017) [40] USA |

74 consecutive patients on psychotropic medication admitted to Psychiatric Children's Centre aged 5–16 with severe emotional disturbances | 74 | 11.9 (sd 2.37) | 25% female (n = 20), 75% male (n = 54) | Small inpatient hospital for children 5–16 years with severe emotional disturbances, offering high intensity interventions to manage severe emotional disturbances | 218.66 days (sd 124.12) | ODD 88.9% (n = 64), ADHD 55.6% (n = 40), anxiety 56.9% (n = 41), borderline intellectual functioning 4.17% (n = 3) | Antipsychotics 91.7% (n = 66), stimulants 43.1% [31], antidepressants 33.3% (n = 24), mood stabilisers 41.7% (n = 30), non-stimulant therapy for ADHD 73.6% (n = 53) | Retrospective (Cohort) | BMI, Weight, Height, BP, Glucose, Hba1c, HDL, LDL, Cholesterol, Triglycerides, Co-morbid conditions, Tobacco/Alcohol Use | High BMI of young people on admission to the unit, discontinuation of antipsychotic medication resulted in metabolic symptom improvement. |

| Ilomaki et al., (2005) [41] Finland |

278 individuals aged 12–17 admitted to adolescent unit with a range of mental health conditions | 278 | 15.6 (sd 1.3) | 58.7% female (n = 163), 41.3% male (n = 115) | University hospital adolescent unit for individuals 12–17 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco use, Alcohol use | High rates of smoking and alcohol use in a young person inpatient sample. |

| Juutinen et al., (2008) [42] Finland |

323 adolescents with no past or present psychiatric medication 12–17 years admitted to psychiatric inpatient care in Northern Finland | 323 | Female 15.3 (sd 1.4), Male 15.2 (sd 1.4) | 58% female (n = 188), 42% male (n = 135) | University hospital in Northern Finland for adolescents who require acute psychiatric hospitalization in a closed ward | Not reported | FEP 2.2% (n = 7), Conduct disorder 2.2% (n = 7), affective disorders 9.9% (n = 32), anxiety disorders 1.2% (n = 4), other 3.7% (n = 12) | No past or present medication | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Weight, Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | High BMI for individuals admitted to the unit who had not had any previous or current medication. |

| Keeshin et al., (2013) [43] USA |

1434 young people consecutively admitted to an acute care inpatient mental health facility over 10 months | 1434 | 13.7 | 46.7% female (n = 460), 53.3% male (n = 522) | Acute care inpatient psychiatric unit providing support and treatment to children age 3–20 years | Not reported | mood disorders 49.6% (n = 20), anxiety disorders (all) 25.4% (n = 39) [PTSD 18.1% (n = 54)], Disruptive behaviour 40.5% (n = 24), SUD 6.6% (n = 149) | Antipsychotic medication 34.2% (n = 336) | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | BMI | Almost half the sample were either overweight or obese. |

| Khan et al., (2009) [44] USA |

49 young people hospitalized for a range of axis 1 disorders and receiving antipsychotic medication | 49 | 13 years [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]] | 26.5% female (n = 13), 73.5% male (n = 36) | Child and adolescent inpatient unit at Austin state hospital USA | Not reported | % not reported, but included BP, MDD, mood disorder not specified, schizoaffective disorder, SZ, schizophreniform disorder | 51% (n = 25) olanzapine, 49% risperidone (n = 24) | Cohort (non-randomised trial) | BMI, BP, Blood Glucose, TG, HDL, LDL, MS, Tobacco Use, | Young people admitted to inpatient units who were prescribed olanzapine or risperidone had significant amounts of weight gain and increased blood pressure. |

| Laakso et al., (2013) [45] Finland |

300 female adolescents admitted to a psychiatric hospital age 12–17 | 300 | Not reported. | 100% female (n = 300) | Closed adolescent psychiatric ward | Not reported | % not reported, but included affective disorders, anxiety disorders, ED | Not specified | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Weight, Physical Activity | Over 35% female inpatients were overweight |

| Le et al., (2018) [46] USA |

Young people under 18 receiving neuroleptic medication within a child and adolescent psychiatric hospital (CAPH), or paediatric inpatient medical hospital | 152 | Not reported⁎ | CAPH: 54% female (n = 50), 46% male (n = 42) Medical: 38% female (n = 23), 62% male (n = 37) |

Paediatric inpatient settings including paediatric general, ICE, emergency department and adolescent psychiatric hospital unit | Not reported | ASD 2% (N = 3), BP and related disorders 5% (n = 6), SZ and other psychotic disorders 9% (n = 11), Tic disorder 2% (n = 2), Disruptive/conduct disorder 6% (n = 7), anxiety disorder 3% (n = 4), MDD 13% (n = 16), ED 2% (n = 3), Sleep-wake disorder 5% (n = 6), mood disorder NOS 36% (n = 45), agitation 8% (n = 10), impulsivity 3% (n = 4), none of the above 2% (n = 3), unspecified 3% (n = 4) | 65% antipsychotic medication (n = 60); aripiprazole 25% (n = 41), clozapone 2% (n = 4), lurasidone 1% (n = 2), olanzapine 5% (n = 8), quetiapine 13% (n = 22), risperidone 10% (n = 16), ziprasidone 4% (n = 7) | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Obesity, Elevated Lipids | Over half the sample admitted to the child and adolescent inpatient unit were obese |

| Makikyro et al., (2004) [47] Finland |

153 adolescents admitted to an inpatient unit in Finland, aged between 12 and 17 | 153 | Not reported | 55.4% females (n = 87), 44.6% males (n = 70) | Adolescent inpatient unit | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco Use | High rates of smoking in adolescent inpatient |

| Martin et al., (2000) [48] USA |

70 adolescent inpatients from the largest psychiatric inpatient facility for children and adolescents in Connecticut USA, either medicated or non-medicated | 70 | Risperidone: 12.5 (2.4 sd.) Control: 13.5 (2.9 sd.) |

37.1% females (n = 26), 62.9% males (n = 44) | Largest psychiatric inpatient facility for children and adolescents in Connecticut. | Not reported | Psychosis 15.7% (n = 11), affective disorders 42.9% (n = 30), anxiety 32.9% (n = 23), disruptive disorders 81.4% (n = 57), PDD 11.4% (n = 8), polysubstance abuse 2.9% (n = 2), ED 2.9% (n = 2) | Valproate 45.7% (n = 32), SSRI 24.3% (n = 17), stimulant 20% (n = 14), Alpha-2 agonist 20% (n = 14), neuroleptics 12.9% (n = 9) | Cross-sectional (comparative study) | BMI, Weight | Significant weight gain associated with medicated individuals compared with non-medicated |

| Masroor et al., (2019) [49] USA |

800,614 adolescent inpatients (12-18 years) from the Nationwide Inpatient sample from 4411 hospitals and 45 states in the USA | 800,614 | Not reported | 57.75% females (n = 462,366), 42.25% males (n = 338,248) | Nationwide survey of 45 inpatient adolescent mental health facilities in the USA | Not reported | Conduct disorder 1.1% (n = 8885), other diagnoses not specified | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Retrospective cohort) | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | Significantly higher rates of tobacco and alcohol use disorders in people with conduct disorder compared with those without |

| McCloughen et al., (2015) [50] Australia |

56 young people (16–25 years) from two acute mental health units in Australia for people with a diagnosed mental illness admitted voluntarily and involuntarily | 56 | Not reported | 35.7% females (n = 20), 62.3% males (n = 36) | Two acute mental health units; one adolescent (12-17y) and one youth (17-26y) within a large Australian public general hospital for patients with acute mental and behavioral disturbances. | Not reported | Mood disorder 48% (n = 27), psychotic disorder 46% (n = 26), anxiety 26.8% (n = 15), developmental disorders 10.7% (n = 6), ADHD 5.4% (n = 3), personality disorder 5.4% (n = 3), ED 1.8% (n = 1) | One medication 48% (n = 27), two medications 41% (n = 23); most common antidepressants 39% (n = 22), antipsychotics 70% (n = 39), anticonvulsants 14% (n = 8), mood stablisers 7% (n = 4) and combination 5% (n = 3) | Cross-sectional | Co-morbid Physical Health Conditions, Physical Activity, Dietary Intake, Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | Health risk behaviours (e.g. smoking, physical inactivity) common in young inpatient sample |

| McManama O'Brien et al., (2018) [51] USA |

50 young people (14–17 years) from inpatient psychiatry service of a general paediatric hospital | 50 | 15.8 (0.95 sd.) | 80% female (n = 40), 20% males (n = 10) | Inpatient psychiatry service of a general paediatric hospital in North East USA, all receiving treatment for a suicide plan or attempt | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | RCT | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | High rates of tobacco use in a sample of young people receiving treatment for suicidal ideation/attempts. |

| Midbari et al., (2013) [52] Israel |

Young people under 13 years hospitalized in a psychiatric ward treated with clozapine or other psychoactive medication | 36 | Clozapine: 10.4 (2 sd.); Non-Clozapine 10.1 (1.4 sd.) | 11.1% females (n = 4), 88.9% males (n = 32) | Department of child psychiatry in a mental health centre in Israel all receiving treatment for childhood onset schizophrenia | Time from initiation of clozapine treatment to discharge 332.9 days (sd 200.5);Non-clozapine 291.7 days (sd 157) | 100% childhood onset SZ, also OCD 14% (n = 5), ADHD 63.8% (n = 23), ODD 11.1% (n = 4), anxiety 16.7% (n = 6), pervasive developmental disorder 16.7% (n = 6) | All on antipsychotic medication; clozapine 47.2% (n = 17), risperidone 50% (n = 18), olanzapine 30.6% (n = 11), quetiapine 13.9% (n = 5), perphenaize 13.9% (n = 5) | Cross-sectional (Retrospective Chart Review) | TG, Cholesterol, Bilirubin, Tachychardia | Hematological abnormalities within 4–16 weeks of initiation of clozapine with elevated rates at the start. |

| Nargiso et al., (2012) [53] USA |

106 adolescents hospitalized in a psychiatric inpatient facility in North East USA | 106 | 13.6 (0.74 sd.) | 67% females (n = 71), 33% males (n = 35) | Psychiatric inpatient facility | Not reported | MDD 32% (n = 34), conduct disorder 32% (n = 34) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | Tobacco Use | High rates of tobacco use associated with conduct problem symptoms. |

| Niethammer et al., (2007) [54] Germany |

70 adolescent psychiatric inpatients in a hospital in Germany | 70 | Not reported | 66% females (n = 39), 44% males (n = 31) | Adolescent inpatients in the clinic for child and adolescent psychiatry in Germany | Not reported | SUD 37% (n = 26) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | High rates of substance use and dependence in adolescent inpatient populations. |

| Paruk et al., (2009) [55] South Africa |

70 adolescents admitted to adult psychiatric wards over a 2 year period | 70 | 16.79 (1.27 sd.) | 20% females (n = 14), 80% males (n = 56) | General psychiatric ward, adult ward with adolescents admitted. | 27.8 days (23.8 sd.) | FEP 64.3% (n = 45), previous psychosis 35.7% (n = 25). Brief psychotic disorder 5.7% (n = 4), schizophreniform disorder 27.1% (n = 19), SZ 30% (n = 21), organic psychosis 10% (n = 7) | All on antipsychotics; FGA 85.7% (n = 60), SGA 15.5% (n = 10). Benzodiazepine 58.6% (n = 41), anticholinergic 41.4% (n = 29) | Cross-sectional (Naturalistic, Retrospective Cohort) | Glucose, Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | Very high rates of tobacco and alcohol use. |

| Patel et al., (2007) [56] USA |

95 children and adolescents hospitalized for psychiatric reasons | 95 | 14 (3 sd.) | 43% females (n = 41), 57% males (n = 54) | Paediatric psychiatric inpatient ward at a Children's Hospital Medical Centre receiving antipsychotic medication. | Not reported | BP 52% (n = 49), disruptive behaviour disorder 46% (n = 44), anxiety 39% (n = 37), MDD 26% (n = 25), developmental disorder 25% (n = 24), psychotic disorder 14% (n = 13) | One medication 73% (n = 69), more than one medication 27% (n = 26). Antidepressant 47% (n = 45), mood stabliser 45% (n = 43), psychostimulant 28% (n = 27) | Cross-sectional (Retrospective Cohort) | BMI, Cholesterol, LDL, HDL, TG | The prevalence of overweight children and adolescents taking antipsychotic medication was triple the national norms, and high rates of lipids were common. |

| Preyede et al., (2018) [57] Canada |

161 young people hospitalized for psychiatric care in regional hospital | 161 | 15.42 (1.4 sd.) | 72% females (n = 124), 23% males (n = 37) | Youth currently receiving psychiatric care at a child and adolescent psychiatry unit. | Not reported | MDD 57% (n = 91), adjustment disorder 14% (n = 22), ADHD 11% (n = 17), social anxiety 9% (n = 14), SUD 7% (n = 11), GAD 6% (n = 10) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Physical Activity, Dietary Intake | Young people reported engaging in little physical activity and low levels of fruit and veg intake. |

| Riala et al., (2009) [58] Finland |

508 adolescent inpatients admitted to a psychiatric unit in Finland | 508 | 15.4 (1.3 sd.) | 59.1% females (n = 300), 40.9% males (n = 208) | Acute psychiatric hospital in a closed ward. | Not reported | SUD 38.2% (n = 194), anxiety disorders 23.8% (n = 121), affective disorders 47% (n = 239), conduct disorders/ODD/ADHD 44.7% (n = 227), psychotic disorders 10.6% (n = 54) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco Use | Very high levels of tobacco use and suicide attempts and self-harm higher in smokers than nonsmokers. |

| Riala et al., (2011) [59] Finland |

171 adolescent inpatients with conduct disorder admitted to a psychiatric unit in Finland | 171 | Female: 15.5 (1.29 sd); Male: 15.3 (1.44 sd) | 42.1% females (n = 72), 57.9% males (n = 99) | Acute psychiatric hospitalization in a closed ward | Not reported | All conduct disorder 100% (n = 171) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco Use, Substance Use | High levels of tobacco use which was associated with conduct disorder symptoms. |

| Turniansky et al., (2019) [60] Israel |

78 adolescent female inpatients with borderline personality disorder admitted to an adolescent inpatient unit | 78 | 15.1 (1.7 sd) | 100% female (n = 78) | Adolescent inpatient unit for treatment of psychiatric disorders in youth | 114.5 days current (198 cumulative) | All BPD 100% (n = 78) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Retrospective Cohort) | Tobacco Use, Alcohol Use | More than half used tobacco and alcohol. |

| Upadhyaya et al., (2003) [61] USA |

120 young people admitted to a child and adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit | 120 | 13.7 (2.46 sd) | 46.7% female (n = 56), 53.3% (n = 64) | Child and adolescent inpatient psychiatric unit | Not reported | MDD 41.7% (n = 50), conduct disorder 7.5% (n = 9), PTSD 9.2% (n = 11), BP 9.2% (n = 11), ODD 37.5% (n = 45), 30% (n = 36) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | Tobacco Use | High rates of tobacco use in adolescent inpatients. |

| Vieweg et al., (2005) [62] USA |

300 new admissions to a large private psychiatric facility | 300 | 14.2 (2.9 sd.) | 50.3% females (n = 151), 49.7% males (n = 149) | Private child and adolescent psychiatric facility in the USA | Not reported | Mood disorder 92% (n = 276), psychotic disorder 8% (n = 24) | Antipsychotics 24.3% (n = 73); Aripiprazole 0.33% (n = 1), haloperidol 0.33% (n = 1), chlorpromazine 4.3% (n = 13), olanzapine 4.7% (n = 14), ziprasidone 1% (n = 3), quetiapine 6% (n = 18), risperidone 10.3% (n = 31) | Cross-sectional (Cohort) | BMI | Children and adolescents with mental illness in the inpatient unit had higher BMI than general paediatric population. |

| Weaver et al., (2007) [63] USA |

636 adolescent inpatients admitted to two different facilities in USA age 12–18 | 636 (Site 1: n = 316; Site 2: n = 320) | Not reported | 51.3% females (n = 326), 48.7% males (n = 310) | University operated facility and a state operated facility admitting children and adolescents in need of acute-care crisis stabilization | Not reported | Mood disorder 72.3% (n = 460), anxiety 25.2% (n = 160), psychotic disorder 6.3% (n = 40), adjustment disorder 8.3% (n = 53), child disruptive disorder 40.3% (n = 256), SUD 27.8% (n = 177) | Not reported | Cross-sectional (Retrospective Cohort) | Tobacco Use, Substance Use | High rates of substance use disorders and tobacco use in young people admitted to inpatient units. |

Abbreviations: ADHD (Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder); ASD (autistic spectrum disorder); BMI (body mass index); BP (blood pressure); BPD (borderline personality disorder); CNS (central nervous system); ED (eating disorder); FEP (first episode psychosis); FGA (first generation antipsychotics); GAD (generalised anxiety disorder); HDL (high density lipoprotein); LD (learning difficulties); LDL (low density lipoproteins); MS (metabolic syndrome); MT (massage therapy); OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder); ODD (oppositional defiant disorder); PDD (persistent depressive disorder); PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder); RCT (randomised controlled trial); SD (standard deviation); SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor); SUD (substance use disorder); SGA (second generation antipsychotics); SZ (schizophrenia); TAU (treatment as usual); TG (triglycerides).

Median provided not mean.

Range?

4.2. Clinical cardiometabolic risk

A range of clinical cardiometabolic physical health measures were reported in the studies, and weighted averages/pooled prevalence rates can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis Results.

| Cardiometabolic risk factor | Number of studies^ | Total sample size | Pooled prevalence rate | Weighted average (estimate, standard error) | 95% CI | Cochrane's Q | I2 | Comparison with general population or healthy ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health measures | ||||||||

| Weight: Overweight Prevalence (%) | 10 | 2789 | 32.4% | – | 26.1%–39.5% | 85.79 (9) | 89.51 | Health Service England (2018); general population overweight or obese 31% boys, 27%girls |

| Weight: Obese Prevalence (%) | 5 | 2612 | 15.5% | – | 4.5%–41.6% | 229.38 (4) | 98.26 | Health Service England (2018); general population obese 17% boys, 15% girls. |

| BMI⁎ | 11 | 1681 | – | 23.96 (0.60) | 22.79–25.13 | 199.13 (15) | 92.47 | Underweight: 18.5 or less; Normal weight: 18.5–24.9;Overweight: 25–29.9; Obese: 30 or more |

| Weight⁎ (kg) | 4 | 197 | – | 46.60 (5.65) | 35.52–57.67 | 126.35 (6) | 95.25 | n/a |

| Blood Pressure – Systolic | 3 | 163 | – | 114.06 (3.87) | 106.48–121.64 | 63.18 (4) | 93.67 | 120–136 (Livestrong, 2017) |

| Blood Pressure – Diastolic | 3 | 163 | – | 69.87 (1.46) | 67.01–72.73 | 13.58 (4) | 70.56 | 82–86 (Livestrong, 2017) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 3 | 161 | – | 97.70 (15.3) | 67.26–128.14 | 34.77 (4) | 88.50 | <150 mg/dL (WHO, Goodman et al., 2004) |

| Elevated Triglycerides (%) | 3 | 193 | 23.1% | – | 9.2%–47.3% | 11.86 (2) | 83.14 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 3 | 161 | – | 45.87 (2.04) | 41.88–49.86 | 14.11 (4) | 71.65 | >35 mg/dL (WHO, Goodman et al., 2004) |

| Abnormal HDL (%) | 2 | 161 | 24.9% | – | 4.8%–68.5% | 21.91 (1) | 95.44 | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 3 | 161 | – | 97.39 (2.99) | 91.54–103.24 | 5.26 (4) | 23.95 | <130 mg/dL (WHO, Goodman et al., 2004) |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 2 | 112 | 169.81 (4.12) | 161.73–177.88 | 2.19 (2) | 8.93 | <170 mg/dL (WHO, Goodman et al., 2004) | |

| Elevated Cholesterol (% <5 mm/L) | 2 | 116 | 9.8% | – | 1.2–48.5 | 4.57 (1) | 78.11 | |

| Physical health behaviours | ||||||||

| Physical Activity (% Active)# | 4 | 263 | 45.9% | – | 23%–70.6% | 38.89 (3) | 92.29 | Recommended 60 min per day of moderate to vigorous exercise (WHO, 2011), and NHS England (2019) found 47% children and young people meet current guidelines. |

| Smoking Prevalance (%)~ | 19 | 804,018 | 51.5% | – | 32.3%–70.2% | 4359.6 (18) | 99.59 | NHS England (2019) 6% young people current smokers and 3% regular smokers. |

| Lifetime Smoking Prevalence (%) | 4 | 374 | 57.9% | – | 34.5%–78.2% | 47.96 (3) | 93.75 | NHS England (2019) 19% tried smoking at least once in their life. |

| Current Alcohol Use Prevalence (%) | 7 | 878 | 67.8% | – | 48.3%–82.6% | 118.78 (6) | 94.95 | NHS England (2019) 38% drank alcohol at least a few times in the past year and 44% had consumed alcohol in the past. |

| Alcohol Abuse/Dependence Prevalence (%) | 3 | 800,948 | 7.3% | – | 3.9%–13.1% | 12.09 (2) | 83.45 | |

^meta-analyses may have contained more individual samples as some studies reported more than one sample (e.g males/females, diagnoses).

Removal of much younger sample (Barzman), BMI: 24.49 (se. 0.60), 95% CI (23.28–25.63), Q = 178.79 ([13], I292.73; Weight: 51.86 kg (se. 6.38), 95% CI (39.34–64.37), Q = 88.23 [4], I2 95.47.

Removal of self-report activity (Carney et al., 2019) due to methodological issues: 33%, 95% CI (18.4–51.9), Q = 12.57 [2], I2 84.08.

Removal of largest cohort (n = 800,614), 53%, 95% CI (43.2%–62.6%), Q = 434.45 [17], I2 96.09.

4.3. Overweight/obesity prevalence

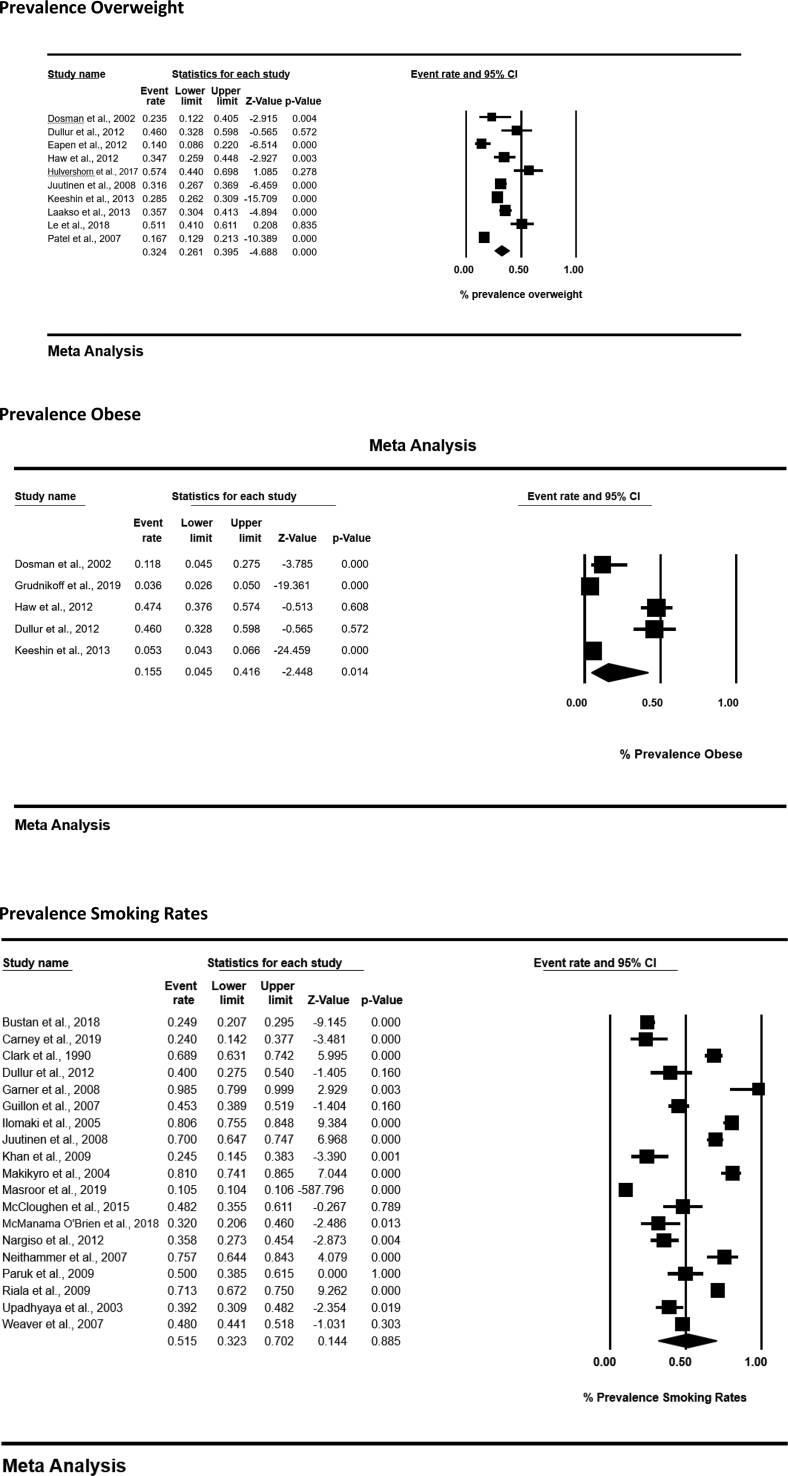

Eleven studies reported the prevalence of obesity or overweight status (n = 3829), according to BMI values [18,32,33,37,39,42,43,45,46,56,62]. In the ten studies which permitted meta-analyses, the pooled prevalence rate of young people who were overweight (BMI > 25) was 32.4% (95% CI 26.1%–39.5%; n = 2789), and individuals who were obese (e.g. BMI > 30) was 15.5% (95% CI 4.5%–41.6%; n = 2612), higher than general population estimates [64]. (See Fig. 2.)

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis forest plots.

Eleven studies reported BMI values (n = 1731), ranging from 18.2–32.5 [19,28,29,33,34,39,40,44,48,56]. The weighted average was 23.96 (95% CI 22.79–25.13), and fell within the healthy weight range (18.5–24.9). One sample included younger participants [28], and upon removal of this, the average BMI increased to the upper end of the healthy weight range, 24.49 (95% CI 23.28–25.63). Only one study had a healthy control group [39], and average BMI was significantly higher among CAMHS inpatients than controls (27.6 v 22.2).

Four studies reported bodyweight (n = 197), ranging from 32.8–68.58 kg [19,28,40,48]. The weighted average was 46.6 kg (95% CI 35.52–57.67 kg). Two studies reported weight at different time-points and 24.3% gained more than 5% of their body weight in 3 months in one sample [39], and 84% gained weight over 6 months in another [19].

One paper reported central adiposity. 37% of young people had elevated waist circumference compared with healthy recommendations [36].

4.4. Blood pressure

Five studies reported blood pressure (n = 324), [18,19,28,36,44]. The weighted average systolic BP was 114.06 (95% CI 106.48–121.64; N = 163), and diastolic was 69.87 (95% CI 67.01–72.73; N = 163), both within the healthy range for adolescents and young people (120–136 systolic, 82–86 diastolic [65]. However, two studies reported rates of clinical hypertension, which ranged from 11% [36] to 35.2% [18].

4.5. Carbohydrate metabolism-related biomarkers

Five studies reported carbohydrate metabolism-related biomarkers (n = 358), [18,19,36,40,44]. The mean fasting blood glucose ranged from 83.8–89.3 mg/dL [44], and 13% had raised fasting blood glucose [36]. Mean random glucose ranged from 81.4–89.36 mg/dL [40,44], and the amount of people with elevated blood sugars varied between 3% [18] and 18.6% [44]. Mean Hba1c was 34.19 mmol/L, and ranged from 24 to 42 mmol/L [19].

4.6. Lipid/blood related biomarkers

Non-fasted lipid and blood related biomarkers were reported across nine studies. Triglycerides were the most commonly reported [18,19,33,40,44,52,56]. Weighted average triglycerides were 97.7 mg/dL (95% CI 62.26–128.14; N = 161), and pooled prevalence rate of elevated triglycerides was 23.1% (95% CI 9.2–47.3; N = 193). According to the WHO, healthy triglyceride levels are below 150 mg/dL [66].

HDL levels were reported in six studies [18,19,36,40,44,56]. Weighted average HDL was 45.87 mg/dL (95% CI 41.88–49.86; N = 161), and pooled prevalence rate of low HDL was 24.9% (95% CI 4.8–68.5; N = 161). LDL was reported in three studies [40,44,56]. Weighted average LDL was 97.93 mg/dL (95% CI 91.54–103.24; N = 161). Cholesterol was reported in four studies [39,40,52,56]. Weighted average cholesterol was 169.81 mg/dL (95% CI 161.73–177.88; N = 112), and pooled prevalence rate of elevated cholesterol (>5 mmol/L) was 9.8% (95% CI 1.2–48.5; N = 116). The average cholesterol markers were all within the healthy range for young people according to the WHO (HDL > 35 mg/dL, LDL < 130 mg/dL, Cholesterol <170 mg/dL; [66].

4.7. Other physical health indicators

Metabolic Syndrome is a cluster of conditions which increases risk of heart disease or stroke and includes the presence of at least three of the following; increased waist circumference, high triglycerides, low HDL, high blood pressure, insulin resistance or high blood sugars. The rate of metabolic syndrome (MS) was reported in three samples, as 4.6% [18], 10% [33] and 13% [36]. The prevalence of young people who displayed at least one criteria for MS was high, ranging between 39 and 53% [18,33,36].

The proportion of young people who had a diagnosed physical health condition varied. In Hulvershorn et al., [40], 53% had a comorbid medical condition, and in McCloughen et al., [50] 30% had at least one (59% of which had multiple conditions). Specific physical health conditions included Tachycardia (heart rate > 100 bpm, 27.8%) [52], diabetes (6.4%) [27];2%, [39], hypertension (2%) [39], and dyslipidaemia (3%) [46].

4.8. Behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors

A range of behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors were reported, including tobacco use, alcohol use, physical activity, and diet.

4.9. Tobacco use

Tobacco use was reported in 19 studies, containing 804,018 individuals [19,30,31,33,35,38,41,42,44,47,[49], [50], [51],[53], [54], [55],58,61,63]. Pooled prevalence rate of tobacco use was 51.5% (95% CI 32.2–70.2; N = 804,018) (see Fig 2). The sample largely comprised of one cohort containing 800,614 individuals [49]; however, removal of this study had minimal effect on the overall figure. (53%). One study reported a control group, and rates of tobacco use were significantly higher in patients (69%) than controls (22%) [31], and higher than general population estimates in the UK for young people (6% currently using tobacco) [67,70].

Several studies contained additional information (Table 3). The average number of cigarettes smoked daily was 11 (range 2–40) [19]. Frequency of tobacco use was reported less often, although up to 86% of some samples smoked daily [59]. Additionally, the average age people started smoking ranged between 10 [19] and 12.3 years [59]. Lifetime use of tobacco was 57.9% (95% CI 34.5–78.2; N = 374).

Table 3.

Frequency and Quantity of Health Risk Behaviours.

| Risk factor | Study | Findings | Summary of risk factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking – Frequency/Quantity | McCloughen et al., 2015 | Never 51.8% (n = 29) Sometimes 16% (n = 9) Most days 1.8% (n = 1) Everyday 30.4% (n = 17) |

Varying rates of daily smokers, but high overall rates. |

| Riala et al., 2009 | 71% smoked at least every day | ||

| Riala et al., 2011 | 86% (n = 147) smoked at least every day | ||

| Carney et al., 2019 | Average quantity 11 per day (range 2–40) | ||

| Alcohol Use – Frequency/ Quantity | McCloughen et al., 2015 | Never 30.3% (n = 17) Sometimes 60.7% (n = 34) Most days 7.1% (n = 4) Everyday 1.8% (n = 1) |

Relatively low frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption. |

| Carney et al., 2019 | Never 80% (n = 40) Monthly 6% (n = 3) 2–4 times per month 8% (n = 4) More than 4 times per week 2% (n = 1) |

||

| Carney et 2019 | Average units per week 1.02 (4.44 sd.), range 0–33 | ||

| Physical Activity – Frequency | McCloughen et al., 2015 | Rarely 23.2% (n = 13) Some days 39.3% (n = 22) Most days 19.6% (n = 11) Everyday 7.1% (n = 4) |

Physical activity relatively infrequent, and low rates of individuals exercising daily or most days, compared with the government guidance to be active 5 days per week. |

| Eapen et al., 2009 | At least an hour for: 5 days per week 19.7% (n = 21) 4 days per week 9.8% (n = 10) 3 days per week 18% (n = 19) 2 days per week 14.8% (n = 16) 1 day per week 19.7% (n = 21) Average 3.5 days per week (1.9 sd.) |

||

| Preyede et al., 2018 | Active on average 1.13 (1.22 sd.) times in past week | ||

| Food Intake – Frequency | McCloughen et al., 2015 | Fruit/vegetable intake Rarely 10.7% (n = 6) Some days 32.1% (n = 18) Most days 35.7% (n = 20) Everyday 21.4% (n = 12) |

Fruit and vegetable intake low, and moderate consumption of junk food, however more rigorous assessments of diet are required. |

| Preyede et al., 2018 | Consumed fruit and vegetable on average 2.66 (1.14 sd.) days in the past week | ||

| McCloughen et al., 2015 | Junk food intake Rarely 12.5% (n = 7) Some days 60.7% (n = 34) Most days 19.6% (n = 11) Everyday 7.1% (n = 4) |

4.10. Alcohol use

Seven studies reported alcohol use (n = 878; [19,35,41,42,50,54,55]. The overall pooled prevalence rate of current alcohol use across these studies was 67.8% (95% CI 48.3–82.6), which is significantly higher than the general population (38% in the past year) [68]. The frequency of alcohol use was described in two studies and varied considerably [19,50]. The average units per-week was reported in one study (1.02 units, s.d. 4.44) [19]. The overall pooled prevalence rates of people who reported alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence was 7.3% (95% CI 3.9–13.1), and ranged in individual samples from 16% to 42% [31,49,54].

4.11. Physical activity

Regular physical activity was reported in five studies [18,19,33,45,50]; pooled prevalence 45.9% (95% CI 23–70.6; N = 263). However, the definitions of being active varied, including self-reported sedentary lifestyle [19]. In one study 62.5% of young people were active on some days or rarely [50], whereas in another they reported being active on average 3.5 days per week [18]. The WHO recommend individuals are active for at least 60 min per day, and NHS England estimate that approximately 47% children and young people currently meet these guidelines [69].

McCloughen et al., [50] reported type of activity. Walking was the most common activity (66.1%, N = 37), followed by running (35.7%, n = 20) and visiting the gym (23.2%, n = 13). Eapen et al., [18] reported young people's views about exercise, and found 32% did not consider their activity levels as important, whereas 29% thought it was at least moderately important. Further, the confidence of people to overcome barriers to engage in activity varied with 30% feeling unable to overcome the barriers, 30% were confident and 40% of the sample were neutral [18].

4.12. Diet

Dietary intake was reported in three studies [19,50,57]. Preyede et al., [57] found young people consumed fruit and vegetables on average just 2.6 days per week. McCloughen et al., [50] on the other hand found 57.1% of their sample consumed fruit and vegetables on most days or every day. The frequency of junk food consumption was generally, “rarely” or “some days” (73.2%) [50].

5. Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine the physical health, via clinical and behavioral cardiometabolic risk factors in young people receiving inpatient mental health care. Findings from this synthesis suggest this population exhibits signs of poor physical health, even at an early stage, during mental health inpatient admissions. Pooled analyses found that almost half of young people were overweight or obese, and over half were tobacco smokers; significantly higher than the general population. Additionally, young people in inpatient mental health settings showed early signs of metabolic risk via elevated blood cholesterol levels, high prevalence of physical health conditions and indicators of metabolic syndrome (e.g dislipidemia, hypertension), as well as increased behavioral risk such as physical inactivity, alcohol use and low consumption of fruit and vegetables.

Our findings are in line with existing literature showing people with SMI are at increased risk for poor physical health from an early stage, [1,2,13]. A large proportion of young people receiving inpatient care were already overweight (32.4%) or obese (15.5%). Whilst beyond the scope of this review to assess whether people gained weight over time, it is concerning, given the vulnerability for weight-gain in this population, for example, if they subsequently receive antipsychotic medication [16,17]. Inpatients are also likely to experience additional restrictions which reduce their opportunities to be active, and thus increase obesity [16,17]. Our previous service evaluation showed that 84% of CAMHS inpatients who had their weight recorded more than once over 6-months gained weight [19]. Although obesity is an issue for the general population, and indeed those with SMI who are treated in the community, young people in inpatient units are a particularly vulnerable group, given that they are likely to experience further weight gain and face significantly more barriers to living a healthy lifestyle.

Tobacco use was also significantly higher than the UK general population, at around 50%, which is higher than both teenage populations (6%) and adults (14.1%) [67]. Smoking tobacco during adolescence is associated with ongoing use into adulthood, and increased likelihood of disease from conditions such as cancers and heart disease [67,70]. Furthermore, intervening early to promote smoking cessation could be beneficial to prevent habits from becoming more engrained. Alcohol use and abuse was also high (68%). This is concerning given the young age of the sample, as use of alcohol at a young age significantly increases risk of cognitive deficits, developmental dysfunction and poor metabolic health in young people [71]. Physical activity rates were lower than recommended for young people. However, relatively few studies reported physical activity levels, and some suffered methodological limitations such as relying on self-report, which is associated with overestimations of activity [72]. This is concerning as engaging in risk behaviours at an early stage is associated with continuation of behaviours into adulthood [70,71].

5.1. Clinical implications

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice. Individuals on mental health units are likely to be prescribed multiple medications which although may provide psychological benefit, also have well documented metabolic side-effects such as weight gain. Whilst we do not recommend clinicians stop prescribing these medications, we do suggest an awareness should be raised regarding the significant cardiometabolic risk that young people are experiencing, and attempts should be made to ameliorate this risk. Early intervention to promote a healthy lifestyle is key to prevent the onset of comorbid conditions, and reduce the long-term impact of engaging in behavioral risk factors [13,73]. Yet, to date there have been relatively few research trials which promote physical health for children and young people with SMI, and particularly those in inpatient units. Our recent review identified just three published international studies conducted in young people's inpatient units; which included sports, gym and yoga interventions [74]. There is preliminary evidence for the efficacy of these studies suggesting physical health interventions benefit not only physical health but also mental health, through improving mood, reducing anxiety and increasing wellbeing. Therefore, inpatient units afford an opportunity to intervene to improve physical health, ameliorate long-term risks and improve mental wellbeing with physical health interventions.

5.2. Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first synthesis of the literature on physical health in child and adolescent inpatient services. The scope of this review was kept intentionally broad and covered a range of international cohorts, to provide a comprehensive overview of physical health and behavioral risk. From this we have identified evidence that young people on inpatient units are at increased risk for poor physical health, and that there is an urgent need to intervene.

The scope of the review meant there was a high degree of heterogeneity between studies in relation to sample (such as age, diagnoses), outcomes, and methodology. This is representative of inpatient services, which are often diverse groups with different needs. However, as different diagnoses were pooled, it is unknown whether these findings apply to individuals with specific conditions, such as ADHD, autism. Whilst we cannot comment on individual diagnoses with this synthesis, we can assume that this group are even more at risk for poor physical health due to illness severity. The design of studies varied, which made direct comparisons difficult and limits our ability to form firm conclusions. Relatively few studies included matched controls which meant we could only compare to general population means, which may not be representative of international cohorts. Additionally, there is a lack of published research on physical health of young people with specific physical health conditions, which meant we were unable to compare with diagnostic groups of young people. Many studies were cross-sectional/observational or low-quality studies, so therefore, we cannot comment on the causal factors for this poor physical health and further research is needed to highlight the reasons driving this increased risk. Finally, measurements were not always standardised (diet/exercise) or reported according to the guidance for young people. For example, WHO recommend that BMI is reported differently for young people and adults, and rather than the usual categories to classify overweight status, young people should be assessed according to the percentile for their height and age [75]. Despite this only one study reported BMI in this manner. Additionally, it was beyond the scope of our review to account for demographic characteristics such as race or ethnic background in our analysis due to differences in reporting across papers. However, despite limitations, there is preliminary evidence to suggest young people on inpatient units, exhibit poor physical health at an early stage.

5.3. Future research

The physical health of young people receiving inpatient care urgently needs addressing. Despite limitations with the heterogeneity of studies included in our review, there is initial evidence that young people receiving inpatient mental health care are exhibiting markers of poor physical health and cardiometabolic risk. Given the vast body of research for adult populations, there is a relative paucity of research for young people, particularly for those with serious mental illness. This is despite existing evidence showing health risks are common at an early stage, and that early intervention is key to prevent the onset of comorbid conditions, and improve the overall wellbeing of young people. Future work should seek to identify causal factors for poor physical health in young people with serious mental illness and identify appropriate interventions. The cross-sectional nature of the studies included meant we were unable to comment on the trajectory of poor physical health and whether this is something exacerbated by specific factors such as restrictions on movement or increased medication on inpatient units. Therefore, high quality long-term prospective studies are needed to identify the trajectory of poor physical health in this population, and identify ways to ameliorate cardiometabolic risk. Further research is needed to fully understand what underpins behavioral risk, using standardised measures of dietary intake and physical activity, and explore the barriers and facilitators to living a healthy lifestyle. Inpatient services offer an opportune time to intervene to focus on the implementation of behavioral interventions with a focus on physical activity, wellness education, nutrition skills and coaching, smoking cessation and motivational based interventions. Additionally, pharmacological interventions to explore include medication reviews, prescription of medications such as metformin for metabolic health and dysfunction. Subsequently, we will be able to establish interventions which are appropriate and effective for young people, and optimise the health care environment to prevent iatrogenic harm and potentially derive better outcomes.

6. Conclusion

This review highlights the vulnerability of young people admitted to inpatient units and emphasises the opportunity to efficiently monitor, treat and intervene early to target poor physical health. Of greatest concern, a large proportion of young people were overweight, and were much more likely to be smokers than the general population. Additionally, young people had elevated levels of cholesterol and blood sugars and health risk behaviours, such as physical inactivity and alcohol use. Whilst beyond the scope of this review to comment on the trajectory of poor physical health, we show that it is neccessary to intervene early with physical health interventions to prevent the onset of comorbid conditions and worsening of poor physical health. Inpatient settings afford the opportunity to embed physical health promotion within clinical care and optimise service delivery for young people.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to conception and planning of the review. RC led on the review and all authors were involved in the interpretation of the results. RC conducted the initial searches and RP/JF assisted with organisation of the search results for review. RC, JF, RP and KL screened articles independently for inclusion. RC and JF extracted data independently, and conducted quality assessments. RC completed the meta-analyses. JF provided statistical expertise and guidance. SP, KL and HL provided clinical expertise and input. RC, JF, HL, and RP provided research expertise. RC wrote the first draft of the manuscript, all authors contributed to the revised drafts and approved the final write up of the completed manuscript.

Declaration of interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This is independent research supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration Greater Manchester. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. JF is supported by a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T021780/1). We also acknowledge Dr. Lydia Pearson for providing a critical peer review prior to this submission.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.De Hert M., Schreurs V., Vancampfort D., Van Winkel R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correll C.U., Solmi M., Veronese N., Bortolato B., Rosson S., Santonastaso P. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):163–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health . Department of Health; London: 2006. Choosing health: supporting the physical needs of people with severe mental illness- commissioning framework. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiers D., Bradshaw T., Campion J. Health inequalities and psychosis: time for action. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(6):471–473. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . 2018. Management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders: WHO guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu N.H., Daumit G.L., Dua T., Aquila R., Charlson F., Cuijpers P. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):30–40. doi: 10.1002/wps.20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firth J., Siddiqi N., Koyanagi A., Siskind D., Rosenbaum S., Galletly C. The lancet psychiatry commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 1;6(8):675–712. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.England N.H.S. National Health Service England; London: 2018. Improving physical healthcare for people living with severe mental illness (SMI) in primary care: guidance for CCGs. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carney R., Cotter J., Bradshaw T., Firth J., Yung A.R. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;170:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney R., Cotter J., Bradshaw T., Yung A.R. Examining the physical health and lifestyle of young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a qualitative study involving service users, parents and clinicians. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordes J., Bechdolf A., Engelke C., Kahl K.G., Balijepalli C. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in female and male patients at risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;181:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bresee L.C., Majumdar S.R., Patten S.B., Johnson J.A. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease in people with schizophrenia: a population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2010;117(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firth J., Carney R., Jerome L., Elliott R., French P., Yung A.R. The effects and determinants of exercise participation in first-episode psychosis: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbaum S., Lederman O., Stubbs B., Vancampfort D., Stanton R., Ward P.B. How can we increase physical activity and exercise among youth experiencing first-episode psychosis? A systematic review of intervention variables. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10(5):435–440. doi: 10.1111/eip.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob C., Baird J., Barker M., Cooper C., Hanson M. WHO; Geneva: 2017. The Importance of a Life Course Approach to Health: Chronic disease risk from preconception through adolescence and adulthood. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faulkner G.E., Gorczynski P.F., Cohn T.A. Psychiatric illness and obesity: recognizing the “obesogenic” nature of an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):538–541. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorczynski P., Faulkner G., Cohn T. Dissecting the obesogenic environment of a psychiatric setting: client perspectives. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2013;32(3):51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eapen V., John G. Weight gain and metabolic syndrome among young patients on antipsychotic medication: what do we know and where do we go? Australas Psychiatry. 2011 Jun;19(3):232–235. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2010.539609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carney R., Imran S., Law H., Folstad S., Parker S. Evaluation of the physical health of adolescent in-patients in generic and secure services: retrospective case-note review. BJPsych Bull. 2020 Jun;44(3):95–102. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2019.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Aug 18;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malla A., Iyer S., McGorry P., Cannon M., Coughlan H., Singh S. From early intervention in psychosis to youth mental health reform: a review of the evolution and transformation of mental health services for young people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016 Mar 1;51(3):319–326. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickwood D., Paraskakis M., Quin D., Hobbs N., Ryall V., Trethowan J. Australia’s innovation in youth mental health care: the headspace centre model. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;13(1):159–166. doi: 10.1111/eip.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawyer S.M., Afifi R.A., Bearinger L.H., Blakemore S.J., Dick B., Ezeh A.C. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. The Lancet. 2012 Apr 28;379(9826):1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson J., Clarke T., Lower R., Ugochukwu U., Maxwell S., Hodgekins J. Creating an innovative youth mental health service in the United Kingdom: the Norfolk Youth Service. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018 Aug;12(4):740–746. doi: 10.1111/eip.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., Tugwell P.J. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Ottawa: 2011. OOHRI. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986 Sep 1;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al Haidar F.A. Inpatient child and adolescent psychiatric referrals in Saudi Arabia: clinical profiles and treatment. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health J. 2003;9(5–6):996–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barzman D.H., Mossman D., Appel K., Blom T.J., Strawn J.R., Ekhator N.N. The association between salivary hormone levels and children’s inpatient aggression: a pilot study. Psychiatric Q. 2013 Dec 1;84(4):475–484. doi: 10.1007/s11126-013-9260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boxer P. Aggression in very high-risk youth: examining developmental risk in an inpatient psychiatric population. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007 Oct;77(4):636–646. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bustan Y., Drapisz A., Dor D.H., Avrahami M., Schwartz-Lifshitz M., Weizman A. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in non-affective psychotic adolescent inpatients: evidence for early association between inflammation and psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2018 Apr 1;262:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark D.C., Sommerfeldt L., Schwarz M., Hedeker D., Watel L. Physical recklessness in adolescence: trait or byproduct of depressive/suicidal states? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990 Jul.;178(7):423–433. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dosman C.F., Senthilselvan A., Andrews D. Psychiatric treatment: a risk factor for obesity? Paediatr Child Health. 2002 Feb 1;7(2):76–80. doi: 10.1093/pch/7.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dullur P., Eapen V., Trapolini T. Metabolic syndrome in an adolescent psychiatric unit. Australas Psychiatry. 2012 Oct;20(5):444–445. doi: 10.1177/1039856212447861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford J.D., Connor D.F., Hawke J. Complex trauma among psychiatrically impaired children: a cross-sectional, chart-review study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 Jun 30;70(8):1155–1163. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garner B., Phillips L.J., Schmidt H.M., Markulev C., O’Connor J., Wood S.J. Pilot study evaluating the effect of massage therapy on stress, anxiety and aggression in a young adult psychiatric inpatient unit. Australian New Z J Psychiatry. 2008 May;42(5):414–422. doi: 10.1080/00048670801961131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grover S., Malhotra N., Chakrabarti S., Nebhinani N., Avasthi A., Subodh B.N. Metabolic syndrome in adolescents with severe mental disorders: retrospective study from a psychiatry inpatient unit. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;14:69–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grudnikoff E., McNeilly T., Babiss F. Correlates of psychiatric inpatient readmissions of children and adolescents with mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Dec 1;282:112596. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guillon M.S., Crocq M.A., Bailey P.E. Nicotine dependence and self-esteem in adolescents with mental disorders. Addict Behav. 2007 Apr 1;32(4):758–764. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haw C., Bailey S. Body mass index and obesity in adolescents in a psychiatric medium secure service. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2012 Apr;25(2):167–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hulvershorn L., Parkhurst S., Jones S., Dauss K., Adams C. Improved metabolic and psychiatric outcomes with discontinuation of atypical antipsychotics in youth hospitalized in a state psychiatric facility. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017 Dec 1;27(10):897–907. doi: 10.1089/cap.2017.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ilomäki R., Kaartinen K.L., Viilo K., Mäkikyrö T., Räsänen P., Ilomäki R. Intravenous drug dependence in adolescence. J Subst Abuse. 2005 Jan 1;10(5):315–326. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juutinen J., Hakko H., Meyer-Rochow V.B., Räsänen P., Timonen M., Study-70 Research Group Body mass index (BMI) of drug-naïve psychotic adolescents based on a population of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Psychiatry. 2008 Oct 1;23(7):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keeshin B.R., Luebbe A.M., Strawn J.R., Saldaña S.N., Wehry A.M., DelBello M.P. Sexual abuse is associated with obese children and adolescents admitted for psychiatric hospitalization. J Pediatr. 2013 Jul 1;163(1):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan R.A., Mican L.M., Suehs B.T. Effects of olanzapine and risperidone on metabolic factors in children and adolescents: a retrospective evaluation. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009 Jul 1;15(4):320–328. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000358319.81307.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laakso E., Hakko H., Räsänen P., Riala K., STUDY T. Suicidality and unhealthy weight control behaviors among female underaged psychiatric inpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 2013 Feb 1;54(2):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le L., Bostwick J.R., Andreasen A., Malas N. Neuroleptic prescribing and monitoring practices in pediatric inpatient medical and psychiatric settings. Hosp Pediatr. 2018 Jul 1;8(7):410–418. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2017-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mäkikyrö T.H., Hakko H.H., Timonen M.J., Lappalainen J.A., Ilomäki R.S., Marttunen M.J. Smoking and suicidality among adolescent psychiatric patients. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Mar 1;34(3):250–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin A., Landau J., Leebens P., Ulizio K., Cicchetti D., Scahill L. Risperidone-associated weight gain in children and adolescents: a retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2000;10(4):259–268. doi: 10.1089/cap.2000.10.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]