Abstract

Objectives:

Although dramatic responses to MET inhibitors have been reported in patients with MET exon 14 (METex14) mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the impact of these treatments on overall survival in this population is unknown.

Methods:

We conducted a multicenter retrospective analysis of patients with METex14 NSCLC to determine if treatment with MET inhibitors impacts median overall survival (mOS). Event-time distributions were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox models were fitted to estimate hazard ratios.

Results:

We identified 148 patients with METex14 NSCLC; the median age was 72; 57% were women and 39% were never smokers. Of the 34 metastatic patients who never received a MET inhibitor, the mOS was 8.1 months; those in this group with concurrent MET amplification had a trend toward worse survival compared to cancers without MET amplification (5.2 months vs 10.5 months, P = 0.06). Of the 27 metastatic patients who received at least one MET inhibitor the mOS was 24.6 months. A model adjusting for receipt of a MET inhibitor as first- or second-line therapy as a time-dependent covariate demonstrated that treatment with a MET inhibitor was associated with a significant prolongation in survival (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.92, P = 0.04) compared to patients who did not receive any MET inhibitor. Among 22 patients treated with crizotinib, the median progression-free survival was 7.4 months.

Discussion:

For patients with METex14 NSCLC, treatment with a MET inhibitor is associated with an improvement in overall survival.

Keywords: NSCLC, MET exon 14, TKI, overall survival

1. INTRODUCTION

The identification of targetable genomic mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has transformed the treatment approach for cancers harboring alterations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), ROS1, and BRAF.[1–8] Mutations in MET exon 14 (METex14) or its flanking introns have recently been identified as a distinct molecular subtype of lung cancer, occurring in approximately 3% of NSCLCs,[9–11] and several recent reports have demonstrated that these cancers can respond to treatment with MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).[9–19] However, whether treatment with a MET TKI in METex14 mutant NSCLC improves survival for patients is currently unknown.

Demonstrating an overall survival (OS) benefit from MET TKIs in this population through a prospective, randomized clinical trial may be difficult for several reasons. As in the case with EGFR- and ALK-mutant lung cancers, most clinical trials comparing targeted therapy to standard chemotherapy have failed to show an OS benefit,[1–5] largely due to patient crossover from one treatment arm to the other or because of availability of other approved or investigational agents administered after disease progression. Furthermore, many patients are currently being treated with off-label crizotinib, a potent MET inhibitor, outside the setting of a clinical trial, which could hamper recruitment of patients to randomized studies comparing a MET TKI to standard chemotherapy in the METex14 NSCLC population.

Given these challenges, one approach for demonstrating a survival advantage with a targeted therapy is to retrospectively compare patients with a specific mutational subtype of lung cancer who either did or did not receive treatment with a targeted therapy. In ALK-rearranged NSCLC, for example, this type of analysis was used to demonstrate that treatment with crizotinib was associated with a survival benefit compared to patients who had never received a TKI.[20] Therefore, in order to determine whether MET TKIs impact clinical outcomes of METex14 mutant NSCLC, we conducted an analysis comparing the overall survival of patients who received a MET TKI to a retrospectively-identified cohort of patients who never received any MET TKIs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population and procedures

Clinical, pathologic, and genomic data were collected from patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC who had also consented to local institutional review board-approved protocols that allowed for the analysis of these data through December 1, 2016, from 12 academic institutions. Testing for METex14 mutations was determined either through local or commercial sequencing assays according to institutional practices. MET genomic amplification was determined through local institutional assessment, either through next generation sequencing (NGS)[10] or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).[21] For the survival analysis, patients were included if they were diagnosed with advanced NSCLC on or after January 1, 2010. Patients were considered to be treated with a MET TKI if they received at least one of the following: crizotinib, glesatinib, capmatinib, savolitinib, tepotinib, cabozantinib, or merestinib. For patients enrolled in a MET TKI clinical trial, permission was granted from the sponsor to include overall survival data in this study.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The progression-free survival (PFS) analysis was determined from the start date of TKI treatment until the date of clinical or radiographic progression or death, as assessed by each principal investigator. Patients who were alive without disease progression were censored on the date of their last adequate disease assessment. OS was determined from date of diagnosis of stage IV disease until death due to any cause. Patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored on the last date of contact. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate event-time distributions, and the Greenwood formula was used to estimate the standard errors of the estimates. Log-rank tests were used to test for differences in event-time distributions, and Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to obtain estimates of hazard ratios in univariate and in multivariable models. Because patients were treated with a MET inhibitor at varying timepoints in their disease, a Cox proportional hazards model that adjusted for therapy as a time-varying covariate was fitted to appropriately estimate the effect of MET TKI therapy on outcome. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the associations between categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous measures between groups. The t-test was used to compare differences in age at diagnosis between patients who received a MET inhibitor and patients who did not. All p-values are two-sided and confidence intervals are at the 95% level.

3. RESULTS

The clinicopathologic characteristics from a total of 148 patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC are shown in supplementary Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 72 (range: 43–88, age distribution shown in supplementary Figure 1), 57% of patients were women, 39% were never smokers and of those who were current or former smokers, 71% had a ≥10 pack-year history of tobacco use. The most prevalent histology was adenocarcinoma (77%), followed by pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma (also called pleomorphic carcinoma) (14%), squamous (5%), adenosquamous (3%) and poorly differentiated carcinoma (1%). At the time of initial diagnosis, 36% of patients had stage I disease, 12% had stage II, 22% had stage III, and 30% had stage IV. Of the 71 patients who had or developed stage IV disease, the most common sites of metastases were lymph nodes (67%) and lung (53%), followed by pleural/pericardial metastases or malignant effusions (51%), bone (49%), and brain (37%) (supplementary Table 2). The genomic alteration leading to MET exon 14 skipping was a point mutation in 84 patients (61%), a deletion in 50 patients (36%), an insertion in one patient (0.7%), and two patients (2%) had an amino acid substitution at tyrosine 1003 which is not predicted to result in MET exon 14 skipping but instead abrogates binding of the CBL E3 ubiquitin ligase. In 11 cases the precise MET genomic alteration was not available. MET was concurrently amplified in 21% of cases in which amplification status was documented; MET copy number was not assessed in roughly one-third of cases (supplementary Table 1).

Among the 71 patients who had or developed stage IV disease, ten patients were lost to follow up after their initial workup because they received care at other facilities, and therefore 61 patients met inclusion criteria for the survival analysis. Among these 61 patients, 34 never received treatment with a MET TKI and 27 patients received treatment with at least one MET TKI (Figure 1). Between these two groups, there was no significant difference in clinicopathologic characteristics including age at diagnosis (P=0.85), sex (P=0.43), smoking status (P=0.79), histology (P=0.77), presence of brain metastases (P=1.00), the presence of concurrent MET amplification (P=0.10) (Table 1), and the distribution of year of diagnosis (P=0.95).

Figure 1:

Study population

Table 1:

Clinicopathologic and genomic characteristics of the 61 patients with stage IV METex14 mutant NSCLC included in the survival analysis

| Characteristic | Overall cohort (N = 61) | Patients who received treatment with a MET TKI (N = 27) | Patients who never received treatment with a MET TKI (N = 34) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (range) | 70 (43–87) | 67 (53–87) | 70 (43–86) | 0.85 |

| Sex | 0.43 | |||

| Male | 27 (44) | 10 (37) | 17 (50) | |

| Female | 34 (56) | 17 (63) | 17 (50) | |

| Smoking history | 0.79a | |||

| Never smoker | 25 (41) | 12 (44) | 13 (38) | |

| Smoker | 36 (59) | 15 (57) | 21 (62) | |

| < 10 pack-yearsb | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| ≥ 10 pack-years | 25 | 10 | 15 | |

| Smoker, pack-years unknown | 1 | - | 1 | |

| Histology | 0.77c | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 45 (74) | 19 (70) | 26 (76) | |

| Non-adenocarcinoma | 16 (26) | 8 (30) | 8 (24) | |

| Sarcomatoid/ Pleomorphic | 7 | 2 | 5 | |

| Squamous | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 2 | - | 2 | |

| Adenosquamous | 1 | 1 | - | |

| Brain metastases at diagnosis | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 19 (39) | 9 (41) | 10 (37) | |

| No | 30 (61) | 13 (59) | 17 (63) | |

| Unknown | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| METex14 mutation with concurrent MET amplification | 0.10 | |||

| Yes | 14 (33) | 8 (50) | 6 (23) | |

| No | 28 (67) | 8 (50) | 20 (77) | |

| Unknown | 19 | 11 | 8 |

Data are reported as n (%); percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding

Never smokers vs smokers

Pack-years are calculated for both current and former smokers combined

Adenocarcinoma histology vs non-adenocarcinoma histology

TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

From the time of stage IV diagnosis, the median overall survival (mOS) among the 34 patients who never received a MET TKI was 8.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 5.3 months – not reached [NR]; Figure 2A). Within this group, MET amplification status was known in 26 patients (six patients [23%] had concurrent MET amplification while 20 patients [77%] were not amplified), and patients with METex14 mutant cancers and concurrent MET genomic amplification showed a trend toward worse mOS compared to cancers without concurrent MET amplification (5.2 months vs 10.5 months, P=0.06; Figure 2B). Moreover, no difference in overall survival was found in the same group of patients according to adenocarcinoma vs non-adenocarcinoma histology (P= 0.69; supplementary Figure 2) and smoking history (never smokers vs smokers, P= 0.95; supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Overall survival of patients with METex14 mutant stage IV NSCLC who did or did not receive treatment with a MET TKI.

(A) Overall survival of 34 patients with stage IV METex14 NSCLC who never received a MET TKI. (B) Overall survival of stage IV METex14 NSCLC who never received a MET TKI and with known MET amplification status: 20 patients had no concurrent MET amplification (black line), six patients had concurrent MET amplification (red line). (C) Overall survival of 27 patients with stage IV METex14 NSCLC who received treatment with at least one MET TKI. CI: confidence interval. NR: not reached.

Of the 27 patients who were treated with a MET TKI, 23 patients received only one MET TKI and four patients received two MET TKIs as different lines of therapy. The MET TKI administered included crizotinib in 24 patients (20 were treated with commercial crizotinib, four were enrolled in a clinical trial [NCT00585195]), glesatinib in four patients (NCT00679133), and capmatinib in three patients (NCT02414139). The mOS in patients who received at least one MET TKI was 24.6 months (95% CI 12.1 months – NR; Figure 2C). Among the subset of 20 patients who only received crizotinib and no other MET TKI, mOS was not reached (95% CI 9.5-NR; supplementary Figure 4).

Among 23 patients who received only one MET TKI over the course of therapy, 12 (44%) received the MET TKI as first-line therapy, ten (37%) as second-line, two (7%) as third-line, one (4%) as fourth-line, and two (7%) as fifth-line; four patients were treated with more than one MET TKI (Table 2). In order to account for the possibility that patients who were treated with a MET TKI as a later line of therapy might have more indolent disease which might be associated with a survival benefit independent of treatment with a MET TKI, we fitted a model adjusting for receipt of a MET TKI as first- or second-line therapy as a time-dependent covariate; after adjusting for non-adenocarcinoma histology (HR 2.84, P=0.098) and MET amplification (HR 3.26, P=0.039), we found that treatment with a MET TKI was associated with a significant prolongation in overall survival among patients with stage IV METex14 mutant NSCLC (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.92, P=0.04) when compared to those who did not receive a MET TKI.

Table 2:

Treatment history of patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC included in the survival analysis cohort.

| Characteristics | Patients who received treatment with a MET TKI (N = 27) | Patients who never received treatment with a MET TKI (N = 34)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lines of treatment | <0.001 | ||

| 0 lines | 0 (0) | 9 (27) | |

| 1 lines | 10 (37) | 19 (58) | |

| 2 lines | 6 (22) | 3 (9) | |

| 3 lines | 4 (15) | 2 (6) | |

| 4 lines | 5 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 lines | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | |

| Platinum-based regimen | 0.30 | ||

| Yes | 13 (48) | 21 (64) | |

| No | 14 (52) | 12 (36) | |

| Pemetrexed-based regimen | 0.30 | ||

| Yes | 12 (44) | 20 (61) | |

| No | 15 (56) | 13 (39) | |

| Treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 10 (37) | 3 (9) | |

| No | 17 (63) | 30 (91) | |

| Line of treatment when MET inhibitor was administered | |||

| 1st lineb | 12 (44) | - | |

| 2nd linec | 10 (37) | - | |

| 3rd line only | 2 (7) | - | |

| 4th line only | 1 (4) | - | |

| 5th line only | 2 (7) | - |

Data are reported as n (%); percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding

For one patient the type of systemic therapy received was not available

One patient who received 1st line crizotinib also received 4th line glesatinib

One patient who received 2nd line glesatinib also received 3rd line crizotinib; one patient who received 2nd line capmatinib also received 3rd line crizotinib; one patient who received 2nd line crizotinib also received 4th line glesatinib

TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

We also analyzed whether there were other treatment differences between the MET TKI treated vs. untreated patients with metastatic METex14 mutant NSCLC (Table 2). We found that the majority of patients who received a MET TKI received either one or two lines of treatment (37% and 22%, respectively, range 1–5) while the majority of patients who never received a MET inhibitor received one line of treatment (58%, range 0–3). Overall, the cohort of patients who received a MET TKI received more lines of therapy than the patients who never received any MET TKI (P<0.001). There was no significant difference between the two groups in receipt of platinum-doublet chemotherapy (P= 0.30) or pemetrexed-based chemotherapy (P= 0.30) (Table 2).

Since METex14 mutations have only been detected through routine next generation sequencing platforms more recently and around the same time as the approval of PD-1 inhibitors for NSCLC, we not surprisingly found that patients who received treatment with a MET TKI were also more likely to have received treatment with a PD-1 inhibitor compared to patients who never received a MET inhibitor (37% vs. 9%, P= 0.01). However, among the 10 MET TKI-treated patients who also received a PD-1 inhibitor, the best objective response to the PD-1 therapy was progressive disease in eight patients, one patient had stable disease, and one was not evaluable. Among the three MET TKI-untreated patients who also received a PD-1 inhibitor, the best objective response in two patients was progressive disease, and one patient experience a partial response. Therefore, it did not appear that treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors in the MET TKI-treated group was likely to have had a significant impact on overall survival compared to patients who never received a MET TKI.

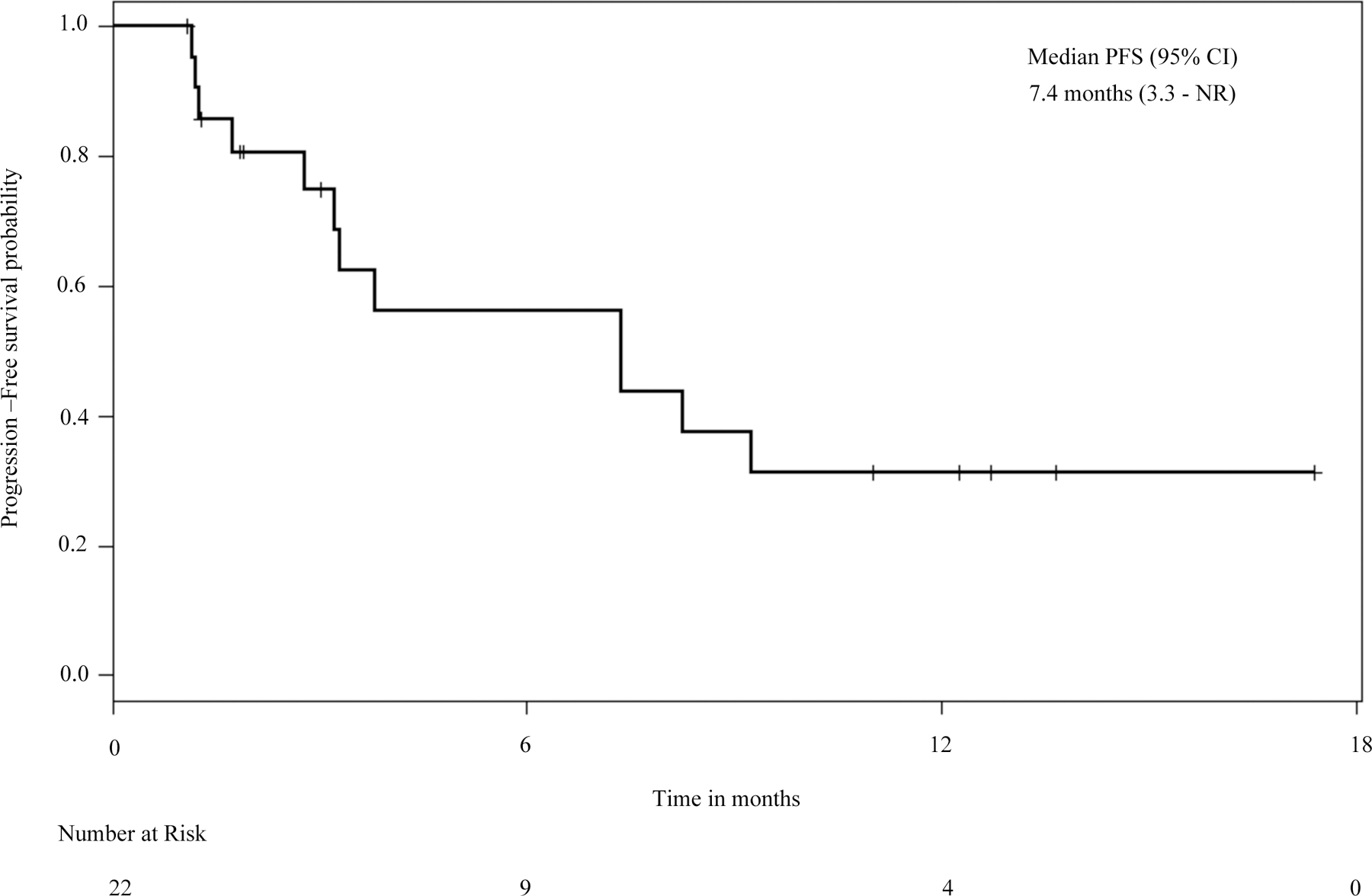

The most frequent MET TKI used in the MET TKI-treated cohort was crizotinib in 24 of 27 patients (89%). While several cases of crizotinib response among patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC have been reported,[9–17] the length of time that most patients benefit from crizotinib is not yet known. Among the patients in our cohort treated with crizotinib as their first MET TKI, the median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 7.4 months (95% CI 3.3 months – NR; Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Progression-free survival on crizotinib in patients with METex14 mutant stage IV NSCLC.

Progression free survival curve of 22 patients with stage IV METex14 NSCLC who received crizotinib as their first MET TKI (any line of treatment). CI: confidence interval. NR: not reached.

4. DISCUSSION

As lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide,[22] identifying life-prolonging therapies for this disease is of paramount importance. While there have been several case reports of responses to MET TKIs among patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC,[9–17] whether these agents extend survival in this population is currently unknown. Answering this question prospectively through randomized phase 3 clinical trials will be challenging for several reasons. Given the widespread availability of crizotinib, randomized trials comparing a MET TKI to chemotherapy may be hampered due to slow patient accrual. Furthermore, planned or unplanned patient crossover from a non-targeted therapy to a MET TKI is likely to confound detection of a discernable survival benefit attributable to the MET TKI, as has been observed in randomized trials for NSCLC patients with EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangements.[1–5]

Therefore, to determine if treatment with a MET TKI confers a survival benefit in patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC, we conducted a retrospective analysis using data from 12 institutions. As described in earlier studies,[9–11] we found that METex14 mutations were common both in metastatic and early-stage NSCLC. Given the high prevalence of MET exon 14 mutations in stage I-III NSCLC, additional studies are needed to determine the recurrence risk in these patients, and prospective, randomized clinical trials exploring the use of adjuvant MET TKI in patients with early stage METex14 mutant NSCLC should be considered.

In our cohort, the median overall survival for patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC who never received a MET TKI was only 8.1 months. We observed a non-significant trend toward worse survival in cases with concurrent MET genomic amplification. However, institutional and methodologic differences in defining MET amplification, along with intratumoral heterogeneity in MET gene copy number, may impede accurate determination of MET amplification status.[21, 23] Overall survival was significantly improved among patients in our cohort with METex14 mutant NSCLC who were treated with a MET TKI.

There are several inherent limitations to conducting a retrospective survival analysis. Reasons that some patients never received treatment with a MET inhibitor varied and included lack of recognition of an actionable genomic alteration until after the patient’s death, inability of patients to gain access to MET TKIs, or declining performance status by the time the MET exon 14 mutation was identified; some of these factors may have been independently conferred a poor prognosis and impacted survival in this population (such as poor performance status). Furthermore, our cohort of patients who received a MET TKI included several clinical trial patients, who may have a better performance status or more indolent disease compared to patients who do not participate in clinical trials. However, of the patients in our cohort who received a MET TKI, a significant fraction of patients (20 of 27, 74%) were treated with commercially-available, off-label crizotinib, rather than on a clinical trial. The median PFS of patients treated with crizotinib as their first MET TKI in our cohort was comparable to the median PFS of a recently presented clinical trial of crizotinib in MET exon 14 mutant NSCLC, indicating that the population included in our retrospective analysis behaved similarly to clinical trial patients.[24] Although most patients in our study received crizotinib, a subset of them were treated with glesatinib or capmatinib, so it is unclear if each of these agents might independently be associated with a survival benefit.

Many of the clinicopathologic features were similar between the MET TKI-treated vs. untreated patients, and these two groups were balanced in terms of year of diagnosis with stage IV disease, as well as exposure to platinum-doublet chemotherapy and pemetrexed-based chemotherapy. However, 27% of those who never received a MET TKI also never received any systemic treatment for their disease, possibly because the advanced age of this population was felt to be a barrier to treatment with platinum doublet chemotherapy. While this highlights the need to treat these patients with more tolerable targeted therapies, the imbalance in the number of lines of therapy between the TKI-treated and TKI-naïve groups (Table 2) could suggest bias in terms of either increased aggressiveness of disease or decreased overall fitness among the TKI-naïve group which could also have influenced the survival results. Patients treated with a MET TKI also received more lines of therapy in total, including treatment with a PD-1 pathway inhibitor. While treatment with immunotherapy did not appear to be particularly effective in this molecular subtype of NSCLC, larger cohorts of patients are needed to determine the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibition in METex14 mutant NSCLC.

Due to the poor prognosis of patients with METex14 mutant NSCLC who never receive MET TKI, testing for METex14 mutations should be performed at diagnosis among patients with advanced NSCLC, particularly in cancers lacking activating mutations in KRAS, EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and BRAF, as these genomic alterations appear to be mutually exclusive from one another.[9, 10] If supported by prospective data on earlier efficacy endpoints, the survival data presented here should support the widespread, early use of MET TKI in the treatment of patients with metastatic METex14 mutant NSCLC, especially in light of the generally favorable side effect profile associated with these agents.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

The impact of MET inhibition on survival in MET exon 14 mutant NSCLC is unclear

Use of a MET inhibitor in METex14 NSCLC is associated with improved survival

The median progression-free survival to crizotinib in METex14 NSCLC was 7.4 months

Funding:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest Statement

Dr. Awad reports personal fees from AbbVie, Ariad, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Nektar, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, outside the submitted work. Dr. Dahlberg reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work. Dr. Drilon reports honoraria from Ignyta, LOXO Oncology, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Ariad, and from TP Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. Noonan is employed by Merck. Dr. Ou reports personal fees from Pfizer, Novartis, and Ignyta, outside the submitted work. Dr. Costa reports personal fees from Pfizer, Ariad, and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Dr. Gadgeel reports personal fees from Novartis and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Steuer reports personal fees from EMD Serono, outside the submitted work. Dr. Forde has received research funding from Novartis and served as consultant to Novartis. Dr. Janne reports personal fees from Pfizer, during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca; personal fees from Boehringher Ingelheim, Roche/Genetech, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Ignyta, LOXO Oncology, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly and company, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from PUMA, grants from Astellas, outside the submitted work. Dr. Mok reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, Eli Lilly, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, MSD, Pfizer, Clovis Oncology, Taiho, and SFJ Pharmaceuticals; personal fees from Merck Serono, Vertex, ACEA Biosciences, geneDecode, Oncogenex, Celgene, Ignyta Inc; grants from Eisai; other from Samomics Ltd. and from Cirina, outside the submitted work. Dr. Sholl reports personal fees from Genentech, personal fees from Research to Practice, outside the submitted work. Dr. Heist reports grants from Novartis, Abbvie, Millenium, Genentech Roche, Incyte, Mirati, Celgene, Debiopharm, other from Boehringer Ingelheim, other from Ariad, outside the submitted work. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, Sunpaweravong P, Han B, Margono B, Ichinose Y, Nishiwaki Y, Ohe Y, Yang JJ, Chewaskulyong B, Jiang H, Duffield EL, Watkins CL, Armour AA, Fukuoka M, Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma, The New England journal of medicine 361(10) (2009) 947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou S, Ren S, Lu S, Zhang L, Hu C, Hu C, Luo Y, Chen L, Ye M, Huang J, Zhi X, Zhang Y, Xiu Q, Ma J, Zhang L, You C, Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study, Lancet Oncol 12(8) (2011) 735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, Geater SL, Orlov S, Tsai CM, Boyer M, Su WC, Bennouna J, Kato T, Gorbunova V, Lee KH, Shah R, Massey D, Zazulina V, Shahidi M, Schuler M, Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations, J Clin Oncol 31(27) (2013) 3327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, Felip E, Cappuzzo F, Paolini J, Usari T, Iyer S, Reisman A, Wilner KD, Tursi J, Blackhall F, Investigators P, First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer, The New England journal of medicine 371(23) (2014) 2167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Palmero R, Garcia-Gomez R, Pallares C, Sanchez JM, Porta R, Cobo M, Garrido P, Longo F, Moran T, Insa A, De Marinis F, Corre R, Bover I, Illiano A, Dansin E, de Castro J, Milella M, Reguart N, Altavilla G, Jimenez U, Provencio M, Moreno MA, Terrasa J, Munoz-Langa J, Valdivia J, Isla D, Domine M, Molinier O, Mazieres J, Baize N, Garcia-Campelo R, Robinet G, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Lopez-Vivanco G, Gebbia V, Ferrera-Delgado L, Bombaron P, Bernabe R, Bearz A, Artal A, Cortesi E, Rolfo C, Sanchez-Ronco M, Drozdowskyj A, Queralt C, de Aguirre I, Ramirez JL, Sanchez JJ, Molina MA, Taron M, Paz-Ares L, Spanish P-C Lung Cancer Group in collaboration with Groupe Francais de, T. Associazione Italiana Oncologia, Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial, Lancet Oncol 13(3) (2012) 239–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shaw AT, Ou SH, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Solomon BJ, Salgia R, Riely GJ, Varella-Garcia M, Shapiro GI, Costa DB, Doebele RC, Le LP, Zheng Z, Tan W, Stephenson P, Shreeve SM, Tye LM, Christensen JG, Wilner KD, Clark JW, Iafrate AJ, Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer, The New England journal of medicine 371(21) (2014) 1963–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJ, Souquet PJ, Quoix E, Baik CS, Barlesi F, Kim TM, Mazieres J, Novello S, Rigas JR, Upalawanna A, D’Amelio AM Jr., Zhang P, Mookerjee B, Johnson BE, Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously treated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: an open-label, multicentre phase 2 trial, Lancet Oncol 17(7) (2016) 984–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA, Aronson SL, Su PF, Shyr Y, Camidge DR, Sequist LV, Glisson BS, Khuri FR, Garon EB, Pao W, Rudin C, Schiller J, Haura EB, Socinski M, Shirai K, Chen H, Giaccone G, Ladanyi M, Kugler K, Minna JD, Bunn PA, Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs, JAMA 311(19) (2014) 1998–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, Chmielecki J, Lu X, Bauer TM, Akimov M, Bufill JA, Lee C, Jentz D, Hoover R, Ou SH, Salgia R, Brennan T, Chalmers ZR, Jaeger S, Huang A, Elvin JA, Erlich R, Fichtenholtz A, Gowen KA, Greenbowe J, Johnson A, Khaira D, McMahon C, Sanford EM, Roels S, White J, Greshock J, Schlegel R, Lipson D, Yelensky R, Morosini D, Ross JS, Collisson E, Peters M, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors, Cancer Discov 5(8) (2015) 850–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Patnaik A, Powell SF, Gentzler RD, Martins RG, Stevenson JP, Jalal SI, Panwalkar A, Yang JC, Gubens M, Sequist LV, Awad MM, Fiore J, Ge Y, Raftopoulos H, Gandhi L, K.-. investigators, Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study, Lancet Oncol 17(11) (2016) 1497–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schrock AB, Frampton GM, Suh J, Chalmers ZR, Rosenzweig M, Erlich RL, Halmos B, Goldman J, Forde P, Leuenberger K, Peled N, Kalemkerian GP, Ross JS, Stephens PJ, Miller VA, Ali SM, Ou SH, Characterization of 298 Patients with Lung Cancer Harboring MET Exon 14 Skipping Alterations, J Thorac Oncol 11(9) (2016) 1493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jenkins RW, Oxnard GR, Elkin S, Sullivan EK, Carter JL, Barbie DA, Response to Crizotinib in a Patient With Lung Adenocarcinoma Harboring a MET Splice Site Mutation, Clin Lung Cancer 16(5) (2015) e101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Waqar SN, Morgensztern D, Sehn J, MET Mutation Associated with Responsiveness to Crizotinib, J Thorac Oncol 10(5) (2015) e29–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mendenhall MA, Goldman JW, MET-Mutated NSCLC with Major Response to Crizotinib, J Thorac Oncol 10(5) (2015) e33–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Paik PK, Drilon A, Fan PD, Yu H, Rekhtman N, Ginsberg MS, Borsu L, Schultz N, Berger MF, Rudin CM, Ladanyi M, Response to MET inhibitors in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET mutations causing exon 14 skipping, Cancer Discov 5(8) (2015) 842–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dong HJ, Li P, Wu CL, Zhou XY, Lu HJ, Zhou T, Response and acquired resistance to crizotinib in Chinese patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET Exon 14 splicing alternations, Lung Cancer 102 (2016) 118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ou SI, Young L, Schrock AB, Johnson A, Klempner SJ, Zhu VW, Miller VA, Ali SM, Emergence of Preexisting MET Y1230C Mutation as a Resistance Mechanism to Crizotinib in NSCLC with MET Exon 14 Skipping, J Thorac Oncol 12(1) (2017) 137–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shea M, Huberman MS, Costa DB, Lazarus-Type Response to Crizotinib in a Patient with Poor Performance Status and Advanced MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutation-Positive Lung Adenocarcinoma, J Thorac Oncol 11(7) (2016) e81–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jorge SE, Schulman S, Freed JA, VanderLaan PA, Rangachari D, Kobayashi SS, Huberman MS, Costa DB, Responses to the multitargeted MET/ALK/ROS1 inhibitor crizotinib and co-occurring mutations in lung adenocarcinomas with MET amplification or MET exon 14 skipping mutation, Lung Cancer 90(3) (2015) 369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Solomon BJ, Riely GJ, Gainor J, Engelman JA, Shapiro GI, Costa DB, Ou SH, Butaney M, Salgia R, Maki RG, Varella-Garcia M, Doebele RC, Bang YJ, Kulig K, Selaru P, Tang Y, Wilner KD, Kwak EL, Clark JW, Iafrate AJ, Camidge DR, Effect of crizotinib on overall survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring ALK gene rearrangement: a retrospective analysis, Lancet Oncol 12(11) (2011) 1004–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Noonan SA, Berry L, Lu X, Gao D, Baron AE, Chesnut P, Sheren J, Aisner DL, Merrick D, Doebele RC, Varella-Garcia M, Camidge DR, Identifying the Appropriate FISH Criteria for Defining MET Copy Number-Driven Lung Adenocarcinoma through Oncogene Overlap Analysis, J Thorac Oncol 11(8) (2016) 1293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ferlay JSI, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Maters C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr. (Accessed 28 February 2017). [Google Scholar]

- [23].Casadevall D, Gimeno J, Clave S, Taus A, Pijuan L, Arumi M, Lorenzo M, Menendez S, Canadas I, Albanell J, Serrano S, Espinet B, Salido M, Arriola E, MET expression and copy number heterogeneity in nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer (nsNSCLC), Oncotarget 6(18) (2015) 16215–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Drilon A, Clark J, Weiss J, Ou S, Camidge DR, Solomon B, Otterson G, Villaruz L, Riely G, Heist R, Shapiro G, Murphy D, Wang S, Usari T, Li S, Wilner K, Paik P, Updated antitumor activity of crizotinib in patients with MET exon 14-altered advanced non-small cell lung cancer, J Thorac Oncol 13(10) (2018) S348. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.