Abstract

Introduction.

Macrophages are capable of extreme plasticity and their activation state has been strongly associated with solid tumor growth progression and regression. Although the macrophage response to extracellular matrix (ECM) isolated from normal tissue is reasonably well understood, there is a relative dearth of information regarding their response to ECM isolated from chronically inflamed tissues, pre-neoplastic tissues, and neoplastic tissues. Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a type of neoplasia driven by chronic inflammation in the distal esophagus, and the length of the esophagus provides the opportunity to investigate macrophage behavior in the presence of ECM isolated from a range of disease states within the same organ.

Methods.

Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM hydrogels were prepared from decellularized EAC tissue. The hydrogels were evaluated for their nanofibrous structure (SEM), biochemical profile (targeted and global proteomics), and direct effect upon macrophage (THP-1 cell) activation state (qPCR, ELISA, immunolabeling) and indirect effect upon epithelial cell (Het-1A) migration (Boyden chamber).

Results.

Nanofibrous ECM hydrogels from the three tissue types could be formed, and normal and neoplastic ECM showed distinctive protein profiles by targeted and global mass spectroscopy. ECM proteins functionally related to cancer and tumorigenesis were identified in the neoplastic esophageal ECM including collagen alpha-1(VIII) chain (COL8A1), lumican, and elastin. Metaplastic and neoplastic esophageal ECM induce distinctive effects upon THP-1 macrophage signaling compared to normal esophageal ECM. These effects include activation of pro-inflammatory IFNγ and TNFα gene expression and anti-inflammatory IL1RN gene expression. Most notably, neoplastic ECM robustly increased macrophage TNFα protein expression. The secretome of macrophages pre-treated with metaplastic and neoplastic ECM increases the migration of normal esophageal epithelial cells, similar behavior to that shown by tumor cells. Metaplastic ECM shows similar but less pronounced effects than neoplastic ECM suggesting the abnormal signals also exist within the pre-cancerous state.

Conclusion.

A progressively diseased ECM, as exists within the esophagus exposed to chronic gastric reflux, can provide insights into novel biomarkers of early disease and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Macrophage, extracellular matrix, decellularization, esophageal adenocarcinoma, metaplasia, gastroesophageal reflux

Graphical Abstract:

1. Introduction

The plasticity and diverse functions of macrophages are well-documented (1). Macrophage expression of pro-inflammatory mediators (“M1” activation) versus wound repair mediators or tumor tolerance mediators (“M2” activation), and the associated cellular pathways, are modulated in part by signals present within the tissue microenvironment (2–4). The microenvironment, in turn, is represented in large part by the extracellular matrix (ECM) (5).

The ECM represents the composite assembly of structural and functional molecules secreted by the resident cells of each tissue and organ (6). The secreted matrix is gradually but continually replaced during health; i.e., homeostasis. In contrast, the ECM changes rapidly during states of inflammation and neoplasia (7–9). The ECM of neoplastic tissues differs markedly from that of normal tissue with respect to composition (5, 7, 8, 10) and mechanical properties (11). Components of the ECM such as hyaluronic acid (12, 13), collagen degradation products (14), matricellular proteins (15) and matrix-bound nanovesicles (16, 17) can affect macrophage phenotype and the associated downstream effects upon tissue structure and function.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) is a chronic inflammatory-driven cancer. However, despite the reasonably well-established reflux-induced inflammation to metaplasia to neoplasia pathogenesis (18), there is a limited understanding of the associated changes within the ECM during disease progression. It has recently been shown that ECM harvested from normal esophageal tissue can markedly downregulate intracellular pathways associated with cancer in pre-neoplastic and neoplastic esophageal cell lines (19). Since macrophages play an essential role in both homeostatic and pathologic processes, and because immunomodulatory strategies are being investigated for potential therapeutic applications (20, 21), the effect of ECM derived from tissues in various states of health and disease upon macrophage activation state is of interest and importance. The present study investigated the effect of ECM harvested from normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic esophageal tissue upon the activation state of macrophages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ECM hydrogel preparation

All animal procedures were approved by the Allegheny Health Network Research Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #992). Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic tissue was harvested from rats subjected to the Levrat surgical procedure to induce EAC (22). Briefly, the jejunum of Sprague-Dawley rats was anastomosed to the distal esophagus, creating constant acid reflux and chronic inflammation in the distal esophagus. Over a period of 17–33 weeks, normal esophageal squamous epithelium transforms to metaplastic Barrett’s esophagus (i.e., intestinal metaplasia) and then to a neoplastic, glandular cell type (EAC). The progression of changes in cell phenotype in the rat model mimics the pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Esophagi were explanted, opened longitudinally and frozen on edge in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) using liquid nitrogen. Full-thickness tissue sections of the length of each esophagus were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to confirm the presence of the three different disease regions, and the normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic esophageal tissues were isolated. The three tissue types were separately decellularized using a protocol modified from Sutherland et al. (23). Briefly, the tissue was soaked in distilled water at −80°C overnight, and subsequently agitated for 1 h with distilled water, rocked at 37°C for 1 h in 0.25% trypsin/0.05% EDTA, stirred for 4 hrs in 4% sodium deoxycholate, and rocked at 37°C for 2 hrs in 1 M NaCl + 50 U/mL DNAse, repeated 3 times. The tissue was then agitated for 1 h with distilled water, disinfected with 0.1% PAA in 4% ethanol at 300 rpm for 2 hrs, and rinsed in alternating 1x PBS and distilled water 4 times, 15 min each shaking at 300 rpm. The resulting ECM was lyophilized. ECM hydrogels were prepared from the normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM as previously described (24). Briefly, the ECM was powdered, digested by pepsin for 48 hours in 0.01 M HCl, and neutralized (temperature-controlled, pH 7.4) to produce normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM hydrogels.

The same decellularization protocol was used for human tissues. De-identified human tissues were provided under approved collaboration agreements between the University of Pittsburgh and West Penn Allegheny Hospital System (I#0040039), and between University of Pittsburgh and Fundación Favaloro (I#0044782). Table 1 shows the procedures and assays conducted with the two different species sources of ECM. The limited quantity of rat and human samples available prevented complete duplication of all assays and procedures between the two species; however each experiment was performed to appropriate statistical rigor, with n=3–5 and n=2 for qualitative experiments (SEM, SDS-PAGE).

Table 1. ECM sources for experiments.

The procedures and assays conducted with the rat and human ECM sources are listed.

| Rat (Levrat) | Human | |

|---|---|---|

| Decellularization efficacy (H&E, DAPI stain) | √ | √ |

| Gel ultrastructure (SEM) | √ | |

| SDS-PAGE | √ | |

| Absolute proteomic quantification | √ | |

| Macrophage (gene expression, protein expression, immunolabeling) | √ | √ |

| Migration of normal esophageal epithelial cells | √ |

ECM isolated from porcine urinary bladder (UBM) was included as a heterologous ECM control. UBM has been well characterized as a biomaterial that promotes macrophage activation toward an M2-like phenotype, and was prepared as previously described (24) to be included in the experiments evaluating the effect of ECM upon cell function e.g., macrophage and epithelial cell experiments.

2.1.1. Decellularization Efficacy

Crapo et al. (25) recommended the following criteria for decellularization: 1) less than 50 ng dsDNA per mg ECM dry weight, 2) less than 200 bp DNA fragment length, and 3) lack of visible nuclear material in the tissue sections stained with 4’6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) or H&E. Only the third criteria was used in the present study on rat and human ECM to determine decellularization efficacy, because of limited amounts of available material. A subset of the decellularized and lyophilized ECM materials (n=3) was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h. The fixed samples were paraffin embedded and 5 µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or 40 ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to identify any remaining cellular structures.

2.2. ECM hydrogel characterization

2.2.1. ECM hydrogel ultrastructure

ECM hydrogels (6 mg/mL) were prepared from the rat normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM. ECM hydrogel ultrastructure was examined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) as previously described (26). Samples were fixed in cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 24 hours, rinsed in PBS, dehydrated with graded ethanol (30, 50, 70, 90, 100% ethanol in PBS) at 45 min per wash, and critical point dried for 5 hours (Leica EM CPD030 Critical Point Dryer, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). After drying, gels were sputter-coated (Sputter Coater 108 Auto, Cressington Scientific Instruments, Watford, UK) with a 4.6 nm thick gold/palladium alloy coating and imaged with a scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM6330f, JEOL Ltd., Peabody, MA) at 2,000 and 10,000x magnification (n=2, 5 technical replicates).

2.2.2. Solubilized ECM chromatographic profile

The solubilized rat normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM, and pepsin control, were subjected to SDS-PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and visualized using silver stain (Thermo Fisher) according to manufacturer’s instructions (n=2). Solubilized ECM protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) quantification (Pierce Chemical). Ten (10) µg of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic solubilized ECM and pepsin control was suspended in Laemmli buffer (R&D Systems) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), and separated in a 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel (Mini-PROTEAN TGX protein gel, Bio-Rad) at 120 V in running buffer (25 mM tris base, 192 mM glycine, and 0.1% SDS). Silver staining was applied to the gels using the Silver Stain Plus Kit (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and visualized using a ChemiDoc Touch Imaging System (BioRad).

2.2.3. Solubilized ECM mass spectrometry

The proteomic profile of human normal and tumor tissue, and normal and tumor ECM, was determined and compared (n=3, 5 technical replicates). Native tissue and ECM samples from the same tissues were cryomilled using liquid nitrogen and lyophilized before mass spectrometry analysis.

One mg of lyophilized tissue was weighed and processed as previously described (27). Briefly, tissues were homogenized by mechanical agitation (Bullet Blender®, Next Advance) in a CHAPS buffer containing 2mm glass beads. Following homogenization, tissues were sequentially extracted with vortexing and high-speed centrifugation in 8 M Urea, and CNBr buffers resulting in 3 fractions for each sample: (1) cellular fraction, (2) soluble ECM, and (3) insoluble ECM. ECM representative stable isotope labeled (SIL) polypeptides (QconCATs (28)) were spiked into each fraction at known concentrations prior to proteolytic digestion. Enzymatic digestion was carried out as previously described (29). In short, samples were reduced, alkylated and digested via filter assisted sample prep (FASP) and desalted by solid-phase extraction using C18 resin.

Samples were analyzed by both liquid chromatography-selected reaction monitoring (LC-SRM) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for targeted (quantitative) and global proteomics, respectively. Equal volumes of each post-digestion sample were combined and injected every fifth run and used to monitor technical reproducibility. LC-SRM and LC-MS/MS data was processed as previously described (30).

2.3. THP-1 Macrophage Cell Culture

A human mononuclear cell line THP-1 (ATCC) was expanded as previously described (31, 32) in culture media (Roswell Park Memorial Institute [RPMI], 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 1% penicillin/streptomycin). THP-1 cells were plated at 2 million cells/well and activated to naïve macrophages (M0) by 320 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 hrs. These cells were rested for 3d, and treated with one of the following for 24 hrs: solubilized normal, metaplastic, or neoplastic ECM hydrogel (250 µg/mL) from rat or human sources, positive control “M1”-like stimulus IFNγ (20 ng/mL)/LPS (100 ng/mL), positive control “M2”-like stimulus IL-4 (20 ng/mL), negative controls pepsin (25 µg/mL) or media alone. UBM (250 µg/mL) was added as a heterologous ECM control.

2.3.1. ECM effect on THP-1 macrophage gene expression

RNA was isolated (Qiagen RNeasy) from macrophages treated with rat ECM, transcribed to cDNA (Invitrogen cDNA RT kit) for qPCR using the SYBR green probe (BioRad), and tested for a panel of pro-inflammatory (“M1-like”) and anti-inflammatory (“M2-like”) genes in technical duplicates (n=4). Results were analyzed with the ∆∆Ct method, normalized to housekeeping gene βgus, and fold change was calculated against media treatment at 24 hrs. The significant genes were repeated with the same experimental design at 6 and 72h to investigate the effect of time upon gene expression.

Background levels of endotoxin, a ubiquitous laboratory contaminant and known M1 activator, were tested using Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (LAL) in the neutralized rat ECM hydrogels (5 mg/mL) (n=3), and sample endotoxin concentration was calculated using an endotoxin standard curve.

2.3.2. ECM effect on THP-1 macrophage secreted proteins

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to determine the presence of IFNγ, TNFα, and IL1RN in the supernatant of macrophages treated with rat normal, metaplastic and neoplastic ECM after 6 or 24 hrs. Supernatants were first centrifuged at 1500 rpm at 4°C for 10min to remove any particulate material. The ELISA for IFNγ (Human IFNγ ELISA Kit II, BD OptEIA), TNFα (Human TNF ELISA Kit II, BD OptEIA), and IL1RN (Human IL-1ra/IL-1F3, R&D Systems) was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions at the appropriate dilution (n=5, technical duplicate). To evaluate the similarity between rat and human ECM treatment on macrophages, the supernatant of macrophages treated with human normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM was similarly measured for TNFα concentration by ELISA (n=4, technical duplicates). The human ECM samples were either patient-matched (“n1”), distinctive (“n2”), or combined patient-matched (3 patients combined for “n3,” and 2 patients combined for “n4”).

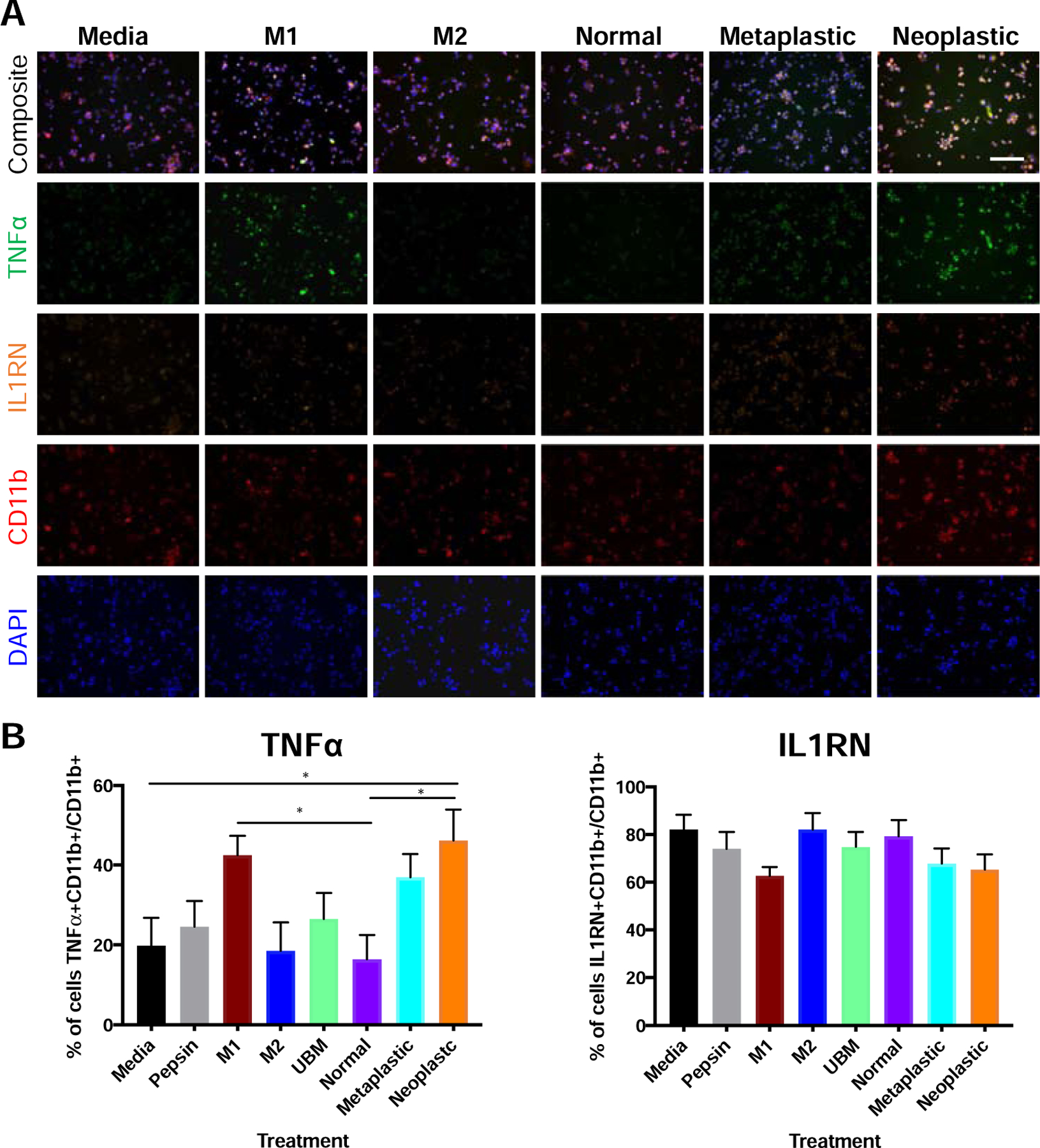

2.3.3. ECM effect on THP-1 macrophage cytosolic proteins

THP-1 cells were immunolabeled with TNFα and IL1RN antibodies after rat ECM, cytokine, or control treatment for 24h (n=3, 5 technical replicates), as described in 2.3. Cells were rinsed with PBS, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 20 min, and rinsed with PBS. Wells were blocked (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Tween 20, 2% bovine serum, and 4% goat serum in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies: polyclonal rat CD11b (1:150, Abcam 8878), polyclonal rabbit IL1RN (1:1000, Abcam 2573), and monoclonal mouse TNFα (1:100, Abcam 6671) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Wells were rinsed with PBS three times and cells were incubated with secondary antibodies AlexaFluor donkey anti-mouse 488, goat anti-rabbit 546, and goat anti-rat 596 (1:200 in blocking buffer) for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Wells were rinsed three times with PBS, incubated with DAPI for 5 min, rinsed with PBS and imaged at 20x magnification using a live-cell microscope. Exposure times were standardized by cytokine treated macrophage controls (i.e., “M1”-like and “M2”-like treatments). Three technical images were taken per sample. A CellProfiler pipeline that analyzed grayscale images of the unmixed channels was used to quantify the number of CD11b, TNFα, and IL1RN positive cells. Specifically, cells were defined as having a maximum diameter of 50 pixels. A threshold of 0.2, a smoothing scale of 1.35 (DAPI) or 2 (CD11b, TNFα, IL1RN), and a correction factor of 0.2 were used to classify positive staining. Objects outside those parameters or touching a border of an image were discarded, and intensity measurements were used to distinguish between multiple cells. Colocalization of positive immunolabeling and DAPI+ nuclei was used to determine the number of CD11b+, TNFα+ and IL1RN+ cells. Data are presented as the percentage of cells that were IL1RN+CD11b+ or TNFα+CD11b+ out of the total number of CD11b+ cells.

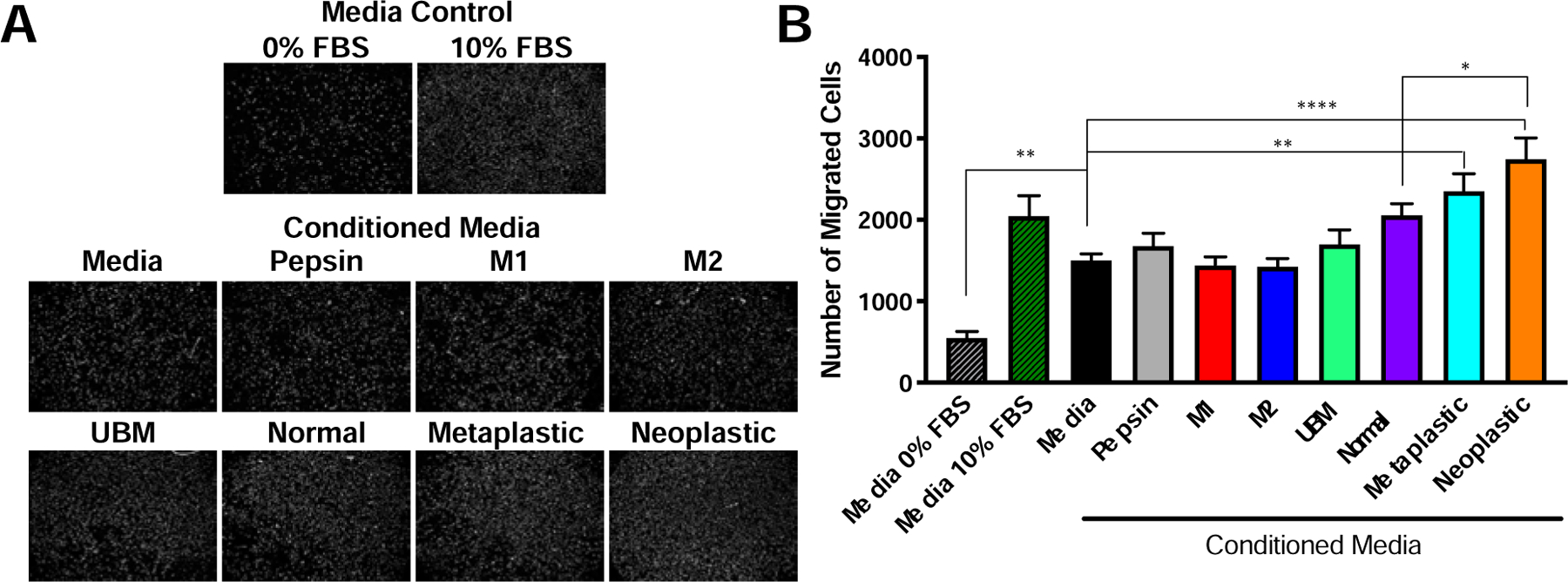

2.3.4. Effect of ECM conditioned macrophage secretome on Het-1A normal esophageal epithelial cell chemotaxis

Chemotaxis of an immortalized normal esophageal epithelial cell (Het-1A, ATCC) was investigated using the Boyden chamber assay (Transwell, 6.5 mm diameter; Corning, Lowell, MA). Het-1A cells were cultured in Bronchial Epithelial Basal Media (Lonza), with Bronchial Epithelial Growth Media Bullet Kit (Lonza) according to ATCC guidelines. Gentamycin-amphotericin B mixture from the Bullet Kit was not added to the media based on ATCC recommendations. The media was supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Fisher). Het-1A cells were expanded on flasks pre-coated with a solution of 0.01 mg/mL fibronectin, 0.03 mg/mL bovine collagen, and 0.01 mg/mL bovine serum albumin solution. Het-1A cells were split at 70–80% confluency, and detached with a solution of 0.05% (w/v) Trypsin-.53 mM EDTA, 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVV), and 0.35 mM EDTA solution in 1x PBS; and trypsinization was stopped with an equal volume of 0.1% Het-1A trypsin inhibitor.

“Conditioned media” was collected from THP-1 cells that had been pre-treated for 24h as described in 2.3 with rat ECM. The cells were then rinsed with PBS, and incubated in serum-free RPMI media for 5h. The Boyden Chamber was a polycarbonate membrane with 8 µm pores that was coated on both sides with rat collagen (0.05 mg/mL) in 0.02 N acetic acid for 1 hour at room temperature, rinsed 1x with PBS, and air-dried before being used in the Boyden Chamber assay. Conditioned media was added to the bottom of each Boyden well. Thirty thousand Het-1A cells in serum free media were added to the top of each Boyden well and allowed to migrate to the underside of the porous membrane for 24 hrs at 37°C in technical quadruplicates (n=3). The non-migratory cells on the upper membrane surface were removed with a scraper, the membrane was fixed for 5 minutes in 95% methanol, and the migratory cells attached to the bottom surface of the membrane were stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 0.1 M borate, pH 9.0, and 2% ethanol at room temperature. The membrane was mounted on a slide and stained with southern blot DAPI (SouthernBiotech). The number of migrated cells per well was imaged using absorbance 350 nm on the fluorescent live cell microscope (Zeiss Axiovert) and CellProfiler was used to count the number of nuclei/well.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc) with significance defined as P <0.05. Data is presented as means ± standard error of means (SEM) unless otherwise stated. Proteomics were analyzed by Principal Component Analysis, performed by MetaboAnalyst (v4.0) (33). Student’s un-paired t-tests were used to compare means between normal and neoplastic ECM. Gene expression results were analyzed by a 2-way ANOVA for the independent variables treatment and time. The Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to determine differences between treatment and media control at 6, 24, and 72hours. ELISA results were analyzed by a Kruskal Wallis nonparametric test, because the standard deviation was significantly different between treatment groups. One-way ANOVA was performed for the independent variable treatment at 6 and 24h. Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test was used to determine differences between treatment and media control. Immunolabeling and Boyden chamber results were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA for all comparisons against both media and normal ECM treatments with Dunnett’s multiple comparison post hoc analysis. Boyden chamber results (migrated Het-1A cells) were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA for the independent variable treatment. The Dunnett’s post hoc multiple comparisons test was used to determine differences between treatment and media or treatment and normal ECM.

3. Results

3.1. ECM hydrogel preparation

3.1.1. Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic tissue from rat and human esophagus can be decellularized with the same protocol

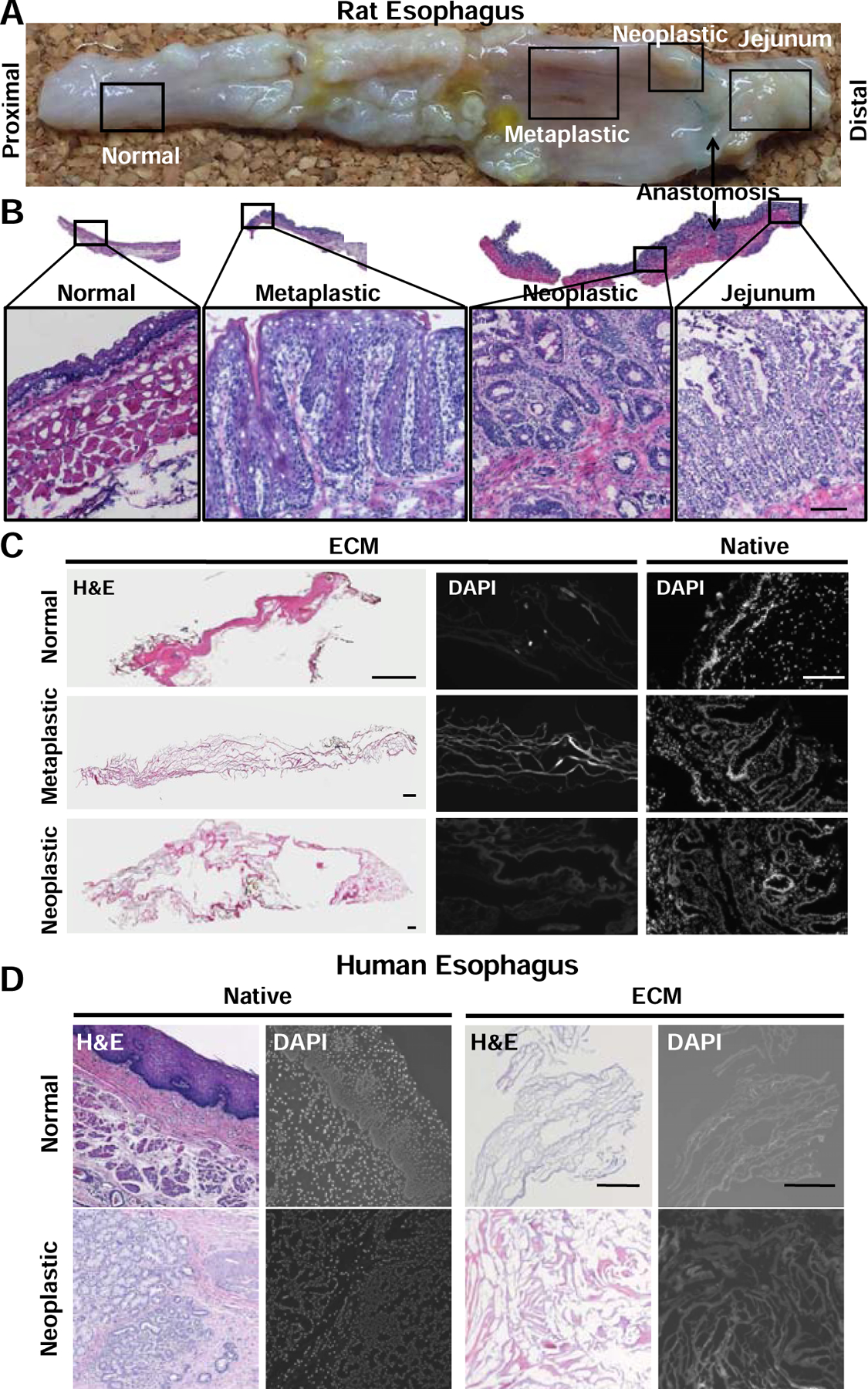

Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic esophageal ECM were prepared. The 3 tissue types were first macroscopically identified for the rat model of EAC (Figure 1A) and the pathology confirmed by histology with H&E staining (Figure 1B). Normal tissue showed a stratified, squamous epithelium; metaplastic tissue showed a villiform, columnar epithelium with goblet cells reminiscent of what is present in normal jejunum tissue; and neoplastic tissue showed glandular cells invading into the submucosa. The normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic tissues were decellularized using the same decellularization protocol, and were shown to be decellularized by absence of nuclei by H&E and DAPI staining (Figure 1C). The same decellularization protocol that was used for rat tissue resulted in decellularization of normal and neoplastic human tissue as determined by absence of nuclei (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. ECM preparation.

(A) An established rat surgical model of EAC (Levrat) progresses from normal squamous epithelium to metaplastic, villiform, columnar epithelium (Barrett’s esophagus) to neoplastic, glandular cell growth with invasion into the basement membrane (esophageal adenocarcinoma) over a period of 33 weeks. (B) Representative H&E confirmation of diseased regions. Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic tissue were dissected and pooled by diseased region. Scale bar = 25 µm (C) Decellularization efficacy assessed by absence of nuclei by H&E and DAPI stain (n=3). Scale bar = 250 µm. (D) Representative H&E and DAPI stains of human normal and human neoplastic native tissue, and ECM showing decellularization efficacy (n=3). Scale bar = 250 µm.

3.2. ECM hydrogel characterization

3.2.1. ECM hydrogels can be prepared and have a nanofibrous structure

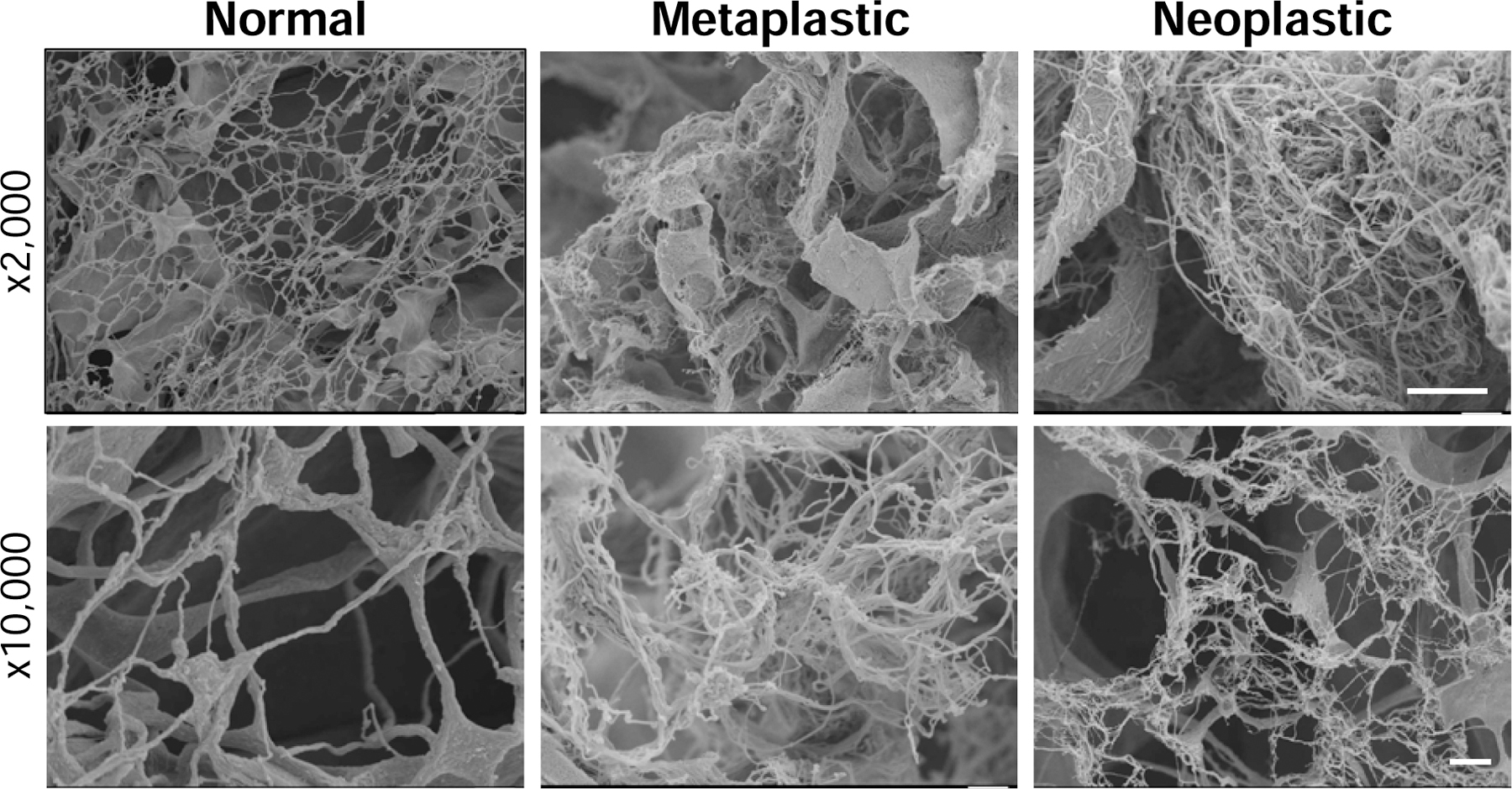

Hydrogels from the rat normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM were prepared by pepsin digestion and characterized with respect to their fibrous nanostructure; an important physical determinant of cell phenotype (9), by SEM. Contrary to our hypothesis, no differences between the 3 ECM hydrogels could be determined. However, all 3 ECM hydrogels showed a nanofibrous structure (Figure 2) consistent with other types of ECM hydrogels (34).

Figure 2. ECM hydrogel ultrastructure.

Normal, metaplastic and neoplastic ECM hydrogels from rat source tissue were prepared for scanning electron microscopy and imaged at 2,000x and 10,000x magnification (n=2, 5 technical replicates). The three types of ECM hydrogels show a porous fibrillar network. Scale bar = 10 µm for 2,000x magnification, 1 µm for 10,000x magnification.

3.2.2. Solubilized metaplastic and neoplastic ECM show a distinct chromatographic profile compared to solubilized normal ECM

SDS-PAGE with silver stain was performed to qualitatively evaluate the protein profiles of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM. Rat normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM showed distinctive chromatographic profiles (Figure S1), suggesting that biochemical differences exist and these differences are retained following decellularization because the same decellularization protocol was used for all source tissues. Hence, the biochemical profile of normal and neoplastic ECM was further evaluated by mass spectrometry.

3.2.3. Global mass spectrometry and targeted proteomics shows a distinctive neoplastic ECM signature (COL8A1, lumican, elastin)

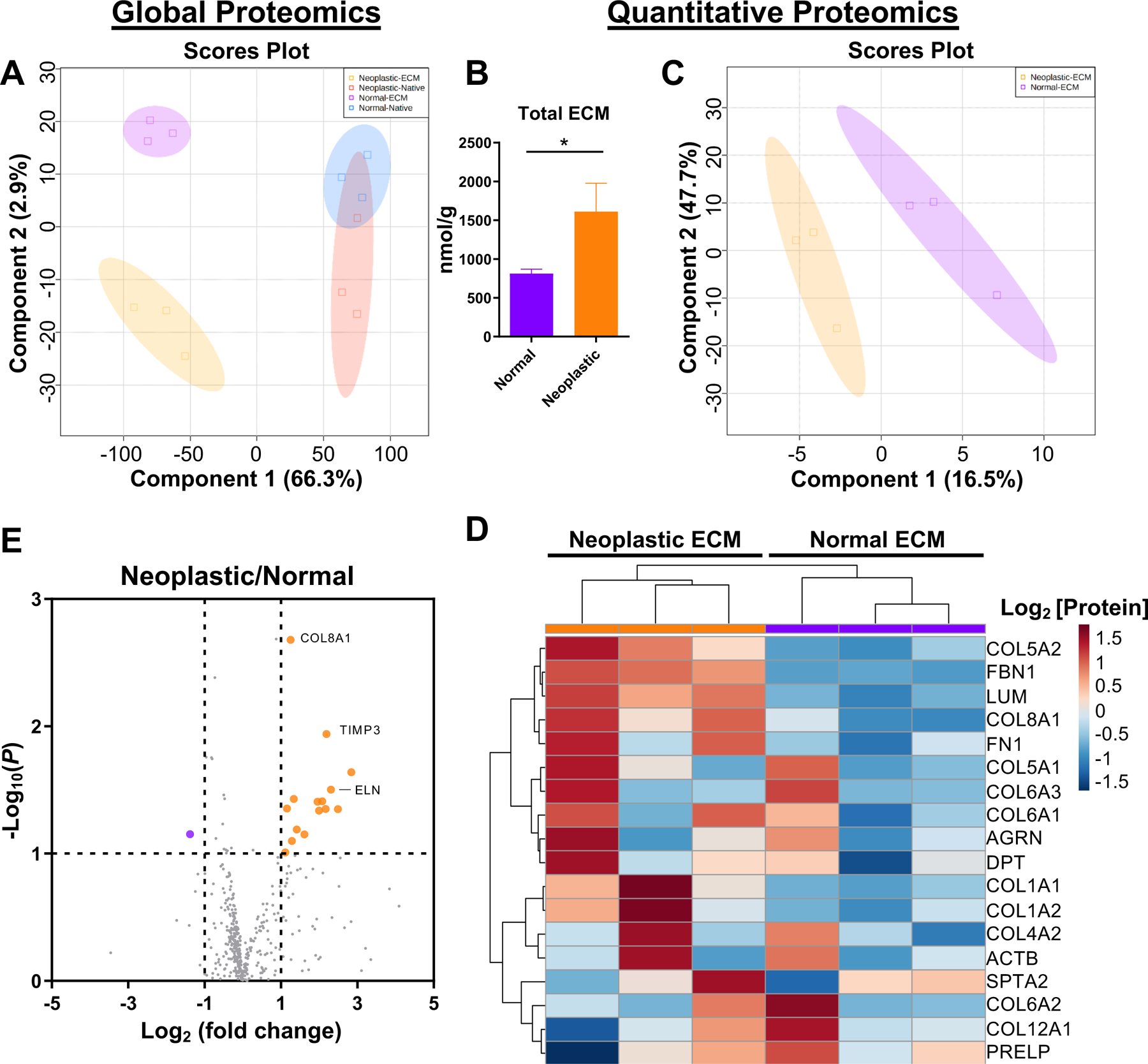

Two proteomic analyses were performed, global mass spectrometry and targeted proteomics, to determine the proteins differentially expressed between human normal and neoplastic ECM, and corresponding native control tissue.

Global mass spectrometry and subsequent principal component analysis (PCA), showed that the protein profile of human normal versus neoplastic native tissue was relatively similar as noted by the overlap in 95% confidence intervals (Figure 3A). However, the normal versus neoplastic ECM had distinct protein profiles (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Global and targeted proteomic analysis of normal and neoplastic ECM.

(A,E) Global mass spectrometry analysis and (B-D) targeted proteomic analysis of human normal and neoplastic ECM (n=3, 5 technical replicates). (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of human normal and neoplastic ECM and native tissue by global proteomic analysis. (B) Nanomolar concentration of total ECM per gram of tissue for normal and neoplastic tissue by targeted proteomics (n= 3, means ± SEM). * P < 0.05. (C) Partial least squares discriminate analysis (PLSDA) analysis showing compositional differences between normal and neoplastic ECM by targeted proteomics. (D) Hierarchical clustering analysis of 18 ECM and ECM-associated proteins quantified in all neoplastic and normal ECM samples by targeted proteomics, presented as a heat map, with log2 transformed protein concentration (nmol/g). (E) Volcano plot of differentially expressed proteins in neoplastic ECM to normal ECM (fold change) by global proteomics. Fold change threshold set to >2 or <−2, significance threshold set to P < 0.05, student’s t-test. Labeled proteins indicate ECM and ECM-associated proteins.

Quantitative proteomics targeting ECM and ECM-associated proteins was used to further characterize and compare the normal and neoplastic ECM to the respective native tissue samples (Figure 3B–D, Table 2, complete data set in Table S1). The human neoplastic tissue yielded almost twice the total ECM as the normal tissue (1.8-fold change, P = 0.03) (Figure 3B). Decellularization resulted in near complete depletion of cytoskeletal and cellular proteins (<0.1% remaining) (Table 2). Collagen alpha-1/2(I) (COL1A1/2) and collagen alpha-1/2(V) (COL5A1/2) accounted for more than 98% of the quantifiable proteins in the resulting normal and neoplastic ECM (Table S1). Collagen alpha-1(III) (COL3A1) is notably missing from the quantitative proteomics due to lack of a suitable stable isotope labeled probe at the time of the study, however, is represented near collagen alpha-1(I) (COL1A1) levels in the global proteomics.

Table 2. Quantitative proteomics of human normal and neoplastic tissue.

Absolute quantification (nmol/g) of proteins in normal and neoplastic human esophageal tissue before decellularization (“native”) and after decellularization (“ECM”) (n=3, 5 technical replicates). Each sample was divided into 2 parts for native and ECM analysis and weighed (wet weight) to provide a percentage (%) of the total wet sample weight and to normalize the protein abundance values in native tissue and ECM. Proteins are shown separated by gene ontology class and labeled by their Matrisome classification. Protein retention (ratio of ECM/Native protein abundance) is labeled by a color gradient from highly retained proteins in the ECM (“blue”) to not highly retained proteins (“red”). FC - Fold change (Neoplastic ECM/normal ECM). Orange FC - increased (>2 fold) in neoplastic ECM, purple FC - increased (>2 fold) in normal ECM. “Neoplastic” - neoplastic ECM only, “Normal” - normal ECM only. “∅” - not measured in either ECM. Significant P value in green, not reported if incomplete protein detection in 1 or more sample.

| Class | Protein | Gene | Matrisome | Avg Protein Retention (ECM/Native) % | ECM Comparison Neoplastic/Normal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Neoplastic | FC | Ttest | ||||

| Basement Membrane | Collagen alpha-1(IV) c | COL4A1^ | Collagen | 1% | 1% | 0.38 | 0.640 |

| Collagen alpha-2(IV) c | COL4A2^ | Collagens | 4% | 30% | 3.50 | 0.492 | |

| Collagen alpha-5(IV) c | COL4A5 | Collagen | 6% | 13% | 0.57 | 0.634 | |

| Collagen alpha-6(IV) c | COL4A6 | Collagens | 1% | 0% | Normal | ||

| Perlecan | HSPG2 | Proteoglycans | 4% | 1% | 0.09 | ||

| Perlecan | HSPG2^ | Proteoglycans | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Laminin alpha-2 | LAMA2 | ECM Glycoproteins | 8% | 68% | 0.91 | ||

| Laminin alpha-4 | LAMA4 | Glycoprotein | 1% | 4% | 0.32 | ||

| Laminin alpha-5 | LAMA5 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | 0.68 | ||

| Laminin beta-1 | LAMB1 | ECM Glycoproteins | 5% | 39% | 1.32 | ||

| Laminin beta-2 | LAMB2 | ECM Glycoproteins | 0% | 109% | Neoplastic | ||

| Laminin Gamma-1 | LAMC1 | Glycoprotein | 1% | 7% | 1.12 | ||

| Nidogen-1 | NID1 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Nidogen-2 | NID2 | ECM Glycoproteins | 0% | 2% | Neoplastic | ||

| Agrin(iso 2,3,4,5,&6) | AGRN^ | Glycoprotein | 10% | 54% | 1.48 | 0.583 | |

| Cytoskeletal | Actin (All Isoforms) | ACT | Cellular | 0% | 3% | 16.89 | 0.291 |

| Actin, cytoplasmic1/2 | ACTB | Cellular | 0% | 2% | 1.61 | 0.658 | |

| Desmin | DES | Cellular | 0% | 0% | 0.38 | ||

| Plectin | PLEC | Cellular | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Spectrin alpha chain, n | SPTA2 | Cellular | 16% | 92% | 1.26 | 0.534 | |

| Vimentin | VIM | Cellular | 0% | 0% | Normal | ||

| Myosin(Myosin-3,4,6,7) | MYH^ | Cellular | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Tubulin beta-4B chain | TUBB^ | Cellular | 0% | 3% | 0.83 | ||

| Collagen | Collagen alpha-1(XII) c | COL12A1 | Collagens | 13% | 25% | 0.58 | 0.496 |

| Collagen alpha-1(XIV) | COL14A1 | Collagen | 12% | 51% | 1.44 | 0.667 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(I) ch | COL1A1 | Collagen | 115% | 197% | 1.99 | 0.096 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(I) ch | COL1A1^ | Collagen | 14% | 125% | 1.11 | 0.823 | |

| Collagen alpha-2(I) ch | COL1A2 | Collagen | 125% | 188% | 1.97 | 0.127 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XXV | COL28A1 | Collagens | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(II) ch | COL2A1 | Collagens | 10% | 123% | 1.65 | 0.474 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(V) ch | COL5A1 | Collagen | 67% | 162% | 1.28 | 0.662 | |

| Collagen alpha-2(V) ch | COL5A2 | Collagen | 122% | 586% | 2.30 | 0.034 | |

| Matricellular | Fibulin 3 | EFEMP1 | Glycoprotein | 1% | 7% | 1.38 | |

| Fibulin 5 | FBLN5 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Periostin | POSTN | Glycoprotein | 31% | 6% | 0.96 | ||

| Thrombospondin 1 | THBS1 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Tenascin-C(Iso1,2,3,4 | TNC | ECM Glycoproteins | 2% | 55% | 2.37 | ||

| Tenascin-X | TNXB | Glycoprotein | 0% | 6% | Neoplastic | ||

| Other Cellular | Glyceraldehyde-3-pho | GAPDH | Cellular | 2% | 13% | 0.83 | 0.761 |

| Histone H1(H1.1,H1.2 | H1^ | Cellular | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Histone 2A(H2A-A-K) | H2A^ | Cellular | 0% | 2% | 1.85 | ||

| Other ECM | Annexin A2 | ANXA2 | ECM-affiliated | 1% | 5% | 0.52 | 0.065 |

| Asporin | ASPN | Proteoglycan | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(VIII) | COL8A1 | Collagens | 13% | 306% | 6.17 | ||

| Chondroitin sulfate pro | CSPG4 | ECM-affiliated Proteins | 0% | 0% | ∅ | 0.469 | |

| Galectin-1 | LGALS1 | ECM-affiliated Proteins | 0% | 2% | 2.33 | ||

| Galectin-3 | LGALS3 | ECM-affiliated | 0% | 0% | ∅ ∅ | ||

| Matrix Gla Protein | MGP | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | 3.70 | ||

| Mimecan/Osteoglycin | OGN | Proteoglycan | 1% | 2% | |||

| Sushi repeat-containin | SRPX | ECM Glycoproteins | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Transglutaminase 2 | TGM2 | ECM regulator | 2% | 2% | 0.34 | ||

| Secrete | Target of Nesh-SH3 | ABI3BP | ECM Glycoproteins | 5% | 6% | 0.48 | 0.376 |

| Adiponectin | ADIPOQ | Glycoprotein | 1% | 380% | 28.73 | ||

| Transforming growth f | TGFBI | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Structural ECM | Biglycan | BGN | Proteoglycan | 0% | 0% | ∅ | |

| Collagen alpha-1(XVIII | COL18A1 | Collagens | 2% | 7% | 1.38 | 0.737 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(VI) c | COL6A1 | Collagen | 6% | 14% | 2.04 | 0.259 | |

| Collagen alpha-2(VI) c | COL6A2 | Collagens | 0% | 0% | 0.79 | 0.727 | |

| Collagen alpha-3(VI) c | COL6A3 | Collagens | 3% | 10% | 1.94 | 0.684 | |

| Decorin | DCN | Proteoglycan | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Dermatopontin | DPT | Glycoprotein | 29% | 81% | 1.42 | 0.314 | |

| Emilin 1 | EMILIN1 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Fibulin 1 | FBLN1 | Glycoprotein | 2% | 38% | 1.78 | ||

| Fibrillin 1 | FBN1 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 9% | 7.80 | 0.060 | |

| Fibromodulin | FMOD | Proteoglycans | 0% | 0% | Neoplastic | ||

| Fibronectin 1(Anastelli | FN1 | ECM Glycoproteins | 1% | 3% | 2.31 | 0.101 | |

| Latent-transforming gr | LTBP1 | ECM Glycoproteins | 0% | 287% | Neoplastic | ||

| Latent-transforming gr | LTBP4 | ECM Glycoproteins | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Lumican | LUM | Proteoglycans | 4% | 37% | 5.45 | 0.008 | |

| Microfibrillar-associate | MFAP2 | Glycoprotein | 0% | 0% | ∅ | ||

| Prolargin | PRELP | Proteoglycans | 2% | 6% | 0.67 | 0.422 | |

| Versican core protein | VCAN | Proteoglycans | 1% | 2% | 1.45 | ||

| Vitronectin | VTN | Glycoprotein | 2% | 1% | 1.10 | ||

The difference between the normal and neoplastic ECM was shown to be due to differences in ECM composition as represented by partial least squares discriminate analysis (PLSDA) of the targeted proteomics (Figure 3C). Hierarchical clustering analysis of 18 ECM and ECM-associated proteins identified in all samples showed unique protein signatures for normal and neoplastic ECM (Figure 3D). Among the top 5 proteins there was markedly increased collagen alpha-2(V) (COL5A2, 2.3-fold change, P = 0.03), fibrillin-1 (FBN1, 7.8-fold change, P = 0.06), lumican (LUM, 5.5-fold change, P = 0.008), and collagen alpha-1(VIII) (COL8A1, 6.2-fold change, P = 0.07) in neoplastic ECM compared to normal ECM (Figure 3D, Table 2).

Utilizing the global proteomics dataset to find additional ECM proteins not represented by the targeted proteomics library, elastin and collagen alpha-1(VIII) were among the proteins showing the greatest difference between the neoplastic and normal ECM (Figure 3E, Table S2). Collagen alpha-1(VIII) was increased in neoplastic ECM compared to normal ECM (2.4-fold change, P < 0.001). Elastin was increased in neoplastic ECM compared to normal ECM (5.0-fold change, P = 0.009).

In summary, the 3 proteins that had a > 2-fold change and statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) across at least 1 of the 2 proteomic methods were: lumican, COL8A1, and elastin; and notably all 3 were increased in neoplastic ECM compared to normal ECM.

3.3. Metaplastic and neoplastic ECM activate macrophage TNFα and IL1RN signaling and neoplastic ECM increases macrophage TNFα secretion

To determine the biochemical effect of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM upon macrophage activation, the solubilized ECM types were added to the cell culture media as previously described (34, 35). Because the solubilized (liquid) phase form of ECM was used, the physical properties of the hydrogel (e.g., stiffness, porosity) were not a factor in the present results.

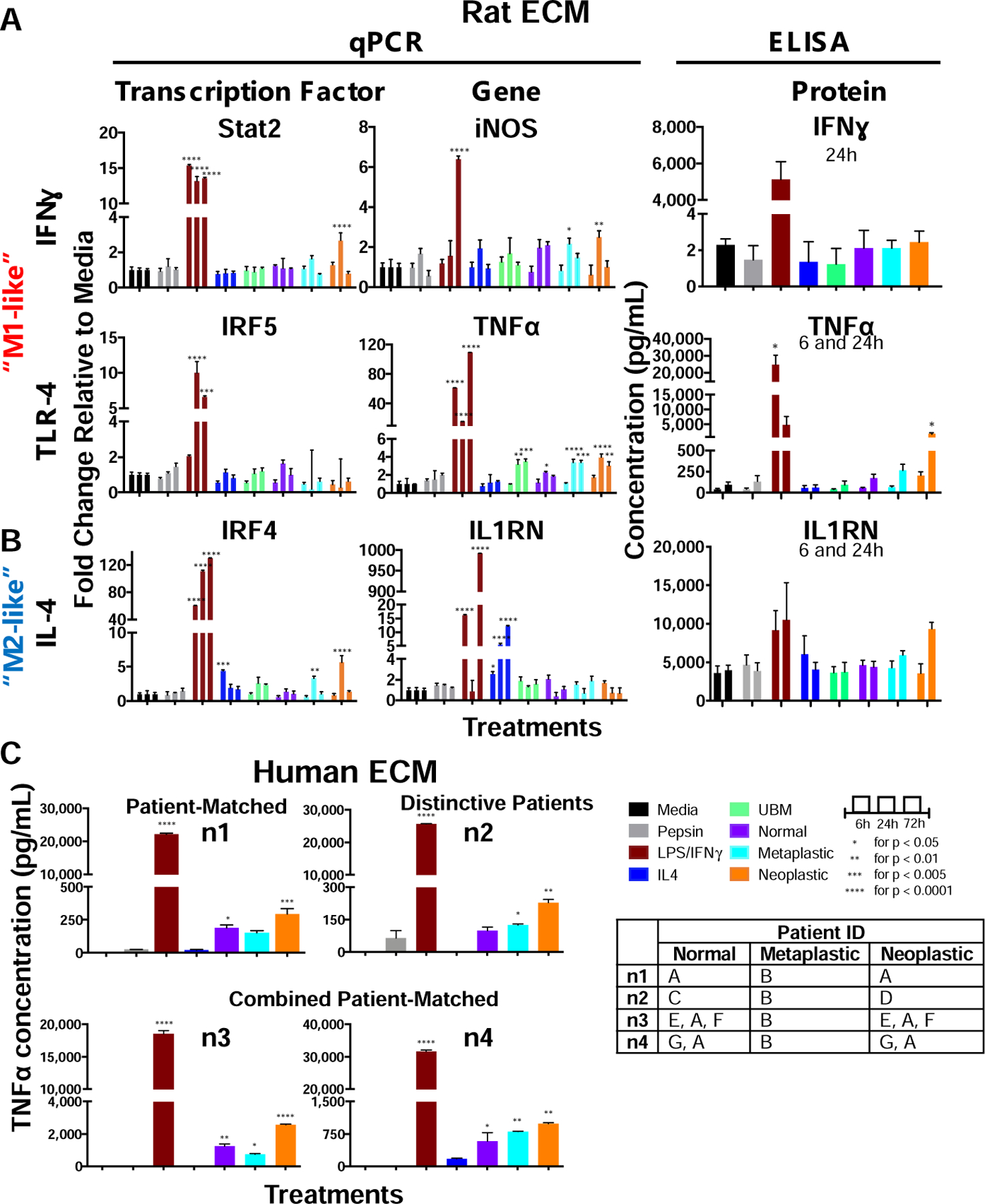

Transcription factors and downstream genes are shown for the pro-inflammatory (Figure 4A) and anti-inflammatory (Figure 4B) panel of markers with differences relative to media. For the pro-inflammatory IFNγ signaling pathway, neoplastic ECM increased Stat2 transcription factor expression (2.7-fold, P <0.001) at 24h. The downstream gene iNOS was increased with metaplastic ECM (2.2-fold, P = 0.03) and neoplastic ECM (2.5-fold, P = 0.005) at 24 hours. However, secreted IFNγ protein was not changed with normal, metaplastic, or neoplastic ECM treatment at 24 hours. For the pro-inflammatory TLR-4 signaling pathway, there was a basal expression of TNFα with normal ECM treatment at 24 hours (2.3-fold, P = 0.04), but increased TNFα gene expression was shown for metaplastic ECM (3.4-fold, P < 0.001) and neoplastic ECM (4.0-fold, P < 0.001) at 24 hours, and for metaplastic ECM (3.4-fold, p<0.001) and neoplastic ECM (3.0-fold, P = 0.002) at 72 hours. TNFα secreted protein was increased with neoplastic ECM treatment at 24h (19.1-fold, P = 0.049).

Figure 4. Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM promote a distinctive M1-like and M2-like signature.

A human mononuclear cell line (THP-1) was activated to naïve macrophages (M0). The M0 macrophages were treated with normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM hydrogels (250 µg/mL) from rat source tissue, positive controls for M1-like activation (LPS/IFNγ) and M2-like activation (IL-4) or negative controls (pepsin, media) for 24 hours and tested for a panel of (A) pro-inflammatory and (B) anti-inflammatory genes and transcription factors. Heterologous urinary bladder matrix (UBM) was included as a heterologous tissue control, as a biomaterial known to promote an M2-like activation. (n=4, technical duplicates, means ± SEM). (C) TNFα concentration of THP-1 cells treated with normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM from human source tissue for 24 hours by ELISA (n=4, technical duplicates). Patient ID table shows the combination of samples used from 7 patients (A-G). The normal and neoplastic ECM was patient-matched (“n1”), distinctive (“n2”), or combined patient-matched (“n3”, “n4”). Only 1 Barrett’s (metaplastic) human tissue sample was available and used for all 4 replicates. (means ± SD). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.005, **** P < 0.0001.

For the anti-inflammatory IL-4 signaling pathway, there was increased expression of the transcription factor IRF4 with metaplastic ECM (3.3-fold, P = 0.009) and neoplastic ECM (5.6-fold, P = 0.001) treatment at 24h. Secreted IL1RN protein trended toward an increase with neoplastic ECM treatment at 24 hours, but was not significant (2.4-fold, P = 0.07).

TNFα was the most significant macrophage marker with rat ECM treatment as determined by qPCR and ELISA. To determine if human ECM similarly activates macrophage toward TNFα, 7 de-identified patient (human) samples were decellularized and evaluated (Figure 4C). The normal and neoplastic ECM samples were patient-matched (“n1”), distinctive (“n2”), or combined patient-matched (3 patients combined for “n3” and 2 patients combined for “n4”). Only 1 metaplastic patient sample was available and used for all replicates. The human ECM results corroborate the rat ECM with increased TNFα concentration in macrophages compared to media control in 4 of 4 samples; and furthermore showed on average ~ 2-fold higher concentration compared to normal ECM. Furthermore, the results of the patient-matched samples (n1, n3–4) suggest that there is higher TNFα activation from neoplastic ECM compared to normal ECM within a patient’s esophagus.

Other genes tested that did not show significant differences by one-way ANOVA at 24h were: Stat5b, Stat5a, IRF3 (M1) and KLF4, Stat6, PPARγ, Stat3, and CD206 (M2) (Figure S2), and were not further evaluated. Endotoxin, a ubiquitous laboratory contaminant and known M1 activator, was measured to evaluate potential non-specific activation of the pro-inflammatory pathway. Endotoxin concentration for rat normal (1.2 ± 0.7 EU/mL), metaplastic (0.2 ± 0.2 EU/mL), and neoplastic (2.4 ± 0.1 EU/mL) ECM was not different to pepsin (2.1 ± 1.3 EU/mL) control (Figure S3), suggesting the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling was due to the composition of proteins in the normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM.

Table 3 summarizes the macrophage activation markers in the present study with respect to canonical markers of M1, M2, and Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAM) from the literature.

Table 3.

Summary of macrophage activation markers.

| Macrophage Activation | Description | Markers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | “M1-like” | • Activated by IFNγ, LPS, and TNFα (3) • Protect against pathogens (3) |

•Secrete high nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokines (3) •IL-12high, IL-10low, IL-6high and TNFαhigh (3) |

| “M2-like” | • Activated by IL-4 and IL-13 (3) • Scavenge debris, promote angiogenesis, and recruit cells involved in constructive tissue remodeling (3) |

Secrete high TGF-β1 and arginase (2) IL-10high IL-12low; IL-1RAhigh, and IL-1 decoyhigh (2, 3) |

|

| TAM | • Subtype of M2 (4) • Non-cytotoxic toward tumor cells; inefficient to trigger an adaptive immune response (2) |

Secrete low NO and reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) (36) 1L-10high; IL-12low, IL-1βlow, TNFαlow, IL-6 low (36) Low antigen presenting (2) |

|

| Present Study | M(normal ECM) | • Activated by 250 µg/mL | TLR-4: TNFα high 24h |

| M(metaplastic ECM) | • Activated by 250 µg/mL |

IFNγ: Stat2high 24h TLR-4: TNFα high 24 and 72h IL-4: IRF4 high at 24h Increase epithelial cell migration |

|

| M(neoplastic ECM) | • Activated by 250 µg/mL | • IFNγ: Stat2high 24h, iNOShigh 24h • TLR-4: TNFα high 24 and 72h, secrete TNFαhigh 24h, immunolabel TNFα high • IL-4: IRF4 high at 24h Increase epithelial cell migration |

|

| M(UBM) | • Activated by 250 µg/mL | • TLR-4: TNFα high 24 and 72h |

3.3.1. TNFα+ expression is increased in macrophages with neoplastic ECM treatment

Immunolabeling of pro-inflammatory TNFα and immunomodulatory IL1RN was performed to corroborate the qPCR and ELISA results (Figure 5A; pepsin and UBM controls in Figure S4) on ECM from rat source tissue. The percentage of TNFα+ macrophages out of total macrophages increased with increasing ECM tumorigenicity as shown in the panel 24h after treatment, with an increase in expression in neoplastic ECM (46.3 ± 7.6 %) compared to media (19.9 ± 6.9%, P = 0.04) and to normal ECM (16.5 ± 6.0%, P = 0.02) (Figure 5B). IL1RN did not show any change between ECM treatments (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Immunolabeling of ECM treated macrophages.

A human mononuclear cell line THP-1 was activated to naïve macrophages (M0). The M0 macrophages were treated with normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM hydrogels (250 µg/mL) from rat source tissue; positive controls for M1-like activation (LPS/IFNγ) and M2-like activation (IL-4); negative controls (pepsin, media); or heterologous urinary bladder matrix (UBM) for 24 hours. (A) Macrophages were fixed and labeled with TNFα (“M1” like) in green, IL1RN (“M2 like”) in orange, pan macrophage marker CD11b in red, and DAPI in blue. Representative images shown. Scale bar = 150 µm. Pepsin and UBM control images are in Figure S4. (B) Images were quantified in CellProfiler. * P < 0.05 (n=3, 5 technical replicates, 3 images/replicate, means ± SEM).

3.3.2. The secretome of macrophages treated with metaplastic and neoplastic ECM increases normal esophageal epithelial cell migration

The paracrine effect of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM treated macrophages was investigated. “Conditioned media” (i.e., the secretome of macrophages that have been pre-treated for 24h with solubilized ECM added to the cell culture media) was used in a Boyden Chamber assay to quantify chemotaxis upon normal esophageal epithelial cells (Het-1A) (Figure 6). Metaplastic ECM (2,352 ± 211.8 cells, P = 0.003) and neoplastic ECM (2,745 ± 258.4 cells, P < 0.001) conditioned media increased esophageal epithelial cell Het-1A chemotaxis compared to media control (1,503 ± 79.8 cells). Importantly, neoplastic ECM conditioned media increased migration compared to normal ECM conditioned media (2,057 ± 146 cells, P = 0.04).

Figure 6. Metaplastic and neoplastic ECM increased migration of normal esophageal epithelial cells through macrophage paracrine effects.

Macrophages were conditioned with medium, M1-like positive stimulus (LPS/IFNγ), M2-like positive stimulus (IL-4), pepsin (25 µg/mL), UBM (250 µg/mL), or normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM (250 µg/mL) from rat source tissue for 24 hours. Heterologous urinary bladder matrix (UBM) was included as a heterologous tissue control, as a biomaterial known to promote an M2-like activation. The secretome of the conditioned macrophages was collected for 4 hours in serum-free medium and used as a chemoattractant in a Boyden chamber assay using normal esophageal epithelial cells (Het-1A). (A) Representative images of migrated Het-1A cells to each treatment and (B) quantification (n= 3, technical quadruplicates, means ± SEM). * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study show that ECM isolated from normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic esophageal tissue cause distinctive macrophage activation profiles, specifically with respect to pro-inflammatory (IFNγ, TNFα) and immunomodulatory (IL1RN) gene expression; and paracrine effects upon esophageal epithelial cell migration. Neoplastic tissue had ~2x increased ECM protein per dry weight, and neoplastic ECM had higher concentrations of lumican, COL8A1, and elastin compared to normal ECM. The results suggest that ECM signals changing with neoplastic progression can be retained following decellularization because the three types of ECM were decellularized using the same protocol to eliminate the variable of processing. Neoplastic ECM had the most pronounced effect upon naïve macrophage activation (TNFα+) via secreted products and immunolabeling, and influenced a non-malignant esophageal epithelial cell to behave more like a neoplastic cell with increased migration, consistent with the premise of dynamic reciprocity (37). Metaplastic ECM showed similar but less pronounced effects than neoplastic ECM suggesting that the neoplastic signals within the ECM progressively accumulate.

4.1. Solubilized ECM from normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic esophageal ECM induced a distinct macrophage activation state. Metaplastic and neoplastic ECM promoted TNFα+ macrophages and increased epithelial cell migration in a progressive manner.

Macrophages activate at a site of tissue injury or within a tumor on a spectrum from pro-inflammatory (“M1”-like) to immunomodulatory (“M2”-like) in response to microenvironmental signals (38). M1 and M2 are characterized by different functional characteristics including released growth factors, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (3). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) are characterized as a subtype of M2, involved in immunomodulation to permissively allow neoplastic cells to proliferate and survive (2, 4). It was hypothesized that ECM derived from Barrett’s esophagus, which represents a chronic inflammatory state, would activate macrophages toward an “M1-like” state, and the neoplastic ECM would activate macrophages toward an “M2”-like state (4). However, this hypothesis was not supported by the results of the present study.

Signaling pathways were characterized with transcription factors, downstream genes, and secreted products. For the pro-inflammatory (“M1”) TLR-4 signaling, metaplastic and neoplastic ECM increased TNFα gene expression at 24 and 72h, and normal ECM increased THP-1 TNFα gene expression at 24h from rat source tissue. Only neoplastic ECM increased TNFα secreted protein expression by ELISA compared to media at 24h. These results were corroborated by immunolabeling with neoplastic ECM increasing the percentage of TNFα+ macrophages compared to media and to normal ECM treatment after 24h. Furthemore, in a cohort of 7 patient (human) samples, neoplastic ECM showed ~ 2x higher TNFα expression compared to normal ECM, corroborating the rat ECM results. Three (3) of the 4 replicates were “patient-matched” for the neoplastic and normal ECM, suggesting that the differences in the biochemical signals exist within a patient’s own esophageal ECM. TNFα is upregulated in GERD (39), along with other pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-10; and is further upregulated from BE to EAC (40). TNFα is released by macrophages as well as cancer cells, fibroblasts, and epithelial cells in EAC and other cancer types, with the possibility for paracrine and autocrine feedback (40–42). In the context of other inflammatory driven cancers (e.g., ovarian, breast, prostate, bladder, colorectal) (40), TNFα increased epithelial cell proliferation (40), MMP secretion (40), ROS production to directly oxidize DNA (41), and epithelial-mesenchymal-transition (42); increased cancer cell invasion (42); and caused macrophage-mediated T cell suppression (43). The pro-tumoral TNFα functions may also be occurring during EAC progression. The present study adds to the literature by showing the isolated role of metaplastic and neoplastic ECM as an initiating signal to activate macrophages toward TNFα+.

Metaplastic and neoplastic ECM from rat source tissue induced a macrophage secretome (“conditioned media”) that increased epithelial cell migration compared to media alone, and neoplastic ECM conditioned media also increased epithelial cell migration compared to normal ECM conditioned media. The chemoattractant signals in the macrophage secretome remain to be determined, but it is possible that TNFα could be a contributing factor as it increased neoplastic cell invasiveness in a co-culture with macrophages (4).

Pro-inflammatory IFNγ signaling was also implicated in the present study, specifically an increase in Stat2 transcription factor gene expression with neoplastic ECM treatment and iNOS gene expression with metaplastic and neoplastic ECM treatment at 24h using rat source tissue. However, secreted IFNγ was not increased at 24h by ELISA. iNOS and Stat2 may be activating other downstream pro-inflammatory secreted products. IFNγ inducible cytokines can also be inhibited by IL-4 (2), so it is possible cross-talk may have occurred between the IL-4 and IFNγ pathways in the present study.

For the immunomodulatory (“M2”) IL-4 signaling, metaplastic and neoplastic ECM increased THP-1 IRF4 transcription factor at 24h using rat source tissue. Neoplastic ECM trended toward increased secreted IL1RN, but was not significant in the secreted protein level and was not corroborated with immunolabeling.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the rat neoplastic ECM did not show activation of M2 signaling pathways other than IRF4 gene expression, but rather, showed increased pro-inflammatory Stat2, iNOS, and TNFα gene expression and TNFα protein expression. TNFα is not a canonical TAM marker (4). There are several possible explanations for this finding. The difference could be because the TAM response has been characterized with respect to specific cytokines (4) or more recently singular ECM fragments (21, 44), but not by the isolated role of the biochemically complex ECM in vitro. Evaluating the macrophage response to the ECM, alone and in combination with cytokines, can lead to a mechanistic understanding of the competing stimuli occurring in vivo for the TAM phenotype. In turn, an effective M1 tumor rejection therapy may be possible by changing the concentration or temporal presentation of TNFα. For example, a chronic, low dose of TNFα is a tumor promoter, but a high, concentrated TNFα dose can destroy tumor blood vessels (41). M1 activated iNOS+ macrophages were shown to be necessary and sufficient for the shrinkage of pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumors. Finally, it remains unknown if the TNFα+ signature is specific to esophageal cancer ECM activated macrophages. The findings suggest the need to profile the ECM of diverse cancer types to determine unique and conserved macrophage phenotype markers in response to neoplastic ECM.

An important question to the field of immunology and regenerative medicine is whether neoplastic ECM promotes the same phenotype as biomaterials known to promote an “M2-like” phenotype, specifically, biomaterials composed of ECM derived from normal tissues (45). ECM-based biomaterials are commercially available, and have been used in the reconstruction of functional tissue following cancer resection without cancer recurrence, including esophageal cancer patients (46). The present study investigated urinary bladder matrix (UBM) as a heterologous ECM that is well-characterized and has been shown to promote immunomodulation and tissue remodeling (47, 48). Naïve (M0) macrophage treated with UBM showed a more pro-inflammatory phenotype (Figure 4, Figure S2), which is consistent with a previously published study (32). Huleihel et al. (32) further showed that UBM promoted an M2-like phenotype when macrophages were first challenged with LPS/IFNγ, a condition that was not explored in the present study. Nonetheless, in the present study UBM and neoplastic ECM showed distinct gene and protein expression for the pro-inflammatory pathways IFNγ, TLR-4 and immunomodulatory IL1RN markers, suggesting the two ECM are distinct subtypes. The results are also in agreement with a study by Wolf et al. (45) wherein UBM co-injected with melanoma cancer cells showed a distinctive M2-like lymphocyte and macrophage phenotype compared to saline co-injected with cancer cells (representing the basal “TAM” phenotype) and was correlated with decreased and delayed tumor formation. In other words, the Wolf et al. study showed the importance of understanding the immune activation state to UBM versus TAM, with its clinically- relevant, functional consequences. The present study adds to the Wolf et al. study with the separate but related question that UBM and neoplastic ECM also distinctly activate immune cells. The findings reinforce the importance of using more than one M1 or M2 marker to characterize and distinguish these subtypes.

4.2. Neoplastic ECM signature contains COL8A1, lumican, and elastin

The specific signals within the neoplastic ECM that activate macrophages toward TNFα+ are not known. The human normal and neoplastic ECM was shown to retain the biochemical complexity of the native tissue in the present study. Increased ECM proteins were measured per gram dry weight in neoplastic tissue compared to normal tissue. The increased ECM protein per gram dry weight in the neoplastic tissue is consistent with the known increased ECM deposition by fibroblasts during tumorigenesis (8). Over 98% quantifiable proteins in the resulting normal and neoplastic ECM were COL1A1/2, COL5A1/2, and COL3A1. Collagen is one of the most readily recognized proteins in cancer (49), and is associated with increased stiffness of the matrix, which could increase integrin signaling/proliferation and activate cancer signaling pathways ERK, PFAK, and PI3K (9). Type I collagen has been implicated in increasing macrophage infiltration, and also inhibiting macrophages to polarize (9). Macrophages could polarize to an M1 activation state in the present study, despite the high expression of collagen, suggesting that the other proteins in the biochemically complex ECM are necessary for macrophage activation. Several ECM proteins related to gastrointestinal cancers and inflammation were identified as being increased in the neoplastic ECM including but not limited to COL8A1, lumican, and elastin.

COL8A1 is a non-fibrillar, short-chain collagen 60 kDa, that is pepsin-resistant. This collagen chain serves as a major component of the specialized ECM basement membranes; and is increased in tumorigenesis (50), including gastrointestinal cancers (51) and breast cancer (52). Lumican is a small, leucine rich proteoglycan 90 kDa that is upregulated with chronic inflammation (8) and GI cancers (53). Lumican is a core protein in the keratin sulfate proteoglycans (KSPG) family that can regulate collagen fibrillization; cell adhesion including epithelial cell migration and tissue repair; and importantly, macrophage attachment (53). Finally, elastin is important for the distensibility of the esophagus, with increased expression in the lower third of the esophagus (54); where EAC most frequently occurs (18). Elastin fragments recruit and elicit a TH1/M1 macrophage response (9, 14, 55), and many MMPs that are increased in EAC specifically target elastin (56). Positive feedback loops may be created wherein an inflammatory response is activated and elastin further degrades (14). Future work will determine the specific proteins or cleaved peptides with the potential to activate macrophage expression of TNFα+, either individually or synergistically.

4.3. Limitations, Future Directions, and Significance

There were limitations with the present study. Rat ECM was used for all experiments with the exception of the human ECM that was used for targeted and global proteomics. A bridging experiment was performed and showed that rat and human ECM both increase macrophage TNFα expression. ECM proteins are conserved across species (57–60), however the neoplastic signature identified in human (e.g., COL8A1, lumican, elastin) may be distinct from the rat neoplastic signature. The present study used solubilized ECM added to the media of macrophages cultured in 2D; therefore only the biochemical signals of the ECM on macrophages were investigated. The limitation of culturing cells on 2D tissue culture plastic is well understood (5, 61) and furthermore, does not evaluate ECM stiffness (8), density (8), geometries (7), and ECM fiber organization (8, 49) all of which may play a role in influencing cell behavior. These physical hydrogel properties likely have an effect on macrophage activation and epithelial cell migration, but were not evaluated in the present study. Finally, other important cell types in the EAC niche, including stem cells, fibroblasts, and other immune cells (neutrophils, dendritic cells, T cells, Tregs, and MDSCs), would likely be influenced by the normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM, but were not evaluated herein.

Despite the limitations, the distinctive effects of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM upon macrophage gene and protein expression, and the paracrine effect upon an esophageal epithelial cell are noteworthy. Even though ECM components are known to be central to inflammation and cancer progression (44), there is a need to isolate the biochemically complex ECM and determine ECM-cell interactions. Fractionating the ECM could further identify key ECM proteins in tumorigenesis as a reductionist approach. ECM hydrogels from decellularized cancer tissues can be prepared from diverse human cancer types and are compatible with 3D culture, tumor spheroids, and organ on a chip models (62).

There are several potential clinical applications of the present study findings. The results suggest TNFα can be a progressive biomarker for metaplastic and neoplastic disease; and showed increased concentration in patient-matched samples compared to media in the present study. Future work could determine the prevalence of COL8A1, lumican, and elastin in EAC biopsies as additional potential biomarkers. In addition, a current paradigm of cancer immunotherapy is the promotion of anti-tumor immunity by modulating macrophages from M2 to M1 (42). However, the results of the present study suggest it is important to understand macrophage activation in response to ECM, as neoplastic ECM promoted M1 pro-inflammatory TNFα activation. Perhaps a more effective, alternative therapeutic objective should be to modulate macrophage phenotype from “M(neoplastic ECM)” toward “M(normal ECM)” by providing normal ECM at the tumor niche. It was recently shown that “normal” esophageal extracellular matrix, of porcine origin, delivered orally in a dog model of Barrett’s esophagus reverted metaplastic epithelium to normal squamous epithelium in 4 of 6 animals and decreased TNFα+ expression compared to non-treated control (63). The results support the approach of providing normal ECM to re-educate the immune cell infiltrate. An additional alternative targeted approach could be to identify the macrophage receptor activated in response to the neoplastic or metaplastic ECM and intervene at the ECM-macrophage receptor site. The present study shows that while current chemotherapy targets the neoplastic cells, the neoplastic ECM remains a potent reservoir of signaling molecules from which to consider novel diagnostic or therapeutic approaches.

Supplementary Material

Fig S1. ECM hydrogel chromatographic profiles.

Fig S2. Pro-inflammatory (“M1-like”) and anti-inflammatory (“M2-like”) gene expression.

Fig S3. Endotoxin concentration of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM.

Fig S4. Immunolabeling of ECM treated macrophages with complete controls.

Table S1. Targeted proteomics of human normal and neoplastic tissue.

Table S2. Global proteomics of human normal and neoplastic tissue.

Highlights:

Normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic ECM were isolated from esophageal tissue

Neoplastic ECM had increased collagen alpha-1(VIII) chain, lumican, and elastin compared to normal ECM

Neoplastic ECM had a distinct effect upon macrophage signaling (promotes TNFα+)

Metaplastic and neoplastic ECM indirectly promote epithelial cell migration

Abnormal ECM can activate immune cells and affect normal cell function

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Dr. Neill Turner for helpful discussions and critical feedback of the manuscript, and the technical assistance of Lori Walton for histology. Funding for this work was provided by the NIH NIBIB under award number 2T32 EB001026–11 (LTS), NIH NCI under award number 1F31CA210694–01 (LTS), and the China Scholarship Council No. 201706940004 (XL).

Abbreviations:

- EAC

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophage

- UBM

Urinary bladder matrix

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest:

LTS, GH, and SFB hold officer positions and have a vested interest in ECM Therapeutics, Inc., which commercializes extracellular matrix materials and components. LH is currently employed by and owns stock in ACell, Inc., which commercializes urinary bladder matrix (UBM) as Gentrix™, MatriStem®, Cytal™, and MicroMatrix®. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sica A, Mantovani A, Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. The Journal of clinical investigation 122, 787–795 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena P, Sica A, Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends in immunology 23, 549–555 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M, The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends in immunology 25, 677–686 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P, Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. Journal of leukocyte biology 86, 1065–1073 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson CM, Bissell MJ, Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 22, 287–309 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay ED, Ed., Cell Biology of Extracellular Matrix, (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013), pp. 468. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z, Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 786–801 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox TR, Erler JT, Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer. Dis Model Mech 4, 165–178 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z, The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. The Journal of cell biology 196, 395–406 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z, Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3, (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM, Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 139, 891–906 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyce DE, Thomas A, Hart J, Moore K, Harding K, Hyaluronic acid induces tumour necrosis factor-alpha production by human macrophages in vitro. Br J Plast Surg 50, 362–368 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayahin JE, Buhrman JS, Zhang Y, Koh TJ, Gemeinhart RA, High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 1, 481–493 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adair-Kirk TL, Senior RM, Fragments of extracellular matrix as mediators of inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40, 1101–1110 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiodoni C, Colombo MP, Sangaletti S, Matricellular proteins: from homeostasis to inflammation, cancer, and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 29, 295–307 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huleihel L, Hussey GS, Naranjo JD, Zhang L, Dziki JL, Turner NJ, Stolz DB, Badylak SF, Matrix-bound nanovesicles within ECM bioscaffolds. Sci Adv 2, e1600502 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huleihel L, Bartolacci JG, Dziki JL, Vorobyov T, Arnold B, Scarritt ME, Pineda Molina C, LoPresti ST, Brown BN, Naranjo JD, Badylak SF, Matrix-Bound Nanovesicles Recapitulate Extracellular Matrix Effects on Macrophage Phenotype. Tissue engineering. Part A 23, 1283–1294 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pohl H, Welch HG, The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 97, 142–146 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saldin LT, Patel S, Zhang L, Huleihel L, Hussey GS, Nascari DG, Quijano LM, Li X, Raghu D, Bajwa AK, Smith NG, Chung CC, Omstead AN, Kosovec JE, Jobe BA, Turner NJ, Zaidi AH, Badylak SF, Extracellular matrix degradation products downregulate neoplastic esophageal cell phenotype. Tissue engineering. Part A, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Klug F, Prakash H, Huber PE, Seibel T, Bender N, Halama N, Pfirschke C, Voss RH, Timke C, Umansky L, Klapproth K, Schakel K, Garbi N, Jager D, Weitz J, Schmitz-Winnenthal H, Hammerling GJ, Beckhove P, Low-dose irradiation programs macrophage differentiation to an iNOS(+)/M1 phenotype that orchestrates effective T cell immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 24, 589–602 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allavena P, Mantovani A, Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: tumour-associated macrophages: undisputed stars of the inflammatory tumour microenvironment. Clin Exp Immunol 167, 195–205 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macke RA, Nason KS, Mukaisho K, Hattori T, Fujimura T, Sasaki S, Oyama K, Miyashita T, Ohta T, Miwa K, Gibson MK, Zaidi A, Malhotra U, Atasoy A, Foxwell T, Jobe B, Barrett’s esophagus and animal models. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1232, 392–400 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutherland RS, Baskin LS, Hayward SW, Cunha GR, Regeneration of bladder urothelium, smooth muscle, blood vessels and nerves into an acellular tissue matrix. J Urol 156, 571–577 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freytes DO, Martin J, Velankar SS, Lee AS, Badylak SF, Preparation and rheological characterization of a gel form of the porcine urinary bladder matrix. Biomaterials 29, 1630–1637 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crapo PM, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF, An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 32, 3233–3243 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf MT, Daly KA, Brennan-Pierce EP, Johnson SA, Carruthers CA, D’Amore A, Nagarkar SP, Velankar SS, Badylak SF, A hydrogel derived from decellularized dermal extracellular matrix. Biomaterials 33, 7028–7038 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calle EA, Hill RC, Leiby KL, Le AV, Gard AL, Madri JA, Hansen KC, Niklason LE, Targeted proteomics effectively quantifies differences between native lung and detergent-decellularized lung extracellular matrices. Acta biomaterialia 46, 91–100 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pratt JM, Simpson DM, Doherty MK, Rivers J, Gaskell SJ, Beynon RJ, Multiplexed absolute quantification for proteomics using concatenated signature peptides encoded by QconCAT genes. Nat Protoc 1, 1029–1043 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goddard ET, Hill RC, Barrett A, Betts C, Guo Q, Maller O, Borges VF, Hansen KC, Schedin P, Quantitative extracellular matrix proteomics to study mammary and liver tissue microenvironments. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 81, 223–232 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill RC, Calle EA, Dzieciatkowska M, Niklason LE, Hansen KC, Quantification of extracellular matrix proteins from a rat lung scaffold to provide a molecular readout for tissue engineering. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 14, 961–973 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slivka PF, Dearth CL, Keane TJ, Meng FW, Medberry CJ, Riggio RT, Reing JE, Badylak SF, Fractionation of an ECM hydrogel into structural and soluble components reveals distinctive roles in regulating macrophage behavior. Biomaterials Science 2, 1521 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huleihel L, Dziki JL, Bartolacci JG, Rausch T, Scarritt ME, Cramer MC, Vorobyov T, LoPresti ST, Swineheart IT, White LJ, Brown BN, Badylak SF, Macrophage phenotype in response to ECM bioscaffolds. Semin Immunol 29, 2–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chong J, Soufan O, Li C, Caraus I, Li S, Bourque G, Wishart DS, Xia J, MetaboAnalyst 4.0: towards more transparent and integrative metabolomics analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 46, W486–W494 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saldin LT, Cramer MC, Velankar SS, White LJ, Badylak SF, Extracellular matrix hydrogels from decellularized tissues: Structure and function. Acta biomaterialia 49, 1–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sicari BM, Dziki JL, Siu BF, Medberry CJ, Dearth CL, Badylak SF, The promotion of a constructive macrophage phenotype by solubilized extracellular matrix. Biomaterials 35, 8605–8612 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allavena P, Sica A, Solinas G, Porta C, Mantovani A, The inflammatory microenvironment in tumor progression: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 66, 1–9 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bissell MJ, Hall HG, Parry G, How does the extracellular matrix direct gene expression? J Theor Biol 99, 31–68 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani A, Sica A, Locati M, Macrophage polarization comes of age. Immunity 23, 344–346 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rieder F, Biancani P, Harnett K, Yerian L, Falk GW, Inflammatory mediators in gastroesophageal reflux disease: impact on esophageal motility, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 298, G571–581 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tselepis C, Perry I, Dawson C, Hardy R, Darnton SJ, McConkey C, Stuart RC, Wright N, Harrison R, Jankowski JA, Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in Barrett’s oesophagus: a potential novel mechanism of action. Oncogene 21, 6071–6081 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balkwill F, Mantovani A, Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357, 539–545 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F, Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI, STAT1 signaling regulates tumor-associated macrophage-mediated T cell deletion. J Immunol 174, 4880–4891 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mantovani A, Cancer: Inflaming metastasis. Nature 457, 36–37 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf MT, Ganguly S, Wang TL, Anderson CW, Sadtler K, Narain R, Cherry C, Parrillo AJ, Park BV, Wang G, Pan F, Sukumar S, Pardoll DM, Elisseeff JH, A biologic scaffold-associated type 2 immune microenvironment inhibits tumor formation and synergizes with checkpoint immunotherapy. Science translational medicine 11, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Badylak SF, Hoppo T, Nieponice A, Gilbert TW, Davison JM, Jobe BA, Esophageal preservation in five male patients after endoscopic inner-layer circumferential resection in the setting of superficial cancer: a regenerative medicine approach with a biologic scaffold. Tissue engineering. Part A 17, 1643–1650 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng FW, Slivka PF, Dearth CL, Badylak SF, Solubilized extracellular matrix from brain and urinary bladder elicits distinct functional and phenotypic responses in macrophages. Biomaterials 46, 131–140 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dziki JL, Wang DS, Pineda C, Sicari BM, Rausch T, Badylak SF, Solubilized extracellular matrix bioscaffolds derived from diverse source tissues differentially influence macrophage phenotype. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 105, 138–147 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Knittel JG, Yan L, Rueden CT, White JG, Keely PJ, Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. BMC Med 6, 11 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma ZH, Ma JH, Jia L, Zhao YF, Effect of enhanced expression of COL8A1 on lymphatic metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Exp Ther Med 4, 621–626 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vecchi M, Nuciforo P, Romagnoli S, Confalonieri S, Pellegrini C, Serio G, Quarto M, Capra M, Roviaro GC, Contessini Avesani E, Corsi C, Coggi G, Di Fiore PP, Bosari S, Gene expression analysis of early and advanced gastric cancers. Oncogene 26, 4284–4294 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giussani M, Merlino G, Cappelletti V, Tagliabue E, Daidone MG, Tumorextracellular matrix interactions: Identification of tools associated with breast cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol 35, 3–10 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seya T, Tanaka N, Shinji S, Yokoi K, Koizumi M, Teranishi N, Yamashita K, Tajiri T, Ishiwata T, Naito Z, Lumican expression in advanced colorectal cancer with nodal metastasis correlates with poor prognosis. Oncol Rep 16, 1225–1230 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venturi M, Bonavina L, Colombo L, Mussini E, Bauer D, and Peracchia A, in Recent Advances in Diseases of the Esophagus, Peracchia RRA, Bonavina L, Fumagalli U, Bona S, and Chella B, Ed. (Bologna, 1996), pp. 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houghton AM, Quintero PA, Perkins DL, Kobayashi DK, Kelley DG, Marconcini LA, Mecham RP, Senior RM, Shapiro SD, Elastin fragments drive disease progression in a murine model of emphysema. The Journal of clinical investigation 116, 753–759 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salmela MT, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Puolakkainen P, Saarialho-Kere U, Upregulation and differential expression of matrilysin (MMP-7) and metalloelastase (MMP-12) and their inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 in Barrett’s oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 85, 383–392 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernard MP, Chu ML, Myers JC, Ramirez F, Eikenberry EF, Prockop DJ, Nucleotide sequences of complementary deoxyribonucleic acids for the pro alpha 1 chain of human type I procollagen. Statistical evaluation of structures that are conserved during evolution. Biochemistry 22, 5213–5223 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bernard MP, Myers JC, Chu ML, Ramirez F, Eikenberry EF, Prockop DJ, Structure of a cDNA for the pro alpha 2 chain of human type I procollagen. Comparison with chick cDNA for pro alpha 2(I) identifies structurally conserved features of the protein and the gene. Biochemistry 22, 1139–1145 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Constantinou CD, Jimenez SA, Structure of cDNAs encoding the triple-helical domain of murine alpha 2 (VI) collagen chain and comparison to human and chick homologues. Use of polymerase chain reaction and partially degenerate oligonucleotide for generation of novel cDNA clones. Matrix 11, 1–9 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Exposito JY, D’Alessio M, Solursh M, Ramirez F, Sea urchin collagen evolutionarily homologous to vertebrate pro-alpha 2(I) collagen. The Journal of biological chemistry 267, 15559–15562 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson CM, Bissell MJ, Modeling dynamic reciprocity: Engineering three-dimensional culture models of breast architecture, function, and neoplastic transformation. Seminars in Cancer Biology 15, 342–352 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Villasante A, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Tissue-engineered models of human tumors for cancer research. Expert Opin Drug Discov 10, 257–268 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]