A new era of information technology (IT) has ushered in some unintended consequences and redefined what we know about improving patient safety.1 It is now clear we need approaches for not only using health IT to improve patient safety but also for ensuring the safety of the health IT equipment and software itself and to ensure that health IT is used completely (that is, by all clinicians to complete a specific task, such as ordering medications, laboratory tests and diagnostic imaging studies) and correctly to ensure patient safety.1 In March 2015, The Joint Commission released an updated Health IT Sentinel Alert, which took a broad, sociotechnical approach in exploring the factors involved in the safe use of health IT.2 Briefly, this alert suggested that health care organizations work on: (1) their safety culture by focusing on increasing their collective mindfulness with a goal of identifying, reporting, analyzing, and reducing health IT–related adverse events,; (2) implementing a “methodical approach to health IT process improvement” that includes proactively assessing patient safety risks; and (3) ensuring multidisciplinary leadership, support, and oversight of the planning, implementation and evaluation of health IT projects.

Multiple federal health IT efforts3 have emphasized safety as being key to the use of health IT within health care organizations (HCOs). During the last few years, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), along with many informatics researchers and professional organizations, has been working to enhance the safety and safe use of health IT from both the users’4 and developers’5,6 perspectives. What is needed now is a much more proactive approach on the part of the users—such as HCOs—to improving health IT–related safety, and that would entail the involvement of the HCOs’ patient safety professionals. Toward this end, in January 2014, ONC released the first version of the SAFER (Safety Assurance Factors for EHR Resilience) Guides. The nine SAFER Guides were designed to help health care organizations conduct self-assessments to optimize the safety and safe use of electronic health records (EHRs) in these areas: High Priority Practices, Organizational Responsibilities, Contingency Planning, System Configuration, System Interfaces, Patient Identification, Computerized Provider Order Entry with Decision Support, Test Results Reporting and Follow-Up, and Clinician Communication.7 The guides are used for proactive EHR risk assessment and suggest many practices, which we, along with another author, developed to improve the safety and safe use of EHRs.8 They provide tools and strategies that HCOs of all sizes, types, and specialties, as well as EHR developers, could use to proactively evaluate certain high-risk components (for example, computer-based provider order entry, test results review, system-to-system interfaces, system configuration) of their EHR-enabled clinical work systems,9 We recently updated these practices, and in November 2016, ONC posted updated versions of these recommended practices to stimulate their adoption across HCOs.10

A proactive assessment involves not only review of hardware, software, networking configurations, user actions and training but also work flows and organizational oversight of these activities. SAFER Guides take into account the fact that EHR–related safety risks arise not just from the features and functions of the technology itself, but also from the sociotechnical context and culture where these systems are implemented and used.7 For users interested in completing a proactive assessment, “fillable” copies of the SAFER Guides can be found at https://www.healthit.gov/safer/.11

In the three years after the SAFER Guides were first released, they were downloaded from the ONC website more than 52,000 times. In addition, some large HCOs have started to use them. For example, in July 2015 Bon Secours Health System (Ashland, Kentucky) convened a multidisciplinary group of clinicians and administrators to review the High Priority guide. 11

The group’s work led to Bon Secours Health System strengthening its IT infrastructure by increasing hardware redundancy and making improvements in several vulnerable clinical processes related to development and use of evidence-based order sets. In a survey conducted by Whitt et al., nursing students were asked to use SAFER Guides to assess the EHRs that they worked with during their training.12 Surprisingly, only 25% of the 159 respondents said their organization tested their computer-based provider order entry (CPOE) and clinical decision support (CDS) systems before go-live. Both the American Nursing Informatics Association13 and the American Medical Informatics Association14 have endorsed the SAFER Guides in recent policy statements. Although the concepts behind the SAFER guides are widely recognized as vitally important for safe and effective health IT implementation and use, current patient safety organizational activities do not necessarily facilitate or focus on assessment of health IT–related patient safety.

While the use of the SAFER Guides was expected to bolster patient safety in the EHR setting, few HCOs have used them for voluntary self-assessment to identify specific areas of vulnerability, and even fewer have created solutions and culture change to mitigate their EHR–related safety risks. Several reasons could be responsible, including competing priorities related to IT or patient safety, lack of methods or measurements to identify EHR safety issues as a top priority, lack of awareness about the guides, lack of resources or leadership support to either conduct the SAFER assessment or follow through on recommended practices, and lack of incentives or a “business case” to use the guides. In the sections below, we describe the updated SAFER Guides and provide guidance as to how HCOs and the risk management professionals that work within them can use the SAFER Guides and other health IT risk assessment tools as a part of their patient safety improvement programs.

Using the SAFER Guides

We provide the following recommendations, which are operationalized throughout this article, to help safety professionals as they embark on a proactive health IT assessment journey.

As we have argued, take a sociotechnical approach, which requires review of both technical (that is, hardware, software, and networking configurations) and “social” (that is, work flow, organizational culture, people, and policies) issues for assessment of health IT safety. Taking into consideration the full range of sociotechnical issues that affect patient safety within the complex EHR-enabled health care delivery system is essential for optimal results and consistent with other safety approaches.15

Make health IT–related patient safety a priority by refocusing the organization’s clinical governance structure to enable proactive risk assessment. For example, IT/informatics and patient safety/risk management departments should begin to work more closely together. Leadership engagement is critical. Ideally, the “C –suite”–level executives should be involved in bolstering EHR safety-related activities16 and regularly report EHR–related safety metrics to the organization’s governing board.17

Develop an environment that is conducive to detecting and learning from system vulnerabilities identified during SAFER assessments (for example, regularly review EHR system performance, usage, help-desk tickets, and error logs18). As more HCOs begin creating a “learning health care system,” it is critical that they include information collected about how the EHR itself is functioning and being used.19

The SAFER Guides can be a good start to implement these recommendations in an HCO, helping to position health IT safety at the center of its existing patient safety-oriented activities. They address the three domains of health IT–related patient safety,20 as follows; each domain is supported by one to three SAFER principles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Health Information Technology (IT) Safety Domains and the SAFER Principles Used to Develop the SAFER Guides

| Domain | SAFER Principles |

|---|---|

|

Domain 1 Safe Health IT: Address Safety Concerns Unique to Technology |

• Data

Availability–Health IT is accessible and usable upon

demand by authorized individuals. • Data Integrity – Health IT data or information is accurate and created appropriately and has not been altered or destroyed in an unauthorized manner. • Data Confidentiality – Health IT data or information is only available or disclosed to authorized persons or processes. |

|

Domain 2 Using Health IT Safely: Optimize the Safe Use of Technology |

• Complete/Correct Health IT

Use – Health IT features and functionality are

implemented and used as intended. • Health IT System Usability – Health IT features and functionality are designed and implemented so that they can be used effectively, efficiently, and to the satisfaction of the intended users to minimize the potential for harm. |

|

Domain 3 Monitoring Safety: Use Technology to Monitor and Improve Patient Safety |

• Surveillance and Optimization – As part of ongoing quality assurance and performance improvement, mechanisms are in place to monitor, detect, and report on the safety and safe use of health IT, and leverage health IT to reduce patient harm and improve safety. |

Safe Health IT, which pertains to addressing safety concerns that are unique and specific to technology, for example, making health IT hardware and software safe and free from defects and malfunctions).

Safe Use of Health IT, which includes safe, appropriate, and comprehensive use of technology by clinicians, staff, and patients, as well as identifying and mitigating unsafe changes in work flows that often emerge following the introduction and use of new technology.

Using Health IT to Improve Safety, which includes use of technology to identify and monitor patient safety events, risks, and hazards and to intervene before harm occurs. These domains account for the range of risks and opportunities for health IT to influence patient safety in both new and established health IT-enabled work systems.4

Recommended practices, 10 to 25 of which can be found in each SAFER Guide, are also organized according to the SAFER principles and can be assessed as “fully implemented,” “partially implemented,” or “not implemented.”

Recommended Practices

The SAFER recommended practices are intended to help the organization know “what” to do to optimize the safety and safe use of the EHR. They are listed in checklist-based format, along with an accompanying worksheet that provides more detail, and address why the recommended practices are needed. Any given recommended practice may relate to more than one of the six SAFER principles supporting health IT safety. The principles and practices were intended to be unambiguous activities and concepts that everyone, including users, HCOs and developers, would agree were the right things to do. SAFER Guides are further invigorated with real-world examples, which accompany each recommendation to help EHR users, HCOs, and developers better understand how they can meet each recommendation. Some examples might work better for some HCOs or users than others. Understanding and meeting SAFER recommendations requires people responsible for configuring and implementing the EHR, EHR users, and their EHR development partners to work together.

Overview of Updates to the SAFER Guides

The 2016 update to the guides reflects the rapidly accelerating pace of health IT applications and the resultant patient safety implications. It further takes into account comments from the EHR Association on the 2014 version,21 experience of those who used the guides,22 emerging risks, and new health IT–related safety research.23 The nine guides are still categorized into three broad groups, as follows, to address multiple EHR safety issues:8

Foundational Guides, which highlight several of the most important recommendations

Infrastructure Guides, which focus on the underlying hardware and software required by clinical applications

Clinical Process Guides, which draw attention to several mission-critical clinical processes

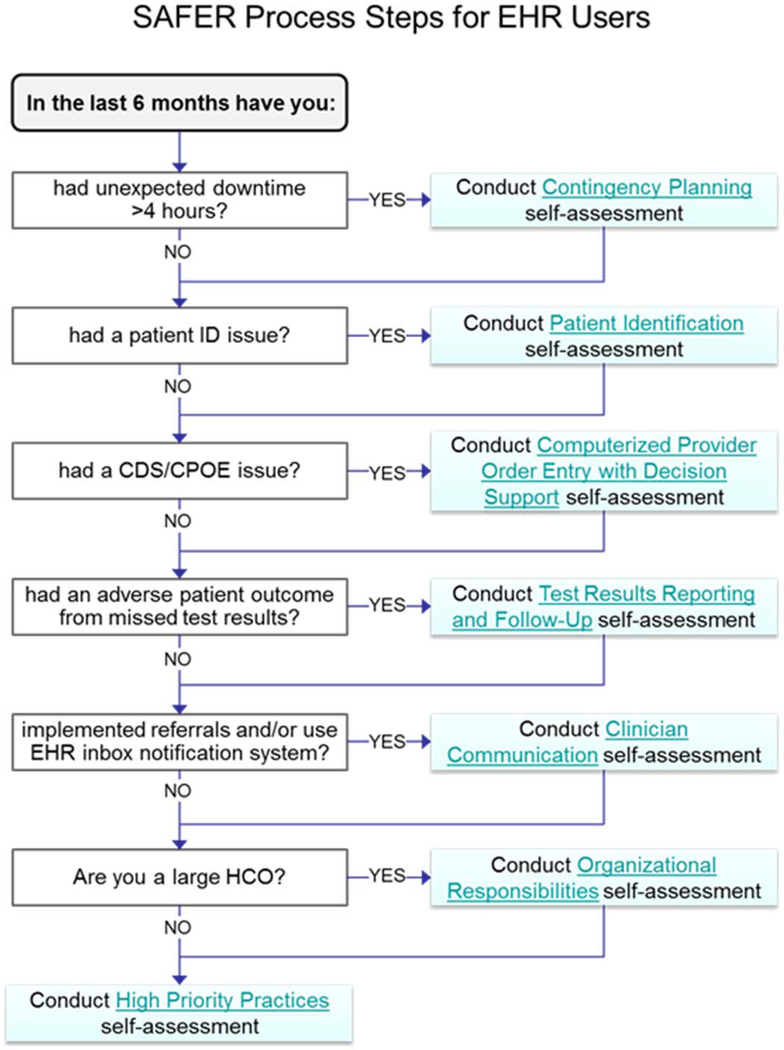

Because of the density of information in the nine guides, we recently developed a “Guide to the Guides” (see Figure 1) to help HCOs navigate them. To put these guides in recent real-world contexts, we now highlight some of the updates for each of the three guide categories.

Figure 1.

This flow chart is designed to guide health care organizations in using the SAFER Guide–facilitated proactive risk assessment.

Foundational Organizational Responsibilities Guide

In the Foundational Organizational Responsibilities Guide,24 we added three recommendations to help encourage HCOs to identify and address EHR safety concerns. The first of these recommendations states that HCOs should “develop a strategy for measurement of high-priority EHR safety hazards”—which builds directly on the 2016 National Quality Forum report Identification and Prioritization of HIT Patient Safety Measures”25 and is intended to advance our understanding of the full scope of EHR–related safety issues. The second recommendation states that “HCOs and their EHR developers must work together to identify and learn about EHR safety and thus share responsibility for improvement of existing EHRs.” The concept of shared responsibility was first introduced by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)26 in 2012, but in 2016 the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) added the concept as one of its key public policy principles.27 The third recommendation reiterates a long-standing Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)28 requirement that HCOs “train all EHR users and IT staff on best practices related to maintaining patient privacy and data confidentiality while working with protected health information (PHI).”

Clinical Process Guide for Test Results Reporting and Follow-up

In the Clinical Process Guide for Test Results Reporting and Follow-up,29 we added a recommendation aimed to reduce diagnostic errors that occur when the patient is not informed of abnormal diagnostic test results30. This recommendation builds on recommendations from the 2015 IOM report Improving Diagnosis in Health Care31 and promotes patient engagement as part of the diagnostic testing process32. Specifically, we recommend that “organizational policies and procedures ensure timely patient notification of both normal and abnormal test results and the timeliness of notification is monitored.”

Infrastructure Guide for Contingency Planning

Among the Infrastructure Guides, updates were made to the Contingency Planning Guide33 to reflect best practices for prevention and mitigation for the epidemic of “ransomware” attacks34 on hospitals around the world. Recent reports of poor user efficiency and type-ahead errors from “functional downtime” (that is, unacceptably slow EHR response time) led us to recommend “functional system downtimes [are] identified and addressed proactively.”

A Guide to Using the SAFER Guides

If the HCO uses remotely hosted or cloud-based EHR services that are preconfigured, its developer or hosting provider is responsible for ensuring that most of the recommendations are implemented correctly. Even in a remotely hosted setting, there are SAFER recommendations that are still the responsibility of the HCO. For example, as specified in the worksheet accompanying each recommendation, the HCO must ensure that it has a well thought-out paper-based system for documenting activities and ordering new medications, tests, and procedures when its EHR is unavailable because of problems in the remote data center or in its network connection. Conversely, if the HCO configures, implements, and maintains a locally hosted EHR, it should convene a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, health IT professionals, informaticians, risk managers, and administrators to review each of the SAFER recommendations. Depending on the HCO’s size and complexity, the number of people involved in reviewing the guides and their knowledge, and the depth of the discussion resulting from each recommendation, it could take anywhere from 30 minutes per guide to more than 20 minutes per recommendation.24 For example, during field testing of the Computerized Provider Order Entry with Decision Support Guide with nine chief medical information officers, each of whom individually filled out implementation status responses on behalf of their entire organization, the modal response time was less than 15 minutes (range, 5–30 minutes) for all 22 recommendations35. However, a multidisciplinary discussion for clarification or validation is often needed, which can take longer—and reviewing the guides is just the start of the EHR safety assessment. Changes required to “fully implement” a specific recommendation could be as “simple” as adjusting a specific EHR configuration parameter or involve more in-depth EHR modifications in combination with strengthening clinical work flows and related administrative processes and procedures. These latter processes can take several months.

One of the most frequent questions we receive is, “Where do we begin with the SAFER Guides?” We recommend that HCOs use Figure 1 to help prioritize their efforts. Then, when the multidisciplinary team is assembled, its members should ask themselves, “What types of health IT–related safety issues have we recently encountered?” Following the three-domain model for ensuring EHR safety,19 we recommend that the team begin by asking, “Is our system free from defects and malfunctions?” Table 2 illustrates several crucial questions that the organization could review and address to both mitigate (if there is a current problem) and prevent (if the potential for the problem exists) prolonged EHR downtime events.

Table 2.

Sample Questions and Recommendations to Help Health Care Organizations Get Started with the Contingency Planning SAFER Guide

| Mitigation / Prevention | Key Questions | SAFER Recommendation | Key Stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation | Are paper forms available to replace key EHR functions (e.g., enter orders and document medications administered) during downtimes? | There should be preprinted paper forms to care for patients on an in-patient unit for at least 8 hours. | Nursing and pharmacy staff |

| Mitigation | Is there a communication strategy that does not rely on the computing infrastructure (e.g., paging or cell phones) for downtime and recovery periods? | The organization has a mechanisms in place to activate the read-only backup EHR system and notify clinicians how to access it and to notify clinicians when the EHR is back on-line. | IT, Administration, nursing staff |

| Prevention | Is hardware that runs applications critical to the organization’s operation is duplicated? | Large HCOs that provide care 24 hrs/day have a remote “warm-site” (i.e., a site with current patient data that can be activated in less than 8 hrs and a redundant path to the Internet. | IT, Administration |

| Prevention | Is there is a comprehensive testing and monitoring strategy in place to prevent and manage EHR downtime events? | The HCO routinely monitors and reports on system downtime events and response time. | IT, Administration, Clinicians |

Next, the team could ask, “Have we experienced any patient identification problems?” Table 3 lists several sample questions that the organization could review and address as needed. Then the team could ask, “Have we had any computer-based order entry (CPOE)–related safety issues?”

Table 3.

Sample questions and recommendations to help HCOs get started with the Patient Identification SAFER guide.

| Mitigation / Prevention | Key questions | SAFER recommendation | Key stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation | Can HCO assign a “temporary” unique patient IDs in the event that the patient registration system is unavailable or the patient cannot provide the required information? | There is a process to assign temporary IDs to newborns and unresponsive patients arriving at the Emergency Department; staff are trained to merge temporary records into permanent ones. | Medical records, clinicians, administration, IT |

| Prevention | Are users warned when they attempt to create a record for a new patient (or look up a patient) whose first and last names are the same or similar to another patient, or attempt to look up a patient and the search returns multiple patients with the same or similar names? | During the creation of a new patient record, a phonetic algorithm, such as Soundex, is used to display an alert or warning if the patient, or a patient with similar demographic data, exists in the system. | IT, Registration clerks, Medical records |

| Prevention | Does the HCO regularly monitor its patient database for patient identification errors and potential duplicate patients or records? | The EHR has a mechanism to run a report listing potential duplicate patient records (e.g., multiple records for patients with the same first and last names); once identified duplicate records are reviewed and merged. | IT, Medical records |

Table 4 lists several sample questions that the HCO could review and address in this area. It is our hope that after HCOs begin to address these types of questions and recognize their potential risks that they will want to review additional guides.

Table 4.

Sample questions and recommendations to help HCOs get started with the Computer-based Order Entry with Clinical Decision Support SAFER guide.

| Mitigation / Prevention | Key questions | SAFER recommendation | Key stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation | Is critical patient information (e.g., age, weight, allergies, pregnancy status, creatinine clearance/GFR) visible during the order entry process? | Pertinent clinical information and identifying patient information is easily accessible from the ordering screen (e.g., in a patient header bar, on the ordering screen, from a hide/show panel). | Clinicians, pharmacy, laboratory, IT |

| Prevention | Are clinicians trained and tested on CPOE operations before being issued login credentials? | Clinicians are required to demonstrate basic CPOE skills before getting their login credentials and training is reinforced periodically, particularly with system changes and upgrades. | IT, Clinicians, Administration |

| Prevention | Are key safety-related metrics (e.g., override rates) defined, monitored, and acted on to optimize patient safety? | ■ Key CPOE and CDS safety indicators

are monitored and reported to leadership: ■ CPOE use rate ■ Frequency (i.e., volume) of orders that generate an alert ■ Override rate (i.e., % of alerts that are overridden) ■ Alerts with the highest % of overrides |

Clinicians, Administration, IT |

Patient safety professionals can use this methodology immediately to start implementing SAFER practices in their institutions. There might be some variation in the importance or urgency in implementing some of the recommended practices on the basis of the level of risk or type of practice setting. For example, a small, three-person primary care practice, unlike a large, multihospital integrated delivery system, would not need a large, interdisciplinary team to manage its clinical decision support content.36 If specific recommendations, such as inclusion of a patient photograph next to the patient’s name and other identifying information, cannot be met in the current iteration of the EHR software, the HCO should contact its EHR developer to help it develop a solution.

Operationalizing many of the SAFER recommendations, as specified along with each recommendation, often requires cooperation between those responsible for configuring and implementing the EHR and the EHR developers. Many recommendations may require adjusting specific EHR configuration parameters. HCOs should check with their EHR developer to see if they have created a manual for those responsible for configuring and implementing the system to help them learn how to meet or implement the recommendations. In every case, meeting SAFER recommendations requires that the people responsible for configuring and implementing the EHR, the EHR users and their EHR development partners work together.37

If the EHR developer provides a turnkey (that is, completely configured, ready-to-use solution, such as a remotely hosted or cloud-based EHR), it would have the added responsibility for ensuring that the majority of SAFER guide recommendations are met. Similarly, EHR developers supporting multiple health care delivery sites or operating in health care delivery systems requiring 24 hours/day × 365 days/year support have substantial responsibilities. Nevertheless, the scope of responsibilities for EHR developers providing stand-alone EHRs for small medical practices open only during usual working business hours might be less comprehensive than that of others.

Next Steps

On the basis of experience with the slow uptake and implementation of the recommendations following the release of the original SAFER Guides, as stated, new initiatives are needed to follow up on the release of the updated guides. In general, awareness of health IT–related safety risks within hospitals and ambulatory practices is quite limited.38 Three recent promising avenues can help create these new initiatives to stimulate wider adoption of SAFER Guides for safety improvement. First, ECRI’s nascent public-private “Partnership for Health IT Patient Safety”39 recently received funding of $3 million from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation in support of its multistakeholder collaborative to develop and promote mitigation strategies.40 As more stakeholders join this collaborative, it could be an ideal platform for uptake and dissemination of SAFER practices. Second, ONC has called for a National Health IT Safety Collaborative,41 which remains unfunded. Several of the SAFER Guides–related assessment activities could be promoted through this Collaborative. Third, The Pew Charitable Trusts and ONC cosponsored a “Health IT Safety Day” in December 2016, which was designed to create much needed momentum to help bolster policy initiatives related to the Safety Collaborative.42 While any of these national initiatives could help make SAFER Guides the centerpiece of a patient safety assessment and health IT improvement strategy, patient safety professionals in the meantime could be key champions in the local implementation of SAFER recommendations and should begin to use SAFER Guides to engage themselves in health IT–related activities.

New policy initiatives are also needed to provide incentives for HCOs and EHR developers to make these safety assessments. This might warrant the involvement of, say, The Joint Commission or the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to create an environment conducive to change. For example, we could imagine the Joint Commission including basic EHR–related safety issues during its on-site accreditation surveys.43 Furthermore, CMS could include proactive EHR safety assessments as one of its Conditions of Participation. The alignment of these agencies’ priorities and requirements regarding EHR–related safety could promote better accountability and shared responsibility among the different stakeholders involved in EHR safety.

In conclusion, we are optimistic that this commentary will provide a strong foundation for all HCOs to use proactive health IT risk assessment tools, such as the SAFER Guides, as a part of their patient safety improvement programs. Patient safety professionals could play key roles here, including championing the implementation of SAFER recommendations. New policy initiatives are also needed to incentivize health care organizations and EHR developers to make these safety assessments on a regular basis. Rigorously done proactive risk assessment that includes action on identified risk areas could have tangible effects in terms of the improvement of the safety and safe use of the EHR infrastructure in the United States.

Contributor Information

Dean F. Sittig, Professor of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas–Memorial Hermann Center for Healthcare Quality & Safety, School of Biomedical Informatics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Hardeep Singh, Chief, Health Policy, Quality and Informatics Program, United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston..

References

- 1.Sittig DF, Singh H. Electronic health records and national patient-safety goals. N Engl J Med. 2012. November 8;367(19):1854–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1205420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Joint Commission. Safe use of health information technology. Issue 54, March 31, 2015. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_54.pdf

- 3.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2016 Report To Congress on Health IT Progress: Examining the HITECH era and the future of health IT. November 2016. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/2016_report_to_congress_on_healthit_progress.pdf

- 4.Ratwani RM, Zachary Hettinger A, Kosydar A, Fairbanks RJ, Hodgkins ML. A framework for evaluating electronic health record vendor user-centered design and usability testing processes. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016. July 3. pii: ocw092. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sittig DF, Murphy DR, Smith MW, Russo E, Wright A, Singh H. Graphical display of diagnostic test results in electronic health records: a comparison of 8 systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. July;22(4):900–4. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McEvoy DS, Sittig DF, Hickman TT, Aaron S, Ai A, Amato M, Bauer DW, Fraser GM, Harper J, Kennemer A, Krall MA, Lehmann CU, Malhotra S, Murphy DR, O’Kelley B, Samal L, Schreiber R, Singh H, Thomas EJ, Vartian CV, Westmorland J, McCoy AB, Wright A. Variation in high-priority drug-drug interaction alerts across institutions and electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016. August 28. pii: ocw114. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sittig DF, Ash JS, Singh H. ONC issues guides for SAFER EHRs. J AHIMA. 2014. April;85(4):50–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sittig DF, Ash JS, Singh H. The SAFER guides: empowering organizations to improve the safety and effectiveness of electronic health records. Am J Manag Care. 2014. May;20(5):418–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh H, Ash JS, Sittig DF. Safety Assurance Factors for Electronic Health Record Resilience (SAFER): study protocol. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013. April 12;13:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. SAFER Guides, 2017. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/safer/

- 11.Sengstack P The Bon Secours Health System Convenes to Review the SAFER Guides. HISTalk Blog. July 29, 2015. Available at: http://histalk2.com/2015/07/29/readers-write-the-bon-secours-health-system-convenes-to-review-the-safer-guides/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitt KJ, Eden L, Merrill KC, Hughes M. Nursing Student Experiences Regarding Safe Use of Electronic Health Records: A Pilot Study of the Safety and Assurance Factors for EHR Resilience Guides. Comput Inform Nurs. 2016. August 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Nursing Informatics Association Position Statement. Addressing the Safety of Electronic Health Records. October 15, 2015. Available at: https://www.ania.org/assets/documents/PositionStatement_HITSafety.pdf

- 14.American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA). AMIA Public Policy Principles and Policy Positions. 2016. Available at: https://www.amia.org/sites/default/files/AMIA-2016-17-Policy-Priorities.pdf

- 15.Sittig DF, Singh H. A new sociotechnical model for studying health information technology in complex adaptive healthcare systems. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010. October;19 Suppl 3:i68–74. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menon S, Singh H, Giardina TD, Rayburn WL, Davis BP, Russo EM, Sittig DF. Safety huddles to proactively identify and address electronic health record safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017. March 1;24(2):261–267. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belmont E, Chao S, Chestler AL,Fox SJ, Lamar M, Rosati KB, Shay EF, Sittig DF, Valenti AJ. EHR-related Metrics to Promote Quality of Care and Patient Safety. Washington D.C.: American Health Lawyer’s Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright A, Hickman TT, McEvoy D, Aaron S, Ai A, Andersen JM, Hussain S, Ramoni R, Fiskio J, Sittig DF, Bates DW. Analysis of clinical decision support system malfunctions: a case series and survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016. November;23(6):1068–1076. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bindman AB. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Development of a Learning Health Care System. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. May 25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh H, Sittig DF. Measuring and improving patient safety through health information technology: The Health IT Safety Framework. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016. April;25(4):226–32. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.HIMSS Electronic Health Records Association. Comments on SAFER Guides. January 16, 2014. Available at: http://www.himssehra.org/docs/SAFER%20Guides%20Comments%20Final.pdf

- 22.Sengstack P The Bon Secours Health System Convenes to Review the SAFER Guides. HISTalk Blog. July 29, 2015. Available at: http://histalk2.com/2015/07/29/readers-write-the-bon-secours-health-system-convenes-to-review-the-safer-guides/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratwani R, Fairbanks T, Savage E, Adams K, Wittie M, Boone E, Hayden A, Barnes J, Hettinger Z, Gettinger A. Mind the Gap. A systematic review to identify usability and safety challenges and practices during electronic health record implementation. Appl Clin Inform. 2016. November 16;7(4):1069–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SAFER Organizational responsibilities guide. See: https://www.healthit.gov/safer/sites/safer/files/guides/safer_organizational_responsibilities.pdf

- 25.National Quality Forum. Identification and Prioritization of Health IT Patient Safety Measures. February 11, 2016. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=81710

- 26.Institute of Medicine. Health IT and Patient Safety: Building Safer Systems for Better Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p.111, 2012. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2011/Health-IT-and-Patient-Safety-Building-Safer-Systems-for-Better-Care.aspx [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA). AMIA Public Policy Principles and Policy Positions. 2016. Available at: https://www.amia.org/sites/default/files/AMIA-2016-17-Policy-Priorities.pdf

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Services. The HIPAA Privacy Rule. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/index.html

- 29.SAFER Test Results Reporting and Follow-up guide. See: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/safer_test_results_reporting.pdf

- 30.Singh H, Spitzmueller C, Petersen NJ, Sawhney MK, Smith MW, Murphy DR, Espadas D, Laxmisan A, Sittig DF. Primary care practitioners’ views on test result management in EHR-enabled health systems: a national survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013. July-August;20(4):727–35. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, Recommendation 7, 2015. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2015/improving-diagnosis-in-healthcare [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giardina T, Modi V, Parrish D, Singh H. The patient portal and abnormal test results: An exploratory study of patient experiences. Patient Experience Journal 2(1): 20; 2015. Available at: http://pxjournal.org/journal/vol2/iss1/20 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAFER Contingency Planning guide. See: https://www.healthit.gov/safer/sites/safer/files/guides/safer_contingency_planning.pdf

- 34.Sittig DF, Singh H. A Socio-Technical Approach to Preventing, Mitigating, and Recovering from Ransomware Attacks. Appl Clin Inform. 2016. June 29;7(2):624–32. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2016-04-SOA-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vartian CV, Singh H, Russo E, Sittig DF. Development and field testing of a self-assessment guide for computer-based provider order entry. J Healthc Manag. 2014. September-October;59(5):338–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright A, Sittig DF, Ash JS, Bates DW, Feblowitz J, Fraser G, Maviglia SM, McMullen C, Nichol WP, Pang JE, Starmer J, Middleton B. Governance for clinical decision support: case studies and recommended practices from leading institutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011. March-April;18(2):187–94. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2009.002030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sittig DF, Belmont E, Singh H. Improving the Safety of Health Information Technology Requires Shared Responsibility: It is Time We All Step Up. Healthcare: The Journal of Delivery Science and Innovation, 2017. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider EC, Ridgely MS, Meeker D, Hunter LE, Khodyakov D, Rudin RS. Promoting Patient Safety Through Effective Health Information Technology Risk Management. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2014. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR654.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ECRI Institute Partnership for Health IT Patient Safety. Available at: https://www.ecri.org/resource-center/Pages/HITPartnership.aspx

- 40.ECRI Institute. Grant Aims to Boost Health IT Safety Initiative. November 3, 2016. Available at: https://www.ecri.org/press/Pages/Grant-Aims-to-Boost-Health-IT-Safety-Initiative-.aspx

- 41.DeSalvo KB, Lewis L . Spotlighting Our Legislative Proposals to Better Foster the Flow of Health Information. Health IT Buzz. May 16, 2016. Available at: https://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/from-the-onc-desk/spotlighting-legislative-proposals-better-foster-flow-health-information/ [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pew Charitable Trust. Health IT Safety Day. December 6, 2016. Available at: https://www.cvent.com/c/express/44f6c6cf-0ee2-465f-9032-67e0283b4cf7

- 43.Sittig DF, Singh H. A red-flag-based approach to risk management of EHR-related safety concerns. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2013;33(2):21–6. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.21123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]