Abstract

Existing literature has demonstrated an association between higher adolescent religiousness and lower risk taking via higher self-regulation. The present study sought to elucidate the roles of emotion regulation and executive function as parallel mediators in the link between religiousness and risk taking in a sample of 167 adolescents (mean age = 14.13 years, 52% male, 82% White at Time 1). Longitudinal results across three waves utilizing structural equation modeling indicated higher religiousness was associated with higher emotion regulation, whereas religiousness was not associated with executive function. Subsequently, higher emotion regulation and executive function were associated with lower risk taking. Emotion regulation mediated the association between religiousness and risk taking. The findings highlight religiousness as a contextual protective factor for adolescents.

The developmental period of adolescence sees a marked increase in risk-taking behaviors. Recent literature has identified neurobiological underpinnings for the spike in risky behaviors in adolescence (e.g., Steinberg 2008, 2010) coupled with the more normative and adjustive nature of risk taking and antisocial behavior during adolescence (Moffitt, 1993). Resultantly, it is unsurprising to find a surge in risk-taking behaviors during this developmental period. The developmental cascades theory (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010) suggests that these risky behaviors may have a cascading effect on health and development, contributing to even more severe and cumulative consequences, such as the impairment of neural structures and their function (e.g., Goldstein & Volkow, 2002). However, clear individual differences emerge in adolescent risk taking such that some adolescents are more susceptible to risk taking than others. These individual differences provide a rich opportunity for researchers to identify pathways that contribute to or deter away from adolescent risk-taking behaviors.

Given such an opportunity, the present study sought to identify a pathway that deters risk taking in adolescence. As indicated by Steinberg (2014), adolescence is considered to begin earlier and end much later than previously thought, including more than just the teen years. Therefore, in our literature review, we identify the ages of 10-25 to be inclusive of adolescence. In the current longitudinal study, we used a sample of adolescents to investigate pathways involving religiousness to risk taking, mediated by emotion regulation and executive function, in order to elucidate the differential roles of these subdomains of self-regulation based on the theoretical background established in the existing literature. By understanding such pathways, the findings may provide critical information for targeted prevention and intervention efforts in this vulnerable segment of the population.

Religiousness and Risk Taking

We define religion as the search for significance in the ways that are related to the sacred (Pargament, 2007). The nature of religiousness is often represented as a multidimensional construct typically comprised of three distinct, yet strongly correlated, dimensions (Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016a), including organizational religiousness (e.g., religious service attendance), personal religiousness (e.g., importance of faith), and private practices (e.g., praying alone). Previous literature has provided some theoretical perspectives explaining the association of adolescent religiousness with risk-taking behaviors. For example, social control theory (Hirschi & Stark, 1969; Smith, 2003) proposed that religious communities provide more oversight of children as parents and adults within the community are familiar with each other and those who their children associate within the community. Moreover, religious communities create a more controlled environment for the child and allow him or her better access to positive adult role models of behavior, leading to a decrease in risky behaviors. In a similar way, divine interaction theory posits that believers may create a social relationship with a divine entity much in the same way as another human community member (Ellison, 1991). Rather than receiving guidance or oversight from other community members, the believer may instead seek out a divine entity for advice, comfort, meaning, and identity. Religiousness may also reduce risk taking by fostering self-regulation through the self-discipline required to engage regularly in a faith including attendance, reading of religious texts, and engaging in mindfulness rituals such as meditation and prayer (McCullough & Willoughby, 2009).

Vast amounts of studies have also empirically demonstrated the relation between religiousness and risk taking and other externalizing psychopathologies in adolescence (see King, Carr, & Boitor, 2011; Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016a for reviews). In particular, substance use has been negatively associated with religiousness across a robust range of studies. Furthermore, higher religiousness in adolescents has also been associated with lower risky sexual behaviors as well as lower delinquent, antisocial, and criminal behaviors. Taken together, there is clear evidence indicating religiousness is negatively associated with risk taking in adolescence.

The Mediating Role of Self-Regulation

Despite consistent findings associating higher adolescent religiousness with a broad range of risky behaviors, how religiousness operates to deter risk taking is not clearly understood. Recent literature has begun exploring a number of mediating factors that may play transactional roles in linking adolescent religiousness with risk taking (see Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016a for a review). As noted, one factor that has received increased attention both theoretically and empirically is self-regulation. McCullough and Willoughby (2009) proposed that religiousness may be associated with a variety of health, well-being, and social behaviors due to its influences on self-regulation. That is, religion functions to provide a critical avenue for self-regulatory development, including opportunities to engage in religious practices demanding of self-regulation such as prayer, attendance and participation at religious events, meditation, and fasting. As such, adolescent religiousness may influence risk-taking behaviors via self-regulation by providing an avenue for adolescents to develop self-regulatory abilities, which they may in turn employ to inhibit risky behaviors. Indeed, a range of empirical literature has corroborated this hypothesis (e.g., Desmond, Ulmer, & Bader, 2013; Kim-Spoon, Farley, Holmes, Longo, & McCullough, 2014; Vazsonyi & Jenkins, 2010).

Untangling the Roles of Emotion Regulation and Executive Function

Despite the growing evidence for the role of self-regulation linking religiousness and risk taking in adolescence, critical questions remain in elucidating the nature of this pathway. One line of research that is ripe for future investigations is increasing the specificity of the domains of self-regulation and the different roles they play in this mediating process. To date, research exploring religiousness, self-regulation, and risk taking has focused on examining either behavioral self-regulation (e.g., DeWall et al., 2014) or more global measures of self-regulation, typically including facets of emotion regulation and executive function mixed together interchangeably (e.g., Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016b; Raffaelli & Crockett, 2003). To date, it is unknown how the unique features of emotion regulation and executive function may play differential roles in the overarching relation among religiousness, self-regulation, and risk taking.

Presently, emotion regulation is conceptualized as the ability to modulate one’s emotional arousal in order to engage with the environment at an optimal level (Thompson, 1994). Such abilities underlie emotional self-awareness, socially appropriate emotional displays, and empathy/emotional understanding (e.g., Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Researchers from a cognitive neuroscience framework have described executive function as the “the ability to engage in deliberate, goal-directed thought and action via inhibitory control, attention shifting or cognitive flexibility, and working memory processes” (Liew, 2012, p. 106). In the current study, we consider self-regulation as emergent from emotion regulation and executive function with each making distinct contributions to the conceptualization of self-regulation. However, it is also important, given these distinct contributions, to examine when these unique aspects of self-regulation create differential relations with other constructs.

As such, when self-regulation is broken down into the subdomains of emotion regulation and executive function there is reason to believe that religiousness is most directly associated with emotion regulation, which carries the load in the well-demonstrated association between religiousness and self-regulation. Religiousness is thought to influence self-regulation via religious practices such as prayer, meditation, and fasting (McCullough & Willoughby, 2009). Such practices propagate the development of emotion regulation. Prayer is frequently used as a coping strategy for negative emotional states such as depression and anxiety (e.g., Koenig, George, & Siegler, 1988). Similarly, meditation is frequently employed to down regulate chaotic, stressful, panicked, or anxious emotions to more calming and serene emotional states (e.g., Oman, Shapiro, Thoresen, & Plante, 2008). Even religious fasting contributes to the development of emotion regulation given the need to resist the taxing emotional state induced by hunger (Fazel, 1998; Kadri et al., 2000). Furthermore, religious teachings and holy texts across almost all faith traditions frequently prescribe certain positive and health-promoting emotional states such as gratitude, compassion, love, and contrition while proscribing or alleviating negative and health-demoting emotional states such as jealousy, anger, fear, and lust (e.g., Ellison & Levin, 1998).

The attendance and participation requirements of religious services also provide ministers, peers, and other members to help one cope with stressful life experiences and develop emotion regulation skills with the aid of a supportive community (e.g., Graham & Haidt, 2010; McDougle, Konrath, Walk, & Handy, 2016). Furthermore, the highly meaningful personal relationship developed between the individual and the divine figure may act as a surrogate attachment figure or supportive entity to encourage emotion regulation development in a way similar to the function of human community members providing this support in organizational religiousness (Ellison, 1991). Taken together, it becomes evident that religiousness facilitates the development of emotion regulation.

Less can be said about the relation between religiousness and executive function, however. Limited empirical literature has addressed this association and the few available findings have been mixed. For example, (Inzlicht and colleagues 2009) reported that religious zeal was associated with indicators of executive function (i.e., Stroop accuracy and reaction time; Inzlicht, McGregor, Hirsh, & Nash, 2009). However, in their study of executive function and religiousness, Wain and Spinella (2007) reported significant correlations between religiousness and some of their executive function variables (i.e., motivational drive and empathy), but not others (i.e., impulse control, organization, and strategic planning). We note that the indicators of executive function significantly associated with religiousness in this previous study were largely different from the current conceptualization of executive function. As a result, the limited existing literature has not provided conclusive evidence of an association between religiousness and executive function.

Extant literature suggests pathways from emotion regulation and executive function to adolescent risk taking. Emotion regulation is likely to be important for deterring adolescent risk taking. Prior literature has indicated the link between emotion regulation and risk taking, including substance use and other risky behaviors (see Berking & Wupperman, 2012 for a review). For example, poor emotion regulation was associated with greater participation in risky behaviors including cigarette smoking and alcohol induced problem behaviors such as fighting and arguing in a sample of college students (Magar, Phillips, & Hosie, 2008). Similarly, poor emotion regulation was associated with higher substance use and good emotion regulation was associated with lower substance use in an adolescent sample (Wills, Walker, Mendoza, & Ainette, 2006). Additionally, evidence from neuroimaging literature suggests that dysregulation of the brain circuit underlying emotion regulation (i.e., orbital frontal cortex, amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, and other interconnected regions) may be a prelude to violence and aggression (Davidson, Putnam, & Larson, 2000).

For executive function, although Giancola and Mezzich (2003) theorized that poor executive function contributes to substance use, empirical findings have not been consistently supportive of the contribution of executive function to risk taking in adolescence. A prospective longitudinal study revealed that a composite measure of executive function did not predict later drug use among adolescent boys with and without a family history of substance use disorder (Giancola & Parker, 2001). Furthermore, another facet of executive function, higher working memory, was longitudinally associated with lower risk-taking behaviors indirectly via lower impulsivity in a sample of early adolescents; yet, executive function and risk taking were not directly related (Romer et al., 2011). Taken together, there is inconclusive evidence regarding the role of executive function in risk-taking behaviors, and whether this role functions above and beyond that of emotion regulation for adolescent risk taking.

The Present Study

The present longitudinal study sought to test emotion regulation and executive function as parallel mediators that link religiousness and risk taking over time. We hypothesized that higher religiousness at Time 1 would be associated with higher emotion regulation at Time 2 and sought to explore if there was an association between religiousness at Time 1 and executive function at Time 2. Second, we hypothesized that, in turn, higher emotion regulation at Time 2 would be associated with lower risk at Time 3 and, given the mixed findings in prior literature, we sought to explore whether executive function at Time 2 would be related to risk taking at Time 3. Finally, we hypothesized that emotion regulation at Time 2 would mediate the link between religiousness at Time 1 and risk taking at Time 3, and sought to explore whether a similar pattern existed for executive function at Time 2.

Method

Participants

Participants included 167 adolescents that took part in a longitudinal study on adolescent development. Participant demographic characteristics for each time point are presented in the online supplement. Characteristics for race/ethnicity, income, and religious affiliation were representative of the region in which the population was sampled (U.S. Census Bureau 2012).

Multinomial logistic regression was used to determine if the 33 adolescents who missed a wave of data collection were significantly different regarding Time 1 demographic variables from the 132 adolescents who participated at each wave. For individuals who did not participate at Time 1, demographic variables from Time 2 were utilized. Results indicated that participants who missed a time point were not significantly different than participants who did not miss a time point for any of the considered demographic variables (race: Wald test = 1.46, p = .23, sex: Wald test = .00, p = .97, age: Wald test = .60, p = .44, income: Wald test = 3.10, p = .08).

Procedures

Participants were recruited by diverse advertisement methods including flyers, recruitment letters, and e-mail distributions. Research assistants described the nature of the study to interested individuals over the telephone and invited them to participate. Data collection took place at the university offices where adolescents and their primary caregivers were interviewed separately by trained research assistants and received monetary compensation for their participation in the study. All adolescent participants provided written assent and their parents provided consent for a protocol approved by the university’s institutional review board, and they received monetary compensation for participation at each time point, with slight increases in the payment amount for each yearly follow-up.

Measures

Religiousness.

Adolescents’ religiousness was measured at Time 1 as an average of self-reports on three subscales of religiousness, including organizational religiousness, personal religiousness, and private practices; all the items were adapted from previously published measures: the Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/ Spirituality (Fetzer & NIA, 1999) and Jessor’s Value on Religion Scale (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Organizational religiousness (two items) focused on formal religious participation and attendance. A typical item was “How often do you go to religious services?” and the items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = More than once a week” to “6 = Never.” Personal religiousness (four items) focused on the importance of religion in one’s life. A typical item was “How important is religious faith in your life?” The items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = Very important” to “5 = Not at all important.” Finally, private practices (four items) focused on informal religious participation alone or with few other individuals. A typical item was “How often do you pray privately in places other than at church or synagogue?” and the items were rated on an 8-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = More than once a day” to “8 = Never.” All responses were scored so that higher scores indicated higher religiousness. Alphas for all three subscales were greater than .83.

Emotion Regulation.

Emotion regulation was measured at Time 2 via self-reports on eight items from the emotion regulation subscale of the Emotion Regulation Checklist (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). The purpose of this measure is to identify emotional processes that are important for adaptive regulation of the self, including socially appropriate emotional displays, empathy, and emotional self-awareness. A typical item was, “I can say when I am feeling sad, angry or mad, fearful or afraid,” and potential answers ranged from “1 = rarely/never” to “4 = always.” All responses were scored so that higher scores indicated higher emotion regulation. In the current sample, the alpha was .57 at Time 2.

Executive function.

Executive function was a factor score derived from a latent variable at Time 2 comprised of three behavioral indicators of working memory, updating/set shifting, and inhibitory control. These indicators have been previously identified as core indicators of executive function (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to confirm factor structure (all p’s < .01) and generate the factor score for subsequent analyses to preserve power. The CFA was a fully saturated model and, thus, did not have fit indices. First, working memory was assessed via the Stanford-Binet Digit Span Task (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986). Second, updating/set shifting was assessed via the Wisconsin Card Sort Task (WCST; Heaton & P.A.R. Staff, 2003). Participants were required to identify the rule to properly sort the card (based on shape, color, or quantity) and successfully update and shift to the new sorting rules when they occur. Higher scores were indicative of higher updating/set shifting. Third, inhibitory control was measured via the Multiple Source Interference Task (MSIT; Bush, Shin, Holmes, Rosen, & Vogt, 2003). The MSIT requires participants to indicate which of three numbers is different from the other two. In neutral conditions, target numbers were congruent with the numbers’ presented locations. In interference conditions, target numbers were incongruent with the target locations (e.g., 2 was in the third position). Following (MacDonald and colleagues 2012), we used intraindividual variability in reaction time which was indexed as intraindividual standard deviations (ISDs) across correct response latency trials of interference conditions.

Risk Taking.

Adolescent risk taking was measured at Time 3 via self-reports on 19 items from an adaption of Things I Do (Conger & Elder, 1994), which has been used previously in adolescent samples (Kim-Spoon, Holmes, & Deater-Deckard, 2015). The measure focused on identifying frequency of adolescent risk-taking behaviors varying in severity over the past year. For example, typical items included “Ridden in a car without a seatbelt,” and “Drunk a bottle or glass of beer or other alcohol.” The answer format was “0 = Not at all,” “1 = once or twice,” or “2 = more than twice.” All items were scored so that higher scores indicated higher risk taking. In the current sample, the alpha was .84 at Time 3.

Plan of Analysis

For all study variables, descriptive statistics were examined to determine normality of distributions and multivariate outliers were identified via Mahalanobis Distance. Furthermore, general linear modeling (GLM) was used to identify significant multivariate predictors of the endogenous variables among the Time 1 demographic variables of age, sex, race, and total family income. Any Time 1 demographic variables that were significant (p < .05) were used as covariates. The hypothesized models were tested via Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) using MPlus statistical software version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). To test significance levels of mediated effects, bias corrected bootstrap estimations of the 95% confidence interval were used (i.e., Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedures were used for missing data (Arbuckle, 1996). Finally, we utilized nested models and the Wald Test of χ2 differences to determine if there were significant differences between the paths of religiousness at Time 1 to emotion regulation at Time 2 and religiousness at Time 1 to executive function at Time 2. Further, we tested for significant differences between the paths of emotion regulation at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3 and executive function at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for study variables may be found in Table 1. Data revealed all study variables were normally distributed and two multivariate outliers. We compared models that included or excluded these cases and found significant differences in path coefficients; thus, the cases were excluded from the main analyses. The GLM revealed that Time 1 demographic variables were not significantly associated with the endogenous variables (family income: Wilks’ Lambda = .68, p = .12, race: Wilks’ Lambda = .99, p = .64, age: Wilks’ Lambda = .96, p = .21, sex: Wilks’ Lambda = .95, p = .11); therefore, no demographic variables were included in the subsequent models as covariates.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Religiousness Time 1 | 5.59 (1.99) | |||||||||

| 2 | Organizational religiousness Time 1 | .90** | 5.57 (2.07) | ||||||||

| 3 | Personal religiousness Time 1 | .92** | .72** | 6.63 (2.33) | |||||||

| 4 | Private practices Time 1 | .93** | .78** | .79** | 4.57 (2.10) | ||||||

| 5 | Emotion regulation Time 2 | .22** | .11 | .24** | .25** | 3.10 (.41) | |||||

| 6 | Executive function Time 2 | .02 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .34** | .00 (.02) | ||||

| 7 | Shifting Time 2 | −.10 | −.07 | −.12 | −.08 | .17* | .57** | .00 (1.00) | |||

| 8 | Working memory Time 2 | .03 | .02 | .06 | .02 | .17* | .46** | .10 | .00 (1.00) | ||

| 9 | Inhibitory control Time 2 | .06 | .03 | .08 | .04 | .31** | .91** | .27** | .22** | .00 (1.00) | |

| 10 | Risk taking Time 3 | −.05 | −.02 | −.09 | −.03 | −.25** | −.19* | −.13 | −.08 | −.16 | 1.32 (.27) |

p < .05,

p < .01

Hypothesis Testing

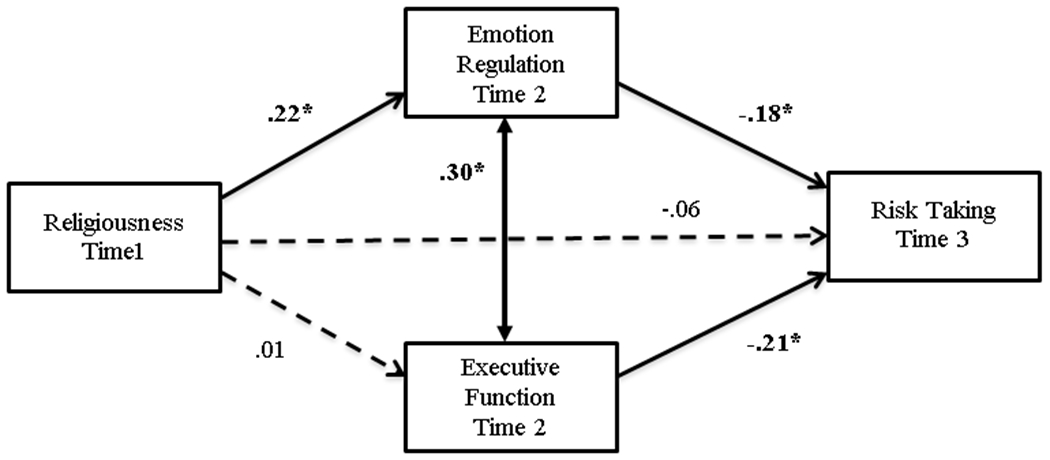

The model estimated all possible pathways among study variables, thus this model was fully saturated (χ2 = 0.00, df = 0.00). As seen in Figure 1, the results indicated that higher religiousness at Time 1 was associated with higher emotion regulation at Time 2 (b = .05, SE = .02, p = .01). In turn, higher emotion regulation at Time 2 was associated with lower risk taking at Time 3 (b = −.11, SE = .05, p = .04). Religiousness at Time 1 was not associated with executive function at Time 2 (b = .00, SE = .00, p = .88). However, higher executive function at Time 2 was associated with lower risk taking at Time 3 (b = −2.14, SE = .94, p = .02). Religiousness at Time 1 was not associated with risk taking at Time 3 (b = −.01, SE = .01, p = .47). Additionally, executive function at Time 2 and emotion regulation at Time 2 covaried significantly (r = .30, p < .001). Finally, the bias corrected bootstrapping test of the indirect effects indicated that emotion regulation at Time 2 mediated the link between religiousness at Time 1 and risk taking at Time 3 (beta = −.04, 95% CI: [−.11, −.01]), but executive function at Time 2 did not (beta = .00, 95% CI: [−.05, .04]).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model results of religiousness, emotion regulation, executive function, and risk taking.

Note: Standardized estimates are presented (see text for unstandardized results). Bold face indicates significant coefficients.

* p < .05.

Next, we utilized nested model testing to determine if the association of religiousness at Time 1 with emotion regulation at Time 2 was significantly stronger compared to the corresponding association of religiousness at Time 1 with executive function at Time 2. We tested if the model fit significantly degraded by imposing equality constraints between the path from religiousness at Time 1 to emotion regulation at Time 2 and the path from religiousness at Time 1 to executive function at Time 2. The result indeed indicated that the path from religiousness at Time 1 to emotion regulation at Time 2 was significantly stronger than the path from religiousness at Time 1 to executive function at Time 2 (Wald test = 7.69, df = 1, p < .01). Additionally, we tested if the association from emotion regulation at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3 was significantly different from the corresponding association from executive function at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3. Data indicated the path from executive function at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3 was significantly stronger than the path from emotion regulation at Time 2 to risk taking at Time 3 (Wald test = 5.81, df = 1, p = .02).

Discussion

The current longitudinal study sought to untangle the relations among religiousness, dimensions of self-regulation, and risk taking in adolescents. Specifically, the present study tested a model of parallel mediation with emotion regulation and executive function as mediators in the association between religiousness and risk taking. Investigations such as these are particularly important to address given the need of exploring factors contributing to individual differences in self-regulation development for targeted prevention and intervention strategies of adolescent health risk behaviors. In particular, more proximal influences of risk taking, such as emotion regulation and executive function may be considered as potential targets of intervention for deterring risk taking in adolescence.

First, we hypothesized that religiousness was more predominantly associated with emotion regulation relative to executive function. The results supported this hypothesis. Indeed, higher religiousness at Time 1 was associated with higher emotion regulation at Time 2, but was not significantly associated with executive function at Time 2. Further, the test of parameter constraints indicated the path from religiousness at Time 1 to emotion regulation at Time 2 was significantly stronger than the path from religiousness at Time 1 to executive function at Time 2. The finding that religiousness was associated more strongly with emotion regulation than executive function provides discriminant validity for the separation of these constructs, although they are related constructs under the broader umbrella of self-regulation and significantly correlated with each other. The current conceptualization of emotion regulation—as underlying emotional self-awareness, socially appropriate emotional displays, and empathy/emotional understanding (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997)—clearly distinguishes itself from executive function in relation to religiousness. The present study provides empirical evidence that the emotion regulation and executive function differentially in the pathway from adolescent religiousness to risk taking and are thus best understood when considered individually rather than in unison. This finding also has implications for future studies, highlighting the importance of clarifying the domains of self-regulation that may be most relevant to the study constructs (e.g., Nigg, 2016).

Our findings based on longitudinal data uniquely demonstrated the aspect of self-regulation religiousness promotes, namely emotion regulation. Although this finding has not been previously demonstrated directly, to the authors’ knowledge, many studies have provided indirect empirical and theoretical support of it (e.g., Ellison, 1991; Graham & Haidt, 2010; Kadri et al., 2000; Koenig et al., 1988; McDougle et al., 2016; Oman et al., 2008). In light of this, our findings suggest religiousness as a critical factor for emotion regulation development. By encouraging adolescents with existing religious beliefs to participate fully in their faith, clinicians may be able to help bolster emotion regulation in adolescents with deficits in these skills. Similarly, adolescents without religious beliefs may still benefit from the knowledge and skill gained by this pathway, as the clinician may encourage emotional self-awareness, empathy, and socially appropriate emotional displays through quiet reflection, meditation, or participation in organized communities that do not necessarily have a religious affiliation.

Second, we hypothesized that, in turn, higher emotion regulation at Time 2 would be associated with lower risk at Time 3. In contrast, given the mixed findings in prior literature, we sought to explore whether executive function at Time 2 would be related to risk taking at Time 3. The present study is the first to consider emotion regulation and executive function simultaneously in predicting adolescent risk taking, allowing an investigation of the effects of each above and beyond the other. The data supported the hypothesis, showing that better emotion regulation was associated with less risk taking. This finding corroborates previous studies demonstrating the importance of emotion regulation for preventing risk-taking behaviors (e.g., Davidson et al., 2000; Magar et al., 2008; Wills et al., 2006). Additionally, our data showed a significant association between executive function and risk taking, and further revealed that this association was significantly stronger than the association between emotion regulation and risk taking. This finding of the significant link between executive function and risk taking helps address the lack of evidence in previous literature regarding the role of executive function in adolescent risk-taking behaviors. Whereas prior literature has found an indirect effect from executive function to risk taking (e.g., Romer et al., 2009), the current study found a direct association, and this association existed above and beyond the effects of emotion regulation. This finding may be a result of differences in the operationalization of executive function. However, the present study demonstrates greater predictive validity of the executive function composite constructed based on theoretical dimensions of executive function proposed by Miyake and colleagues (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). Although additional studies may help further solidify the evidence for the executive function-risk taking association, our findings provide preliminary evidence that executive function explains individual differences in adolescent risk-taking behaviors, above and beyond emotion regulation. An implication of this finding is that clinicians attempting to reduce risk-taking behaviors may target executive function, as well as emotion regulation.

Finally, we hypothesized that emotion regulation at Time 2 would mediate the relation between religiousness at Time 1 and risk taking at Time 3, and explore if the same pattern existed for executive function at Time 2. This hypothesis was supported as higher religiousness was associated with lower risk taking via higher emotion regulation. However, executive function did not mediate the link between religiousness and risk taking. The finding regarding emotion regulation is analogous to a range of studies that have found self-regulation to be a mediator between religiousness and adolescent risk taking (see Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016a for a review). Importantly, by simultaneously considering the two primary dimensions of self-regulation as parallel mediators, the present study sheds light on the specific pathway through which religiousness contributes to demoting adolescent risk taking. It follows that religiousness may be considered a contextual factor with protective effects for adolescent risk taking and, as noted, existing religiousness may be utilized by the clinicians in an effort to intervene or prevent risk-taking behaviors, or practices akin to those in organized religion may be encouraged without necessarily including religious connotations.

Limitations and Conclusion

The findings must be interpreted in light of the limitations of the current study. First, although the study as a whole uses multiple methods (self-report and behavioral tasks), within each construct only one method was used (i.e., only behavioral tasks for executive function and only self-reports for the others). Thus, the finding regarding the significant associations of emotion regulation with religiousness and risk taking, may be, in part, influenced by the common-method variance (i.e., sharing the same questionnaire method). However, the behavioral tasks that were incorporated into the present study formed a latent construct that was moderately correlated with self-reported emotion regulation (demonstrating convergent validity) as well as self-reported risk taking (demonstrating predictive validity). Future studies may benefit from using multiple methods within each construct. Second, because these are correlational analyses, directions of the effects could not be strictly tested. However, the present study was grounded in prior theoretical and empirical work as well as demonstrating temporal precedence across three waves which helps mitigate this limitation. Third, the relatively low Cronbach alpha of the Emotion Regulation Checklist is a limitation. However, low alphas tend to underestimate effects, thus effects found in the current study could have been stronger, not weaker, if the scores had demonstrated higher reliability (e.g., Furr & Bacharach, 2008). Finally, the lack of direct association between religiousness at Time 1 and risk taking at Time 3 is surprising, given the prior finding of modest, yet robust association between religiousness and externalizing behaviors (e.g., Holmes & Kim-Spoon, 2016a for a review). In this community sample of early to middle adolescents, risk-taking behavior prevalence was relatively low, resulting in limited variance, which may have contributed to the dampened longitudinal effect of religiousness.

Despite these limitations, the present study makes important, unique contributions to the existing literature on protective mechanisms of adolescent risk taking. For one, the current findings may advance the field by showing that religiousness specifically facilitates emotion regulation, rather than executive function, enhancing our understanding of why religiousness is associated with risk taking. Secondly, emotion regulation and executive function were simultaneously considered in predicting risk-taking behaviors and it was found that both higher emotion regulation and higher executive function were associated with lower risk taking. This finding helps to clarify a mixed literature that has struggled to find a direct association between executive function and risk-taking behaviors. Finally, the current study corroborated previous studies that found significant mediating effects from religiousness to risk taking through self-regulation in adolescence. However, the current study did so with an imperative clarification of only emotion regulation functioning in this way, and not executive function. This is an important distinction to consider when characterizing the role religiousness may play in deterring adolescent risk taking. Taken together, the findings provide critical information for the targeted prevention and intervention efforts for adolescent risk taking by offering insight into factors—i.e., most proximally emotion regulation and executive function, but also religiousness contextually—which may deter this significant public health issue and further reduce potentially cascading lifelong difficulties such as addiction or incarceration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA036017 awarded to Jungmeen Kim-Spoon and Brooks King-Casas and DA027827 awarded to Gene Brody). We thank Jacob Elder, Katherine Faris, Julee Farley, Toria Herd, Anna Hochgraf, Kristin Peviani, and Jeannette Walters for help with data collection. We are grateful to adolescents and parents who participated in our study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Arbuckle JL (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In Marcoulides GA & Schumacker RE (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, & Wupperman P (2012). Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models, (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Shin LM, Holmes J, Rosen BR, & Vogt BA (2003). The Multi-Source Interference Task: Validation study with fMRI in individual subjects. Molecular Psychiatry, 8, 60–70. DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Elder GH (1994). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural American. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, & Larson CL (2000). Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation--a possible prelude to violence. Science, 289, 591–594. DOI: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond SA, Ulmer JT, & Bader CD (2013). Religion, self-control, and substance use. Deviant Behavior, 34, 384–406. DOI: 10.1080/01639625.2012.726170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Pond RS Jr, Carter EC, McCullough ME, Lambert NM, Fincham FD, & Nezlek JB (2014). Explaining the relationship between religiousness and substance use: Self-control matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107, 339–351. DOI: 10.1037/a0036853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 32, 80–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2136801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Levin JS (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 25, 700–720. DOI: 10.1177/109019819802500603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M (1998). Medical implications of controlled fasting. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 91, 260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute & National Institute on Aging Working Group (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo, MI: Fetzer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Furr RM, & Bacharach VR (2008). Psychometrics: An introduction. Sage Publications, California. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, & Mezzich AC (2003). Executive functioning, temperament, and drug use involvement in adolescent females with a substance use disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 857–866. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, & Parker AM (2001). A six-year prospective study of pathways toward drug use in adolescent boys with and without a family history of a substance use disorder. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 62, 166–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, & Volkow ND (2002). Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. American Journal of Psychiatry,159, 1642–1652. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, & Haidt J (2010). Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 140–150. DOI: 10.1177/1088868309353415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, & Staff PAR (2003). Wisconsin card sorting test: Computer version 4-research edition (WCST: CV4). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, & Stark R (1969). Hellfire and delinquency. Social Problems, 17, 202–213. DOI: 10.2307/799866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, & Kim-Spoon J (2016a). Why are religiousness and spirituality associated with externalizing psychopathology? A literature review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19, 1–20. DOI: 10.1007/s10567-015-0199-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, & Kim-Spoon J (2016b). Positive and negative associations between adolescents’ religiousness and health behaviors via self-regulation. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 6, 188–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, McGregor I, Hirsh JB, & Nash K (2009). Neural markers of religious conviction. Psychological Science, 20, 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, & Jessor SL (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kadri N, Tilane A, El Batal M, Taltit Y, Tahiri SM, & Moussaoui D (2000). Irritability during the month of Ramadan. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Farley JP, Holmes CJ, Longo GS, & McCullough ME (2014). Processes linking parents’ and adolescents’ religiousness and adolescent substance use: Monitoring and self-control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 745–756. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-013-9998-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Spoon J, Holmes C, & Deater-Deckard K (2015). Attention regulates anger and fear to predict changes in adolescent risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 756–765. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, Carr D, & Boitor C (2011). Religion, spirituality, positive youth development, and thriving. In Lerner RM, Lerner JV & Benson JB (Eds.), Advances in Child Development and Behavior (Vol. 41, pp. 164–197). London, England: Academic. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, & Siegler IC (1988). The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. The Gerontologist, 28(3), 303–310. DOI: 10.1093/geront/28.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Marks LD, & Marrero MD (2011). Religiosity, self-control, and antisocial behavior: Religiosity as a promotive and protective factor. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32, 78–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liew J (2012). Effortful control, executive functions, and education: Bringing self-regulatory and social-emotional competencies to the table. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 105–111. DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00196.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD (2013). Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SWS, Karlsson S, Rieckmann A, Nyberg L, & Bäckman L (2012). Aging-related increases in behavioral variability: Relations to losses in dopamine D1 receptors. Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 8186–8191. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5474-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magar EC, Phillips LH, & Hosie JA (2008). Self-regulation and risk-taking. Personality and Individual Differences, 45, 153–159. DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Cicchetti D (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 491–495. DOI: 10.1017/S0954579410000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, & Willoughby BL (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 69–93. DOI: 10.1037/a0014213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle L, Konrath S, Walk M, & Handy F (2016). Religious and secular coping strategies and mortality risk among older adults. Social Indicators Research, 125(2), 677–694. DOI: 10.1007/s11205-014-0852-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, & Friedman NP (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 8–14. DOI: 10.1177/0963721411429458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701. DOI: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT (2016). Annual research review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 361–383. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Shapiro SL, Thoresen CE, Plante TG, & Flinders T (2008). Meditation lowers stress and supports forgiveness among college students: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 56, 569–578. DOI: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.569-578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI (2007). Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York, NY: Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. DOI: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, & Crockett LJ (2003). Sexual risk taking in adolescence: the role of self-regulation and attraction to risk. Developmental Psychology, 39, 1036–1046. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM, Yang W, & Hurt H (2011). Does adolescent risk taking imply weak executive function? A prospective study of relations between working memory performance, impulsivity, and risk taking in early adolescence. Developmental Science,14, 1119–1133. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01061.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, & Cicchetti D (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906–916. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C (2003). Theorizing religious effects among American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 17–30. DOI: 10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28, 78–106. DOI: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2010). A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Psychobiology, 52, 216–224. DOI: 10.1002/dev.20445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of a definition. In Fox NA (Ed.), The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike RL, Hagen EP, & Sattler JM (1986). The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Fourth Edition Guide for Administering and Scoring. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2012). American Community Survey. Retrieved April 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vazsonyi AT, & Jenkins DD (2010). Religiosity, self-control, and virginity status in college students from the “Bible Belt”: a research note. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49, 561–568. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wain O, & Spinella M (2007). Executive functions in morality, religion, and paranormal beliefs. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117, 135–146. DOI: 10.1080/00207450500534068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Mendoza D, & Ainette MG (2006). Behavioral and emotional self-control: relations to substance use in samples of middle and high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 265–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.