Abstract

Bodyweight training (BWT) is a style of interval exercise based on classic principles of physical education. Limited research, however, has examined the efficacy of BWT on cardiorespiratory fitness. This is especially true for simple BWT protocols that do not require extraordinarily high levels of effort. We examined the effect of a BWT protocol, modelled after the original “Five Basic Exercises” (5BX) plan, on peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) in healthy, inactive adults (20 ± 1 y; body mass index: 20 ± 5 kg/m2; mean ± SD). Participants were randomized to a training group that performed 18 sessions over six weeks (n=9), or a non-training control group (n = 10). The 11-minute session involved five exercises (burpees, high knees, split squat jumps, high knees, squat jumps), each performed for 60-seconds at a self-selected “challenging” pace, interspersed with active recovery periods (walking). Mean intensity during training was 82 ± 5% of maximal heart rate, rating of perceived exertion was 14 ± 3 out of 20, and compliance was 100%. ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between groups after the intervention, such that VO2peak was higher in the training group compared to control (34.2 ± 6.4 vs 30.3 ± 11.1 ml/kg/min; p = 0.03). Peak power output during the VO2peak test was also higher after training compared to control (211 ± 43 vs 191 ±50 W, p = 0.004). There were no changes in leg muscular endurance, handgrip strength or vertical jump height in either group. We conclude that simple BWT— requiring minimal time commitment and no specialized equipment — can enhance cardiorespiratory fitness in inactive adults. These findings have relevance for individuals seeking practical, time-efficient approaches to exercise.

Keywords: Interval exercise, peak oxygen uptake, physical conditioning

INTRODUCTION

Physical inactivity remains prevalent despite strong evidence that cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is independently associated with mortality and disease risk (14). Common cited barriers to regular physical activity include a perceived lack of time, and access to appropriate equipment and facilities (28). The latter has been exacerbated by public health measures and behavioural changes in response to the novel coronavirus, and the challenge of maintaining metabolic health during a global pandemic (13). There is value in identifying simple, time-efficient exercise strategies that increase CRF — as objectively measured by peak oxygen uptake (V̇O2peak) — given that even a modest improvement in this parameter is associated with a reduction in mortality risk (7).

Vigorous intermittent exercise, including protocols broadly characterized as high intensity interval training (HIIT), can enhance markers of cardiometabolic health despite relatively low time commitment (2). Practical and feasible applications of HIIT include brief, vigorous intermittent stair climbing, which as has been shown to increase CRF without the need for specialized equipment (1, 9). Bodyweight training (BWT) is another popular variant of HIIT adopted by many practitioners (26), but limited research has examined the efficacy of simple BWT on CRF (8, 15, 22, 23). This is particularly true for submaximal protocols that do not require extraordinarily high levels of effort.

5BX — “Five Basic Exercises” — was a fitness plan developed over a half century ago by the Royal Canadian Air Force based on classic principles of physical education (21). It was initially intended for service members stationed in remote outposts, but has enduring relevance as a simple, practical approach to conditioning. The original 5BX plan required only 11 minutes per day, was not dependent on elaborate facilities or equipment, and could be appropriately scaled based on fitness level. Performing the 5BX plan for several months has been reported to improve submaximal indices of CRF and exercise tolerance (10), including in individuals with cardiovascular disease (19). The original 5BX plan included stretching, which places minimal stress on the cardiovascular system, and exercises such as sit-ups that are generally not recommended today.

The present study examined the effect of a contemporary BWT program on CRF in healthy, inactive adults. The intervention was modelled on the original 5BX plan, but modified to include calisthenics and bodyweight movements that are now commonly recommended for this style of training (12, 27). Brief bouts of vigorous exercise were interspersed with recovery periods, and the program required eleven minutes per session. We hypothesized that VO2peak following the BWT intervention, which consisted of 18 sessions over six weeks, would be higher compared to a non-training control group.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-two individuals were recruited from the McMaster University community. Participants were deemed healthy, based on completion of the Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology (CSEP) Get Active Questionnaire (GAQ) (4). Participants were inactive, based on self-report of accumulating < 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous weekly activity. Exclusion criteria included the diagnosis of a cardiometabolic disease or musculoskeletal condition that would contraindicate BWT. Participants were randomized in a counterbalanced manner to a training group or a non-training control group. The control group was invited to complete the training intervention after study completion. A sample size of 10 participants per group was estimated to detect a 1-metabolic equivalent (MET) difference in our primary outcome, VO2peak, based on means and standard deviations from previous studies in our lab, at an alpha level of 0.05 with 80% power. Three individuals withdrew for reasons unrelated to the study, leaving n = 9 individuals who completed the intervention (five males and four females; 20 ± 1 years, body mass index = 21 ± 5 kg/m2, mean ± SD) and n = 10 in the control group (one male and nine females, 19 ± 0 years, 21 ± 5 kg/m2). The experimental procedures were approved by the McMaster Research Ethics Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. This research was carried out fully in accordance to the ethical standards of the International Journal of Exercise Science (18).

Protocol

Participants initially performed an incremental ramp test to exhaustion using an electronically-braked cycle ergometer (Excalibur Sport V 2.0, Lode, Groningen, The Netherlands) and metabolic cart (Quark CPET, COSMED, Chicago, IL, USA) to determine V̇O2peak and peak power (Wpeak) as previously described (1,9). Participants subsequently returned to the laboratory to become familiarized with muscular fitness testing, and baseline testing was completed ~24–72 hours later. After a 2-minute walking warm-up, peak leg power was determined based on the best of three maximal jumps performed from a semi-squat position, and hand grip strength was determined using a dynamometer (Smedley Hand Dynamometer, Stoelting Co, Wood Dale, IL, USA), as detailed elsewhere (3). Muscular endurance was assessed using a wall sit test to volitional fatigue, involving an isometric squat with the knees flexed at 90 degrees, as confirmed by a goniometer (Baseline Plastic Goniometer 12–1000, Fabrication Enterprises, White Plains, NY).

Participants were randomized with a 1:1 allocation ratio using a concealed envelope after baseline testing. The training group returned to the lab to become familiarized with the nature of the exercises to be performed, and the 6 – 20 Borg rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale. Training commenced 72 hours after the familiarization visit, and a total of three sessions were performed each week for six weeks. Each training session consisted of an 11-minute protocol that involved alternating bouts of vigorous exercise and light active recovery, in addition to a brief warm-up and cool-down. The specific protocol and order of exercises was:

Warm-up: 1-minute of jumping jacks;

Vigorous exercise: 1-minute of modified burpees without push-ups;

Recovery: 1-minute of walking in place;

Vigorous exercise: 1-minute of high knee running in place;

Recovery: 1-minute of walking in place;

Vigorous exercise: 1-minute of split squat jumps;

Recovery: 1-minute of walking in place;

Vigorous exercise: 1-minute of high knee running in place;

Recovery: 1-minute of walking in place;

Vigorous exercise: 1-minute of squat jumps;

Cool-down: 1-minute of walking in place.

For each bout of vigorous exercise, participants self-selected a relative intensity (i.e. effort level) based on instructions to choose a “challenging pace”, with the goal of completing as many repetitions as possible. All sessions were supervised by one of the investigators, but no additional direction or encouragement was provided. Heart rate (HR) was monitored continuously for subsequent analysis (Polar A300, Kempele, Finland) and RPE was recorded after each exercise bout. All participants completed all training sessions. Enjoyment was assessed using the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (11) immediately following the first and last training session. The post-training V̇O2peak test was conducted ~72 hours after the final training session, or 6 weeks after baseline testing in the control group, followed ~24 – 72 hours later by muscular fitness testing.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 10 for control, n = 9 for training). V̇O2peak, Wpeak, peak leg power, wall sit time, and grip strength data were analysed with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), using baseline values as the covariate on IBM SPSS (IBM Corp., Version 25.0, Armonk, NY, USA) as previously described (9). This approach tests whether groups are different on the post-test while controlling for pre-test values (20). Cohen’s d was used to determine effect size from baseline to post testing within the training group. Enjoyment during the first and final sessions was compared with a two-tailed paired t-test. Significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

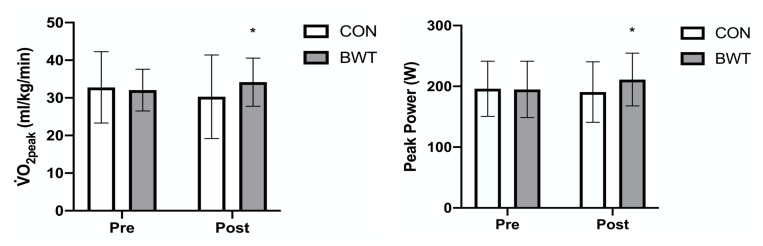

ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between groups after the intervention, such that V̇O2peak was higher in the training group compared to control (34.2 ± 6.4 vs 30.3 ± 11.1 ml/kg/min, p = 0.03, d = 0.38) (Figure 1). The mean increase from baseline in the intervention group was ~7% (2.1 ± 4.5 ml/kg/min), which corresponded to ~0.5 MET. Wpeak was also higher after training compared to control (211 ± 43 vs 191 ± 50 W, p = 0.004, d = 0.35) (Figure 1). Grip strength, peak leg power, and wall sit time were not different between groups after the intervention. Mean exercise HR, averaged over all training sessions, was 82 ± 5% of maximum (165 ± 10 bpm) and RPE was 14 ± 3. Enjoyment ratings tended to increase but were not different between the first and last session (98 ± 14 vs 86 ± 12; p = 0.06).

Figure 1.

V̇O2peak (left panel) and peak power (right panel) measured before (Pre) and after (Post) six weeks of bodyweight training (BWT) or an equivalent period without a prescribed exercise intervention (CON). Values are means ± SD. *p < 0.05 between groups.

DISCUSSION

The major novel finding of the present study was that VO2peak was higher following a simple BWT program, as compared to a non-training control group, in previously inactive young adults. The 11-minute protocol was modelled on classic principles of physical education and the original 5BX plan. It involved basic exercises performed at a self-selected “challenging” pace, interspersed with active recovery periods, and was performed thrice weekly for six weeks.

HIIT has re-emerged in recent years as one of the most popular fitness trends worldwide, with “Tabata”-style training being one particularly well-known variant (26). This method is commonly practiced using bodyweight intervals that resemble traditional calisthenics, although the original study involved cycling bouts at a workload equivalent to ~170% of VO2max (25). This specific protocol involves eight 20-second cycles of ‘all out’ effort interspersed with 10-seconds of rest, and requires an extraordinarily high level of motivation. BWT applied using a Tabata-style approach can increase CRF (15, 22), although there are equivocal data in this regard (8). The very intense nature of the efforts required, however, makes this type of training unsuited or unpalatable for some individuals. Other studies have demonstrated the potential for less intensive BWT —typically performed in conjunction with equipment-based exercises — to increase CRF (17), including in people at risk for cardiometabolic diseases (5).

The protocol in the present study did not precisely mimic the classic 5BX plan, but modelled some essential aspects: it involved basic exercises and only eleven minutes per session, was not dependent on elaborate facilities or equipment, and was scaled to individual fitness by having participants self-select their effort (i.e., a “challenging pace”). Despite the relatively training low time commitment, the protocol enhanced exercise tolerance, as evidenced by a higher V̇O2peak and Wpeak following the intervention, as compared to a non-training control group (Figure 1). The change in V̇O2peak in the BWT group was less than the ~1 MET improvement reported in previous 6-week training studies that employed brief, intermittent exercise interventions including vigorous stairclimbing (1) and stationary cycling (6, 16). Nonetheless, even a modest improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with a reduction in mortality risk and small changes may confer benefits to cardiometabolic health (7).

Considerable attention has recently been focused on the psychological responses to interval exercise. The emerging data support the viability of this type of activity as an alternative to traditional, moderate-intensity continuous exercise (24). High adherence to free-living HIIT in previously sedentary overweight and obese adults has been observed in conjunction with high levels of enjoyment (29). In the present study, enjoyment remained high at the end of the 6-week training period and not different compared to the start of the program. These data suggest that at least short-term BWT performed at a self-selected pace could be a sustainable exercise strategy in previously inactive individuals, but adherence to self-paced BWT warrants further study.

There are several limitations to the present work. The sample size was relatively small, and while participants were deemed inactive based on self-report of not meeting weekly physical activity guidelines, this varied between individuals. Diet and physical activity — aside from the prescribed exercise — was not specifically controlled or monitored over the course of the study, for example, through the use of food parcels or activity trackers. While this simulated “free living” conditions, potential changes in these factors may have contributed to measurement variability, or introduced confounding influences beyond the training intervention. Larger, longer and more sophisticated studies are warranted to more comprehensively assess the effect of simple BWT on health-related responses, as well as the underlying physiological mechanisms, and behavioural implications. A recent study compared twelve weeks of virtually-monitored, home-based BWT to moderate-intensity continuous training and a lab-based HIIT intervention. It did not include a non-exercise control group, but found the three protocols similarly increased CRF, whole-body insulin sensitivity, and skeletal muscle capillarization and mitochondrial density (23).

In summary, the present results suggest that CRF can be enhanced through simple bodyweight training that is modelled on classic principles of physical education, and the original 5BX plan. The 11-minute protocol employed in this study involved basic exercises performed at a self-selected “challenging” pace, and required no specialized equipment. These findings have relevance for individuals seeking practical, time-efficient approaches to exercise, a quest that is particularly challenging during a global pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported with funds from McMaster University and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) to MJG. LRA held a NSERC Undergraduate Student Research Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison MK, Baglole JH, Martin BJ, MacInnis MJ, Gurd BJ, Gibala MJ. Brief intense stair climbing improves cardiorespiratory fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(2):298–307. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batacan RB, Jr, Duncan MJ, Dalbo VJ, Tucker PS, Fenning AS. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(6):494–503. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CSEP. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology - Physical Activity Training for Health (CSEP-PATH) Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; Ottawa, ON, Canada: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CSEP. Get Active Questionnaire. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; Ottawa, ON, Canada: 2017. Available from http://www.csep.ca/home. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fealy CE, Niewoudt S, Foucher JA, Scelsi AR, Malin SK, Pagadala M, Cruz LA, Li M, Rocco M, Burguera B, Kirwan JP. Functional high intensity exercise training ameliorates insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk factors in type 2 diabetes. Exp Physiol. 2018;103(7):85–994. doi: 10.1113/EP086844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillen JB, Percival ME, Skelly LE, Martin BJ, Tan RB, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. Three minutes of all-out intermittent exercise per week increases skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and improves cardiometabolic health. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imboden MT, Harber MP, Whaley MH, Finch WH, Bishop DL, Fleenor BS, Kaminsky LA. The association between the change in directly measured cardiorespiratory fitness across time and mortality risk. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2019;62(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam H, Siemens TL, Matusiak JBL, Sawula L, Bonafiglia JT, Preobrazenski N, Jung ME, Gurd BJ. Cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular endurance responses immediately and 2 months after a whole-body Tabata or vigorous-intensity continuous training intervention. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45(6):650–658. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2019-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins EM, Nairn LN, Skelly LE, Little JP, Gibala MJ. Do stair climbing exercise “snacks” improve cardiorespiratory fitness? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019;44(6):681–684. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2018-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappagoda CT, Linden RJ, Newell JP. Effect of the Canadian Air Force training programme on a submaximal exercise test. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1979;64(3):185–204. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1979.sp002472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendzierski D, DeCarlo KJ. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1991;13(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilka B, Jordan C. High-intensity circuit training using body weight: Maximum results with minimal investment. ACSM’s Health Fit J. 2013;17(3):8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.King AJ, Burke LM, Halson SL, Hawley JA. The challenge of maintaining metabolic health during a global pandemic. Sports Med. 2020;50(7):1233–1241. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Shimano H, Ohashi Y, Yamada N, Sone H. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2009;301(19):2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McRae G, Payne A, Zelt JGE, Scribbans TD, Jung ME, Little JP, Gurd BJ. Extremely low volume, whole-body aerobic–resistance training improves aerobic fitness and muscular endurance in females. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37(6):1124–1131. doi: 10.1139/h2012-093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metcalfe RS, Babraj JA, Fawkner SG, Vollaard NB. Towards the minimal amount of exercise for improving metabolic health: Beneficial effects of reduced-exertion high-intensity interval training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(7):2767–75. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2254-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers TR, Schneider MG, Schmale MS, Hazell TJ. Whole-body aerobic resistance training circuit improves aerobic fitness and muscle strength in sedentary young females. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(6):1592–1600. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navalta JW, Stone WJ, Lyons TS. Ethical issues relating to scientific discovery in exercise science. Int J Exerc Sci. 2019;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.70252/EYCD6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffo JA, Luksic IY, Kappagoda CT, Mary DA, Whitaker W, Linden RJ. Effects of physical training on myocardial ischaemia in patients with coronary artery disease. Br Heart J. 1980;43(3):262–269. doi: 10.1136/hrt.43.3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rausch JR, Maxwell SE, Kelley K. Analytic methods for questions pertaining to a randomized pretest, post-test, follow-up design. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:467–486. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royal Canadian Air Force Exercise Plans for Physical Fitness. 1962. Available from: https://archive.org/details/Royl_Canadian_Air_Force_Exercise_Plans_.

- 22.Schaun GZ, Pinto SS, Silva MR, Dolinski DB, Alberton CL. Whole-body high-intensity interval training induces similar cardiorespiratory adaptations compared with traditional high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in healthy men. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(10):2730–2742. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott SN, Shepherd SO, Hopkins N, Dawson EA, Strauss JA, Wright DJ, Cooper RG, Kumar P, Wagenmakers AJM, Cocks M. Home-hit improves muscle capillarisation and eNOS/NAD(P)H oxidase protein ratio in obese individuals with elevated cardiovascular disease risk. J Physiol. 2019;597(16):4203–4225. doi: 10.1113/JP278062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stork MJ, Banfield LE, Gibala MJ, Martin Ginis KA. A scoping review of the psychological responses to interval exercise: Is interval exercise a viable alternative to traditional exercise? Health Psychol Rev. 2017;11:324–344. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2017.1326011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tabata I, Nishimura K, Kouzaki M, Hirai Y, Ogita F, Miyachi M, Yamamoto K. Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO2max. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28(10):1327–1330. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199610000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson WR. Worldwide survey of fitness trends for 2020. ACSM’s Health Fit J. 2019;23(6):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Scientific 7-Minute Workout. 2013. https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/09/the-scientific-7-minute-workout/

- 28.Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vella CA, Taylor K, Drummer D. High-intensity interval and moderate-intensity continuous training elicit similar enjoyment and adherence levels in overweight and obese adults. Eur J Sport Sci. 2017;17(9):1203–1211. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2017.1359679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]