Although the informed involvement of patients in shared decision-making is commonly acknowledged to be an ideal situation, this is rarely achieved,1 leading to important adverse consequences.2 It can be a communication challenge for clinicians to involve patients in informed and shared decision-making (ISDM). We defined the “competencies” needed for ISDM3 in order to address this problem systematically through medical education. These competencies are communication skills related to building of partnerships; eliciting of preferences for receiving information and playing a role in decision-making; exploring of ideas, concerns and expectations; presenting of choices and evidence; reaching a decision and resolving conflict; and agreeing on an action plan and follow-up.

In this study, we asked, What are the most frequent and challenging situations that require ISDM skills experienced by family practice preceptors of medical students? The information could be used to refine training in communication skills, because students and preceptors are likely to be motivated to learn approaches to difficult and common problems.

It has been reported that the “difficult patient” occurs in 10%–20% of primary care encounters,4 but the terms used in the substantial “difficult patient” literature do not seem to be congruent with the “difficulties” that physicians may have in engaging patients in ISDM. Some examples that do seem relevant have been suggested by Platt and Gordon:5 “nonadherence,” “the list maker,” “the patient's companion,” “the patient bearing literature” and, in a survey of general practitioners' frequent problems, “patient's noncompliance with treatment and follow-up,” “sharing understanding of the problem with the patient” and “differences in expectations between physician and patient.”6

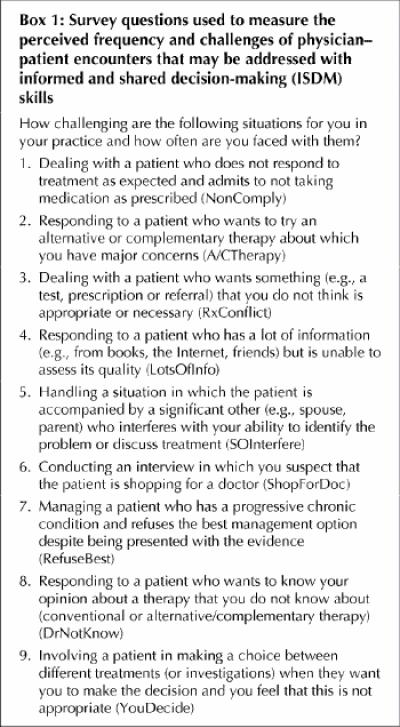

We wrote survey questions to portray generic situations in physician–patient encounters that pose a challenge to ISDM. The scenarios were developed and refined by stepwise and iterative consultation with physicians who had wide experience in teaching and examining communication skills and had helped to define the competencies for ISDM. The survey form was constructed with the attention to detail and format suggested by Woodward.7 Problems were expressed as 9 items, for example, “dealing with a patient who does not respond to treatment as expected and admits to not taking medication as prescribed” (Box 1). Respondents were asked to what degree they felt challenged by the problem and how frequently they encountered it on 5-point scales from “1: not challenging (you feel effective and easily able to address the problem and it causes you little anxiety)” to “3: moderately challenging” to “5: very challenging (you find this to be quite a difficult problem and anxiety provoking)” and from “1: once a year” to “3: once a month” to “5: most days.” An illustrative example (dealing with a patient who is “drug-seeking”) was used at the beginning of the questionnaire as an anchor for the scale.

Box 1.

The survey was mailed to all 285 family practice preceptors of medical students at the University of British Columbia. The survey was anonymous. Guidelines for maximizing returns were followed.8 The response rate was 88% and the survey showed high internal consistency, with a Cronbach α of 0.82 for challenge and 0.84 for frequency. Of the physicians who completed the survey, 51% were local and 49% were rural; 66% were in group practices, 26% in solo practices, 1% in walk-in clinics and 7% indicated “other”; and 74% were male. The average time in practice was 14 years, with a range from 0.5 to 42 years.

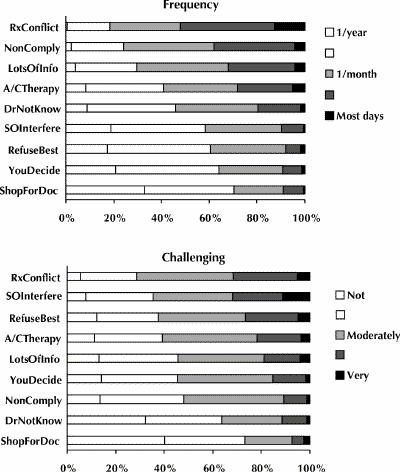

The most challenging problems were conflict resolution, dealing with “significant others” and patients' refusal of best treatment. The most frequent problems were conflict resolution, noncompliance and patients with lots of information (Fig. 1). There were no important correlations with physicians' type of practice, sex or years of experience.

Fig. 1: Percentage of responses from family practice preceptors for level of frequency (top) and challenge (bottom) for each item in the questionnaire. For expansions of abbreviations, see Box 1.

Our results indicate that training in communication skills for undergraduates should include attention to conflict resolution and negotiation skills and that their preceptors also need help with this. Training should also provide students with strategies for managing decision-making in the context of patients and their companions.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements: We are especially indebted to the physicians who helped us create and carry out the survey: Drs. Stephen Barron, Betty Calam, Stefan Grzybowski, Jacqueline Hurst, Joy Masuhara, Katherine McManus, James Salzman, Robert Voigt, Arthur van Wart, Robert Woollard (Department of Family Practice) and Andrew Chalmers (Department of Medicine).

The protocol was approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board. This work was supported by a grant from The Max Bell Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. William Godolphin, Rm. G227, 2211 Wesbrook Mall, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC V6T 2B5; fax 604 822-7635; wgod@unixg.ubc.ca

References

- 1.Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice. Time to get back to basics. JAMA 1999;282:2313-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Barber N, Bradley CP. Misunderstandings in prescribing decisions in general practice: qualitative study. BMJ 2000; 320:484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision making. BMJ 1999;319:766-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Brody D, Williams JBW, Linzer M, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Platt FW, Gordon GH. Field guide to the difficult patient interview. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

- 6.Leclère H, Beaulieu MD, Bordage G, Sindon A, Couillard M. Why are clinical problems difficult? General practitioners' opinions concerning 24 clinical problems. CMAJ 1990;143(12):1305-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Woodward CA. Questionnaire construction and question writing for research in medical education. Med Educ 1988;22:347-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1978.